First, eliminate random traffic stops. Then, abolish the police.

PG. 5 PGs. 8-9

Rolling the dice on academic freedom Help…my fridge is bare PG. 11

wrong with world music?

First, eliminate random traffic stops. Then, abolish the police.

PG. 5 PGs. 8-9

Rolling the dice on academic freedom Help…my fridge is bare PG. 11

Content Warning: Mention of sexual violence and racism

McGill’s Policy on Harassment and Discrimination allows members of the university community to take action when they feel they have been harassed or discriminated against. The policy outlines how to file reports and carry out investigations into individuals at McGill and the university’s systemic practices.

My first-ever div ing lesson ended with a 20-minute cry on the three-metre springboard and then a tearful drive home where I begged my dad not to make me go back.

I have three main de fences of myself here: I

was eight years old, terri fied of heights, and there against my will. My older sister wanted to try div ing and my dad is a strict believer in “if one of you goes, both of you go,” so that’s how I ended up sob bing in the London, On tario aquatic centre on a fateful Wednesday night in September. Whether he had my embarrassingly in tense fear of being above

the fifth floor of a building in mind when he signed us up, I’ll probably never know. What I do know is that in the years that fol lowed, I easily spent hours crying on pool decks. While that might not sound like a positive ex perience, diving equipped me with a confidence and trust in myself that I carry with me to this day.

While it is intended to provide support to students navigating the official complaint process, many—including Black and 2SLGBTQIA+ students, and members of student advocacy groups—are dissatisfied with the policy’s framework and implementation.

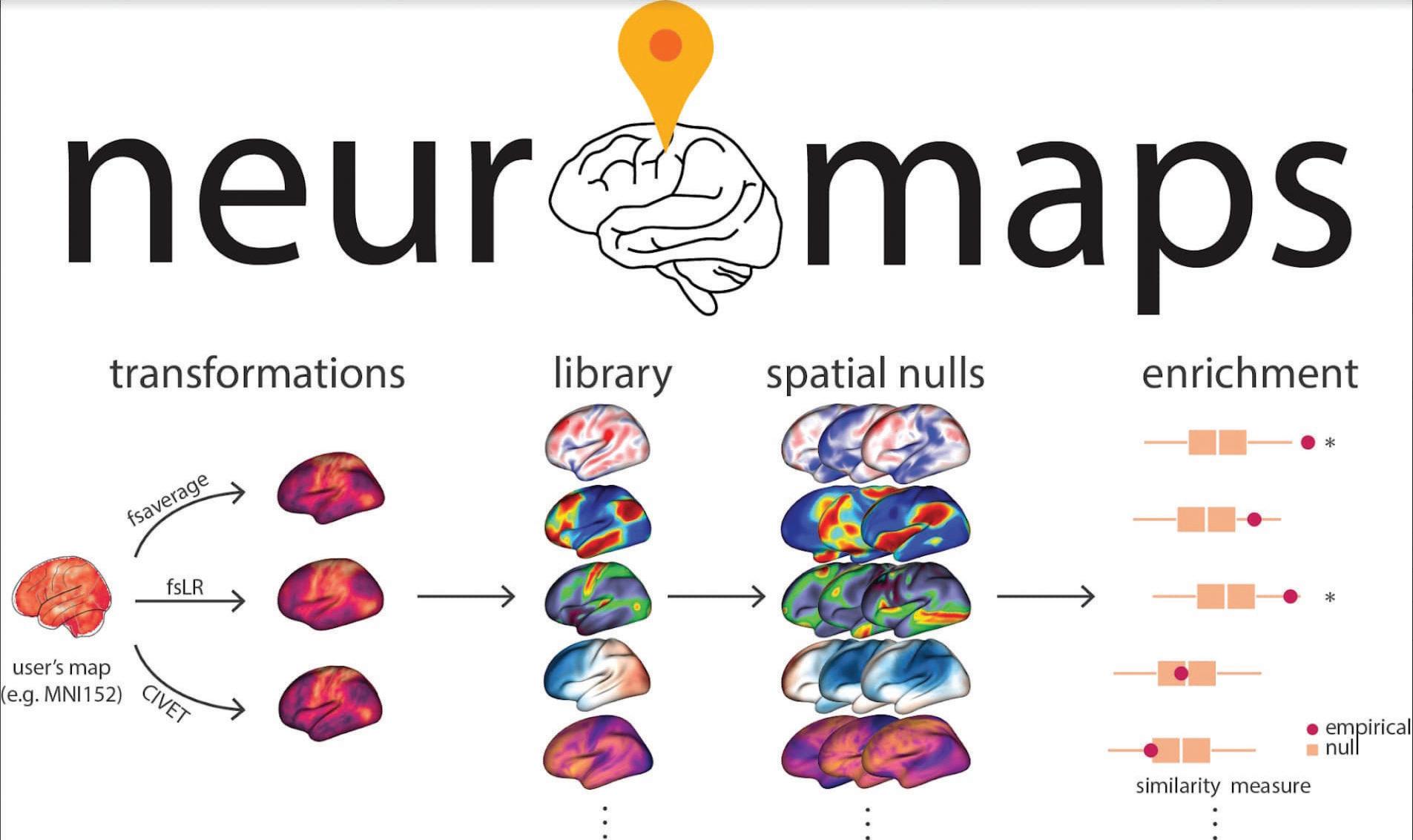

A team of McGill researchers published a paper in Nature Methods showcasing neuromaps, an open-source Python tool box that allows neuroscien tists to analyze brain imag ing data using a consistent

set of tools and compare it with a curated brain-map database. PhD candidate Justine Hansen, one of the paper’s first authors, spoke with the The McGill Tri bune about how neuromaps works and what she hopes it will accomplish.

Neuromaps gives re searchers a set of soft ware tools to transform

data from one format to another without having to perform the calculations themselves. At the same time, it pulls together a da tabase of about 40 standard brain maps that researchers can compare their data to, and a set of “spatial nulls,” which are tests for statisti cal significance in the data.

Continued from page 1.

In interviews with The McGill Tribune , student advocates familiar with the policy explained that they have found several issues with it, such as inefficient procedural practices and a lack of legitimate thirdparty intervention.

Complaints about harassment or discrimination are brought to McGill’s Office for Mediation and Reporting (OMR), which was created after the policy’s revision in 2021. McGill media relations officer Frédérique Mazerolle explained it as “an office dedicated to the independent and impartial oversight of the resolution of reports of harassment, discrimination, and sexual violence” in an email to the Tribune

Once a complaint is filed with the OMR, assessors—typically members of the university’s staff—begin the investigation process. According to section 6.2 of the policy, reports may be handed to an external thirdparty assessor if one of the investigators has a conflict of interest, if one of the parties is a member of the OMR, or if one of the parties is a member of McGill’s senior administration. Regardless of whether the assessor is an independent party or not, the Provost is responsible for making a final decision that concludes the investigative process.

“If the assessor’s report determines that the evidence is sufficient to find that harassment and/or discrimination has occurred, then the Provost will inform the parties in writing of

the decision to refer the matter to the appropriate University disciplinary authority to determine disciplinary and/ or administrative measures,” Mazerolle wrote.

A case’s appropriate disciplinary authority depends on the role of the accused, according to section 6.16. The appropriate authority in the case of a student is outlined in the Code of Student Conduct and Disciplinary Procedures. In the case of a staff member, it will be the dean of their faculty or the dean’s delegate, whereas in the case of a Vice-Principal, it would go to the Principal. The Chair of the Board of Governors presides over cases involving the Principal.

Queer McGill administrative coordinator Brooklyn Frizzle is concerned about what they believe is the Provost’s outsized role in managing harassment and discrimination complaints.

Frizzle stressed that a Provost’s individual biases can have an impact on how cases are handled. They pointed to previous comments that the former Provost and current Interim Principal Christopher Manfredi made in Senate meetings.

For example, Frizzle took issue with Manfredi’s indication—during a Nov. 18, 2020 Senate Meeting—that there is no inherent concern with McGill professors signing a petition to support a professor using racial slurs in their teaching.

In an interview with the Tribune , Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU) vicepresident (VP) University Affairs Kerry Yang explained that the OMR might not be completely detached from the university given it fits within the Equity

department under the Office of the Provost and remains under the administration’s jurisdiction.

“Although they say it’s all to remain impartial, based on how the structure is, it doesn’t seem that way,” Yang said. “There's no recourse if [McGill does] conduct something in bad faith because it’s all centralized. How can we ensure that what [McGill] is saying is impartial is truly impartial?”

