21 minute read

Easy Hikes to Fire Towers

LIKE HER DAD, my daughter enjoys lists — the discipline of checking off a little box, the ecstatic comfort of seeing and visiting it all. I understand.

And so, when the adventure of visiting each active fire tower in New Hampshire presented itself, my choice of hiking partner seemed clear. The hikes to the fire towers are, for the most part, easy to moderate, accessible to the general public, offer excellent views for minor effort, and given my daughter’s adoration for bugs, seemed a perfect way to spend a summer.

I had already climbed to several of the towers, in a few cases with my other, older “daughter” Janelle, when she and I spent a year climbing a hiking list called the 52 With a View. That adventure resulted in my first book, “The Adventures of Buffalo and Tough Cookie,” and the possibility of a second list to climb and a second book with a second daughter felt exactly perfect.

While the new list was short, Uma’s age when we climbed them (4 to 5) made a big difference. When Janelle was climbing, she was 9 to 10, allowing her at times to become almost a hiking partner. A 4-year-old, it turns out, needed different incentive and guidance.

It didn’t take us long, though, to figure each other out, to become an adventure team, and I began to marvel to at how focused my daughter’s concentration could become if she was in the zone. On those days when we created a routine, took our time, made the hike about the journey instead of the summit, we were able to walk with clouds under our feet.

As it turned out, so many of the lessons I learned on that first round of hikes with a 10-year-old applied to a 5-year-old. Don’t rush. Learn the ground. Bring snacks. Let her tell me how she feels.

So, over the course of about a year, in the middle of an unprecedented global pandemic, my daughter and I took refuge amid the steel beams of fire towers, sheltering as high as we could, as often as was safe, with snacks and dirty fingernails and a desire only to see the world above the trees as purely as we were able.

In some cases, we drove. In others, we hiked. In all, we found a way to slow down, to appreciate history. And I marveled as my tiny hiker became stronger and more accomplished.

A strong, veteran hiker could tag all these summits in a long weekend. A family could take much longer. Each of these mountains, even if a mere hill, is as worthy a destination as their higher, White Mountain, cousins. For nearly a century, generations of people have been climbing these little mountains to look out over the same landscape, to bear witness to the rolling hills and find the smoke. To protect the land.

And now we’re part of that line of explorers, and soon you will be as well. The hot steel and long views are waiting for you. Bring a picnic blanket, strap on your binoculars, and see for yourself!

Author Dan Szczesny and his daughter Uma at Green Mountain fire tower in Effingham

WE BEGIN EASY

#1: Warner Hill, Derry We began with, by far, the easiest New Hampshire fire tower to reach, and one of the least visited. In the summer of 1930, using federal Emergency Relief Administration money, the state erected a new tower on the 605-foot hill, which at the time was a mostly treeless rise with unobstructed views all the way down to Boston and beyond.

Today, the tower site is neither treeless, nor tranquil. To the right of the short, crumbling paved road to the tower, a dog kennel provides us with a nonstop cacophony of yips and howls.

“Daddy, what is this place again?” Uma asks as we walk slowly up the road. I’ve left the car at the bottom, unsure how pitted the road is up ahead. The walk, though, is only perhaps a tenth of a mile.

She takes this in silently. This is new territory for her, a new approach to the

Uma takes in the view at the Red Hill fire tower in Moultonborough.

outdoors and to the forest — the beginnings of her understanding that even here, there is management, that we play a role in how the outdoors looks and how it relates to our connection to the trees.

The dogs howl, and the sun warms our backs, and before long we turn left off the road, and there it is. Uma tilts her head as far back as she can to take in the whole 40-foot tower. She pauses for the briefest of instants before breaking into a run.

Over her shoulder she yells, “We can climb up, right?!” So up we go.

She hits the bottom set of thin stairs at a run, and I struggle to keep up with her.

Indeed. We are also alone up here, surrounded by the warm metal and tops of trees. I lay out a picnic blanket, break out our strawberries and cookies, and we feast. We are barely 650 feet into the air, but we may as well be on the top of the world.

BLUE GHOST

#3: Mount Kearsarge South, Wilmot/Warner We are having a moment at the summit of Mount Kearsarge about 100 feet west of the fire tower. There’s been a tower atop Mount Kearsarge for years before the state parks on either side of the mountain had been established. The tower has had a phone line since 1933. For many years, there was a hotel on the summit.

