18 minute read

Soul enterprise

Job One

Spirituality for the “piety impaired”

“Why would we want to look for God in our work? The simplest answer is that most of us spend so much of our time working that it would be a shame if we couldn’t find God there. A more complex reason is that there is a creative energy in work that is somehow tied to God’s creative energy. If we can understand and enter into that connection, perhaps we can use it to transform the workplace into something quite remarkable....”

So says Greg Pierce, a Chicago publisher who is author of the article on page 12 of this issue.

Pierce, who describes himself as “piety impaired,” says he buys into a spirituality of work that grows out of the work itself and connects with the God who is always present in our places of work. “This kind of spirituality,” he writes, “has little to do with piety and much more to do with our becoming aware of the intrinsically spiritual nature of the work we are doing and then acting on that awareness. Authentic spirituality – at least in the Judeo-Christian tradition – is as much about making hard choices in our daily lives, about working with others to make the world a better place, and about loving our neighbor and even our enemy as it is about worship and prayer.”

His definitions:

Spirituality: “A disciplined attempt to align ourselves and our environment with God and to incarnate (enflesh, make real, materialize) God’s spirit in the world.”

Work: “All the effort (paid or unpaid) we exert to make the world a better place, a little closer to the way God would have things.”

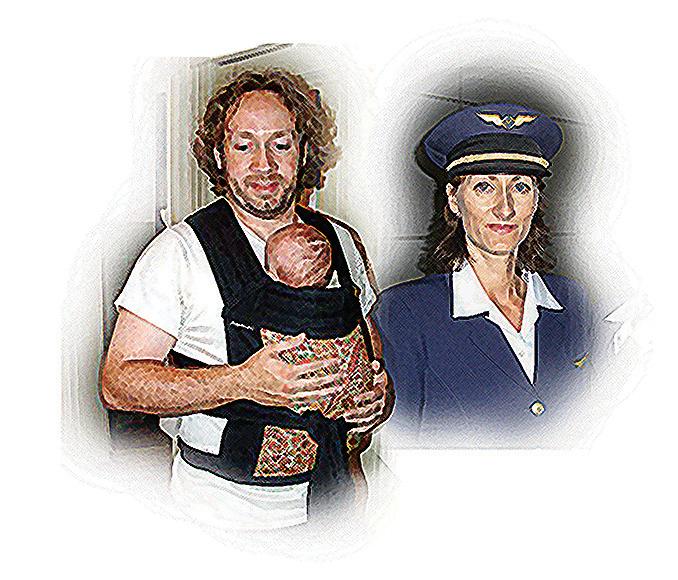

Spirituality of work: “A disciplined attempt to align ourselves and our environment with God and to incarnate God’s spirit in the world through all the effort (paid and unpaid) we exert to make the world a better place, a little closer to the way God would have things.” (God@Work) Want the best job in the world? Examine your own skills and interests and see how they intersect with what God is doing to sustain human society and maintain the fabric of the world, writes Thomas Long: “Whether it is piloting a plane full of passengers from Minneapolis to Chicago, teaching a class of third graders, changing the diapers on a newborn, entering data into a computer, studying for a chemistry exam, or repairing a leaky faucet, the best work in life is work that we can understand as part of what God is doing in the world.” (Testimony: Talking Ourselves into Being Christian)

“What did you do at work today, Daddy?”

Paul Cottle loved his job with a Canadian satellite company. He looked forward to Monday mornings. Then he learned that his employer was being sold to a corporation known for manufacturing land mines and cluster bombs. He wrestled with his conscience and decided “I just don’t want to be part of it.” So he quit.

Other people might also face a dilemma if their work is seen to harm life rather than enhance it. Such decisions aren’t easy or black and white.

Want a quick way to test your work? Here’s a two-part test that business professor Gerard Seijts uses in his management classes: 1. If your work was featured on the front page of the newspaper, would you be proud of it? 2. If you tried to explain your actions to your 10-year-old child, could you honestly sell it? (Globe & Mail)

Taxi, taxi

“Cab drivers, listen to this message: You are a priest at the wheel, my friend, if you work with honesty, consecrating that taxi of yours to God, bearing a message of peace and love to the passengers who ride with you.” — Oscar Romero (1917-1980), archbishop of El Salvador

Jalopy justice

Car salesman Robert Chambers got ticked off one day when a colleague sold an overpriced, high-mileage junker to a single mother who earned $11 an hour. Since she had some credit problems she was talked into a high-interest loan that would last years longer than the car.

The dealership made $5,000 profit. Chambers knew it was a rip-off.

“I just couldn’t stand it anymore,” he says.

