We are the Mountain People.

Where some see rock, we see lines. Where some see peaks, we see possibility. Where some see rain lashed ridgelines or impenetrable fog, we see an opportunity to challenge our skills.

MAZAMA BULLETIN

Volume 105

Number 5

September/October 2023

CONTENTS

FEATURES

Return of the Wolverine, p. 8

(Re)launching Evening Programs, p. 10

Climbing in the Shadow of Our Vanishing Glaciers, p. 16

The Roof of Costa Rica, p. 24

COLUMNS

Executive Director’s Message, p. 4

President’s Message, p. 5

Mazama Membership, p. 6

The Mazamas: For the Love of Mountains, p. 7

Mazama Values, p. 7

Steep Snow & Ice Update, p. 14

Mazama Classics, p. 14

Mazama Arts, p. 15

Successful Climbers, p. 28

Board of Directors Minutes, p. 30

Colophon, p. 31

IN THIS ISSUE

Perhaps it seems counterintuitive, but to me, opening our membership in many ways realigned us with the original spirit of our founders, who clearly recognized the psychologically and socially empowering effects of the mountains..." p. 4

If a breeding pair of wolverines came to Oregon, could they maintain a population with continued habitat degradation?, p. 8

As my eyes then swept northwestward, down the furrowed, barren zone that was only recently a glacier-filled couloir, I gazed into the future of our mountains..." p. 16

Until we’re suddenly on it, hauling up over one final lip of rock to find that everything—everything in sight—and in Costa Rica, for that matter—is now below us..." p. 24

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE

by Rebekah Phillips, Mazama Executive Director

Over these last two months

I’ve had the privilege of meeting so many Mazamas, including the newest, still “adventure-curious” as well as an impressive number of seasoned climbers pushing five or more decades of membership. I’ve spoken to activity leaders, committee chairs, students, current and former staff, members of affinity groups, and volunteers who give more hours than a part-time job. As I get to know the people who make the Mazamas tick, I’ve sought to understand from your perspective: What makes this place so special? What keeps you coming back? And though I still have hundreds of conversations ahead of me, there’s one word that consistently rises to the top: community.

It's hardly surprising that an organization of nearly 130 years would boast such strong social ties. Indeed, some might argue that for most of its existence, the Mazamas ostensibly functioned as nothing more than a social club. But there’s no denying that our founders understood the power of connectedness, using their expertise and influence to pass legislation, secure public land protections, support research initiatives, and more. It wasn’t philanthropy so much as stewardship, generating and securing opportunities for the public to engage with a well preserved and thriving wilderness. Internally, the Mazamas built community by operating democratically, providing centralized gathering spaces, working within local, regional, and national alliances, and offering myriad leadership opportunities.

Perhaps it seems counter-intuitive, but to me, opening our membership in many ways realigned us with the original spirit of our founders, who clearly recognized the psychologically and socially empowering effects of the mountains. As the Mazamas evolves and we shift from providing niceties (services only a few have the privilege to enjoy) to necessities (services with a positive effect on society as a whole), the definition of “community” takes on new depth that warrants conversation, particularly now as we embark on the next year’s budgeting process and a broader strategic plan.

Though its current iteration is fairly new, what drives our commitment to community is our mission statement: to inspire everyone to love and protect the mountains. More than a legally required summary of our aspirations and ethos, our mission helps us organize our day-to-day operations and provides an important decision-making framework. In planning for the future, both tactical and strategic business decisions (yes, non-profits are businesses!) must be weighed with consideration to mission alignment. Just a few of the more pressing questions on my mind these days include:

■ How might we adapt or augment our offerings to better serve and recognize the varying needs of a diverse membership?

■ What resources are required to support a growing and engaged membership? At what rate must we grow resources to meet demand over time?

■ Are we investing in partnerships and collaborations to maximize reach and impact?

■ How are we soliciting and responding to both internal and external feedback?

■ How can we strengthen our financial position year over year?

I’m excited to explore the opportunities and responsibilities that come with building the Mazamas of tomorrow. With membership dues covering less than 20 percent of expenses, it made good

business sense to increase access, but it also just makes sense from a humanitarian perspective. After all, whether you consider the Mazamas a school, a society, a safety net, or a gathering space, what unites us is not some singular goal to scale and summit a peak. Rather, like our founders, it is a shared respect for the many ways in which the mountains bring us together: discovery, grounding, healing. We can all use more of that.

To our community today, I thank you for your partnership and guidance in walking this path together. I hope you’ll join me in welcoming warmly our community of the future as we learn what it means to inspire everyone to love and protect the mountains.

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

by Greg Scott, Mazama President

When I ask members what value proposition does the Mazamas bring, the most common answer is community.

Since the last bulletin I was fortunate enough to experience three examples of how the Mazama community comes together and supports each other.

First, I went to the Classics Picnic at Dick and Jane Miller’s house on July 4. It was great to see this event return and to see everyone catch up. The common thread of every story I heard was that each individual was influenced by another. Generations of leaders have left their mark on the Mazamas. I felt a sense of belonging being able to speak their language and share my own stories about who mentored me and who I’ve been fortunate enough to say I mentored. Next, I marched in the Pride Parade as an ally with the Queerzamas. While waiting for the parade to start a former Mazama Board member happened to be at the event and let me know how excited she was to see the Mazamas

participating in this parade. Marching in the parade it struck me how many attendees had heard of the Mazamas. At the end of the parade a man came up to us and shared that his husband had been a Mazama and climber for decades and had a collection of artifacts and photographs we might be interested in seeing. Finally, I attended Tom Guyot’s ramble retirement party at the Lucky Lab last week. Wendy Guyot, Tom’s daughter, and I took BCEP together in 2002 and the Guyot’s have been family friends ever since. One of my former students, Hannah Raynor, baked a cake featuring Forest Park and REI for Tom, and magically fed the dozens of people who attended. All three of these experiences

reinforced my belief that community is at the center of the Mazama experience. We each find and nurture our communities within the Mazamas. With the Route Ahead in its final stage, developing a new strategic vision, I’m reminded that like a climb this is the most difficult stage and takes team work. We will all need to kick steps, place protection, and trust one another to reach the summit.

MAZAMA MEMBERSHIP

JUNE Membership Report

NEW MEMBERS: 33

Ethan Adelman-Sil

Amelia Alonso

Wyatt Baldwin

Anna Borroz

Chris Bowman

Mark Creevey

Carter Eck

Ian Edgar

Trent Erb

Tammy Erb

Julie Gursha

Nikola Hamilton

Jessica Herrington

Matthew Hoyer

Jiamu Hu

Craig Koon

Stephen Krenkel

REINSTATEMENTS: 2

DECEASED: 1

MEMBERSHIP ON JUNE 30:

2,477 (2022); 2,950 (2023)

Alex Krolick

Haki Lee

Steve Long

Patricia Nardone

Christine Olinghouse

Matthew Palmer

Spencer Parsons

Diane Peters

Dustin Putt

Beverly Roxby

Yasmin Sahul

Doug Sandburg

Justin Sovich

Phil Stanfill

Shawna Vickers

John Yates

Whether you are new to the Northwest, a seasoned backcountry traveler, a longtime Portland resident who’s ready to start exploring, or somewhere in between, we can connect you to the hiking, climbing, and skiing adventures you seek.

■ Climb a mountain

■ Go rock climbing

■ Hike or backpack

■ Backcountry ski or snowshoe

■ Discover canyoneering

JULY Membership Report

NEW MEMBERS: 12

Lily Barchers

Marine Barthelemy

Matt Cordes

Ryan Curren

Julia Curren

Sumathi Devarajan

REINSTATEMENTS: 2

DECEASED: 1

MEMBERSHIP ON JULY 31:

2,762 (2022); 2,961 (2023)

Brian Keefe

Kent Klein

Catherine McDonald

Lisa Spahr

John Stockmann

Kelly Turner

■ Meet interesting people

■ Learn new outdoor skills

■ Check out our library

■ Stay at our mountain lodge

■ See a presentation

■ Discover new places

■ Trek in a foreign country

■ Join an outing or expedition

■ Fix a trail

■ ... and so much more!

Editor's note: Due to the elimination of the glaciated peak membership requirement, we will no longer be publishing the names of qualifying peaks with new members.

THE MAZAMAS: FOR THE LOVE OF MOUNTAINS

MAZAMA VALUES

SAFETY

We believe safety is our primary responsibility in all education and outdoor activities. Training, risk management, and incident reporting are critical supporting elements.

EDUCATION

We believe training, experience, and skills development are fundamental to preparedness, enjoyment, and safety in the mountains. Studying, seeking, and sharing knowledge leads to an increased understanding of mountain environments.

VOLUNTEERISM

We believe volunteers are the driving force in everything we do. Teamwork, collaboration, and generosity of spirit are the essence of who we are.

