39 minute read

Soul enterprise

Giving God the business

Forty years ago you had to search hard to read about Christian faith in business. Books on the topic were scarce, unlike today when you can find thousands.

One gem of the times was God Owns My Business by Stanley Tam, which caught the imagination of a whole generation of Christian entrepreneurs when it was published in 1969. It told the story of an Ohio businessman who started a company (silver reclaiming first, then plastics) and after a few years decided to give God control with 51 percent of the company. It took a bit of legal footwork to pull it off, but eventually it worked, and from that point on Tam was an employee and minority shareholder.

Eventually Tam turned over the remaining 49 percent, making God the sole owner of the entire company. Tam was paid a salary, and profits were sent to Christian charities.

Early readers may have wondered what happened to Stanley Tam. It turns out that at the age of 94 he is still involved in the company that he turned over to God.

The company has 90 employees and ships out $40 million worth of plastic goods a year to customers around the world. Profits still fund various kinds of Christian outreach; officials say tens of millions of dollars have flowed into missionary enterprises over the years. (Marketplace Ministries)

Why don’t we pray for business?

I’ve been participating in church worship services for 50 years. I’ve heard or offered thousands of prayers in the context of congregational worship. Yet I cannot remember either hearing or offering a prayer that focused on — or even mentioned — business. In my pastoral prayers I would regularly intercede on behalf of government officials, teachers, police officers, firefighters, parents, grandparents, pastors, churches and mission partners. But I cannot remember offering prayers for bankers, lawyers, realtors or salespeople. Nor can I recall praying for business institutions: banks, law firms, corporations, small business, brokerage firms, etc. This seems especially odd to me now, given that the majority of working people in my church were in business settings such as those I just mentioned. Why didn’t I pray for them in the activity that took up so much of their time and meant so much to their lives? Why didn’t I pray for the companies they worked for or, in many cases, owned?

I believe this is the norm for Christians, both in their private lives and especially in their corporate worship. Now, I’m sure that individuals pray about their own businesses and jobs. And I would sometimes pray for people’s jobs when they came to seek my pastoral advice about situations they faced in their work life. But for some peculiar reason these private prayers did not impact my public leadership of prayer in worship.

If pastors and others who pray in worship services began on a fairly regular basis to pray for businesses and business leaders, for bosses and employees, for church members in their professional roles, that example would have a powerful impact on the prayer practices of the congregation, both in corporate and private prayer. — Mark D. Roberts in Faith in the Workplace newsletter

A river runs through it

Does faith make a difference?

Can religious faith make business better at creating prosperity around the world? Does faith improve a firm’s relationship with key stakeholders (customers, owners, workers, future generations)? Are faith-based and faith-inspired enterprise solutions to poverty more effective than conventional methods?

If you can document a good answer to these questions, here’s an essay contest just for you.

The competition is sponsored by two organizations committed to strengthening enterprise-based solutions to poverty that are faith-based and faith-inspired — The SEVEN Fund and the Center For Interfaith Action on Global Poverty (CIFA).

Top prize: $5,000. Submission deadline: Oct. 15, 2010.

Making genius work

Are you a brilliant artist ... or are you someone who can walk alongside and help translate that brilliance into something that works? When God sends us an artistic genius, someone else who “gets it” is usually part of the package, says screenwriter Barbara Nicolosi. “Vincent Van Gogh had his brother, Theo. Emily Dickenson had her sister-in-law, Susan Gilbert. The Beatles had Brian Epstein.” The ability to understand the brilliance of an artist is itself a vocation, she contends. “There are two kinds of people in the world: people who are artists and people who are supposed to support them. Figure out which you are and do it with vigor.” (Quoted in Christian Century) Young people looking for a career to change the world need go no farther than the kitchen sink to turn on the tap and watch the water flow.

Few global issues embrace more of humanity’s prospects than water — a scarce resource that is growing scarcer.

There is no shortage of astute public commentary on the state of water, perhaps the most recent being a special report in The Economist titled “For want of a drink.” In its usual crisp fashion, the magazine explores myriad dimensions of this resource, from food security to disease to petroleum production, not to mention the unfolding apocalypse in the Gulf of Mexico. For much of the world, water is a human right — “a necessity more basic than bread or a roof over the head.” It can dominate and destroy lives, especially among the billion people who go to bed hungry every night, partly for lack of water to grow food.

