38 minute read

Soul enterprise

What’s the right job for you?

Maybe you’re just starting your career. Maybe you’re in a job but feel unfulfilled.

Don’t worry. The cement hasn’t hardened.

Young people entering the work force today can expect to change careers half a dozen times during their lifetime.

Sadly, some studies show that 60 to 80 percent of workers feel mismatched to their jobs. For Christians, that can be a spiritual issue.

“Choosing the job you long to do may be the most far-reaching commitment to Christ you can make,” writes David Frahm in The Great Niche Hunt: Finding the Work that’s Right for You.

He believes that natural interests, abilities and even limitations are part of God’s plan. That’s why it’s important to uncover “Who am I?” and to ask, “What do I really want to give my world through my work?” He suggests: (1) inventories to help identify how you process information, solve problems and influence others; (2) self-tests to help find suitable job environments; and (3) functional resumes to help articulate marketable skills to employers who can use them. Capitalism with soul

That doesn’t mean you should bail out of an entry-level job. It may be helpful — if you learn from it. The recent recruiting season has seen financial

Writer Tim Stafford had many menial jobs early in life — bus firms trying to win over student prospects by putboy, janitor, window washer and irrigation-pipe mover. He didn’t ting their best feet forward, reports The Economist. always enjoy them but he learned important lessons that have Aware that the financial crisis gave their reputations served him through life. “I learned how to keep at a job and not a black eye, firms are trying to show they have cut corners, even when nobody is watching. I learned that work- plenty of soul. ing hard at a job is actually easier than loafing at it.” Ever since the crisis, students reportedly have

Even low-skill jobs like flipping hamburgers can be helpful. become more concerned about the ethics of their “True, a job selling hamburgers won’t make a splash on your future employers. “Banks have cottoned on,” says resume,” says Stafford. “It will, though, teach you how to show the magazine, “placing much more emphasis on up on time, behave responsibly, do your duty without shirking social responsibility in their recruitment presentaand get along with your co-workers. With those lessons learned, tions. Prospective applicants learn that working for you’ll do all right in the working world.” a bank will help the global economic recovery and

At a different level, beware the lure of the fat paycheck. remedy social injustice.” Many people have gone into jobs (or kept them too long) Goldman Sachs’ recruiting messages target because of money. Choosing work solely on the basis of money those who are “interested in serving something can doom you to what writer Blaine Smith calls “a life of pros- greater than their own personal interest,” people perous mediocrity.” who want to “make a difference in the world.”

Putting financial considerations at the top of the list of Big firms are also promising to treat employees priorities is possibly “the most insidious factor keeping Chris- better. One “announced that its junior staff will tians from being where God wants them,” he says. “Many are no longer work between Friday night and Sunday promoted from a position where they are using their gifts to a morning — though they should still ‘check their better-paying, more respectable position which does not tap BlackBerrys on a regular basis’.” their potential as well. Before long they adapt to a more extravagant lifestyle that is difficult to give up. They can’t free themselves from ‘the golden handcuffs’.”

Another set of handcuffs comes from geographical inertia — staying where you are because you don’t want to move, whether that’s across town or across the country.

“Many of us will find the opportunity to use our most important gifts only if we’re willing to forge beyond our comfort zones,” Smith writes.

Excerpted from You’re Hired! Looking for work in all the right places, a career guide from MEDA. Available for free download at www.meda.org

?? ??? Monday morning quiz Here’s a list pf questions to ask about a job or company you’re considering. If you’re feeling brave, show it to your prospective employer. • What kind of reputation does this employer have in the community? • What are its values? Are they clearly stated? How do they line up with mine? • How does this company treat minorities, women, seniors, the disabled? • Is it family-friendly? [If you are married:] What price will my spouse have to pay? • Will I be proud or embarrassed to tell others that I work here?

Ask these questions about the job: • Will my Christian faith and values be a plus or minus for this company? • What’s the chance this job will require me to do something that goes against my principles? • Will the work I do help other people? • Does the job look interesting enough to keep me from getting bored? • Does it provide adequate support? • Does it use my gifts in a useful way? Will it give me a chance to grow (or at least look good on my resume later)? • Will this job make me a better person?

To lead ... or not

Are you a leader? If so, do you know why?

Good questions for anyone starting a career.

People complain about a “leadership crisis,” that we don’t produce as many leaders as we used to, or that we need college and seminary courses to help grow more leaders.

Do leaders ever wonder how they got that way? Were they born to it, like someone with perfect pitch? Did somebody make them a leader? If so, how could they be cloned?

A Mennonite official once said the art of leadership was to find out where people are heading and then run like mad to keep ahead of them. He may have been joking. Or not.

