8 minute read

McGill exoplanet specialist recognized for outstanding work in astrophysics

Professor Eve Lee named recipient of 2022 Vainu Bappu Gold Medal

Harrison Yamada Staff Writer

Advertisement

Last month, the Astronomical Society of India awarded McGill physics professor Eve Lee the 2022 Vainu Bappu Gold Medal for her work in astrophysics. The award honours young astronomers—typically under 35—for their exceptional achievements and potential.

Lee’s work focuses on exoplanets, which are planets that orbit around other stars in solar systems outside Milky Way. Studying the behaviours of exoplanets can provide information about the origin of our own solar system, including the conditions necessary for creating life—something Lee finds particularly fascinating.

“I am very much motivated by all the interesting and unexplained patterns and trends we see in the observed properties of exoplanets,” Lee said in an interview with The McGill Tribune

Many of the patterns and trends Lee studies manifest in the way planets form, grow, and organize themselves. Relationships between the masses of planets and their host stars, or the chemical composition of exoplanet atmospheres and cores, are just some of the topics that Lee researches.

One of the challenges of astrophysics, however, is building experiments since the systems being studied are too huge and too far away to manipulate in a lab.

The nearest star, excluding the sun, is Proxima Centauri b and it is over four light-years away, meaning that radio communication of a single message would take over four years. Comparatively, the farthest object ever sent into space, Voyager 1, has travelled less than one per cent of that distance.

To circumvent this issue and not stall research, Lee and other astronomers depend on telescope observations to gather information. Techniques such as spectroscopy—matching colours of light signals observed by telescopes to the elements known to emit those signals—can be used to gain insights about the material composition of exoplanets that cannot be directly measured.

Another common technique, called the radial-velocity method, uses the change in light signals from moving exoplanets to determine how quickly planets are moving. This change is quantified by the Doppler Effect, a measurable difference in the light emitted by an object moving away, as compared to an object moving closer. By comparing the light emitted by exoplanets at different parts of their orbit, astronomers can figure out details such as the planet’s orbital velocities and distance from host stars.

Using data like these, Lee tries to piece together more complex inferences about how exoplanets are formed, what they’re made of, and how they behave.

Lee has conducted her research at institutions across Canada and the United States, including the University of California, Berkeley, the University of Toronto, and McGill, ever since she completed her undergraduate studies in 2011.

According to Lee, she learned many of her most important research skills as an undergraduate.

“In research, it is important to come up with multiple ways to verify one’s result, and so coming up with various sanity checks is something I tried to build on since my undergraduate years and it is also what I emphasize to the students in my group,” Lee said. “In addition, I would say patience and tenacity in carrying out research is also an important quality that can be built from undergraduate years.”

As for navigating the world of academia and the challenges that she faces as a woman in the male-dominated field of astrophysics, Lee credited support from mentors over the years.

“I was very fortunate to have had numerous mentors throughout my academic career, with whom I still keep in touch. I think having this network of mentorship helped me navigate various challenges I came across,” Lee said.

Lee feels honoured to receive the Vainu Bappu award.

“Receiving this award is a good opportunity to have students and junior scientists be excited about the research being done in my group and also more broadly to motivate them to pursue what they are interested in.”

