5 minute read

On the front line

Moms who are essential workers during this crisis face difficult choices

BY KRYSTEN GODFREY MADDOCKS

With New Hampshire schools closed and remote learning continuing through the end of the school year, parents are juggling more now than ever. And it’s tougher still for those essential workers who must commute to their jobs at hospitals, police stations, grocery stores, banks or newsrooms. Some receive hazard pay and protective equipment for their work, while others do not. Not only are they potentially exposing themselves to COVID-19, but they worry about introducing the virus to their families.

While working on the front lines is par for the course in professions such as health care or law enforcement, it’s new territory for others. Even for those professionals used to working during a crisis, COVID-19 brings with it new challenges and fears.

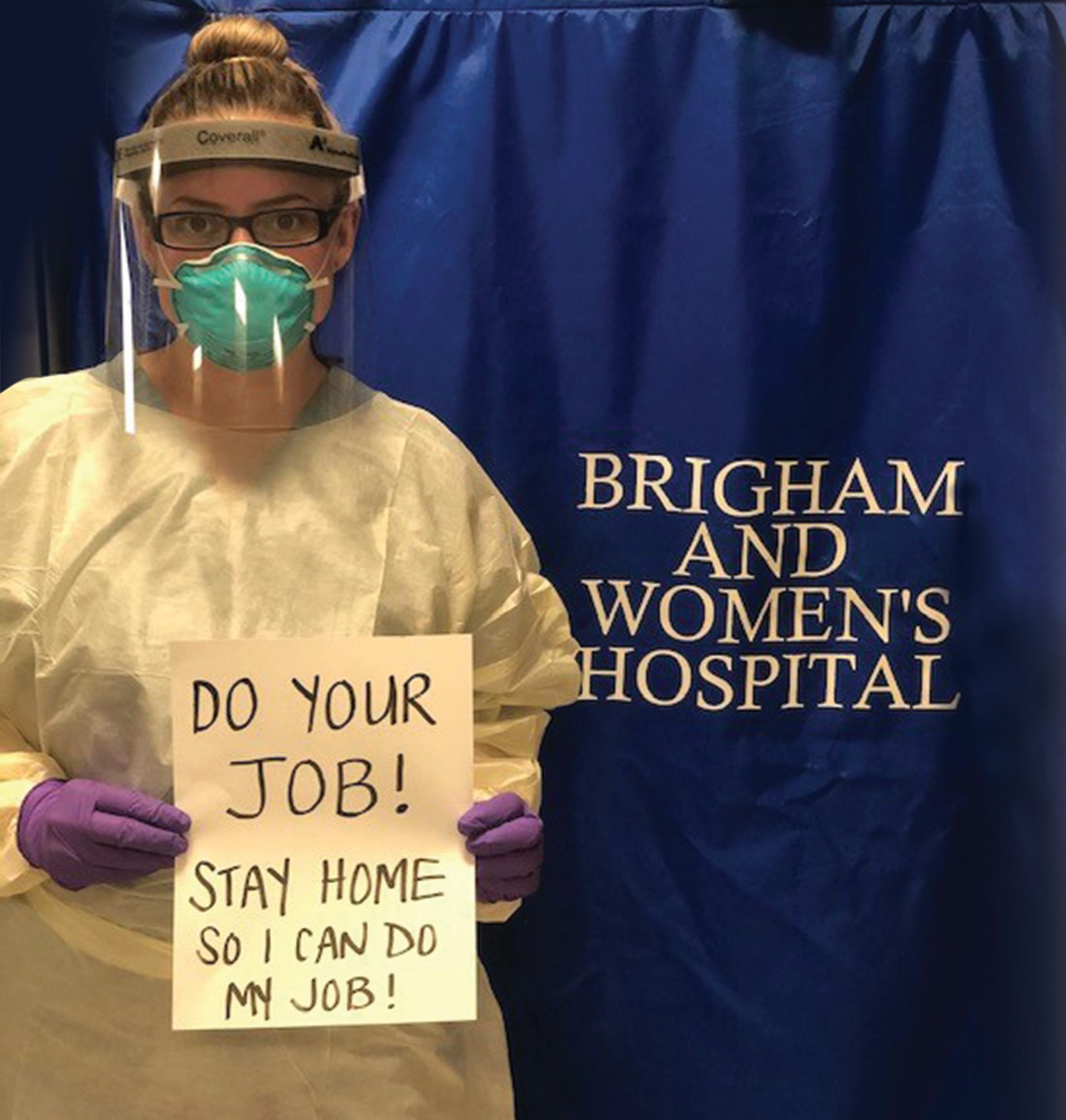

Kaylie Stewart of Londonderry is a registered nurse at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

COURTESY PHOTO

KAYLIE STEWART, 36, of Londonderry, is a registered nurse at Brigham and Women’s hospital in Boston, where she normally works in sur gical oncology but is now working in the special pathogens unit, which deals with COVID-19 patients.

