10 minute read

the Old Home

Ashkenazi Jewish here in Montreal Brown, Opinion Editor

identity side quests, howromanticization and were perhaps didn’t know who I was trygrandmother wasn’t ethnididn’t even speak Polish; she Yiddish. More importantly, my places for a reason. Although are remembered, the stohorrific; both sides of my due to pogroms-–antisemitic hundreds of thousands of Jews were deeply affected by upon them by the Nazi regime, his conception of origin. Germany in 1938 after being Nuremberg laws,” Avishai said. Poland, his entire family was person except for two cousins his siblings, grandparents, everyone left under really terhappened was so bad that I connection to these counthem but not in a positive quickly found its way to Zaidy tell me stories to feed this had. The stories he told, about Eastern Europe and his of them were actually about Montreal—in an intensely vibrant community in the first half of the numbering over 100,000 people. about how on one of his first they were up until 5 a.m.— they went to either St. (I can’t remember which), the bagels for the day. absurdity of being recruited a deli to the YMHA’s basbecause he was 6-foot-8. He of an intimidation factor. dynamics of the different JewByng, located on St. Urbain poorer first-generation Jews Academy—where Zaidy Ell went— wealthier multi-generational older, he mentioned in passhe dated Leonard Cohen’s months. stories, I started to feel the as I did about the Old Home much. I imagined Montreal as Jewish life and folklore. alone in speaking of Monwith Ashkenazi Jewish culand executive director of Montreal, described how the Laurent Boulevard, mainly the held a thriving Yiddish culture were over 90 synagogues in own society that was Yiddish-speak - ing, strongly and tightly knit. Yiddish had become the third-most-spoken language in the city after French and English and basically stayed that way until the 1950s,” Moses explained. “There was also a publishing house [a part of Canada’s leading Yiddish newspaper, Der Keneder Adler], so Yiddish writers living in Montreal could publish their books here, and they would be exported back to Europe. So in the 1920s and 30s, there were Yiddish poets from Montreal being read in Warsaw, Kyiv, and other parts of Eastern Europe.”

Advertisement

My mom was also born in Montreal, in the CôtesDes-Neiges area, but left with her family along with thousands of other Jews during the 60s and 70s in search of better opportunities. The growing Quebec nationalist movement left the mostly-anglophone community feeling ostracized. Even to this day, there is resentment in my family regarding how they were forced to feel alien in the province and city that was their home.

“For many it felt like the rug was pulled out from underneath them,” Moses said. “Of course it’s not at all the same, but the shock of a political movement tied to an ethnicity and language that was calling for major, major changes, came within a generation of the Holocaust or other upheavals in Europe [….] But that’s not necessarily the main reason most people left, the other reason was economic. If you didn’t speak French that well, the possibilities for you quickly became much fewer.”

The month before I was set to leave Toronto to study at McGill, Zaidy Ell passed away.

He was old when he passed and had prepared us for the moment, so it wasn’t a shock or a tragedy. But being in Montreal—existing in the same city as he did at the same age—it breaks my heart that I can no longer share my life with him, and that he can’t either.

I know that he would have re-lived his youth through me as I told him about my days in his city. He would have recounted the memories that he had walking down “St. Lawrence Boulevard” after I told him about my own adventures, or he would have recommended to me a restaurant that has long been closed down.

But, at the same time, the city makes me feel connected to him and to my ancestors.

I’m less than 10 minutes away from Baron Byng— the history of which I know intimately because of Zaidy Ell. I’m also a short walk from St. Viateur and Fairmount bagel. I can’t remember which one the story is from—and that makes me a little sad—but, regardless, I can taste the same bagels that Bubby Shirl and Zaidy Ell had at 5 a.m. over 60 years ago. Or, how every day I go to campus, I walk down St. Laurent, a street he told me so much about and traditionally the beating heart of Jewish life in Montreal.

There’s also a tinge of disappointment about this return to my imagined Old Home. It’s lovely to be here, surrounded by so much personal family history, but it’s not this magical existence that I always imagined it would be. My days here feel mostly the same as they do back home— not some intrinsically meaningful experience.

Despite the large migration out of the city along with a post-War suburbanization out of the St. Laurent core, Jewish life still remains in Montreal.