Frizzle also takes issue with how the Policy serves 2SLGBTQIA+ students. They explained that many queer students who tried to file a complaint under the policy were advised by the OMR that their complaint would not be successful in an “investigative setting,” which ultimately discouraged them from seeking justice.

“Most of those cases are not investigated. They're not formally documented and there's no assessment made, typically, because they're kind of prescreened,” Frizzle said. “They advise a student that now this doesn't meet the definition, so it probably wouldn’t go anywhere.”

The most recent annual report on the Policy on Harassment and Discrimination noted that only eight per cent of inquiries with the OMR led to formal reports in 2020-2021. However, 47 per cent of all inquiries met the definitional requirements to launch a report.

Alex*, a student advocate, believes there are purposeful factual errors and omittances in McGill’s records.

“Many other Black students had filed harassment and discrimination complaints under McGill’s policy, and [...] it wasn’t conducted properly in the sense that [McGill] literally lied,” Alex

explained in an interview with the Tribune . “There were factual mistakes in the [reports]. They failed to include key elements, so it was intentionally not done properly.”

Alex compared the Policy on Harassment and Discrimination to the university’s Policy against Sexual Violence (PSV), which they believe is much more robust due to continued momentum from the #MeToo movement.

“Oftentimes when there’s a movement and there’s this kind of shift, like social pressure on a particular issue, sometimes it’s [...] tied to a specific momentum and then it fades,” Alex said.

“In [the case of sexual violence policies], we see this continuous legislative improvement and oversight. But when it comes to harassment and discrimination, it’s not the same.”

Frizzle explained that another reason McGill may prioritize updates to the PSV could be its provincial legal obligations. Bill 151 mandates universities to establish strong policies addressing sexual violence, whereas there are no specific laws mandating universities to institute policies against harassment and discrimination.

“McGill is a very big fan of the bare minimum, legally,” Frizzle said. “So, of course, they are going to take it more seriously because if it’s found that they're not investigating sexual violence, then that has a much bigger [...] legal implication than [...] failing to address harassment and defending professors that use racial slurs in our classroom and uplifting the voices of people who perpetuate injustice.”

The additional staff members who are employed to assist in anti-discrimination policy-

making often occupy roles with limited abilities. Alex explained that the Black Students Liaison Officer, who is responsible for supporting Black students, is not allowed to engage in any advocacy or directly aid students who have filed complaints. They also noted that McGill has recently eliminated the position of Assistant Dean (Inclusion - Black and Indigenous Flourishing), who was tasked specifically with supporting and recruiting Black and Indigenous law students. This position has been replaced with the Assistant Dean (Students), who carries out several student affairs duties in addition to being the dean’s lead on Black and Indigenous flourishing.

Both Yang and Alex believe that McGill’s Policy on Harassment and Discrimination must be revised to make it a more effective support mechanism. The most efficient way to conduct investigations, they say, would be entirely through an independent third party. Alex also suggested increased levels of academic accommodations for students during the complaint process and a provision to encourage advocacy throughout McGill’s governance channels.

“Every time I go to [governance] meetings, white administrators always say that ‘we don’t do any advocacy,’” Alex said. “But if we’re talking about equity issues and we're trying to improve a structure, the whole point is to demand that these structures be more equitable, and that requires advocacy.”

*Alex’s name has been changed to preserve their anonymity.

The Policy on Harassment and Discrimination will be up for its triennial review in the 2024–2025 academic year. (Maeve Reilly / The McGill Tribune)The Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU) held its Fall 2022 Referendum from Nov. 14 to Nov.

18. The two questions on the online ballot were whether McGill’s undergraduate student body was still in favour of funding the Daily Publications Society (DPS) and the Sustainability Projects Fund (SPF). Both motions passed, safeguarding the DPS and SPF’s current operations until the next referendum in five years.

The DPS is responsible for the publication of the independent student newspapers The McGill Daily and Le

Délit, the latter being the only francophone paper on campus. The DPS is entirely funded by student fees, and its existence is dictated by a Memorandum of Agreement (MoA) with McGill. In order to renew its MoA with the DPS, which expires in 2023, the administration requires that a referendum be conducted to prove continued financial support from students.

The SPF, created in 2010, is used to fund sustainabilityrelated projects at the university. It is jointly subsidized by McGill and students, with the school matching what students pay. The SPF student fee is outlined in the MoA between SSMU and the administration.

Noème Fages is the chief elections officer of Elections SSMU, the organization that runs the Society’s referenda. In a statement to The McGill Tribune, Fages described the newly tweaked schedule that was implemented this past election, which was intended to increase discussion and, ultimately, voter turnout among students.

“For this Fall Referendum, we chose to have overlapping campaign and polling periods to maximize student engagement with the referendum and make sure all students know about the referendum and its implications,” Fages wrote.

Last week, 22.6 per cent of eligible voters cast their ballots—the highest turnout achieved in a fall referendum since 2018, which had seven questions compared to this most recent election’s two.

Still, only about 5,000 students out of 23,542 eligible voters cast their ballots. Elliott Kalt, U1 Science, told the Tribune why he ended up not voting.

“I think most students tend to ignore SSMU emails because they send so many of them,” Kalt said. “I really believe that the newspaper[s] should be funded, however I understand that a lot of students might not have the financial ability to [continue

paying the DPS fee], so it's a very hard topic to vote on.”

On the ballot this fall was SPF’s mandatory fee of $0.55 per academic credit, up to 15 credits, which subsidizes the program. The Fund’s Governance Council (GC) distributes its million-dollar annual budget to students, faculty, and staff whose sustainability projects are approved. Shona Watt, a sustainability manager at the McGill Office of Sustainability (MOOS), was excited to see continued support for the SPF from students.

“[The Fund] is a resource for all McGill community members to launch or grow a sustainability initiative on campus [and] spark positive change in their own learning and work environment,” Watt said. “We are thrilled by the level of enthusiasm reflected in the results of the SSMU referendum.”

Ryan Stainsby, U0 Arts, ultimately voted “Yes” on financing the SPF for the remainder of his time at McGill.

“[The SPF] funds projects that work on making our campus more sustainable, more environmentally friendly [....] I think that’s really phenomenal,” Stainsby said. “I still understand if someone voted no for monetary reasons [....] Every dollar counts, you know.”

Voters also decided to uphold the DPS’s $6, non-optoutable fee, which has been charged to all undergraduates once per term since 2010 and is responsible for their nearly $300,000 budget.

Throughout the campaign and polling periods, both DPS papers stressed the importance of their continued existence, releasing editorials chronicling the publications’ work, tabling around campus, and posting testimonials from alumni on social media to encourage students to vote. The editorial boards of both publications thanked students for their support over Instagram after the referendum results were published.

Nov. 16 marked the final day of hearings against Bill 21 at the Court of Appeal of Quebec in Montreal. The legislation has faced controversy because it prohibits people employed in the public sector from wearing visible religious symbols at work and preemptively invoked the notwithstanding clause. Over five non-consecutive days, civil liberties groups, including the Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA) and the National Council of Canadian Muslims (NCCM), argued against an April 2021 decision by the Superior Court of Quebec that upheld most aspects of the Bill.

Among those protesting outside the courthouse on Nov. 7, when the hearings began, was the McGill Coalition Against Bill 21, which is composed of students, staff, faculty, and other McGill community members who oppose the law.

The 17 groups challenging the Bill argued that the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ)’s use of the notwithstanding clause―section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms― was invalid. The notwithstanding clause allows Parliament and provincial legislatures to shield legislation from any provisions in sections 2 (fundamental freedoms) and 7 through 15 (legal rights and equality rights) of the Charter.

Plaintiffs opposed Bill 21 on the grounds that the notwithstanding clause does not protect the Bill against section 28 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which guarantees equality between the sexes.

Elizabeth Elbourne, a professor in the department of History and Classical Studies at McGill, is “deeply troubled” by the invocation of the notwithstanding clause, and hopes to see the court acknowledge the effects the Bill has on women, in particular.

“It would be good to hear a ruling on gender grounds, that it had a disproportionate impact on women, and that there is, therefore, a ground which would exempt [the Bill] from the purview of the notwithstanding clause,” Elbourne said in an interview with The McGill Tribune

She added that she has witnessed the ramifications of Bill 21 herself at McGill.

“I had a student who was going to do a [master’s degree] with me, and who withdrew and left Quebec as a result of the law,” Elbourne said. “I met a student last month who used to wear [a] hijab and had to stop because of the law, but found it a very difficult and upsetting decision.”

Ehab Lotayef, a systems manager at McGill’s Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and a member of the McGill Coalition, believes that the language used in Bill 21 inordinately targets Muslim women.

