58 minute read

Lessons from COVID vaccine rollout

Leading the First Phase of COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout

As expected, pharmacists have been on the front lines of the COVID-19 vaccination rollout, administering the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines to thousands of health care workers and other at-risk people nationwide. But it hasn’t been easy.

The early days have been marked by vaccine deliveries falling far short of projections, refrigeration breakdowns and other cold chain challenges, and in several states, vaccination gaps that have led officials to threaten hospitals with fines and reductions in future vaccine allotments. Yet through it all, pharmacy directors say they have been able to avoid breakdowns in vaccine delivery, thanks in part to careful planning and scheduling processes that had to be continually revised on the fly as guidance from federal and state agencies changed almost daily.

“The process around handling these vaccines, particularly [from] Pfizer, has to be like clockwork, and our members have practiced for that, even rehearsing the process of removing the Pfizer vaccine from the thermal shipper and placing it in the ultracold freezers,” said Anna Legreid Dopp, PharmD, the senior director of clinical guidelines and quality improvement for ASHP. “But we knew that there would be some bumps and some learning opportunities in the first weeks of vaccine distribution. For example, there were cases where some vaccine came in even colder than the allotted temperature range, which was something unexpected. We had been more concerned about warmer temperature excursions rather than colder, but this incident alerted us to the potential for lower temperature excursions as well.”

Legreid Dopp said ASHP has received multiple reports from member institutions about getting fewer allotments of vaccines than they were told to expect. “It’s likely a combination of raw material shortage impacting supply amounts, as well as the federal government holding back some doses,” she said. “We have also heard of some instances where vaccines have had to be replaced due to temperature variations in shipping.”

Delivery shortfalls may not be the only hindrance to more widespread vaccinations; some hospitals are struggling to administer even on-hand vaccines quickly. In New York, for example, state officials reported that the city’s public health hospitals had received about 38,000 doses, but as of Jan. 3, had vaccinated only 12,000 eligible employees. While state health officials attributed the gap to “logistical challenges,” Gov. Mario Cuomo said the culprit also was some health systems’ “lack of urgency” regarding COVID-19 vaccinations. He threatened to fine hospitals up to $100,000—and redirect future vaccines to other facilities—if they failed to close the gap quickly.

Legreid Dopp pushed back strongly against Cuomo’s criticisms. “Our hospitals are trailblazers. They have been giving 110% to this effort, but the capacity and resilience of our ... health care workforce is stretched thin,” she said. “They’ve been overwhelmed with treating critically ill COVID patients for almost a year now. They’ve been receiving information at the last minute about how many vaccines they will get and when.”

Legreid Dopp added that when it comes to the Moderna vaccine, some of the problems have stemmed from a communications loop that initially shut hospitals out, with McKesson serving as the centralized distributor to state departments of health. “We have some hospitals that have been able to form good, consistent, transparent communications with their departments of health, and in other states that has not happened,” she said. “Where there is that disconnect, hospitals are flying blind. We’ve been told that starting next week, hospitals will be included directly in that communications chain.” Jim Jorgenson, RPH, the CEO Jim Jorgenson, RPH, the CEO of pharmacy consultancy of pharmacy consultancy Visante, echoed Legreid Visante, echoed Legreid Dopp’s comments. “HosDopp’s comments. “Hospitals are stretched to the pitals are stretched to the Nth degree already, and Nth degree already, and you’re going to fine them you’re going to fine them for not giving the vaccine for not giving the vaccine fast enough when they’ve fast enough when they’ve been at ground zero?” he been at ground zero?” he said. “The federal governsaid. “The federal government has left it up to the ment has left it up to the states to organize this process. states to organize this process.

And the hospitals are at the And the hospitals are at the mercy of their states. The last mercy of their states. The last people in the world we should people in the world we should be blaming are hospitals.” be blaming are hospitals.”

As the following profiles show, As the following profiles show, health systems are navigating health systems are navigating these vaccinations challenges with these vaccinations challenges with a variety of operational strategies. a variety of operational strategies.

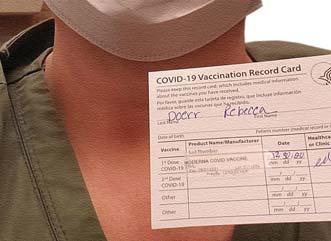

Rebecca Doerr, PharmD, a clinical pharmacist at Monument Health, in Rapid City, S.D., shows her vaccination card after receiving the vaccine as a front-line

health care worker.

South Dakota: Sanford Health

Sanford Health, the nation’s largest rural nonprofit health system, was among the first systems to receive doses of the Pfizer vaccine on Dec. 14, with 3,900 doses delivered to its hub in Sioux Falls, S.D., and 3,400 doses to its locations in Fargo and Bismarck, N.D. Frontline health care workers began receiving the vaccine the same day. “During that first week, 3,100 of the doses received at our hub in Sioux Falls were given to the top tier of front-line health care workers in the region,” said Jesse Breidenbach, PharmD, the senior director of pharmacy. “The remaining 800 doses were redistributed to other Sanford sites in the region and also to independent area hospitals, based on a plan we worked out with the state. The doses delivered to Bismarck and Fargo were all for our toptier, front-line health care workers.

“We have continued to receive allocations of vaccines from both Pfizer and Moderna,” Breidenbach added. “Some states are trying to focus the Moderna vaccine more in rural areas because of its easier handling and distribution.”

Sanford has eight ultracold freezers, but two are very small and can only service their own location. Six others, in Sioux Falls; Bismarck and Fargo; and Moorhead, Worthington and Bemidji, Minn., have enough capacity to continue to serve as hubs. “Our location in Moorhead is not providing vaccine supply to other hospitals in that west central region at present, but the state wanted us to keep that freezer available for subsequent tiers of front-line health care staff that may be more clinic based, as well as when we get to distribution for the public. It gives us more options.”

Breidenbach said Sanford had received fewer doses of vaccine during the later weeks of distribution, as the states began gearing up for their partnerships with pharmacies, including CVS Health and Walgreens, to vaccinate long-term care residents, which Sanford is not directly involved in. As of Dec. 28, the system had administered more than 11,000 vaccines. “Overall, it’s gone very well. The lack of a steady supply has caused us to have to tweak our vaccination clinics a little bit, because we’re always watching how many doses we have received and how many we have given, how many we think we’re getting, and then how many we know we’re getting once we get shipping confirmation. It’s always a moving target, and that’s been the biggest challenge.”

South Dakota: Monument Health

Serving western South Dakota and eastern Wyoming, the Monument Health system received its first shipment of the Pfizer vaccine on Dec. 14, the same day as its neighboring system, Sanford. “South Dakota is a very rural state, so the health department has relied on us, Sanford, and Avera Health, the other large system serving the state, to do a lot in the first couple of phases of vaccine distribution,” said Dana Darger, RPh, the director of pharmacy at Rapid City Hospital, part of the Monument system. “Most of the vaccine doses in South Dakota are being shipped through one of our three organizations and delivered out from there.”

Rapid City Hospital received a single flat of 975 doses of the Pfizer vaccine with that first shipment, which it stored in the only ultracold freezer it currently has—a bone freezer, used for preserving human bone for allografts in orthopedic surgery, housed in the surgical department—and finished administering that same week.

Darger said that on his facility’s first day of vaccinations, “we did our first five doses—one doctor and four nurses—for the media, which did a good job of covering the event for us. It felt like one of those monumental days, like the first step on the moon. If we can get the community to see that the doctors, nurses, pharmacists

Mayo Clinic medical staff members, in Rochester, N.Y., inspect a box of Pfizer/ BioNTech’s BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine as it arrives for initial storage and administration. The hospital received less than half of its initial projected doses and, like many other institutions, finds that it can get an additional 1-2 doses per vial from the Pfizer vaccine. (See page 1 story for more details.)

and others in the hospital are getting vaccinated at high rates and we believe this is safe, I hope that it will help the community accept it better.”