COMMUNITY

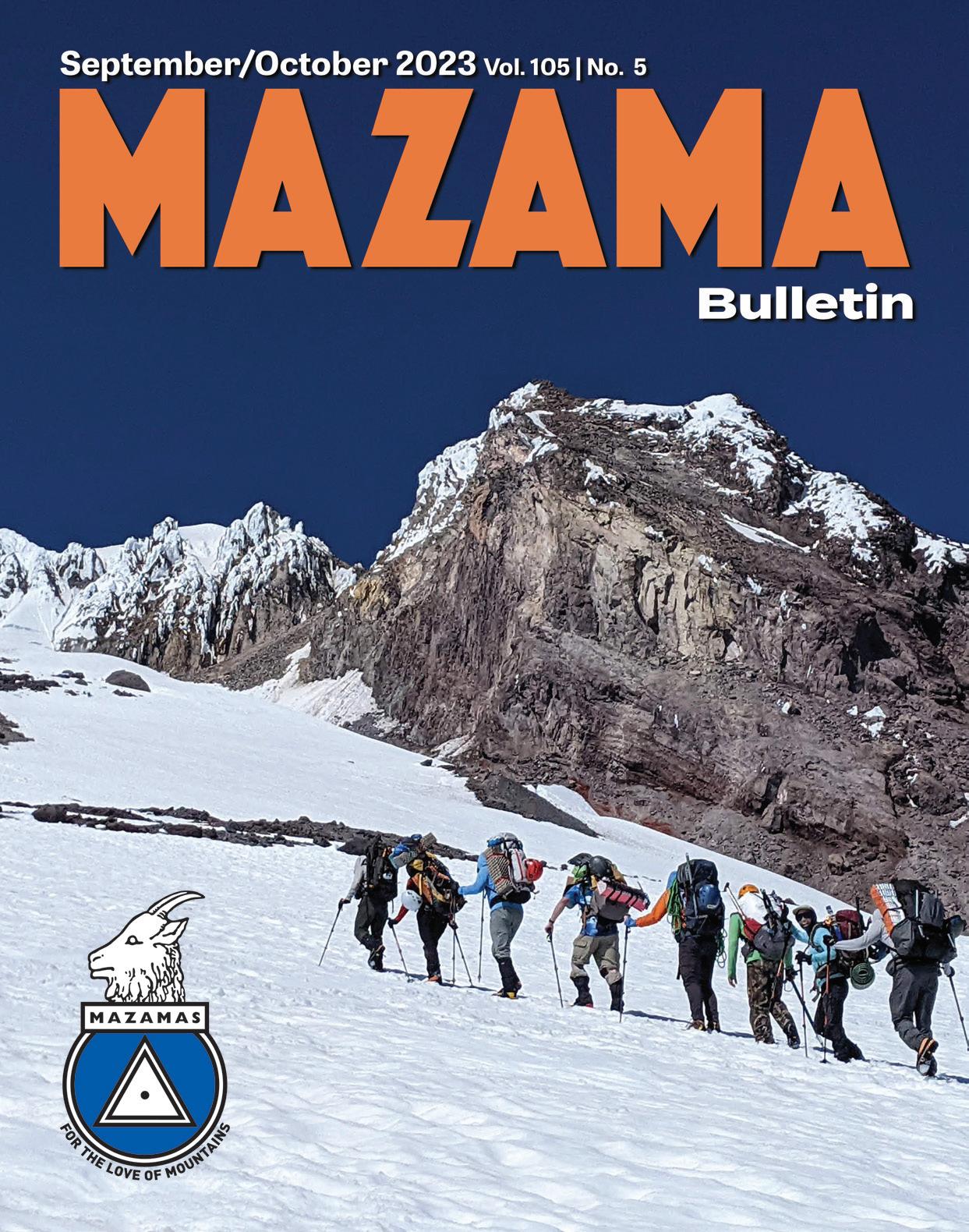

The Mazamas: For the Love of Mountains is an upcoming exhibition in the Hayes Gallery at the Oregon Historical Society. The exhibit traces the impressive 129-year journey of the Mazamas, an organization rooted in the Pacific Northwest. Guided by the curatorship of Mathew Brock, the Mazama Library and Historical Collections Manager, alongside Allison Ackerman, the Adrienne C. Nelson High School Librarian, this exhibit draws its essence from the Mazama Library and Historical Collections' holdings.

A diverse array of rarely glimpsed artifacts, photographs, and records will take center stage, crafting an immersive odyssey through the Mazamas past and its dynamic trajectory into the future. This trajectory is marked by an unwavering commitment to nurturing responsible outdoor recreation, forging pathways for education, and fostering a robust sense of community across the region.

From its humble beginnings atop Mt. Hood, the organization has flourished to encompass a spectrum of outdoor pursuits extending beyond mountaineering, spanning from hiking and canyoneering to rock climbing and skiing. Complementing these ventures, the Mazamas have played a pivotal role as stewards of conservation and funders of scientific research.

At the heart of the Mazama ethos lies an unwavering dedication to community—a thread interwoven into every facet of its identity and the propelling force behind its ongoing evolution. As you delve into the history of the Mazamas, you'll discover how the organization is shaping a more inclusive and accessible tomorrow, forging deeper connections between Oregonians and their love for mountains.

Mark your calendars, for this exhibit will open on Friday, November 10, 2023, and run until March 24, 2024.

We believe camaraderie, friendship, and fun are integral to everything we do. We welcome the participation of all people and collaborate with those who share our goals.

COMPETENCE

We believe all leaders, committee members, staff, volunteers, and participants should possess the knowledge, skills, abilities, and judgment required of their roles.

CREDIBILITY

We believe we are trusted by the community in mountaineering matters. We are relied upon for information based on best practices and experience.

STEWARDSHIP

We believe in conserving the mountain environment. We protect our history and archives, and sustain a healthy organization.

RESPECT

We believe in the inherent value of our fellow Mazamas, of our volunteers, and of members of the community. An open, trusting, and inclusive environment is essential to promoting our mission and values.

RETURN OF THE WOLVERINE

by Jen TraversWhen a wolverine was photographed this spring on the Columbia River bank near Troutdale, we, the volunteers of Cascadia Wild rejoiced. We’ve been anticipating the wolverine’s return to Oregon for years.

Historically, wolverines were known to inhabit the Oregon Cascades. Through trapping in the 1800s, followed by habitat loss, they began to disappear and were considered extirpated by the 1930s. Until this year, the last wolverine confirmed in western Oregon was a 2 year old male that was struck by a car on I-84 in 1990.

Wolverines are mostly scavengers, and have a home range of up to 400 square miles. They can live in a wide variety of terrain, but have specific habitat requirements for reproduction. A deep snowpack well into May is needed for denning. Mt. Hood, Mt. Jefferson, and the Sisters (which now have vast surrounding

protected wilderness areas) are the ideal terrain for a wolverine family.

At least one other wolverine has been confirmed in the Wallowas, where the high elevation persistent snowpack provides good habitat. In 2019–2020, Wallowa researchers deployed 14 motion controlled cameras, and were only able to detect (many shots of) a wolverine named Stormy, who has been a resident since at least 2011. There has been no evidence of any reproduction or other individuals in the area.

As sad as that lonely bachelor story is, we have good news closer to home. Wolverine populations are increasing in Mt. Rainier National Park. Remote cameras

have shown the emergence of successful litters in the past three years! It is likely that one of these youngsters decided to head south and swim across the Columbia to become an Oregonian.

So, where did they go after crossing the Columbia? We know a few things. One was spotted a few days later in Colton, by a motion sensor wildlife camera, and observed by a driver in Damascus, who filmed it loping across a field.

Then, in early April, another driver near Santiam Pass saw something trying to cross the road. He was able to get good video footage of a wolverine waiting for a break in traffic and then bolting across the highway.

It’s not clear, but highly likely that this was the same individual on the Columbia. Did the wandering wolverine bypass Mt. Hood? Initially it seemed so. In late April, however, Cascadia Wild was consulted by a climber about possible wolverine tracks observed over 10,000 feet on Mt Hood. The tracks were distinctly of the mustelid family. The only other animal that could have made these tracks is the Pacific marten, which is usually a forest resident. The main distinguishing feature between these two animal’s tracks is the size. Wolverine tracks are typically 3.5–5.5 inches wide, and marten are 1.5–3 inches wide. Unfortunately, no size reference was taken for this photograph.

With the Wilderness Act and environmental regulations, the wolverine now has increased area for expansion and re-establishment in its historical range. At odds with this vast available territory is the decrease in winter snowpack of our alpine region due to climate change. If a breeding pair of wolverines came to Oregon, could they maintain a population with continued habitat degradation?

We at Cascadia Wild are continuing to monitor remote motion-sensored cameras throughout the Mt. Hood National Forest. Although we have not caught a glimpse of the wolverine on our cameras yet, we are now more optimistic it will happen. In the meantime, we will continue to collect

data and observations of the many animals on our mountain, learning more about their habits. We’ve seen elk, bear, cougar, marten, marmot, coyote, deer, bobcat, and the grey wolf visiting our sites. Countless chipmunks, rabbits, and squirrels perform for the cameras. We’ve seen glimpses of the flying squirrel and the occasional mink. We’ve learned that there is a healthy population of Sierra Nevada red fox living in the alpine areas of the mountain.

If you’d like to join a camera crew or go on a tracking trip, check out our website to sign up: www.cascadiawild.org.

(RE)LAUNCHING WEDNESDAY EVENING PROGRAMS

by the Mazama Base Camp Committee

This fall, in an effort to further expand its reach and tap into the ever-growing community of outdoor enthusiasts, the Mazamas is resurrecting its popular, often standing-room-only evening programing, and renaming it Mazamas’ Base Camp.

Free and open to the public, Mazamas’ Base Camp programming will run from October to May. Base Camp presents an exceptional opportunity to explore and understand the natural wonders of the Pacific Northwest. Through discussions, the series aims to enhance participants' knowledge and appreciation for the region’s diverse ecosystems—from the destructive force of wildfires to the serene majesty of glaciers to the intricate world of trailside plants. Armed with newfound knowledge and greater respect for the environment, we hope attendees will be inspired to become responsible stewards of these precious landscapes, ensuring that future generations can also revel in nature’s enchanting beauty.

As climbers and conservationists, the Mazamas hold a deep admiration for glaciers, the ancient rivers of ice that have shaped much of our region’s rugged terrain. In the evening program on glaciers, participants will embark on a fascinating journey through time, understanding the origin and dynamics of these majestic ice formations. Representatives of the Oregon Glaciers Institute will lead a discussion on climate change impacts, glacier recession and the significance of preserving these ice giants for future generations. Through an immersive presentation and captivating visuals, attendees will deepen their knowledge of glaciers and better understand their role in maintaining a delicate ecological balance.

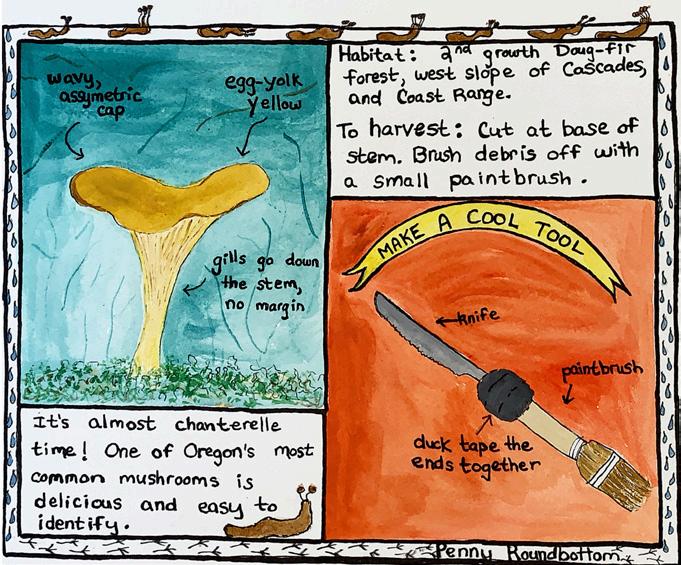

As glaciers advance and retreat over time, they have a significant impact on the landscape, creating various habitats that support different plant species. We have a couple of Base Camp offerings to address our region’s botanical wonderland, adorned with an astonishing array of trailside plants and fungi. Co-founders of the Arctos School of Herbal and Botanical studies will unveil for Base Camp attendees a few secrets of native species and their ecological roles. They will share their expertise identifying different plant species and explaining their uses in traditional medicine and local ecosystems. The goal is for Base Camp attendees to emerge with a newfound appreciation for the intricate web of life that thrives on the trails they traverse.

