6 minute read

Lost and Found: Finding New Hampshire’s lost or hidden places

By Marshall Hudson

New Hampshire is an old state rich with history and full of lost or forgotten places, some of which may be hiding in plain sight. If you are willing to get off the tourist trails and do some exploring, you can rediscover these hidden links to our past. To find the best of these lost places, you’ll need to be prepared to drive the backroads, talk to the locals, read old maps and maybe do some brush-busting. To get you started, here are a few lost places to find once the stay-at-home order is lifted.

Lost Fire Towers

The fire tower on Magalloway Mountain in Pittsburg

From about 1900 until the late 1960s, almost 100 of New Hampshire’s mountains sported a fire tower on their summit, and a warden watched out over the forest, sounding an alarm whenever he saw smoke. Many of these fire wardens, or “lookouts,” lived in a small cabin on top of the mountain near the tower. Today only about 16 towers are still manned, and much of the fire-spotting is done by airplanes. The old fire towers and cabins were prone to lightning strikes, high winds, fire, vandalism or just age and deterioration once they stopped being used. Most are gone now, lost forever to history, but in some places you can still find tower anchor pins, concrete footings or some remnant of the cabin. On the Starr King Trail in Jefferson, the cabin is long gone, but the fireplace remains standing, reminding us of New Hampshire’s fire tower heritage.

The Kiss’n Bridges

The historic Ashuelot Bridge in Winchester

By my count, New Hampshire has 54 covered bridges left over from the horse-and-buggy days when bridges were regularly built with roofs and sides to keep the elements from rotting out the wooden decking. With the development of iron, steel and concrete, the covered wooden bridge became obsolete. Remaining covered bridges have become lost or f orgotten as new roads diverted to steel and concrete bridges, which could carry heavier loads and faster traffic. Which of the remaining covered bridges is the best one to go find is a subjective opinion, but I’d suggest the Bath Village Bridge in Bath and the Ashuelot Bridge in Winchester. Both are not to be skipped.

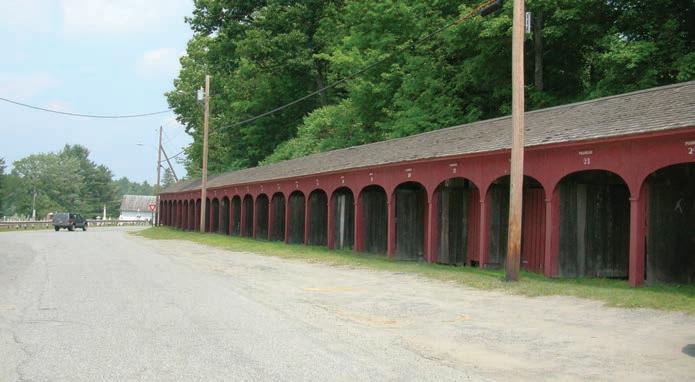

Lyme Horse Sheds

What remains of the sheds in Lyme is said to be the longest string of contiguous horse stalls in New England.

Gone and forgotten are the days before automobiles, when everyone traveled by horse. While you can park your car, lock and leave it, that didn’t work well for horses, particularly in bad weather. What do you do with your horse and buggy when you need to go to Sunday morning church service? At the Lyme Congregational Church, they solved the problem by building horse sheds.

A continuous line of individual horse stalls was erected on adjacent town land, and then the stalls were sold to church-go ing individuals (without the land). Above each stall they placed a numbered plaque with the owner’s name on it. Not only were the sheds available for use on Sun days, but also whenever the owner came in to town on business. At one time, there were two additional lines of sheds for a total of about 50 stalls, but once they were no longer needed most were removed, and only 27 remain today. This row of 27 sheds is said to be the longest string of contiguous horse stalls in New England. The sheds still sit on town-owned property, but are maintained by the Lyme Congregational Church with private funds. Saddle y our horse and go find these reminders of New Hampshire’s pre-automobile past.

Lisbon Charcoal Kiln

The stone kiln in Lisbon, which was once used to make charcoal for nearby iron smelters, is reminder of bygone days when charcoal was a commodity needed by blacksmiths and iron foundries. Pine knots and other waste wood material from nearby sawmills were slowly burned in a low-oxygen rock kiln to remove water and produce charcoal. Charcoal was the preferred furnace fuel because it burned more slowly than firewood and created a more intense heat that was better suited for the refining of ores. Charcoal also had the advantage of being locally produced as opposed to coal, which needed to be shipped into the state.

Madame Sherri’s Castle

The ruins of Madame Sherri’s castle on Rattlesnake Mountain in West Chesterfield

Finding the ruins of Madame Sherri’s castle on Rattlesnake Mountain in West Chesterfield isn’t difficult, but it is off the beaten path, and will likely only be found by those actively seeking it. The castle was once the home of Paris-born Madame Sherri, who lived extravagantly in this rural town. Madame Sherri was a Paris nightclub dancer and then a theatrical costume designer in New York City during the roaring ’20s. In the 1930s she bought hundreds of acres in Chesterfield and built a castle where she entertained New York friends with lavish parties.

Madame Sherri was said to dress scandalously, which caused some consternation among the local workers constructing her home. Reportedly, she often wore nothing at all except a black fur coat that she slipped into and out of easily. She was also seen wearing feathered boas and high plumed hats while traveling the muddy backroads in a chauffeur-driven Packard touring car. She bragged that she lit only one match a day, and used each dying cigarette to light the next one in a long-tipped cigarette holder always in her hand. Rumors persisted that she was involved with bootlegging during Prohibition, or that she was on the dodge from French authorities and using an alias.

Wherever her money came from, it dried up near the end of WWII and she moved to Vermont. She died in 1965 at age 87 as a ward of the town of Brattleboro. Brattleboro filed suit against “The Belle of Chesterfield,” seeking reimbursement from her estate for expenses and outstanding bills. In 1962, Madame Sherri’s castle was destroyed by fire, but the stone staircase remains for the curious to find.

METALLAK’S GRAVESITE

Many place pebbles, coins and other small tokens on Metallak’s grave in Stewartstown.

The Last of the Coashaukes is buried in a small cemetery on a dirt road in Stewartstown. Metallak, “The Lone Indian of the Magalloway,” was the last survivor of the band of Coashauke who inhabited the upper Androscoggin and Magalloway river watersheds. Metallak was known as the “lonesome chief ” because the majority of his people had died from smallpox, in the French and Indian War or had simply left their homeland. Metallak, however, was determined to stay in his ancestral lands and lived in a camp at Umbagog Lake. Legend says he was a skilled hunter who lived off the land, and that he once rode on the back of a moose until he was able to kill it with his knife. Metallak was friendly to the white settlers and guided them hunting, fishing and trapping.

Metallak went blind in one eye when he poked himself with a needle while sewing moccasins, and years later he lost sight in the other eye when he slipped and fell and a stick stuck him in the eye. He was found by trappers who brought him to Canada to heal. Wishing to return to his own camp, he hired a man to guide him back home, but the guide took his money and left him in Stewartstown, where he resided for a few years until he passed away about 1850, reportedly at the age of 120. If you visit the grave of Metallak, custom says to place a pebble, coin or some other small token on his headstone to show respect for the last of Coashaukes, gone but not forgotten.