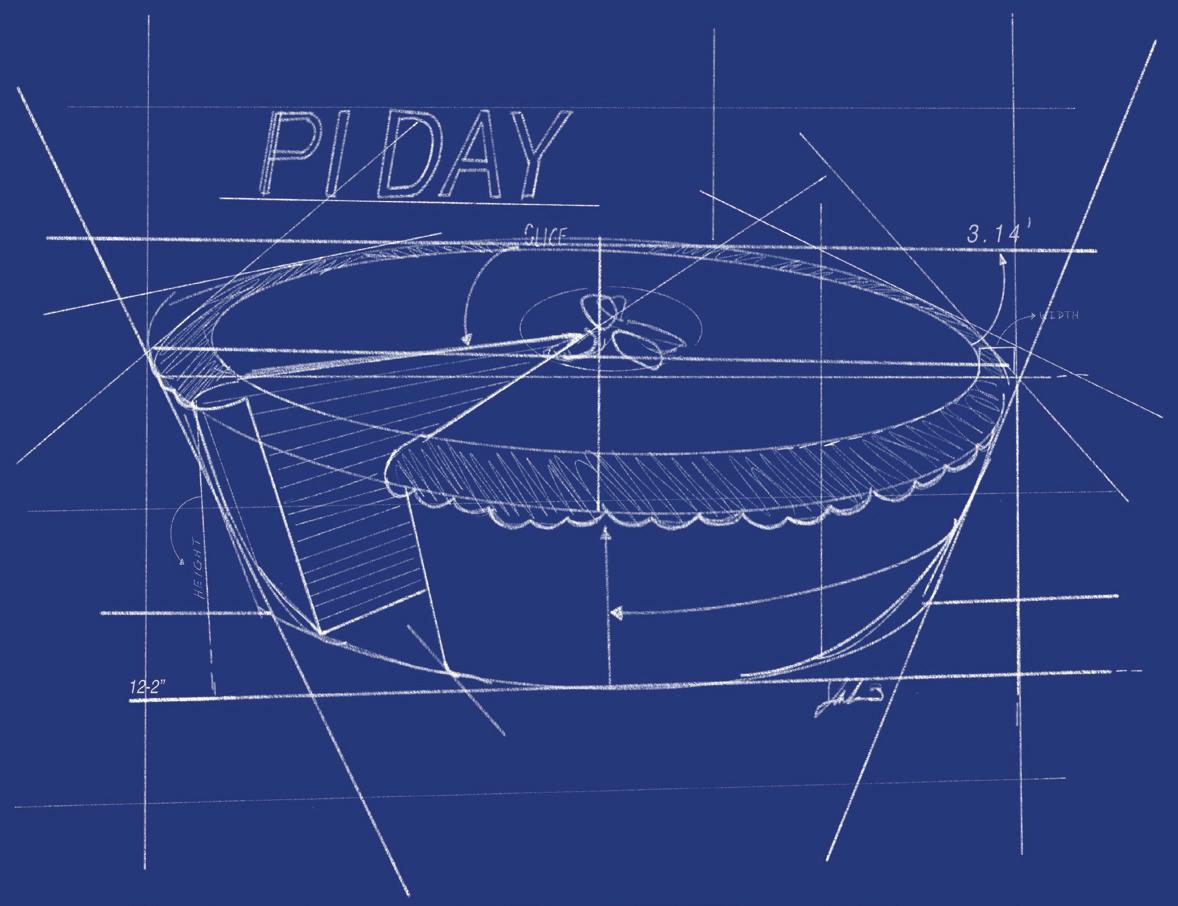

SciTech Presents: A Pi Day Pie Recipe

A simple apple pie recipe to help you celebrate math’s biggest day of the year

Ella Paulin Science & Technology Editor

Happy Pi Day! In a break from our regularly-scheduled McGill research coverage, The McGill Tribune’s Science & Technology section brings you one of our favourite apple pie recipes to celebrate an iconic day. Pi is a mathematical constant that represents the ratio of a circle’s diameter to its circumference. Crust us when we say that as science enthusiasts, we have the most awe-ins-pie-ring recipe to fill your day.

Ingredients

For the crust:

• π cups of flour

• π tsp of sugar

• 1 tsp salt

• 1 ¼ cups shortening

• ¼ cup butter

• 1 egg

• 1 tbsp vinegar

• 4-6 tbsp cold water

For the filling:

• 6-7 Granny Smith apples

• 1 tbsp lemon juice

• ½ cup sugar

• 2 tbsp flour

• 2 tsp cinnamon

Start by making the crust:

• Mix the dry ingredients (flour, sugar, and salt) together.

• Combine the butter and shortening with the dry ingredients. Cut the fat into 1-inch chunks and then use a fork or two knives to cut it into the flour mix. You can also use a food processor if you have one on hand. Either way, you’re looking for a crumbly texture, which has small chunks of fat that are not larger than a pea.

• Once you have the butter all mixed in, add the egg, vinegar, and 4 tbsp of cold water. If the dough is a little too dry, add water bit by bit until you can easily shape it into a sphere—make Archimedes proud.

• Shape the dough into two discs, cover each with cling wrap, and refrigerate for half an hour.

While the crust is chilling, preheat the oven to 400°F, and prepare the apples:

• Peel the apples and cut them into practically two-dimensional semi-circles.

• Put your apples into a bowl and mix in the lemon juice, sugar, flour, and cinnamon, as well as some ginger, nutmeg, or allspice if you want.

• Toss until the apples are coated and set aside.

Once the half-hour is up, you can begin assembling.

• Take one of the discs of dough out of the fridge. Put some parchment paper down underneath the dough and another layer on top to stop it from sticking to the rolling pin. It won’t hurt to put some flour on the parchment paper as well. Roll the dough out until it is several inches wider than your pie tin.

