13 minute read

Moonlight Murders on Smuttynose Island WHAT REALLY HAPPENED 150 YEARS AGO?

BY J. DENNIS ROBINSON

ILLUSTRATION BY FOTOKITA

t is a grim anniversary. On March 5, 1873, a down-and-out Prussian fisherman stole a small wooden boat from a Portsmouth, New Hampshire, dock and rowed to the Isles of Shoals. In mild weather on calm seas, lit by a rising moon and urged forward by a powerful tide, Louis Wagner hauled on the wooden oars, blistering his already calloused hands. More than $600, three times what he could make in a year baiting hooks and hauling trawl lines, was waiting for him on Smuttynose Island. What began as a bold robbery quickly devolved into a grisly double murder that, 150 years later, will not go away.

After seven years in America, Norwegian immigrant John Hontvet had his own schooner and a successful fishing business. John could afford to pay the transatlantic passage for his brother, Matthew, and for Maren Christensen, whom he married. By 1872 they were all living in a rented duplex on Smuttynose Island, just over the New Hampshire border in Maine. John had also brought over Karen Christensen, Maren's older sister. Karen was working as a maid at nearby Appledore Island, preparing the hotel for the coming tourist season.

In need of another crewman, John Hontvet hired Louis Wagner, who was allowed to live on the other side of the duplex. It was a bad idea. Wagner, aged 28, frequently complained that rheumatism prevented him from working. When Maren's brother, Ivan, and his wife, Anethe, arrived from Norway, Wagner was forced to move off the island. In the days leading up to the murder, Wagner was sharing a small room with two other men in a cheap boarding house on the Portsmouth waterfront. His rent was six weeks overdue and, according to another fisherman, Wagner had to borrow 35 cents just to buy tobacco.

On March 5, Wagner was lingering on the docks in the city's gritty South End neighborhood (now Prescott Park) when the Hontvet schooner Clara Bella arrived.

"You have been quite a stranger to me," Wagner told John Hontvet. "I have not seen you since three weeks before Christmas."

Wagner appeared to be annoyed that Ivan was working with Matthew and John. It was Ivan, after all, whose arrival from Norway had put an end to Wagner's free room and board on Smuttynose Island. Unaware of how des- perate Wagner had become, John Hontvet foolishly revealed he had saved $600 to buy a new boat. According to John's later trial testimony, Wagner asked three times if the men planned to return to Smuttynose that night. Feigning concern, Wagner worried whether Maren and Anethe would be safe all alone on the island at night.

And here we must insert a critical detail. Since the 1620s, men who fished off the Isles of Shoals had been doing it the oldfashioned way: with a few hooks on a line. John Hontvet was a local pioneer in the high-tech "tub trawl" technique. Long wires with as many as a thousand hooks were laboriously baited by hand and curled into a wooden tub. Crewmen then uncoiled the baited lines into the sea and marked the location with floating buoys. The resulting catch could be enormously profitable. But the operation required so much bait that John had ordered it shipped to Portsmouth from Boston by train.

Had the train arrived on time, Karen and Anethe Christensen might have lived full lives and we would not know their killer’s name. But the delivery, John learned, would not arrive until midnight. Wagner said he would be back later to help bait trawls. He needed the cash. John's crew worked through the night, but Wagner never returned.

Crime & Capture

No one saw Louis Wagner steal David Burke’s dory from the dock at the base of Pickering Street in the city’s South End. No one saw him beach his boat near where a granite breakwater now connects Smuttynose to Cedar Island and Star Island across Gosport Harbor. The thief in the night likely planned to slip silently through what he knew was an unlocked door and into the warm Hontvet kitchen where Maren had served him many meals. So far, so good.

Wagner knew the island well. But he did not know Karen Christensen had quarreled with Eliza Laighton, owner of the Appledore Hotel, and been fired. Karen was sleeping on a makeshift bed near the stove in the kitchen. Startled by Wagner's entrance, she cried out. For his plan to work, Wagner knew, he could not be identified. In the darkness, he grabbed a heavy wooden chair and brought it down hard on the moonlit figure.

