INSIDE: Ouray Ice Park

The Dark Side to Safety Culture

The Mountain Keeps the Story

Our Mountain Home: 100 Years of Mazama Lodges

Rab Athlete Felipe Tapia Nordenflycht and Erik Weihenmayer climb on the La Aleta del Tiburon (Shark’s Fin) in the first light of day. With a 3 am start, they aim for Erik to be the first blind person to summit various towers in the Torres del Paine. But summiting proves to be the easy part. Nordenflycht says, “The real crux is navigating the approach and descent.”

2 MAZAMAS

WWW.RAB.EQUIPMENT

MAZAMA BULLETIN

Volume 105

Number 3

May/June 2023

IN THIS ISSUE CONTENTS

FEATURES

It's Time to Climb!, p. 8

Ouray Ice Park, p. 9

The Dark Side to Safety Culture, p. 14

Learning to Climb!, p. 18

The Mountain Keeps the Story, p. 19

Various Climbs in the Ragged Range, p. 24

2023 Steep Snow and Ice Skill-Builder Set for August, p. 27

A Roundabout Journey to the Emblem Peaks, p. 29

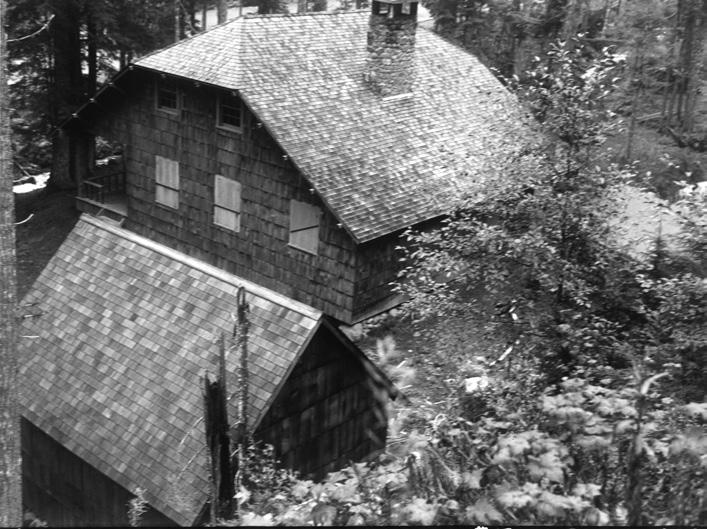

Our Mountain Home: 100 Years of Mazama Lodges, p. 33

COLUMNS

Mazama Values, p. 4

Mazama Membership, p. 5

Interim Executive Director’s Message, p. 6

President’s Message, p. 7

Successful Climbers, p. 8

Upcoming Courses, Activities, & Events, p. 12

What’s Happening Around the Mazamas?, p. 13

Mazama Classics, p. 15

Book Review, p. 16

Saying Goodbye, p. 37

Colophon, p. 37

Executive Board Minutes, p. 38

It is shortly after the summit when my memory disappears. That’s what hypothermia does, when your core body temperature drops below a certain threshold. The blood stops flowing to the part of your brain where the memories form ..." p. 19

I realized that, unbeknownst to me, I had already climbed three of the necessary five peaks to qualify for this award. It seemed to me that the Emblem Peaks award was in reach ..." p. 29

The final construction of a 20 by 33 foot, two-story, timber-framed cabin at Twin Bridges in 1923 marked an important year in Mazama history— the realization of the dream of a mountain home ..." p. 32

MAY/JUNE 2023 3

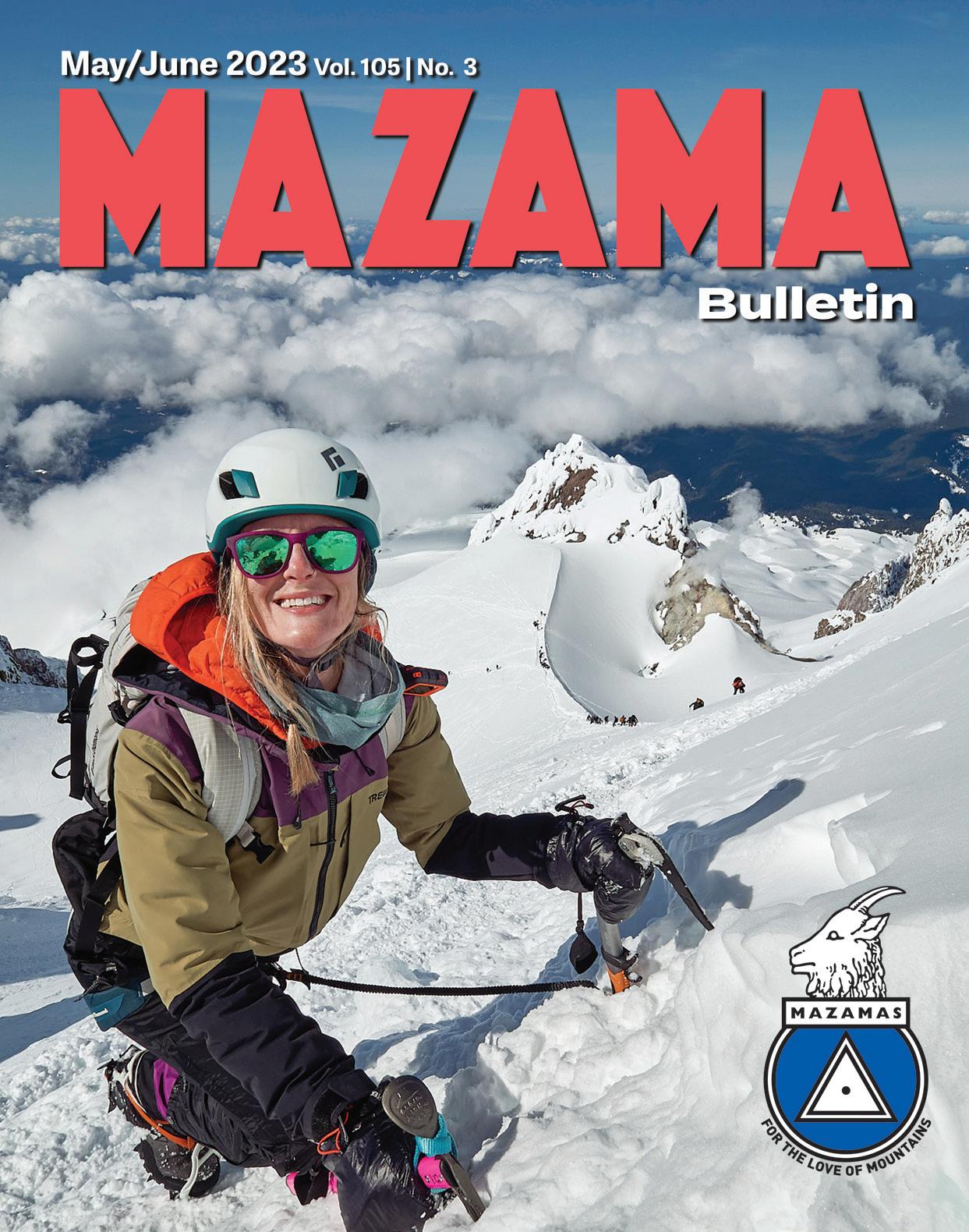

Cover: Laura Russell approaching the Pearly Gates, Mt. Hood, May 22, 2022. Photo by Ralph Daub.

Above: New member Nolan Gerdes on the summit of Gannet Peak, July 13, 2022.

MAZAMA VALUES

RESPECT

We believe in the inherent value of our fellow Mazamas, of our volunteers, and of members of the community. An open, trusting, and inclusive environment is essential to promoting our mission and values.

SAFETY

We believe safety is our primary responsibility in all education and outdoor activities. Training, risk management, and incident reporting are critical supporting elements.

EDUCATION

We believe training, experience, and skills development are fundamental to preparedness, enjoyment, and safety in the mountains. Studying, seeking, and sharing knowledge leads to an increased understanding of mountain environments.

VOLUNTEERISM

We believe volunteers are the driving force in everything we do. Teamwork, collaboration, and generosity of spirit are the essence of who we are.

COMMUNITY

We believe camaraderie, friendship, and fun are integral to everything we do. We welcome the participation of all people and collaborate with those who share our goals.

COMPETENCE

We believe all leaders, committee members, staff, volunteers, and participants should possess the knowledge, skills, abilities, and judgment required of their roles.

CREDIBILITY

We believe we are trusted by the community in mountaineering matters. We are relied upon for information based on best practices and experience.

STEWARDSHIP

We believe in conserving the mountain environment. We protect our history and archives and sustain a healthy organization.

4 MAZAMAS

FEBRUARY Membership Report

NEW MEMBERS: 8

Brad Avakian

Christopher Boswell

Chris Eubanks

Ian FitzGerald

Mi Lee

Finn Newman

Evan Spitzer

Carlos Stout

REINSTATEMENTS: 5

DECEASED: 0

MEMBERSHIP ON FEBRUARY 28:

2,618 (2022); 2,523 (2023)

Editor's note: Due to the elimination of the glaciated peak membership requirement, we will no longer be publishing the names of qualifying peaks with new members. For those who have summited a glaciated peak, or intend to climb one, we have created the Glaciated Peak Society (GPS). The only requirements for membership are you must be a Mazama member in good standing and you must have climbed a glaciated peak. All existing members prior to the January 31 bylaws changes will be inducted into the GPS. We'll be rolling out the Glaciated Peak Society in June.