There were some logistical challenges, Darger acknowledged, such as scheduling vaccination appointments to coincide appropriately with thawing. “Ideally, you thaw the vaccine in the refrigerator for three hours,” he said. “You can do it for 30 minutes at room temperature, but if you do that you can’t put it back in the refrigerator. So, on our first days we had a couple of snafus where the vaccine wasn’t quite ready for people who were waiting for their appointments, but we didn’t want to do the room-temperature thaw because then you can’t refrigerate again. On the other hand, you don’t want people standing around waiting in line, because that violates social distancing rules. Scheduling people for these immunizations is logistically very different from how we would typically do a mass vaccination.”

With some practice, Rapid City Hospital reached a pace of approximately 10 to 12 people per vaccinator per hour, Darger said.

As of Dec. 28, Walgreens, CVS Health and smaller independent pharmacies in South Dakota had begun vaccinating long-term care residents and staff in the state, and once that phase of distribution is complete, Darger said Monument will again take a leading role in vaccinating high-risk individuals in the general population.

Connecticut: Yale New Haven Hospital

A central hub for the five-hospital Yale New Haven Health System, Yale New Haven Hospital received its first doses of the Pfizer vaccine on Dec. 15, began vaccinating the next day, and had administered all of the initial 2,000 doses to its front-line staff by Dec. 22. Like most other institutions, Yale New Haven made vaccination voluntary rather than mandatory at this point. “An employee will receive an emailed invitation to schedule their vaccine appointment, and then it is up to them whether they schedule it,” said Nilesh Amin, PharmD, the supervisor of pharmacy procurement and operations. That option also poses some difficulties when it comes to knowing how many daily vaccine doses to send to the hospitals. “If everyone signed up for all the available slots, then we could easily determine ahead of time how much to

send to each hospital; but since that is not the case, we are often waiting late into the day before we can determine what we are sending. At roughly 3 to 4 p.m., the schedule is closed for the following day, and that’s when we assess the numbers and send the appropriate amount of vaccine to each hospital.”

Minnesota: Mayo Clinic

Pharmacy leaders at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., initially worried about whether their ultracold freezers, which can store approximately 15,000 vials, would have the capacity to manage its role as a distribution hub for the Pfizer vaccine. They needn’t have worried, said Eric Tichy, PharmD, the vice chair of supply chain management. “We first received less than 3,000 doses at our big hospital in Rochester—basically, three personal pizza box–sized trays of vaccine with 195 vials in each tray,” Tichy said. “The original guidance was that we would get more than twice as much, but then they started dropping down their estimates of how much we were going to get.”

Mayo also experienced a slight delay in its first Pfizer vaccine shipments, expecting to receive doses on Dec. 14, but ultimately not receiving them until the 16th.. “Because of that, we opted to vaccinate through the weekend, not wanting to give up any days especially with the holiday coming up,” Tichy said. “But one good thing for us with having been on the later side of receiving these doses was that we were alerted to the extra dose in the vial. Some organizations wasted those extra doses at first, but now every level of government is saying to get at least a sixth and, if possible, a seventh dose. We’ll capture all of that, which is a bonus.”

University of Utah

The University of Utah, in Salt Lake City, has three ultracold freezers and a fourth on the way. Given those cold storage capabilities, the system is expected to primarily receive only the Pfizer vaccine. “In Utah, regulations require that we can only administer these vaccines at the site where they are delivered, and we do have the capacity to use the vaccine that requires special storage,” said Erin R. Fox, PharmD, an adjunct associate professor of pharmacotherapy. “The Moderna vaccine will be much more useful in the rural parts of the state, where our population is really spread out, so it should go to the hospitals in those locations.”

With COVID-19 cases surging in California and the Southwest, the University of Utah is facing critical demand. “We’re the only academic medical center for a long way, and we are getting calls from surrounding states, such as from Las Vegas, which would normally go to Los Angeles where they are inundated,” Fox said. “We have more patients than ever before and, thus, more health care workers who are front-line COVID caregivers, so our group of people who need the vaccine in the first phase keeps expanding. We’re just trying to get those doses into everybody’s arm as quickly as possible.”

The University of California, San Francisco

Farther north in the Bay Area, the University of California, San Francisco is a “multi-county entity” or MCE—the state Department of Health’s term for a vaccine hub—one of seven locations in the state that received syringe kits ahead of time to prepare for the vaccine rollout. The institution began vaccinating its front-line, highest-exposure health care workers on Dec. 16, reaching a pace of 500 per day by the end of that week and then increasing to 600 per day.

“We went completely through the weekend and were open 12.5 hours a day,” said Desi Kotis, PharmD, the chief pharmacy executive for UCSF Health. UCSF had finished that phase of immunizations by Dec. 23—a total of nearly 11,000

—Dana Darger, RPh doses. They were set to open additional vaccine clinics on Jan. 4, to immunize the remainder of its health care workers and expected “to be vaccinating 1,440 people per day in two separate clinics at that point,” she said.

Kotis noted that all UCSF COVID-19 vaccine clinics are run by pharmacists, with primary staffing from pharmacy student volunteers. “Pharmacists in California are providers, and while we have received interdisciplinary volunteers from the medicine, nursing and

see VACCINE ROLLOUT, page 12

Overdose Deaths Accelerating During Pandemic

COVID-19 has caused a lot of collateral damage to patients from decreased vaccinations to decreased cancer care. Its effects on the opioid epidemic, unfortunately, means a 38.4% increase in overdose deaths, according to the CDC.

The CDC looked at a 12-month span from June 2019 to May 2020 and found more than 81,000 overdose deaths—the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in a 12-month period.

Synthetic opioids—especially illicitly manufactured fentanyl—appear to be the primary driver, increasing overdose deaths to 38.4% in that period, according to the CDC.

During this period: • 37 of the 38 U.S. jurisdictions with available synthetic opioid data reported increases in synthetic opioidinvolved overdose deaths; • 18 of these jurisdictions reported increases greater than 50%; and • 10 Western states reported over a 98% increase in synthetic opioidinvolved deaths.

Although overdose deaths already were increasing in the months preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, the agency admitted, the latest numbers suggest an acceleration of overdose deaths during the pandemic. “The disruption to daily life due to the COVID-19 pandemic has hit those with substance use disorder hard,” CDC Director Robert Redfield, MD, said in a statement.

Steven J. Martin, PharmD, the dean and a professor at Ohio Northern University Rudolph H. Raabe College of Pharmacy, in Ada, said his group has been watching this unfold in his rural area all year. “Unfortunately, opioid-related deaths have reversed the trend we saw in

VACCINE ROLLOUT

continued from page 11 dental schools, the vaccinators are primarily our pharmacy students. Students with pharmacist oversight are drawing up every dose, reconstituting, labeling, ensuring the needles are attached, logging the barcode scans on every syringe, and ensuring the utmost safe environment. It’s really an extraordinary effort.”

In Wisconsin, a Moving Target

Froedtert & the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) health network received its first 2,925 doses of the and began vaccinating the next day. “Things have been evolving almost hourly in Wisconsin with the initial vaccine 2018 and 2019, and COVID-19 is largely responsible,” Martin told Pharmacy Practice News.

Although much of the escalation is due to illegal opioid procurement, there are several actions that health care workers, particularly pharmacists, can take, said Martin, who also sits on the Pharmacy Practice News editorial advisory board.

