11 minute read

Drug diversion: yet another pandemic challenge

Amid COVID-19, Fight Against Rx Diversion Continues

An updated set of ASHP Guidelines on Preventing Diversion of Controlled Substances, planned for 20212022, will help hospitals implement best practices using newer technologies.

“Our new version will review and evaluate market improvements” targeting diversion from many angles, David Chen, MBA, BS Pharm, the assistant vice president for pharmacy leadership and planning at ASHP, told Pharmacy Practice News.

Since 2017, when the first ASHP guidelines (bit.ly/35xqz8v) and 100-point hospital self-assessment test were issued, diverse technologies have reached the market, including: • analytical and artificial intelligence platforms that detect and track anomalous behaviors; • radiofrequency identification (RFID) labels from manufacturers that track medications from the source until administration to patients; and • waste tracking systems.

The updated guidelines from ASHP aim to address “1,000 points across a hospital where diversion could happen, from procurement to preparation and dispensing, to prescribing, administration and waste removal,” Chen said. “Every time you implement a process or tech-driven solution, someone figures out a potential way around it.”

The stakes are high for solving or at least mitigating diversion, because the illegal activity poses risks to people who divert as well as the entire health care system, Chen noted. In response, health systems are deploying a wide range of anti-diversion tactics. “They have compliance and regulatory departments, and many are also establishing multidisciplinary controlled substance diversion prevention programs that involve senior leadership because they often require additional resources and policy changes,” he said. “Early adopters also invest in robust analytics and automation.”

Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), in Boston, and Children’s Mercy Hospital, in Kansas City, Mo., are two institutions on the leading edge of such anti-diversion efforts.

Mass General’s Approach

At Massachusetts General, the added difficulties of caring for COVID-19 patients drove “higher diversion surveillance efforts overall,” said Christopher Fortier, PharmD, the chief pharmacy officer. Those efforts included an inventory audit following the hospital’s springtime surge “to ensure we accounted for the increased amounts of controlled substances we had to purchase” for the care of the sickest COVID-19 patients, he noted. The hospital’s annual mid-year audit focused on fentanyl, hydromorphone, lorazepam, methadone, midazolam, morphine and oxycodone.

Although many factors may contribute to diversion, Fortier cited a few likely culprits. During the first COVID-19 surge last year, MGH had to make rapid adjustments to workflow and other key operations. For example, “we converted general care units to ICUs, and needed nurses and physicians who don’t normally work in the ICU to staff those areas,” he said. Such changes could contribute to breakdowns in the normal checks against diversion, he noted.

Coupled with the added stress on health care practitioners, Fortier noted, these factors could explain why institutions have seen more discrepancies and overrides for controlled substances.

The response at MGH, where 4,000 nurses administer more than 2 million controlled-substance doses annually, was to “purchase the next generation of [a] controlled substance surveillance system that uses machine learning algorithms. We’ll implement it probably in early 2021. Pharmacy will take the lead on managing it, working very closely with nursing and anesthesia,” Fortier said.

“Technology like this is so new that the jury is still somewhat out—though I do know I want a machine learning system to help me identify a diverting worker in possibly a much shorter time frame, and I don’t want to weed through thousands of transactions each day. I want to see the exceptions pulled out of the system each day that show discrepancies and warrant further investigation. Machine learning brings in advanced algorithms to find those exceptions and saves an immense amount of time looking for the needle in the haystack.”

Fortier noted that soon after he came on board at the facility, he was tasked with “cleaning up” after the hospital paid the Drug Enforcement Administration a $2.3 million fine to resolve drug diversion allegations in September 2015. The health system agreed to implement a comprehensive corrective action plan lasting until September 2018. He noted that his institution’s multifaceted, evolving program is based on a culture he implemented “where people know this is serious, that we report appropriately, look out for peers, and put patients and care quality first so they’re never affected by diversion, as far as we know.”