MARCH Membership Report

NEW MEMBERS: 8

Robin Case

Nolan Gerdes

Reid Michael Kerr

Dzmitry Lebedzeu

Olivia Markee

Austin Pelkey

Andrea Pepitone

Tuller Schricker

REINSTATEMENTS: 3

DECEASED: 0

MEMBERSHIP ON MARCH 31:

2,662 (2022); 2,595 (2023)

MAY/JUNE 2023 5

MAZAMA MEMBERSHIP

Above: Left to right: Ralph Daub, Gary Ballou, Lisa Brady, Thuy Le, Kat Miracle, Nathan Taylor, Steven Williams, Michael Batryn, and Bridget Martin during a BCEP 2023 snow field session on Mt. Hood, April 8, 2023. Photo by Teresa Dalsager.

YOUR AD HERE! Contact us to learn more about advertising in the Mazama Bulletin! mazama.bulletin@ mazamas.org

INTERIM EXECUTIVE

DIRECTOR’S

MESSAGE

by Kaleen Deatherage, Interim Executive Director

For those who ski, snowshoe, and enjoy winter recreation, it’s been an amazing start to 2023. While for those of us who need the weather to improve a bit before we can get out and tackle the hikes and climbs we love, we are S.L.O.W.L.Y seeing signs of transition to the spring melt in the mountains and warmer temperatures.

But the weather outside has had no impact on the busyness inside the MMC. We have things going on just about every night and weekend these days. Check the calendar and get involved, opportunities to maximize your membership abound.

Speaking of membership, we want to help people around our community to spring into summer by joining the Mazamas. To encourage outdoor enthusiasts in our neighborhoods, at work, at the climbing gym, and wherever we interact with potential new Mazama members, we are running a special for the month of May.

From May 1 through May 31 we are waiving the $25 activation fee to become a Mazama member. We’ll be highlighting this throughout the next six weeks, reminding people in the eNews and sending it out via social media as well as messaging it via the communications channels of our partner organizations around the climbing community. Please help us out by asking those in your networks who are not yet members to consider joining during the month of May. Let's see how many new members we can add in 30 days. Can we set an all-time record for new members in a month?

Behind the scenes, our dedicated staff is here to help you. Let us know what information or support you need to recruit new members in the months to come. I can’t tell you all how lucky you are to have Mathew, Brendan, and Gina serving as your staff team. I am continually amazed at how much they know about the Mazamas, at their ability to find the piece of info or answer to a question that no one else can find, and their genuine interest in going above and beyond to make the Mazama member experience awesome. They’ve

taught me so much this past year, and I want each of you to know that as the executive leadership translation occurs this summer you are in good hands with a team of professionals who know what they are doing and who do it very well. Mathew, Brendan, and Gina, thank you. It continues to be my pleasure to work alongside each of you.

So without further ado, let's take all these tools we now have at our disposal— revised membership standards, an activation fee waiver, a high-performing staff team, and a genuine shared love for adventure in alpine spaces—and head out there to grow membership in the Mazamas!

MAZAMA MAY MEMBERSHIP EVENT

The Mazamas are waiving the membership activation fee for the month of May 2023.

Between May 1–31, ANYONE who joins the Mazamas will be able to do so without paying the $25 activation fee. Additionally, lapsed members can renew without the $10 reinstatement fee.

Membership rates for the month of May 2023 are as follows:

■ Regular: $72

■ Resides outside OR/WA: $54

■ Over 60 yrs of age + 5 yrs of membership: $36

■ Student: $36

■ Spouse: $36

■ Youth (under 18; living at home): $36

6 MAZAMAS

by Greg Scott, Mazama President

There are so many things underway this spring, it is difficult to highlight all of them. The executive director search committee received over 60 resumes in response to our March job posting. We whittled the candidate pool down to eight candidates who will receive initial interviews.

This will be followed by a second round of interviews in late April or early May, and a final round with the full board in May. We are on track to make an offer to a new executive director by the end of May and move on to the next phase in the Route Ahead. I am reassured we are on the right path by the fact several of the candidates cited our bylaws change as a reason for applying for the position. Concurrently, the board, staff, and Mazama members are beginning to lay the groundwork for our Lodge Capital Campaign. Thank you to everyone who responded to the survey that went out in the eNews in March. Special thanks to the Climb Committee for developing new policies for applying for climbs. Take a look for the updates in eNews and in this issue of the Mazama Bulletin. By the time this edition is published, BCEP will be winding down. I had the privilege to instruct with a group this spring and look forward to leading some climbs this summer. On a final note, I want to encourage everyone to be kind this

summer. Behind every volunteer and staff member is a person who merits respect, who has a life outside of volunteering, who is ceding time spent with their family, who is prioritizing the Mazama experience, and who is above all else dedicated to the mission of the Mazamas. Let's work together, and not against each other, to reach the summit in the Route Ahead.

MAY/JUNE 2023 7

MESSAGE

PRESIDENT’S

We have T-shirts, stickers, historic prints, & water bottles* MAZAMA MERCHANDISE ON SALE NOW! Order today at www.mazamas.org/merchandise *water bottles available mid-May

IT'S TIME TO CLIMB!

Mazama Climb Application Updates for 2023

by Mazama Climbing Committee

The 2023 climbing season is underway, and slots are filling up in the online calendar. There are some changes to the application process this year, so before you apply for a climb, please carefully look over these updates and general guidelines:

■ Because membership is now open to anyone, you must first join the Mazamas to apply for climbs, including Mt. Hood. Memberships are for individuals only, and do not extend beyond them. We do offer discounts for students, spouses of members, and youth. Please see the Join page at mazamas.org for more information.

■ Climbs are now free with the exception of Mt. Hood climbs. Most climb fees have been eliminated so the organization can avoid buying unsustainably expensive special use permits required in national forest wilderness areas. Since we continue to maintain a special use permit for Mt. Hood, we will continue charging for Mt. Hood climbs to cover this substantial cost.

■ Please keep in mind that climb leaders spend considerable time planning climbs and reviewing applications. Late cancellations can be very disruptive to a leader's preparation. Leaders work hard to ensure that climbs go with a full team. We realize that life happens and people may need to cancel. If you need to cancel your application, please do so as soon as possible to free up opportunities for other climbers and save the leader time reviewing your application. Please do not apply for multiple climbs of the same route, or to multiple climbs in a short time frame, with the expectation of canceling one climb in favor of another. If you've been accepted on a climb and need to cancel, contact the leader immediately so they can find someone to fill your spot.

■ Even though most climbs are now free, climbers are expected to pay for permits related to the climb. They may be required to buy permits directly or reimburse the climb leader. If a climb is canceled or an individual cancels, climbers will still be responsible for the cost of those permits and other costs incurred by the leader on their behalf. For example, leaders may obtain a reservation to car camp before a climb, and climbers should be prepared to reimburse leaders directly for that cost. Costs related to things like travel are to be worked out among the climb team members.

■ You can still find and apply to climbs by using the Climb filter on the Calendar page at mazamas.org.

Thank you for your attention. Now let’s go out and have a great year in the mountains!

SUCCESSFUL CLIMBERS

January 1, 2023–Mt. Hood, South Side. Pushkar Dixit, Leader; Shiva Kiran, Assistant Leader. Aardra Athalye, Rob Sinnott.

February 11, 2023–Mt. Hood, Devil’s Kitchen Headwall. Pushkar Dixit, Leader; Shiva Kiran, Assistant Leader. Walker McAninch-Runzi, Josh Pertile, Rob Sinnott. March 18, 2023–Mount St. Helens, Swift CreekWorm Flows. Chris LeDoux, Leader; Sergey Kiselev, Assistant Leader. Robin Case, Andrew Conley, Marcus Hecht, Erika Prats, Gabriela Sisco, Daniel Ugarte, Oscar Woodruff.

GLACIATED PEAK SOCIETY LOGO DESIGN CONTEST

Glaciers are hallmarks of life on Earth, supporting our planet’s ecosystems and influencing our day-to-day lives no matter where we live. Sadly, research shows that nearly half of the earth’s glaciers will melt by the end of this century, even if the world meets its most ambitious climate goals.

Anyone who’s ever stood atop a glaciated peak—Mt. Hood, Mt. Rainier, even Old Snowy—gets it can be a near-religious experience. It makes sense then that William Gladstone Steel, one of the founding Mazamas, was adamant that summiting a glaciated peak be a requirement for membership beginning in 1894.

It also makes sense to have eliminated that requirement in 2023 to allow our organization to adapt to a changing climate, become more inclusive, and welcome outdoor enthusiasts who are not necessarily alpine climbers.

For those who have summited a glaciated peak, or intend to climb one, we have created the Glaciated Peak Society (GPS). The only requirements for membership are you must be a Mazama member in good standing and you must have climbed a glaciated peak. All existing members prior to the Jan. 31 bylaws changes will be inducted into the GPS.

Help us design a logo for the GPS. The contest is open to individuals, organizations, companies, and educational institutions. You do not need to be a Mazama to participate, but members are encouraged to enter a design. Visit our website mazamas.org/gps for full contest rules.

8 MAZAMAS

MAZAMA REVERENCE FOR GLACIER SUMMITS REMAINS. HELP US CHERISH THEM.

OURAY ICE PARK

By Sarah Diver, Ben Fitch, and Brian Hague

By Sarah Diver, Ben Fitch, and Brian Hague

In the southwestern corner of Colorado, halfway between Grand Junction and Durango, lies the Ouray Ice Park, a destination crag of man-made ice and an excellent place to start one’s career in ice climbing. Our merry group of four current ICS students decided to venture there, taking advantage of the week-long break between field sessions, after two of us attended the Bozeman Ice Festival in December.