The hope is that more people will apply and share this knowledge when they spend time in nature. The Mazamas legacy is deeply rooted in hiking and mountaineering, making our evening programs centering on trails a integral part of the Base Camp offerings. A few seasoned hikers, guidebook authors, including longtime Mazamas Matt Reeder and William L. Sullivan, and trail experts will share their favorite treks, providing invaluable tips on trip planning, safety precautions, the 10 essentials and Leave No Trace principles. To discuss how we manage public lands in a way that embraces the human-powered experience, the Outdoor Alliance (OA) presentation will help Base Campers understand the issues, how to talk effectively about them, who to talk to, and when it’s most effective to do so. One of OA’s most significant research efforts to date includes a report on wildfires and how recreationists can support a fire-resilient future.

In the Pacific Northwest, wildfires have become increasingly prevalent and pose a significant threat to both the environment and communities. The Mazama evening program on wildfires delves into the complex dynamics of these devastating phenomena. Experts in fire ecology and wildfire management lead the discussion, providing valuable insights in the science of wildfires, their causes and their implications on forest ecosystems.

As the Mazamas continue to embrace the power of outdoor education and exploration, they hope to ignite a passion for nature that ripples through our members and beyond. By attending these evening programs, participants can become part of a collective endeavor to safeguard the natural wonders of the Pacific Northwest. We hope to see you at one, two, or all of our Base Camp programs. Tell your friends and neighbors! Additionally, we are seeking sponsorships. If you work for or own a business that might be a good fit, let us know—programs@mazamas.org—and we’ll reach out to them.

FALL 2023 BASE CAMP PROGRAMS

OUR CHANGING GLACIERS

Oregon Glacier Institute

Oct. 4, 2023

Join us for a night all about glaciers. From Oregon's top climate scientists, spend an evening learning about how glaciers respond and change to shifts in the climate and what this means for our recreational spaces and mountains. To stand on a glacier is to stand on history, and to stand on what possibly could become a relic of the past. Help preserve our wild spaces by learning about these magnificent glaciers and spreading awareness in our community and beyond.

FABULOUS FUNGI & OTHER FALL TRAIL DELIGHTS

The Arctos School of Herbal and Botanical Studies

Oct. 18, 2023

Ever wonder what kind of fungi you pass on the trail? Or perhaps which ones are edible? The Arctos School presents a night of learning about what might grow trailside as you explore our fruitful environment.

PEAK RECOVERY + MAZAMA AFFINITY GROUPS

with Ali Marie Koch & Brent Canode

Nov. 1, 2023

Anyone who has taken time to recharge, reset, or release in nature knows just how truly healing it can be. Learn about a community group that is making sure our wild spaces are accessible to those in recovery.

DOCUMENTARY FILM NIGHT:

Bandaloop, Arctic Games of the North, & Ski Mountaineering

Dec. 6, 2023

Movie night! Bring blankets, pillows, and popcorn as we present a night of films. Our first feature is all about the culture and games of indigenous peoples in the arctic. The second feature showcases ski mountaineering around the world and in our backyard. Snuggle up and settle in for a snowy night to learn and get excited about getting outside in the winter.

continued on next page

WINTER 2024 BASE CAMP PROGRAMS

ADVOCACY IN THE OUTDOORS

Outdoor Alliance

Jan. 17, 2024

Outdoor Alliance is the only organization in the U.S. that unites the voices of outdoor enthusiasts to conserve public lands. They help ensure those lands are managed in a way that embraces the human-powered experience. Outdoor Alliance knows the landscape of conservation policy and politics. They understand the issues, how to talk effectively about them, who to talk to, and when it’s most effective to do so. Most importantly, Outdoor Alliance empowers people with critical information, helping them understand how they can make a difference.

THE MAGIC OF TRAILSIDE PLANTS

The Arctos School

Feb. 7, 2024

The Acrtos School is back. To complete their series and expand your knowledge of the foliage and flora that call the Pacific Northwest home, we will be learning all about springtime plants. Bring your curiosity and notebooks to help you identify trailside plants as you wander through the wilds this spring and into summer.

BACKCOUNTRY FILM FESTIVAL

Winter Wildlands Alliance

Feb. 21, 2024

Backcountry Film Festival manifests the power of humans and their spirit. It screens cinematic stories of outdoor stewardship, grassroots policy and advocacy work, backcountry adventure, and snow cinema by human-powered advocates, athletes, brands, activists, adventures, and outdoor enthusiasts.

MAZAMA BOB WILSON EXPEDITION GRANT RECIPIENTS

Steven Wagoner, Bob Breivogel, and Shawn Thomas

March 6, 2024

The Mazama Bob Wilson Expedition Grant recipients describe their travels and climbs in Nahanni National Park in the Northwest Territories of Canada. Their explorations include the Cirque of the Unclimbables, the Gates of the Arctic National Park, and a pure rock climb on an unnamed 2,150-meter peak within the great Stikine Icecap of Southeast Alaska.

SPRING 2024 BASE CAMP PROGRAMS

EXTRAORDINAY OREGON & HIKING BASICS

Matt Reeder & the Adventurous Young Mazamas

April 3, 2024

Everyone belongs in the outdoors and wild spaces, but where do you start? What gear is essential? Where should you go? Mazama member Matt Reeder will present on his latest guidebook, Extraordinay Oregon!, which seeks to demystify and introduce our trails. The Adventurous Young Mazamas will, in true Base Camp style, take it back to the basics to ensure anyone who wants to can recreate safely in our backyard.

HIKING THE PCT & MENTAL HEALTH; PACIFIC CREST TRAIL GEOLOGY

Kyra Miller & Peter Laciano

April 17, 2023

Ever wonder how our volcanoes came to be? Who put that rock there? Always wanted to hike the PCT? We are bringing in two special guests to answer all of your questions regarding rocks and hiking. Kyra Miller is an outdoor enthusiast who spent half of 2022 taking a journey on the PCT to heal her mental health. Peter Laciano is a geologist by training and is currently doing field work with the USDA regarding snow pack and water supply in the PNW.

NEW HIKES IN OREGON

William Sullivan

May 1, 2024

As the sun starts to peek out and rain clears away we have the perfect host to get you excited to try some new, recently built trails. Bill Sullivan introduces his guidebook on some New Trails in Oregon. Perhaps you'll be the first to walk on them.

REIMAGINING WILDFIRES SCREENING & EXPERT PANEL

Elemental

May 15, 2024

Summers have gotten hotter and smokier. Join us for a night learning about wildfires. We will watch a movie to help introduce and educate us about wildfires, followed by a chat with a professor who is an expert on these dangerous events.

STEEP SNOW & ICE UPDATE

by Ed Dyer, SSICommittee chair

Steep Snow & Ice (SSI) has entered its third year and continues to grow. This year we were able to recruit four new instructors: Darren Ferris, Kirsten Isakson, Petra Le Baron, and Scott Branscum. We are especially excited as both Petra and Scott are members of Portland Mountain Rescue and bring with them new rope tricks and skills. We remain a small committed team as we also lost a few instructors: some even moved to Bozeman to have more access to ice climbing!

We had more than 40 applicants for the August SSI skillbuilder's 12–14 student acceptances. Not only was this the most applicants ever to SSI (clearly there is growing enthusiasm) but it was the strongest and most experienced group of interested climbers to date. The August SSI skill-builder is starting even as I write this update so look for a debrief and photos in the next bulletin.

MAZAMA CLASSICS

For members with 25 years of membership, or for those who prefer to travel at a more leisurely pace.

We lead a wide variety of year-round activities including hikes, picnics, and cultural excursions. Share years of happy Mazama memories with our group. All ages are welcome to join the fun.

CONTACTING THE CLASSICS

Contact the Classics Chair, Gordon Fulks at classics@mazamas.org.

SUPPORT THE CLASSICS

The Classics Committee needs a volunteer to put more content in our column on a quarterly basis. We want to document past Classics events and make sure that our postings to the web are current and complete. More generally, there is always work to be done on the committee. Our meetings are the fourth Monday of every other month at 11 a.m. on Zoom. Email classics@mazamas.org and tell us how you can help.

CLASSICS COMMITTEE MEETING

Keep an eye on the Mazama calendar for our next meeting.

MAZAMA MERCHANDISE ON SALE NOW!

MAZAMA ARTS

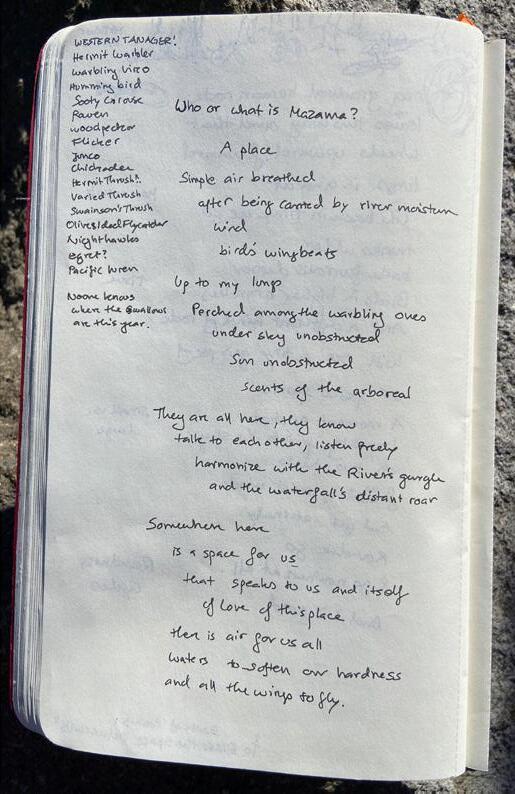

Anna S, who scouted the Mazama Trail ahead of the July work party, and then joined to help with trailwork, wrote this poem. Along with the poem, she has also included a list of birds heard in camp.

