4 minute read

Pull And Be Damned!

Spectators saw what 50 tons of dynamite could do in a heartbeat

BY MARSHALL HUDSON / PHOTOS COURTESY NH STATE ARCHIVES

The Ogre called. He had some old photographs I needed to see. The Ogre enjoys historic research and spends so much time in the vaults that we’ve nicknamed him “The Ogre Who Lives Beneath the Archives.” The last time the Ogre called, he had found a photo that launched me on a search for a lost bridge over a bridge. This time his photos would send me searching for a hole in the ocean. One that isn’t there anymore. How difficult could that be?

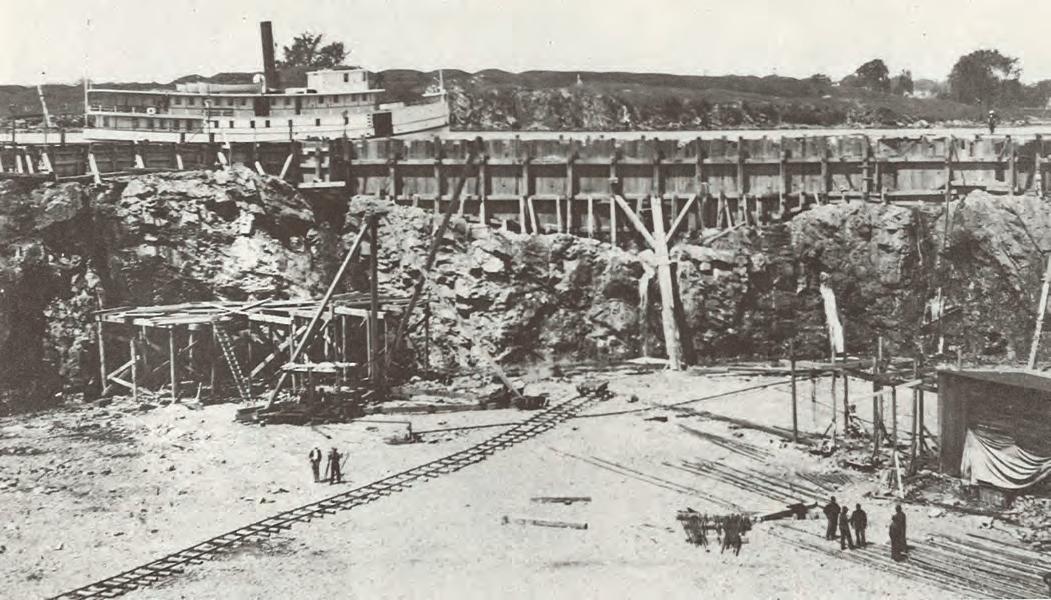

The photos showed a large open pit mine or rock quarry. In the foreground, ant size men work alongside trolley tracks. Shanty buildings on the floor of the pit cover a boiler for operating a steam powered rock drill. None of this is unusual for granite laden New Hampshire. What is unusual is at the top of the photo. The men are working some 60 feet below sea level as a passenger steamship motors by the excavation site. The ocean is held back only by wooden planks, precariously propped and braced.

Close-up photos depict unsmiling brave men in bib overalls and slouch hats holding sledgehammers or operating drills. Behind them, sheer rock cliffs rise above their heads with the tenuous wooden plank cofferdam atop the cliffs. A long-distance photo shows that the cofferdam is horseshoe shaped and anchored to the shoreline on both ends but extends out into deep water in the middle. Off in the distance, I think I recognize the old Portsmouth Naval Prison, a valuable clue in tracking down the answers to these curious pictures. I made a phone call and arranged a road trip and lunch date with my friend, Carol White, New Castle Historical Society Board Member and Town Historian.