“Pharmacists must check state PDMP [prescription drug monitoring program] databases to identify opioid misuse patterns; educate every patient who receives an opioid prescription about the management of pain, risk of addiction and use of naloxone for those at higher risk; and partner with prescribers to reduce coprescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines and prescribing opioids at more than 50 MME [morphine milligram equivalents] per day,” Martin said.

“All health care professionals should provide basic screening for persons suffering from drug use disorders, and provide direction to services in their community that can address addiction,” he said, and “this is particularly important in the rural setting where access to the health care system is limited, and treatment programs may not be available without significant travel.”

Not Just Opioids

Overdose deaths involving cocaine also increased by 26.5%, according to the CDC. Based on earlier research, these deaths are likely linked to combined use or contamination of cocaine with illicitly manufactured fentanyl or heroin. Overdose deaths involving psychostimulants, rollout,” said Philip Brummond, PharmD, the chief pharmacy officer for the Froedtert & MCW health network. Noting that “there was a phased approach” across the state, he said, “we received our initial shipment later than expected.”

MCW received another shipment of 4,300 doses by the end of December, and at press time was anticipating an additional 9,000 doses of vaccine—some combination of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines—the first week of January.

Brummond also stressed the logistical challenges of thawing time and appointment scheduling. “We’re giving 60 vaccines per hour in one of our clinics, so it’s taken us some time to calculate planning for thawing and reconstitution,” he said. “The first few days were a challenge for us to make sure every single dose we drew up was used in the appropriate ‘Unfortunately, opioid-related deaths have reversed the trend we saw in 2018 and 2019, and COVID-19 is largely responsible.’

—Steven J. Martin, PharmD

such as methamphetamine, increased by 34.8%. The number of deaths involving psychostimulants now exceeds the number of cocaine-involved deaths, the agency said.

“The increase in overdose deaths is concerning.” said Deb Houry, MD, MPH, the director of CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. “CDC’s Injury Center continues to help and support communities responding to the evolving overdose crisis. Our priority is to do everything we can to equip people on the ground to save lives in their communities.”

The CDC recommended these actions: • Expand distribution of naloxone and overdose prevention education. • Expand awareness about and access to and the availability of treatment for substance use disorders. • Intervene early with individuals at the highest risk for overdose. administration timeframe.”

Brummond said he anticipates “additional logistical issues” as the vaccination efforts pick up steam, including “scheduling patients for second doses while we are also scheduling first doses, all while preparing to do community immunizations within our clinics. I’m very encouraged [that] we have been able to coordinate getting the vaccine administered at the pace we have. It speaks well to our system’s ability to provide vaccines to the community in an expedited fashion.”

ASHP’s Legreid Dopp expressed relief at the Jan. 6 announcement from Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar that community-based pharmacy immunizations would be rolled out sooner than expected. “We applaud that, but we need • Improve detection of overdose outbreaks to facilitate more effective response.

Education should be a priority, Martin added. Pharmacists can provide education in their communities about the dangers of opioid misuse, and help to reduce the stigma of addiction as a criminal activity. He said it is important for everyone, including health care workers, to recognize it as a medical concern.

“As we continue the fight to end this pandemic, it’s important to not lose sight of different groups being affected in other ways. We need to take care of people suffering from unintended consequences,” Redfield said.

For more coverage of OUD, see page 4.

—Marie Rosenthal

The sources reported no relevant

Pfizer vaccine around 5 p.m. on Dec. 17,

Next Steps

fi nancial disclosures. to put the full force of the public health system behind this effort now,” Legreid Dopp said. “We’ve been advocating for a long time that this will take mobilization of traditional and non-traditional immunizers and immunizing locations, and now it’s time to move beyond the walls of hospitals and health systems. That includes community pharmacies, ambulatory health clinics, even schools and faith-based institutions. Hospitals and health systems have been carrying the baton for this first leg of the relay, but now it’s time to bring in the rest of the relay team too. A lot more vaccines are coming down the pipeline and now is the time to get this right.” —Gina Shaw

Room for Growth in PGx-Guided Transplants

Drug treatment based on pharmacogenomics, already a significant factor in oncology, psychiatry, pain management and anticoagulation therapy, is poised to play an important role in transplant medicine, a leading pharmacogenomics expert noted during the American College of Clinical Pharmacy 2020 virtual annual meeting.

The number of transplant patients who could benefit from personalized medicine is huge: one recent study found that 100% of nearly 900 organ transplant patients had at least one actionable pharmacogenomic phenotype that could explain suboptimal therapeutic responses to immune-suppressing agents (J Clin Pharm Ther 2020 Jul 14. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13223).

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) has released guidelines involving several drugs that would have some application on in organ transplantation, including tacroolimus, voriconazole, clopidogrel, selecctive serotonin reuptake inhibitors, 5-HT3T agonists, thiopurines and proton pump mp inhibitors. Another key source is the he FDA, which regularly updates its “Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labeling” (bit.ly/3hh5qnx).

“Over 100 of those drugs are relevant to transplantation,” said Pamala Jacobson,

We help you achieve extraordinary results in all areas of health system pharmacy

Strategic Planning & Implementation

We collaborate with you to deliver innovative solutions that will elevate your organization to peak performance levels.

Compliance that Improves Care

Our team of compliance experts will improve confi dence, enhance care and ensure patient, worker and community safety.

Financial Results

Making the most of opportunities to manage costs and increase revenue is core to our consulting. We help you improve fi nancial performance across your organization.

Visante consultants bring you expertise in all areas of hospital and health system pharmacy:

• Comprehensive Strategic Assessments • 340B Program Solutions • Specialty Pharmacy Programs • Revenue Cycle and Drug Reimbursement

Strategies • Supply Chain Strategies • Drug Diversion Programs • Drug Compounding Excellence

Connect with Visante today to learn how we can help you reach your goals. Visit us at visanteinc.com, or call 866-388-7583.

PharmD, a distinguished professor in the Department of Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology and the director of the Institute of Personalized Medicine at the University of Minnesota College of Pharmacy, in Minneapolis. “So, although the FDA is not providing recommendations here, it is providing data suggesting that these are legitimate drug-gene pairs that could be used in clinical practice.”

Jacobson pointed to a study involving 853 kidney transplant recipients (J Clin Pharm Ther 2020 Jul 14. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13223). “Each transplant recipient had at least one actionable CPIC pharmacogenomic phenotype from 13 pharmacogenes,” she said. Moreover, “58% of the study participants had three or four [phenotypes], and over 20% had five or more.”

Jacobson cited tacrolimus as one example of a drug with significant pharmacogenomics potential in transplantation. “We know that transplant recipients with low tacrolimus troughs are more likely to develop donor-specific antibodies, which can lead to other immune problems, in particular rejection,” she said. “The threshold is 8 ng/mL, and we want everybody above that if at all possible.”

Jacobson pointed to cytochrome enzyme CYP3A5 polymorphisms as particularly relevant to tacrolimus therapy, contributing to clinically significant differences in tacrolimus bioavailability between individual patients. Up to nine different alleles have been identified in CYP3A5, with *1 (normal function) and *3 (loss of function) being most common and best studied (Pharmgenomics Pers Med 2018;11:23-33).

Studies have identified differences in tacrolimus metabolism between white and Black transplant recipients based on CYP3A5 variants, Jacobson added. “For example, a genome-wide association study of tacrolimus troughs in African American transplant recipients found that there are three genetic variants that are extremely important: CYP3A5 *3, CYP3A5 *6 and CYP3A5 *7. In the African American population, when you combine clinical variables with these loss-of-function variants, you can explain more than 54% of the variability in trough concentrations” (Am J Transplant 2016;16[2]:574-582).