REQUEST FOR BULLETIN SUBMISSIONS

Alex

Honnold may be able to do it solo, but we can’t!

You are the Mazamas. Your stories, your adventures, and your knowledge define the organization. The Bulletin should represent that. With your help, we can produce a better product for you. The Publications team is a talented group of writers, editors, and you-can-do-it! cheerleaders willing to help you transform your knowledge and narratives into feature content to be shared with your fellow Mazamas. What will we publish? Just about anything of interest to the organization: tips and tricks, stories of trips taken, reporting on Mazama events, profiles of people, poetry, news from the climbing world, and on and on.

There are two ways that you can get your ideas into print. The first is to tip off our crack team of writers about your idea and let us do all the heavy lifting. The second is to share with us a draft of your contribution, and we can help polish it up. Our staff includes experienced editors capable of working with you to craft top-notch writing.

Pitch us your ideas by emailing publications@mazamas.org

CLIMBING IN THE SHADOW OF OUR VANISH ING GLACIERS

by Peter BoagFully alone at 9 a.m. on October 2, 2022, I stood for my first time on the 8,750-foot summit of Diamond Peak, an isolated massif composed of meandering alpine ridges that straddle Oregon’s south-central Cascade Range. I saw something there that I was unprepared for: a large patch of glare ice beneath thinning snow—the last trifling remnants of what the Mazamas had once called Diamond Glacier. Staring at that vestigial ice yet clinging to the highest point of a shade-providing cirque just west of the summit, I looked into the past, where my thoughts and memories freely wandered. As my eyes then swept northwestward, down the furrowed, barren zone that was only recently a glacier-filled couloir, I gazed into the future of our mountains.

This bittersweet moment came after the end of a climbing season with the Mazamas during which I had sauntered over and around many now ice-free places that earlier in my very lifetime supported glaciers. I had ambled through the broad valley once occupied by the expansive White Chuck Glacier, just south of Glacier Peak. I had peeked over the edge of the North Sister and into the abyss from which

Thayer Glacier had recently vanished. From one of the rocky ridges that compose Three Fingered Jack, I also warily glanced down into the deep gouge that an improbably low-elevation glacier named “Jack,” now a memory, had created. And on Mt. Jefferson, in the dark hours of an early August morning, I quietly passed by a snowfield that was not long-ago Timberline Glacier.

At the end of this season, I set out on two climbing expeditions of my own. Lovely weather continued into the first days of autumn, and I planned to climb some lesser Oregon peaks that I long wished to summit. Both these adventures also led me into areas that had historically and recently supported glaciers. The second of these trips was the one that brought me up Diamond Peak and face-to-face with

the unanticipated remnants of a past that was fast melting away. I first learned of the evanescent Diamond Glacier a half-century earlier and only a couple years after a 1970 camping trip to Central Oregon, where the variety of snow-clad mountains one can witness there sparked my interest in the Cascades. Afterwards, I pored over all recently and historically printed national forest, wilderness, and topographic maps that I could lay my hands on. I memorized the mountains’ elevations, which I can still rattle off, though many subsequent geographic surveys have revised these figures that still populate my mind. And I read whatever I could about the geology, history, and lore of our great volcanoes.

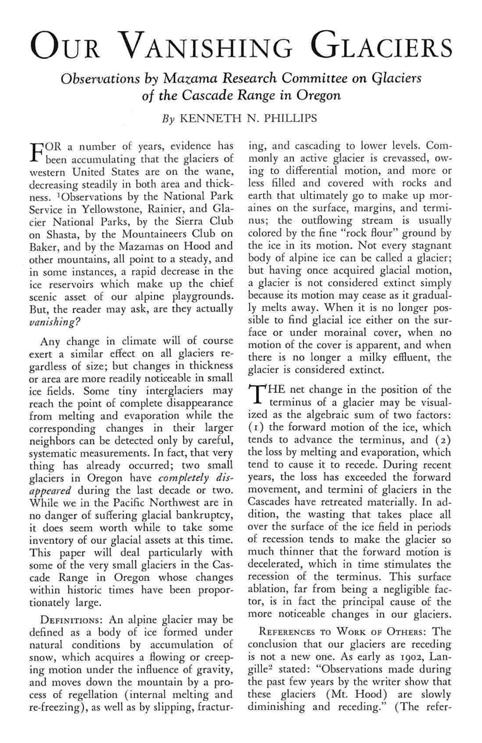

Much of my investigation I conducted in Portland’s Central Library and its then wondrous Map Room. One Saturday morning there in 1973 or ‘74, a librarian brought to me “Our Vanishing Glaciers,” an article that Kenneth N. Phillips, a civil engineer with the United States Geological Service and chair of the Mazama Research Committee, wrote in 1938 for our annual. In addition to some glaciers that I had knowledge of, Phillips also told of three that neither textual source nor the most detailed map had ever divulged to me: Jack Glacier on Three Fingered Jack, Dutchman Glacier on what we then called Bachelor

Above: When I came across Kenneth N. Phillips’s “Our Vanishing Glaciers” (1938) in the early 1970s, it sparked my emerging interest in all things related to Diamond Peak.

Butte, and, of course, Diamond Glacier on Diamond Peak. To be sure, national forest maps from that era did indicate permanent snow or ice fields on Three Fingered Jack and even Mt. Washington, but those bodies went unnamed. Similarly, the Bachelor Butte topographic quadrangle from 1963 plainly shows an ice body where Phillips located Dutchman Glacier, though it was also unidentified. Absolutely no source

continued on next page

Vanishing Glaciers, continued from previous page

before Phillips had indicated an ice body or permanent snowfield on Diamond Peak. “A glacier of this type,” Phillips explained, “could easily be taken for an ordinary snowfield, even by experienced mappers or geologists, if seen at any time except in the latter part of a dry, warm summer. The nearby ridges protect the snow against melting so well that the glare ice, crevasses, and other positive signs of glacial character may not appear until late in the season.” Phillips’s prose deepened for me the mystery of that relatively isolated jumble of high ridges and helped to transform this mountain into one of my favorite Cascade peaks.

On September 24th, just the weekend prior to my ascent of Diamond Peak, I headed out on the first of my two fall 2022 trips to climb lesser summits in the Oregon Cascades. Considering the ease of the routes that I planned, I took along my then three-year-old dog, Oliver, for companionship. Although on paper Ollie is a miniature Schnauzer, in truth his near 30 pounds places him less in the category

of “show quality” and more in the class of sturdy hiking partner. He had been training with me for climbing that summer. Over that time, he also listened to me read aloud to my husband Tom Ryan’s memoir Following Atticus. In it, Ryan tells the heartwarming story of how he and his mere 20-pound Schnauzer, Atticus, had nearly made it twice one winter to the summits of all 48 of the 4,000-foot peaks that compose New Hampshire’s White Mountains.

So, Ollie was fully ready to climb a mountain—or three, as it turned out. On the morning of Saturday, September 24, we headed to Mt. Bachelor Ski area’s West Village parking lot. There, just before 8 a.m. we shut the car doors behind us and made our way to the Mt. Bachelor trail that we then followed quietly upward about 2,700 feet to the peak’s 9,068-foot summit.

We were happily, though only briefly, by ourselves there. Through the morning, I took in the stunning views, which included Broken Top to the north. According to the Oregon Glaciers Institute, that ancient volcano had lost two glacial bodies in the last few years. There is confusion over the names of Broken Top’s glaciers since their designations have moved about on maps and in reports over the years. Some of the maps available in the early 1970s show Crook Glacier perched on the east side of Broken Top. Later, “Crook” migrated to an ice field on the south side of the mountain, which on earlier maps had no name.

Phillips, in his 1938 writings and photographs, used the name Crater Glacier to refer to that ice body. He placed Crook Glacier on the east side of Broken Top in compliance with maps of his era. His photograph of it shows it disarticulating into a moraine lake. In the summer of 1986, I hiked with a couple friends up to what I knew from Phillips’s report as Crook Glacier. In its moraine lake, I took the coldest dip that I ever remember—small icebergs floated there, icebergs that the then plainly visible glacier had calved. Today that ice body is no more.

On Bachelor, Ollie and I also looked down into Dutchman Glacier’s abandoned couloir. In 1938, Phillips wrote that he was able to find on August 17th of that year some 300 feet of “clean glare ice, not crevassed” yet remaining at the upper end of it. He also explained that accounts from the previous decade indicated that ice and snow had then extended all the way down to the terminal moraine, where Phillips now only found scree that likely covered no remaining ice at all. A report, undated in the Mazamas collections (though entitled “Mt. Bachelor,” which suggests that its authors created it after 1983 when that name replaced “Bachelor Butte”), mentions a “small glacier on north face just below summit.” When Ollie and I made our journey there years hence, only a few patches of snow hugged the western moraine where heavy wind loading occurs in winter. Sometime between 2015 and 2021, according to the Oregon Glaciers Institute, the last of Bachelor’s glacial ice had disappeared.

On another note, when I reached the top of Bachelor, I completed my ascent of the nine mountains in the Oregon Cascades that reach elevations above 9,000 feet. The first on that list had been 9,495foot Mt. McLoughlin, which I had reached

on October 8, 2014. Long before, on August 16, 1896, a group of Mazamas discovered a glacier lurking in one of McLoughlin’s north-facing cirques. Period reports explain that it had a 50- to 75-foot-deep crevasse. The climbers named the ice body in honor of one of their number, Charles H. Sholes, who was also our organization’s president at the time. McLoughlin’s last ice patch vanished sometime in the early 20th century. Kenneth Phillips wrote its eulogy, “Farewell to Sholes Glacier,” for the 1939 Mazama Annual. In it, he also asked, “Why are our glaciers receding?”

Receding, vanishing, shrinking, and disappearing are words that one finds in many Mazama reports on glaciers since

early in our history. Already in 1895, the year after our founding, the Mazama Annual reported on our first official expedition to explore glaciers—an excursion to compare the ice bodies of Mt. Adams and Mt. Hood. In 1903, the renowned glaciologist Harry Fielding Reid asked the Mazamas to begin collecting details on the Northwest’s glaciers to provide comparative data for studies then underway on the recession of glaciers in Europe. The Mazamas systematic consideration of the Cascades’ ice bodies did not commence, however, until after the Executive Council created the Research Committee in 1924 and charged it with collecting scientific knowledge about our snow-peaks. The next year, we began a decades-long survey of Eliot Glacier on Mt. Hood. Soon, reports on other glaciers in the Cascades began regularly appearing in our annuals just as the glaciers themselves began disappearing.