To management guru Peter Drucker, “The only definition of a leader is someone who has followers.” To one Mennonite seminary professor, “All of God’s people are leaders.” By leader he means anyone who seeks to influence others and make a difference in the lives of people around them.

Another view is more hierarchical — the leader as The Boss over a large number of people.

What are some duties of leadership? Long-range strategic planning, says one guru-of-the-month. Naw, says another, “that’s the task of managers; a true leader is more concerned with setting vision.”

One retreat leader sees leadership as influence, another as competence, and a third as “the ability to inspire confidence, to motivate, to know where you want to go and then convince others to follow.” A writer in Canadian Business summed up leadership attributes as graciousness, the ability to listen, discipline, vision, judgement. But, one could argue, someone with plenty of influence might lack grace and discipline. Someone of great competence might lack vision or judgement. How about this: “My favourite definition of a leader is someone who gets people to go places and do things that they would never go to or do on their own.” (David Posen in Is Work Killing You?) It can get confusing.

Overheard:

“Sheer competence is much underrated as a spiritual discipline.” — Haitian philosopher B. Boku

How will we feed them?

Convention considers more solutions for a harvest of hope

Imagine a world without bananas. Imagine growing tropical fruit in central Canada as climate change makes the prairies warmer and wetter. Imagine having to boost global food output by 70 percent by 2050.

Those were just a few of the scenarios painted by global food expert Robert L. Thompson in his leadoff address to MEDA’s annual convention, held Nov. 7-10 in Wichita, Kan.

The gathering, MEDA’s most visible annual event, drew a total of 509 attenders (376 full-time; 133 part-time) for a weekend of speeches, workshops, tours, a zany fundraising auction, and plenty of business networking.

The theme was “Cultivating Solutions: Harvesting Hope,” which lent itself not only to MEDA’s tagline (“Creating business solutions to poverty”) but also to the urgency of global food issues. It also suited the convention’s location in the breadbasket of the country, as well as MEDA’s increasing programmatic efforts to boost food production (soybeans, rice, cassava, etc.) in Africa and elsewhere.

Photo by Steve Sugrim

Thompson, a world authority on global

agricultural development and food security, is currently a visiting scholar at Johns Hopkins University and longtime professor at the University of Illinois. He presented a stirring, if somewhat bookish, address on the challenge of meeting food needs in a world that is growing by 200,000 people very day. Thompson said world food demand was projected to grow 70 percent between now and 2050 — not only from population growth but also from economic growth that triggers increased consumption as newly affluent people eat more and better. “By midcentury we need to feed the equivalent of two more Chinas,” he said. That is a formidable prospect, as right now one in eight people cannot afford a nutritional minimum of 1,800 calories per day, he added. The dual challenges were to, first, feed a growing population (most of whom will be in low income countries) at a reasonable cost without damage to the environment, and second, reduce extreme poverty in rural areas, where most of it is concentrated. Agriculture alone can’t solve the problem of rural poverty, he said. “To solve the world’s hunger problem, the world poverty problem must be solved.”

Seventy percent of extremely poor people live in rural areas where options for making more money are limited. They can gain access to more land, increase productivity of what they produce, or shift to higher value crops. Some of that is easier said than done, he said.

Farming more land was not the answer, as most available cropland was in remote areas of inferior soil and minimal infrastructure. Dramatically increasing the

amount of global land under cultivation could only be achieved by destroying forests with accompanying loss of wildlife habitat and biodiversity.

In his view, the only environmentally sustainable way to grow more food was to increase productivity, and those efforts were hampered by issues of water, climate change and public policy mindsets that seemed biased against meaningful progress. An example of the latter was politicians who, facing a constant stream of migration to urban areas, typically want to keep food prices low at the expense of farm sustainability.

“Cheap food policies designed to keep urban food prices low have turned the terms of trade against farmers, reducing the incentive to Farmers will have invest, and causing agriculture to underperform, to double “crop relative to its potential,” Thompson said. per drop” through A related issue was water. Farmers accountbetter water use ed for 70 percent of the world’s fresh water use, and drought- but with the pressure of urbanization cities will outbid agriculture for tolerant crops. more water, he predicted. Thus, farmers will have to double “crop per drop” through more efficient water use and more drought-tolerant crops.

He predicted that climate change will create more extreme events like droughts and flooding but not all regions will suffer the same. The Canadian prairies, for example, could reap some agricultural benefits from warmer weather and more water.

Thompson lamented that foreign aid for agriculture had gone in the wrong direction, declining in many categories between 1980 and 2005. More public sector investment was needed, not only for agriculture but also for roads, energy and telecommunications to enable better agricultural production.