The commotion woke Maren and Anethe who were sleeping in the downstairs bedroom. Ringe, the family dog, barked. Karen, battered and terrified, managed to join her sister and sister-in-law in the bedroom. family owned the Appledore Hotel, rushed to Maren's aid. It was Celia's family who had rented the house on Smuttynose to the Hontvets, and it was Celia's mother, Eliza, who had fired Karen Christensen two weeks earlier. In shock, Maren could only repeat, "Louis, Louis, Louis."

Trapped by an unseen monster, the three women huddled together in the bedroom. When Anethe, the youngest, tried to escape out the window, a familiar man loomed up from the darkness. "Louis, Louis, Louis!" she cried, and fell silent.

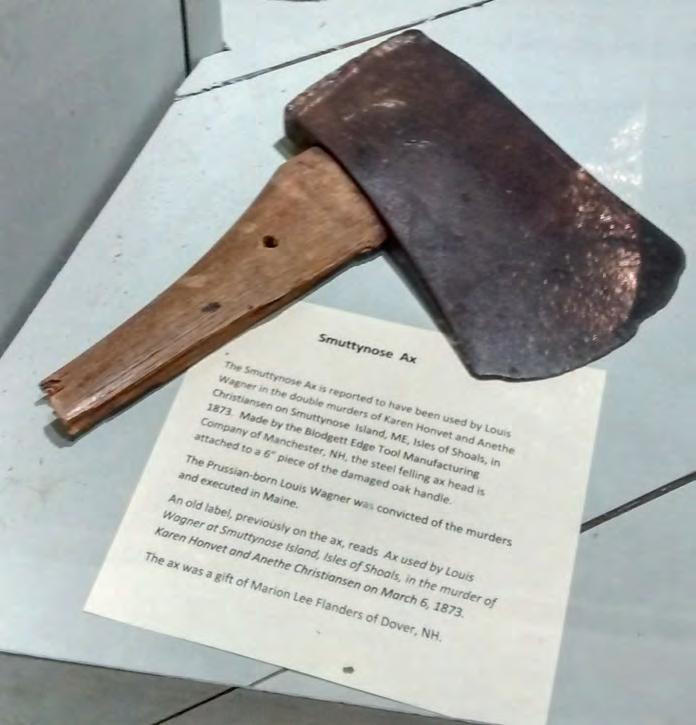

Maren Hontvet could not see the face of the shadowy figure that struck Anethe with an ax, but she knew the name. It could only be Louis Wagner. Injured and paralyzed with fear, Karen could not move. As the dark shape rounded the corner of the house, heading back inside, Maren climbed out the window and ran. Hiding among the icy rocks, she heard Karen's final scream.

There were close to a dozen empty buildings on Smuttynose in 1873, including a dilapidated old hotel, but no other residents. Wagner searched for Maren for hours, evidenced by his size 11 boot prints in the snow. The robber-turned-killer washed up by the island well. He searched without success for John Hontvet's hidden fortune, leaving bloody handprints in an age before CSI-style testing. He dragged Anethe's body into the kitchen and ate a meal before rowing back to the mainland.

Arriving at dawn, exhausted, Wagner stashed his stolen boat at New Castle Island, at a spot the locals called Devil's Den. A year later, in 1874, the newly constructed Wentworth Hotel opened nearby. Windburned, coated in ice and spots of blood, he trudged roughly three miles back to the Johnson boarding house in Portsmouth. Witnesses would later identify him at "the trial of the century."