I thought about this history as Ollie and I descended Bachelor in the shadow of its now-vanished Dutchman Glacier and as we passed by varied buildings and under chairlifts. We arrived back at West Village a little after noon. By then one could see and hear the hubbub of lifts conveying bikers up the mountain who then rapidly tore down the flanks of what will always be to me Bachelor Butte. Back in 1986 when I was in graduate school in Eugene, two friends and I founded what was no more than a symbolic organization to protest the recent success of the Mt. Bachelor Ski Corporation in prodding the Oregon Geographic Names Board to transform Bachelor Butte into Mt. Bachelor—the latter a geographic designation apparently more desirable to ski on. I suggested BBLoC—pronounced block—for our organization’s name. It stood for Bachelor Butte Liberation

continued on next page

Corporation. Our mascot was a large, three-dimensional map of our beloved butte that I handmade. I blew up the topographic map of Bachelor on a photocopier, pieced together the many pages resulting from that, traced alternating topo-lines from them onto two sheets of quarter-inch thick foam core, carefully cut them out with an X-ACTO knife, and stacked and glued the alternating layers together. (I should have been working on my dissertation.) It hung in my homes for years. And now, many years since and on the morning of September 24, 2022, whereas Ollie and I may have climbed up and down what is officially a mountain, in my thoughts and memories we ascended and descended a Butte. I also imagined that our Butte wept away its glacier when it became in name and fact a commodity in the modern marketplace.

With Ollie sacked out in the back of our small SUV, we departed Bachelor and headed south to Diamond Lake. Despite

it being a Saturday, it was so late in the season that we had no problem finding a choice campsite at Thielsen View Campground. The next morning, at 6:50 and just as it was getting light, we appeared at the head of Mt. Bailey Tail #1451. At roughly ten miles out and back with an elevation gain of 3,200 feet, it is a bit more challenging than what we had encountered the previous day. But the going was great, and we were delightfully alone all the way to the summit and part way back down.

Among the few souls we met during our descent were Mazamas who the previous day had summited Mt. Thielsen on the opposite side of Diamond Lake.

Bailey has no glacier, but it has many ice-carved valleys radiating from its summit. Hikers can get an exceptionally interesting view of one of these through the natural hole in the ridge below and south of the summit. I watched in amusement as Ollie, who otherwise nonchalantly trotted through the more exposed parts of the

route, only tentatively inched toward that odd gap in the rocks to peer cautiously down into Bailey’s glacial past.

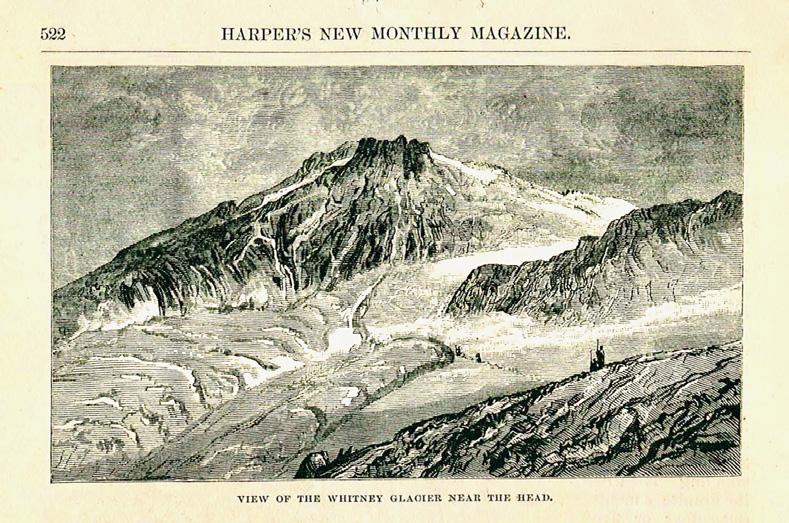

A few years ago, in one of our annuals, Martin Lafrenz, a Portland State University geologist, reported that Bailey likely did not even have a glacier during the Little Ice Age, the period of global cooling that began around the year 1300 and during which our alpine glaciers advanced. That colder era concluded just about when the Mazamas and its predecessor the Oregon Alpine Club formed in the 1880s and 1890s. It was only a decade or two before then when glaciers in the United States outside of Alaska were “discovered” and the news related to a broad audience. Significantly, this began in the Cascades. In 1869, the English artist Edward Coleman, known for his paintings of glaciers in the Alps, was the first to report on western glaciers and in this case those of Mt. Baker. His story appeared in the widely distributed Harper’s Monthly. For this piece, Coleman drew from his experience the previous year when he was a member of the first known group of climbers to reach Baker’s 10,786-foot

summit. Two years after Coleman’s climb, the geologist and surveyor Clarence King became credited as the first to scientifically discover a glacier in the American West. He did so on Mt. Shasta when he came upon and named Whitney Glacier.

There have been brief periods since that have witnessed the expansion, advance, and even formation of entirely new alpine glaciers in the Pacific Northwest. The best known in the latter category is Crater Glacier on Mount St. Helens that only appeared after that volcano’s catastrophic 1980 eruption. The overall trajectory for the Cascades’ glaciers since the Mazamas formed, however, has been recession. A recent report notes that since 1900, Mt. Rainier has lost more than 50 percent of its ice mass. It is also difficult to imagine for those of us familiar with Mt. Hood that in 1905 the Mazamas reported that the White River Glacier on the mountain’s south side extended 1.75 miles downward, terminating around 6,900 feet, and that as recently as 100 years prior, it likely stretched another two miles down its valley, to below where the Timberline Trail

now crosses the White River. Just in the last handful of years we have seen with our own eyes and repeatedly read in news releases the complete disappearance of some of our glaciers. Among the most recent are Pyramid, Stevens, and Van Trump on Rainier; Hinman in Washington’s Alpine Lakes Wilderness; Clark on South Sister; and Lathrop on Mt. Thielsen.

Gaining a view of Mt. Thielsen’s north side where Lathrop Glacier had recently existed was the object of Ollie’s and my third climb that long, late September weekend. After descending Bailey, we moved to the Broken Arrow Campground south of Diamond Lake, though only after taking a dip in that lake, which itself occupies a valley formed by huge glaciers that formerly flowed off Mt. Thielsen, Mt. Bailey, Howlock Mountain, and Mt. Mazama. It was the last night of the season for the campground and only one other campsite (there are some 120 of them) was occupied. Just about 6 a.m. the next morning, on Monday the 26th, we started

continued on next page

our last climb—this one beginning at the head of the Howlock Mountain Trail #1448 at the northeastern corner of the lake. It was another beautiful morning as we climbed eastward toward Howlock Mountain through the recently burned area that only transitioned to forest near Timothy Meadows. There, at roughly 6,000 feet high, we came to the junction with Thielsen Creek Trail #1449. It veers off to the southeast and was the route we would return by that afternoon.

The Howlock Mountain trail above that point seems to have had little tending recently. It occasionally disappears into the forestfloor, and many times we had to make our way over, under, and around fallen trees. At about 6,840 feet high, we came to a massive blow down that took us a while to navigate. Two miles farther up, we hit the PCT, where 1448 ends. To reach Howlock Mountain from there (there is no trail to the summit), we headed in a southeasterly direction through somewhat open meadows and timber to the 7,960-foot-high saddle nestled between the summit of Sawtooth Ridge on the north and another, lower point, to the south. Whereas Ollie bounded freely through the relatively open meadows just above the PCT, as the route steepened, he stuck close to my heels. After cresting the saddle, we then headed eastward across talus slopes to Howlock’s true summit. We found a cairn at the top. I pulled from it a plastic peanut butter jar containing a pad and pencil where I recorded our names. While the makeshift register indicated that a small party had been there a couple days before, we were all alone and were so that entire Monday!

From the summit, we took in views that stretched from the Three Sisters to Shasta. But my eyes fell most discerningly on Thielsen, a peak I had climbed in 2021. It dominated the view to the south. Not far from where we relaxed was one of the locations that Ralph H. Nafziger began visiting in 1968 to observe and photograph Thielsen’s north face. In 1966 while on a climb of that peak, Nafziger’s

uncle Theodore Lathrop, who joined the Mazamas in 1961, had spotted there what he suspected to be a small glacier. He returned in 1968, this time with his nephew, and the two confirmed the presence of glacial ice. After Lathrop passed away in 1979, Nafziger, who joined the Mazamas in 1969, persuaded the Oregon Geographic Names Board to name what was then Oregon’s most southerly glacier “Lathrop.” It soon began appearing on maps. Over the years, Nafziger returned dozens of times to examine the ice body, and he reported his findings of its expansion and recession on

Lathrop from the world and provided its life-supporting shade. I wondered if any ice might still lurk there. Ollie and I packed up and descended to the PCT and followed it southward to where it fords Thielsen Creek, right where that small stream emerges from the base of the mountain that is its namesake. I got better views of those suspicious-looking snow patches from there, but was unprepared, especially with Ollie along, to challenge the lower talus slopes of Thielsen’s north face for a closer look. Instead, Ollie and I snacked and relaxed in the refreshing alpine meadow there made possible by the slowly melting snows that were once a glacier and that still feed Thielsen Creek. At that moment, I contemplated global warming, drought, and forest fires and imagined a future when whatever snow that falls there might melt away so early in the season that even Thielsen Creek, the only flowing stream we encountered all day, would itself dry up before summer’s end.

six occasions in the Mazama Annual. The last appeared in 2005. In it, and because of the glacier’s continued decline and the apparent rate of global warming, Nafziger predicted that Lathrop would disappear in about 2070. In fact, Oregon Glaciers Institute explains that it had vanished before 2020. When Lathrop melted away, Crook Glacier (which I still know as Crater Glacier) on Broken Top became Oregon’s most southerly glacier. But Ollie’s and my views of the south face of Broken Top from Bachelor Butte just a couple days before our ascent of Howlock suggested that practically nothing remained of that ice body either.

