5 minute read

By the Numbers: Reporting at McGill Breaking down annual reports on harassment, discrimination and sexual violence

Juliet Morrison News Editor

The annual reports of the Policy on Harassment and Discrimination and the Policy Against Sexual Violence were presented to the McGill Senate on March 22. Both policies are handled by the Office of Mediation and Reporting (OMR), which oversees inquiries and reports made under the policies. The McGill Tribune breaks down the annual reports and examines the 2022 numbers.

Advertisement

Policy on Harassment and Discrimination

McGill’s Policy on Harassment and Discrimination outlines how one can seek redress after an incident of harassment or discrimination.

Per the Policy, harassment is defined as “any vexatious behaviour [...] in the form of repeated hostile or unwanted conduct, verbal comments, actions or gestures, that affect the dignity or psychological or physical integrity of a Member of the University Community.”

Discrimination refers to illegal discrimination under Quebec law on the basis of “race, colour, sex, gender identity or expression, pregnancy, family status, sexual orientation, civil status, age (except as provided by law), religion, political conviction, language, ethnic or national origin, social condition, a disability or the use of any means to palliate a disability, which results in the exclusion or preference of an individual or group within the University community.” Under the Policy, it can include “both the actions of individual members of the University and systemic institutional practices and policies of the University.”

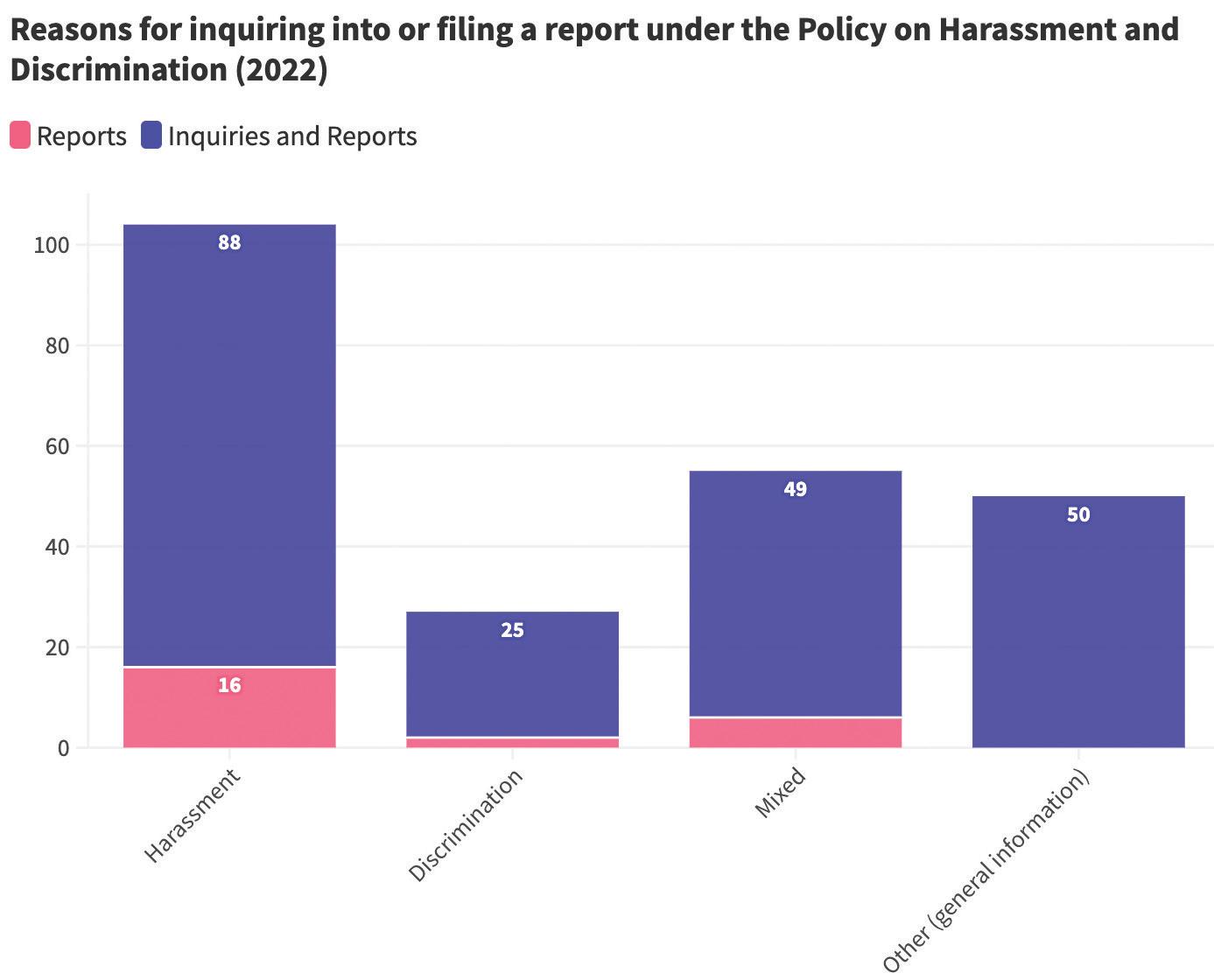

The reporting process starts at the OMR, where any member of the McGill community can inquire about filing a report or accessing support services. Between Jan. 1 and Dec. 31, 2022, the Office received 212 inquiries about reporting under the Policy.

Associate Provost (Equity & Academic Policies) Angela Campbell, whose office is in charge of preparing the annual reports, told the Tribune that the numbers show an uptick in the Policy’s usage. She attributed the upward trend to increased awareness about available reporting channels.

“The trends show [...] that there’s an increase in the uses of the policies for sure. And an increase in accessing the services at the university, especially around seeking information,” Campbell said. “So if you look at the number of people who [request] information, that’s certainly gone up over time.”