Ben Wexler, U2 Arts, grew up in the city and attended Jewish schools throughout his childhood. He highlighted the increased diversity between Ashkenazim and Jews mainly from North Africa, called Sephardim

“There’s a depth of diversity and experience here that’s pretty great,” Ben explained. “Language figures into it a good bit, with Jews in Montreal being outside the established anglo community to some extent and outside the franco community, and then within the Jewish community there’s also this linguistic divide between Ashkenazim and Sephardim.”

Near the end of our conversation, I tried to press Ben to answer whether the Jewish community still retains the romanticized, Yiddish-speaking character of my grandfather’s youth that I felt was truly authentic to Montreal—that the community had the same reverence for the past and viewed the city the same way I did. Ben, however, didn’t conceive of it that way.

“I don’t think you can speak about one Montreal Jewish community. I also don’t think you can speak of one Montreal community,” Ben said. “At a certain point, that search for authenticity can feel like some pastiche of Yiddishkayt [Ashkenazi culture] [....] I think you’ve got to approach the Jewish community in Montreal as it is, and it’s not going to be this sexy, disreputable Yiddish world. It’s a different world now, and that’s it.”

My conversation with Ben punctuated the struggle I was having throughout this journey. So much of my identity is tied to my constructed image of these places—that life there was somehow more beautiful. I wanted the Montreal community in the present day to fulfill that longing—but, really, it’s just a place. I can’t help but realize that Zaidy Ell’s Montreal, and even Eastern Europe were the same—just places. Of course they all carry culture and community, and it’s a tragedy that some of it was destroyed or simply no longer exists. But the people there were just living their lives; it wasn’t some magical existence.

In the same sense, returning to Montreal, my Old Home, was not this transcendent experience that brought me my long-sought clarity about who I am. Although it’s certainly nice to be here, and Montreal is a lovely city, I don’t feel like I’m living the life of Zaidy Ell or my ancestors, and I don’t feel like I’ve returned home Montreal just feels like a place to me, and maybe that’s a good enough place to start.

Design by Drea Garcia Avila, Design Editor

Joesef’s ‘Permanent Damage’ delves into the messiness of breakups

With sincere lyrics and a lo-fi vibe, Joesef delivers a strong debut album

Titouan

Le Ster

Contributor

On Jan. 13, Joesef released his debut album, Permanent Damage, a soulful and intimate ode to his chaotic romantic relationships. The ominous title describes the indelible mark that love and subsequent heartbreak can leave on a person. A honeysoaked voice and confessional, explorative lyrics characterize the Scottish singer-songwriter, who moved to London in 2020, as an emerging figure in the alt-pop genre.

Throughout the album’s 13 tracks, Joesef walks his listeners through the feelings of losing and being lost, hurting and being hurt, and the residual love that lingers even when it should be gone. In “Borderline,” the instrumental quiets down, giving the stage to a close-mic narrative about meeting the right person at the wrong time. The funky and upbeat mood of “Didn’t Know How (to Love You)” accurately conveys the feeling of not caring anymore. And “Joe”’s lively and uplifting rhythm contrasts with the subject matter of a bad relationship with oneself.

The queer artist presents his brutally honest and unapologetic lyrics as a result of his upbringing in Glasgow’s East End, which he once described as “a rough area where what you see is what you get.” The influence of his hometown appears in “East End Coast,” which presents Glasgow as a comforting place through a melody both melancholic and uplifting.

Sonically, Permanent Damage evolves in a soul and indie pop universe. Joesef’s falsetto allows for a light breeze of airiness on themes that could easily drag you down. Alternatively, his full voice brings the listener through the tumultuousness of love with smooth delivery grounded by raw lyrics.

The 27-year-old singer emerged four years ago with the debut EP Play Me Something Nice, followed by Does It Make You Feel Good? in 2020, both exploring the theme of deep longing. With this debut album, Joesef continues digging into his emotions— especially the ones related to breakups—for inspiration. His continued authenticity and heartinfused songs are an undeniable reason for Joesef’s solid fan following, who will be the first to experience this album live on stage during his European tour starting in March.

Permanent Damage is available to stream on all platforms.

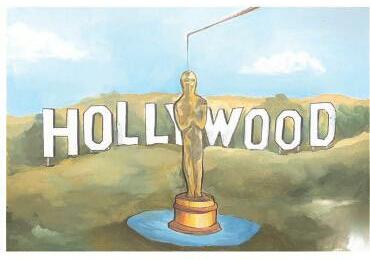

Celebrating Black Hollywood—even if the Oscars won’t

Turning the lights, camera, and action to awards shows that honour Black performances

Simi Ogunsola Contributor

Continued from page 1.

