15 minute read

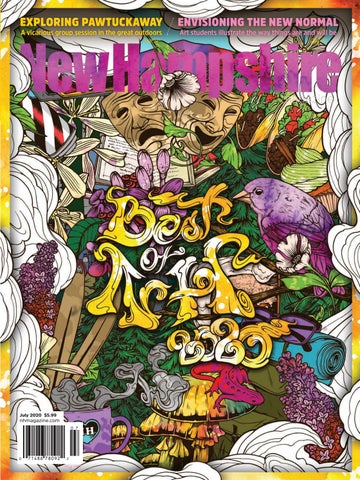

Where There’s a Will, There’s Pawtuckaway

A vicarious adventure with friends harking back to those carefree days before the pandemic, courtesy of The Explorers

By Jay Atkinson Photos by Joe Klementovich

Driving by the main entrance to Pawtuckaway State Park, I felt like one of the Neolithic agrarians who built Stonehenge, revisiting the site many years later.

On an unseasonably cold, gray morning, I was heading to meet my rugby pals at the Fundy boat ramp a couple miles away. Our plan was to mountain bike approximately four miles over rough ground to the boulder field, where we’d do some rock climbing and scrambling. In addition to these new adventures, my trip to Pawtuckaway was a nostalgic journey into the past.

Every summer when I was a kid, my parents reserved a campsite on Pawtuckaway’s Horse Island, where my four siblings and I spent our time biking, swimming, fishing, and doing a whole lot of nothing. Those are some of my happiest memories, of long summer days, throwing a baseball around and grilling hamburgers. So driving toward the rendezvous point, I felt a pang of sorts — like those nomadic hunter-gatherers that looked upon their earlier haunts with reverence, and a palpable sense of mystery.

The name Pawtuckaway is derived from the Abenaki, and is variously translated as “place of the big buck,” “fall in the river” and “clear shallow river.” Located in Rockingham County, the 5,500-acre park includes 192 campsites along the shore of 800-acre Pawtuckaway Lake. Apart from the campground, the distinguishing feature of the landscape is an abundance of whaleback hills, or drumlins, left behind by retreating glaciers. The main camping season extends from Memorial Day to Columbus Day, although the park is typically open year-round for responsible hiking, biking, fishing, cross-country skiing and other sporting ventures.

The weather that morning resembled that of England’s Salisbury Plain — gray, damp, and in the low 40s. At the end of a long dirt road, I found photographer Joe Klementovich and Bridget Freudenberger waiting in the boat ramp parking lot.

“You’re three minutes late,” said Joe, grinning at me.

Soon after, Randy Reis and Jason Massa arrived, as well as my regular “swim buddy,” Tammi Wilson of Pelham. (Chris Pierce and his children Will and Kaya were meeting us at noon, after Piercey’s soccer game.) In the parking lot, we changed into cycling togs, hoisted our bikes onto the gravel, and filled the pockets of our hydration packs with energy bars, mini first aid kits, etc.

Jason produced a trail map and ran his finger along the dotted line of the Fundy trail, skirting the cove of the same name. The Fundy trail intersects with the Shaw trail, which meanders northwest through some wetlands, and, by the look of the topography, over a variety of rugged terrain.

A veteran endurance athlete and mountain bike racer, Jason folded up the map, replacing it in his pack with a look of satisfaction, like Gen. George S. Patton embarking upon the Sicily campaign. Jason nearly yawned as he mounted his bike while I stifled a laugh, following my old buddy and his dog, the quiet and steady Dozer, over a wooden bridge onto the Fundy trail.

There’s a funny scene in Quentin Tarantino’s 2009 WWII black comedy, “Inglourious Basterds,” where American commandos led by Lt. Aldo Raine (Brad Pitt’s character), hatch a desperate plan to kill members of the Nazi high command. Raine decides that he and two other soldiers will pose as Italian filmmakers, on hand for the premiere of Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda film, “Nation’s Pride.”

Jason Mass is all smiles when he’s going fast on his mountain bike, pushing the group to get there faster.