Hospital leadership’s interest in the program and in its multidisciplinary collaboration components “remains high,” Fortier added. “We’re always working to get better.”

The anti-diversion program includes the following: • An interdisciplinary team of pharmacy, anesthesia and nursing leaders, police and security, human resources, compliance, legal, occupational health and employee assistance. “If someone is diverting and cooperates with the investigation, we want to help them,”

Fortier said. • 1.5 FTEs who review drug surveillance data from technology and nursing leaders’ reports of anomalous behaviors (reported daily.) • There also are 170 automated dispensing cabinets (ADCs) with all drugs in individual pockets and blind counts, in which nurses don’t

A Sampler of Technologies That Curb Diversion

Kit Check’s Bluesight for Controlled Substances added two features to its pharmacy module in summer 2020: single sign-on enabling pharmacy staff to access a full suite of solutions without another password, and system benchmarking to drive improvement and standardization of documentation practices across nursing floors and within ORs. BD HealthSight Diversion Management has a machine learning algorithm that looks beyond standard deviations to identify anomalous behaviors and help users correctly conclude investigations. “It does dynamic peer grouping. We compare like nurses caring for the same type patients with the same acuity level and opioid needs. It’s much cleaner to do it that way,” said Alan Frashier, RPh, CPh, MBA, the senior clinical sales consultant at BD. “This pulls it all together [rather than] connect dots that are very disparate in terms of what we ordered, what was pulled from the cabinet, what was actually charged to administer, and what may have been returned, canceled or wasted.” IntelliGuard Anesthesia Station is an RFID-automated medication management cart with end-to-end visibility of usable and end-of-life cycle medications. Users can customize tray pockets to accommodate ampules up to large IV bags; it has two-factor log-in and a biometric ID reader, emergency override access, a large touch screen monitor, and an automated Waste Witness module that issues audit reports, and it can integrate with electronic health records. Fresenius Kabi’s 20-mL vials of Diprivan (propofol). The product, launched in September 2020, ships with embedded RFID labels; prefilled syringes will follow by early 2021. The company said it plans to launch more than 20 other RFIDlabeled medications used in the OR. It claims it is the first pharmaceutical maker to embed medication identification data into the RFID tag following global GS1 standards, permitting full interoperability and compatibility.

Diversion Fight Defies Traditional Measures

Fighting drug diversion can be a tough battle. Here are a few key challenges cited by anti-diversion experts:

Results are hard to quantify. “How can you say how effective you are? You know what you did, but how do you really know what you prevented? It’s analogous to preventing medication errors,” said Christopher Fortier, PharmD, the chief pharmacy officer at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Costs are difficult to capture. The economic effects of drug diversion on hospitals are hard to quantify “because it is multifaceted,” said David Chen, MBA, BS Pharm, the assistant vice president for pharmacy leadership and planning at ASHP. “If a health care worker has an event, it involves human resources; if theft, it impacts time and involves law enforcement; if investing in technology, there is that cost and the time to implement; and there is the actual product loss.”

Scope is elusive. Diversion is widely underreported, and the illegal activity also extends beyond controlled substances, pharmacists and law enforcement sources have told Pharmacy Practice News. Indeed, 70% of 235 health care professionals surveyed in late 2019 by Porter Research for the Invistics 2020 Healthcare Drug Diversion Study said they believe most diversion incidents in the United States go undetected (bit.ly/ 3nKqXGX). Also, 86% of those surveyed said they have met or known someone who has diverted drugs, and 43% thought their organization could be at risk for fines, bad publicity, lawsuits or overdoses due to past or potential drug diversion.