From Howlock’s summit, I spotted snow in the crevices that had once obscured

For our return trip, Ollie and I headed down the Thielsen Creek Trail #1449 to Timothy Meadows and its junction with Howlock Mountain Trail. From there, visions of cool streams, snow, and glaciers danced in our heads as the sun beat down mercilessly while we hiked through the burned-over area. In all, we covered 16.5 miles and had ascended some 3,000 feet that day. Although another night’s camping sounded appealing, our bedraggled condition instead led us to choose for home.

The very next day and back home, I started planning my climb of Diamond Peak. From the information I could gather, I thought it might be too challenging along the upper ridge for Ollie. And so, to his great chagrin and my lament, I closed our house door between us when I set out early the next Sunday morning, October 2nd.

I selected for my entry to the Diamond Peak Wilderness the head of Rockpile Trail #3632, rather than the more difficult to reach Summit Lake, where one approaches via the PCT. Rockpile, whose head affords good parking, commences at an elevation

of just under 5,200 feet. It is about 5.5 miles from there to the summit. At about half that distance, you reach the PCT and follow it a mile north and to an elevation of roughly 6,600 feet. There you turn onto a small cairn-marked climber’s trail. For my return and after descending the climbers trail, instead of following the PCT, I headed cross-country through the open forests down to Marie Lake’s eastern shore and near where I rejoined the Rockpile trail. I thereby cut off some distance and although I was really in no hurry, I was back at my car at 11:45 a.m. The entire time on Diamond Peak, I only encountered six people and that began happening well after reaching the summit and back down on the lower part of the climber’s trail. Among those I came across were two Mazamas, one with whom I had taken BCEP and the other ICS.

When I had set out at six o’clock that morning, and given that it was early October, I needed my headlamp to illuminate the way. I moved swiftly, though, reaching a high vantage in time to take in pre-sunrise views of Cowhorn Mountain, which I had climbed in 1986, and farther

to the south that jumble of high crests and pinnacles where Ollie and I had wandered a week earlier. After turning onto the climber’s trail, which soon dissolves into many difficult-to-follow traces through scree (the main route is easier to spot when descending), I mostly chose my course by keeping my sights on the 8,421-foot false summit that loomed above. It crowns the south buttress to the mountain. From there, one follows along the top and east side of the ridge northward about a half mile to Diamond Peak’s summit. Some large boulders and small precipices leave one to puzzle out the safest path along the way, but it was not so difficult that Ollie could not have made it, so long as I would have watchfully chosen the route for him.

The Oregon Glaciers Institute reports that in addition to Diamond Glacier, four other bodies of ice had historically existed on the mountain. Kenneth Phillips wrote that one of these had been visible from Odell Lake early in the 20th century and that eyewitness accounts claim it had disappeared in about 1920. Phillips referred to two other small cirques—one of which was in my view as I traversed

the southern ridge—that he had found so freshly barren in 1938 that glaciers must have only departed from them just before he investigated there.

In truth, my climb of Diamond Peak on October 2, 2022, had commenced a half-century earlier with my discovery of Phillips’s “Our Vanishing Glaciers.” As I made my way all alone up and up that last leg of this journey that began long before, I reflected on those early years when, in reports, maps, and libraries, I learned about our mountains and their vanishing glaciers. I also thought about my parents, no longer living, who had introduced me to the outdoors; the 1970 camping trip to Central Oregon that sparked my fascination with the Cascades; the places distant from the Pacific Northwest that my life had then taken me, sometimes for years at a time; the countless ways, many of them rather disconcerting, that our mountains had changed and were changing. More happily, I thought about my little four-legged climbing companion who waited for me at home. But I also wondered about Kenneth Phillips whom I continued on page 27

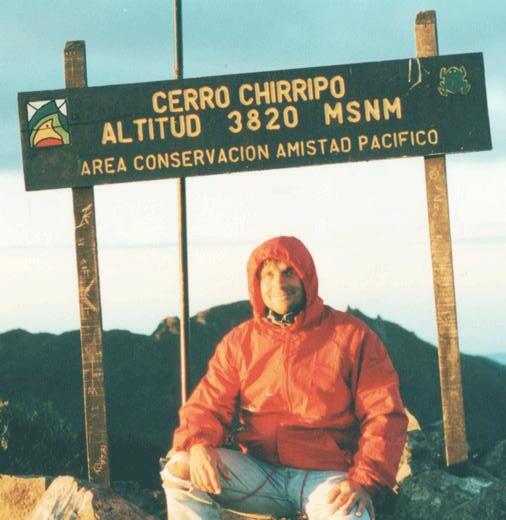

THE ROOF OF COSTA RICA

by Darrin GunkelChirripó National Park protects 125,000 acres of rainforest, cloud forest, and páramo (high altitude grasslands of Central and South America), surrounding Costa Rica’s highest peak, Cerro Chirripó. There’s no camping in the park, but visitors can stay at a simple lodge located 11,000 feet above sea level, and spend days wandering the peaks and valleys, lakes and plains of the massif that Cerro Chirripó is just one corner of. The park draws an assortment of travelers and adventurers from all corners of the world, who convene at the mountain hamlet of San Gerardo to begin their climbs. Following are journal excerpts from a four-day visit I made to the park a few years back, the high point, literally and figuratively, of a four-month trip exploring the wild lands of Central America.

At 4:30 I try to wake my roommate Dario but he complains “It’s still dark!” and pulls his covers over his head. My other climbing mates, Amy and Carlos, are sitting in their room, looking stunned and nowhere near ready to go. So I slog alone 25 minutes up San Gerardo’s one, steep road. The surface is lumpy, jagged, anklemunching concrete. A fine warm-up for the first section of the trail proper.

This route begins at 1,340 meters. It ends at the summit of Chirripó, 3,820 meters. I do the math, then wish I hadn’t: only 8,120 feet to go. The first hour has to be the most difficult. Rising through coffee plantations above San Gerardo, it’s a steep, rutted, eroded pile of loose rocks sliding down a mountainside. There are steps, but the trail is so washed out, some are close to 18 inches high. This is real work, better to

get it out of the way before the sun comes up and I’m fully awake and can register how painful it is.

At the top of the second hour the trail enters the park proper and a real forest, and the trail is suddenly much better. Cloud forest begins about 2,000 meters. Annoying little brown flies only bother me while walking – stop for a second and they’re gone.

At 8:15 I reach the shelter at Llano Bonito, 9.5 kilometers in, 2,400 meters up. The forest is excellent here—the shelter has a little observation deck on a second floor. Tall straight trunks of black oaks, plastered with lichen and moss, bromeliads, sprays of green and red, attached to the high branches. I hope to sight some wildlife, but instead, just get two loud huffing Yankees on their way down, claiming they’d rather

do this as a day hike. Dario catches up here and we play tag team the rest of the way, spending the next two hours scaling Cerro Sin Fe, which tops out at 3,200 meters. It’s a grind, rising through thinning forest, and then a cloud. At this point, the forest changes again, entering an old burn, black and silver trunks and twisted branches, green thicket at their feet. This stretch is difficult enough that it goes fairly quickly. Dario agrees, “You just grind away and think about anything else.”

The final hour is worse, descending for about a half hour. I don’t want to know how many hard won meters we’ve lost. A sign announces “Base Crestones 1.5 k” and the trail scales a mountainside. I wave goodbye to Dario, who’s stopping more often, and decide to make the final leg in one go.

The lodge at Base Crestones is a long one-story building set into the side of a mountain. Across the valley, Cerro Crestones, topped by fins of yellow rock. We’re at 3,400 meters, and 16 kilometers in. I stagger up to the office at 12:15, 7 hours from San Gerardo. Rent a sleeping bag and the ranger on duty shows me around—a big dining hall full of picnic tables—a shelf full of communal food. I’m impressed by how nice it all is. I laugh when the ranger says there are showers, but he’s not kidding. This place is posh! When Dario shows up it’s the ranger’s turn to guffaw, “No. We don’t have hot showers.” We share a bunk room with a French rock climber and a weathered-looking Austrian who decides to go up Chirripó now, even though the high peaks are drowning in clouds.

In the evening, the wind picks up and it begins to get cold. Socialize in the mess hall with an international crowd. Amy and Carlos have shown up, and are feeding everyone cups of hot tea. They’re from Miami, but are moving to the Dominican Republic after exploring Central America. The rest of the dining hall is filled with Costa Ricans, and someone mentions that 80 percent of the visitors to this park are locals. The Austrian describes the 10 kilometer round trip from here to the summit. A Canadian, Ashley, joins the

group and talks me into shooting for sunrise from Chirripó. I’m not a hard sell. So that means we’ll be getting up at 3 a.m. Not like there’s a late scene here—the lodge powers down at 8 p.m., but I crashed out a good hour before then.

The next morning, the advantage of our early start becomes apparent. It’s actually not that cold—yet. And we’ll be hiking through the 2 chilliest hours of the night. Down a bowl of granola in a daze. Ashley has a banana and Snickers, “Outside Magazine did a test—banana and a Snickers is just as good as a Cliff Bar.” Heretic! Then we step out into the night …

The wind is chilly. In the starlight I can see cloud caps on the peaks. Hiking in the dark is surreal. Totally focused on the ground, the flashlight beam picking out every rock and root in high relief. The páramo, the high altitude grassland we are crossing, smells weird, musky, animal. Our world is reduced to the 2 meters around us, a dream-like experience. I’m awake, I’m walking, but that’s the only resemblance to a normal hike. It’s far too early and I have yet to acclimatize, so we speak very little. The silence is huge—clouds have

descended, or maybe risen from below, blanketing sound and the few traces of sky light. The trail crosses a patch of rock and there’s a second of confusion until we methodically make our way around the edge of the bare patch to pick up the trail again. The break in our rhythm is jarring in this sense-narrowed, nearly meditative state. Rain. Or very thick cloud. Water drops on my flashlight lens cast mottled half shadows on the circle of light in front of me. The fog clears and I notice the stars have begun to fade. The Milky Way has lost the depth it had earlier. An assortment of peaks emerge before us. We decide one is Chirripó for no particular reason other than the trail seems headed for it. It’s not. On a saddle at its feet, the ground beyond our lights takes form and in the distance, the real summit. It is appropriately mountain-shaped, a steep pyramid surrounded by rounded knobs. continued on next page

The trail drops, crossing a scree slope, flat rocks clinking and thunking with our steps. Still too dark to tell how far we have to go, or how much we’ll have to climb on the steep summit slope. A ridge leads up to the base. There’s now enough light to make out dark splotches below on either side—lakes. The Austrian said the final climb is only 100 meters. Pocket my flashlight. There’s enough light now, and I’ll need my hands. This is the part where I start swearing; it looks a long way down on either side. I can’t make out any details, just the drop… Can’t see the top, either…

Until we’re suddenly on it, hauling up over one final lip of rock to find that everything—everything in sight—and in Costa Rica, for that matter—is now below us. Ashley and I shake hands and look around. The sky to the east is a cold blue, casting a dim glow on a plain of dark, lumpy cloud tops. High clouds are streaks of black, like scraps of night on the dawn. To the west, a colorless darkness out of which rise the first cumulus cloud stacks of the day, their bases lost in shadow, their tops more outlines or suggestions of clouds than solid, real shapes. Around us a dozen lower peaks on the Chirripó massif, tilting up out of cirques and U-shaped valleys and bowls with dim lakes in their bottoms. It’s gotten quite cold—5:05 a.m.—we beat the sunrise by half an hour.