But my daughter knows nothing of this and doesn’t even appear to be interested in the tower, shimmering in the blue-sky day. She steps slowly up to a nearby ledge, the summit wind threatening to lift her sunhat off her head, and looks out over the forest. She spins fully around.

I kneel down next to her and follow her finger.

“What do you see, baby?”

And I realize she’s not pointing at any one thing but rather at everything. She’s pointing at the view, this place of height and long sight, a rock visited by hundreds of thousands of people over the years. And now, a small girl, far above the treetops, experiencing, perhaps, her first real moment of awe.

I sit down on the warm rock next to her and my daughter pulls herself away from the views only long enough to sit in my lap. And there we stay for a while, surrounded by the great blue ghost, tower forgotten.

WE EARN OUR PATCH

#5: Pack Monadnock, Temple On this, our fifth journey to a fire tower, we are in Miller State Park, having driven up to the summit of 2,288-foot Pack Monadnock. The park today is jammed with hikers and tourists. Nearly every picnic table is crowded.

But we don’t care because today is special. Today, according to the rules laid out by the New Hampshire Division of Forests and Lands, after tagging five towers, Uma can collect a Fire Lookout Tower Quest Patch. We’ve invited several of our hiker friends to celebrate the occasion, including Ken Bennett, a local hiker and one of the nicest guys on the planet.

“Shall I get the arch ready?” he asks with a wink. Ken knows his way around hiker traditions. The earning of a patch upon the completion of a hiking list requires a very particular ceremony.

The hiking group lines the area in front of the steps leading up to the tower, and they all lift their hiking poles and sticks to form an arch.

“What are they doing, Daddy?” Uma asks.

I pull her close. “When a hiker is about to earn her patch, all her friends create a tunnel she has to walk through to celebrate such an amazing accomplishment.”

“It is,” I say, “you earned it.”

And so, on the 1,748 day of her life, Uma strides under that hiking pole arch like it had been a day she was training for all her life. And in some ways, it was. Our companions applaud and my daughter beams, the center of attention, the center of the universe.

GRASSHOPPER SYMPHONY

#8: Red Hill, Moultonborough There are not a few grasshoppers, or even many, at the hot, ledge-lined summit of Red Hill, there are legion.

Uma steps up onto the rocks under the fire tower, gently, like walking in slow motion, and spreads her arms wide — a tiny Moses. And the creatures respond. Dozens of them, hundreds, lift up into the air, miniature, bristling helicopters, their collective wings clack, clacking.

“Daddy,” she whispers, “Daddy, Daddy ...” unable to put her joy into words.

But I can. Watching her drift through this wave of clattering grasshoppers is an epiphany. I hold my breath, like I could fill my lungs with the air of this moment of grace and expel it into a sacred bottle later, magic air of a moment of connection between my daughter and the peculiar nature of a 5-yearold conducting a symphony of grasshoppers under the steel beams of a nearly half-century-old fire tower.

My daughter stands on a 2,000-foot platform in the middle of time. She waves her arms and her orchestra of grasshoppers — one of the oldest living herbivorous insects, dating back 250 million years to the early Triassic — rise up and sing, their tiny yellow, brown and brilliant green wings giving voice to the mountain.

And I wonder if this hike will be Uma’s power hike, the one that creates the future

Finding Smoke

A day in the life of a fire tower watchman

There is a routine and a rhythm to being a fire watcher, a finder of smoke.

This past May, an extremely dry air mass swept through New Hampshire, drying out the ground cover of leaves, needles and grass. The dry weather, compounded by relatively low humidity, led to a rash of late-spring forest fires, including several large ones in touristy areas of the White Mountains.

This has led to the state’s 15 active fire towers being staffed more than usual, and has kept fire watchmen on their toes.

First-year lookouts like state Forestry Aide Alton Hennessy are undergoing trial by fire on the job. Hennessy is one of the lookouts atop Mount Cardigan, one of the most popular of the tower destinations in the state, and he explains that being a lookout during a busy fire season requires a significant amount of skill, patience and an understanding of how the equipment, and fire, work.