But the GIs are at a disadvantage since Raine, who has the best grasp of Italian, speaks very little of it. His two comrades know even less. Over their objections, Raine points to one of his men, saying, “Second best,” and the other, “Third best.”

Dumbfounded, the soldier protests that he doesn’t speak Italian at all. “Like I said, third best,” Raine says.

As soon as we flowed onto the Shaw trail, it grew hilly, rocky, muddy and narrow. Although there were six of us, in the lingua franca of mountain biking I was “third best,” figuratively speaking. Rolling along beneath the canopy of trees, Jason shot ahead, mountain goat-style, clearing fallen trees and tricky-trotting through muddy bogs on the ragged patio of stones.

Hopping rocks to cross a swollen brook, I found myself hiking the bike uphill. At the top of a rocky drumlin, I climbed into the saddle and went swooping down a trail webbed with roots and boulders. At the conclusion of the hill, the trail turned black with mud, angling sharply westward, through a grove of 6-foot white pines with rubbery trunks.

Zipping along at breakneck speed, I felt my front tire wedge itself between two football-sized rocks. The abruptness of the stop flung me off my bike, and I went hurtling to the left with little expectation of a positive outcome.

My left shoulder crashed against one of the young pine trees, my left hip against a neighboring tree. The trunks were skinny and flexible, and in a marvelous bit of physics, the trees sprang back and I landed on my feet — the Fosbury Flop of Pawtuckaway — letting out a whoop that would have frightened the Druids and Celts of yesteryear.

For another long stretch, the trail and a meandering stream were practically indistinguishable, and I was forced to shoulder my bike over downed trees and piles of brush. The dipping, rising, twisting track had strung out the group, but I knew Tammi was behind me, struggling with her hybrid bike, which wasn’t suited for all these obstacles. But I also knew she wouldn’t give up, so here and there I stopped in a leafy glade or atop a rocky promontory. If she didn’t appear for a length of time, I cupped my hands and sang out, and she hollered back.

Finally, after two hours of grinding along, Tammi caught up and we reached Round Pond. The trail hugged the bank, providing us with amazing views of the huge boulders sticking up from the pond and huddled alongshore. Known as “glacial erratics,” some of the boulders resembled loaves cut in half, and others were rounded and smooth, shaped by winds and receding ice.

From mountain biker to hiker, Bridget takes a look at the groups next challenge — rock climbing.

Near the intersection of Round Pond Road and the Boulder trail, Tammi and I reconvened with the others. A rock climber with 30 years of experience, Joe had brought along ropes and other gear. But Randy, Jason and I needed a change of clothes and something to eat, so we rode back to the boat ramp via Deerfield Road. Jason was pedaling slowly to shield Dozer from passing cars, so Randy and I went ahead.

Randy “Slippery” Reis, the old Fordham tailback and my longtime rugby teammate, is a wry-tempered fellow with a sneaky wit. He’s married to his law partner, Kimberly, and has two grown daughters. While we cruised along Fundy Road toward the parking lot, we made way for an SUV coming toward us.

Then we realized it was Piercey and the kids. Piercey rolled down his window. “Hey, what’s up?” “Just riding around aimlessly,” I said. Randy and I leaned over to fist bump 10-year-old Will and 14-year-old Kaya through the window. Following a hasty lunch, we returned to Round Pond Road and hiked in a couple miles to meet the others on the Boulder trail. After carrying in the ropes and hardware, Joe was preparing to climb a long, gray shelf of rock called Lower Slab. It rose 40 or fifty 50 in the midst of a stately hemlock forest — the middle section tapering to stacks of boulders on either end.

A hundred feet downslope from Lower Slab, there was a little pond that contained an impressive beaver dam and lodge jutting up from the water. The North American beaver, or Castor canadensis, is both a rodent and a “gnawer,” related to squirrels, porcupines and rats. Better educated than their unruly cousins, beavers are well-trained engineers, and several half-chewed trees were evidence of their technical skill.

Our party was at the bottom of the slab for 5 or 10 minutes, talking, hydrating, and helping with the gear, when Joe started up, free climbing until he could put in the hardware. Previously out of sight atop the cliff, another climber suddenly loomed over us, holding a rope.