Earlier trials of genotype-directed dosing of tacrolimus have had mixed results, she said. A French study found that patients who received genotype-directed dosing of the drug were more likely to

Of 853 kidney transplant recipients:

100% had at least one actionable CPIC pharmacogenomic phenotype 58% had 3-4 20%+ had 5 or more

Source: J Clin Pharm Ther 2020 Jul 14. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13223 [Epub ahead of print]) CPIC, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium

be in the appropriate therapeutic range at days 3 and 10 after transplant, but no difference in rejection and graft outcome was found at five-year follow-up (Pharmacol Ther 2010;87[6]:721-726; Am J Transplant 2016;16[9]:2670-2685). A Dutch trial found no differences in troughs or graft outcomes, but also no differences in adverse events, so Jacobson noted that it suggested safety of this dosing approach (Am J Transplant 2016;16[9]:2670-2685). However, the trials had limitations, Jacobson said. “For example, they studied only a single polymorphism, directing dosing just at allele *3, and we now know many others are important.”

The transplant field represents an early success and “a huge opportunity for pharmacogenomics,” said Henry “Mark” Dunnenberger, PharmD, the director of pharmacogenomics at NorthShore University HealthSystem, in Manhasset, N.Y., with tacrolimus dosing at the forefront. “Tacrolimus dosing is complicated and has a narrow therapeutic window,” he said. “We had long known about dosing variability from the package insert, which states that the data in kidney transplant patients indicate that Black patients required a higher dose to attain comparable trough concentrations to [whites]. The original clinical studies weren’t looking for genetic variation but they saw the trend, and now we have the genetic reason behind it.”

Another agent commonly used for transplant patients, voriconazole, is primarily dependent on the CYP2C19 genetic pathway, Jacobson noted. She cited a recent study of genotype-directed dosing in patients receiving allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplants (J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2020;107[3]:571-579). “Poor metabolizers, intermediate metabolizers and normal metabolizers initiated voriconazole therapy at a standard dose of 200 mg twice daily, while rapid and ultrarapid metabolizers were started at 300 mg twice daily,” Jacobson said. “Only about 30% of the study population were in the subtherapeutic range for trough concentrations, compared with 50% of historical controls. The difference was particularly dramatic in the rapid and ultrarapid metabolizers: Only about 16% of them were subtherapeutic, compared with 70% of historical controls.”

The authors also conducted a cost analysis. “One fungal infection costs about $50,000 to treat in these patients,” Jacobson said. “They found that doing genetic testing in all patients for dosing of voriconazole would save an estimated $4,700 per patient compared with historical controls. This suggests that broad pharmacogenetic testing in an entire transplant group could be cost-effective.”

Jacobson stressed the importance of combining pharmacogenomic information with clinical variables, such as age and drug–drug interactions, in dosing models. In going so, “you can explain more than half of the variability in tacrolimus trough concentration,” she said (Am J Transplant 2016;16[2]:574-582).

Jacobson and her team developed a model that combined these factors, which resulted in the first reported African American–specific, genotype-guided tacrolimus dosing model (Pharmacogenomics J 2017;1:61-68). “To determine the dose, the model includes the genotypes, whether the patient is receiving steroids and/or antivirals, and their age,” she said, adding that the model is for immediaterelease tacrolimus and that a new model will be needed for the once-daily product. “This approach highlights where we need to go with pharmacogenomics writ large as well as in transplant specifically,” Dunnenberger said. “Genomics don’t affect patients in a silo. You have to think about clinical and genetic factors together to identify the right medication and the right dose for each patient.” The goal, he added, is to get into “the Goldilocks zone,” where “you have just the right amount of data that can be turned into action, without overburdening the system.” —Gina Shaw

The sources reported no relevant fi nancial disclosures.

Like What You Read in Pharmacy Practice News?

Be sure to say you read 4 out of 4

An independent readership survey may be emailed to you soon. If you like how we cover the news in PPN, say you read 4 out of 4 issues cover to cover!

The wholesaler and the health system:

A Powerful COVID-19 Partnership

Add the University of Chicago Medicine (UCM) health system to the list of facilities that are sharing their successes in meeting patients’ needs during even the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Rapid intervention emerged as one of the most important tools for ensuring optimal clinical outcomes, Kevin Colgan, MA, FASHP, UCM’s vice president and chief pharmacy officer, told Pharmacy Practice News. The 1,296-bed health system estimated that nearly 80% of its relatively early COVID-19 admissions in 2020 were at high risk for a severe disease course.

Senior leaders at UCM had prepared for this “very sick population” with weekly command meetings starting in January that became daily in March. Part of that planning, he noted, focused on the importance of maintaining adequate stocks of medications. On Jan. 31, 2020, he noted, “I raised concerns that much of the APIs [active pharmaceutical ingredients] were made far away in China with long shipping times, and massive drug shortages were emerging worldwide. I requested additional space to store drugs and got permission to stockpile five months’ worth,” Colgan said. “Within one week, we identified 180 critical drugs for all patients—such as for surgeries, cancer and clinical trials we run—not just COVID-19.”

Colgan recognized early that routine wholesaler allocations to hospitals based on historical medication usage would be insufficient in the pandemic. “You have to allocate based on the number of COVID-19 patients. McKesson [UCM’s wholesaler] had to throw out old ways of doing things” and channel more inventory to hospitals as hot spots shifted to Detroit, Chicago, New Orleans, New York City and elsewhere, he said.

Preferred Therapies Maintained

Ample inventory enabled UCM physicians to continue prescribing their preferred drugs for COVID-19 patients, with one exception, Colgan said: For five weeks, UCM needed to

Innovation in Secure Drug Delivery

Simple, Innovative Solutions to Enhance Drug Security

Prep-Lock™Tamper Evident Caps for IV Syringes are an active deterrent to potential tampering or misuse. They help ensure syringe integrity is maintained from the time it leaves the sterile hood until it is administered by an authorized clinician. IMI has been creating American-made products for the compounding pharmacist for over half a century. Our quality, reliability and exceptional customer care have made Prep-Lock Tamper Evident Caps an industry standard for guarding IV Syringes. switch to rocuronium as an infused neuromuscular blocker when cisatracurium wasn’t available. McKesson told Pharmacy Practice News that orders for cisatracurium increased by about 500% nationwide between February and March 2020. “We saw demand for many medications far outpace what historical ordering patterns suggested,” said Dave Ehlert, PharmD, MBA, area vice president at McKesson Health Systems.

“We were successful treating patients because we had access to drugs,” said Colgan, adding that McKesson “was instrumental in getting our orders filled and bringing us information on what manufacturers were doing. We also had a newer hospital with more negative-pressure rooms and an emergency department retooled” for the influx of patients.

The health system collaborated with McKesson’s RxO division for domestic and global outreach to sustain sourcing. Teams at UCM also searched daily for new peer-reviewed literature on COVID-19, prepared treatment algorithms and adapted as needed. As soon as UCM learned of promising agents based on the early experiences of other centers managing the disease, including those in Wuhan, China, where the outbreak began, the health system moved quickly to obtain the medications.

Colgan cited, as examples, lopinavirritonavir (Kaletra, AbbVie) and tocilizumab (Actemra, Genentech), both of which gained some early traction as COVID-19 therapies. “We wanted enough [of these medications] to treat at least 400 to 500 severely ill COVID patients, and we weren’t the only ones,” he said. (Many early COVID-19 treatments have not held up to scrutiny. In the case of lopinavir-ritonavir, a study found that in hospitalized adult patients with severe COVID-19, no benefit was observed with the combination treatment beyond standard care [N Engl J Med 2020;382(19):1787-1799]).