The majority of inquiries, however, do not lead to formal reports. Out of 212 inquiries in 2022, only 24 reports were filed.

Ultimately, 12 reports were eliminated because they either went beyond the Policy’s scope—meaning they did not occur in the McGill context with both parties as members of the McGill community at the time of the report and the alleged incident—or the issue was resolved through a different internal conflict-resolution channel identified as more appropriate by the OMR.

Campbell noted that though 12 reports might seem small compared to the McGill population of 50, 000, the number is still consequential.

“Twelve reports is 12 people [...] who felt that the matter was serious enough, and were able to muster up the strength to be able to file a report and go through a full investigation,” Campbell said.

A person filing a report can choose between two processes: Mediation or investigation. Mediation is a process where a mediator facilitates discussion about the reported incident between the parties involved to reach a resolution that all parties believe is appropriate. An investigation is a formal process that can result in disciplinary action against the respondent if university assessors—typically OMR full-time staff—find that harassment or discrimination did occur.

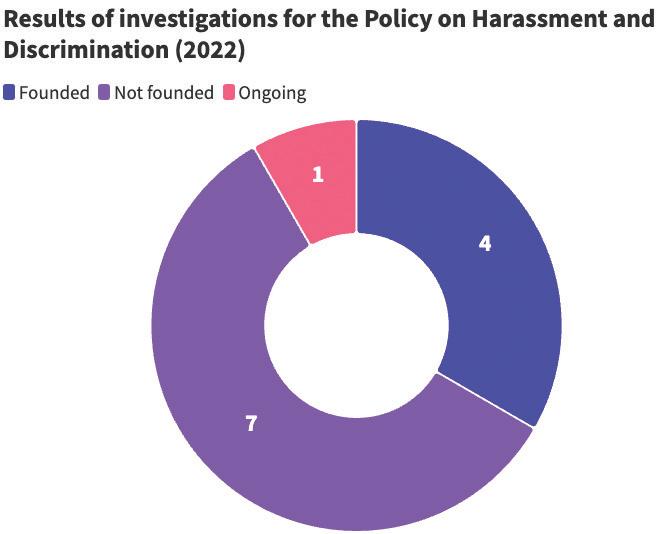

Of the reports filed in 2022 that fell under the scope of the policy, eight were about harassment, one about discrimination, and three fell into the “mixed” category. All of these reports proceeded to an investigation, meaning none of the reporters withdrew their report or reached an agreement through mediation.

If an investigation finds that harassment or discrimination as outlined in the Policy took place, the Provost will then refer the case to university disciplinary authorities for next steps. In 2022, all founded reports resulted in disciplinary action for the respondent.

Policy Against Sexual Violence

The Policy Against Sexual Violence covers McGill’s educational initiatives around sexual violence, procedures for reporting, and the activities of McGill’s central sexual violence support service, the Office for Sexual Violence Response, Support, and Education (OSVRSE).