Willem Pierce taking a swing after giving a solid go on a steep hand crack

In a sarcastic tone of voice, the climber accused Joe of breaking etiquette by taking over a section of Lower Slab already in use. More than a little surprised, Joe explained that we’d been there for some time, and no other climber had appeared or spoken up. Nor had other climbers left any gear, or a member of their party, at the base of the rock to make their claim visible.

Joe also noted that he was partway up the route when the other climber objected. Beyond that, anyone climbing up from the ground had priority over someone who wanted to toss down a rope, he said.

The other climber returned to the foot of the slab by a path that circled around behind, while Joe finished clambering to the top. Their positions now reversed, the other climber continued the harangue. “Look — I’m sorry,” Joe said, in a patient tone. “It doesn’t sound like you’re sorry,” said the irate climber. “You know you’re wrong, but you won’t admit it.”

Joe shrugged, and the other climber stalked off through the trees. My friends and I gave each other the eyeball, and looking at Randy, I said, “Jean-Paul Sartre was right — hell is other people.”

Fault, and the bottom of the slab was vertical and smooth, meaning I’d be straining my Achilles tendon from the get-go. So I begged off climbing with a rope, and explored the eastern side of Lower Slab, finding an irregular stack of boulders perfect for scrambling. By the time I reached the apex and walked back around, Randy was there, and led the way to a more vertical section.

I watched Randy’s progress, and when he reached the top, I started up the same route. Putting my back against a hemlock growing close to the slab, I spacewalked up the steep flat part of the rock. Then I shifted my weight as Randy had done, springing across to catch hold of a thin stone shelf. Wriggling up a narrow fissure in the rock, I got to the open end of the little chimney and had a rough time shifting out of there back onto the slab.

For half a minute, I was stuck, my chest heaving. It was a tactical problem, and I had to invent a creative solution.

Randy said, “You can go back down, and come up another way.”

Suddenly, I turned myself around in the chimney, pushing my hands downward on little protuberances in the rock and using my triceps to raise my seat onto the next boulder.

“Very innovative, Chet,” said Randy, using his nickname for me.

We arrived on top of the cliff just as Piercey finished a difficult ascent via the rope. “All right, brother!” I yelled, as Randy and I patted our left hand with the right in what’s commonly known as a “golf clap.”

Nearly eight hours after entering the park, Joe, Randy, Bridget, Piercey, Will, Kaya and I congregated in the muddy lot where we’d left our vehicles. The sky was iron gray, and a watery chill pooled around our ankles.

Piercey and the others cracked open beers while the kids tossed a Frisbee around, and Bridget and I chatted about open water swimming. A tall, good-natured banker from Colebrook, Bridget competes in endurance races and triathlons, but doesn’t like to swim in the ocean “because of the jellyfish.”

Waving my hand, I declared that the waters off Portsmouth and Rye were “too cold for jellyfish.”

Piercey rolled his eyes. “Jay, the jellyfish expert,” he said.

Pretending to be me, Randy said, “Hey, I’m a marine biologist.”

I was the only adult not drinking beer, although I took a slug from Randy’s Great North IPA, which is brewed in Manchester. ”That’s pretty good,” I said. “Wanna beer?” Piercey asked. “No thanks,” I said. “Why not? Is it a vegan thing?” “No, I’m good.” Piercey studied me with his philosophical gaze. Earlier he’d insisted that I try climbing with a rope, and I had said no.

“You don’t give in to peer pressure very easily,” said Piercey, lifting his chin in my direction.

“Thank you,” I said, raising my eyebrows at Randy.

Piercey shook his head. “You just tense up and get angry, like this.” He stretched his arms downward, flexing the muscles in his upper body. “’No, I’m not doing that’,” he growled.

There was a gale of laughter. “Why don’t you want a beer?” asked Piercey, more seriously this time.

I moved my shoulders a little. “There’s something else I wanna do.”

In the diminishing light, we embraced one another, said our goodbyes, and climbed into the vehicles. But I wasn’t ready to go home yet, although I was tired and hungry and rain seemed imminent. Instead of turning left out of the parking lot, I went the other way, driving toward the park’s main entrance.