One conclusion from Thompson’s speech

was that more adaptive plant breeding to build in drought tolerance and disease resistance was needed, in other words, more acceptance of genetically modified organisms (GMOs). While GMO crops were well entrenched in many North American sectors, they were less accepted, even banned, by some overseas countries. While Thompson was careful to say genetically engineered crops are not a silver bullet and “won’t solve all the problems,” he believed they had a role to play in “opening new frontiers” such as increased drought tolerance and resistance to disease and viruses.

“If we didn’t have GMO papaya we would not have papaya today,” he said, adding that bananas will be lost in 20 years if the benefits of GMO aren’t employed.

Governments had essentially ceded biotechnology to the private sector, which he felt had run away with the research. “There is nothing inherent in biotechnology that says it must be done by the private sector,” he said.

One way in which the issue had been distorted, and the actual science ignored, had been when private companies patented biotechnology and made people pay to use it. When it comes to GMO, he said, the scientific community is agreed that “the technology does not make food unsafe.”

The private sector, including farmer-owned coopera-

Photo by Steve Sugrim

“By mid-century we need to feed the equivalent of two more Chinas,” said opening night keynote speaker Robert Thompson.

tives, needed to build the marketing infrastructure, “but this will happen only if government provides a legal environment and public policies that create a positive investment climate.”

Many in the crowd seemed to agree with the steps he suggested for the future. Not all were as comfortable with his debunking of “phony research” that promoted certain ideological positions.

Thompson praised MEDA for its attention to smallholder agriculture and empowering women. On the matter of population control he drew applause for saying “nothing affects fertility more than educating girls,” an area MEDA takes seriously in its efforts to empower women.

Photo by Steve Sugrim

Saturday keynoter David Haskell,

With three Mennonite colleges nearby, the convention had plenty of musical

CEO of Dreams InDeed, an organization input like the Bethel College Jazz Ensemble (pictured). that seeks to strengthen social entrepreneurs in difficult regions, urged his audience to “dream of synergy” to leverage greater impact. He illustrated principles from his research and experience that unlocked the power of networks to weave collective impact.

“What is your dream?” he asked his audience. “Why did God put you on this planet?”

Haskell said his litmus test for a worthy shared dream included questions like, “Do the poor see the dream as good news? Does the dream invite all to participate and require all to change? Is the dream worth bleeding for?”

He pointedly posed a dream question to MEDA as it celebrated its 60th anniversary: “What’s the dream for MEDA for the 70th? What’s the dream for your business?”

Sunday’s worship speaker was Marion Good, regional director of resource development in MEDA’s Waterloo office. She told inspirational stories from her own life and from her MEDA travels of overcoming obstacles on the path to hope. More than 30 seminars explored various aspects of professional development, business and MEDA-related topics.

A pre-convention seminar on “Sustaining Your Family Business,” with family business specialist Lance Woodbury and attorney Timothy Moll, addressed succession, balance, legacies and working through conflict to bring about healthy change. “Where are you headed in 10 years,” Woodbury asked the family business owners in attendance. Were the right structures and ownership plans in place? Were family members playing to their strengths or working against the grain? Were performance expectations clear for both family members and employees? Did people know where they stand? Other seminars tackled topics such as What Matters to Your Employees; Building Leadership Opportunities for Women; Keys to Sales Success; What Boards and Board Members Need to Know; The Entrepreneurial Spirit of Orie O. Miller; and Making the Internet Work for You. Local tours visited businesses like Excel Industries, Learjet, Harper Industries, Belite Aircraft, Jako Farm, Mennonite Press and Flint Hills Design, and attractions such as an underground salt museum, historic Wichita, Cosmosphere and Space Center and Kauffman Museum. Musical input was strong from area Mennonite colleges and artists. The convention heard from the Sunflower Trio, the Hesston College Bel Canto singers, the Bethel College Jazz Ensemble and the Tabor College Concert Choir. The next MEDA convention will be held Nov. 6-9 in Winnipeg with the theme “Human Dignity through Entrepreneurship.” ◆

By the numbers

What a difference a decade makes

Excerpts from president Allan Sauder’s “state of MEDA” message to the Annual General Meeting:

I’m going to take a bit of a risk. People say one thing that keeps our AGM from being boring is that we tell lots of stories from our work and don’t spend all of our time hashing through numbers. Well, I happen to enjoy numbers, and I think they are an important part of our story. I’m not going to take you back to the beginning of MEDA 60 years ago, but rather to 2003 when we celebrated our 50th anniversary at the convention in Winnipeg. I am going to look at where we were then and where we are today, 10 years later, by answering 10 frequently asked questions with some numbers. 1. Where does MEDA work? In 2003 we listed 25 countries where MEDA was engaged. Today, that number has doubled to 49, from Afghanistan to Zambia. Among these, MEDA had projects and/or direct investments in 21, another 20 received indirect investments through one of the funds with which we are invested, and eight received consulting services only.