“The word symbol is very misleading [....] A Muslim man, for example, can wear certain necklaces or chains with a certain symbol. That is

very optional, that’s what a symbol is,” Lotayef said in an interview with the Tribune. “But when a Muslim woman is covering her hair, she does not consider that [...] an option, or consider that a symbol.”

A study conducted under the leadership of Maryse Potvin from L’Université du Québec à Montréal (UQÀM) surveyed the effects of Bill 21 on education faculties. Bronwen Low, a McGill associate professor of integrated studies in education and a member of Potvin’s team, shared some of their findings with the Tribune

“Although the [Bill] is not to affect student teachers, findings from among the 972 survey respondents associate [Bill] 21 with negative and discriminatory treatment of student teachers, more polarized and conflictual interactions in

university classrooms, and negative effects on the well-being and academic and professional achievement of students,” Low wrote.

The ramifications of the Bill extend beyond unpleasant classroom environments. Ghania Javed, U3 Arts and Arts Undergraduate Society (AUS) president, recalled conversations with students who fear Bill 21’s potential detriment to their future careers in Quebec.

“I heard from one student that she’s considering going to Ontario after graduating from McGill Law because she’s not sure if by the time she will be practicing law, the Bill will [still] be here,” Javed told the Tribune. “Obviously if you want to work for the government, you have to choose between your career and wearing a religious symbol.”

conclude, reinvigorate

from members of McGill community McGill community members condemn gendered ramifications of BillSeventeen separate groups challenged Bill 21 at hearings on Nov. 7, 8, 9, 10, and 16. (cbc.ca)

Content warning: Mention of sexual violence.

On Nov. 16, the Post-Graduate Student Society (PGSS) held its Fall General Meeting to update members on the upcoming winter referendum, the 2023 executive election, and to discuss current PGSS initiatives. The meeting, however, did not meet its quorum requirement of one per cent of the total graduate membership. The motions presented could therefore not be passed and will instead reappear in the form of referendum questions in March 2023.

Studentcare, which provides opt-outable healthcare coverage to PGSS members, is extending its legal protection program to include consultation and representation for survivors of sexual violence. The goal of the initiative is to expand sexual violence care. The PGSS speaker broached the topic of how to ensure that the care provided would be comprehensive and inclusive to all graduate students.

Vegas Hodgins, a second-year PhD candidate in the Department of Psychology, would like to see Studentcare make sexual violence care accessible to all students, regardless of gender.

“I think that something that will be really important to engage with the Studentcare people [about] is [if] the [...] legal representatives they would be referring people to are ready to engage with victims of sexual violence who aren't cisgender women,” Hodgins said. “When it comes to treating the needs of transgender or even male victims of rape, there isn't that degree of understanding and it can be retraumatizing to engage with people who are just not understanding you in that way.”

The meeting also addressed a new PGSS initiative to increase access to gender-affirming care, which would help cover the costs of materials, medications, and gender-affirming surgeries for transgender graduate students. Rine Vieth, a PhD candidate in anthropology, suggested that the extra costs incurred that are indirectly tied to health care services should also be covered by the fund. Vieth cited a personal experience in which McGill Human Resources failed to respond to their requests to correspond with the Department of Anthropology, forcing Vieth to teach in person shortly after a mastectomy.

“I would also encourage that fund to go towards not just materials or medication, but things like the fact that people might not be able to work, and working with McGill to figure out ways to secure accommodations,” Vieth said. “I was forced to work [two and a half] weeks after my top surgery because McGill HR told me that I wasn't eligible to take time off and that if I wasn't able to do my job immediately after that, I would lose it.”

Many attendees also agreed that other gender-affirming costs, such as facial hair removal, or changing names and gender markers on legal documents, should be covered by the fund. PGSS Member Services Officer Naga Thovinakere assured attendees that these

concerns would all be taken into consideration.

“It's still in preliminary stages and the hope is that we reach out and ask for feedback at every step of the way,” Thovinakere said. “That way, we are setting this up in the most efficient way possible, as well as serving the needs of the people that need it the most.”

Other topics of discussion included health care accessibility issues, the PGSS social media and website presence, and the need to fill available committee positions for graduate students.

Prior to the General Meeting, the PGSS Council held a meeting of its own. While the general meeting was supposed to begin at 7:15 p.m, extended voting and discussion within the Council forced it to begin at 8:06 p.m.

“We really need people to serve on committees [....] They sound small, they sound unglamorous, they are certainly not as sexy as writing ‘Senate’ on your CV, but [they are] actually where important decisions that do directly impact people’s day-to-day lives as students happen.”

—PGSS Secretary General Kristi Kouchakji.

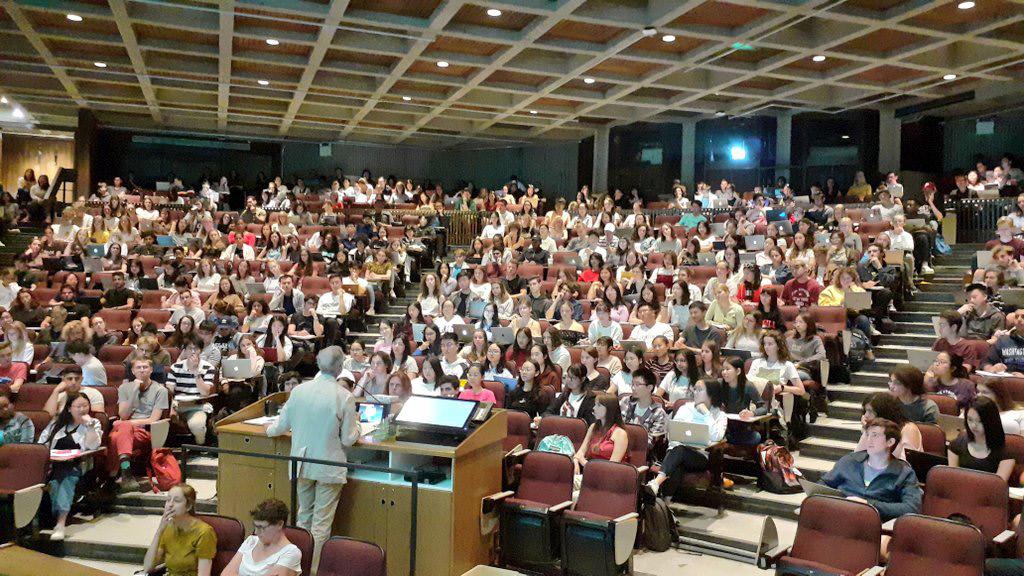

The McGill Senate convened in room 232 of the Leacock Building for the third meeting of the academic year on Nov.

16. Senators delved into reports from the Senate Nominating Committee and Academic Policy Committee, and participated in an open discussion on the university’s evaluation of “academic

excellence” among professors. After several Senate committees presented their annual reports, conversation turned to recent donations and McGill’s New Vic Project.

Christopher Manfredi, Interim Principal and Vice-Chancellor, opened the meeting by addressing the recent provincial elections and expressed his wishes for better engagement with the re-elected government. Discussion then broke into tables of senators, who were asked to ponder how the university community conceptualizes “academic excellence for academic staff.”

When presenting the Annual Report on the Investi gation of Research Misconduct, Dr. Christina Wolf son mentioned a general rise in cases flagged for investigation, with funding now being spared for a Research Integrity Officer. Wolfson described an “in crease in the number of anonymous allegations from colleagues,” which was met with nervous laughter amongst many in the Senate.

“I would really like to thank the disciplinary officers for their service, this is not a fun job to do.”

— Dean of Students and professor Robin Beech, upon presenting his first in-person Annual Report on the Code of Student Conduct

Senator Patrick Hansen, an associate professor at the Schulich School of Music, pointed out that measures of “excellence” will be evaluated uniquely in every discipline. Terri Givens, professor of political science and the Provost’s Academic Lead and Advisor on McGill’s Action Plan to Address Anti-Black Racism, elaborated on how traditional measures of “excellence” can work against those in marginalized fields.

“I’ve experienced this personally, when you are working in areas that are considered, you know, on the sidelines of a discipline, it's often difficult to publish in the top journals,” Givens said. “We have to be very careful about [...] how we assess these things like h-scores, [which] don't necessarily apply. Somebody can be seen as a really top scholar in a field that just doesn't get a lot of the same traction as other fields.”

Senator Sam Baron, a student representative for the Faculty of Arts, pointed out the importance of centring the student experience by hiring good lecturers, not just good researchers.