Here’s what happens when a lookout sees smoke: First, they use a device called an Osborne Fire Finder to gain an azimuth (or measurement) of where the smoke is in relation to the tower. Then they use a topographical map to confirm that location. Other nearby towers are contacted to work together to triangulate the smoke to gain a more precise location. Finally, the tower will call the local fire dispatch center nearest to where the smoke is and the local fire fighters will head out.

“Once they’re on their way, I’ll continue to watch the smoke and help make sure they are heading in the right direction,” Hennessy says. “I can also help inform local responders as to what the smoke activity is and what color, volume and density.”

Hennessy is particularly knowledgeable about the characteristics of fire and smoke because he also works for the town of Canaan as an EMT and fire department captain.

“The skill sets definitely overlap,” he says.

Chief of the Forest Protection Bureau Steven Sherman points out that while the actual work of finding fires and directing crews is critical to the work of tower watchmen, the education element of being ALTO N up there in the towers meeting families and hikers plays an important role as well.

“Fire Lookouts serve as ambassadors for New Hampshire and our fire prevention programs,” he says. “They educate visitors about being safe with fire and about the importance of our forests and the need to protect them.”

To Hennessy, that’s one of the best aspects of the job, especially at a high-traffic mountain like Mount Cardigan.

“I get to meet people from all over the country and the world, and I get to hear their stories and they get to ask about what we do and how we do it,” he says. “And I get to promote the Fire Tower Quest Program as well.”

The state program offers hikers a certificate and patch if they visit five active towers around the state.

Besides the education element of the fire tower program, the state is gearing up to give the public a truly hands-on experience. Thanks to funding from the federal American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, the Division of Forest and Lands will be renovating several of the towers this year as well as four of the old watchman cabins near them.

“We plan to offer the watchman cabins for rental by the public so they can experience the adventure of staying at these remote locations,” Chief Sherman says.

That’s good news to both the public, and to tower watchman alike.

“It’s always nice to hear the surprised voices of visitors when they see the tower and say, ‘Oh, look, the tower’s open!’” says Hennessy.

HENNESSY woman, the moment that sharpens her resolve. The one where she begins to be something more than my daughter. The one where she begins to be Uma.

But now, she just turns to me, lowering her hands as the grasshoppers fall back to the stone and the concert subsides, and all that remains is her wide grin and the plaintive cry of a forgotten cicada.

IT ALL BEGINS WITH JOHN WEEKS

#10: Prospect Mountain, Lancaster Watching my daughter play in the considerable shadow of The Weeks Estate atop Prospect Mountain is a form of time travel. Without the stuffy Lancaster native and Massachusetts congressman, this book, the Northeast fire tower history and indeed the White Mountain National Forest would, at best, look very different today. Perhaps, in fact, those things might not exist at all.

“Who lives here, Daddy?” Uma asks. She’s skipping over a wide area of the grounds that used to be a tennis court for the vast estate. My wife and I hold hands as we stroll through the trails and property, there in the North Country, on a mild bluebird-sky day.

“How?” She’s only half interested, focused instead on the acorns and orange leaves scattered along the trail.

“Well,” I say, “he helped get a law passed that ...” My wife is laughing. I’ve lost my daughter’s interest. Uma is staring up at an abandoned bird nest in a nearby poplar, maybe 10 feet off the ground. I must admit that the bird’s nest is deeply more attractive than any old bill some long-past politician could write.

Still, when the Weeks Act was signed into law by President Taft on March 1, 1911, the sweeping consequences of the legislation would immediately be felt, and continues to be felt more than a century later.

The Weeks Act provided both preservation and management of the many acres of land that eventually fell under its jurisdiction. Loggers and railroad tycoons could continue to use the resources within reason, while at the same time, nature lovers and tourists would have access to the beauty of the landscape. All this seems obvious today, but around 1900, any glimpse at photographs from the White Mountain area made

Mount Kearsarge South fire tower

it clear how badly stripped the mountains had become, and how polluted and choked with silt the streams and rivers were.

Over the years, nearly 40 national forests, including Green Mountain, Pisgah and Allegheny, have been created out of the act. And most importantly for the little girl now running toward the peculiar stone fire tower on the grounds, the act provided money and instruction for the cooperation between state and federal authorities to develop and maintain fire-control measures.

One of those measures? Well, fire towers, of course. In New Hampshire, eight of the currently active fire towers were established within 12 years of the act being passed.