“It has provided not just life and food but a means of transport, a way of keeping clean, a mechanism for removing sewage, a home for fish and other animals, a medium with which to cook, in which to swim, on which to skate and sail, a thing of beauty to provide inspiration, to gaze upon and to enjoy,” the magazine observes.

Water could be the most expansive cross-cutting issue of our century. Anyone entering a career in engineering, agriculture, industry, economics, law, medicine, accounting, politics or peacemaking, to name a few, could conceivably use their skill-set in the battle to protect this resource.

Overheard:

“I’d rather fail at something new than succeed at something old.” — Ben Cohen, co-founder, Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream

Microfinance interest: How much is too much?

Lenders feel tarnished by critical news reports

Microcredit clients along the rocky slopes of western Haiti never heard any loud vroomvroom when Edvy Durandice came calling. All they’d hear was the braying of a mule.

While other credit officers traveled on two wheels, Edvy relied on four hooves to navigate the twisting paths to where his clients lived. He became a top performer in MEDA’s village bank program.

Loan officers can spend a lot of time visiting clients who depend on them for financial counsel and mentoring. Anyone riding along would see why microfinance can cost three percent a month.

“The world of microcredit is a far cry from the loan department of your local bank,” says Julie Redfern, MEDA’s vice-president of financial services.

Which is why many microfinance institutions (MFIs) feel unfairly accused by recent debates over the interest rates they charge. Media reports have alleged that a few MFIs have earned huge profits by charging whopping interest rates. That’s not the experience of most microcredit agencies, many of whom struggle just to stay in the black, but the broad brush of headlines has stained many who don’t deserve it.

MEDA has been involved in microfinance for 35 years, even before Muhammad Yunus put the industry on the map by launching the Grameen Bank in 1976. From the start, microfinance was touted not as “cheap credit” but rather as “affordable credit.” But “affordable” means different things in different places. In Canada, for example, credit card rates can be at least 20 percent. “People don’t seem to have a problem with that,” says Redfern. “In the developing world, bank credit card rates are often comparable to MFI rates.”

Microcredit interest rates have never been as low as what Canadians and Americans can obtain from their local bank, but for the loan-starved global poor, the rates have always been spectacularly below their other alternative — the ever-present loan sharks who charge 200 or 300 percent.

Rates vary depending on context and country. Comparing them with Canada and the U.S. is like comparing apples and potatoes, as microloan rates have to take into account other variables like high inflation, lack of collateral and shorter repayment schedules.

Many microfinance institutions charge an annual interest rate of 20 to 36 percent (which Redfern calls “very reasonable”) while some charge 35 to 60 percent, still well below the rates some news articles have targeted. “This reflects the high costs of administering many thousands of small loans and a more personal level of relationship with clients in a high-risk market,” she says. “It sometimes includes technical assistance such as basic business skills training and support.”

Then, too, regional factors like wages can jack up rates. “In countries where labor costs are really low — like India and Bangladesh — MFI rates are correspondingly low,” says Redfern. “In other countries, like Jamaica, wages are high, and rates are, too. In poor countries where there are loads of NGOs we see upward pressure on wages, especially when there is a shortage of skilled labor, as in Haiti.”

The high risk of microfinance relates more to the stability of the country and the currency in which the MFI operates than the risk of default on loans by clients, she adds. Most clients are eager to repay their loans, because they know they will need credit again in the future to grow their businesses.

From just about every angle, microcredit

loans to the poor cost more to provide. In Nicaragua, for example, it can cost one percent just to maintain the system, so charging three percent a month is not unreasonable, especially when you add “forgiveness” factors

such as going easy on small farmers who can’t pay until after harvest.

When MEDA lent money to bean farmers in Nicaragua, its penalty for late payment was two-thirds of one percent, far below the 3.5 percent or more charged by other lenders. “We don’t ding them as hard if they fall behind,” a staffer explained. “Nor do we ask for payments to start until harvest is over. These considerations all cost us something.”