“The professors who are going to be here permanently in such a capacity should, of course, be the best of the best at passing their knowledge on to the next generation of students who are coming into the field,” Baron said.

In response, Manfredi admitted that McGill has not yet found the perfect mechanism for evaluating both the research achievements and the teaching prowess of teaching staff.

The Senate then moved to the Annual Report on University

Advancement, which outlined the donations made to McGill during the 2022 fiscal year, over which a total of $241.8 million was raised in gifts and pledges.

“Donors have helped us build the number one student aid program in Canada, allowing us to welcome the second largest proportion of students from lower socio-economic backgrounds in the province of Quebec,” said Vice-Principal (University Advancement) Mark Weinstein. “We also launched, during the pandemic, the student emergency fund, and in the past year we received over $130,000 in gifts from over 1,000 donors for this important cause.”

David Vaillancourt, a senator representing undergraduates from the Faculty of Engineering, questioned how the university will fundraise for the New Vic Project in the wake of McGill’s recent loss to the Kanien’kehá:ka Kahnistensera in the Superior Court of Quebec.

“It's obvious to me that fundraising is completely inherent to the university's continued existence and excellence,” Vaillancourt stated. “But I would caution, specifically with the fundraising of the New Vic, to really read the room and fundraise in ways that are socially appropriate given the situation."

$241.8 million was raised in gifts and pledges during the 2022 fiscal yearAssociate Director of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies Lorna Mac Eachern stopped by to announce a new student engagement fund. (Maeve Reilly / The McGill Tribune)

Editor-in-Chief

Madison McLauchlan editor@mcgilltribune.com

Creative Director

Anoushka Oke aoke@mcgilltribune.com

Managing Editors

Sepideh Afshar safshar@mcgilltribune.com Matthew Molinaro mmolinaro@mcgilltribune.com Madison Edward-Wright medwardwright@mcgilltribune.com

News Editors

Lily Cason, Juliet Morrison & Ghazal Azizi news@mcgilltribune.com

Opinion Editors

Kareem Abuali, Leo Larman Brown & Valentina de la Borbolla opinion@mcgilltribune.com

Science & Technology Editors

Mayuri Maheswaran & Russel Ismael scitech@mcgilltribune.com

Student Life Editors

Abby McCormick & Mahnoor Chaudhry studentlife@mcgilltribune.com

Features Editor

Wendy Zhao features@mcgilltribune.com

Arts & Entertainment Editors

Arian Kamel & Michelle Siegel arts@mcgilltribune.com

Sports Editors

Tillie Burlock & Sarah Farnand sports@mcgilltribune.com

Design Editors

Mika Drygas & Shireen Aamir design@mcgilltribune.com

Photo Editor

Cameron Flanagan photo@mcgilltribune.com

Multimedia Editors Wendy Lin multimedia@mcgilltribune.com

Web Developers

Sneha Senthil & Oliver Warne webdev@mcgilltribune.com

Copy Editor Sarina Macleod copy@mcgilltribune.com

Social Media Editor

Taneeshaa Pradhan socialmedia@mcgilltribune.com

Business Manager

Joseph Abounohra business@mcgilltribune.com

The federal government has until Nov. 25 to appeal a Quebec Superior Court ruling that ended random traffic stops in Quebec—which the court argued is an iteration of racial profiling that disproportionately affects Black people. The case was brought to the court by Joseph-Christopher Luamba, a 22-year-old Black resident from Montreal, whom the police stopped 12 times in 18 months without cause. An appeal would threaten this vital ruling that marks a significant step forward in protecting Black people from the systemic racism and the consistent violence that is entrenched within policing.

The Superior Court’s acknowledgement of racial profiling is crucial to ensure dignity for overpoliced communities. Premier François Legault and the Quebec government have continuously denied the existence of systemic racism in the province, and the court’s ruling is a snub to these politicians. Beyond this, the ruling is in opposition to the

traditional relationship between the courts and the police. In Quebec and elsewhere, police tend to lean on the law for support and justification of their actions, and the ruling calls this practice into question. Further, the decision can be used as a precedent for similar rulings in other provinces regarding traffic stops, which remain prevalent across Canada.

Beyond the policy and legal implications of the decision, the move to end random traffic stops improves the day-to-day quality of life for Black people in Quebec. It is important to emphasize the increased comfort this will bring; Black people will be able to do everyday tasks such as going shopping or driving their kids to school without as intense a fear of being legally harassed by police officers. Despite this being an essential step forward, the ruling remains limited in its scope as it operates within the flawed framework inherent to policing.

Justice Michel Yergeau, who delivered the ruling, underlined that it applies specifically to traffic stops and that it is not an indictment of systemic racism within the entire police force. This is contradicted by the facts of policing

on the ground: Black and Indigenous people are subjected to significantly more violence and harassment by the police compared to white people, they are stripped of dignity and humiliated in police reports and media coverage, and there remains little accountability or oversight over the police. In Canada, contrary to the U.S., racial data is not collected in any province other than Ontario when police violence occurs, so it is almost impossible to accurately hold the police to account for their disproportionate targeting of people of colour. With these continued abuses by the police, we must contextualize that although ending traffic stops is a small victory, it cannot end there.

The judge’s denial of the existence of systemic racism also goes against the very nature of policing—within which systemic racism is unshakeably ingrained. Systemic racism means that even if the members of the system are not racist, outcomes will be racist because of its structure. Policing is a clear example of this. The origins of policing go back to the colonization of Indigenous peoples and the enslavement of Black people. These structures of violence

were meant to fulfill objectives of oppression, and the same structures remain to this day. As long as policing exists, it will continue to oppress marginalized people. For this reason, abolishing the police is the only road forward.

Similar to the rest of Quebec, McGill fosters an environment of systemic racism. Black and Indigenous professors remain underrepresented, while Black and Indigenous students bear the burden of educating those around them. The administration litigated aggressively against the Mohawk Mothers in an attempt to continue construction on a site potentially holding unmarked Indigenous graves. Systemic racism also is an issue among student groups. The Black Student Network (BSN) and Students for Palestinian Human Rights McGill (SPHR) are constantly mistreated by the Students’ Society of McGill University, and campus media continues to publish harmful and racist content. Systemic racism goes beyond traffic stops, and, hopefully, this ruling is the first step towards a broader recognition of the systemic racism permeating all our institutions.

during those six months, but, most importantly, I learned that having OCD is not to be taken lightly.

Shatner University Centre, 3480 McTavish, Suite 110 Montreal, QC H3A 0E7 - T: 519.546.8263

The McGill Tribune is an editorially autonomous newspaper published by the Société de Publication de la Tribune, a student society of McGill University. The content of this publication is the sole responsibil ity of The McGill Tribune and the Société de Publica tion de la Tribune, and does not necessarily represent the views of McGill University. Letters to the editor may be sent to editor@mcgilltribune.com and must include the contributor’s name, program and year and contact information. Letters should be kept under 300 words and submitted only to the Tribune. Sub missions judged by the Tribune Publication Society to be libellous, sexist, racist, homophobic or solely pro motional in nature will not be published. The Tribune reserves the right to edit all contributions. Editorials are decided upon and written by the editorial board. All other opinions are strictly those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the McGill Tribune, its editors or its staff.

Content warning: Mentions of mental illness and descriptions of intrusive thoughts and compulsions

Iwas 17 when I finally started to seek help for my obsessivecompulsive disorder (OCD).

The signs had been there for a long time, but it took me receiving a proper diagnosis to realize the scale at which it was affecting my everyday life. After six months of weekly therapy sessions, coupled with the support of my family and friends, I finally gained enough control to get my life back on track. I learned a lot about myself

OCD is a mental illness that affects roughly 350,000 people in Canada, but that’s only those who have received formal diagnoses.. Its symptoms may vary from person to person but generally involve unwanted or intrusive thoughts, which often provoke anxiety and fear, as well as ritualistic actions to help cope with said thoughts. Intrusive thoughts can manifest themselves in many ways, from fear of contamination to the inability to throw things away. For instance, I would often have anxietyprovoking thoughts about those close to me getting injured, and the only way I could shake them from my head was to perform seemingly arbitrary rituals, such as obsessively checking that the doors were locked or that the oven was turned off. If I didn’t do these rituals, I would have trouble sleeping, with thoughts of intruders or housefires racing through my mind.

I used to be embarrassed by my OCD, partially because I knew that so many people still don’t take it seriously. I have heard that a crooked picture frame is “triggering someone’s OCD” or that people who like to clean their rooms are “OCD about it” too many times. These are sentiments that I have

been hearing my whole life, at school, on the internet, everywhere. Every time I hear someone making a joke about OCD, it cuts deep, as people don’t seem to understand how horrible it truly is. I had felt the paralyzing anxiety caused by my OCD for years before I finally received help, and it is something that continues to afflict me to this day.