2. How do we decide where we will work?

That answer involves a four-legged stool of questions. The first leg we look at: Is there a need? It can be argued that every society has poor people who might benefit from MEDA’s work, but the reality is that we don’t work in higher-income countries, like Japan. The second leg: Does the need fit one of our core competencies? We won’t be effective if we lose our focus on what we do best. The third leg: Can we find key local partners who have the competence, with support from MEDA, to deliver specific aspects of the project and, most importantly, to carry on the work beyond the life of the project? And the final very important leg: Can we find matching funds from an institutional donor to multiply the funding that our private supporters provide? This year, we were able to multiply every donated dollar

Like yeast in bread, seed capital from six decades ago is still leavening

by a factor of 6.8 with government and foundation fundnew impact ing. In 2003, that factor was 4.6. 3. How many staff does MEDA employ? The past decade has seen our staff grow from 120 to 318, including 61 positions based in our four North American offices, 242 in our overseas offices, and 15 interns. Working through local partners has helped us keep our staff growth small compared to other growth indicators. 4. How big is the Sarona Risk Capital Fund? In 2003, we listed total assets in the fund of $5.4 million. Today assets stand at $20 million, an increase of 3.7 times. But that’s only the beginning of the story. This seed capital fund, which includes 1953 dollars repaid from that first

Photo by Steve Sugrim

President Allan Sauder at the AGM: “I happen to enjoy numbers.”

Photo by Dave Warren

Extending the reach: MEDA’s numbers don’t even count the 117 people employed by this Nicaraguan chile farmer during peak season.

MEDA investment in Paraguay 60 years ago, is truly the leaven in the bread — the initial risk capital that multiplies in impact many times over.

Our 2003 annual report described our investment in creating MicroVest, “a new investment fund partnership that aims to raise $20 million of private capital to invest in profitable microfinance institutions around the Like yeast in world.” Well, 10 years later MicroVest has assets under bread, seed management of over $200 million! capital from six The year 2003 also saw us increase our investment decades ago is with MEDA Paraguay in CodipSA, a manioc starch still leavening processing company, as they prepared to open their secnew impact ond factory. Ten years later, four factories are in production, providing more than 8,000 small farmers with a reliable market for their manioc, supplying over 75% of the Paraguayan starch market as well as being the largest South American exporter of starch, serving countries around the globe. Our investment of $422,000 has been more than repaid through dividends and sale of shares, and the value of remaining Sarona shares sits at $1.8 million. 5. How many partners does MEDA have? In 2003, we listed 50; today that number has grown to 223 — an increase of 4.5 times. I already mentioned our partners’ importance in multiplying the impact of our staff and carrying on with the work. More important, they are based in the communities where we work. They know what’s going on and how best to respond. They are our best ally to ensure that staff remain safe in the often volatile situations where we work. And, they are key to building trust with and among clients. 6. How much private funding do you get? This year we were grateful to receive almost $6 million in private contributions from our supporters in the U.S., Canada and Europe. This is an increase of 4.6 times since 2003 when our private funding totaled $1.3 million.

7. What accounts for MEDA’s considerable

growth in revenue? In 2003 our total revenue was only $6 million; this past year it was $41 million, a growth of 6.8 times. Although our revenue tends to fluctuate year-on-year based on the types and cycles of projects we undertake, the overall trend has been one of significant growth. Three factors have been important: (a) The quality of our work and our increased ability to measure the impact of projects has given us a strong reputation with institutional donors. We now have a well-diversified base of support from the Canadian, U.S. and British governments, as well as from The MasterCard Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and an exciting new project in Yemen funded by the

European Commission. (b) Institutional donors are interested in scale, and MEDA has been able to scale up our interventions to reach millions of families. For instance, in Tanzania, where we have been working for the past decade to build supply channels for insecticide treated mosquito nets, more than 35 million nets have been distributed; the proportion of children under five sleeping under a net has increased from just 16 percent to over 73 percent; the under-five mortality rate has dropped by 28%; and 200,000 lives have been saved. That’s the kind of impact that donors, and indeed taxpayers want to see. (c) Finally, our work in engaging the private sector in development — a course set for us 60 years ago by none other than Orie Miller, a businessman and head of Mennonite Central Committee — is of great interest to governments today. Governments recognize that true sustainability depends on engaging local and international markets for the benefit of the poor. 8. It seems your projects are getting larger. Where a $3 million project was once our outer limit, we now have projects 10 times that size. In 2003, we had a total of $22 million of active contracts; today it’s $175 million, a growth of eight times. Keeping our pipeline of contracts full is a constant challenge. The time between submitting a proposal to getting all approvals in place can run several years. In the meantime, donor priorities can and do change. We remain closely in touch with our institutional donors and strive to ensure compliance with increasingly complex contractual terms and audit requirements.