Despite his frightful condition (he swore the blood was fish guts) and lack of sleep, Louis Wagner hopped the morning train to Boston. There he paid for a haircut and shaved off his beard. He bought a set of used clothes and boots and chatted incoherently with a local prostitute. Having been penniless the previous day, Wagner spent between $15 and $16 — the same amount missing from the Hontvet house — before he was broke again. Stopping at a boarding house where he had once lived, Wagner begged owner Katherine Brown for a free meal. When he fell asleep near the warm kitchen stove, Mrs. Brown alerted the police. By the time he had eaten dinner, Wagner was under arrest.

Maren Hontvet, meanwhile, had survived the night. A Norwegian family living on Appledore Island spotted and rescued her on the morning of March 6.

The crew of the Clara Bella, landing at Smuttynose, discovered the horrific scene. Ivan Christensen, cradling the body of his wife Anethe, was overcome by grief. After visiting Maren, John Hontvet delivered a description of the killer to the local police.

By 8:45 that night, a Portsmouth officer had traveled to Boston to collect the prisoner.

"That’s the man, but perhaps the wrong one," Wagner retorted. He would assert his innocence even on the gallows.

By the time the prisoner arrived back in Portsmouth, on March 7, a "hooting mob" had assembled at the train station. The crowd chanted: "Lynch him! Kill him! String him up!" Police officers drew their revolvers in defense and, assisted by marines from the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, Wagner was safely escorted through city streets and locked up. Within an hour, the crew of the Clara Bella entered the police station through a side door.

"Oh, damn you murderer!" John Hontvet cursed Wagner. "You kill my wife’s sister and her brother’s wife."

Laighton Thaxter, a famous Victorian poet whose

Celia

"That’s the man we are looking for," the Portsmouth officer told his Boston colleagues. "Gentlemen, you have got a murderer."

"Johnny, you are mistaken,” Wagner replied, gripping the jailhouse bars with his heavily blistered hands. “I hope you will find the right man who done it."

"I got him," John said. "Hanging is too good for you, and Hell is too good for you. You ought to be cut to pieces and put on to fish-hooks."

This dialogue, we should be aware, comes from Wagner’s testimony. At trial, in his defense, the prisoner would blame John Hontvet for leaving the women alone and unprotected. Later, while on death row, he repeatedly claimed that Maren Hontvet was the killer.

Trial & Execution

By the next day, Louis Wagner was a fullfledged celebrity. Hundreds of citizens — women and children included — crowded the jailhouse to catch a glimpse of the prisoner. Many were shocked to find him a gentle and attractive young man who seemed to enjoy the attention, especially from the ladies. Dueling Portsmouth daily newspapers immediately took sides over the prisoner's guilt or innocence.

Under interrogation, Wagner spun a detailed alibi. Although known to avoid alcohol, he claimed he had gotten drunk at a saloon, the name and location of which he could not recall. The beer made him sick, he said. He slipped and fell, then spent much of the night lying outdoors in the streets of Portsmouth, although he was not certain where. He later returned to bait trawls with John Hontvet, Wagner explained, but fell asleep, unseen, in an adjoining room. The prisoner denied having stuffed a bloody shirt down the privy after returning to his boarding house. An analysis of the stolen dory showed the wooden thole pins connected to the oarlocks had been worn down in a single night.

"The chain of evidence seems to be tightly closing around Wagner as the murderer," the weekly Portsmouth Journal concluded.

Local outrage flared when, 60 hours after the murder, the bodies of the two women arrived from the Isles of Shoals. The head of 25-year-old Anethe Christensen, the coroner reported, had been "terribly hacked to pieces." Discovered under a bed in what had been Wagner's side of the duplex, Karen Christensen, 39, had been bludgeoned and strangled.

George Yeaton, the prosecuting attorney, was a polished and cultivated legal mind.

Since Smuttynose Island was technically in Maine, Yeaton smuggled his notorious suspect through a second Portsmouth lynch mob and across the Piscataqua River by train. Wagner found himself in a comfortable, newly constructed prison in the York County "shire" village of Alfred, Maine. Newspapers coast-to-coast feverishly covered his nineday trial.