Try to keep moving as the light grows. There’s a lot of wind up here. Details emerge on the ridges and peaks around us, their western slopes in deeper shadow. You can see two oceans from up here. The Caribbean is mostly buried under a plain of cloud stretching to the eastern horizon, now blazing white and yellow. Haze makes it difficult to tell exactly what we’re seeing down the Pacific slope. Maybe those lavender-ish patches in the purple gloom are glimpses of the sea? We wait as the sun doesn’t so much rise as boil its way out of the cloud deck. It’s worth it. We’re bathed in a yellow light, the tops of the Chirripó massif glow greenish yellow. The eastern sea of clouds goes white; purple mountains rise out of it at intervals all the way to the southern horizon.

By 6, the more spectacular cloud and light effects have ended. It’s still too beautiful up here, but time to go. The scramble back down the summit pyramid is less scary now that I can see. The walk back is going to be nice. The light up here is superb—so clear. The sky is a few shades

darker blue than at “normal” elevations. There are no clouds above us—only below, glimpsed lapping over lower ridges or creeping up valleys. Above all the dust, humidity and pollution, the sky looks infinite. We finally meet other hikers at that saddle—a group of older Ticos. Ashley tells me he met an 81-year-old Tico who summited. That fills me with optimism. I want to still be doing this when I’m 81.

Starting a hike in the dark makes the return trip seem like a whole different trail. We walk down through the Valle de los Conejos – our foggy stretch on the way up. It’s a broad, flat-bottomed bowl, ringed by dark slabs and knobs of rock tilting in a wall a thousand feet high. The trail contours down the shallow western side of the bowl, alternately sinking through alleys of tall reed-like shrubs, then crossing decks of rock polished and grooved by glaciers. Morning sun burnishes the edges of fat columns of black rock across the valley. Here in the jungly Costa Rica, land of rain, cloud, and dry forest, I’ve found truly wide open spaces, like a piece of Montana with all its emptiness and over-sized scale, its naked geology and bone-dry air, its stubbly carpet of tough-looking shrubs and its surprising hidden creeks and streams.

After the Valle de los Conejos the trail spills us back into the V-shaped valley below Crestones. Back at the base by 7:30, amused how early it is. Time for breakfast.

After, I read under the covers in my bunk, enjoying the peace and quiet here at 11,000 feet. Later, another hike: Sabana los Leones. The trail there contours up over the ridge across the valley. Nice walk through the silver forest of burnt trees growing out of a bed of golden tufts of grass.

The colors up here are strange— everything a greenish yellow or yellowish green—rocks, trees, bushes all tinted with this organic hue. The sky is desert blue. A short scramble leads up to a viewpoint of the Sabana—a shallow hanging valley about 3 miles away. More of that western US feel—pockets of greenery and stands of trees where the trail dips, but rocky, dry, weedy, mostly—and that sky and those long views—warm afternoon sun. I quit when the trail really begins to nose dive, content with a good view of the Sabana, clouds creeping over its edge in one direction, airplane view glimpses of the lowlands over its other shoulder, shrubs full of emerald hummingbirds behind me. Ashley appears and we just stare out a while. Easy to do here. He mentions the trail to Costa Rica’s second highest peak, Cerro Ventisqueros, begins right behind the lodge. Looks like we have a plan for tomorrow. Back at the base, watch the ridge of the Crestones go orange in the setting sunlight. I turn in not long after, relishing the thought I have two more days of roaming this tall range.

Vanishing Glaciers, continued from page 23

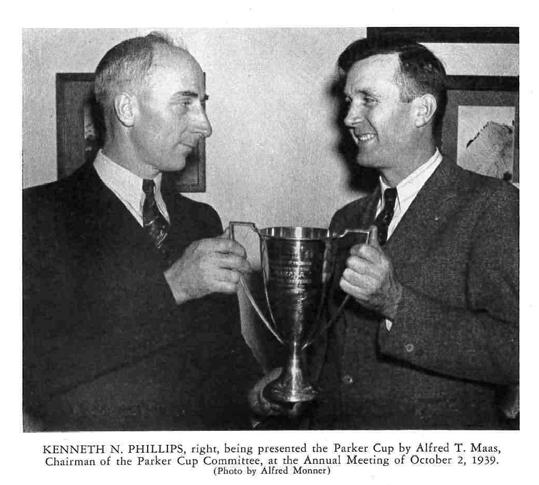

never met, but whose writings have meant so much to me through my life. In 1937, the year prior to reporting on Diamond Glacier, he led the Research Committee’s efforts to convince the U.S. Board on Geographic Names to name a small body of ice on Mt. Hood’s northwest flank in honor of our past president, Rodney Glisan. It did. But Glisan Glacier is also now no more; its passing yet one more disappearance noted by the Oregon Glaciers Institute in the last few years. The Mazamas presented Phillips the Parker Cup in 1939 for his many contributions to the organization. He passed away in 1995 at the age of 97. I utterly lost myself in these thoughts and in many others as I focused my attention on the summit of a mountain that, as I drew nearer and nearer to it, transformed into a metaphorical terminus to a significant journey in my life.

It was right that I should have found myself totally alone as I reached that summit that morning, even more alone than I had been when I first learned of Diamond Peak’s vanishing glaciers in the deserted map room of Portland’s Central Library on a Saturday morning long ago. But just as I gained my long-anticipated endpoint, my sense of aloneness also vanished. For, as I took in the views from what was the top of my world, I was astonished to find there, just a little off to the west, a very old friend—one I had never personally met before. Diminished and worn, persistent and ephemeral, its receding life yet clung to an ancient cirque that it had occupied since long before my time. It had greeted Kenneth Phillips there, too, back in 1938. But back then the glacier had stretched down the mountain another 2,000 feet, its moraines extending even farther down to below timberline. Phillips also observed some small crevasses in it, and flowing from its terminus the then milky, glacial effluent of Bear Creek. Most of what he called Diamond Glacier had disappeared down that creek over the years since. That something of it still remained when I finally made my long-anticipated pilgrimage there constituted a miracle–it seemed as if that glacial remnant had waited there patiently just for my arrival. So then, much like old friends, the two of us silently perched there together, high on that alpine ridge. And as I looked down the mountain into the shadows of that

vanishing glacier, I observed there a future fast approaching, while I thought an awful lot about a past quickly slipping away.

SUCCESSFUL CLIMBERS

April 26, 2023–Mt. Hood, South Side.

Pushkar Dixit, Leader; Sohaib Haider, Mark Mott, Assistant Leaders. Chris Boyle, Andrew Conley, Ian FitzGerald, Tommy Goodson, Avery Hashbarger.

May 28, 2023–Unicorn Peak, Snow

Lake. Lynne Pedersen, Leader; Carol Bryan, Assistant Leader. Christopher Boswell, Matthew Gantz, Tad Nicol, John Rowland, Sharon Selvaggio, Nathan Taylor.

June 2, 2023–Mt. Rainier, Ingraham

Direct. Pushkar Dixit, Leader; Peter Boag, Assistant Leader. Agreen Ahmadi, Douglas Filiak, Sohaib Haider, Josh Pertile.

June 2, 2023–Unicorn Peak, Snow

Lake. Gary Bishop, Leader; Nimesh Patel, Assistant Leader. Bashar Al-Rawi, Antonio Bezerra, Dennis Falcione, Krista Lawrence, Leah Madoff, Bartholomew Martin, Colin Miletich.

June 2, 2023–Rooster Rock, South

Face. Justin Colquhoun, Leader; Guy Wettetein, Assistant Leader. Steph Reinwald, Eleasa Sokolski, Zachary Warres, Midori Watanabe.

June 4, 2023–Mt. Ellinor, SE Chute.

Carol Bryan, Leader; Petra LeBaron-Botts, Assistant Leader. paul anderson, Kapil Dave, Mikhail Hakim, Kima Kheirolomoom, Olivia Markee, Erika Prats, Raelyn Thompson.

June 7, 2023–Mt. Hood, South Side.

Tim Scott, Leader; Peter Boag, Assistant Leader. Oliver Borg, John Catena, Mikhail Hakim, Cameron Harkness, Mark Maria, Bernie Murphy, Tyler Sievers, Scott Templeton.

June 10, 2023–Eagle Peak. Toby

Contreras, Leader; Ann Marie Caplan, Assistant Leader. Jessie Cunningham, M. Hansen, Colleen Rawson, Christin Ritscher, Carrie Spates, Lauren Walker.

June 11, 2023–Middle Sister, Hayden Glacier, North Ridge. Andrew Bodien, Leader; David Posada, Assistant Leader. Winnie Dong, Grayson Hughbanks, Truth Johnston, Priyanka Kedalagudde, Amanda Lovelady, Nachiket Rajderkar, Ariana Ramirez. June 11, 2023–Pinnacle Peak, East Ridge. Toby Contreras, Leader; Christin Ritscher, Assistant Leader. Erik Anderson, Ann Marie Caplan, Cecilia Estraviz, Mark Federman, Addy Martinez, Tyler Sievers.

June 11, 2023–South Sister, Devil’s Lake. Stacey Reading, Leader; Jesse Applegate, Assistant Leader. Chelsea Ashcraft, Brad Dewey, Marsha Fick, David Gross, Gabriel Guzman, Alex Homer, Kira Smith, Caroline Stanley, Merche Trol.

June 11, Unicorn Peak, Snow Lake. Christine Troy, Leader; Prasanna Narendran, Assistant Leader. Max Ciotti, Heidi Griffith, Anna Kolodziejski, Kelly O’Loughlin, Theo Pham, Amanda Thomas.

