3 minute read

Richard Wyatt

Bath has always taken pride in its past through its famous architecture. Now there is an industrial dimension to our city’s heritage, revolving around cranes, engineering and an inventive building restoration, says columnist Richard Wyatt

Advertisement

There’s another side of the ‘coin’ when it comes to Bath’s first award of World Heritage status –inscribed by UNESCO back in 1987. One of the reasons for the accolade was the international recognition of our Georgian architecture and social history which grew out of the city’s prime occupation as a spa resort offering the wealthy an astonishing new collection of fine Bath-stone-built avenues and crescents to accommodate them.

We are still financially grateful to have our tourist ‘industry’ as a major source of income, but the original meaning of the word is wrapped around economic activity concerned with the processing of raw materials and the manufacture of goods in factories. That side of our local business has not been much lauded –that is, until now.

Hundreds of people toiled underground hewing the stone to build Georgian Bath. Hundreds more were to be employed at a local engineering factory which was to build for itself a worldwide reputation for making cranes. It’s a mechanical lifting device that would have been needed to shift those huge blocks of locally quarried limestone onto carts, canal boats and trains.

In March one of the oldest surviving cranes of its type will officially return to the place of its birth as a fitting memorial to the location of the famous engineering firm of Stothert & Pitt, described by Historic England as “the most famous crane makers in the world”.

This brings home a relic of Bath’s manufacturing heritage and will be the happy conclusion of years of effort and fundraising by a group of volunteers, including two former Stothert & Pitt employees, to restore a machine that spent its working life in the stone quarries of Box in Wiltshire. It dates from 1864 and is thought to be the oldest surviving crane built by Stothert & Pitt in the world.

The ‘resurrected’ crane is not the only way the city is finally coming around to acknowledging its working life alongside its Georgian elegance. This symbol of an industrial past won’t stand in isolation. Not all of the mighty engineering enterprise that was Stothert & Pitt has been swept away. Wisely, B&NES Council decided to allow the derelict remains of the once-famous Newark Works to form a major part of its Bath Quays enterprise zone AND the city’s economic future.

The Grade II listed complex has been carefully and sympathetically restored by regeneration specialist TCN and transformed into flexible office spaces that can accommodate anything from single co-workers through to companies of up to 40 staff. Everywhere you look there are echos of the building’s former past. Black-and-white photographs show the original empty shell, now brilliantly incorporated into the flagship redevelopment. Everywhere there is bare brick, original flooring and wooden beams. The remains of an overhead factory crane hook hangs down now over a coffee bar, lounge area and ping pong table.

Meeting places are named after famous types of crane like Goliath and Hammerhead. Glass is etched with the outlines of more modern dockside specimens still found in ports around the world.

I was lucky enough to be shown around and meet some of the people already moving in. The irony wasn’t lost on me that some of these were locally based start-up companies planning a business future in what was itself a Bath-based Victorian start-up enterprise.

Among those joining me on the tour was Simon Martin, the Director of Regeneration and Housing for B&NES. He told me: “Bath has few opportunities to celebrate its industrial heritage but this project is showing what Bath did for the UK and the world. I think we have struck the right balance between illustrating the historical importance of the building and its future use as an employment site.”

The renovated and reinvigorated building is joined on this new business quarter with a newbuild office block. No 1 Bath Quays has already welcomed two expanding local companies, with other lettings under serious discussion. Simon Martin explained: “Together, both enterprises could be looking to provide one thousand new jobs for the city.”

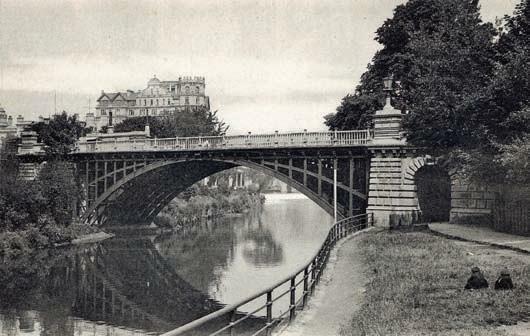

One of those businesses re-deploying from elsewhere has had to persuade its workforce to commute from other towns to Bath. They have been helped in this by the new pedestrian and cycle bridge that links this new business area with bus and rail transport hubs and the city centre.

This new link across the River Avon will have its official naming, and opening, ceremony in March. Old and new coming together to point a way forward for business in the city –while also utilising and celebrating the past. n