"He possesses one of those faces to which you would naturally take a liking, though there is about it a weak appearance, which grows upon you, the more you look upon him," the Portland Press reported.

The prisoner continued to plead his innocence, often bursting into tears that shocked Victorian audiences. Even Celia Thaxter later admitted that Wagner’s demeanor in jail and at trial "was a wonderful piece of acting" that "really inspired people with doubt as to his guilt." Why would he hurt the Hontvets? They were his best friends, he claimed.

"If I wanted money," Wagner explained, "I knew every trunk in the house; knew Hontvet was in Portsmouth; could have gone there and taken the money if they were asleep without murdering them." In Wagner's twisted universe, the victims were to blame for waking up and spoiling his perfect robbery plan.

Wagner's court-appointed lawyers included Col. Rufus Tapley, a former judge from Maine, and Max Fischacher, a Jewish attorney from Boston. But his dream team had no case. Witness after witness confirmed seeing the prisoner on the road from New Castle the morning after the massacre. No one had seen him in Portsmouth for 11 hours. His flight to Boston, his bloody clothes, the stolen boat and Maren Hontvet's stirring testimony at trial built a damning circumstantial case.

Twelve male jurors deliberated for 55 minutes before returning a guilty verdict. Back in the courtroom a week later, Wagner was sentenced to death by hanging. He returned calmly to his cell in shackles. That night, he picked the lock on his cell door and disappeared, taking two accomplices with him.

"The report of Wagner’s escape at Alfred caused much excitement and no little indignation," according to the Portsmouth Evening Times. Three days later, the convicted ax murderer was recaptured near Gonic, New Hampshire. He was not running away, the prisoner claimed, but simply needed some exercise. Suddenly converted to Christianity, Wagner often announced that God would not allow an innocent man to be executed.

Two years later, Louis Wagner stood on the gallows at Thomaston, Maine, next to another ax murderer. John True Gordon had killed his brother, his sister-in-law and their 17-month-old daughter as they slept in the family bed. He then poured kerosene on the bodies and set fire to their farmhouse. Gordon had confessed and even attempted suicide, but Wagner continued to claim his innocence. As the local sheriff placed a black hood over Wagner's head, the Smuttynose murderer gave a final pitying glance at his companion. "Good and poor John, we’re gone," he said.

Fact, Fiction & Fake News

Wagner was biding his final days on death row when Celia Thaxter's essay, "A Memorable Murder," appeared in the prestigious Atlantic Monthly magazine. Arguably Celia's best work, the story of Karen and Anethe scandalized many readers who considered the subject unfit for a female writer.

"Maren and her husband still live blameless lives," Celia wrote, "with the little dog Ringe, in a new home they have made for themselves in Portsmouth." In April 1876, John launched his new schooner, named Mary S. Hontvet after his wife. He was still at sea a month later when a "startling rumor" appeared in local newspapers.

According to an unnamed source, a dying "Swedish" woman had confessed to killing her sister and her sister-in-law on Smuttynose Island. Although quickly retracted and debunked, the cruel hoax was a terrible blow to the Hontvets.

The couple's only child, Clara Eleanor Hontvet, was born in Portsmouth on January 6, 1877, when Maren was 42. Mother and child traveled to a village near Oslo some time in the early 1880s. Maren Sebeille Hontvet died in Norway on June 24, 1887, more than 10 years after the fraudulent deathbed confession had appeared. After surviving several harrowing shipwrecks, John Christian Hontvet remarried and turned to farming in Portsmouth until his death in 1904.

In 1926, Harvard-educated librarian Edmund Pearson re-opened the case in his book “Murder at Smutty Nose and Other Murders.” Considered the father of the "true crime" genre, Pearson saw Louis Wagner as the quintessential social deviant. The poor, frustrated and friendless fisherman was outwardly attractive, yet "as dangerous as a rattlesnake," Pearson wrote. Although convinced of Wagner's guilt, Pearson's book stirred the pot for a new generation of armchair detectives.