June 12, 2023–Unicorn Peak, Snow Lake. Carol Bryan, Leader; Lynne Pedersen, Assistant Leader. Paul Anderson, Mario DeSimone, Mark Federman, Michael French, Nicolas Martinez, Jonathan Shaver, Evan Sloyka.

June 15, 2023–Middle Sister, Hayden Glacier, North Ridge. Pushkar Dixit, Leader; Jen Travers, Assistant Leader. Chris Burreson, Avery Hashbarger, Sangram More, Matt Mudrow, Karthik Periagaram, Elizabeth Reed, Aaron Stahr, Midori Watanabe, Sydney Yelton.

June 16, 2023–Colchuck Peak, Colchuck Glacier. John Sterbis, Leader; Kevin Ritscher, Assistant Leader. Lily Cox-Skall, Jessie Cunningham, Whitney Harvey, Dylan Pickford, Chris Reigeluth, Mark Stave.

June 16, 2023–Mt. Hood, South Side. Tim Scott, Leader; Thomas Clarke, Assistant Leader. Tyler Bolton, Jonathan Doman, Maelle Gery, Margaret Munroe, Ria Nochera, Andrea Ogston, Theo Pham, Tim Roy, Arjun Sudhir, Nikki Thompson.

June 17, 2023–Castle, Pinnacle, & Plummer Peaks, Standard Route. James Jula, Leader; Anibal Rocheta, Assistant Leader; Ryan Reed, Janelle Klaster, Volunteer Leaders. Kapil Dave, Nick Dolja, Joshua Gerth, Ali Marie Koch, Kiana Saluni, Michael Smith, Frank Squeglia, Kelsey Sullivan.

June 17, 2023–Unicorn Peak, Snow Lake. Guy Wettstein, Leader; Laetitia Pascal, Assistant Leader. Chelsea Ashcraft, Matt Cleinman, Steven Peterson, Mark Pothier, Caroline Stanley, Emily Telford-Marx, Yukiko Toyoda, Merche Trol.

June 18, 2023–Unicorn Peak, Snow Lake. Ryan Reed, James Jula, Leaders; Janelle Klaser, Volunteer Leader. Kapil Dave, Nick Dolja, Joshua Gerth, Ali Marie Koch, Anibal Rocheta, Kiana Saluni, Michael Smith, Frank Squeglia, Kelsey Sullivan.

June 20, 2023–Mt. Hood, South Side. Tim Scott, Leader; Janelle Klaser, Assistant Leader. Jacob Hagg.

June 24, 20-23–Mt. Baker, Easton Glacier. Darren Ferris, Leader; Mark Stave, Assistant Leader. Peter Boag, Mario DeSimone, Dani Larson, Dzmitry Lebedzeu, Karthik Periagaram.

June 24, 2023–Santiam Pinnacle, South Face. Karen Graves, Leader; Andrew Leaf, Assistant Leader. Jeremiah Biddle, Carol Bryan, Linda Musil, Elizabeth Reed, Steph Reinwald, Tuller Schricker, Elena Weinberg.

June 24, 2023–Unicorn Peak, Snow Lake. Kirk Newgard, Leader; Steve Polansky, Assistant Leader. Lydia Alderfer, Jeevitha Babu, Cecilia Estraviz, Jerrid Kimball, Tanvi Singh, Arjun Sudhir, Eric Windham.

June 25, 2023–Unicorn Peak, Snow

Lake. Greg Scott, Leader; Janelle Klaser, Assistant Leader. Patricia Akers, David Gross, Jacob Haag, Alex Homer, Courtney Ianello, Alex Kunsevich, Connor Lieb, Evan McDowell, Tim Scott.

June 26, 2023–Castle/Pinnacle, Standard Route. Greg Scott, Leader; Sohaib Haider, Assistant Leader. David Gross, Jacob Haag, Alex Homer, Courtney Ianello, Janelle Klaser, Alex Kunsevich, Connor Lieb, Evan McDowell, Tim Scott.

June 26, 2023–Middle Sister, Hayden Glacier, North Ridge. Joe Preston, Leader; Josh Lockerby, Assistant Leader. Andrew Behr, Max Ciotti, Jessie Cunningham, Heidi Griffith, Thomas Owens, Nicholas Peeters, Malcolm Reilly, Jules Williams, Ryan Zubieta.

June 26, 2023–Mt. Adams, South Side. Judith Baker, Leader; Duncan Hart, Assistant Leader. Alastair Cox, Brad Dewey, Raju Jha, Jerrid Kimball, Beatrice Robinson.

June 26, 2023–The Tooth, South Face. Ryan Reed, Leader; James Pitkin, Assistant Leader. Alex Aguilar, Agreen Ahmadi, Jonny Cushing, Nicolas Martinez.

June 30, 2023–East Wilman’s Spire. Glenn Widener, Leader. Mark Stave, Sangram More, Linda Musil, Sohaib Haider, Lisa Ripps.

June 30, 2023–Mt. Shasta, Clear Creek. Gary Bishop, Leader; Evan Smith, Assistant Leader. Dennis Falcione, Casey Ferguson, Jeremy Luedtke, Hannah Raynor.

July 1, 2023–Gothic Peak, East Side. Glenn Widener, Leader. Conrad Cartmell, Mike Quigley, Lisa Ripps, Kathryn Villarreal.

July 1, 2023–Unicorn Peak, Snow

Lake. Pushkar Dixit, Leader; Massimiliano Gallo, Assistant Leader. Leah Brown, Chris Burreson, Winnie Dong, Caroline Foster, Avery Hashbarger, Raju Jha, Matt Mudrow, Dylan Pickford, Gary Riggs, Saraja Samant.

July 8, 2023–Del Campo Peak, South Gully. Tim Scott, Leader; Kevin Ritscher, Assistant Leader. Judith Baker, Emily Carpenter, Lori Coyner, Rachel Faulkner, Jerrid Kimball, Petra LeBaron-Botts, Dylan Pickford, Astrid Zervas.

July 8, 2023–Gothic Peak, East Side. Tim Scott, Leader; Kevin Ritscher, Assistant Leader. Patricia Akers, Judith Baker, Emily Carpenter, Lori Coyner, Rachel Faulkner, Jerrid Kimball, Petra LeBaron-Botts, Dylan Pickford, Amanda Thomas, Astrid Zervas.

July 8, 2023–Mt. Adams, South Side. Guy Wettstein, Leader; Thomas Clarke, Assistant Leader. Matt Cleinman, Robert Erickson, Megan Lien, Cait Lotspeich, David Posada, Elizabeth Reed, Arjun Sudhir, Sydney Yelton.

July 8, 2023–Mt. Rainier, Kautz

Glacier. Aimee Filimoehala, Darren Ferris, Leaders; Sohaib Haider, Assistant Leader. Jonny Cushing, Sohaib Haider, Rob Sinnott.

July 9, 2023–Mt. Adams, South

Side. Ryan Reed, Leader; Toby Contreras, Assistance Leader. Eleanor Bold, Casey Ferguson, Matt Gardner, Mikaila Horan, Kellie Peaslee, Dan Rehmann, Kiana Saluni, Tyler Sievers, Lauren Walker.

July 12, 2023–Rooster Rock South

Face. Guy Wettstein, Leader; Forest MenaceThielman, Assistant Leader. Jeremiah Biddle, Leah Brown, Chris Reigeluth, Tuller Schricker, Kathryn Villarreal.

July 14, 2023–Mt. Thielsen, West Ridge. Pushkar Dixit, Leader. Jeevitha Babu, Chris Burreson, Kapil Dave, Raju Jha, Priyanka Kedalagudde, Alex Kunsevich, Matt Mudrow, Bikash Padhi, Elizabeth Reed, Tuller Schricker, Aaron Stahr.

July 14, 2023–Old Snowy, Snowgrass Flats. Lisa Ripps, Leader; Mike Quigley, Assistant Leader. Alastair Cox, Mark Federman, Michael Hynes, Joanne Morris, Walker Pruett, James Taylor, Midori Watanabe.

July 15, 2023–Mount St. Helens, Monitor Ridge. Gary Bishop, Leader; Emily Carpenter, Assistant Leader. Dennis Falcione, Cait Lotspeich, Jeremy Luedtke, Leah Madoff, Andrea Ogston, Yaadhav Raaj, Candice Smith.

July 15, 2023–Pinnacle Peak, East Ridge. Joe Preston, Leader; Christine Troy, Assistant Leader. Whitney Harvey, Aaron Kaufman, Mike McTernan, Mike Quigley, Arjun Sudhir, Zachary Warres.

July 15, 2023–Unicorn Peak, Snow Lake. Vas Malik, Leader; Ann Marie Caplan, Assistant Leader. Tyler Bolton, Matt Egeler, Nicole Egeler, Douglas Filiak, Elizabeth Hill, Jacob Lippincott, Olivia Markee, Donica Polce, Dustin Putt, Kathryn Villarreal.

July 18, 2023–Mt. Washington, North Ridge. Kirk Newgard, Leader; Eloise Bacher, Assistant Leader. Lydia Alderfer, Anthony Carr, Max Ciotti, John Facendola, Kyra Jeffrey, Ada Marie, Devyn Powell.

July 22, 2023–Mt. Shuksan, Fisher Chimneys. Tim Scott, Leader; Walker McAninch-Runzi. Peter Allen, Emily Carpenter, Milton Diaz, Astrid Zervas.

July 24, 2023–Sahale Mountain, Sahale Glacier. James Pitkin, Leader;

Jeremy Galarneaux, Assistant Leader. Winnie Dong, John Rowland.

July 28, 2023–The Tooth, South Face. Pushkar Dixit, Leader; Rachal Faulkner, Assistant Leader. Chris Burreson, Conrad Cartmell, Hector Gomez-Barrios, Sangram More, Saraja Samant.

July 29, 2023–Ingalls Peak, South

Face. Pushkar Dixit, Leader; Rachel Faulkner, Assistant Leader. Akrita Agarwal, Chris Burreson, Sangram More, Jacqui Ogle, Saraja Samant.

July 29, 2023–Mt. Baker, Easton

Glacier. Trey Schutrumpf, Leader; Walker McAninch-Runzi, Assistant Leader. Marissa Burke, Harry Colas, Michelle McConnell, Laetitia Pascal, Kirk Rohrig, Vivian Ton.