5 minute read

Data scraping reveals Montreal’s hidden property owners

Large companies hide property ownership while practicing predatory rental practices

Atticus O’Rourke Rusin Staff Writer

Advertisement

With the school year closing fast, one thing on returning students’ minds is finding a new apartment. However, many students will struggle throughout the process, facing high competition and prices, adding to the already stressful experience of moving into a new place.

In the 1990s, Montreal, and Canada as a whole, began leaning into policies that would simplify a process called financialization for real estate companies, including legalizing real estate investment trusts (REITs). Financialization is when financial companies, such as Metcap Living, buy residential properties with the hope of increasing the payout for company shareholders.

A variety of factors contributed to more instances of financialization in the housing rental market, like REITs—large financial institutions that specialize in buying up residential properties—higher demand for rental housing following the 2008 global financial crisis, and the deregulation of rent control and tenant protections.

Since businesses are not inclined to share financialization data with the public, University of Waterloo PhD student Cloé St-Hilaire and McGill PhD student Mikael Brunila decided to wade through the financial muck to find it. In a recent article supervised by David Wachsmuth, associate professor of urban planning at McGill, the two graduate students tracked the ownership data of a number of financial companies in Montreal, including the top 600, who altogether own around 32 percent of Montreal’s apartment units.

“One of the points we want to bring home most forcefully is that this is the type of information that should be available for everyone living in a city so that they can encounter landlords on equal footing,” Brunila said in an interview with The McGill Tribune

Brunila had the difficult task of figuring out how exactly he and St-Hilaire would collect the data they were looking for. Montreal maintains a public database detailing the owner of every building in the city. But individuals must look up each building one at a time to see who owns it. This time-consuming task prevents the average city-dweller from tracking all the buildings owned by any single entity of interest.

Brunila used a method called data scraping, where a computer program collects and copies large quantities of data from the internet, to find the names of the firms that own real estate in Montreal.

“After we had this data, it gives kind of a starting point,” Brunila said. “If you go and look up in the registry of companies in Quebec, […] you’ll find that that company is not owned by people, it’s owned by other companies.”

This led to another round of data scraping, this time to track the breadcrumbs left by each company leading to their parent companies. Once the researchers had both sets of data, they were able to draw several conclusions about financialization in Montreal.

The team arranged data into clusters, grouping similar data points into collections and analyzing them according to similarity. For this study, people were grouped together according to how they are affected by financialized apartments.

“When we did a clustering analysis, it gave five clusters total, but there were two clusters that were more prone to have financialized landlords in them,” St-Hilaire said in an interview with the Tribune . “The first cluster is called financialized precarious students.”

This means that students are particularly likely to find themselves living in financialized apartments, which explains the increased difficulty of finding affordable student housing: Financialized apartments are more prone to rent increases and predatory landlord practices such as harassment and eviction.

The second largest financialized cluster was renters willing to pay higher prices for newer units. New buildings are often funded by financial firms and funds as Montreal does not enforce rent controls for the first five years following the completion of a building’s construction.

Since companies are wary of this data getting out, they have already taken action against this research. After Brunila scraped the data from the website, a CAPTCHA was installed, which is a test to separate humans from computers, to prevent similar techniques from taking advantage of the same vulnerability that he found.

K. Coco Zhang

Contributor

Pulmonary infections— such as COVID-19 and the flu—in which bacteria or viruses enter and damage the lungs, are among the leading causes of death in older adults. Elderly people’s increased susceptibility to pulmonary infections is attributed mostly to immune systems that weaken over time.