Out of their nearly 100 years of running, this is the 83rd time that there are no Black actors being featured in best actor nominations. There are no women directors at all—and no Black women directors have ever been—nominated in the director’s category. The Woman King, Till and Nope all grossed millions of dollars at the box office and boast Rotten Tomatoes scores above 80 per cent; yet, none of them garnered a single nomination.

As I clicked through article after article about Oscar nominations, my heart was dropping. Each one gave a different angle on why Black artists were being shut out of the Academy Awards this season. Some people were mad, railing that even after the awareness spread in 2015 and inclusionary efforts made by award institutions, nothing had really changed. Some people were more jaded, explaining that studios were simply out to do whatever would make them the most money. My mood sank deeper and deeper until I came across an article in the LA Times. The author, Shawn Edwards, argued that yes, so many awards shows and awards institutions ignore Black talent, but there are so many smaller organizations that uplift it.

During this year’s Black History Month, the idea of making this a time to celebrate Black achievement and experiences through Black Joy Month has gained popularity. In that spirit, this isn’t an article lamenting the lack of appropriate recognition for Black artists in Hollywood––this is one that celebrates the institutions that uplift them. Supporting those ones, bringing attention and renown to them is a way to make Black voices heard, Black performances celebrated, and Black experiences told. Don’t let your appreciation end with these awards ceremonies listed here—there are so many more rejoicing in Black talent onscreen.

Toronto Black Film Festival

In their own words, “the Toronto Black Film Festival is about discovery.” The annual festival occurs every February and seeks to create a space for people to debate cultural, social, and socio-economic topics specific to Black Canadians. The festival hosts a mixture of live musical performances, film screenings, talks from industry professionals, and networking events. They celebrate a milestone anniversary this year—10 years of celebrating diversity within Black communities. It was just a decade ago that this festival was created by its sister festival that happens right here in Montreal.

Montreal International Black Film Festival

Starting in 2005, the festival sought to showcase Black cinema and bring light to the types of movies often ignored by the mainstream media. Nearly 20 years later, after having welcomed thousands of guests, received international media coverage, and shown films from over 50 countries, the Montreal International Black Film Festival (MIBFF) is still going strong. This festival’s activities aren’t restricted to any one week; they put on workshops, film screenings, debates, and round tables all year round. The MIBFF also maintains a serious commitment to discovering and fostering new talent while seeking to develop the independent film industry in Montreal and across Canada.

A Conversation with Charlene Carr

This virtual event hosts author Charlene Carr as she discusses her debut novel Hold My Girl. Feb. 8, 2:00-3:00 PM

Streaming online via Zoom Free

Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Sorcerer McGill Savoy’s main stage production returns to Moyse Hall after two years with The Sorcerer by W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan, Feb. 10-11 and 17-18.

Moyse Hall

Tickets: $15 for students, available for purchase here

Montréal : An Orchestral Rendition of Biggie vs 2PAC

Alternative Symphony’s East Coast Orchestra performs the Notorious B.I.G’s hits and the West Coast Orchestra performs the 2Pac classics!

Feb. 10, 8:00 PM

Tickets: Available online

BLACK ICE—Montreal Premiere with Guest Speakers!

Join Cinema Politica Concordia for the Montreal premiere of BLACK ICE, a film film about systemic discrimination in Canadian sports—in particular anti-Black racism in hockey, followed by a Q&A!

Feb. 13, 7:00 PM

NAACP Image Awards

Finally, coming in a little more prominent than the previous two, are the NAACP Image Awards. Founded in 1967 as a response to Hollywood’s exclusion of Black talent, the awards show was created by the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) in the United States. Today, the show boasts over 40 different categories, with awards across television, film, music, and literature. The event is broadcast live annually on Fox Network, with this year’s ceremony airing on Feb. 25.

While there is a lot to be desired with acknowledging Black talent in Hollywood, there is also reason for cheer. And who knows? If the focus shifts to institutions that are praising Black talent—and they are praised loudly and proudly—other awards institutions might have no option but to join in and celebrate it, too.

The 2023 Toronto Black Film Festival will run from Feb. 15-20. The 2022 Montreal International Black Film Festival ran from Sept. 20-25.