Far from any major airport, getting to Ouray might be the most challenging part of trip planning. We flew from Portland to Denver, Denver to Grand Junction, and then rented a car; driving an additional two hours to Ouray—taking the better part of a full day. Between crampons, mountaineering boots, and the 70-meter dry ropes necessary for climbing, the sheer weight of our checked luggage added an additional element of difficulty. Yet, other options for reaching Ouray were even less palatable: an 18-hour drive in midwinter from Portland, driving six and a half hours from Denver through notoriously

traffic-ridden I-70, or, comparably, flying to Durango (two hours) or Montrose (one hour). Despite the hardship, Ouray, self-proclaimed as the “Switzerland of America,” was certainly worth the journey. The city is nestled at the base of towering red sandstone canyons, arid pine forests, and snow-laden peaks stretching well above treeline into classic Colorado bluebird skies. The proximity of the canyon walls provides the town a sense of being cloistered, creating a very unique, nestled feeling.

We stayed at a comfortable and affordable Airbnb in town, within walking

distance from the famous hot springs and many great local bars and restaurants. It would not be a proper trip to Ouray without visiting Mr. Grumpy Pants, a rustic tavern favored by local climbers with a wood-burning fireplace and trad gear lining the walls as decoration. The ice park is located practically in “downtown” Ouray, which proved to be both a blessing and a curse. Much like our own Smith Rock, Ouray Ice Park is free, open to the public, and extremely accessible, with most routes available

continued on next page

MAY/JUNE 2023 9

via well-established bolted

Above from left to right: Ben Fitch on Riting (WI4) and Brian Hague on Schoolroom Pillar (WI5) in the School Room area of Ouray Ice Park, February 4, 2023. Photo by Ada Fisher.

anchors. And just like Smith during peak season, each morning brings a mad dash of climbers looking to put up an anchor before the best routes are taken. We soon learned having the driver drop off the team at the entrance so they could scout routes to be a winning strategy.

Another hurdle was simply navigating the park and learning the proper climbing etiquette inherent to its specific culture. While we did extensive research online ahead of time, our first day out required a bit of problem-solving and simply asking around. Ouray Ice Park comprises several discrete areas, each with its own geological features, ranging in length and level of difficulty. The routes are created through man-made water flow in the form of pipes at the top of the canyons. They are maintained by the park’s heralded “ice farmers,” who look after the conditions of the climbs daily and fatten the ice overnight as needed. We were surprised, if not bemused, by the somewhat haphazard means the pipes had been secured to the surrounding trees—but as they say, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it!” Luckily for us, the infrastructure of the ice park is well-maintained from ample signage designating the different areas to the metal catwalks and steel cables aiding cramponladen climbers to different anchors at the tops of the canyon ledges. Most routes are top-rope only with some areas designated as lead-only. Several of the harder climbs, like those in the Upper Bridge area, require top-managed belay stations. The climber is lowered into the narrow canyon and then belayed from above. So, you had better be confident in your ability to complete the climb—or at least confident in your belay partner, who would have to haul you out of

the canyon should you not be able to finish the climb.

On our first day, we stopped by the ranger station/warming hut to get a lay of the land. The anchors throughout the ice park are numbered to indicate the corresponding routes detailed on the website’s guide. Much to our surprise, the ranger informed us that the numbering system is all but defunct (we later learned a different guidebook not produced by the park had more information). We proceeded to simply set up top ropes depending on availability and perceived level of difficulty. Everything thus became a “WI-fun.”

Thanks to our Rocky Talkies and excellent communication skills learned through team sessions in ICS, we created a system where an emissary was sent to the base of a climbing area to scout an appropriate route, while the remaining team set up anchors on ground-level bolted stations. Our research ahead of time cued us into the fact that the anchor’s master points were often several feet from the anchor stations and usually lay over a walking path and the park’s water pipes. Fortunately, we brought two 30-meter dry-treated static lines that were both robust and easily adjustable to properly extend the master point. This method using static lines was the most common anchor type used in the park, and we highly recommend utilizing it.

We climbed many routes in the South Park area initially, where there were excellent WI2 and WI3 routes to practice our technique. We also explored New Funtier and the lengthier, slightly more interesting Schoolroom, where we were able to experience some easy mixed climbing and WI4s. On our final day, we took turns trying to climb a beautiful overhung curtain from a mixed feature,

10 MAZAMAS

Ouray, continued from previous page

which required placing a few ice screws for directionals.

Another delightful surprise was the camaraderie and openness of the climbing community in Ouray. On our second day, we encountered a group of Boeing engineers who set up a number of routes next to ours. We learned that it is not uncommon to swap routes with others nearby if their anchoring seems kosher. We were able to get a lot more climbs in this way and made fast friends. We also were able to route swap on our third day, so it definitely pays to chat your anchor neighbors up at the beginning of the day. Overall, our team progressed quickly in terms of both skill and efficiency because we worked well together, communicated clearly, and prioritized safety. This allowed us to get a lot of climbing done (and our muscles were grateful for the proximity to the hot springs). More so, it was extremely gratifying to feel safe and confident on our own after all of the effort to learn certain skills in ICS. We can’t thank the generous volunteers who passed on their knowledge and time to us through the various field sessions enough; they indirectly made this trip a success.

Living in the Pacific Northwest, easy and accessible ice climbs for beginners can be difficult to find—and certainly, it would be ill-advised to give ice climbing a try for the first time in an alpine environment, like on Devil’s Kitchen Headwall. Ouray Ice Park was not only a winter wonderland of beautiful and diverse ice routes, the

excellent infrastructure allows novice ice climbers with good anchor-building and sport climbing experience to gain valuable practice ice climbing in a safe and controlled environment. Not to mention, it was very fun!

Above

Above

RECOMMENDATIONS IF YOU PLAN TO VISIT OURAY ICE PARK:

■ Purchase the guidebook, Suffer Candy, Volume 1.

■ Arrive first thing in the morning when the park opens in order to secure the best routes. If traveling with a large group, consider splitting the cost of a membership ($200), which supports the great work of the park’s staff and allows access to the park 30 minutes before the public.

■ Teamwork makes the dream work. Divvying up the work of scouting for routes, setting anchors, and dropping people off at the walk-in entrance meant less time standing around and more time climbing the routes you want to climb.

■ Be cordial to your anchor neighbors for potential swappity-do’s (technical term) on routes.

REQUIRED GEAR:

■ Helmet, harness, and crampons.

■ 70-meter dry rope.

■ Two ice tools—I recommend the more aggressive tools specific for climbing vertical ice, such as the CAMP X-Dreams. Renting from Mountain Shop is by far more affordable if you are already checking gear bags than renting in Ouray.

■ Ice screws ranging in size for directional placement.

■ One 20–30-meter static line per anchor—the Ouray Ice Park website has a great video on how to set up anchors with static line.

■ Carabiners, rappel stuff, slings, and cordelette.

■ Various layers for staying warm and dry both on the wall and on the ground while belaying.

MAY/JUNE 2023 11

Facing page left: Ben Fitch on Schoolroom Pillar (WI5) in the School Room area of Ouray Ice Park, February 4, 2023. Photo by Sarah Diver.

Facing page from left to right: Ada Fisher, Brian Hague, Sarah Diver, and Ben Fitch, February 4, 2023. Photo by Mariah La Rue.

left: Ada Fisher on Schoolroom Pillar, February 4, 2023. Photo by Brian Hague.

right: Sarah Diver on Schoolroom Pillar, February 4, 2023. Photo by Brian Hague.

UPCOMING COURSES, ACTIVITIES, & EVENTS

2023 CANYONEERING

Registration closes: May 2

Course dates: May 25–July 30

This six-week course includes weekly lectures and two field sessions. The lectures will provide an overview of canyoneering, introduce canyon-specific topics and techniques, and prepare students for the class field sessions. An optional, latesummer outing will be offered to course graduates.

More at mazamas.org/canyoneering

SMITH ROCK TOP ROPE

Enjoy a day of top rope climbing at North Point of Smith Rock State Park on May 21, with some additional mini-lessons (8–10 minutes) that will include topics such as movement technique, traditional gear placement, and anchor building.

This activity is from 9 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. Please be ready at the trailhead and ready to hike at 9 a.m.

There are no climbing skills prerequisites for this activity—open to first-time climbers. You do not need to have any outdoor climbing experience, or even to have been to Smith Rock before.

More info and registration at tinyurl.com/ SmithTopRope

ROUND THE MOUNTAIN RETURNS

Yes, it is coming round again. Save the date for another fun-filled, Round the Mountain adventure over Labor Day Weekend, Sept. 1–4, 2023. Details are still unfolding as of our deadline, but it is happening.

We’ll be setting out on our 3-day, 13–14-mile-a-day trek from our base camp at Mazama Lodge, carrying only daypacks. Each night, hikers are returned to the lodge for food, hot showers, a cozy bunk, and camaraderie.

This adventure will include meals, lodging, and shuttle vans transporting hikers from our meeting place in Portland to the Mazama Lodge, as well as to/from the trailhead each day.

2023 STEEP SNOW & ICE

For the more advanced climbers drawn to snow and ice, this class aims to provide a solid foundation for tackling many challenging snow and ice routes often just around the corner from well-traveled routes.

More details in "2023 Steep Snow and Ice Skill Builder Set for August" on page 27.