For my daughter on this day, there’s not much of interest with the tower. There are no stairs to climb. No views to attain. We do have lunch though, and that provides one moment of connection to this place.

We three explorers take a seat on a lookout

The Mount Kearsarge North fire tower, currently used as an observation deck, provides a 360-degree view.

A time-lapse photo creates a night sky swirl of stars at Pitcher Mountain.

When the WOOFS Looked for Smoke

Women lookouts are still working to make their mark

On April 20, 1943, 32 people showed up at the Gale River CCC Camp in Littleton to begin a threeday fire tower guard and lookout training program for the upcoming season.

Over the next three days, they would study compass and map reading, fire-suppression methods, and radio and telephone communications.

But this class, which was split into four groups, was different. In this class, for the first time, Group D consisted of all women. They would come to be known as WOOFS (Women Observers of the Forest), and they would become the first five women in New Hampshire to step into a role thought of by many as the exclusive universe of the rugged backwoodsman. News reports of the time often grouped the five together, a “unique troupe taking on these strange tasks,” wrote the Littleton Courier. The New York Times even suggested that “danger abounds” for these women from bears and lightning, as though those dangers didn’t exist for men.

This was all very curious to the women fire tower rangers from the West, who had been spotting fires since 1913, when Hallie Morse Daggett became the first woman fire tower lookout and began working at Eddy’s Gulch Lookout Station atop Klamath Peak in California.

Still, New Hampshire’s first women lookouts took it all in stride. When asked about her role as a tower lookout, Maude Bickford of Tilton skipped any drama and simply told a reporter, “I like the work.”

Though one would think the natural progression of women in towers would ramp up after that first class of five, that wasn’t the case. Through about 2012, only about 30 women had served as wardens or watchmen in the towers. For example, between 1911 and 1962 when it was torn down, only one woman, Barbara Mortensen, served as a warden atop Pine Mountain. Mortensen was one of the original class of five.

In recent years, however, the ratio of women fire wardens appears to be leveling out. One woman warden who helped pave the way for today’s female watchers is Kayrn Lothrop. For about 14 years, between 1998 and 2012, Lothrop worked atop Pitcher Mountain in Stoddard. She was working at the tower on 9-11. Today, she’s a state firefighter in Massachusetts.

“All I remember telling my councilor in high school was that I didn’t want a job where I had to sit behind a desk,” Lothrop says. “My dad was involved with the forest fire association and he always believed I could do anything, so that’s where it started.”

She grew up in Nelson and became a firefighter there before applying for a job as a state forestry aide. “There I was, in a warehouse next to the Concord bus line, with five rangers and the chief sitting at a huge desk and a map on the wall looking where they were going to put us,” she says. “I grew up on Pitcher Mountain, but they could have put us anywhere.”

But by the end of that hiring session, she had been selected to serve her hometown mountain.

Meanwhile, 90 miles away on the northern end of Lake Winnipesaukee, Fire Tower Watchman Kelley Brown has been looking for smoke from Red Hill Fire Tower since 2020. Her position is unique, since her tower is owned and managed by Moultonborough instead of the State. She doesn’t have the official status other wardens have, but she does the same work. Plus, since the town emphasizes public awareness of the role of fire tower, Brown gets to have some fun that other watchers can’t.

She had T-shirts and stickers made. And during the holidays, she comes up to decorate her tower with lights. And on some days, you’ll find Brown’s pup, Willa, hanging out at the tower with her.

“I’m the person that absolutely loves being on the hill,” she says. “It fills my soul in a way that other things can’t.”