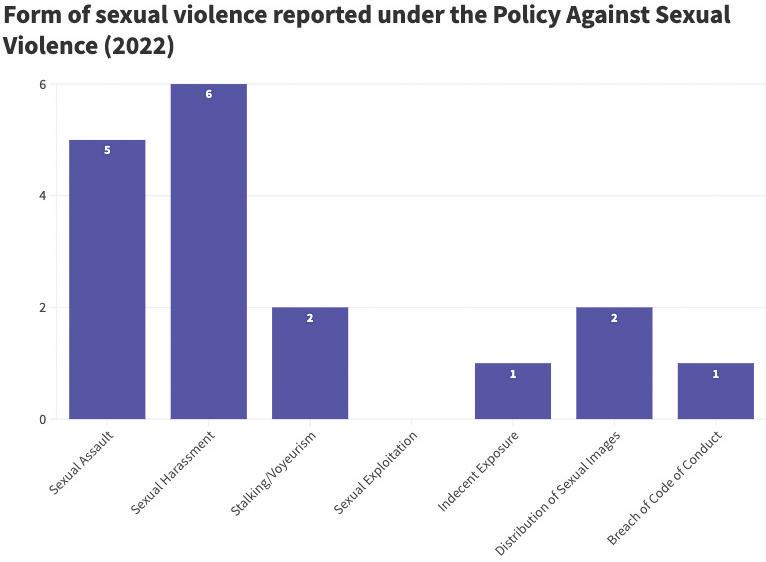

McGill recognizes seven categories of sexual violence: Sexual assault, sexual harassment, voyeurism/ stalking, sexual exploitation, indecent exposure, distribution of sexual images, and breach of the Code of Conduct (sec. 8).