SAN JUAN OUTING

Dates: September 11–18, 2023

Cost: $1,089 members; $1,239 nonmembers

Join the Mazamas for a 7-day outing in the San Juan Mountains of southwestern Colorado where we will enjoy daily B- or C-level hikes. Our first day will take us to Mesa Verde National Park where we will hike among the famous Anasazi ruins. We then drive along the Million Dollar Highway, recognized as one of the most scenic drives in the country, through the Victorian era preserved mining towns of Silverton and Ouray, the latter dubbed the “Switzerland of America.” We will also visit the upscale nearby town of Telluride where we will enjoy more fabulous hiking. Our hikes will be in beautiful alpine settings surrounded by mountains reaching above 14,000 feet yet close enough to each of the towns to allow post-hike explorations. We will be staying outside the town of Ridgway in a gorgeous modern and spacious chalet on 35 private and wooded acres at nearly 8,000 feet, atop a mesa with spectacular views of the surrounding mountains.

12 MAZAMAS

WHAT’S HAPPENING AROUND THE MAZAMAS?

ADVENTEROUS YOUNG MAZAMAS:

■ Recently hosted hikes, a snowshoe outing, a pub night, and a club night. Have new hike leaders in the pipeline and are planning more events accordingly.

BASIC CLIMBING EDUCATION PROGRAM:

■ BCEP teams got a staggered start beginning in March. T-shirts were printed and are being distributed at press time.

NOMINATION:

■ At press time, the committee had scheduled a meeting with a board representative to learn about how the recent changes in the bylaws affect elections and recruitment. Until then, most of its activities were placed on hold.

FIRST AID:

■ Alicia Antoinette joined the committee.

■ Alex Danielson completed WFR.

■ Patricia Troy has been recommended to Base Medical as a Lead Instructor.

PUBLICATIONS:

■ Published its first-ever issue celebrating the role of the arts in the organization’s history and in the lives of members.

■ Looking for more advertisers for the bulletin.

■ Asks members to submit reports and stories on their activities and initiatives.

CLIMBING:

■ Held a climb leader update regarding the effects of new bylaws. Continued updating the leaders with scheduling information and best practices.

■ Working on leadership development equivalencies and alternate pathways to teaching.

NORDIC:

■ Transitioning chair from Freda Sherburne to Lindsey Addison.

■ Both Stop the Bleed in February and the MFA course in March were enormous successes. Volunteer patients with MFA benefited from a new video training program.

■ The MFA badge is now valid for only two years, rather than three.

■ Offered five climb leaders who registered for MFA an additional Patient Assessment workshop.

■ Opened a discussion with CISM and the American Alpine Club Grief Fund on the role of psychological first aid in the committee’s curriculum.

■ Working with staff to resolve a problem with the badge request system not accepting update requests.

OUTINGS:

■ Restructured fees and per diem rates for activities for members, non-members, and leaders, and to make outings more profitable for the organization. Currently working on updating the Outings Handbook to reflect these changes.

■ Hoping for updates from Washington’s national forests regarding scheduling climbs in them.

■ Working on updating the Trail Trips Manual to include Nordic activities.

INTERMEDIATE CLIMBING SCHOOL:

■ Concluded its 2022–23 program in early March with the skills assessment.

■ Many graduates assisted in BCEP.

■ Jessica Minifie and Toby Contreras will coordinate the next ICS.

■ Ann Marie Caplan joined the committee.

MAY/JUNE 2023 13

THE DARK SIDE TO SAFETY CULTURE

y Ryan Abbott, Critical Incident Stress Management Committee

Have you ever wondered what makes an action healthy or unhealthy? It seems like everywhere we go in our lives we’re surrounded by judgment about what people are supposed to do or not do. Somewhere between the black and white of good and bad or healthy and unhealthy are circumstances with varying shades of gray and seemingly paradoxical logic, where normally good things are suddenly bad or unhealthy.

Actions can rarely be judged in and of themselves, nor can they always be judged by their outcomes. You may not like the end result, but that doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with the actions themselves. And other questions tend to come up, such as what’s good and bad, and for who? Who gets to be the judge of that, anyway? Homicide is generally considered to be wrong unless you were forced to do it to protect your life or someone else’s. In this case, it’s tragic but necessary. And some things happen over a spectrum. Exercise is healthy unless you do too much of it and wind up with an overuse injury. The complexities of our lives are typically defined by our intentions, our actions, the outcomes, and the context they were done in. Each of those categories is complex enough by itself. The place where they collide can be even more daunting to unravel, not to mention the distortions in our perception.

As mountaineers, we engage in a sport where we can die doing everything right. The consequences of being wrong, unsafe, or just plain unlucky can be deadly. To mitigate the high stakes, we develop safe methods, practice skills, and learn anything that can inform our actions to ensure a safe outcome while still enjoying the wilderness. We put our trust in the people we’re with. We value safety. Period. The Mazamas embodies that value. We’ve taken on this mantle to prevent accidents. What could be so bad about that?

Turns out, there’s a dark side to safety culture, and we’re better at preventing accidents than we are at addressing them when they do happen. Everything I’m going to say for the rest of this article will seem simple and logical from the comfort of whatever chair you're reading this from, but trust me, when I say that if you are someone who is involved in a

climbing accident, there’s nothing simple about it. You’ll feel like you violated some fundamental law or “the code.” Victims can feel like perpetrators or burdens. Leaders might feel like failures and responsible for what happened to the climbers who were with them. Some are left just trying to make sense out of it all and are ready to find the (or any) cause that can be assigned and corrected for next time, if they decide to climb again afterward. Sometimes the trust or the perception that you have about others trusting you on the mountain is shattered. Blame, guilt, and shame spread like a contagion. Then, as if the trauma of the accident wasn’t enough of a problem, we wind up adding more problems that seriously impact our mental health and our ability to recover from what happened.

So, what are we to do? Stop taking safety so seriously? Confine ourselves to a couch? Only a Sith thinks in absolutes. Instead of losing your attention thus far into an article, I think I’ll just cut to the chase. Part of addressing recovery from an accident deals with the work you’ve done before you even set foot on the trail. Regarding what’s being discussed in this article, we have to come to terms with the things inside those complex categories I mentioned earlier. Let’s scratch the surface of that reality with a few pointed points:

■ We perceive ourselves as having more control in the mountains (or over any circumstance in general) than we actually have. Some incidents in the mountains are easily beyond our ability to predict, prevent, or react to.

■ We are human and therefore fallible, no matter how experienced or knowledgable we are (or think we are). Sometimes being experienced and knowledgeable is exactly how we blind ourselves to our ability to predict and control outcomes.

■ People often want to make sense out of bad things and assign a cause. Sometimes that's a piece of gear, a method, conditions on the mountain, or a person. It’s part of how we’re wired.

■ Accidents are considered a statistical inevitability.

To summarize the list, bad things are going to happen and we’re all just people doing the best we can at any given time. And that summary is our way through the quagmire. We don’t need to compromise our culture of safety or make changes to the way we climb in order to increase our odds of healing from an incident. Our relationships and our own sense of self don’t have to be sacrificed, either. It’s much easier to neutralize the issues before they become problems. To begin negating this specific set of problems before having to face them after an emergency, try the following:

■ Meet reality on its terms and recognize that our brains are full of cognitive limitations and traps.

■ Challenge your perceptions and assumptions.

■ Foster a sense of forgiveness and compassion for yourself and extend that to everyone else.

■ Be active and explicit with your support. Don’t operate under the assumption that certain things don’t need to be said to be understood. Unspoken assumptions can be insidious and have a way of being twisted into terrible interpretations by the person who is struggling. I would recommend just coming out with it, however awkward it sounds. Perhaps it just sounds like, “I don’t blame you. I still trust you.” Remember that there is a big difference between the support you actually have and your perceived level of support. Often a person going through

continued on next page

14 MAZAMAS

something difficult where they feel at fault will perceive less support than they actually have. That makes it more important for the people around them to speak up and support them, even when it seems like that support is obvious.

It’s quite a gift to be able to understand yourself and others as they are. More so to forgive yourself or to be forgiven by those around you. Fostering that compassion in a community can strengthen it, insulate us from harm before things go sideways, help us to process negative events (or at least not add more problems to the problem), open up new choices, and will go a long way towards enriching other areas of our lives, too. So, don’t go backward on our safety culture, just include something new. Or at least make it more obvious.

The Mazama Critical Incident Stress Management Committee wishes you all safe climbing as the fair conditions of this spring climbing season approach. If you experience something difficult on your adventures and need a way to process or start recovering from it, we’re just an email away. Anyone can ask for a debriefing and our team is trained to help.

CISM Committee

cism@mazamas.org

MAZAMA CLASSICS

For members with 25 years of membership, or for those who prefer to travel at a more leisurely pace.

We lead a wide variety of year-round activities including hikes, picnics, and cultural excursions. Share years of happy Mazama memories with our group. All ages are welcome to join the fun.

■ On Tuesday, July 4, Dick and Jane Miller will be holding a summer picnic at their home. Classics and other Mazamas are welcome to attend. The event is free but attendees are asked to bring a salad, main dish, or dessert to share. Dick and Jane will provide plates, cups, utensils, napkins, and water.

□ The event begins at noon with food at 1 p.m.

YOUR AD

□ Address: 17745 SW Cooper Mountain Drive, Beaverton, OR 97007

□ Please follow signs from SW 175th Avenue to the parking area. Park and bring your food to the dining area.

CONTACTING THE CLASSICS

Contact the Classics Chair, Gordon Fulks at classics@mazamas.org.

SUPPORT THE CLASSICS

The Classics Committee needs a volunteer to put more content in our column on a quarterly basis. We want to document past Classics events and make sure that our postings to the web are current and complete. More generally, there is always work to be done on the committee. Our meetings are the fourth Monday of every other month at 11 a.m. on Zoom. Email classics@ mazamas.org and tell us how you can help.

