11 minute read

SURVEILLANCE IN MAINE

20

Brendan McQuade is an assistant professor in the criminology department at the University of Southern of Maine and author of Pacifying the Homeland: Intelligence Fusion and Mass Supervision (University of California Press, 2019). In addition to his academic writings, he has published commentaries in The Appeal, The Bangor Daily News, Counterpunch, Jacobin, and The Portland Press Herald. He is a member of the Democratic Socialists of America and on the advisory board of the Visionary Organizing Lab.

Advertisement

21

SURVEILLANCE IN MAINE

BRENDAN MCQUADE

In the last twenty years since 9/11, surveillance capacities of the US government have surged, transforming the country: a proliferation of new government organizations and companies focusing on counterterrorism, homeland security and intelligence; the widespread application of new technologies like automated license plates readers, facial recognition surveillance, IMSI catchers for intercepting mobile phone traffic; and new culture of generalized suspicion. The art exhibit Monitor: Surveillance, Data, and the New Panoptic at Maine College of Art & Design’s Institute of Contemporary Art provides an aesthetic exploration of this increasingly ubiquitous surveillance. While most discussions of surveillance focus on the federal government or large cities, the impact of the post-9/11 surveillance surge extended to all corners of the country —including the mostly rural state of Maine.

In 2011, investigative reporters William Arkin and Dana Priest surveyed what they called “top secret America.” They counted over one thousand government organizations and nearly two thousand private companies focusing on security and surveillance in at least 17,000 locations across the United States. Much of this sprawling security apparatus is hiding in plain sight: a National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency office in the shadow of a Michaels craft store and a Books-A-Million, an annex of the National Security Agency near a parking garage in the Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport, an “alternative geography” of official secrets hidden in plain sight. 1

The central node of “top secret America” in Maine is the Maine Information and Analysis Center (MIAC), the state’s “fusion center.” While the federal government, through the Department of Homeland Security, encouraged the creation of fusion centers, they are operated by state and local authorities. The Maine State Police are

22

the lead agency at the MIAC but personnel from federal, state, and local agencies fill out the staff. There are now eighty fusion centers throughout the country. They are good examples of the pervasiveness of contemporary surveillance. Fusion centers are analytic nodes in information sharing networks. While managed and staffed by police, fusion centers have agreements with other entities that allow them to remotely access their records. They buy databases from private brokers. They develop new data sources from technologies like automated license plate readers. Using specialized software, intelligence analysis creates sophisticated intelligence products from massive datasets: social network analyses, various forms of mapping, and visualizations of telephony metadata. Fusion centers, then, share this information and intelligence with other government agencies and the private sector.

The MIAC is located in a drab office park in Augusta, Maine that includes other government offices and Maine General Express Care. For the first nine years of its operation, there was no public information about its budget, staffing or exact location. Initial public scrutiny came in 2015, when then-Governor LePage made the MIAC the centerpiece of the state’s anti-drug efforts. 2 In 2020, dramatic events drew back the curtain of secrecy. In May, a former state trooper blew the whistle, alleging that the MIAC had spied on peace and environmental activists, maintained an illegal database of gun owners, and violated privacy laws concerning data retention and sharing. 3 A month later, as the wave of Black Lives Matter protests swept the nation following the police murder of George Floyd, another scandal hit: BlueLeaks. Distributed Denial of Secrets, a transparency collective, published 269 gigabytes of data hacked from Netsential, a private contractor that administered 251 police websites. The massive disclosures included 5 gigabytes of MIAC documents. The leaks confirmed the whistleblower’s allegations that the MIAC monitored environmentalists opposing the Central Maine Power Energy Corridor. It also focused attention on four “Civil Unrest Reports” on Black Lives Matter Protests in Maine. 4

In terms of fusion centers, the intelligence on protests were “situational awareness reports.” They were not part of an investigation. No informants were involved. Fusion center analysts gathered open source data and intelligence reports from other agencies in order to brief law enforcement on the public safety issues presented by the protests. In practice, however, situational awareness means sharing unsupported claims. All the “Civil Unrest Reports” warn of “Possible prestaging of bricks for access during Maine-based protests” and include a document from FBI’s Boston Field office that cited a Facebook screenshot attached as source. Nathan Bernard, a reporter with the Mainer, followed this lead. He found that the Facebook page cited in the FBI document

23

ANN MESSNER, the free library and other histories, 20 pages, offset tabloid, printed on 50lb white newsprint, 3rd edition, 2000 copies 12.5 ✗ 17 in. (each), 2018–2021.