Mixing It Up

Among urgent efforts to keep UCM ahead of the pandemic, Colgan said McKesson redistributed medications from other states less affected by the virus, assisted with drug supply for a shared canister program of albuterol metered-dose inhalers practically overnight, and put him in direct contact with a manufacturer of tocilizumab, which drop-shipped his orders to McKesson. Because tocilizumab is a specialty pharmaceutical for rheumatoid arthritis patients, it took more resourcefulness to secure a supply, he explained.

The health system largely secured what it needed because Colgan provided UCM treatment algorithm information and patient volume data as they occurred to McKesson. The data detailed UCM’s fluctuating counts of confirmed and suspected COVID-19 patients, patients in ICU settings, and patients who were mechanically ventilated. UCM sent the data to McKesson account executive Kristina Cole, who shared it with McKesson’s supply chain and RxO teams to accurately forecast and fulfill UCM’s upcoming medication needs. Cole also relayed back to Colgan the continuously renewed supply chain insights disseminated by McKesson RxO’s newly formed Critical Care Drug Task Force.

McKesson formed the task force—a working group of 20 professionals across McKesson, including data scientists, procurement, distribution and regulatory experts, and pharmacists experienced in health-system pharmacy operations and optimization—to support hospital pharmacies as they identify drug therapies needed to treat COVID-19 patients.

The task force also forecasted demand based on dosing requirements and discussions of alternative therapies based on reference literature, according to Barbara Giacomelli, PharmD, MBA, McKesson RxO’s VPAdvisory, Pharmaceutical Solutions and Services. Task force members continue to track 222 critical care medications on its master list—not yet including investigational vaccines— and color-code each one red, yellow or green by the degree of supply constraint and critical need, she said.

The task force has broad access across McKesson to bring intelligence from many disciplines to health-system customers. Its members obtain and interpret data about finished drug supplies at manufacturers and in the pipeline, as well as location and availability timing of preferred and alternative therapies;

they then filter the information to sales leadership and local account executive teams, who in turn share it with hospital customers, such as UCM. They mine the data using multiple McKesson tools—Utilization Analytics, 340B Purchasing Dashboard, and Patient Assistance Recovery Software and Connect Reporting—to help optimize medication flow, mitigate spend and optimize revenue for hospitals.

The task force also interviews hospital customers about their dosing, and reviews national and international clinical recommendations and treatment guidelines, and newer protocols being investigated, Ehlert added.

“We never knew which way the pandemic curve would go, so I consistently ordered 25% more than I thought I’d need, and I was never disappointed,” Colgan said. “[Yet] if I had extra medications and another hospital needed some, I’d share.”

Amid the COVID-19 surge, Colgan said he recognized the importance of collaborating with McKesson not only to protect UCM’s ability to care for patients, but also to avoid putting other hospitals in a bind by cornering scarce resources. “I knew if I stockpiled a fivemonth supply of mission-critical drugs for UCM, it would cause disruption to McKesson,” so he called to alert them first before increasing his orders.

Specialty Pharmacy Responds

For specialty pharmacy at UCM, the COVID-19 challenge was mostly about keeping in contact with patients who stopped their clinic and ambulatory visits to stay at home, and still needed their medications.

The health system stepped up its telehealth and mail-order initiatives to protect patient health and add convenience. As visit counts fell, “telehealth grew overnight [to the point] we’re now at 80% pre-COVID volume of business,” Colgan said. “Our clinic visits are now back to about 46% in person, and it should maintain there for a while.”

Colgan said he expected UCM’s telehealth and mail-order shipment expansions to help its specialty pharmacy patient count grow from 1,750 to 2,000 per month by the end of 2020. “We asked specialty patients we mail to monthly if they had other pharmaceuticals they didn’t want to go to the drugstore for. When they said yes, we filled their maintenance medication prescriptions and mailed it to them,” he explained. “COVID was much less a factor for us in terms of specialty drug supply than was being reported by others.”

Still, “there are several specialty medications being investigated for COVID-19,” such as anakinra (Kineret, Sobi) and tocilizumab, noted Dave Ehlert, PharmD, MBA, FASHP, area vice president, McKesson Health Systems.

In the case of tocilizumab, the most recent data are not promising. In December, a study concluded that the interleukin-6 receptor blocker was not effective for preventing intubation or death in moderately ill hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (N Engl J Med

The sources reported no relevant fi nancial disclosures other than their stated employment.

Only on the Web: 6 Best Practices to Manage COVID-19–Related Drug Shortages

See expanded article at pharmacypracticenews.com.

2020;383:2333-2344). —Al Heller

continued from page 1

At NYC Hospital, Medication Bundling Tops the List

Two strategies—medication “bundling” and savvy tweaks to automated dispensing cabinets (ADCs)— helped Jawad Saleh, PharmD, the clinical manager of pharmacy services at New York City’s Hospital for Special Surgery, navigate the COVID-19 crisis at his hospital.

The ADC changes were particularly helpful in transforming hospital areas into ICUs and identifying key workflow modifications during COVID-19, Saleh said at the ASHP 2020 Midyear Clinical Meeting and Exhibition. When hospitals adapt other spaces, such as operating rooms (ORs) or PACUs, into COVID-19 ICUs, he noted, placement of ADCs and pumps is a key consideration. “These need to be strategically placed in clean areas, with the goal of decreasing pharmacy staff exposure and decreasing medication contamination,” Saleh said. “Speak to your engineering and network teams to place adequate electrical outlets. Remember that ADCs moved to a different unit must be renamed temporarily to prevent staff confusion.”

Two refrigerators per unit would be ideal, he noted, with one allotted to patient-specific medications and the other containing bins for the most common noncontrolled infusions. He also recommended temporarily increasing medication par levels to decrease the frequency of restocking and reducing traffic to the ADCs, while also removing slow-moving medications to help with capacity.

Placing pumps outside of COVID-19 ICUs has been a strategy used to preserve personal protective equipment (PPE) and reduce the frequency of exposure for nurses, as previously reported in Pharmacy Practice News (bit. ly/3os0K1s). But it’s not a universal fit, Saleh said. “It’s best for isolated patient rooms, preferably single-patient [rooms], and not practical for open-suite units and OR rooms, which are too big.”

Saleh added that pumps outside of rooms work best with central lines, and arterial line blood pressure monitoring is preferred. “Small bore extension tubing has less volume in the tubing between the infusion and patient, so it reaches the patient more quickly,” he said. “Additionally, use caution with very high infusion rates, because resistance to the flow may occur. It’s also important to label lines and tubing at the pump and end of extension tubing, to help nurses identify medications at site of connection to patients.”

Some medications are preferred with extension tubing, including vasopressors (excluding vasopressin), inotropes, sedatives and analgesics, Saleh noted. The following are discouraged with extension tubing: amiodarone; vasopressin; chemotherapy; electrolyte replacements (to avoid accidental bolus); insulin, which requires blood glucose monitoring every one to two hours; heparin, because changes are only made every six hours; drugs requiring large bolus volumes for proper flushing; and maintenance fluids. Saleh added that increased drug waste is common with extension tubing.

During a surge, staff may step into roles they are not accustomed to, so regular education is essential. “For example, inpatient nurses utilize Pyxis [BD] machines, and operating room nurses who aren’t familiar with Pyxis must be trained,” he said. “CRNAs [certified registered nurse anesthetists] don’t have access to Pyxis, because they usually use Omnicell when in the OR. Get a staff list from the manager of that specific unit and grant access immediately while providing in-service trainings regularly.”