9. Please explain “assets under management.”

Our annual report shows we had $340 million assets under management this year, an increase of more than 43 times since 2003, when we had less than $8 million. This total includes a series of burgeoning investment activities (Sarona, MicroVest, MiCredito) that support a range of micro, small and medium-sized businesses. Sarona Asset Management (SAM), a separate company we set up a couple years ago, manages our many investments and creates investment vehicles to attract and invest capital in emerging markets for the benefit of the poor. MEDA’s own Sarona Risk Capital Fund (SRCF) is invested in 118 companies (from microfinance to agriculture) that employ 164,000 people and serve more than 38 million low-income clients. (For more on the new frontiers of impact investing led by Sarona funds, see the following article by Gerhard Pries.) 10. How many clients do you reach? That’s our most important number, and it has by far grown the most. In 2003, we reached an estimated 250,000 clients; this year that number was 42 million — a multiple of 170 times!

Not all were helped in the same way. Through our Sarona fund investments over 38 million households at the bottom of the pyramid now have increased access to financial services, jobs and other products that make a real difference in their lives. And 3.1 million farmers and Like yeast in entrepreneurs are earning better incomes (often double or triple what they earned bread, seed before) through training, access to markets and financial capital from six services provided by MEDA’s partners. Some 1.7 million decades ago is more homes in rural Tanzania now have mosquito nets still leavening and better health. And those numbers don’t even count new impact the clients of organizations we worked with in the past who continue to receive services from our local partners long after MEDA is no longer involved.

In September, I visited clients of our TechnoLinks project in Nicaragua. One farmer, Eddy Sandoval, is a contract grower for one of our partner companies, Chiles de Nicaragua, which buys chiles from 170 farmers like Sandoval and ships chile paste to the McIlhenny Tabasco Co. in the U.S. Sandoval proudly showed us a video he had made about the chile growing process, and how he had learned to apply drip irrigation to his seven-acre plot. He said he made about $8,000 to $12,000 profit every year from his chiles — a significant amount for this poor farm family. Most impressively, during the three-month growing season he employed 117 people from his community. These are impact numbers that our estimates of client reach don’t even begin to count.

Obviously, numbers are not the only measure of our success, but to businesspeople they mean something. For me, they are an important part of honoring our vision — that all people may experience God’s love and unleash their potential to earn a livelihood. ◆

Sold!

Spirited auction raises $86,000 for new MEDA project in Ghana

Who, other than the most die-hard fan, would shell out $8,500 to watch the Detroit Red Wings play hockey?

Or pay $15,000 for a pair of brass bookends fashioned by beloved MEDA stalwart Erwin Steinmann?

It was all part of the Friday evening highjinks as MEDA celebrated its 60th anniversary with a celebratory fund-raising auction. Former board member Paul Tiessen, a professional auctioneer, entertained the crowd with hilarity and antics while eliciting topdollar bids to support a new MEDA project in Ghana.

Tiessen himself arranged one of the most popular items — a hockey package of four tickets to see the Detroit Red Wings play the Chicago Blackhawks on Jan. 22 — through his friendship with Red Wings coach Mike Babcock, his summer cottage neighbor in Saskatchewan.

The tickets are Babcock’s family seats, and come with an opportunity to watch both teams practice that morning, plus a postgame dressing room visit to meet players and coaches, and an autographed jersey of Red Wings captain Henrick Zetterberg.

Bidding was lively and brought a total of $8,500 through a joint purchase by Red Wings fan David Seyler, New Hamburg, Ont., and Blackhawks enthusiast Pat Vendrely, Flossmoor, Ill. The two friends plan to attend together but “their wives will sit between them during the game,” says Carol EbyGood, convention planner.

Ron Schlegel, Ayr, Ont., was the high bidder for a pair of distinctive brass bookends celebrating the 60-year anniversary. They were designed by longtime MEDA member Ervin Steinmann, co-founder of Riverside Brass & Aluminum Foundry in New Hamburg. Riverside Brass did the rough machining and

MEDA staffer Meghan Denega displays brass bookends crafted by longtime MEDA member Ervin Steinmann.