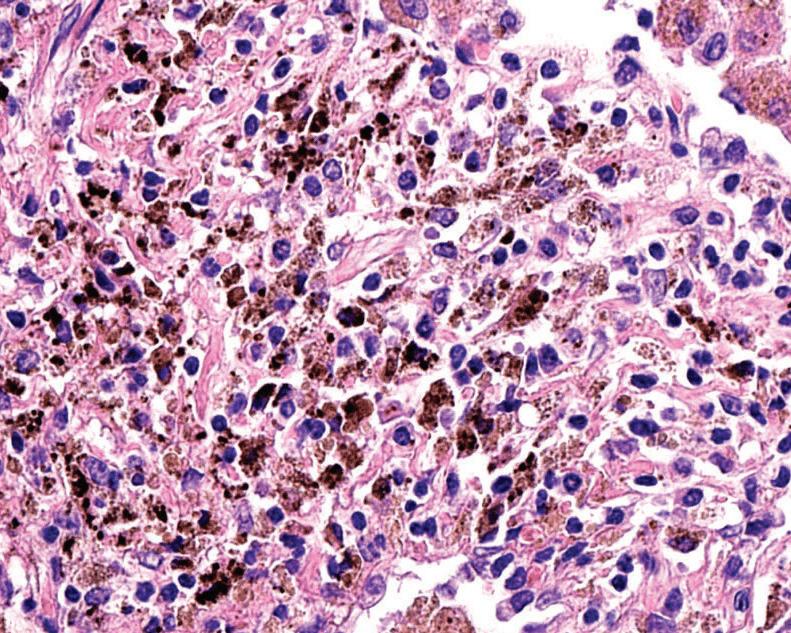

The initiation of immune responses to protect against lung damage involves a key group of players known as alveolar macrophages (AMs). Recently, McGill researchers discerned previously unknown mechanisms behind AM growth and longevity. Their recently published study provides important insights into the processes that affect the selfproliferation of AMs and the intricate connections between neonatal neutrophils—white blood cells found in newborns—and AMs.

AMs are a type of tissueresident macrophage, an immune cell that takes on diverse roles, including blood vessel formation, bone degradation, and activation of immune cells. Tissueresident macrophages are found in the tissues of various organs, such as the brain and intestines, and perform tissue-specific functions. Alveoli, the tiny air sacs in the lungs where gas exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide occurs, contain AMs.

“AMs are critical for pulmonary homeostasis and immunosurveillance, and they can both initiate the immune response and the resolution of inflammation,” Maziar Divangahi, a professor of medicine at McGill whose lab led the study, wrote in an email to The McGill Tribune . “For example, AMs are the first immune cells encountered in the airways by respiratory viruses, such as SARS-CoV-2, and contribute to viral clearance, limiting lung damage and promoting tissue healing.”

AMs also help remove excess surfactant, thereby maintaining lung homeostasis—the proper functioning of the lungs. Lung surfactants are materials produced by alveolar cells that prevent the collapse of alveolar walls when exhaling; they are essential to normal lung function. But, when an excessive amount of surfactant is produced by alveolar cells or when AMs fail to remove the surfactant, the gas exchange that takes place in alveolar walls can be significantly hindered, making breathing more difficult.

“AMs are crucial for many aspects of lung immunity, and they represent an excellent target for promoting healthy lungs,” Divangahi wrote. During embryonic development, AMs develop from fetal monocytes, which are white blood cells derived from the bone marrow and precursors to macrophages. Upon maturation, AMs self-renew throughout their lifespan, contributing to their remarkable longevity in the lungs.

In the new paper, Divangahi and his team found that the absence of 12-HETE, a derivative of fat molecules, led to a significant reduction in AMs in the lungs. This reduction was attributed to elevated levels of prostaglandin E2—a ubiquitous lipid mediator.

The paper also explored variations in immune cell func -

Alveolar macrophages represent around three to five per cent of all cells in the lungs of healthy individuals. (Elena Dantes / ResearchGate) tions in different stages of life.

“While adult neutrophils, [a type of white blood cell that fights infection], don’t express 12-HETE, our study shows that the neonatal neutrophils do,” Divangahi wrote. “This highlights the fact that the function of immune cells in neonates versus in adults is diverse, which is incompletely understood.”

In other words, excess prostaglandin E2 production acts as a brake on the proliferative self- renewal of AMs, impairing immune function. The impaired immune function characterized by reduced numbers of AMs could increase the risk of acute lung injuries and lung infections, such as influenza A virus and SARSCoV-2.

As researchers delve deeper into understanding AM mechanisms, Divangahi envisions these cells to be a revolutionary panacea in lung health and medical intervention.