“That’s Henderson’s Point,” White says. “Local tour guides sometimes incorrectly refer to it as Pull And Be Damned Point, which is actually situated on the other side of the river.” Pull And Be Damned Point was a ledge outcrop that extended north out into the Piscataqua off Goat Island in New Castle. On the opposite shore, Henderson’s Point extended into the river off the south side of Seavey Island in Kittery, Maine. White tells me that the Pull And Be Damned moniker is sometimes incorrectly applied to both sides of the river at this location. The opposing ledge protrusions required ships to zigzag from shore to shore at a sharp bend in the river, presenting a hazardous challenge for sailing vessels when the wind or tide wasn’t cooperative. This chokepoint also squeezed this section of the river creating fast water that frustrated sailors in rowboats who would row (pull) with all their might and not go anywhere (be damned).

In the mid-1800s, the Portsmouth Navy Yard was looking to expand and considering adding a major drydock for shipbuilding and repairs. Portsmouth Harbor was a deep port that didn’t ice-up in the winter, but there were those nasty ledge outcrops in the Piscataqua to navigate around. A study by Navy engineers concluded that Pull And Be Damned Point could wait, but Henderson’s Point had to go. The rocky point was about 550 feet long and 750 feet wide and all of it would need to be removed to a depth at least 35 feet below the level of the lowest tide. The solution to the dilemma of how to remove this spit of solid rock below sea level was … dynamite. Lots of dynamite and one big blast.

With demolition money from the Navy, the destruction of Henderson’s Point began in 1902. By 1904, the initial excavation was done. Engineers had blasted and excavated 500,000 tons of rock down the centerline of the point. The result was a horseshoe-shaped crater with sheer rock walls 60 feet high. Around the horseshoe’s perimeter a wooden cofferdam was erected to hold back the tide. Inside, the hollowed-out Henderson’s Point workers prepared for the final blast, which would remove the entire perimeter in one spectacular explosion.

Holes in the ledge were drilled 70-to80 feet deep and filled with special sticks of dynamite made to fit the holes. The pit would be flooded prior to the explosion to muffle the shock and slow the airborne debris. This meant some of the dynamite would be underwater for weeks leading up to the big bang, so the sticks were wrapped in layers of paraffin for waterproofing. Two hundred tons of dynamite were used, and special electrical systems were installed to ensure that the final 50 tons of dynamite would ignite simultaneously. The blast was scheduled for 4 p.m. on July 22, 1905. Newspapers warned of the pending explosion and recommended people open their doors and windows and remove brica-brac items from shelves. Ladies “in an interesting condition” (pregnant) were transported to safety in Rye. Camera companies promoted their wares encouraging people to photograph the historic explosion. Some

Portsmouth and New Castle residents left their homes fearing falling rocks, water surge or shock wave. Conversely, special trains brought in tourists eager to see Henderson’s Point blown off the map. Opponents ran editorials expressing their dislike for the project, alleging it wasn’t necessary, wouldn’t work, cost too much and might have unanticipated consequences including throwing the earth off its orbital axis.

The explosion took only seconds, and at 4:10 p.m., a spout of water, rocks and timbers shot 150 feet into the air. Spectators saw what 50 tons of dynamite could do in a heartbeat. Henderson’s Point was blown to bits and scattered about Portsmouth Harbor. The horseshoe-shaped cofferdam shattered as planned and the rock beneath it crumbled. Fears that the earth might crack or be knocked off its axis proved unfounded. Falling rock did not cause damage or injure spectators as some had predicted. The explosion was touted as a success by the newspapers and proud Navy engineers.

Pull And Be Damned Point had to wait another 90 years before it was partially removed. Carol White shared with me a newspaper clipping from 1900 mocking legislation which would have changed the name of Pull And Be Damned Point to “Goat Island Ledge” or “Profanity Point” to avoid offending sensitive ears. The clipping indicates that the legislation failed. The irreverent name would remain. Other than some newspaper clippings and warnings on old maps, little remains today of Pull And Be Damned Point or Henderson’s Point’s story of a big blast. Thankfully, some curious old photos exist, and they were found by The Ogre Who Lives Beneath the Archives. NH