Dusk was filtering down like a fine gray powder when I left my SUV in the empty lot near the main office. I stripped off my merino jersey, put on the last dry layer in my bag, and pulled my bike out of the vehicle.

Shivering in the wind, I snapped on my helmet and rode around the closed iron gate. Trees hemmed in the weathered asphalt on both sides, as I headed down the road toward the public beach and campground. It was only about a mile and a half but seemed longer, the road winding past Neals Cove, the black wall of trees allowing glimpses of the lake. I’d left my rain shell and phone in the car, and was pedaling as though the devil was chasing me.

Going up and down a trio of hills, I reached the campground, with the deserted beach and parking lot off to my right. The lake was turning silver in the twilight, flat and smooth like mercury, with the smell of woodsmoke drifting over from Horse Island. My breath coming in gasps, I slowed down, rubbernecking at the outbuildings and empty campsites.

Breaking from the tree line, I rode over the causeway separating Horse Island from the mainland. Soon I was rolling onto the bristling hump of land that includes Pawtuckaway’s most coveted sites. In the chill, the silence, and the encroaching darkness, I felt a keen sense of familiarity, even a homecoming of sorts.

When we were growing up, we spent my Dad’s vacation camping in the White Mountains, or at Hermit Island in Maine. Then we drove home to Methuen, and my parents, Jim and Lois, booked another two weeks at Pawtuckaway. It didn’t occur to me at the time, but their desire to have us spend a month outdoors came with a few sacrifices. (For instance, my mother loved my Dad more than she did camping.)

Camping at Pawtuckaway allowed my Dad to commute to his modest insurance office in the town square, returning to the campground each evening. My father was a big man, just under six feet and, back then, 240 pounds or so. He loved hiking and fishing and huge bonfires. To save time on weekday mornings, he began cultivating the silver-trimmed beard that would become his trademark.

Now, turning onto the island, I braked in front of site No. 3. A few early season campers were spread along the road, but No. 3 was vacant. It’s a picturesque little spot — my Dad’s favorite, as I recalled.

A gravel driveway ran slightly downhill to a giant, flat-sided boulder that would reflect the heat from our campfires. On either side of the rock, the water’s edge was 20 feet away, where my Dad would cast a line after supper, forgetting about the premiums and deductibles that occupied his day.

Quickly descending the ladder of years, I was transported back to playing catch with my cousin Dave Crane, fishing along the shoreline, and, in my teens, going for long runs through the campground, training for hockey and soccer and rugby.

But gazing at site No. 3, one particular evening came back to me. I was 12 or 13, my mother and younger siblings Jodie, Jill, Jamie and Patrick were busy with dinner, and my Dad had just arrived from the office. He changed into jeans and a sweatshirt and brought out his transistor radio, which had a long antenna and a black leatherette case.

Retrieving a beer from the cooler, my Dad, known as “the Big Guy” to my hockey teammates, unfolded a lawn chair and tuned into the Red Sox game.

Jim Kaat, a cagey lefthander, was on the mound for the Twins, and Luis Tiant, known as “El Tiante” and one of my Dad’s favorite players, was pitching for the Sox. In the quiet of the evening, between the announcer’s call you could hear “Get your ice cream!” and “Hot dogs here!” from the vendors working the crowd at Fenway Park, the sound of the broadcast floating over the lake.

It’s funny the things you remember, with so many other days and nights lost forever. But as I came into the campsite with my ball and glove, my father smiled at me, raising his beer. Those were some of our best times together, and I never guessed they would end so soon.

The word “nostalgia” comes from Greek, derived from “nostos,” which translates to “a return” and “algios,” meaning “pain.” Gazing into site No. 3, I recalled that bittersweet moment, so sharp and clear, although my Dad’s been gone more than 30 years. While the sun dropped behind the hills, I considered my father’s love for the outdoors, and what it means to my life now. A chill ran up my bare legs, and I shook my head in wonder, mounted the saddle, and rode off in the gloom.

Randy Reis making his first attempt at rock climbing wearing an old pair of running shoes