Based on the acuity of COVID-19 patients, the Pyxis override list will likely need to be expanded, he added, increasing the amount of medications that can be overridden in an emergency without having an order in place. “If access and training are done properly, it will alleviate a lot of pressure from both pharmacy and the ICU and prevent delays in patient care.”

Medication Bundling

Medication bundling was another key strategy for Saleh and his colleagues during the pandemic. The practice, which they continue to employ, involves consolidating medication times together to help limit how often nurses need to enter and exit patient rooms. Done correctly, medication bundling “helps minimize health care professionals’ exposure to the virus, limit contamination and conserve PPE,” Saleh said. “At our hospital, for example, our medication times were 10 a.m. and 10 p.m. You can piggyback your scheduling based on time-sensitive medications that must be given priority, such as antibiotic or drugs for Parkinson’s disease. So if there’s a Parkinson’s medication that must be given at 7 a.m., then you’d stack everything at 7 a.m. and 7 p.m.

And when you have And when you have known drug–drug interacknown drug–drug interactions, separate those medications, separate those medications based on the chosen time slots.” tions based on the chosen time slots ”

Saleh offered guidance on bundling medication regimens for several specific indications:

Bowel Regimens

Polyethylene glycol and senna-based laxatives are preferred to options that must be given more frequently, such as lactulose. For stress ulcer prophylaxis, he said, patients with a creatinine clearance greater than 50 mL/min should be given pantoprazole-esomeprazole 40 mg orally or by nasogastric tube daily. Patients who are on non-oral regimens should receive a slow IV push to reduce fluid intake and maintain stock in the ADC. For patients with a creatinine clearance less than 50 mL/min, he recommended famotidine 20 mg daily, unless there are other indications for a proton pump inhibitor.

Glycemic Control

Minimizing fingersticks by needles reduces another source of potential exposure, Saleh said, adding that “arterial blood is best for glucose measurements in this setting.” If there is no arterial line, “use Novastat [Taconova] machines, which are good for accounting for variances. You can also employ patients’ own home-based intermittent glucose monitoring and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems. There’s a huge value for nonintubated patients to be able to scan themselves if they have the FreeStyle Libre [Abbott; CGM system] and the reader in place.”

These systems have not been approved by the FDA for use in hospital settings, but the agency has temporarily waived this limitation during the pandemic to limit fingerstick blood glucose testing for monitoring and insulin administration. An agency statement released on July 9 stated: “The FDA recognizes that home-use “T T“ he h FD blood glucose meters may be an option bl b o ood gl to provide relief and support to health to prov vi care professionals in hospital and longca ac re pr ro term care facility settings seeking to ter rm ca reduce interactions between patients re ed duce ec and health care providers, thereby liman nd h he ea iting exposure to COVID-19, and conit iti in ng e ex serving PPE, whenever possible.” se er rvin ng

For glycemic management, Saleh F For g again recommended longer-acting ag gain n products, such as insulin glargine, once pr rp oduc ct daily, plus shorter-acting products such da daily, pl as insulin regular human (Humulin R, as a insu ul Eli Lilly, or Novolin R, Novo NordEli Li illy isk) or insulin lispro (Humalog, Eli isk k) or Lilly), depending on supply. “Once Li L lly), the patient’s blood glucose is stable, the pat you may consider the use of Humalog yo oy u m may 75/25, with total daily insulin require75/2 / 5, , w ments split in two, twice daily,” he ments s said. “Consider holding these products said. “C when tube feeds are held, such as in when tu prone positioning; when tube feeding prone p is stopped for 18 hours; or extubation, is stopp when it is stopped for six hours.”

Opportunistic Infection Prophylaxis

Before recommending infection prophylaxis, Saleh noted, pharmacists should confer with the hospital’s infectious disease service about regimens that minimize exposure. “In the ICU, we recommend daily fluconazole, which can be crushed, for antifungal prophylaxis rather than clotrimazole troches or topical nystatin. For antiviral prophylaxis, [use] once-daily valacyclovir over acyclovir, which has much more frequent dosing.”

Cardiovascular Regimens

“In general, we recommend longacting medications—XL, XR, SR—if the patient is hemodynamically stable and able to swallow,” Saleh said.

He recommended that hospitals consider increased jurisdiction for pharmacists to be allowed to make some of these changes automatically in light of the pandemic. “You are protecting everyone on your clinical staff—medical, nursing and pharmacy—by bundling and minimizing the frequency of people going into and out of the rooms of patients with COVID-19.” Continued on facing page

3 Strategies for Preserving Quality And Safe Practices in Critical Care

The COVID-19 pandemic has stretched ICU resources at an unprecedented fashion. A shortage of certain drugs and PPE, the inclusion of some non–ICU-trained physicians to manage patients, and families barred from live visits can insert barriers to best practices in ICU patient care honed over time.

Two critical care pharmacists offered strategies for overcoming these challenges during a session at the ASHP annual meeting. 1. Watch out for delirium. Many hospitalized patients with COVID-19 will develop the condition, noted Janelle Poyant, PharmD, BCPS, BCCCP, a critical care clinical pharmacy specialist at Tufts Medical Center, in Boston. Encephalitis and encephalopathy with acute psychosis have been well documented in the context of influenza, and some data suggest that this may result as a consequence of the intense systemic and brain inflammatory responses (Eur Geriatr Med 2020;11[5]:857-862).

In patients with COVID-19, delirium may result from direct central nervous system invasion of the virus, or factors such as prolonged mechanical ventilation time, polypharmacy and experimental treatments. This is coupled with environmental factors that include extreme isolation and the inability to freely ambulate, she said.

2. Rely on sedation bundles, when

possible. There is a need to implement sedation protocols to limit rates of delirium and other complications of ICU stays, Poyant said. The Society of Critical Care Medicine’s A-F Bundle (www.sccm.org/ICULiberation/ABCDEF-Bundles) of elements is one way to align and coordinate care that includes a range of activities, from assessing pain to choosing the right sedation and promoting early mobility. The bundle strives to optimize pain management, avoid deep sedation, d deep sedatio on, reduce delirium and shorten the duraho orten the du ura ation of mechanical ventilation, among nt tilation n, am amon ng g other goals.

Still, there are many COVID-19–relatC COVID-19 1 –rela ated issues and barriers that may preclude ha at may y pr p eclu l d de e the use of these practices, “particularly e es, “particula ar rl ly y at hospitals experiencing patient surges” g g patien nt su us rges es” during COVID-19, said Brianne Ritchie, B Brianne e Ri iR t tch hi ie, e PharmD, BCCCP, BCPS, a critical care S, , a crit tica al ca c re er clinical pharmacist with CHI Health th CHI I Healt th h Lakeside, in Omaha, Ne N Neb. Increased b. Incre eased d patient volumes with overflowing ICUs verflow wing g ICU CUs and hospitals, shortages of important e es of im mpo ortan ant t medications and equipment, policies p pment, , polici ie es s on masking, and restrictions on visiic ctions on n vis sitors all can negatively affect the ways a affect the h way a s s in which ICU staff assess and manage e ess and d m ma ana n ge ge pain, agitation and delirium, and optimize mobility and family engagement, Ritchie said. The need to adopt social distancing and increased workload demands have further pushed multidisciplinary care and collaboration away from ideals.

“Because the A-F Bundle is so effective at optimizing ICU liberation, we as clinicians must recognize these challenges exist and apply strategies to overcome them in an effort to mitigate the negative consequences of ICU care, and subsequent post-discharge morbidity as best possible,” she said. 3. Keep an eye on workflow. Applying the bundle elements to reduce mechanical ventilation duration and decrease ICU length of stay seems like a perfect match made everything go smoother, and now that we are facing a second wave it’s nice that everything is already built out on the ground,” Clark said.