While a rate of 36 percent may sound high in Canada and the U.S., it’s not as high as it seems when you consider that the term is much Well-meaning shorter (often less than a year) and many small agencies do no businesses can easily recoup their investment several times over durfavors if they ing the span of the loan. “When you lend underprice $75 it costs you just as much in overhead themselves and — the bookkeeping and other office mainthen go out of tenance — as though you’d lent $5,000,” business, leaving write Jim Klobuchar and Susan Cornell clients in the lurch Wilkes in The Miracles of Barefoot Capitalism. “In microcredit the key to successful lending is the diligence and the good will of the loan officer, who tracks every client as often as once a week, to keep current with the client’s needs, health, and performance. So the disparity in cost of loan maintenance is even more lopsided.”

And those additional costs need to be recovered in order to keep the program sustainable so there is money to lend to the clients of tomorrow.

Sustainability is the mantra of MFIs and other

effective development programs. Well-meaning agencies do no favors if they underprice themselves and then go out of business, leaving clients in the lurch.

“The best thing you can do for the poor is stay in business,” says Gil Crawford, head of MicroVest, the investment firm founded by MEDA and CARE to provide capital to MFIs.

A similar note is sounded by Eric Thurman, former CEO of Opportunity International and HOPE International. “I have learned that programs applying artificially low rates usually fail because interest discounts are used to prop up weak businesses that should, instead, be allowed to close,” he writes in A Billion Bootstraps: Microcredit, Barefoot Banking, and the Business Solution for Ending Poverty. “What poor people need are authentic, durable sources of income.”

In Thurman’s experience, “when microcredit programs err with interest rates, it is not by charging too much, but rather too little, failing to cover the real costs of delivering their services.... Microcredit organizations must be self-sustaining, able to absorb operating costs, the few bad debts, and currency fluctuations. Otherwise, the only way to cover the shortfall is to take money out of the loan pool. Decapitalizing the loan portfolio will cause the program to stall and eventually fail.”

That said, a few financial institutions have been getting away with charging usurious rates. The New York Times recently reported that Te Creemos, a Mexican lender, charges an annual average rate of 125 percent, giving it the dubious distinction of having some of the highest interest rates and fees in the world of microfinance. The average rate in Mexico is said to be around 70 percent, double the global average.

The article mentioned another Mexican firm, Compartamos, which charges an average of over 80 percent in interest and fees. More troubling than the actual rate was that the MFI, as the largest in the region, was pushing up interest rates across the country.

The Times noted that “most microlenders are honest, with experts putting the number of dubious institutions anywhere from less than 1 percent to more than 10 percent. Part of the problem, however, is that all kinds of institutions making loans plaster them with the ‘microfinance’ label because of its do-good reputation.”

MicroVest’s Crawford says robust, commercial microfinance is one of the best ways to lift the working poor permanently out of poverty.

“There is strong evidence that commercial microfinance leads to rapid scaling, innovative new services and lower costs to borrowers,” he says. “From Bolivia to Mongolia, in market after market, MicroVest has witnessed that commercial competition triggers a steep drop in interest rates, an expansion of geographic outreach and the introduction of higher quality, more diverse financial services. More importantly, commercial microfinance also contributes to a deepening of financial markets, which the Asian Development Bank has shown to correlate with substantial economic development.”

Redfern believes that overall, the poor are well served by the institutions providing microcredit.

“In any business environment, you can find plenty of opportunists if you choose to look for them,” she says. “Finding an example of an MFI charging extremely high rates and then using it to broadly characterize the whole industry is negligent. I contend that most MFIs are very sensitive to the issue and don’t want to pass on inefficiencies to the poor. Most do their best to balance their business goals and social goals: they have to be profitable and yet improve the lives of the poor. Most MFIs in the world still struggle with profitability and are not making obscene returns, as some news articles have alleged.” ◆

Potholes on the pilgrim path

The pot of gold was full, yet empty. He found there was more to life. Like integrity.

William Martens has an extensive track record as an entrepreneur, notably as owner of several very popular Tim Hortons coffee shop franchises, and as head of Marwest, a leading real estate management firm in Canada and the U.S. Along the way he also spent 14 years as a pastor. Martens recently spoke to the Winnipeg MEDA chapter about his pilgrimage in business and faith. Following is a condensed version of his talk.