Instead of retiring, he decided to use his years of expertise to help unsophisticated buyers who often get the short end of such transactions. He started a new business called Bonnie CLAC (“Car Loans and Counseling”) to give lower-income people better deals plus some forthright counsel on the hidden ways car costs can add up.

Bad car deals can keep a struggling family from getting traction, says Chambers. You can’t get to work if your car breaks down, and you lose wages you need to pay for repairs. But a good car can reverse that cycle.

He brings in well-maintained used cars and arranges loans with a local bank so that even clients with lackluster credit can get a decent rate. He rarely gets stung even though the loans would seem risky. “Our success rate is better than commercial lending,” he says. “On a portfolio of $10 million with 985 clients, we’ve lost $46,000.”

Chambers plans to expand Bonnie CLAC across New England, maybe even nationally. For him, retirement is on hold; he’s having too much fun making a difference. (Steve Tripoli) “One thing that makes my heart beat is the smell of drywall. I love to look at something and see what it can become.” — T.L. Rogers, pastor of a Baptist congregation in Maryland whose ministry includes urban renovation projects

Contesting for the faith

Here’s a nice way to affirm faith-infused companies. The Catholic Spirit, published in St. Paul, Minn., holds a “Leading with Faith” contest for which Twin Cities residents can nominate anyone “whose business practices reflect the teachings of Jesus Christ and the church.” Winners must be from a just company that delivers a quality product or service. This year’s winners came from the bus, insurance, banking and construction sectors. (Initiatives newsletter)

Overheard: “A person’s wallet is like a spiritual diary.” (Pete Hammond)

Return of the native

The Soviets took his father and evicted his family, but when a window opened Harry Giesbrecht returned to do business. Now nearly 80, he still keeps up a feverish pace to help repair and restore his homeland.

by Wally Kroeker

The train still rumbles through Lichtenau, Harry Giesbrecht’s birthplace in the heart of Ukraine’s historic “Mennonite region.”

It carries passengers and freight, but not nearly the throngs of the 1920s. Then its cargo was Mennonites. Lots of them.

The mainline station on the edge of the village holds a mystical grip on the memories of Mennonites who gathered there in droves to escape the unfolding Bolshevik tyranny. That was where thousands of them clambered aboard with their few possessions, leaving behind homes, farms and relatives as they headed for a new life in Canada.

You can still watch the train come through, but today there are no teeming crowds of emigrants, no tearful farewells, no mournful singing of hymns and prayers.

Harry Giesbrecht never made it onto one of those trains. By the time he came along the flow of emigration had ebbed. When he left, it was on foot.

Lichtenau was one of the first villages in the Molotchna colony, which was settled by Mennonites from Prussia in 1804. It was located a few miles south of Halbstadt, a larger administrative and educational center. For more than a century Mennonites flourished there. But that ground to an excruciating halt. At the age of four Giesbrecht was sucked into the swirling conflict of the Bolshevik Revolution. His father, who had been a bank manager and worked for a trade mission, was arrested as a political prisoner, dispatched to a prison camp and forced to work on the Trans-Siberian railroad. Giesbrecht’s mother and her seven children were ordered to leave. “We were thrown out of the house,” says Giesbrecht. “What is life all about if you can’t give?” says Winnipeg contractor Harry Giesbrecht. “We were allowed to take only what we could carry on our backs. So we walked. We walked for three days, sleeping in the ditch at night, to Melitopol, and spent a year there before moving to Mennonite Heritage Centre (NP07-01-7) Nikopol.” That was home until 1943 when they and many other Mennonites managed to get to Germany during the Second World War. The years were hard and hungry. “I never knew the feeling of a full stomach until I got to Canada in 1948,” Giesbrecht says. His father was eventually released from prison and

In the 1920s Mennonite emigrants flocked to the Lich- rejoined his family. “But he tenau station to begin their trek out of Russia. Menwas never the same after nonites would again depart from the Lichtenau Train that,” says Giesbrecht. “He

Station in the 1940s when they were being shipped was broken in spirit when he eastward by Communist authorities. came back.”

The years of flight and scrounging to exist were like something out of a refugee novel. He describes the gritty struggles in an accent thickly graveled with Russian, his first language.

The scars have not made him bitter nor dampened his lively wit. Instead, the memories seem to fuel his irrepressible spirit as he enthuses about the myriad projects he now carries on as a refugee who returned, who “made good” and now “does good.” There aren’t many folk around who do more business in Russia — or more mission. Stories abound of his free-flowing generosity: sending containers of supplies to orphanages, replacing a furnace at a village clinic, or digging deep to rescue a struggling business.