I would like to think that most people who say such things are not saying them out of malice, but rather out of ignorance. It is very easy to fall back on stereotypes that have been parroted for generations, but it takes effort to learn about what the condition really entails. There have been countless times where I have heard these same annoying jokes being made, and while I desperately wanted to tell people to stop, I didn’t out of embarrassment and anxiety.

Luckily, more initatives have cropped up in recent years to help educate and spread awareness about OCD and its symptoms.

International OCD Awareness Week, which takes place every year in early October, helps destigmatize OCD and provide resources for those diagnosed with the condition. The campaign is run by the International OCD Foundation, a non-profit which aims to help those dealing with OCD around

the world. They have done a lot of great work educating the public on a condition that is still widely misunderstood.

Unfortunately, there is no “cure” for these obsessivecompulsive thoughts, but there are many great resources and coping mechanisms that I am very grateful for. It is an affliction that I still deal with on a day-to-day basis, but I am in a much better place now than I was before I sought out professional help. Unfortunately, professional help is not always easily accessible and McGill’s resources for mental health support are severely lacking. From difficulties getting appointments, to staffing shortages, it can be incredibly tough for students to receive the help they need. However, there are many free, professional services, such as AMI-Quebec, that offer mental health support and counselling to those in need.

I am now at a point where I am proud to say that I am no longer ashamed or embarrassed by my OCD. It is something that I myself and many others deal with on a daily basis, and it must be taken seriously. Hopefully, with continued efforts and better education, we can finally break away from the misconceptions that continue to stigmatize people to this day.

No, you’re not “OCD” for liking things organized

First, eliminate random traffic stops. Then, abolish the police.

After a stickering campaign by Students for Palestinian Human Rights McGill (SPHR) at the end of the winter 2022 semester, McGill’s Food and Dining Services removed Sabra products from the shelves of McGill’s dining halls and cafés. However, in recent weeks, they’ve returned. Instead of toying with their merchandising to temporarily appease student groups, McGill must permanently remove Sabra products from their selection.

The Strauss Group, the parent company of Sabra which is co-owned by PepsiCo, is one of the largest food production corporations based in Israel. The group financially supports the Golani Brigade, a brutal and inhumane division of the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF). In addition to financial support, Ofra Strauss, the company’s chairwoman, has admitted to providing food and care packages to the Brigade during training and missions. The IDF is responsible for the continued ethnic cleansing and settler colonialism of Palestine through horrific violations of international law and crimes against humanity. The Golani Brigade in particular has carried out arbitrary murder campaigns, participated in

the demolition of Palestinian homes, and helped incarcerate children. The brigade played a significant role in the egregious assault on Gaza in 2008, killing around 1,400 Palestinians and wounding many more. In addition to the alienation that McGill’s hundreds of Palestinian students face from an administration that systemically ignores Israel’s war crimes, supplying blood-stained products such as those of Sabra serves as a constant reminder of McGill’s complicity. Calls to remove such products are part of a larger Boycott Divest Sanction (BDS) movement, that aims to hold Israel economically accountable for its occupation of Palestine and subsequent apartheid and colonialism. With Sabra as one among many corporations, the global movement makes calls to boycott consumer brands like Puma, L’OREAL, and Pillsbury, supported by five members of the Pillsbury family themselves. The calls for BDS were successful. Earlier this year, Pillsbury’s parent company, General Mills, divested from apartheid Israel. We are seeing worldwide that BDS works; the University of Manchester removed Sabra from its campus after a boycott campaign.

The appropriation of hummus by an Israeli-backed group serves as another example of Israel’s obsession with coopting and appropriating Palestinian culture. The Israeli promotion of falafel, hummus, and labneh without recognition of their Palestinian origins represents the overarching project to erase Palestinian culture and history. These historical and cultural deprivations complement the Israeli government’s systemic dispossession of

Palestinian land, restriction of access to water in occupied Palestine, and continual uprooting of farmland through military and settler violence.

But why does the appropriation of hummus specifically matter? In Israel’s genocidal framework, the persistence of historical Palestinian culture threatens the state’s legitimacy and independence. Therefore, cultural appropriation is just one of many tactics to suppress traces of Palestinian validity and resistance.

While settlements in the West Bank and the Gaza blockade illustrate instances of direct subjugation towards Palestinians, cultural appropriation, notably through corporate action, is far more cynical: The objective is to psychologically dominate and humiliate a people and nation by denying them not only their basic human rights but also the right to own their history and culture.

McGill has a longstanding history of profiting from Israeli apartheid in Palestine and has shown time and time again that they do not value human rights, especially when it concerns people of colour. Students, however, have begun to show up and make their positions clear. Even though it was not adopted, the Palestine Solidarity Policy was approved with a 71.1 per cent majority, a policy that held a promise to boycott all corporations complicit in settler-colonial apartheid against Palestinians, including Sabra. It is imperative that students remain active in fights against McGill’s profiteering from Israel’s violent occupation in Palestine. Complicity is violent and until Sabra is off the shelf, we’re all guilty.

E-fucking-nuf.

Harry North Staff WriterThere goes one. Oh, and another—and another. Sorry, don’t mind me, I’m just sitting on the benches outside McLennan counting the number of McGill students dressed like extroverted, self-obsessed melons.

Have you noticed McGill students have this rather psychotic fixation on dressing uniquely? Well, of course you have. The pathway through Redpath is practically a catwalk for Eva B hippie zombies to flaunt their new ‘unique’ look.

In our fight to stay original, we’re quickly led into the realm of the ridiculous. Wacky adornments, with little actual value, become the new norm. And each week there’s a new one: Oversized jackets, because who needs clothes that actually fit? Silly hats with fur on the outside, because the warmth of fur on the inside is so cliche. Woolly leg warmers? These are basically woolly sweaters for your calves. And before you butt in—no, this phase will age like milk.

Without question, though, the worst I’ve heard was recently in Redpath Café: “T-shirts are the new dresses.” Yep, that will do me. Pour me a drink and bash me over the head with the bottle.

First off: No, they’re not. Because if they were, they’d be, well, they’d just be dresses, wouldn’t they? And second: If t-shirts are dresses today, what’s next? Skirts as t-shirts tomorrow? Socks as earmuffs the week after? Enough.

This obsession with dressing uniquely has all gone a bit HBO, so we need to pack it up. We need a uniform.

What we choose to wear is not just a reflection of who we are, but who we think we are. So, judging by our outfits, we think we’re fucking idiots.

Look, I sympathize with you. I do. The only thing more frustrating than trying to dress uniquely and looking like a total twit is purposefully dressing like one, and then arriving on campus only to find someone else dressed in the exact same twitty outfit. And I admit, I have my moments of inspiration, too. Some days I might even dress like I’m actually happy. But it’s so much effort.

A school unsform solves these problems. No longer will we have to spend hours in the morning deciding which hat goes with our coat. We won’t have to worry about our parents raising an eyebrow at our latest ‘phase.’ It will make McGill students even more visible to the local community, so our good deeds don’t go unrecognized—if there are any, of course.

School uniforms will let us focus on the more important issues. Instead of showing our uniqueness through accessories, we can show it by distinguishing ourselves through standardized exams. We will also have more time to raise the issues that matter outside of the classroom. God forbid, we could start voicing our opinions and participating in student and local elections!

It isn’t just about what a school uniform does directly, but also what it represents. Was it not the great Gandhi who said, “College kids in Canada really ought to have a uniform. They’re 7,500 miles away, and they’re still pissing me off!”

By enforcing conformity, we can take our distracting narcissistic traits out of the equation, at least for now. At least until we stop thinking our calves need sweaters.

Why do you personally want a uniform? I’m offended by vibrant colors.

“But my own clothes are more comfortable!!?”

Do you think Margaret Thatcher wore sweatpants?

What’s in it for McGill?

A profitable uniform shop. The profits can be reinvested into our community, like buying all the Deans a Porsche so they can get to school faster.

What would be the new uniform?

I’m open to all ideas. Maybe something grey. Pitch your ideas!

How much would this new uniform cost?

If you shit money, you should be fine.

A study has shown that a uniform policy decreases tardiness and improves students’ grades. (McGill University).