CLASSICS COMMITTEE MEETING

Keep an eye on the Mazama calendar for our next meeting.

MAY/JUNE 2023 15

HERE! Contact us to learn more about advertising in the Mazama Bulletin! mazama.bulletin@mazamas.org

Karina: 503-230-1340 $49,000 For Sale: ½ share of forest cabin Rustic | Off-grid | GPNF | 1.5 hrs from Portland Bordering a Wilderness Area Great for hiking, relaxing, & mushrooming

BOOK REVIEW

Classic Cascade Climbs: Select Routes in Washington State by Jim Nelson, Tom Sjolseth, and David Whitelaw

by Ryan Reed

Given the volume of crowd-sourced information online, one might expect printed climbing guidebooks to be headed the way of the phone booth. They aren’t, and that’s a good thing: climbers still recognize the value of expertise and appreciate the context books can provide on history, geology, access, and local ethics. Climbing apps, websites, and forums are invaluable for fine-grained beta and updated conditions, but guidebooks remain the best source for foundational data and, above all, inspiration.

So, it’s great to see Mountaineers Books publish a new, and utterly gorgeous, version of an outstanding resource for Northwest climbing. Classic Cascade Climbs (2021), created by Jim Nelson, Tom Sjolseth, and David Whitelaw, is a single-volume update of the two-volume Selected Climbs in the Cascades (1993 and 2000, with revised editions in 2003 and 2004) by Nelson and Peter Potterfield. Despite the different titles, the two series share a similar approach, layout, and style. On the other hand, the authors added so many new climbs that it’s essentially a different book; no Cascade climber should be throwing away their well-thumbed copies of Selected Climbs.

When the first volume of Selected Climbs was published in 1993, the idea of rating climbs by their appeal, rather than difficulty or location, was relatively new. Fred Beckey’s three-volume Cascade Alpine Guide (1975–2008) aimed at comprehensiveness: every known route on more than 1,500 peaks and high routes. Beckey makes plenty of quality judgments, but you have to wade through 2,000 pages to find them.

Nelson and Potterfield took a different approach. “It was our intent to highlight the finest, most aesthetic, and most enjoyable of Cascade climbing routes, regardless of difficulty,” they wrote in the 2003 edition. The eclectic mix bothered some reviewers, but climbers took to it, and many of its then-obscure routes have since become well-loved classics. Its success prompted both a second volume and revised editions. It’s common to hear Northwest climbers cite “Nelson-

Potterfield,” alongside “Beckey,” when discussing routes.

For the new book, Nelson, a guide and Seattle mountain shop owner, worked with Whitelaw, a climber and author of Weekend Rock: Washington, and Sjolseth, the first climber to complete the Kloke list of the hardest Washington summits. Although it’s clearly an update to Selected Climbs, the new guide covers a lot of new ground; only 30 of its 100 climbs are full repeats from the earlier volumes.

Like Selected Climbs, Classic Cascade Climbs is aimed primarily at experienced climbers with trad rock or ice climbing skills; only a handful of routes are pure scrambles or snow climbs. (Those looking for nontechnical summits are better served by Jeff Smoot’s Climbing Washington’s Mountains or the Oregon and Washington Best Scrambles series). The focus is not peak-bagging; most routes reach a summit of some kind, but not always a well-known one. Many routes are challenging traverses of multiple summits.

The book is organized by areas or individual mountains, each with a brief discussion and a climbing history (including some terrific personal anecdotes), followed by descriptions of one or more routes. As in Selected Climbs, approaches are discussed and graded separately—particularly useful for North Cascades objectives. The routes themselves get useful but limited descriptions—a fine choice, considering the wealth of beta available on websites like SummitPost and Cascade Climbers; it likely also reflects

an aversion to “beta spraying.” Annotated photos and a few climbing topos help visualize the routes.

The biggest upgrade here is the photography; Selected Climbs was all black and white, Classic Cascade Climbs is full color. The authors make great use of John Scurlock’s aerial photos and dozens of others from the likes of Steph Abegg, Lowell Skoog, Colin Haley, and Max Hasson. The photography and quality printing, in fact, make this almost a coffee table book, appealing both to armchair climbers as well as those researching routes.

The real value for climbers is the curation: here are three experts recommending 100 routes as exceptional. There are many not found in the earlier volumes: a half-dozen bolted alpine routes (including Nelson and Whitelaw’s own Tooth Fairy), more alpine ice routes, and several new climbs in the Pickets and the Pasayten Wilderness. There are valuable discussions of lesser-known objectives like Reynolds, Tenpeak, and Fernow.

It’s clearly no easy task to whittle down the 182 routes in Selected Climbs to just

continued on next page

16 MAZAMAS

100 while adding new ones. The authors wisely drop most of the rock and ice crag climbs that fleshed out the second half of Volume 2, leaving more room for alpine routes. But a lot of great climbs from Selected Climbs didn’t make the cut, including a few of my own favorites—East Wilmans Spire, Mt. Thomson, and the Southwest Buttress of South Early Winters. Gone too are Black, Cutthroat, Sharkfin, Sherpa, Unicorn, Triumph, and other well-known moderates.

In fact, the challenge level for many routes in Classic Cascade Climbs is markedly higher than in Selected Climbs. Some routes clearly stretch the concept of “classic,” to the extent the term suggests widespread validation—for example, a route on Mt. Garfield that has only a single known ascent. The authors also added a number of spectacular traverses; in addition to the well-known Ptarmigan and Torment-Forbidden traverses, there are the 14-peak Picket Fence and Gunrunner traverses, which were pulled off by crack teams only in the last two decades. Looking for the basic route up Snowking Mountain? It’s been upgraded to a 45-mile traverse from Buckindy.

In making their more challenging selections, the authors aren’t simply tracking the accomplishments of higher-end mountaineers so much as suggesting the range of possibilities beyond peakbagging and route-ticking. They seem less interested in updating a canon of “classic” routes than in encouraging the kind of exploration and freedom that characterized their own careers. Spend some time leafing through this gorgeous guidebook/coffee table book and you’ll find plenty of specific routes to seek out, but you’ll also get a sense of the vast array of options these mountains offer.

There are a few ways the new volume falls short. The brief introduction is underwhelming, with a smattering of trivia on volcano names and the Bulgers list. There’s no clear statement of the book’s goals—presumably to profile the finest routes, regardless of difficulty, to paraphrase from Selected Climbs. The photographs are stunning, but most of Scurlock’s aerial photos show winter conditions, which can clash with summertime route descriptions. Finally, the inclusion of a few well-traveled and exhaustively documented routes on Mt. Hood, Mt. Adams, Mount St. Helens, and Mt. Rainier seems like a misuse of limited space; why not start at Snoqualmie Pass and title the book “Classic North Cascade Climbs?”

Still, Classic Cascade Climbs fills a distinct niche: it’s thrilling in a way Selected Climbs is not. The latter remains a valuable resource in the search for specific objectives, and has a lot to offer climbers seeking moderate routes. The new volume has its share of those, but it’s also a trove of inspiration, embodying a more exploratory spirit than most guidebooks. As the authors say, the Cascades harbor “more secrets than can ever be known,” and they encourage readers to “hike up to where everyone else turns right, put this book away, and hang a left!”

THE MAZAMAS WANT TO HELP YOUTH & FAMILIES GET OUTSIDE

by Gina Binole, Mazama Office & Communications Coordinator

Perhaps you’re already an outdoor enthusiast who’s been a Mazama for years and hope to share your passion for adventure with your family. Or maybe you’re all new to the natural magnificence of the Pacific Northwest and wish to explore together. Regardless of your situation, the Mazamas can help you get outside.

Our Families Mountaineering 101 program trains adult and youth climbers for entry-level mountaineering activities, including rock and snow climbing skills. FM101 gets the entire family involved with alpine activities and mountaineering objectives.

Family-friendly hikes and climbs are a great way to explore trails together, discover and delight in PNW splendors, and challenge yourselves individually and collectively. Together, families can reap the physical and mental health benefits from these endeavors. Look for them on our calendar.

Youth camps are a great way for children to develop and nurture their relationship to nature, boost their confidence outdoors, and learn to climb. We’ve partnered with Northwest Outward Bound School to bring campers back to the Mazama Mountaineering Center this summer. All children ages 10–14 are welcome to attend. Visit www.nwobs.org to learn more and register.

Plan and learn about the outdoors together in the Mazama Library, recognized as holding one of the top mountaineering collections in the country. Located on the ground floor of the Mazama Mountaineering Center (527 SE 43rd Ave. Portland), the library boasts more than 10,000 books, magazines, and journals. It’s a fantastic resource for members of the general public to find information on hiking, camping, and exploring the rich history of regional and global mountaineering culture.

MAY/JUNE 2023 17

LEARNING TO CLIMB!

Mazama Families Mountaineering 101 testimonial

by Arshi Purohit

by Arshi Purohit

My name is Arshi Purohit and I joined the Mazamas when I did the Families Mountaineering 101 course. When we started, we didn’t know if we had the appropriate gear, so we brought all of our indoor climbing gear to FM101 “gear night” at the Mountain Shop in August. The people there were very kind and supportive. We learned how outdoor harnesses are different from indoor ones and about climbing shoes.

In September, our first lecture was fun and the volunteers teaching were thoughtful and helpful when we didn't understand something. I learned how to tie climbing knots. I had trouble with my prusiks because it was really hard to get my equal signs and Xs next to each other. Eventually, I got the hang of it.