He doesn’t hesitate to point out the shortcomings of the system that nearly wrecked his family, but nor does he gloat. He has chosen a higher road — to share, repair and show a better way.

“What, after all, is life all about if you cannot give, and only take,” he says.

When Giesbrecht reached Canada it didn’t

take long to find outlets for his work ethic. He found a job at a Winnipeg sausage company but soon saw opportunities as an engineer, and worked for Manitoba Hydro designing substations for the emerging electrification of the province. become a premier contractor of grain elevators and dryers in western Canada and as far as China, Romania, Hungary and Egypt. When traditional grain handling facilities were supplanted by large regional terminals, Central Canadian Structures moved into other types of construction — factories, warehouses, schools and hospitals.

In the mid-1980s he was invited “out of the blue” to the Soviet Union to participate in a “technology exchange.” For three days his hosts picked his brains. “They took everything out of me that I had, and then I asked them to give, too.” But there was nothing forthcoming. The plainspeaking Giesbrecht told them, “‘This is not an exchange of technology, it’s a transfer of technology.’ So I went home.” Six months later he got a letter from the Trade Union, the biggest organization in the Soviet Union with 16 million members. “They owned every hotel and every resort, and now they wanted to know if they could host foreigners,” says Giesbrecht, who instantly saw this would be impossible without massive upgrading or rebuilding.

So they invited him to build a brand new 13-storey 365-room hotel in Leningrad (since re-named St. Petersburg), the second-largest city in the country.

That $10.5 million project was Giesbrecht’s first job there, and “I stayed ever since.”

The venture gave him media exposure as the first western company to work in the Soviet Union. He told the press that his purpose was more sentimental than financial. “It’s almost a case of revenge in reverse, of turning the other cheek,” he said at the time. “We have decided to forgive and help out because we believe the Soviets are sincere.”

One of the people he would encounter was a bright and serious young man who was deputy mayor of Leningrad. His name was Vladimir Putin. They would become friends (see sidebar).

When Harry Giesbrecht bought this school bus the whole village lined the streets to greet its arrival.

But even in his new land of freedom he encountered limitations. “Harry’s a fine engineer,” he overheard a supervisor say. “Too bad he’s German.” When he learned that this prejudice was more than lunchroom talk, he began to look elsewhere and soon found work with a growing construction company where his skills and entrepreneurial spirit could flourish. When the owner decided to retire, he offered the construction division to Giesbrecht on convenient terms.

Soon a new company was born in partnership with two other members of Giesbrecht’s Mennonite church. Called Central Canadian Structures Ltd., it would grow to

The hotel project was anything but easy.

Although Mikhail Gorbachev was in power, and the improvements of perestroika were evolving, conditions were still far from western standards.

“We had to import absolutely everything — even

nails,” says Giesbrecht. “There was no construction material except for gravel and cement, and even for that we had to use our connections with Putin. We imported supplies by the containerload.”

When he needed steel he asked for the metal specifications. He was appalled by what he saw. “We haven’t used that low a grade of steel for over 50 years,” he says. “They are behind in almost everything they do.

“Today we don’t take any construction material anymore. They have it there now, but it is all imported by them, because Russians He has mastered don’t produce anything. They are 50 years bethe art of getting hind.” things done in a Nonetheless, Giesbrecht relished the chalplace where da lenge, as well as the irony, of working back in the can mean nyet. homeland where he had once been unwelcome. He didn’t resist pointing it out to his hosts.

One day he and a group of other western businessmen were invited to a villa in the Caucasus mountains. During the festivities it fell to Giesbrecht to make some comments and thank his hosts.

“I told them I was going to say what was really on my mind. I said, ‘You probably know all about me. You know that you took my father away, that you destroyed my family. You took my oldest brother in 1937, never to be heard of again. You know all of this. And now you’re inviting me, as a businessman, to come and invest in your country. You know what I will suggest? I suggest you build a bridge across the Atlantic Ocean and that we meet on the middle of the bridge, throw our arms around each other, and say we are brothers. Our world is so small that it took Sputnik only 60 minutes to travel all the way around. Why are we enemies?’”

The Russians accepted his candor, and kept

inviting him. Over time he erected apartment buildings in Moscow and the Canadian embassy in Kiev. He built a 35,000-ton grain handling complex and 25 high-end Canadian-style homes in Dnepropetrovsk, once closed to outsiders because of the missile factory located there in Soviet times.

He says he can’t count how many buildings he constructed.

For years he traveled back and forth 16 times a year.

“Now I go only about 10 times; I’m supposed to be retired,” he says.

A few years ago he turned over Central Canadian Structures to his son, but he still handles the Russian work, which represents about 30 percent of the firm’s business.

