2 minute read

Civil Warrior

PHOTO AND INTERVIEW BY DAVID MENDELSOHN

History is a record of where we’ve been and what we’ve done, but too often seems either cold or subjective. Despite heroic attempts at neutrality, it appears as a narrative told through a selective vision; a landscape filtered by another’s lens. Meet Marek Bennett, who takes an alternative path into yesterday. A specialty area of his is America’s greatest and ugliest struggle, now known ironically as the Civil War. By illustrating the diaries and letters of those who have actually lived it, he brings their voices to the front of the choir. With his books, workshops, cartoons — and his skill playing an authentic Civil War-era banjo — Bennett ushers the past into the present and makes it lively, livable and clear. Yep. It’s about time.

History fascinates me because it’s at least two things at once. On the one hand, it’s the stories of people, and on the other hand, it’s a reflection of what we see in those stories, now.

I like that challenge — the balancing act between old voices and our constant revision (and hopefully improving understanding) of what they mean to us.

My hometown of Henniker had a population of about 1,500 people in 1860. The local historical society has documented over 120 men from town who served in the Civil War. That’s a huge part of the town — an immense moment in local history. It changed our local history forever after.

NH Historical Society (where the adjacent photo was taken) has this great big building to hold artifacts and documents. But for every voice that’s represented in these archives, there are many, many voices that have been left out of the historical record, either accidentally or on purpose.

A Union soldier like Henniker’s Freeman Colby (whose diaries Bennett illustrates) came home to a community that could preserve his written account. There’s a sort of cultural ecosystem there that allows his story to survive.

But there were so many other people whose stories touch Colby’s. For example, the hospital nurses, his fellow soldiers, the refugees from slavery that he met and taught — many of them did not have access to such archives and supports.

To really understand our history, we need to put all these voices into context and conversation. “Marginalized” voices often aren’t at the “margins” at all. They’re often right there at the heart of things!

Cartooning is the art of drawing as little as possible to get the maximum effect. I call my style “Epic Stick-Figure Adventure” because I draw minimally — leaving out details that are not absolutely essential to the narrative — but on an epic storytelling scale.

I’ve been drawing the Freeman Colby Series for 10 years now, completing three volumes that span from 1861 to May of 1864. As I begin work on Volume Four, I’m really focused on getting these books out to as many people as possible, and building that community of readers of all ages.

When I do readings and meet my readers, I love that one reader might be 70 years old and the next reader might be 10 — both reading the actual text of 160-year-old letters! I love that the graphic novel format supports all kinds of engagement, so people can really dig into and enjoy the reading experience.

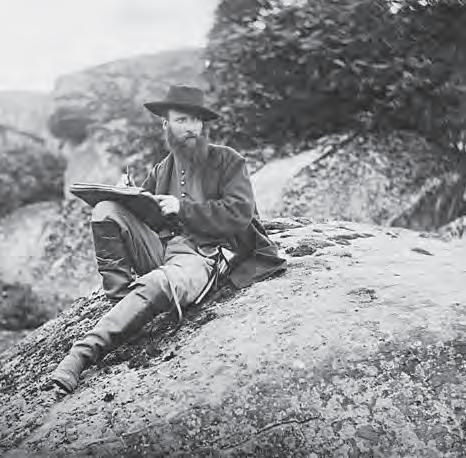

The (Sketch) Art of War

Among many artistic influences, Marek Bennett claims Alfred Waud (pictured left) as one of the greatest. Waud moved from battle to battle during the Civil War, sketching out the scenes and providing illustrations to Harper’s (many of which were compiled in books like the one featured). Bennett’s own sketches of history take a minimalist approach influenced by contemporary cartoon art, but — combined with his storytelling and based in original diaries and accounts — still pack a visceral historical punch.