Our first field session was in October at Horsethief Butte in Washington. It was a long drive but we arrived just in time and were ready to hike. There were small steps made of stone, so going uphill was easier. I found it harder to climb outdoors than indoors; there weren’t many easy handholds and some rocks were hard to get past but I still got to the top. I belayed my partner who was similar to me in weight. It's harder to belay someone heavier than you so you need an anchor. The camp we stayed at was really cozy and we shared a great potluck meal with the entire class.

My favorite was the rappelling class. Rappelling down the wall was exciting and terrifying at the same time. A Mazama volunteer helped me through the stepoff and stayed at the top once I was done

rappelling down. I also learned to use my prusiks to climb up a rope! Just going up two feet was really exhausting, but the rope kept me safe.

I got to learn about using the compass in the navigation class and learned that in the late 19th century the magnetic north pole was farther than it is now. We don’t use compasses as frequently now. Our field session at Mt. Tabor was cold and beautiful with amazing green grounds in November. We paired up with another group and it was exciting to use the map!

Next was first aid. What is the key to surviving when you have a wound? Along with others in my age group, I learned to make a splint on a broken leg. We also got to brainstorm ideas on how one can get injured or die in the wilderness.

In January, we had lectures about avalanche safety and snow climbing. I loved asking questions and learning more details. After a few weeks, I felt prepared for our snow field session in February. We practiced in the snow a short climb from the Timberline overflow parking area. That Saturday at Timberline was the most tiring

day of all. It was hard to tie knots with or without mittens in the snow. The easy part was going up the path to the Mazama Lodge. Once I got there, a quick tour amazed me. There were tall bunk beds in the rooms! On Sunday we learned to travel as a team on a rope in the snow. I was the person at the end picking up the pickets but had to wait for everyone to get clipped past the pickets ahead of me. I learned that using carabiners wasn’t as safe as passing our knots through the picket. Our teacher made us work hard to help us learn. When one of the adult teams went over a bump really slowly, my team of kids threw snowballs at them for amusement.

I’m really glad I got into FM101. I made new friends and we had a lot of fun. All the instructors and assistants were willing to help me so I could learn about mountaineering. Through all of the hard work—especially with my father and I together—I was able to learn something amazing that I wouldn’t have learned otherwise.

Thank you, Mazamas!

18 MAZAMAS

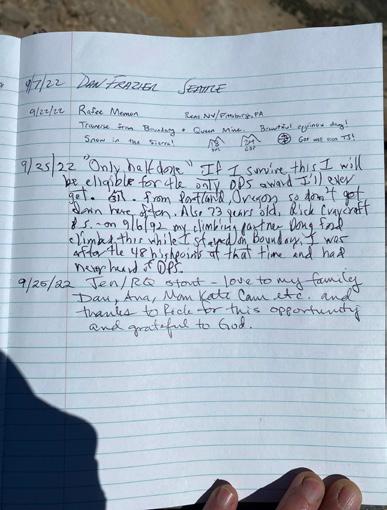

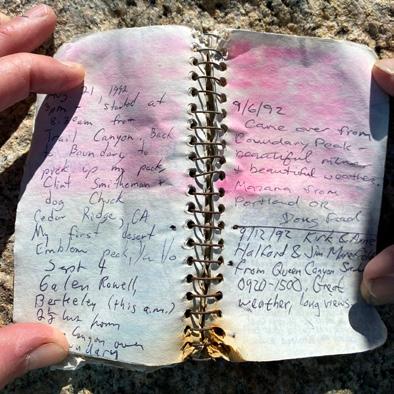

THE MOUNTAIN KEEPS THE STORY

by Laura Westmeyer

Sometimes I think about Laura up there, on Mt. Baker. I wonder how she managed to clip through the handful of pickets to keep herself on the fixed line. Why she didn’t, in her disoriented state, and with frost-nipped fingers, unclip the lanyard and slide into the whiteout, off the steep slopes of the Squak Glacier. I wonder where she got the scratches on her side, the bruises on her back, or the swelling that stayed in her purple knees for the weeks after the race. Most of all, I wonder what thoughts were running through her head, right before she wrapped her arms around her knees, tucked her face into her chest, and stopped moving.

continued on next page

That’s how they found me. Unresponsive, at 9,200 feet, on the side of Mt. Baker. I had just summitted Sherman Peak, and was descending back to Concrete, Washington, a town about 9,000 feet below and 28 miles away. It was where I had started off on foot, nine hours before. I was in the 2022 Mount Baker Ultra.

The Mount Baker Ultra is a 56-mile ultramarathon. A mountain foot race with three parts: an uphill running section, a mountaineering section, and a downhill running section. The starting point is a small town that lies just above sea level, in the Skagit River Valley of the North Cascades. The event begins at midnight. Runners race through the night on gravel roads, covering 3,000–4,000 feet over about 20 miles until they hit the snowline. There, they change into mountaineering equipment, and continue their climb up the mountain. The 10,160 foot summit of Sherman Peak marks the halfway point of the race; once at the summit, the runners descend along the same route, continuing down the mountain to run the final 20 miles back to Concrete to the finish. The race is a current-day homage to a foot race that took place from 1911 to 1913 over the same terrain. According to the race director, it is the only race in the world that ascends a glaciated volcano.

I had learned of the race primarily through Ryan Johnson, a Mazama climb leader, experienced ultra runner, rock and alpine adventurer, and one of my closest friends. Ryan had encouraged me to sign up for the Mount Baker Ultra, about eight months before. I was immediately intrigued by the mandatory gear list, which included a climbing harness, crampons, helmet, and an ice axe; this was not your typical ultra packing list. I looked at past years’ results and was fascinated by the number of people who had attempted the race, and not finished; the low number of female participants; and the high percentage of people who signed up repeatedly, regardless of whether they had completed the race in prior years. I loved mountaineering and trail running, and was developing a new passion for ultramarathons. This would be an event that combined those joys, in an organized race setting. And because it was an

organized race, it would bring with it the unique opportunity to move light, fast, and free. I was in. I told Ryan it would be the craziest thing I’d ever do, submitted my qualifications, and registered for the race.

When we checked in on race day, we were assigned bib numbers. Mine was 56. “That’ll be easy to remember!” Ryan said with a grin. “It’s the number of miles we’re running.” I looked at the time. Almost 11 p.m. We had an hour until the race began. We took pictures, fiddled with gear adjustments, did a warm-up jog, and talked excitedly with other racers about the day ahead. I got a text message from a friend in Bellingham, wishing me luck. The day before, he had told me the area was getting pummeled with rain. “Monsoon rains,” my friend had described. He wondered whether the race was still happening.

We were concerned about the weather. Back in Portland, we’d had heavy rains all month. Forecasters reported it was the

wettest Portland May since 1941, and the tenth wettest on record. In the North Cascades, Mt. Baker had gotten several feet of new snow in the weeks leading up to the race, and only more was coming. I had checked the forecast nearly every day in the two weeks leading up to the race. High winds. Snow flurries. Cloudcover. Storms. We certainly wouldn’t be expecting any views. The mountain forecast looked even worse at the summit. We would be going into sustained, high winds at the top. Moderate rain and snow at all levels, with the freezing point hovering around 9,000 feet.

My typical mountain outings are centered around the process of exploring, connecting with others, the beauty of being outdoors, and the joy that movement brings. Speed is not usually a focus. But this was a race. I had put a great deal of thought into how to move most efficiently, and most quickly, in each stage of the event, and had borrowed, acquired, and tested lightweight equipment in preparation for the day. But with the forecast unwavering, and after talking it through with Ryan, I decided to instead use my heavier, warmer, mountain equipment. Heavier gear would mean slower movement. But far better to be dry and slow, and have a chance at actually finishing the race, I thought, than to be wet and cold and have to turn around. We were here to finish the race.

We laced our shoes and toed the start line. While there’d been a brief reprieve in the evening hours, as if on cue, when the gun went off, the skies opened. First, it was a soft sprinkle. Then the sprinkle turned to rain, and the rain turned to pour, and the pour was as constant as our climb to the base of the mountain. When we reached the snowline, every inch of our bodies was wet, every fiber of clothing saturated.

I had a towel and a fresh set of clothes waiting for me at the snowline, in the heated tent at Aid Station 3. I dried off, changed from head to toe, and packed my mountain bag. Immediately as I left the aid station, I regretted my decision to take the conservative approach to gear choices. My shoes felt much heavier than the ones I had hoped to wear. My backpack was full of what I thought was surely too many clothes. My mind flashed to the first aid, snowshoes, crampons, helmet, water, and

20 MAZAMAS

The Mountain, continued from previous page

Above: Volunteers at an aid station on Mt. Baker during the race. Taken from Mt. Baker Ultra Instagram post. Previous page: Laura Westmeyer approaching the summit, with the hand of Sam Waddington reaching out to give a fist bump.

Photo by Sam Waddington.

sandwiches I carried, and I kicked myself for bringing too much weight. I didn’t need to bring so many extra clothes, I thought to myself. Or so many snacks.

Three hours later, I took it all back. I had been climbing steadily at a consistent, moderate pace, and was feeling good. I passed a couple of runners on the route. They looked cold and wet. I considered whether I was cold. No, not really. I had my helmet and winter ski goggles on. I was moving quickly enough to generate a fair amount of heat, and was bundled with breathable wool that kept me cool even as I perspired through it. I was grateful I had brought so many clothes. It was still raining relentlessly. I wondered whether we would be here, if it weren’t for the race. No; we would have turned around, and saved Mt. Baker for another day, I concluded.