Ron Schlegel is presented with commemorative bookends which he got for a bid of $13,000, then good-naturedly upped it to $15,000.

Spotter Bob Kroeker (standing at left) checks signals with Curt Dorsing, who went home with an original painting by Marketplace designer Ray Dirks.

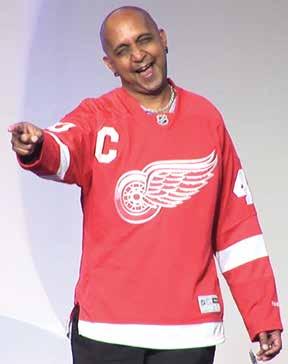

MEDA’s multimedia designer Steve Sugrim models an autographed jersey of Red Wings captain Henrick Zetterberg.

Hockey fans David Seyler and Pat Vendrely joined forces to win the bid for a hockey package featuring the Detroit Red Wings and the Chicago Blackhawks.

engraving, and Steinmann himself did the polishing and finishing.

Schlegel, who made the final bid of $13,000, later mentioned that he would have been willing to bid even higher for the one-of-a-kind set. Word got back to a MEDA staff member who invited him to pay more after the fact, which he did, upping his bid to $15,000. Other auction items included various tours, vacation packages and football tickets, a rare Sauder Woodworking tractor-trailer replica signed by the late Erie Sauder, one of MEDA’s founders, as well as fruit baskets, original paintings and quilts. A silent auction featured items ranging from furniture to artwork.

The auction raised $86,000 for MEDA’s new GROW project, which helps women in Ghana improve nutrition, income and soil fertility by growing soybeans. ◆

Caring enough to invest

MEDA pioneered the idea that private capital can produce both profit and social benefits. The financial world has since taken note.

Gerhard Pries is managing partner of Sarona Asset Management, a company set up by MEDA to invest for the benefit of the poor. His comments to the Annual General Meeting:

company that gathered shareholder capital here to invest in the Sarona Dairies in South America to produce both profit and social benefit. Ahalf-dozen years ago I stood in front of you declaring that the world needed less aid and Sixty years ago it was unheard of to use private capital to achieve development more investment, less charity and results. But it worked, more capitalism. then as now.

Friends who knew me as a Today, as a child of centrist, or possibly even cen- MEDA, Sarona Asset tre-left, thought I must have been Management Inc. carserved some Ayn Rand kool-aid, ries out that element of or was sleeping with a copy of MEDA’s mission: creatAtlas Shrugged under my pillow. ing business solutions to

I was also roundly chastised poverty by investing in for casting aspersions on the good work of certain chari- private business, by infusing companies with progressive table institutions, which of course was not my intent as I business strategies, and by caring about companies’ social had actually been referring primarily to bi-lateral aid. and environmental outcomes.

We all knew, I argued, that throughout recorded hu- In the mid-90s we began building investment funds so man history there hadn’t been a single case of sustained private individuals could invest with us. Between our Mipoverty reduction without growth in that economy. We croVest and Sarona funds, we now manage $340 million all knew that, if people had a way to earn a living, they’d of investment capital, feed their families and build healthy communities. seeking to deliver at-

Yet for over 60 years, the world had focused on build- tractive financial returns ing latrines, digging wells and generally pushing gelatin to our investors while uphill. Trillions of dollars of aid had been ploughed into building up companies developing countries with negligible impact on poverty. and communities where

Finally Africans had risen up, declaring, “Your aid is we invest. killing us! Keep it out of our continent. Instead, believe in We may be at an us! Invest in our people; invest in our businesses.” inflection point, where

We hear you, Africa. MEDA heard you 60 years ago. investing in developing countries is now a beSixty years ago MEDA was created as a private lievable strategy; where investment company — a tax-paying private investment we will begin to chan-

Hearing the call to invest: Gerhard Pries addresses the AGM Our investments build companies by infusing them with solid social and environmental values.

nel not thousands, not millions, but — dare we believe — even billions of dollars of capital to developing countries.

It wasn’t always so. Thirteen years ago, The Economist declared Africa a lost continent. Thirteen years ago, when we spoke to investors about investing in Africa, Asia and Latin America, we were turned away at the door. Sure, they had interest. Sure, it was intriguing. But my, what risk that must entail! “Do you really think we won’t lose it all?”

Today, The Economist has changed its tune, and so have our investors.