24

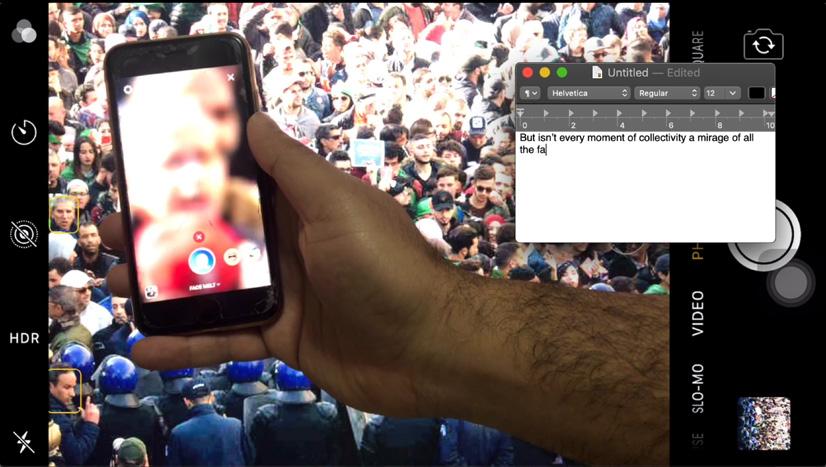

YAZAN KHALILI, Medusa, 6 channel video installation, 21:57 min., 2020.

is owned by an individual with connections to hate groups who refers to himself as “The Wolfman.” 5

This is just the tip of the BlueLeaks iceberg, however. The disclosures flooded the public record with nearly three thousand documents. Over 1,300 were either produced by the MIAC or shared with at least some of their 4,526 registered users. Nearly 80 percent of the documents created or shared by the MIAC concern the sharing of what is called “criminal intelligence.” Individually, each document is a fragment of a larger, incomplete story: a “wanted juvenile” who left a group home run by a private, for-profit service provider for people with “mental illness and/ or intellectual disabilities;” an “Armed…Maine (ME) resident living in the woods…reportedly suffering from mental health issues;” a “couchsurfing transient” with “several mental health issues (including his own claims of being bi-polar) and is off his medication(s).” Taken together, they reveal a coherent pattern: the punitive regulation of social problems through policing and surveillance. While the United States’ unparalleled incarceration rate and shocking levels of police violence rightfully dominate public discussions of the criminal legal system, mass surveillance is humming

25

in the background. Fusion centers and similar surveillance and intelligence programs are the nerve system of carceral state. 6

The MIAC documents and the poor souls caught in the clumsy dragnet of mass surveillance underscore an important point about surveillance. Surveillance is administration, the management of people and things through the control of information within hierarchical relationships, organizations, and societies. While shocking specifics of contemporary technologies give surveillance the appearance of novelty, the basic process is old. In 17th century Europe, rulers first began to apply the new science of statistics to the problems of government. They redefined life as information and the body as an information technology, creating the opportunity for individuals to be policed through information that institutions produced about them—usually without their consent or knowledge.