When I reached Aid Station 4—a key transition spot, and the start of our glacier travel—I was surprised to learn that none of the runners had left yet. That meant that the first person on the fixed line would be the first person in the race. At this point, we were about seven hours in. I refilled on water, dropped off some wet gear, switched out my gloves, and hooked onto the fixed line. I was the third runner on the line. As

I left the aid station, I heard a volunteer remark, “I don’t think it’s a summit day,” as he looked ahead into the whiteout.

The weather was as predicted, and got worse the higher we climbed. It had rained consistently on the mountain, over the snow, up until we reached the freezing point at around 9,000 feet. Above that point, everything that had been rained on became ice, the rain became snow, and the winds blew at a constant, 60 mph sustained force. We were in whiteout conditions. If it weren’t for the fixed line, bright orange among the snow, I wouldn’t have been able to tell up from down. The harsh gusts slapped slush flurries across my face. My hiking poles, saturated from the past eight hours of rain, had become long icicles in my hands, that I was now unable to grasp. When I reached 9,800 feet, I had long stopped thinking about the race. The winds were fierce and the grade was steep on the narrow summit ridge to Sherman Peak. I dropped to my hands and feet in that final section, to get closer to the mountain, to feel more secure. I focused on putting one foot in front of the other. I thought about how close the summit was. Only a little ways more and I could head back down, and get out of this storm.

It is shortly after the summit when my memory disappears. That’s what hypothermia does, when your core body temperature drops below a certain threshold. The blood stops flowing to the part of your brain where the memories form. Hypothermia is defined as reaching a body temperature of below 95 degrees. The lower your core temperature gets, the more serious the symptoms become. In the mid 90 degrees, you might start to shiver. In the upper 80 degrees, your pupils enlarge, and your heart rate slows. Below 82 degrees, you lose the ability to reflex. Blood flow to your brain is significantly reduced. You become unresponsive.

I didn’t notice the first temperature drop. I didn’t experience any of the symptoms that would be characteristic of mild hypothermia. My body never shivered. I never felt cold.

I do remember the next drop, as I moved into a more moderate and then severe hypothermic state. The changes weren’t as much to the state of my body, as they were to the state of my mind. My eyes saw things differently. Textures had changed. Sounds were faded. The world continued on next page

MAY/JUNE 2023 21

Above: Typical gear used during the Mount Baker Ultra. Photo by Ryan Johnson.

was blurred, and my perspective rotated. It was as if I was entering a lucid dream. The snow, the ridgeline, everything around me was fuzzy. It felt surreal. People were moving in slow motion. The winds were silent, and then the sound came back on, as if someone had flipped a switch. I looked around slowly, with wonder and curiosity. It felt like I was seeing the world for the first time. I was seeing this world for the first time. I was aware that something had changed, but the change was not alarming. Despite feeling weird, I didn’t register anything as being off. Weird just felt like my reality. Strange, but comfortable. Unconcerning.

And then, as I drifted more deeply into a hypothermic state, I remember leaving this world, and fully entering the dream. I spoke to someone there. A race volunteer, who was asking if I was okay. I must have told him I was fine. My mind and body had separated, and I saw myself speaking not to him, but through him. I felt as if there were a glass wall between us, and that he was in a parallel world from where I stood. I remember thinking I was highly delusional. The world was fading. I continued down the mountain, fully aware and blissfully

Below:

Right inset: Laura at the start of the 2022 Mount Baker Ultra. Photo by Ryan Johnson.

unbothered that the place I was going wasn’t the place I had come from.

When my mind fully departed from the world, it wouldn’t return until about five hours later, when I came to in a tent at Aid Station 5. I don’t recall that final phase of hypothermia, and there are few accounts of my state of being during that time. But where my brain stopped remembering, technology has filled in some gaps. From my watch data, it is clear that I was struggling during that time, taking over two hours to descend hardly over 1,000 feet, where they found me for the rescue. My body temperature (taken from my wristwatch), overlaid with my heart rate, shows a graph with lines plummeting to an astoundingly low point, around the time I stopped moving.

I have no memory of those hours of struggle. I don’t remember the runner who found me curled against the picket, put his green jacket around me, and called out to the next person he saw to run to the next aid station as fast as possible and tell them to send a sled immediately. I don’t remember the three who lifted me onto a snowmobile as the driver hovered on the steep snow grade, and somehow kept

me on the sled with one hand as he drove through the whiteout a few hundred feet below, to Aid Station 5.

I don’t remember Steve, the volunteer who carried me into the tent. The one who, when I wouldn’t let anyone touch or get near me, grabbed onto me and pinned me to the floor with all of my cold, wet clothes on, while they wrapped a sleeping bag around us both and I fought with him hard for 20 minutes, clawing at him with my wet, gloved hands. But he didn’t stop, he just kept holding on, to try to get me warm. My watch data shows my body temperature doesn’t change much when I was first brought into the tent, but there’s a distinct spike in the minutes I was pinned down. There are many volunteers I owe my life to on that mountain. Steve is one of them.

In those hours in the rescue tent, I could be considered a textbook hypothermia case. The type you learn about in Wilderness First Aid classes. Highly combative and physically uncooperative. Trying to run out of the tent, into the snow. Unable to say any words, or know my own name. When I could finally speak, making no sense. My pupils were described as pinpricks. Jessica,

22 MAZAMAS

Left: Laura in a helmet with rescue volunteer Steve Zellerhoff putting his arm on her. Photo by Jessica Heidermann.

Laura's body temperature overlaid with heart rate, screenshot of watch data graph taken after the event. Right: Downtown Concrete, Washington. Photo by Laura Westmeyer.

The

Mountain, continued from previous page

the volunteer who was monitoring my condition during those hours, told me later they kept me in the tent for so long because they didn’t believe I would survive the ride to the snowline.

When my memory returns, I feel as if I just woke up. I am in Aid Station 5, around 8,400 feet. Three people I don’t know are tending to me. I’m wearing strange, soft, clothes that I don’t recognize as my own. I have a tube in my nose, for oxygen. There are moments of memory gap and suddenly I'm on a snowmobile. The driver points to a round handlebar and tells me to hold on with both hands. “Don't let go,” he tells me sternly. I feel so tired. I drift in and out of consciousness as we tear down the mountain, bumping mogul after mogul to the snowline. I was so cold on the sled. Volunteers at the snowline took me in a van to the nearest emergency room, the Skagit Valley Hospital in Mount Vernon, about two hours away. At the hospital, they immediately started pumping me

with warm IV fluids, covering me in a warm air "bear hug" suit. They weren't able to get a temperature reading on me for quite a while. After about six hours of warming up in the rescue tent, in the van, and after being filled with warm IV fluids and the bear hug, the first reading they got was 93 degrees. My core temperature is estimated to have gotten down to the mid-to-low 80 degrees before I became unresponsive. I was monitored overnight in the hospital while the race at Mt. Baker concluded.

Around 74 people started the June 5, 2022, Mount Baker Ultra. Fourteen of them made it to the summit. Just 13 finished the race.

It's a strange thing, to have no memory of a traumatic incident in your life. The experience has been dissociative, and I think of myself in the third person for much of it. Laura on the mountain. I see pictures of myself that volunteers took in the rescue tent, and I don't recognize myself in those images; she looks like a wild animal. But for several months after the Mount Baker Ultra, my fingertips remained numb, and my body carried an invisible weight that I felt every day, in every activity. I know that

even though my mind does not remember, my body does remember, and the mountain keeps the story.

It's been very helpful for me to journal, listen to others, and write out this story. As we approach the one-year anniversary of the event this June, and move through what has at times felt like a continuous winter of rain and snowfall, I find my mind transported back to that day, to the mountain, and what happened up there. For me, the 2022 Mount Baker Ultra is a poignant reminder that even when we do our best to prepare against them, there are certain risks that come with being in the mountains—risks that we cannot reduce to zero. And sometimes you get hit with the worst-case scenario. In this case, although I tried to prepare against the risk of hypothermia, I did get hit with a worst-case scenario. I feel incredibly fortunate that the right people were in the right place, at the right time, to deal with the situation and get me safely off the mountain. I owe my life to the volunteers at that race, and they will forever be a part of my story.

MAY/JUNE 2023 23

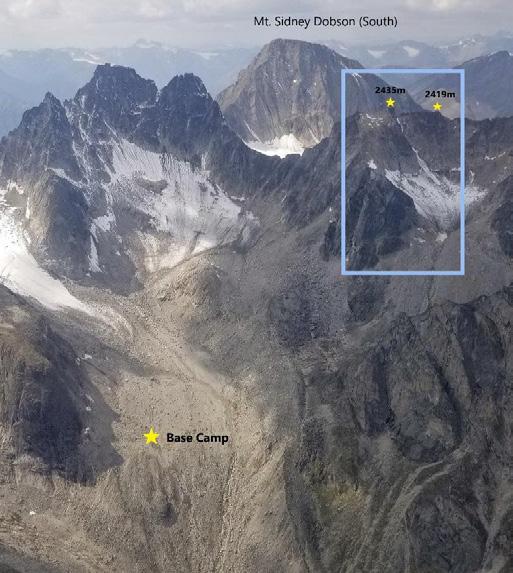

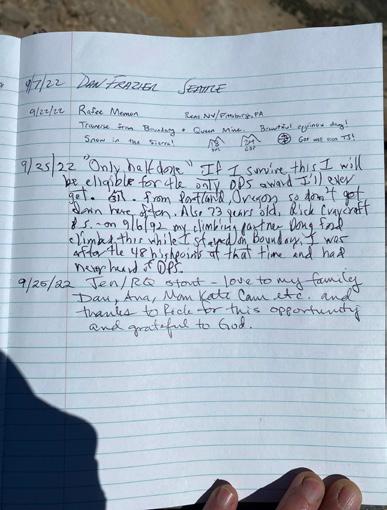

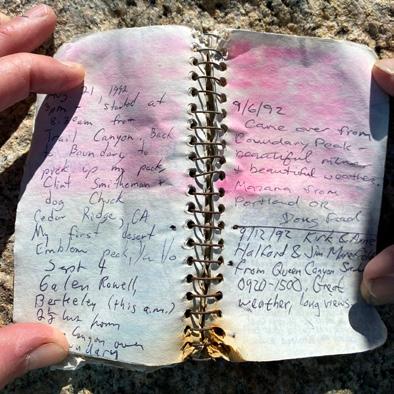

VARIOUS CLIMBS IN THE RAGGED RANGE

Northwest Territories, Canada

by Amy Pagacz

In early August 2019, Wojtek Pagacz, Katie Mills, Nick Pappas, and I flew into Nahanni National Park—a 30,000-kilometer reserve in Canada’s Northwest Territories. Funded in part by the 2019 Bob Wilson Grant through the Mazamas, we would spend two weeks exploring a small portion of the Ragged Range, just eight kilometers south of the well-known Lotus Flower Tower in the Cirque of the Unclimbables. We had hoped to find similarly solid granite spires; however, our surroundings were less inspiring, discontinuous, and loose.

