5 minute read

A Place to Pick Strawberries

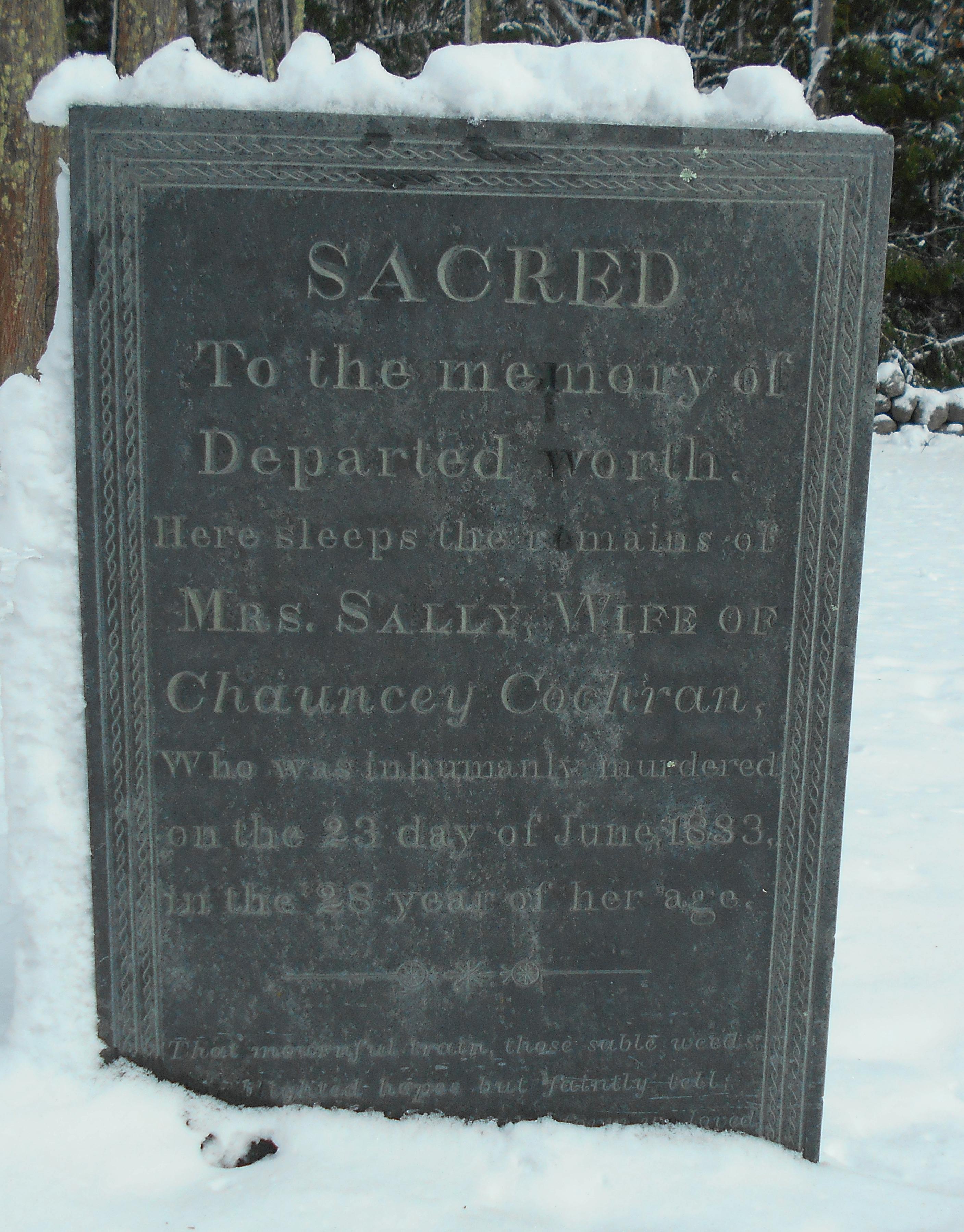

And the site of a bizarre murder

Story and photos by Marshall Hudson

I was working alone one snowy morning, following a brook in the northeasterly corner of Pembroke when an object that didn’t fit the surrounding environment suddenly caught my attention. Perhaps it was the grayness of the object contrasted against the stark white background of freshly fallen snow, or maybe the sharp-cornered squareness of the object situated within a stand of round hemlock trees that made it look out of place. Whatever the reason, it called out to me as I was passing by. Curious, I detoured from my route to investigate it.

The 2- to 3-foot-tall granite block was not something naturally occurring. It had been quarried, brought in and erected by a human. In these remote woods, someone had labored to put it here and must have had a good reason for doing so, as there would have been too much effort involved to have done it on a whim. Not being near any property lines, I ruled out boundary markers and town line corner stones. A grave headstone perhaps?