Giesbrecht has mastered the art of getting

things done in a peculiar environment where da can mean nyet. Seasoned by years of operating under Soviet and

Rudy Friesen photo

Harry Giesbrecht at the crumbling walls of the house he lived in as a youth in Nikopol.

later mafia clouds, Giesbrecht can tell eye-popping stories of surviving in a murky climate where “You don’t get a dog licence without paying a bribe.”

His eyes sparkle as he grins and shakes his head. “It’s a strange world,” he says in a classic understatement. “I wouldn’t survive if I didn’t speak the language.”

As a man who knew his way around, Giesbrecht fielded countless requests from mission agencies that flocked to take advantage of the new openness of the early 1990s. He was always willing to help. He found

quarters for the staff of MEDA, Mennonite Central Committee and a Canadian Mennonite radio ministry. He opened doors for Campus Crusade and the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

His heaviest lifting would be for ventures closer to home — his original home.

Like Lichtenau, for example, which today has a population of 900. Giesbrecht singlehandedly refurbished its school system with computers and sent the teachers for special training.

He saw there was no bus for a school that served six villages in a four-mile radius.

“I told the mayor, a very honest, dedicated man. ‘Listen Petrau,’ I said. ‘You find yourself a bus and I’ll buy it for you.’ So he went to Melitopol and bought a bus. When he drove the bus in himself, the whole village lined the streets to welcome him.”

Then he noticed that elderly people had to walk three miles to the nearest clinic.

“I told the mayor to cooperate with me and clean up the village. I told him my childhood house no longer stood but the lot was still there. I said I’d like to build a house on that lot and bring the clinic in and put it in there, and upstairs we’ll have an apartment so maybe Harry Giesbre-

A friend of Putin

The walls of Harry Giesbrecht’s office hold a small gallery of mementoes from his life in business. There are photos of him with long-time Canadian politician Jake Epp as well as former Soviet leaders Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin.

There’s also one of Giesbrecht with current Russian president Vladimir Putin, recently selected as TIME magazine’s Person of the Year. Giesbrecht has been Putin’s friend and associate for nearly 20 years.

They met when Putin was deputy mayor of Leningrad (now renamed St. Petersburg). Giesbrecht was working with Atomic Energy of Canada, which was building a hydrogen plant nearby. Putin accepted an invitation to visit Canada and attended a barbecue in his honor at Giesbrecht’s home in Winnipeg.

The visit went well. One of Putin’s chief advisors even accompanied Giesbrecht to a worship service at Portage Avenue Mennonite Brethren Church. “He participated in the Sunday school class and asked some good questions,” Giesbrecht recalls. cht can stay there sometime.”

He is now an honorary citizen of the same community from which he was expelled in 1932.

His eyes glow brightest when he speaks of the Mennonite Centre in Molochansk (once known as Halbstadt). It is located in the old Mennonite Maedchenschule (girls school) which figured prominently in local Mennonite history and where his elder sister attended.

Giesbrecht and Winnipeg architect Rudy Friesen completely renovated the rundown building and restored its original glory. It now houses an active spiritual and humanitarian ministry, including language and computer training, and help for the elderly. Giesbrecht is also a member of the centre’s board of directors.

“I didn’t resist too much being roped into that project,” he says. “I was very happy to do it.”

The facility is a regular stop on the popular Mennonite Heritage Cruise tours (led by Walter and Marina Unger) which have enabled thousands of visitors to explore their roots.

Although his return to his homeland was ostensibly to do business, Giesbrecht’s charitable ventures outnumber his commercial enterprises. Each has its own reward.

Giesbrecht gestures to a photo of him with Putin and the advisor. “I sent him a copy, and Putin wrote back, ‘I remember you, my friend, and I will never forget you.’

“I got to know him very well,” says Giesbrecht. “I liked him.”

When TIME disclosed rare insights into Putin’s religious inclinations, Giesbrecht was not surprised.

“I got to know him as a religious man. We had quite a number of semi-religious discussions about morality. We quoted some Bible verses back and forth. We never disagreed on religion.”

The relationship continued after Putin became Russia’s president, though Giesbrecht notes he has not received a response to his most recent letter, which contained some pointed suggestions about the country’s future.

TIME described Putin as a man who makes no effort to charm visitors. Giesbrecht agrees.

“He talks very little. He answers your questions but he does not volunteer too much more.

“But he is extremely intelligent, and he’s honest. He says what he means and means what he says.”

Giesbrecht glances at the photos showing him with some of the most powerful men in the world.

“Power corrupts,” he says with a sigh. “Once you have this power, it’s hard to let go.” ◆