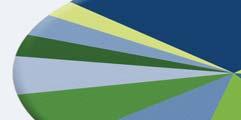

Still, some trend data are available. Amid the COVID-19 crisis, Kit Check aggregated secondquarter data from 52 health systems using its Bluesight investigations feature. Data showed 12%, or 1.35 million, of 11.63 million controlled substances dispenses had an unexpected variance in administration and waste. Of these, 111,236 transactions were elevated for more scrutiny after managers could not reconcile them. Investigations averaged 25.7 days from opening to their conclusion (See Figure at right for more data breakdowns.) s e y/ veyed eone who has their organization

—A.H. Fentanyl 23% of total

Midazolam 13%

Hydromorphone 12%

Morphine 11%

Lorazepam 9% Oxycodone 7% Hydrocodoneacetaminophen 5% Propofol 3% Ketamine 3%

Tramadol 2%

Figure. Top 10 drugs that make up variances.a

a Total does not equal 100%; only top 10 listed. Source: Kit Check data from 52 health systems using Bluesight investigative tool

know how many are in each pocket— all integrated with the pharmacy management and electronic health record systems. In addition, 90 anesthesia workstations document controlled substances waste within the pre-op, operative and post-op areas. • Drug testing of every newly hired employee is conducted.

Children’s Mercy Gets Proactive

Brian C. O’Neal, PharmD, helped draft ASHP’s initial guidelines to curb drug diversion, and he brought many of those best practices to Children’s Mercy Hospital, in Kansas City, Mo., where he serves as the senior director of pharmacy and biomedical engineering. Central elements of his program include:

An interdisciplinary controlled

substance oversight council. This group reviews details of any diversion incidents to improve the system. It also also establishes policies related to controlled substance handling and accountability.

An internally developed controlled

substance handling dashboard. This workflow software feature shows the numbers of discrepancies, overrides, transactions and events that might indicate poor practice and vulnerability. The software feature also confirms adherence to policies.

Overhead cameras. These are placed by all ADCs that hold controlled substances. The hospital system has 85 Cerner ADCs, which integrate with the Cerner pharmacy management system and Cerner electronic health records. “When you get an inventory discrepancy at an ADC, you don’t know for sure if the prior person caused it, or if the person who found it caused it,” O’Neal said. “Did one person access the return bin but not put anything in? Cameras put us at that location to help resolve discrepancies.”

A satellite pharmacy within one

of its two operating rooms. This setup tightens up waste procedures, so that “all controlled substances are returned to the OR pharmacy, where the anesthesia provider turns them in and watches with the pharmacist as they reconcile what was given out to them minus what came back,” O’Neal said. “We’re doing periodic sampling, but we’re working to transition to test everything that comes back after every OR procedure. Having a high-end refractometer or other analytic technology is also important.”

He added that Children’s Mercy is evaluating the potential addition of ADCs outside of each group of three to four rooms within the pediatric ICU. “We currently have three medication rooms with ADCs in our PICU. We discovered, though, that the distance from bedside to medication rooms, coupled with the highly acute nature of some of our patients, can lead to some highly undesirable handling practices [such as person-to-person handoffs and failure to waste in a timely fashion]. Although there is certainly cost associated with adding ADCs, we’re looking at whether these [units] would offer our nurses an additional tool to manage controlled substances in a compliant fashion, while being able to respond to the urgent needs of our patients.”

Although O’Neal said he is implementing an advanced analytics diversion detection software system, he still feels “there’s not yet strong data behind AI to prove that these new software packages have cracked the code on diversion. These systems have a lot of data, but it will likely take an end user to come up with a road map they can present or allow the vendor to share with other users. We have the tools, but aren’t quite sure of what to do with all of these data just yet.”

Closing the Loop

Michael Campbell, PharmD, MBA, the director of pharmacy services at Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center (PVHMC), in California, underscored the link between the stressors of the pandemic and drug diversion. Pharmacy workflow modifications made during a pandemic, he noted, such as those aimed at reducing virus spread, conserving personal protective equipment and limiting employee exposure to infection, can increase the risk for diverting behavior.

Campbell added that using softwareguided solutions makes sense. The technology, he noted, “requires users to complete steps to close controlled substances transactions.” The software also flags staff “who may need follow-up training in our controlled substance management processes.” —Al Heller