Sometimes her shifts are cancelled, but lately it’s become very busy; she expects to work long shifts in the weeks ahead. Thankfully, her husband works full-time from home to watch their two children Adelaide, 5, and Shea, 3. Adelaide, who is in kindergarten, is participating in remote learning.

“We do the best we can on my days off,” Stewart said. “Her teachers are amazing and have been so supportive and under standing of our situation.”

Like many moms in the same situation, Stewart said that she feels a pull between caring for her patients, coworkers, and family.

“I am stuck in this weird place of needing to protect my family but also needing to do my job,” she said.

Lindsay Matrumalo of Sandown manages a busy veternarian hospital in Salem.

COURTESY PHOTO

LINDSAY MATRUMALO, 32, of Sandown, reports to work at a busy veteri nary hospital in Salem. Although her hospital doesn’t care for people, it ensures that animals with emergency medical issues are treated.

As a busy practice manager, Matrumalo schedules staff and appointments, manag es business operations like payroll and accounts payable and receivable, and occasionally assists as a veterinary technician or receptionist, if needed. Her husband is also an essential worker, and they are par ents to a 19-month-old son who is still in child care.

“I am also 22 weeks pregnant, which is the scariest part for me. I am not as con cerned with me getting sick, but with how it could affect the baby or my young son,” she said. “In my line of work, we have to come in very close contact with people when they hand off their pets. My pet hos pital is taking every precaution to stick to social distancing guidelines, but it’s impos sible to pass a pet over a six-foot space. We’re also touching owners’ leashes and harnesses, which can carry the viruses on them.”

Matrumalo wears a surgical mask and gloves, but her employer’s supply is dwin dling. Her own hours have increased, and she hears about the stress other employ ees are feeling daily. Most customers are grateful, while others take their stress out on her fellow employees, she said.

“We’re afraid to come to work every day, but this is what we signed up for in choos ing to work in the veterinary industry. We would like people to be patient with us as we constantly change our protocols to keep everyone safe and healthy,” she said. “…for me personally, it’s a constant battle of being afraid/ upset that I’m required to come to work, but I’m also grateful that I can still receive a paycheck.”

Nurses and health care workers aren’t the only moms working on the front lines. In New Hampshire, the essential services list includes hundreds of jobs in the food and agriculture, energy, utilities, transpor tation, and financial services sectors, to name a few.

Jennifer Buck of Merrimack works two part-time essential jobs — 20 hours a week at a bank, and per diem as a residential counselor, where she helps adults living with mental illness.

COURTESY PHOTO

JENNIFER BUCK, 41, of Merrimack, is a single mother to daughters Madelynne, 6, and Lylah, who is almost 4. Right now, she works two part-time essential jobs. She works 20 hours a week at a bank, which in cludes a mix of weekday shifts and Saturdays; and she has a per diem position as a residential counselor, where she helps adults with mental illness meet their treatment goals and assist with their daily living activities. Buck’s mother, a 65-year-old retired nurse, helps her care for Madelynne and Lylah while she’s at work.

Although Buck wears a fabric mask and gloves at both jobs, the threat of COVID-19 exposure still remains. She credits both of her employers for following proper social distancing recom mendations, sanitizing, and ensuring workers, customers, and patients are kept as safe as possible. The bank has provided its employees with an additional two weeks of paid time off and cash bonuses for employees who cannot work from home and she’s been assured that there won’t be layoffs as a result of the pandemic. Buck also has an opportunity to pick up extra shifts at the residential home because one of the other relief staff members can’t work due to family obligations.

As a mom who shares parenting time with her daughters’ father, Buck said her biggest worry is passing the virus on to other family members.

“My co-parent has voiced worries of me contracting the vi rus and the possibility of us both being sick at the same time, without anyone to care for the girls,” she said.

The stress of balancing two jobs in the COVID-19 environ ment particularly adds stress to single-parent families, Buck said.

“This has affected me emotionally because it takes addi tional mental energy to homeschool, and I already feel ‘spread thin’ as a single parent. My daughters miss school and seeing their friends, so they need more reassurance and attention from me than usual,” she said.

Videoconferencing calls via Zoom, worksheet packets, and activities geared to the kindergarten and preschool levels, as well as virtual dance and Hebrew lessons take the place of the girls’ normal classes and extracurricular activities.

Buck tries not to stress out about completing every activi ty each day and continues to be impressed by how organized her district has been and how attentive the teachers are to her daughters. She’s also thankful to be able to continue to work as it makes her feel less anxious while also keeping her feeling busy and helpful.

“I believe this unprecedented situation is hard on everyone, whether they are an essential worker or working from home. I feel it’s hardest on those who have been laid off or furloughed, since they have to worry about a change in income,” she said. “In my experience, for the most part, people seem gracious to those of us who need to work outside our homes and put our families at an increased risk.”

Krysten Godfrey Maddocks won three awards for writing from the Parenting Media Association in 2020.