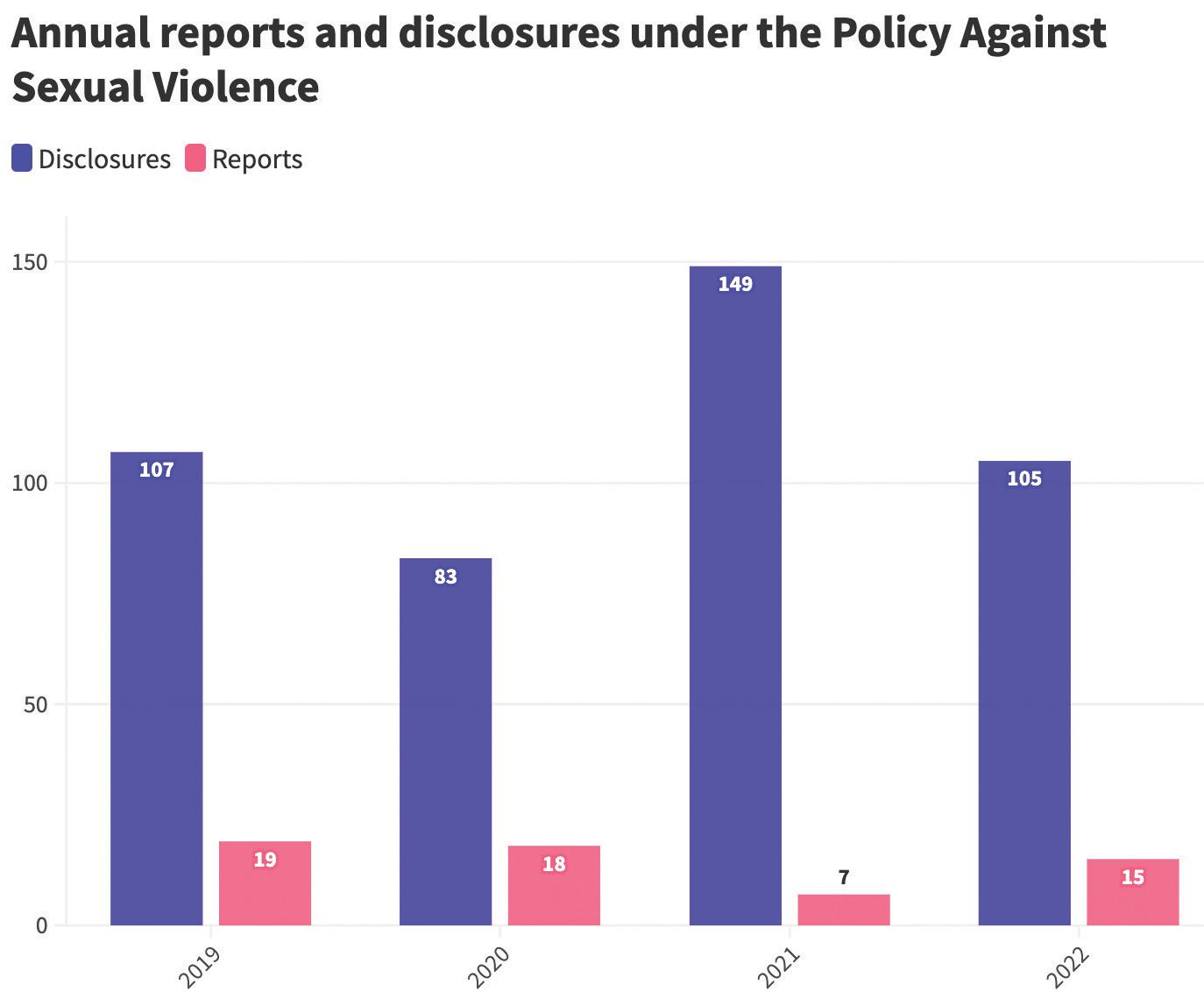

In 2022, there were 105 disclosures of sexual violence. Although the Policy outlines OSVRSE as the main body in charge of receiving disclosures, beginning in mid-October, the Office of the Dean of Students took over the responsibility as OSVRSE was closed.

Just like the Policy on Harassment and Discrimination, the majority of people who disclosed an incident of sexual violence decided not to file an official report. Only 15 out of 105 disclosures became reports in 2021-2022, three of which were out of the Policy’s scope.

**There was a slight overlap between the 2019 reporting period (April 2019 - March 2020) and the 2020 reporting period (Jan. 2020 - Dec. 2020)

After a report is filed, the OMR will review it and decide whether the university has jurisdiction to pursue an investigation.

If a report falls within the university’s jurisdiction, an independent special investigator (SI) will begin an investigation process to determine if an incident of sexual violence occurred.

Most reports were filed under the categories of sexual assault (5) and sexual harassment (6).

*One report under the Policy can contain more than one form of sexual violence.

Although SIs are given 90 days to complete their investigation, only three investigations were wrapped up within that period. The university can provide an extension in complex cases or “where the parties or a witness delay meetings with or responses to the investigators.”

Two of the delayed investigations concluded within a week of the 90-day deadline. The third required an additional 120 days because the survivor withdrew from the process.

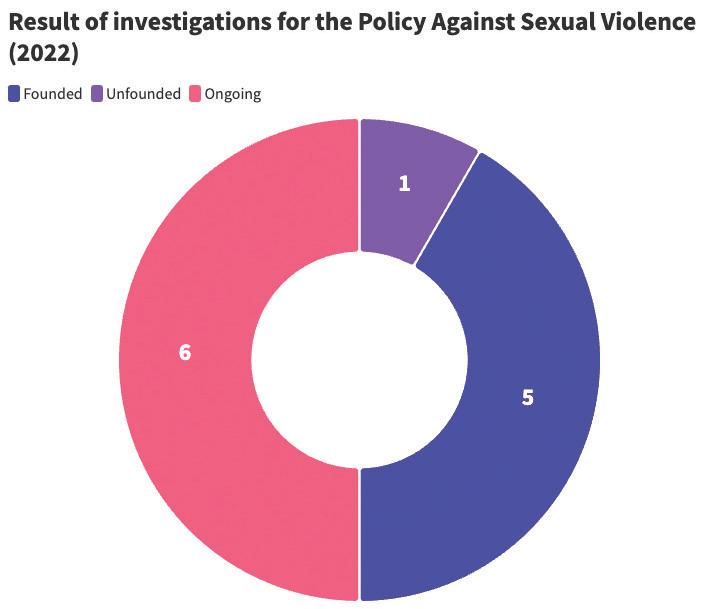

Of the 12 reports investigated this year, five were founded, one was unfounded, and six were ongoing by the end of the reporting period.

Disciplinary measures were imposed in all cases, except for one where the respondent left McGill. In the single unfounded case, authorities also imposed disciplinary measures as they found that the respondent’s actions during the alleged encounter constituted a breach of the Code of Student Conduct and Disciplinary Procedures.

In an interview with the Tribune, senior employment equity advisor Sarah Pierre said she was “encouraged” that an increasing number of community members were accessing the OMR.

“All of the awareness and campaigns have shown that the OMR is more top of mind for people and they know that there is somewhere they can go for formal reports,” Pierre said. “I think people are more aware of their rights as well as feeling more empowered to actually come to the OMR with their stories and with their questions and concerns.”

Although reporting and investigations are complex, Campbell expressed that she was confident in McGill’s procedures.

“For us, it’s really key to make sure that we have very, very strong, sound investigations,” Campbell said. “We really need strong experts to do the work of carrying things out so that the parties feel that they’re not being [...] victimized or retriggered in the process. And at the same time, the entire thing [must be] marked by procedural fairness, that’s really unimpeachable.”