Today our investor capital flows to agro-processing companies such as Khyati Foods Ltd. in India, a private company that supports 10,000 smallholder farm families by processing their organic cotton and soybeans for

Goshen students win ... again

In 2000, The Economist had a dim view of Africa’s prospects (left). By 2011, their opinion had changed.

Goshen College business students won first place at the Student Case Competition during MEDA’s annual convention in Wichita.

This was the second year in a row that Goshen won the MEDA convention’s annual competition for college and university students enrolled in a business-related program.

Teams from six schools were invited to develop a business plan for Prairie Harvest, a local foods market in Newton, Kan. Teams had several weeks to research the company and prepare a solution to one of its challenges.

During the case presentation, the teams offered a business plan to the judging panel, made up of MEDA staff and Prairie Harvest owners Becky Nickel and Carrie Van Sickle.

“The way the GC team incorporated our overall store mission — local, healthful foods in a community-minded business, with the novelty of peppernuts — was impressive,” Nickel said.

The first round of judging determined Goshen College and Tabor College, Hillsboro, Kan., as the two finalists, with Goshen gaining top spot in the second round. Other schools were Bluffton (Ohio) University, Canadian Mennonite University, Winnipeg, Conrad Grebel University, Waterloo, Ont., and Eastern Mennonite University, Harrisonburg, Va.

Goshen’s team was composed of Niles Graber Miller, a senior business major from Goshen; Karli Graybill, a senior accounting major from Goshen; Luis Lopez, a senior accounting major from Asuncion, Paraguay; and Josh Stiffney, a senior accounting major from Goshen.

As part of its research, the team visited a local business back home with a similar business plan and market.

“To have advice from a real business experience gave us credibility and helped us see the solutions with real scenarios and achievable goals,” said team member Lopez.

“The GC team had exactly the right approach, which was to get out of the classroom and learn from a real business,” said Michelle Horning, Goshen’s professor of accounting. ◆ export to Europe and America. We like Khyati because it is profitable, because it is environmental, and because it is social.

We invest in private companies in developing countries: • small to mid-market companies with an enterprise value of $1-150 million; • companies that need growth equity; • companies that need professional management to help them achieve world-class standards of excellence.

And with each investment, whether in an agro-processing company, a micro-finance bank, a technology company or a consumer goods company, we seek to build up companies and communities by infusing them with progressive social and environmental values.

Today, such investments attract $340 million into our funds. What started with MEDA members, is now attracting capital from pension funds, university endowment funds and family investors from around the world. The mustard seed is growing.

And so I’ll repeat what I said a half-dozen years ago: • When capital is invested with care and positive intent, business can be a force for positive social development. • With formal regulation and social intent, business can bring hope and peace to poor communities around the globe.

Slowly but surely this world is becoming a better place. Let’s keep leading that change. ◆

Lessons from the goats

They were a nuisance, wandering freely through the villages. It made sense to fence them in. Or so he thought.

by Merrill Ewert

The ink was barely dry on my Tabor College diploma when I first arrived in Southern Zaire (now Congo) to manage a feeding program for tuberculosis patients at a Mennonite Brethren mission hospital. With a grant from a European funding agency, I was also encouraged to help local villagers address the agricultural problems of the region.

One of the first things I noticed was the goats that roamed freely through the villages. Thin, smelly and covered with flies, they nonetheless wandered in and out of houses, defecated in the compounds, ate cassava (people’s staple food) from the drying racks, rummaged through the garbage and nibbled at the laundry drying in the sun. The goats destroyed gardens in the community protected by small, stick fences that were easily breached. I saw families become angry with each other when the animals of one ate the vegetables of the other. At best, these goats were a health hazard and a general nuisance.

Raised on a Minnesota farm, I had won awards for my pedigreed sheep. I understood the basic principles of animal husbandry. This experience combined with my anthropology courses at Tabor led me to conclude that there must be a better way to raise goats in Zaire.

After discussions with several local farmers, I ordered 50 rolls of wire from the United States which would be used to fence in farmers’ goats. By fencing in the goats, I reasoned, the people would be rid of several problems. They would also improve the nutrition of their animals who would graze on better grass in pastures outside the village. Farmers could monitor their animals inside the fence and augment their diets with millet, corn and grass. I saw a potential breakthrough in goat production in the community through the introduction of this new technology.

Meanwhile, political problems flared up in

Zaire. Mail was lost and messages went undelivered. For reasons unknown, my order for 50 rolls of wire never arrived at its destination. The wire was never shipped and the goats continued to wreak havoc in the community.