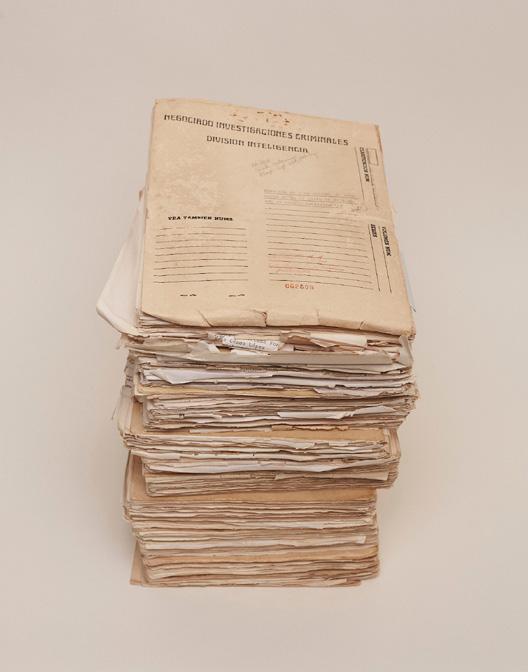

Several of the works included in Monitor: Surveillance, Data, and the New Panoptic explore these very issues. Kapwani Kiwanga’s Glow confronts the brutal history of racial surveillance with a meditation on the 18th century lantern laws that forced black and indigenous enslaved people to carry a lit candle after dark, if not accompanied by a white person. Works from Ann Messner and Christopher Gregory-Rivera repurpose dossiers, akin to those MIAC files published in BlueLeaks, explore the socio-political implications and psychological effects of surveillance. Both regard the FBI’s notorious COINTELPRO program that targeted every major social movement in the mid-century United States. For example, Messner repurposes FBI files on W.E.B. DuBois, renowned social scientist and black radical, and Gregory-Rivera uses the cache of 16,000 dossiers created to monitor and suppress the movement for Puerto Rican independence.

Other exhibits reflect on specific surveillance technologies, some of which have been subject to intense debate in Maine. Yazan Khalili’s video installation Medusa engages with practices of digital archiving in times of political unrest through a reflection on facial recognition technology. This surveillance system matches images of an individual face, captured by photo or film, against a database of known identities. What makes facial recognition particularly controversial is the potential for automated, suspicionless surveillance that could be used to track individuals wherever they go. When linked with the massive databases—the kind that fusion centers aggregate and analyze—facial recognition technology can link a person to their data double, records aggregated from the electronic traces left when you go about your normal activities. 7

While law enforcement and other proponents claim that facial recognition holds immense potential to protect “public safety,” it also threatens to change basic dynamics

26

of social interaction. The potential abuses and impact of facial recognition technology has led to a significant push to ban the technology before it becomes widely used and Maine has been at the forefront. The Portland City Council first considered the issue in November 2019 but tabled the issue for further study. 8 In this context, the Maine chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America launched a successful campaign to get a referendum for a municipal ban on facial recognition on the November 2020 ballot. In August 2020, with the referendum on the ballot and political sentiment shifting with the Black Lives Matter protests, the city council returned to the issue and banned facial recognition surveillance, making Portland the first city outside of California or Massachusetts to ban the controversial technology. 9 In November, Portland voters passed the referendum, which strengthened the ban. 10 In June 2021, the Maine House and Senate passed the strongest statewide facial regulations in the country. Facial recognition is prohibited in all areas of government and strictly regulates law enforcement use. Under these new rules, law enforcement may request a facial recognition search from the FBI and the state’s Bureau of Motor Vehicles (BMV) if they have probable cause to believe an unidentified person in an image has committed a serious crime. 11 That same legislative session, a bill to close MIAC—a first in the nation proposal to shutter a fusion center—passed the House but failed in the Senate. 12

These legislative actions speak to a growing awareness of surveillance and ill-effects throughout the country and here in Maine. These issues will not go away, nor will the contention and controversy that surrounds them. This exhibition is an opportunity to approach surveillance from aesthetic angles and reflect upon its multiple implications.

1. Dana Priest and William M. Arkin, Top Secret America: The Rise of the New American Security State (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2011),67, 86.

2. Steve Mistler, “Secretive fusion center to play key role in Maine drug crackdown.” The Portland Press Herald, September 6, 2015. https:// www.pressherald.com/2015/09/06/ secretive-fusion-center-to-playkey-role-in-maine-drug-crackdown/ (accessed September 9, 2021) 3. Judy Harrison, “Maine State Police illegally collecting data on residents, lawsuit claims,” Bangor Daily News, May 14, 2020, https:// bangordailynews.com/2020/05/14/ news/state/state-agency-illegallycollecting-data-on-mainers-claimstrooper-in-whistleblower-suit/ (accessed September 10, 2021).