URCM has developed another COVID-19 coping strategy: an inventory optimization tool that demonstrated its value during a rapid build-up to meet an anticipated surge in COVID-19 patients.

“We had to go quickly from about 900 beds to 700 additional beds,” said David Webster, RPh, MSBA, the director of acute care operations at the New York hospital. The hospital’s cafeteria, gymnasium and some underused ambulatory clinics were among the areas designated to fill the expected demand. Fortunately, the number of cases never tested the increased capacity.

Still, Webster noted, with cases rising, the challenge was how to increase and repurpose automated dispensing for the pandemic, Ritchie said. However, this requires substantial clinician resources and time that many institutions struggled to provide even pre-pandemic. There have been a number of changes in ICU care as hospitals prepared for and managed surges, as well as shifts in daily interprofessional team rounding practices, Ritchie noted. In such conditions, patient care decisions often revert to isolated conversations outside the robust input of multidisciplinary colleagues that has become best practice, she warned.

“Maintaining the interprofessional team may require novel approaches,” Ritchie said, “such as virtual participation from colleagues and other areas of the hospital, as well as family members

Strong Memorial’s Approach To Maintaining Stronger ICUs

At Strong Memorial Hospital, part 2020 virtual annual meeting. They also eting. They y also o of the University of Rochester initiated enhanced VTE prophylaxis TE proph hylax xis s Medical Center, clinical pharmacists dosing and developed initiatives to prewere concerned about non–ICU- serve PPE and minimize nursing expotrained physicians having to take care sure, among other tasks. This included of critically ill COVID-19 patients dur- bundling the timing of medications to ing a surge in cases. So they crafted a prevent nurses from entering patient strategy aimed at ensuring that such rooms as often, and using continuous patients are treated optimally. infusions from outside the rooms.

“We wanted to create a model that Then, as the hospital accumulated its really would help out the physician own population of COVID-19 patients, group and entire interdisciplinary critical care pharmacists rotated coverteam by creating guidelines and build- ing the COVID-19 ICUs and reviewing ing order sets in the medical chart patient charts daily to optimize pharto make things foolproof,” said Jenna macotherapy and discuss recommenClark, PharmD, BCCCP, a clinical phar- dations with the covering providers. macy specialist for the hospital’s medi- Among 137 COVID-19 patients hospical ICU, in Rochester, N.Y. talized between March 30 and May 15,

Clark and her colleagues created an the pharmacists enacted 1,322 interadmission order set in the hospital’s ventions, such as adjusting medicaelectronic health record, critical drug tion doses, altering pain and sedation shortage guidance documents for IV regimens or recommending changes analgesics and sedatives, and a clini- in bowel regimens. Pharmacists also cal practice guideline for COVID-19 adjusted guidance documents, as necpharmacotherapy, she noted during essary, based on medication shortages a COVID-19 session at the American or updated treatment guidelines. College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) “It was a lot of work but it definitely

A Boon During COVID-19 Surge

at home.” cabinets to meet the needs of this new critical patient population.

“Early on,” he said, “we decided to prebuild some machines in anticipation of this surge.” Some were pulled back and new ones ordered. In a conference room, he added, an ICU and a non-ICU setup sat ready to deploy, connected to the network and prefilled with medications. “We had to use this several times as we opened areas and moved patients into them.

“Very valuable in that process was knowing what our data told us were the typical medications and par levels we needed for the type of patients moving into those areas,” Webster added. “The advantage of having this tool live was that we could look at what we needed to load into those machines. We used it pretty extensively as we saw patient populations shifting pretty quickly.”

continued from previous page

Cooper University: 4 Steps to Tame VTE

Mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 face a significantly increased risk for developing venous thromboembolism (VTE) compared with non-critically ill patients with the disease, according to Lauren A. Igneri, PharmD, a critical care clinical pharmacy specialist with Cooper University Healthcare, in Camden, N.J. amden, N.J.

“Coagulopathy has been observed n observed in 15% to 39% of COVID-19 patients 19 patients requiring mechanical ventilation,” entilation,” Igneri said during the ASHP annuSHP annual meeting, citing one recent study cent study (Blood 2020;136:489-500). “Early ). “Early observations suggested that elevated at elevated D-dimer levels were associated with an ted with an increased risk of mortality, and this and this suspicion was further heightened ghtened with autopsy results that found und in the anticoagulation and no-anticoagulation therapy groups, respectively

fibrin thrombi within the he small vessels and capillaries and extensive extracellular fibrin deposition.”

To date, Igneri said, the he clinical utility of abnormal coagoaging, thrombosis and severerity of illness remain to be e determined, but the American Society for Hematology (ASH) reports that elevated D-dimer at admission and markedly increasing D-dimer levels (three- to fourfold) over time are associated with high mortality, “likely reflecting coagulation activation from infection/sepsis, cytokine storm and impending organ failure.

“COVID-19 thrombotic risk is increased by high circulating viral RNA loads, leading to endotheliitis, hyperinflammation—with a higher degree of tissue damage seen on pathology than expected—and platelet dysfunction,” Igneri explained. “These patients have a true hyperinflammatory response.”

Igneri suggested taking the following steps for managing anticoagulation in COVID-19 patients: 1. Follow the evidence. Igneri said a good place to start is an observational cohort study involving more than 2,700 patients with COVID-19 who had been mechanically ventilated. The study showed that patients who received anticoagulant therapy had a significantly reduced mortality rate (29.1%) compared with those who did not (62.7%). Longer duration of anticoagulant treatment was also associated with ment was also associated with reduced mortality (adjusted hazreduced mortality (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.86 per day; 95% CI, ard ratio, 0.86 per day; 95% CI, 0.82-0.89; 0.82-0.89; P P<0.001) ( <0.001) ( (J Am J Am

Table. Ta Tabl ble e. Modified Mod do if fi ie ed IMPROVE VTE Risk IM MI P PR ROV OVE VT VTE E Risk ks Score S Score

Risk Factor VTE Risk Score

Previous VTE 3

Known thrombophilia 2

Current lower limb paralysis or paresis 2

History of cancer 2 ICU/CCU stay 1

Complete immobilization ≥ 1 day 1

Age ≥60 years 1

VTE, venous thromboembolism

Coll Cardiol 2020;76[1]:122-124). However, there was no difference in in-hospital mortality for COVID-19 patients ulation tests to predict bleeded-

cally review patient charts and perform patient care activities from home. Some who normally (22.5% vs. 22.8%).

2. Look to treatment guidelines.

This can be helpful when deciding on a clinical strategy for VTE prophylaxis in COVID-19 patients. ASH recommends that, in the absence of bleeding, all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 receive standard prophy-

lactic dosing of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). For patients with contraindications to anticoagulants, mechanical VTE prophylaxis, such as elastic compression and intermittent pneumatic compression devices, is the only other option. “Combining chemical and mechanical prophylaxis is not recommended,” Igneri said.

3. For dosing clues, learn from oth-

er centers. Igneri noted that Cleveland Clinic has an algorithm that uses D-dimer and point-of-care ultrasound to determine the most appropriate anticoagulant dosage. If the D-dimer level is <3µg/mL FEU (fibrinogen equivalent units), a standard dose of LMWH is given and D-dimer is reassessed every ed every 48 hours. If the level is ≥3µg/mL FEU, mL FEU, the next step is ultrasound. If VTE is f VTE is detected, the patient receives therapeutic anticoagulation; if findings are negative or ultrasonography is not available, the patient receives high-intensity prophylaxis. “There is a preference for enoxaparin when available,” she said.