• Lift the parchment paper off the table, taking the top layer of paper off, and rotate it 180 degrees into the pie tin, trying to centre the crust in the pan. You should then be able to peel the remaining parchment paper off the crust fairly easily.

• Once the crust is on the pie tin, gently press it into the inner corners.

• Repeat the rolling process with the second disc of dough. Do this before you add the apples so the bottom crust doesn’t get soggy if you take a while to roll out the top.

• Pour the apple mixture into the pie plate, taking care not to pour in any liquid that has collected in it.

• Place the second crust on top and cut off any excess, leaving a fringe of about one centimetre. Crimp the crust however you like. One popular option is to press the tines of a fork into the crust around the circumference of the pie tin. You can also press the fringe of the crust between your thumb and your first two fingers in order to create a small V-shape, and then continue this pattern around the edge, trying your best to emulate your high school calculus teacher’s sine wave graphs. Either way, the important thing is to press the bottom and top crust together to create a seal.

• Make a couple of slits in the top crust of the pie with a sharp knife so hot air can escape while baking.

• Bake at 400°F for 40-50 minutes, until the crust is golden brown and the filling is bubbling. If it looks like the crust may burn, turn the heat down to 350°F or cover the edge of the crust with some tin-foil.

• Allow the pie to cool for half an hour and enjoy!

Growing up, I dreaded going to India every summer. The prospect of leaving France to spend two months in the heavy heat, shuttling from one family member to another, and having to speak Tamil brought me nothing but anguish and desperation for cancelled flights. My resentment of my Indian identity extended to every aspect of my life. I would doggedly refuse to address my mom in Tamil, cry for hours to avoid wearing a churidar, and sulk on our way to the temple. Apart from my mom’s cooking, I rejected every link to my Indianness—I just wanted to be a French kid.

Despite my obstinance, one memory from my annual stays remained with me: The Chennai train station. Ironically, I first encountered it in France, on the screen. Among the few Indian movies my parents and I ever watched was Madrasapattinam a historical romantic drama set in Chennai—then called Madras—at the time of Independence.

I was about six years old when I first saw Chennai with my own eyes. Years later, my memories of that first visit are still visceral, as if it was just yesterday when our cab drove out of the Chennai Central Station and into the chaos of the city. Al though modern-day Chennai is far different from the 1940s colonial setting of the movie, the station and its clock tower, where the two lov ers fought for their impossible love, stood still in time. Everything was just like I imagined it to be. For the first time in my life, I recognized a piece of myself in India. The memory of Madrasapattinam gradually faded as I grew up. What was once my favourite movie and the core of my nascent Indian iden tity became more and more difficult to grasp. Summers in India went by, each one more alienating than the last as a growing language bar rier—an invisible wall—stood between my family and me. Every word I pronounced was tainted with a sharp French ac cent I couldn’t even notice un til I was asked to repeat myself. Slowly, this fear of making a fool of myself, of being unable to prove myself worthy and legitimate of my Tamil heri tage, led me to lose it. While my younger self—the one who would dream of roaming the streets of 1947 Chennai— spoke a charmingly flawed but intelligible Tamil, what was once my mother tongue faded to be nothing more than just my mother’s tongue.

Yet, I remind myself that language preservation is a product of transmission, not a signifier of cultural identity. Growing up with a multicultural upbringing, my Tamil dad and my elder sister both spoke to me exclusively in French, while my mom used a mix of both languages, a sweet in-between that now sounds just like home to me. My own experience is far from unique, and is merely just the reflection of a larger trend among second-generation immigrants across the world. In 2006, a study by Statistics Canada found that only 55 per cent of Canadian children born to immigrants could communicate in their parents’ native language.

This loss of heritage often goes hand-in-hand with a sense of guilt and resentment. As I look at my mom for help with panicked eyes while her father—my only remain for immigrant communities. Under the guise of Equality, France refuses to see our colours, washing over our individual distinctions. France neglects our identity with such tenacity that it is even illegal to collect statistics indicating directly or indirectly the racial or ethnic origins of persons. By forcing its universalist ideals on communities, France drives cultural loss for second-generation immigrants. Nonwhite French citizens like me tend to push their ethnic background aside and stress their Frenchness to assert their right to exist in every space and belong in society. In the eyes of many, often white, French citizens, opposing the daily that I won the lottery—and my experiences are merely anecdotes compared to the financial struggles