Iwas one of nine children growing up in an impoverished immigrant family from South America. As a child, I remember watching my Mother chase a bill collector from the porch with a broom. That left an indelible imprint on my mind.

I purposed in my heart never to be poor and suffer as my parents had. And so I was driven by a materialistic desire to succeed. I believed that financial success would make life perfect. I set a goal to become a millionaire by the age of 28, and reached it a year early.

One morning I came into work and my secretary looked at me and said, “We’ve got to talk.” My experience taught me that either meant “I want a raise,” or “I’m quitting.” To my surprise she looked me in the eyes and said, “For a man who has everything you look like you could jump off the Disraeli Bridge.” Those words stopped me in my tracks because in my heart of hearts they rang true.

I had come to believe that financial success would be my pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. But the truth was I had become a miserable angry young man and when I looked into the pot it was full of disappointments and broken relationships. • My co-workers suffered consequences if they got in the way of my goals. • My friends became virtually non-existent as I poured most of my time and energy into my work. • The relationship to my wife and children was a “Hello, how are you” and “What’s for dinner” because I was too preoccupied with business activities.

I remember calling home one night to let my wife, Erica, know I was going to be late for dinner and my oldest son answered the phone and didn’t even recognize my voice. I knew then I was in serious trouble.

But perhaps my greatest disappointment was that I had above all else sacrificed what little religious affiliation I had to God. The belief that financial success was all I needed had ultimately betrayed me. It was a very dark and depressing time in my life.

During this time I happened to meet a very poor immigrant, the kind of man I had promised myself I would never be. But he was a very happy poor man. He expressed a lot of joy in life — unlike me. And so I asked him, “How is it possible you can be so joyful and have nothing?” He told me something I had long forgotten — that God needed to be the center of my life, and not financial success. He reminded me that it is only through Jesus Christ, God’s son, that I could find true joy and happiness. And so I recommitted my life to Christ and began a renewed relationship with Him.

Let me pose a question: If people who knew you were asked for five words to describe you, would integrity be one of them?

Integrity is character related. Image without character always comes up short. It isn’t something you can just dress yourself up in and head to work in the morning. It has to become a main component of who you are as a person before God and people.

Integrity is about truth and honesty, saying what you mean and meaning what you say. It keeps voice and touch together, being sure that what you say is matched by what you do. And why is that important? It is so that we don’t live a lie. I cannot think of anything more damaging to the Christian witness than an individual who lives a spiritually schizophrenic life believing they can behave differently in their business world than at home or at church.

Here are some things integrity has come to mean for me in business.

My integrity should set an example to those I have been privileged to lead. “Be a good example to those around by modeling what is right and true,” says the Apostle Paul. “Why? So that you need not be ashamed of yourself” (Titus 2:7).

Leadership always involves modeling. This means you and I are being watched, from the way we dress to how we carry ourselves, to the way we behave. It also means that I carry my faith into the workplace by virtue of being a reflection of Christ.

When Erica and I began working as franchise operators for Tim Hortons we wanted to create a culture in our stores that reflected who we are as Christians. Our intent was to model honesty, trust and respect. Over time the staff began to realize that if they practiced these very same character-related principles, it made their work environment a safe and enjoyable place to be.

It wasn’t long before one of our regional vice-presidents commented that our stores appeared to be a direct reflection of the ownership group. This in turn gave us an opportunity to share the values and principles of life we hold dear. About a year later one of the VPs asked if I would give the opening prayer at the annual convention in Calgary.

At the corporate level I view modeling integrity more as a mentorship in getting prospective executives onto the right path. The truth is that more is caught than taught. Integrity means valuing people, recognizing that every human being has innate dignity. Genesis 1:27 says that God created us in His own image. This means we must actually respect and care about those who work for us and not view them as the enemy of competing interests. It took me a while to figure this out. I have seen many business leaders use employees to further their own selfish ends — taking credit for the hard work of others, or manipulating employee behavior to satisfy one’s own needs.