Instead of silencing skeptics with the truth, “Murder at Smutty Nose” seemed to summon a coven of conspiracy theorists. It was impossible, skeptics insisted, for Wagner to row to the Shoals and back. John Hontvet, for the record, testified that he had made the trip in a rowboat at least 50 times. Kayakers regularly row the distance today. In a 21st century reenactment, a 75-year-old businessman in a replica wooden boat covered the distance easily in 2 hours and 14 minutes. Wagner, a strapping 28-year-old dory fisherman, was gone for 11 hours.

A wave of pro-Wagnerites, most who knew only the bare bones of the story, seized on the killer's claim that Maren was to blame. To Edmund Pearson, such blind faith in the face of so much evidence was criminal behavior.

"To seek to clear Louis Wagner at the expense of Maren Hontvet is to engage in a second hunting of that wretched woman," Pearson wrote. "It is only a little less despicable than the pursuit which took place over the rocks of the island on that winter night."

Novelist Anita Shreve took the "Marendid-it theory" to new heights. Shreve deftly fictionalized details from Celia Thaxter, Edmund Pearson and the Wagner trial transcript to create her 1997 bestseller, “The Weight of Water.” The novel included an invented deathbed confession letter from Maren, spawning yet another generation of conspiracy theorists. Academy Award–winning director Kathryn Bigelow adapted “The Weight of Water” into a Hollywood film of the same name. The $16-million mystery thriller starring Sean Penn bombed at the box office, bringing in an estimated $321,279 worldwide.

The debate drags on. Can an author or filmmaker flip history upside down, turning real life victims like Maren Hontvet into murderers? University of New Hampshire professor Larry Robertson posed this question to readers of the Portsmouth Herald during the release of the film. Technically, yes. Fiction writers have been murdering facts since Shakespeare wrote his ofteninaccurate history plays based on the British monarchy.

Could someone else be guilty? Wagner offered a number of alternate theories while awaiting execution — a sailor from a “mystery ship” or a carpenter building the hotel on Star Island, perhaps. A Maine professor argued that blood seen on Maren’s nightgown after her rescue was a smoking gun. For the record, after discovering Anethe’s body, the surviving victim had bloodied her hands and bare feet on the sharp island rocks. A local cruise ship captain, without evidence, cruelly suggested that Celia Thaxter’s mentally challenged son, Karl, was to blame.

Was Louis Wagner a sociopath? The concept was unknown in the Victorian era when electric lights were still a decade in the future. But based on his actions and many published media interviews, Wagner ticks all the boxes. He was glib, grandiose, opportunistic, boastful, superficially charming, impulsive and cunning. He was also a pathological liar, had no long-term goals or friends and exhibited no remorse or responsibility for his actions.

"The sociopathic mind makes excuses for everything," says criminal law instructor Terry Kalil, today a steward of Smuttynose Island, "because they cannot admit that another person is right." Everything that went wrong in Wagner's world was someone else's fault.

And yet, like the Hontvets, we are hopelessly drawn into Wagner’s web. The tale of a double homicide on a moonlit island has been transformed into a bestseller, a film, a graphic novel, a true crime documentary, podcasts, a stage play, research papers, countless articles, even a ballet and a virtual reality movie.

No photograph of Karen or Anethe Christensen survives. They are pictured, inevitably, as two conjoined tombstones in Portsmouth's South Cemetery. It is the killer, all too often, who dominates the headlines, leaving us with unanswerable questions and a voice from the grave, crying, "Louis, Louis, Louis!" NH

J. Dennis Robinson has been a volunteer steward of the privately owned Smuttynose Island for over two decades. He is the author of “Mystery on the Isles of Shoals: Closing the Case on the Smuttynose Ax Murders of 1873” and “Under the Isles of Shoals: Archaeology & Discovery on Smuttynose Island.” His latest books and articles can be seen online at jdennisrobinson.com.