As recently as 2021, Sabra has issued recalls on their products for salmonella and listeria contami nation. (J. Sellers Hill / The Harvard Crimson)In the summer of 1950, Lida Moser set out from New York City on a journey to capture the spirit of Quebec through photographs. She was a single woman travelling with three men: Ethnologist Luc Lacourcière, folklorist Félix-Antoine Savard, and Paul Gouin, cultural advisor to Pre mier Maurice Duplessis. She did not speak a word of French.

Today, her corpus of over a thou sand photos continues to resonate with Quebecois and non-Quebecois people alike. They have been carefully pre served in the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ) and exhibited at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec. Now, they live on vividly in the animated short film Lida Moser Photographer: Odyssey in Black and White, produced by Acad emy-Award nominated filmmaker Joyce Borenstein.

The McGill Tribune sat down with Borenstein and former McGill professor Norman Cornett to discuss the film and the lasting impact of Lida Moser’s photographs.

“What started me on this quest

was seeing her photographs. They just bowled me over, they were exquisite. They recalled my idyllic summers as a child,” Borenstein said. “My par ents rented and then bought a little old schoolhouse in the middle of the farm land of Quebec, in the Laurentians. We played with our neighbours, who were francophone farming kids. We didn’t need language at the time [….] We got along beautifully, and summers were my favourite times in my childhood.”

Currents of profound understand ing run through the film. Borenstein was born in Montreal to an immigrant, anglophone, Jewish family, and relates to Moser as a woman persisting in a patriarchal world. She explores the complexities of feelings of otherness with lyrical empathy, by placing her self in Lida Moser’s shoes.

“I retraced her steps, I did her journey two and a half times,” Boren stein said. “It came alive, and I fell in love.”

Professor Norman Cornett, also a Montrealer, was likewise captured by Moser’s photographs and Boren stein’s film. Earlier this fall, Cornett discussed the film in depth with Bo renstein as part of a series of video dialogues.

“What intrigues me in Lida

Moser Photographer as a religious studies scholar is, particularly as it re lates to [Bill] 96 and nationalism, it’s as though through the animated docu

dren growing up, playing with kit tens, and people sitting outside, work ing with tools. What, then, shapes La Belle Province are not majestic

leaning, socially conscious artists [....] They want to tell the people’s stories, not the bankers’ stories [...] they want to tell the untold stories,” Cornett said. “To what extent are we doing justice to the history of French Canada, to the history of Quebec, if we’re only look ing at it through the lens of those that are bigger than life?”

The film’s focus on everyday life crucially presents a rare and acces sible ethnographic picture of Quebec in the 20th century. The language-less nature of photography and animation makes them boundary-breaking me diums to tell the story of a province whose identity exists entrenched in the French language.

mentary, we can see Quebec, its his tory, its people, its language, through another lens, in another light,” Cornett said.

The film’s Quebec is not the Quebec of postcards or brochures. Lida Moser’s photos do not depict eminent figures, grand buildings, or familiar landmarks. They show chil

On what grounds do we de scribe music that breaks with Western traditions? Does the simple label “world music” suffice? Unsurprisingly, this term was not popularized by so-called world musicians. Rath er, like much of the language we use to describe music, it was the creation of profit-minded record label executives. In 1987, indus try tycoons were looking to capi talize on the success of Paul Si mon’s South African-influenced Graceland to start selling more music by African artists to West ern audiences. They settled on “world music” as a broad mar keting term to denote music not originating from Europe or North America.

In many ways, the top-down nature of this term’s inception and its formulation in the absence of any actual musicians is reflective of its problems. World music casts an otherness upon the music it en compasses, demarcating it solely by the fact that it’s not Western, rather than what it sounds like or how it was composed. It’s clear to any listener that the Brazilian

Tropicália music of Caetano Ve loso bears no more, and arguably much less, relation to North-Indi an classical music by Ravi Shan

eign art and culture as less highbrow or unsophisticated. This has pervaded the way we engage with art throughout history, both in

monuments, but images of everyday life. The resulting photographs relate to outsiders in Quebec and abroad in their sheer authenticity.

For Cornett, this approach, grounded in everyday occurrences, captures Moser’s essence.

“Lida Moser comes from that milieu, that ambience, of Jewish, left-

“Somehow art gets through [...] no matter the language,” Cornett said. “Art transcends language, art tran scends ethnicity, art transcends iden tity, art transcends the boundaries, the barriers, between us. And that is the beauty of Lida Moser Photographer She doesn’t speak a word, and yet we hear her loud and clear.”

Lida Moser Photographer: Odys sey in Black and White is currently in distribution, but is available to McGill students as a DVD via interlibrary loan.

kar than it does to Western pop or rock music. To lump the two artists under one bracket ensures that the designation of “world music” is defined by its proxim ity to our narrow conception of Western music. This reinforces a Western hegemony that casts for

terms of how it is marketed and how consumers perceive it. Such a characterization fails to grant non-Western artists the individuality they deserve. When it comes to Western artists, enter tainment media is more than will ing to hyper-taxonomize, creating

ever-more specific genre labels to describe the next progressivemetal-influenced mathcore band or post-punk revival act. Pigeon holing artists into overly narrow labels can itself be unhelpful, but this tendency of music journal ists highlights that they can be specific in their descriptions of artists when they actually make an effort. Identifying the specific genre of a foreign artist operates as a basic courtesy that would crucially enable such artists to forge their own musical identity distinct from their nationality.

Besides the lack of respect the term “world music” affords artists, the designation lacks any utility for listeners. At their best, genre labels help differentiate be tween different kinds of music, describing how an artist sounds or the movement they belong to so that listeners can gravitate to wards music they are more likely to enjoy. A broad-strokes term like “world music” fails because it reveals so little about the fun damental basis of music: How it sounds. What types of instruments does an artist compose with? What kinds of harmonies do they employ? What lyrical themes do they explore? Labelling an album

as world music does nothing to answer any of these questions.

The perniciousness of this term is symptomatic of one of Western music media’s major fail ures: It can’t challenge the prem ises on which its viewpoints rest. Panels for music awards, such as the Grammys, regularly shoehorn Black artists’ musical achieve ments into the category of rap, or until recently, “urban” music, in spite of music often not fit ting into those characterizations. Meanwhile, the Golden Globes’ critic panel decided to place Mi nari (2020) into its foreign film category due to its dialogue being predominantly in Korean, despite the American-produced film’s central tenet being the promise of the American Dream to U.S. im migrants. These examples demon strate how the merits of the works of non-Western artists and people of colour are routinely conceived of through a white-centric view point.

Ultimately, what “world music” gets wrong is that, for its artists, world music is just music. Labelling music in binary terms based on its Western or non-West ern origin is not just disrespect ful: It’s bad music journalism.

Why it’s time to move on from this lazy labelJoyce Borenstein’s 1992 Academy Award-nominated film The Colours of my Father: A Portrait of Sam Borenstein is available online through the McGill University Library. (Cameron Flanagan / The McGill Tribune)

McGill University bears the name of its founder James McGill, but this honor ific title was a condition tied to James’s large donations which were used to estab lish the institution. His gift, however, cannot be isolated from the colonial violence which produced it. He was only able to formalize the higher education system in Canada—albeit for white men only—by exploiting and enslav ing Black and Indigenous people on stolen land. In addition to casting light on the colonial structures of Canadian universities, McGill’s depraved founding exemplifies an issue that lingers today: The power that donors can exert over campuses.

Though public funding constitutes the majority of the total revenue for most Canadian univer sities, the decline in government spending on postsecondary education along with campus es’ increasing operational costs have forced universities to pursue other sources of income.

In the 2019-2020 year, more than 70 per cent of the total college revenue was publicly fund ed in most Canadian provinces and territories, including Quebec. Yet, total public investment in universities has been on a gradual decline across Canada since 2008-2009, decreasing from 67.0 per cent to 54.7 per cent in 20192020. Spikes in tuition fees, reliance on inter national students, and private donations are compensating for this decline. At McGill, the revenue generated by donations and invest ment interest on endowed gifts for the 2021 fiscal year was approximately $170.2 million of its total revenue of $1.47 billion.

Derek Cassoff, managing director of com munications at McGill’s University Ad vancement (UA) office, explained that the university accepts two kinds of donations: Direct-spend gifts that are spent at once, and endowed gifts that establish an investment fund and exist in perpetuity.

“We have gifts at the university that go back to the 19th century donors [...] 150 years ago, that are still [...] operating today because of [the McGill Endowment Fund],” Cassoff said. “The university’s endowment right now is about $1.8 billion, which is pretty high by Canadian standards, [and] just shows the level of generosity that McGill donors have shown over time.”

Yet, as donations compose more and more of universities’ funding landscape, concerns grow for how the interests of third-party funding can cross the line into academic and campus life.