4. Megan Gray, “Hack included documents from secretive Maine police unit,” The Portland Press Herald, June 26, 2020. https://

27

www.pressherald.com/2020/06/26/hackincluded-documents-from-secretivemaine-police-unit/ (accessed September 10, 2021).

5. Nathan Bernard and Caleb Horton, “Teenager or Terrorist,” The Mainer¸ July 29, 2020. https://mainernews. com/teenager-or-terrorist/ (accessed September 20, 2021).

6. Brendan McQuade, “Police Surveillance is Criminalization and it Crushes People,” Counterpunch, October 15, 2020, https://www. counterpunch.org/2020/10/15/policesurveillance-is-criminalizationand-it-crushes-people/ (accessed September 10, 2021).

7. Kelly Gates, Our Biometric Future: Facial Recognition Technology and the Culture of Surveillance (New York: NYU Press, 2011).

8. Randy Billings, “Portland council again delays vote on facial recognition ban,” The Portland Press Herald, January 6, 2020. https:// www.pressherald.com/2020/01/06 / portland-council-again-delays-voteon-facial-recognition-ban/ (accessed September 10, 2021).

9. Randy Billings, “Portland councilors approve ban on facial recognition technology,” The Portland Press Herald, August 3, 2020, https://www.pressherald.com/ 2020/08/03/portland-councilorsapprove-ban-on-facial-recognitiontechnology/?rel=related (accessed September 10, 2021). 10. Nick Schroder, “Portland boosts minimum wage to $15 as it passes wave of progressive policies,” The Bangor Daily News, November 4, 2020. https://bangordailynews. com/2020/11/04/news/portland/ portland-boosts-minimum-wage-to-15as-it-passes-wave-of-progressive-pol icies/?fbclid=IwAR1ZpYSILIGo01kVJdLg F2afn59EbrYMGbPhZupQZ3uqLygiTDucnUtX 0ME (accessed September 10, 2021).

11. Dave Gershgorn, “Maine passes the strongest state facial recognition ban yet,” The Verge, June 30, 2021. https://www.theverge. com/2021/6/30/22557516/maine-facialrecognition-ban-state-law (accessed September 10, 2021).

12. Caitlin Andrews, “Bill to close Maine police intelligence-sharing center clears House, but stalls in Senate,” Bangor Daily News, June 14, 2021. https://bangordailynews. com/2021/06/14/politics/house-votesto-close-maine-police-intelligencesharing-center/ (accessed September 10, 2021).

/p.28–31 YAZAN KHALILI, Medusa, 6 channel video installation, 21:57 min., 2020.

CHRISTOPHER GREGORY-RIVERA, Las Carpetas, installed wallpaper, 112.25 ✗ 90 in., 2014–. Las Carpetas, Untitled, archival inkjet photograph, 16 ✗ 20 in., 2014. Las Carpetas, Untitled, archival inkjet photograph, 16 ✗ 20 in., 2014.

34

The Carpeta of Juan Ángel Silén who was the founder of the Federation of Pro-Independence University Students or FUPI.

CHRISTOPHER GREGORY-RIVERA, Las Carpetas, installed wallpaper, 72 ✗ 90 in., 2014–. Las Carpetas, Untitled, archival inkjet photograph, 16 ✗ 20 in., 2014. (Detail Above)

Las Carpetas, Untitled, archival inkjet photograph, 16 ✗ 20 in., 2014. Las Carpetas, Untitled, archival inkjet photograph, 16 ✗ 20 in., 2014.

36

KAPWANI KIWANGA, Glow 2, wood, stucco, acrylic, steel, LED lights, 59 ✗ 23.75 ✗ 8 in., 2019. ©2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Glow 3, wood, stucco, acrylic, steel, LED lights, 69.75 ✗ 39.5 ✗ 10 in., 2019. ©2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

37