I used to have a secretary who had low self-esteem which expressed itself in her desire to work exceptionally hard in order to gain my approval for her efforts. Well, I’m not proud of it but there were times when I knowingly used her insecurities for my own selfish gain. Looking back, I realize how little I truly valued her. One of the obvious ways to express value to those under your leadership is a fair wage. At Marwest, we express our gratitude with bonuses, various benefits and stock options. Another way we express value is by encouraging staff to communicate ideas and suggestions about workrelated matters that will allow us to improve their environment. We also have a “whistleblower” One of several popular Tim Hortons policy that allows anyone within our group of franchises operated by the Martens companies to freely express any concerns or family in Winnipeg: “We wanted to abuses they might experience or witness. This create a culture in our stores that gives them a sense of ownership and responsibilreflected who we are as Christians.” ity to their working environment. It also speaks to valuing their opinions and thoughts. At Tim Hortons, how we value people takes on a slightly different shape. We can’t just increase wages because there are constraints placed on us as franchise operators within the quick service industry. However, we can offer affirmations, awards and scholarships that are an expression of value. Because wages tend to be minimum, we will often go beyond to help those who have made Tim Hortons their career choice when they may encounter personal hardship. It’s important to me that those under my leadership know they count. Talk is cheap, but to step into their lives in a meaningful way does more than words ever can. Whether they are working for $9 an hour or $90,000 a year, I want to value them as I would want to be valued, and more importantly, to realize that they deserve it because God values their lives. Someone once said that “Big ethical decisions in life don’t begin with trumpets blaring but with the small everyday choices and decisions we make.” At Tim Hortons we deal with huge amounts of cash. There are many ways not to account for some of it. How“I called home ever, I also know that had I started down that road there would be a pothole along the way that would swallow to say I’d be late me up. My sons who now own and operate the business reminded me not too long ago that they were watching for dinner. My me, wondering if at any time Dad would compromise his integrity. I am so thankful to God that I didn’t. son answered It was said of Daniel that in all the land there was no man like him, “no fault was found in him.” That’s a really and didn’t even big statement. It speaks of integrity. Here was a man who refused to compromise his belief system. recognize my God gives all of us the same courage and character to live out our lives in the same way. We just need to allow him sovereign control of our lives, and live confidently voice.” knowing that if we are willing, he is able. ◆

Helping Haiti’s homeless

Haitians left homeless by the January earthquake are getting housing help from a collaborative venture involving MEDA and Mennonite Central Committee.

MCC has agreed to contribute $1,430,000 to rebuild and repair hundreds of homes of impoverished microfinance clients, most of whom are women. MEDA will administer and monitor the 18-month project.

The women are clients of Fonkoze, Haiti’s leading microfinance provider. The agency serves 46,000 clients with microloans, as well as more than 200,000 microsavers. The earthquake destroyed a number of Fonkoze’s 41 branches throughout the country and took the lives of five staff.

In the weeks following the tragedy, Fonkoze’s credit agents met with all clients to inventory the losses they had suffered. Nearly three thousand clients reported not being able to stay in their houses due to destruction or severe damage.

“Most of Fonkoze’s clients cannot afford a loan to build a house,” says Julie Redfern, MEDA’s vice-president of financial services and a member of the Fonkoze board. “As a result, they will either totally decapitalize to invest in a decent house, or endure in substandard and unsafe shelter until they can, bit by bit in maybe 10 years, get back to the living conditions they had before the earthquake.”

Fonkoze is committed to addressing these client needs by repairing those homes that are still structurally sound and rebuilding those that can’t be repaired. It will accomplish this in five stages: • Set up a training center in the community of Fondwa to prepare community teams of masons and carpenters in techniques for building earthquake and hurricane resilient homes. • Build four model homes using those techniques. • Send the teams back to their communities to diagnose which houses can be repaired and which need rebuilding. • Repair and then inspect homes.

The project will enable Haitian families to live in decent housing that is rain, hurricane and earthquake resistant.

With a GDP per capita of only $525, Haiti is the poorest country in the western hemisphere. Nearly 80 percent of its population lives on less than $2 per day, and many of those, especially in the rural areas, on less than $1 a day. The vast majority have no access to financial services.

A crisis in housing

The earthquake claimed the lives of more than 250,000 people, and created 1.3 million Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) (more have been affected but not displaced). Housing was devastated. An estimated 105,000 houses were destroyed and more than 208,000 damaged.