K AY RN LOTHROP

KEL L EY BROWN

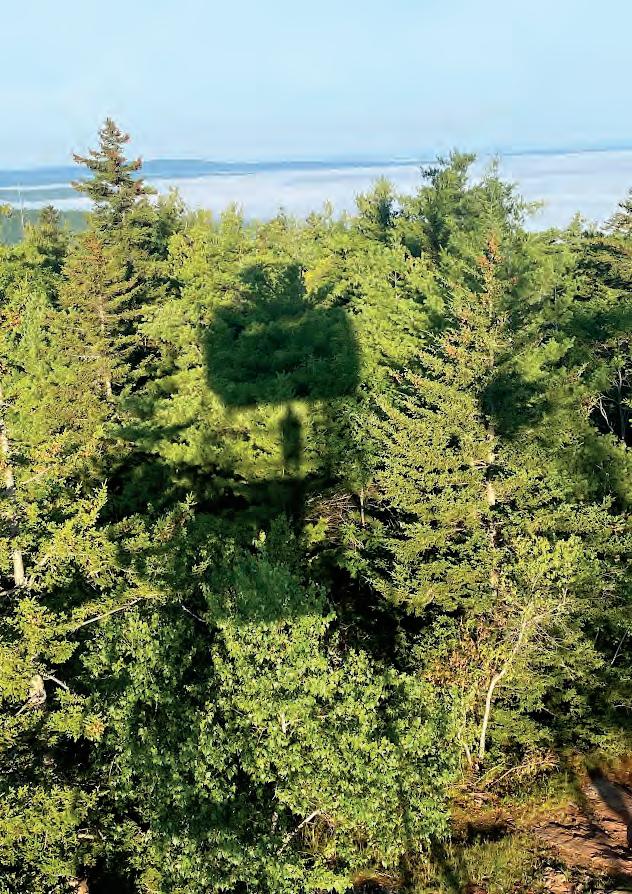

The shadow of the fire tower on Blue Job Mountain (an easy, family-friendly hike) in Farmington

bench, pull our hoods tight against the wind, and unpack peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and chocolate. We watch the clouds roll over the distant hills and talk about spiders and bird nests and towers touching the sky.

“You could see a fire from here pretty good, Daddy,” Uma says.

And I think, from here, next to my daughter and wife, I can see it all.

WIND AT OUR BACKS

#15: Cardigan, Orange I watch my 5-year-old stomp up the trail toward Mount Cardigan, the final climb on our active-fire-tower list, and I marvel at my life’s trajectory.

We cross little streams on bridges, kick our way through the piles of orange and yellow fallen leaves, and twist and turn along the winding trail until the ledges start becoming more prominent and the trees turn to scrub and bush.

“Daddy, what’s that?” She crooks her head upward toward the summit and we can hear it — the wind. Being above the trees inside a fire-tower platform in the wind is something different from what we’re about to experience. Even atop Kearsarge, as bare a summit as that mountain has, the weather was mild, the wind nonexistent. Not here. I know that sound.

Cardigan’s bare, expansive summit — the result of a series of forest fires from the 1850s — offers hikers unlimited, wide-open views. But in bad weather, this mountain can be as treacherous as any one of her 4,000-foot sisters.

I pull her off the trail into a scrubby area where we can prepare. We gear up with a heavy winter coat and gloves, and a pink bunny rabbit baclava for her. I pull out my own down and heavy gloves. And for a few minutes, we sit in the crook of a scrubby pine tree to have some snacks and get ready for what’s ahead. I sit with my back to the trail and she climbs into my lap, and there we are, a little team powering up on cookies and jerky and strawberries.

Finally, before we are about to head up, and as I did all those years ago with Janelle, I kneel down before my daughter to be eye level and say, “I want you to know how proud I am of you and of how hard you worked to get here. Pay attention to this and remember what you’ve accomplished today, OK?”

She smiles and nods and I pull her tight into a hug. “Are you ready?” I whisper into her ear.

“Let’s go!” she yells, and we’re off.

EPILOGUE

A week after we completed our initial quest, we turned our attention to the New Hampshire Past and Present Fire Tower List, a collection of 100 destinations that have active towers, old towers converted to observation lookouts or summits that used to have a tower on them. This is a tough list, featuring several long, difficult hikes to 4,000-footers like Cannon Mountain, Mount Cabot or Mount Bond. But the list also featured some beautiful, small, off-the-beaten-path and town hikes.

As I write this, we have 24 tower summits under our belts, nearly a quarter of the way there. And through it all, my daughter has led with ferocity, her head always turned upward, eyes searching for a tower there above the trees.

We walk on, my little adventurer and I, each of us keeping the other young, each of us following our paths together. There will come a day — perhaps as you read this, that day will already have happened — when my wife and both daughters will form a team. Perhaps just my two daughters will retrace my steps.

Until then, the steel and stairs continue to call to my tiny stomper. And I will follow her to all the fire towers at the ends of the earth. NH

Author Dan Szczesny’s new book, “Where There’s Smoke: On the Trail to New Hampshire’s Fire Towers,” arrives in 2023. Learn more at danszczesny.com.