I discovered, however, that most farmers could not have afforded to purchase rolls of wire from me. Through observation and experience, I also learned more about goats. 1. God feeds the goats. Farmers may be responsible for feeding their families but God feeds the goats. A goat raised inside a fence, I learned, will surely go hungry. They are expected to scavenge. To help villagers achieve a better life, I had proposed a solution through which the goats would probably have starved to death. 2. Goats eat garbage. Though goats snatch cassava from the drying racks, they also eat garbage, drink rain

water from tin cans lying in the village and drain puddles which attract mosquitoes. I had said, in effect, “I have a great idea to help improve your lives – banish your garbage disposal systems from the village!” 3. Grass draws mosquitoes. The Anopheles mosquito which carries malaria is responsible for more deaths than any other living creature in the world. Goats destroy grass by tearing it off at the roots. Left to themselves, they will strip a village of grass thereby making it a less desireable habitat for mosquitoes. These indigenous lawn mowers that I tried to remove from the community help reduce malaria by controlling the grass. 4. Snakes dislike bare ground. A grassy compound is an invitation to snakes to join you at home. With a little help from their goats, villagers keep the ground bare around their houses, effectively discouraging these visits. If a snake slithers into the compound in spite of this precaution, you can usually find it by following its tracks in the dust. My proposal for improving goat production in the community implied removing its snake control system. 5. It’s cold at 3,000 feet. Grass walls are poor insulation against cold weather. However, goats inside your house will keep you warm. By trying to confine animals to fences outside the village, I was guaranteeing that people would be cold at night when dry season winds chilled the community. 6. Goats hear thieves. Some goats sleep inside the houses while other farmers build lean-to shelters under the eaves. People told of being awakened at night by the bleating of goats when thieves sneaked into their compounds. My suggestion for solving the community’s goat problem was to keep nature’s burglar alarms outside the village. There, they would be of no assistance, and would probably even be stolen themselves. 7. Lions eat goats. One family tied its goat to a tree inside the compound and woke in the morning to find only the leash remaining. Tracks in the dust revealed that a lion had stopped by for a midnight snack. Goats that sleep in your house, however, are reasonably safe. My plan for a goat pasture outside the village would have been tantamount to opening a cafeteria for the lions and leopards of Southern Zaire. 8. A sick goat is a dead goat. When you sleep with your goat, you usually notice when it’s ill. If animals sleep outside the village, they may become sick and die before you notice. An apparently sensible solution for raising goats had the potential for economic disaster should health problems enter a particular herd. 9. Every goat in Africa has worms. Goats raised in restricted areas have higher rates of infestation by internal parasites and are more susceptible to its consequences. Though I did not understand the physiological principles involved, I observed that health problems quickly spread throughout a herd when goats are raised in restricted quarters. However well-motivated, my proposal for improved animal husbandry practices had yet another fatal flaw.

He had unwittingly planned to get rid of their indigenous lawn mowers that help keep malaria at bay

The goats of Southern Zaire taught me some

important lessons. First, farmers know more about their problems than we development workers usually realize. At the same time, we understand much less than we think we do. Generally, things are not what they seem to be. Urgent human needs often compel development workers to take immediate action. We draw on our training as we interpret the problems of development and reflect our own experience as we suggest possible solutions. Not surprisingly, this can lead to big mistakes.

Second, the process of development takes much longer than we imagine. Introducing new solutions before we understand the problems they are designed to solve is a serious but common mistake. It took me years to learn what Zairian farmers have always known. Short-term workers should be more modest in making development decisions.

Third, real understanding comes through relationships. I tested my goat fence proposal on various farmers who all agreed that it was a brilliant answer to a pressing local problem. Thus convinced of its viability, I moved ahead, believing “this is what the people want.” Much later, I learned that my friends had carefully told me exactly what they thought I wanted to hear. They did not want me “lose face” or feel badly by disagreeing with my proposal. Some also felt that I might have some inside information that superseded what everyone had known for generations, that you cannot raise goats inside fences under those conditions. Only after I had established deeper, personal relationships with several individuals did I begin to understand some of the deeper problems of the community. Only then were people willing to point out the flaws and weaknesses in my suggestions.

Development is a process of growth through which people progressively become more aware of their own problems and committed to finding appropriate solutions. We can facilitate that process, provide technical information and encourage them in this quest for a better life. We must, however, be modest in proposing solutions to problems we may not understand. That understanding comes not as a result of our technical competence but through the personal relationships of trust with those whom we want to serve. ◆

Merrill Ewert was president of Fresno Pacific University from 2002 to 2012 and now carries the designation President Emeritus. He earlier worked at Cornell University and Wheaton College and spent many years in development work, including stints with Mennonite Central Committee and Medical Assistance Programs. His article first appeared in this magazine in May/June 1987.