In 2020, the University of Toronto (UofT) re scinded a directorship offer to Valentina Aza rova, a human-rights lawyer and scholar. The withdrawal had been prompted by a phone call from a tax judge and major donor to the Faculty of Law named David Spiro. In it, Spiro

By Ghazal Azizi, News Editorhad expressed apprehension about Azaro va’s recruitment due to her previous papers on the Israeli occupation of Palestine. Spiro’s controversial intervention in the university’s hiring decision led the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) to censure the UofT administration in April 2021, a rare and last-resort sanction in which academic staff are asked to decline appointments, speaking engagements, and awards. The censure suc cessfully pressured the university to re-offer the position to Azarova, who declined it the second time around. Experts attributed the infringement of academic freedom at UofT to a reliance on donations in the wake of public funding cuts, arguing that this financial model undermines campus autonomy. Azarova’s mistreatment at UofT is not an isolat ed story. Jennifer Berdahl joined the Universi ty of British Columbia (UBC)’s Sauder School of Business in 2014 as the Montalbano Pro fessor of Leadership Studies, a position ded icated to gender equality in the workplace. When Arvind Gupta, UBC’s president and vice-chancellor, resigned only a year into his five-year contract, Berdahl shared a blog post theorizing that Gupta’s sudden departure was due to the toxic “masculinity contest” at the university. John Montalbano, the former chair at UBC’s Board of Governors (BoG), whose $2 million donation funded Sauder’s Montalbano Centre for Responsible Leadership Develop ment and created Berdahl’s professorship, was infuriated by Berdahl’s post.

“He basically eventually called me up at home on a Sunday morning and just really chewed me a new one and told me my reputation was shit now and [...] I would lose my funding,” Berdahl said in an interview with the Tribune “Later that night, he sent an Associate Dean af ter me [who] sat me down, and basically told me that I better shut up.”

The UBC administration took away funding for Berdahl’s profes sorship, removed her from all committees, and debili tated her from fulfilling her positional duties, research, and outreach.

“A bunch of women in Vancouver who were executives and high up in [...] industry had been on this Board of Advisors for me. They all stopped talking to me and that board got dissolved because they were Montalbano’s connections and friends. Basically, they literally took away my position and the support behind it.”

Berdahl took to her blog once more to publi cize this infringement on her academic free

dom. “They were going to kill me quietly or they could kill me publicly, and I chose the public killing,” she told me. Following the post, the UBC Faculty Association began an 18-months-long grievance process, after which Berdahl recovered half of her fund ing. Former British Columbia Supreme Court Justice Lynn Smith conducted an investiga tion that concluded “Dr. Berdahl reasonably felt reprimanded, silenced and isolated” by the UBC administrators, though Montalbano was not found guilty of violating any of UBC’s policies. While Montalbano stepped down as the chair of the university’s BoG, the scan dal shows the murky waters of undue influ ence that can accompany donations. Berdahl claims that a fundraising employee revealed to her in confidence that there was an implic it understanding between the university and Montalbano that his donation would grant him the BoG chair position.

“[As] our public universities become in creasingly reliant upon donors for funding, donors are playing an outsized role in influ encing the direction of universities in ways that they shouldn’t,” Berdahl said. “[T]hat’s really threatening the current state of uni versities today.”

The rivalry between UofT, UBC, and McGill extends beyond rankings; violating aca demic freedom seems to be another sport for Canada’s top universities. In 2017, An drew Potter stepped down as the director of the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada (MISC) three days after publishing an essay in which he characterized Quebec as an “al most pathologically alienated and low-trust society.” Six hundred eighty eight pages of internal emails revealed that Potter was pres sured to step down by former Principal and Vice-Chancellor Suzanne Fortier, following public backlash and donors threatening to cut funding to the institute. Andrew Potter declined the Tribune’s re quest for a comment on the matter.

McGill never admitted to infringing on Potter’s academic freedom.

Fortier insisted that ac ademics in managerial and administrative roles at the university should not enjoy the same level of academic freedom as academics outside such po sitions. Yet, a report by the CAUT concluded that the university had violated the McGill Statement of Academic Freedom and challenged Fortier’s claim, which has since been known as the Fortier Doctrine and was in fact the same argument that UofT

directorship offer.

Berdahl finds that public underfunding of universities has created a corporate culture of prioritizing fundraising over academic val ues.

“If you think about people’s position, [their] ability to please donors and raise money is a huge part of [their] evaluation as a lead er now, right? [...] And in fact, the Associate Dean, who was probably most invoked in my violating my academic freedom, is now the Dean. He was basically rewarded for violat ing my academic freedom and maybe doing other things”

Renee Sieber, the President of the McGill Asso ciation of University Teachers (MAUT), also finds that there is a culture at universities to solicit do nors for donations that are rarely unconditional. “[University Advancements] are very protec tive of donors, who they nurture throughout the lifetime of the donor,” Sieber told the Tribune “McGill spends considerable time trying to fa cilitate that loyalty from people who eventually become donors. The general public might see it as, ‘hello, wealthy person out there, we’re go ing to go after you for money.’ It usually is, ‘you have an existing connection to the university, because you went there, you sent your kids there.’ And that loyalty is nurtured over time.” McGill, too, admits that there are “ongoing conversations between the university, its fundraising team, and [...] loyal donors,” ac cording to Cassoff, who also claims gift ne gotiations can take up to a decade at times. Universities turn increasingly to grooming donors as an unfortunate survival mecha nism. Treating campuses as playgrounds for capitalist exchanges is a quicksand that threatens the very existence and purpose of higher education. David Robinson, exec utive director at the CAUT, argues that the influx of specific donations creates “a dis tortion within academic priorities,” where certain programs or initiatives receive more resources than others depending on the de sires and interests of private donors. “[D]onors are going to be interested in cer tain kinds of programs that may not be the academically most interesting programs, but they’re going to be interested in things that they have a personal interest in, or that [are] aligned with their business interests, [or] profile,” Robinson told the Tribune “We’re going to see lots of funding for the kind of [...] corporate responsibility issues or things that are of interest to the corporate world, but we’re not going to see a lot of do nations going to the [...] study of child pover ty in Canada [...], to [...] theoretical physics.” McGill’s income from endowed gifts must be used for the specific purposes laid out in the do nation contract. Donations can, therefore, dictate the future of a university for decades. Andrew Kirk, a professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer science, served as Interim Dean at the Faculty of Engineering from 2011 to 2013 and was privy to this oft-camouflaged force. Ac cording to Kirk, there were century-old legacy

donations at the faculty that funded out-of-date research and had to be renegotiated with the successors of the late donor.

“You’ve really got to steer donors away from locking us into doing something that seems great right now, but it’s so specific that it’s not going to be useful in the future,” Kirk said in an interview with the Tribune

“[We] want to make sure that donations have got as much flex ibility as possible so that they can be used to bene fit the university for many years to come.”

While external pressures and in terventions in univer sity affairs grow with private donations, a larger threat ensues when administrations internalize sycophancy. Rob inson believes that universities tend to uncon sciously appease donors following large sums of donations out of fear that offending them will jeopardize future partnerships and fundrais ing.

“If a pharmaceutical company had given mon ey to a health institute and the health institute wanted to put on a series of lectures talking about the harms caused by certain pharma ceutical drugs, would that be something that people might be shy to pursue? It’s certainly possible. And I think that’s more of the kind of subtle influence that the donors have,” Robin son told the Tribune

Robinson’s example is not hypothetical. Al most two decades before the Azarova scan dal, UofT had similarly revoked a job offer to psychiatry professor David Healy, who ques tioned the safety of Prozac and the pharma ceutical company Eli Lilly, a corporate donor to the university. In addition, a Global News investigation revealed that the pharmaceuti cal industry alone invests millions of dollars each year in Canadian universities to help shape medical education. At McGill, for in stance, pharmaceutical company Merck & Co Inc. donated $4 million to the Faculty of Med icine and Health Sciences in 2013 as part of its five-year project to inject $100 million into biopharmaceutical research and develop ment in Quebec. Environmentally extractive companies have also crept into the universi ty’s administrative skeleton. The Faculty of Engineering actively partners with Suncor Energy Foundation, a fossil fuel company, and the two mining companies Rio Tinto and ArcelorMittal Mining Canada Gross Profit (G.P.). McGill’s BoG hosts members with di rect ties to various corporations, such as the pharmaceutical company Knight Therapeu tics Inc., or Petro-Canada. As private corpo rate donors pump money into the university, McGill reciprocates with a sense of duty to

protect the interests of its financial supporters over the faculty and students—the neglected beating hearts of the campus.