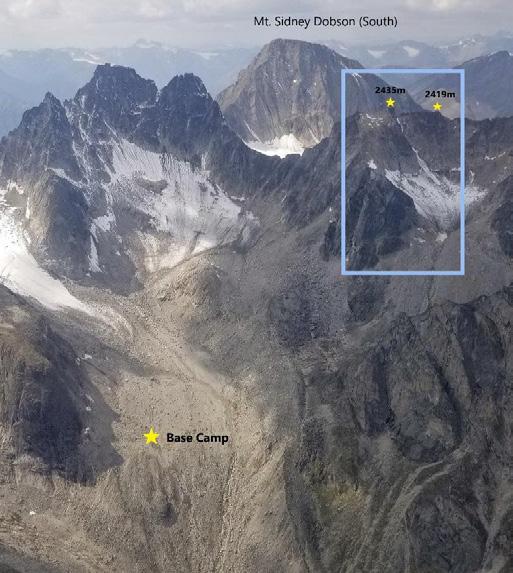

After a week of hiking in the rain and peering through foggy binoculars at nothing but mossy and very loose rock, morale was low. Wojtek and I made a plan to hike up into the westernmost cirque from basecamp to see if we could gain a ridge and press on towards Mt. Sidney Dobson, the most prominent and only named peak in the region. We knew from the helicopter flight into the valley that the peak itself was crumbly, but we needed an objective.

On our scouting hike into this cirque, we found a north-facing couloir that snaked down from a high col. A lack of rockfall gave us encouragement that the

couloir would provide safe passage through the otherwise loose rock. That night we messaged Nick Pappas and Katie Mills, who were in the valley below scouting an ambitious objective they called “The Chair,” and asked to borrow their ice axes. The next morning, after waiting out an early morning shower, we left camp armed with the camp’s four ice tools (two piolets and two technical tools), crampons, and a small alpine rack.

We ascended the talus field to the moraine, where we gained the glacier. A pleasant walk up the tongue of the 30-degree glacier led into the cirque proper. By 11 a.m. we had easily passed the

bergschrund, and Wojtek led off on the first of three pitches up the ever-steepening glacier ice (up to 65 degrees). Using both ice and rock protection, and with stretches of simul-climbing, we covered 270 meters in only three pitches.

At the col, we first ventured up the south ridge, which we believed might continue to Mt. Sidney Dobson’s South Summit. I led 25 meters of lichen-covered grade 5.4 to gain a knife-edge ridge. The ridge offered 100 meters of fun au cheval maneuvers, short downclimbs, and stretches of dirty mossy sidewalk. We had hoped to follow this ridge another half kilometer to gain the southwest ridge of Mt.

24 MAZAMAS

Sidney Dobson, but unfortunately, the ridge ended and further climbing appeared committing and loose. We built a cairn on a high point along the ridge at approximately 2,419 meters (7,936 feet), had a late lunch, and rappelled back into the col.

We then started up the higher peak which flanked the left side of the couloir, simul-climbing broken terrain up the northwest gully. The climbing here was less exposed, but more strenuous and loose, with difficulties up to 5.7. One hundred meters later we reached a broad prominent summit at 2,435 meters (7,989 feet) with a beautiful view extending out to the Vampire Peaks and Cirque of the Unclimbables. To our surprise, the east face (which was not visible from the cirque below) was a steep talus field. Evidence of goat poop encouraged us down through ever looser and steepening talus. Back on the glacier, we decided that six v-threads would have been a better option.

We named our route Twisting Couloir (AD, 340 meters, AI3, 5.7). This fun, moderate climb (ten hours camp to camp) would be an instant classic if located closer to a major roadway, instead of a chopper ride from the end of the road at a defunct tungsten mine.

During our climb, Nick and Katie had been exploring the granite peaks lower in the valley for free climbing potential. After waiting out bad weather, they made their attempt on the Chair. Unfortunately, they were forced to turn back after 800 feet of climbing up to 5.11, due to inadequate

protection and un-freeable dirt and vegetation.

After a brief half-rest day, Nick and Katie then set their sights on “The Sentinel,” a commanding tower that guarded the entrance to the valley below. Their efforts were again unsuccessful. Although the tower appeared to have possible lines from afar, from the base it was clear that all of the potential cracks were again filled with dirt and vegetation. After circumnavigating the tower in search of a line, they returned to base camp

continued on next page

MAY/JUNE 2023 25

Ragged Range, continued from previous page

2023 BOB WILSON GRANT* RECIPIENTS: NAHANNI EXPLORATION

■ Grant amount: $12,000

■ Team: Angie Brown, Leader; Kyle Tarry, Damon Greenshields, and Sam Befell

■ July or August 2023

■ Summary: This expedition will spend fifteen days in the Nahanni National Park in the Northwest Territories of Canada exploring the Cirque of the Unclimbables. While in country, they primary objective will be an attempt to make the first long ridge traverse from Proboscis to Sir James MacBrien mountain. The route will take them over the most famous formations in the area (Proboscis and Lotus) and end on the highest peak in the area, Sir James MacBrien. The team has identified two secondary traverse objectives should the weather rule out their primary objective. They have smaller, one day objective to climb the Lotus Flower Tower via the South Buttress, one of the 50 Classic Climbs in North America.

ARCTIC ODYSSEY

■ Grant amount: $10,000

■ Team: Steven Wagoner, Bob Breivogel, Shawn Thomas

■ Late July to late August 2023

empty-handed, having found only lichen, veg-filled cracks, and choss.

With the weather window diminishing and a major storm a couple of days out, Nick and Katie made one last attempt to gain a summit, opting for the imposing Mt. Doom—a craggy glaciated peak towering over our base camp at the top of the valley. Despite their efforts, they were once again forced to turn back, this time due to excessively loose rock, characterizing the mountain as “literally a pile of stacked dinner plate choss.”

As they descended the flank of Mt. Doom, they decided to make a last-ditch attempt at a nearby summit (61.9702, -127.5893), following the ridge between the adjacent peaks. After their string of failures, fortune turned and Nick was able to scramble to the summit at 2,201 meters (7,223 feet), dubbing the line Consolation Prize (180 meters, 5.4).

With a winter storm approaching, and forecasts of up to 36 inches of snowfall, we decided to end our trip a few days early rather than spend the rest of it in our tents.

Looking back, the Ragged Range still offers much to be explored. Mt. Sidney Dobson (both north and south summits) remains unclimbed. Although the rock climbing was a far cry from what we were hoping, an earlier spring expedition might offer stellar ice and mixed conditions up these prominent peaks, bypassing much of the loose rock, discontinuous cracks, and wet weather that we encountered.

Editor's note: Due to delays in publishing this article, photo captions and citations were unavailable. Our efforts to contact the author were unsuccessful. If contact is made, and captions and citations are provided, we'll run a correction in a future issue of the Mazama Bulletin

■ Summary: This 15-day expedition will explore the valleys, ridges, peaks, and rivers of the Arrigetch Peaks deep within the Gate of the Arctic National Park, the second largest and least visited of all of the 63 National Parks. From base camps in the Arrigetch Valley, the expedition will attempt a climb of the North Ridge of Ariel Peak (6,685 feet) and the Elephants Tooth (4,805 feet). After climbing and exploring the Arrigetch, the expedition will float 20 miles down the wild and scenic Alatna Rive to Takahula Lake, where they will be picked up by float plane. Midway through the river float, the expedition will attempt to climb an unnamed (and potentially unclimbed) 3,480 foot granite peak that rises above Takahula Lake.

NORTH BAIRD CASE CAMP 2023

■ Grant amount: $3,000

■ Team: Zach Clanton, James Gustafson

■ August 2023

■ Summary: Zach Clanton and James Gustafson will attempt a pure rock climb of extraordinary proportions on an unnamed 2,150 meter peak (known informally as Desdemona Spire) within the great Sticking Icecap of Southeast Alaska. While this won’t be a first ascent, that was done as a largely glacial route with a couple of technical pitches in 1975, it will likely be only the second time the peak has been climbed and the first via the planned route. The intended route was first identified by Fred Beckey in 1946 and researched extensively by Zach in 2022. This expedition is also partially funded by an American Alpine Club Cutting Edge Grant.