“It’s important to recognize that you may just need to treat this patient if you have a very high suspicion for VTE, even if you can’t get a confirmatory test,” Igneri said, “particularly if the patient rapidly deteriorates from a pulmonary or cardiac standpoint, or shows rapid change in neurologic function or sudden, localized loss of peripheral perfusion. At our institution, during the peak of our surge, we had many cases of pulmonary embolism, MI and ischemic stroke in COVID-19 patients with no other real risk factors.”

4. Be ready for extended therapy.

In some cases, extended thromboprophylaxis may be needed after a patient is discharged, Igneri noted. Although it is not routinely recommended, this strategy may be beneficial on a caseby-case basis, she said. A recent retrospective analysis of data from the MAGELLAN study on in-hospital thromboprophylaxis looked at the efficacy of extended thromboprophylaxis for VTE after discharge, using the modified IMPROVE VTE risk score (Table). The investigators found that patients identified as high risk for thromboembolism, with a score of 4 or more (or 2 and 3 with an elevated D-dimer greater than twice the upper limit of >2 times the upper limit of normal) had a significantly reduced incidence of VTE when prescribed a post-discharge course of up to 35 days of rivaroxaban (relative risk, 0.68; P=0.008) (TH Open 2020;4:e59-65).

“It’s very important that we think about what happens to COVID patients once they leave the hospital,” Igneri said. “At the time of discharge, consider the patient’s VTE risk factors, ing risk, when deciding whether or not ing risk, when deciding whether or not to initiate extended post-discharge to initiate extended post-discharge thromboprophylaxis.” thromboprophylaxis.”

In South Texas, Managing 100% of COVID-19 Remotely

Pharmacists don’t always have to be on the front lines to make a difference in COVID-19 care; they can play effective roles remotely, according to a study presented at the ACCP annual meeting. When COVID-19 cases began rising in Bexar County, Texas, in March 2020, all acute care clinical pharmacy specialists with the South Texas Veterans Health Care System, in San Antonio, were deployed to 100% telework to conserve the hospital’s limited PPE and reduce patient and employee exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, said Dana Douglass, PharmD, BCPS, a clinical pharmacy specialist with the medical center.

Strategies for communication were left to the pharmapharmacists, who were granted remote access to electroniincluding reduced mobility and bleed-

participate in daily bedside rounds in areas like internal medicine, cardiology and infectious diseases instead participated in rounds by listening g over the phone. Some chose to talk with clinicians s before or after rounds, or used internal instant messsaging platforms to contact physicians with medicaation recommendations.

Patient education also took place over the phone, , with pharmacists calling patients on their cellphones s or the phones assigned to hospital rooms. In cases s

Maryland Pharmacy Relies on IV Robots, Batch Compounding to Cope

As the COVID-19 pandemic surged in spring 2020, the pharmacy at the University of Maryland Medical Center, in Baltimore, faced several challenges affecting inventory management and pharmacy operations. By tweaking its in-house IV robot compounding process and transitioning to making some highly used products in batches instead of patient-specific doses, the pharmacy team quickly accommodated emerging inventory needs.

The main challenge was to come up with solutions that worked for both under- and overstocked medications— both of which occurred, paradoxically, as a result of the panemic. For example, inventory for many normally used medications such as succinylcholine and phenylephrine accumulated because of a fall-off in patient admissions and surgical procedures, Yevgeniya Kogan, PharmD, the hospital’s sterile compounding operations manager, said during the ASHP annual meeting. Other drugs, such as hydromorphone IV bags, went into critical shortages because they were being purchase from 503B vendors, many of which had supply chain issues. many of which h

The pandemic itself both increased The pandem demand for critical care products demand fo and generated staffing problems, as some employees stayed home to provide child care or because of a need to quarantine after potential exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

To overcome these challenges, Kogan and her colleagues quickly learned to adapt, turning to systems already in place for in-house IV compounding processing by robots, an inventory batch management analysis strategy and a prescribing trends review.

First, Kogan reviewed the pharmacy’s production schedule to make sure all compounds were still needed, flagging neostigmine for potential removal. The medical center typically used 700 syringes of the drug per month, but only 243 syringes were being used at the height of the pandemic. As COVID-19 evolved, the medical center was seeing a high demand for IV infusions of azithromycin 500 mg, cefepime 6 g, epinephrine 8 mg, furosemide 200 mg, hydromorphone 20 mg, pantoprazole 80 mg and rocuronium 400 mg. She and her colleagues determined they needed an estimated 600 weekly doses of these drugs combined and created a new schedule to batch the medications, in which hydromorphone and epinephrine would be produced by the IV robots while the remaining five products would be made manually by pharmacy technicians. They produced 8,547 doses of these medications in March through April and 11,464 doses in April through May.

During this period, the pharmacy team continued to carefully monitor inventory of these and other needed medications produced by the robots, such as heparin and vancomycin, including what was on hand and what was expected to be released from their quarantine process each week. They tried to keep three weeks’ worth of extended-dated IV robot products available at all times to account for any increase in demand or production issues.

From June through July, the pharmacy had steady use of azithromycin, pantoprazole and furosemide, and decreases in the need for cefepime as the number of COVID-19 patients began to fall, and in rocuronium as the preferred paralytic agent shortage resolved. Among the robotic compounded products, hydromorphone remained in high use. In contrast, the team temporarily stopped production of hydromorphone because one vendor shipped four weeks’ worth of back-ordered product that had been on shortage.

Among other robotically made products, rocuronium syringes also experienced a significant shortage due to insufficient vial supply, so the pharmacy had to be wise in managing inventory, Kogan said. They were able to get one of their vendors to outsource the product to stay ahead of the need, she noted. When the vial shortage stabilized, the pharmacy quickly resumed production.

By using these strategies, the pharmacy estimated a cost savings of more than $37,000 in April, over $45,000 in May, about $4,500 in June and about $8,600 in July from producing drugs as needed and not having them sit on the shelf and expire. “It’s important to develop a dynamic inventory review to adjust quickly to whatever is thrown your way,” Kogan advised. “And an IV robot compounding program may help buffer the pharmacy department from 503B vendor product shortages.”

It’s also important to be adaptable. During the current surge of COVID-19 cases, she noted, the Maryland team had to take another careful look at all of their compounding and inventory management strategies and make the necessary adjustments to ensure proper stocks. “It hasn’t been easy to balance that with surging patient care needs, but at least we have tools in place from our experiences in the Spring,” Kogan said. “So far, we are managing to stay about one step ahead of the flood.”

where pharmacists could not connect with where patients, they asked physicians to provide patie patients with information sheets on toppa ics like anticoagulation. ic Douglass and her colleagues observed workload metrics for 10 acute care clinical pharmacy specialists from the six weeks prior to implementation (Feb. 10-March 20) and the six weeks after (March 23-May 1). Chart notes increased by 39%, from 533 to 742 total notes. Interventions tracked by a documentation tool increased by 57%, from 350 to 549, for an estimated cost savings of $24,741 during the second phase. It’s likely pharmacists were intervening more all along but had less time to document their work due to time spent on rounding or other activities, Douglass said.

Since study completion, although the pharmacists have begun rotating back on-site, there is talk about implementing some long-term work-from-home arrangment. “There are going to be beneficial aspects of making interventions face-to-face,” Douglass said. “But this was successful because our pharmacy service had been in place for a long time, and we have built rapport with physicians, so they were receptive to our recommendations no matter the format.”

The internal messaging system also was helpful, she said. With physicians frequently rounding, visiting patients or doing other things, pharmacists could always reach them.

—Karen Blum, Bruce Buckley and Gina Shaw

The sources reported no relevant fi nancial disclosures.

More on the Web

A daily dashboard helps streamline medication management during COVID-19. For details, access an expanded version of this article on pharmacypracticenews.com.