The administration’s repeated refusal to divest from fossil fuel companies, despite student and faculty pleas, is a telling example. Greg Mik kelson, a former professor in the School of Environment and the Department of Philosophy, who resigned when the BoG opposed his divestment motion, finds McGill’s obstinacy to be an extension of its priori ties.

“Back when the clique who run the McGill Board [of Governors] were try ing to justify their second refusal to divest from fossil fuel, they [demonstrated] what seemed to be great er loyalty to other wealthy do nors (i.e., their own peers) than to McGill students, faculty, staff, Quebec society, or even Canadian society, let alone the larger biotic community,” Mikkelson wrote in a statement to the Tribune

Divest McGill, a climate activism group on campus, also claims that “if your project doesn’t fit the BoG’s agenda, it will not go through.”

Yet, Divest has identified a way to circumvent the university’s favouring of money over stu dent and faculty democracy.

“One interesting strategy taken by the folks at Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard was to collect dona tions from alumni in Harvard’s stead that they would then give to Harvard only if they divest ed,” Divest McGill wrote to the Tribune. “This is an avenue that could be taken at McGill too, and if they still refuse to divest then that money could become a ready-made seed fund for re investment projects.”

Not only the university’s name, but the titles of several buildings on campus bear the re minder of wealth too often tied to private motivations. Realizing the depths of money’s entrenched and corrupt role in our cam puses may evoke demoralizing emotions of helplessness. Eliminating unwelcome donor influence, however, is an effort not without hope. Leverage campaigns like Divest’s may help achieve short-term results, but cannot solve the root issue. Capitalist dynamics of competition for funds have taken over the university. Increased public funding best serves as a weapon to safeguard academic freedom and student democracy, especially in Quebec, where underfunding universities has been a persistent problem. If the fragile financial state of universities continues due to government negligence, and the university continues to prioritize capital at the expense of students, private interests will monopolize campuses to the point where they will cease to exist as public-serving, intellectual entities.

Design by Shireen Aamir, Design Editor

As announced earlier this month, Netflix has extend ed its new Monster anthol ogy series past its first installment, The Jeffrey Dahmer Story, which was released on Sept. 21. With at least two more projects in the works, the creators hope to follow the sto ries of “other monstrous figures who have impacted society.”

The Jeffrey Dahmer Story, coming from the minds of Ryan Murphy and Ian Brennan, has emerged as one of Netflix’s most commercially successful TV shows. Within 28 days of its release, it became the streaming platform’s second-most-watched English-lan guage series of all time. The fiction al re-enactment explores the psyche of American serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer (Evan Peters), who com mitted numerous horrific murders between 1978 and 1991—all of the victims were men and adolescent boys, most of whom were people of colour.

Despite its high viewership, its release was riddled with controver sy. From initially being categorized under the LGBTQ+ tag on Netflix to more general criticism regard ing the show’s quality, the show has been under continuous scru tiny. Yet, perhaps the largest cloud

hanging above its conception is the outrage expressed by the families of Dahmer’s victims.

Rita Isabell, sister of victim Errol Lindsey, wrote a personal essay for Insider to express her anger regarding her portrayal in one of its episodes despite the show’s producers never having contacted her. She describes the experience of watching the events of her life occur on TV, writing that “it felt like reliv ing it all over again.” She goes on to denounce the lack of compensation provided to the victims’ families, stating that “it’s sad they’re making money off of this tragedy. That’s just greed.” In the adaptation of this history, Netflix asserts its ownership of the victims’ experiences.

Two more seasons, with two more serial killers, will bring about

two more groups of people directly impacted by real-life events and potentially retraumatized by a tele vision portrayal. Whether Netflix plans to ask permission or provide compensation is still unclear. But even if they do, the re-creation of serial killers to be consumed as en tertainment presents a multitude of ethical concerns.

Following the release of Mon ster, there was an increased romanti cization on social media of Dahmer himself, as viewers sympathized with Peters’ troubled character and conflated Murphy’s creative inter pretation with reality. Not only that, but the trend of dressing up as Jef frey Dahmer for Halloween circu lated online. Costumes relating to him were eventually banned from various sites, such as eBay, due to

subsequent backlash. Several Mil waukee bars, where Dahmer met many of his victims, announced that they would deny entrance to those dressing up as him on Halloween night.

The danger of portraying se rial killers on-screen is the inability to resist the inherent creative urge to immerse the viewers into their minds. It will inspire the viewers to create motive, to charitably explain their actions, and ultimately glorify their image. The moment they are presented under the guise of fiction, and especially when played by fa miliar, attractive actors, they enter the realm of pop culture—a space that, in most instances, cannot take itself seriously and cannot escape a profit-oriented mindset. Even call ing it a Story reduces its material ity—it’s a story that is not to be told by just anyone. While there may be many factors contributing to the commercial success of such adapta tions, one cannot argue against the morbid fascination viewers may have with such dark stories—a fas cination Netflix is well aware of and seems intent on exploiting.

As the next two seasons’ pro duction of Netflix’s Monster anthol ogy series begins, viewers should keep in mind what is at stake: Those who are not compensated, those who are retraumatized, and those who are glorified.

McGill’s Department of English Drama is proud to present its performance of Alistair McDowell’s 2014 play Pomona, which tells the story of an adolescent who is drawn into the criminal underworld when her sister goes missing.

Dates: November 23-25th, November 30th, December 1-2nd.

Moyse Hall Theatre, 853 Sherbrooke St W, Montreal, QC H3A 0G5

Tickets are $15 and available at https://moysehall. tuxedobillet.com/.

The 11-day LGBTQ+ film festival returns for its 35th edition, featuring award-winning local and internationally produced films.

Dates: November 17th - 27th

Tickets range from $6 for short films to $13.50 and are and available at https://www.image-nation.org/en/festival2022-en/.

In person screenings take place at cinemas across Montreal, while some films are also being screened online.

Visit the MMFA where the work Contre-espace by multidisciplinary artist Sabrina Ratté is projected onto the facade of the museum every evening.

Dates: Every evening until November 27th, 2022, dusk to 11pm.

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1380 Sherbrooke St W, Montreal, QC H3G 1J5 Free event.

L’Oasis Musicale: free live music

Listen to local musicians perform classical, folk and jazz in the serene setting of a heritage church at this free weekly concert series.

Date: Saturdays, 4pm.

Christ Church Cathedral, 635 Sainte-Catherine Street West, Montréal, QC Free event.

For the first time in two years, McGill’s Department of Eng lish Drama & Theatre will be welcoming a full house back into Moyse Hall when its production of Pomona by Alistair McDowall opens on Nov. 23. Originally commissioned for The Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama in 2014, the play follows a young woman named Ollie as she des perately searches for her missing sis ter. A thrilling, surreal quest unfolds as she makes her way into a dark criminal underworld where nothing is as it ap pears.

Director Sean Carney, an asso ciate professor in the English Depart ment’s Drama & Theatre and Cultural Studies streams, was drawn to the play for its intriguing plot and contempo rary appeal. Notably, this is not the first time that McGill has produced Po mona. In March of 2020, Carney and Moyse Hall’s production team were amidst rehearsals for the play when the COVID-19 pandemic struck, shutter ing theatres around the world. While memories of that lost production are bittersweet, Carney insisted on making

this year’s Pomona a fresh start.

“I felt that it was important not to just revive that production,” Carney said in an interview with The McGill Tribune. “So it was all working pretty much from scratch.”

This iteration of Pomona took on a whole new cast, crew, production concept, and design. Rehearsals began in September 2022 with a cast of five undergraduate students, whose majors range from physics and mathematics to economics and theatre.

In rehearsing the show, Carney was excited by the learning opportuni ties that Pomona presents to its student cast. The majority of the play’s scenes include only two or three characters of its small ensemble, allowing the actors to focus on detailed character work and the complex dynamics between them and their scene partners. Given the play’s dark subject matter, Carney also felt strongly about equipping the cast with methods to preserve both their physical and psychological safety while performing.

“I don’t ascribe to the idea that you have to put yourself at risk when you’re acting in a play,” Carney said.

Instead, he encourages the actors to pursue a more distanced approach:

Each performer is instructed to look for an “as if” experience that is emo tionally close to a real experience they may have, allowing them to access the intended emotions without feeling overwhelmed or unsafe during a dif ficult scene.

Outside the rehearsal hall, stu dents from ENGL 368: Stage Scenery and Lighting were tasked with devel oping the world of Pomona through its design elements. Students expressed which areas of technical theatre inter