If it were a headstone, I would expect an inscription of names, dates or maybe a brief epitaph. I saw nothing obvious on any of the four sides. Exploring the rough and pitted granite surface with my fingers, I thought perhaps I felt a shallow engraving. Using a soft lumber crayon, I explored the grooves that perhaps I had felt. “1833” emerged. Nothing more. Probably not a headstone, I reasoned. If someone had gone through the effort of carving a year, either birth or death, into this stone, they likely would have also carved the name of the deceased. Hmmm ... perhaps “1833” wasn’t a year? Maybe it was a numerical marker for something, and there was a number 1834 nearby? Didn’t seem likely. So what had I stumbled onto?

Turns out that what I had found was a place to pick strawberries and the site of a bizarre murder that took place in 1833, the year carved on the granite. This unusual story is well told in the book, “I Have Struck Mrs. Cochran With a Stake” by Leslie Lambert Rounds. Rounds describes the true story of Mrs. Sally Cochran, who was murdered at this very spot while picking strawberries. The murderer, Abraham Prescott, was asleep and sleepwalking at the time he committed the murder. At least, that is what his defense attorney claimed at trial.

The murder took place on a Sunday afternoon, June 23, 1833, when 28-year-old Sally Cochran decided to go strawberry picking. Her husband, Chauncey Cochran, stayed behind with the couple’s children and his mother who also lived with them. Eighteen-year-old hired farmhand Abraham

Writer Marshall Hudson uses a lumber crayon to trace the year 1833 on the stone.

Prescott offered to accompany Mrs. Cochran. The two would head down into a low meadow owned by Chauncey’s brother and neighbor. The meadow was downhill some 300 feet away from the Cochran farm, and in full view of three or four of the neighboring houses.

The two started down the steep hill behind the farmhouse, but then deviated to a different pasture. Prescott suggested that he and Chauncey had been working in a different meadow a few days earlier and the berries over there were larger and easier to find. If Sally was concerned about heading into a remote area with an 18-year-old man, 10 years younger than she was, she gave no indication, and her husband raised no objection. Abraham Prescott had lived with and worked for the Cochrans since he was 15 and they trusted him, believing they knew him.

Sally was attractive and perhaps Prescott made a romantic advance that she rebuffed. It was suggested at the trial that he killed her in a rage of anger after being rejected. Another possible motive was that Prescott killed her and also planned to kill Chauncey, thinking he would end up owning the farm. Others might have considered the possibility that Sally and Prescott were having a romantic affair and it had gone sour, or that Sally wanted to end it. From his testimony at the trial, we learn that Chauncey Cochran trusted his wife and did not believe there was an extramarital affair taking place.

Abraham Prescott’s version of events was that while picking strawberries he’d suffered the onset of a painful toothache. Unable to pick strawberries because of the pain, he sat down and fell asleep. When he awoke, he realized that he had killed Sally Cochran — while he slept. Whether asleep or awake, there was no disputing that Prescott had picked up a fence post and struck Mrs. Cochran over the head forcefully enough to kill her.

As bizarre and unlikely as Prescott’s version of events might seem, this was not the first incident of Prescott sleepwalking and trying to kill the Cochran family. Six months earlier, Prescott had arisen in the middle of the night and struck both Sally and Chauncy with an ax while they slept. Both Cochrans survived the attack and recovered from their injuries. Prescott said that he was asleep at the time and had no reason for doing it, and no memory of it once awake. Oddly, the Cochrans did not press charges against Prescott or remove him from their household, apparently believing his sleepwalking attempted murder was a fluke.

The jury in Prescott’s murder trial was less forgiving than the Cochrans had been. While the Cochrans apparently believed the first attack was an extreme example of a loss of conscious control while asleep, the jury didn’t buy it as an excuse for the second attack that resulted in Sally’s death. Prescott was found guilty of murder and sentenced to hang. After appeals, a second trial, and a temporary stay of execution by New Hampshire governor William Badger, Abraham Prescott was hanged on January 6, 1836.

Sally Cochran was buried in a small cemetery near her farm home. Perhaps racked by guilt, grief, or haunted by painful memories, Chauncey Cochran sold the Pembroke farm, gathered up his children and moved to Maine. Abraham Prescott was discretely buried in an unmarked grave at an undisclosed location.

It remains unknown to me who erected this 1833 granite block monument at the murder site that I stumbled onto. Had this monument not caught my attention, I likely would have trekked through this remote hemlock stand without stopping, and never learned the story of Sally Cochran and what happened at this spot almost 200 years ago. Could it have been Sally Cochran and not the granite block that called out to me gaining my attention as I was passing by that snowy morning?

A special thank-you to Leslie Lambert Rounds, author of the book, “I Have Struck Mrs. Cochran With a Stake,” for her assistance in researching this story.