The Haitian government is installing provisional shelters in some sites that will eventually become new permanent neighborhoods with permanent housing and sustainable infrastructures and basic services. In other camps, several initiatives aim to encourage refugees to return home, where possible.

The earthquake hit a population that was already very vulnerable: among Fonkoze’s clients there were many families who were not living in decent homes even before the earthquake. ◆

• Rebuild and inspect homes that can’t be repaired.

The joint MEDA/MCC project will contribute in all five stages. In addition to rebuilding/repairing homes for 775 families, MCC will also support training and monitoring of home construction/repair.

Between now and Nov. 30, 2011 the project aims to equip families with the technical and material resources they need to rebuild and repair their permanent houses so they are rain, hurricane and earthquake resistant. It will also train more than a thousand Haitian women and their adult family members in home ownership and maintenance.

“There’s also a considerable training spinoff for local builders,” says Redfern.

Local construction teams will be taught “Build Safer” techniques so the homes they build and repair will be as

Fonkoze — Haiti’s alternative bank

Fonkoze was founded in 1994 by a Haitian priest, Father Joseph Philippe. It has grown faster than any other MFI and today is the country’s largest provider of microcredit. It is widely known as Haiti’s alternative bank for the poor, working to promote democracy in Haiti through economic development.

Its 41 branches reach 46,000 women borrowers and more than 200,000 microsavers, mostly women and their families. It is known as the MFI with the smallest average loan size in the country (below $200), as it serves the very poor, mostly small informal traders.

It has almost as many borrowers as the entire formal banking sector (which has 54,887 borrowers). Banks and MFIs mostly operate in Port-au-Prince where 66 percent of bank branches are located. Fonkoze is the only microfinance provider that serves all of the 10 provinces in Haiti and is a vital part of the rural economy. It offers clients group loans; small business individual loans; microinsurance; savings accounts; currency exchange services and remittance services. Its foundation provides literacy and education classes, fully integrated with financial services, and helps clients and their children to access health care services in their area.

Fonkoze is internationally recognized for its comprehensive and innovative approach to poverty alleviation. In 2005 it received the Grameen Foundation’s Pioneer in Microfinance Award for its ability to break new ground in poverty alleviation while operating in one of the most challenging environments in the world. In 2009, the Haitian Studies Association, an organization of academics in the U.S., awarded Fonkoze its Award For Service. ◆ hurricane and earthquake resilient as possible, using locally available building materials while respecting the environment. Key building principles will be established such as the use of concrete poles, corrugated iron roof with timber frame, and a clean concrete floor. Home repairs are estimated to cost an average of $600, most of which will be donated by MCC in addition to a small component for sweat equity by homeowners.

MEDA’s role will be to manage the funding and provide MCC with quarterly monitoring and audit reports.

“We’re delighted that MCC is joining with us in this effort to build on our long-term partnership with Fonkoze to quickly mobilize housing support to many hundreds of clients,” says Allan Sauder, MEDA’s president. “Most of these clients are women, and we believe this is an excellent way to directly benefit the many families these women support.”

Both MEDA and MCC have long histories in Haiti, and both have been involved in other post-earthquake responses. MEDA is managing a $4.5 million grant from The MasterCard Foundation to help Fonkoze rebuild its own facilities and help 70,000 clients improve their livelihoods. MCC is involved in numerous rebuilding efforts, including emergency food distribution and relief supplies, water and sanitation needs, and trauma healing.

A spinoff will be training for local builders who will be taught safer construction techniques. MEDA in Haiti

MEDA has a long history going back to 12 cocoa cooperatives it helped create in the early 1980s and worked with for nearly a decade. (Eight of these organizations still operate successfully today.) MEDA began its microfinance work in Haiti in 1986, working primarily in urban areas. In 1994 it started REKO, a rural community banking program. MEDA and Fonkoze have worked together since the start of Fonkoze’s pioneering work to improve access to microfinance in rural areas. In 2004, MEDA turned REKO over to Fonkoze, which was growing rapidly, enabling clients to access a fuller range of services from credit and savings to business development loans. Today, MEDA is an investor and active partner of Fonkoze, providing governance as a board member and through advisory services for microfinance. ◆

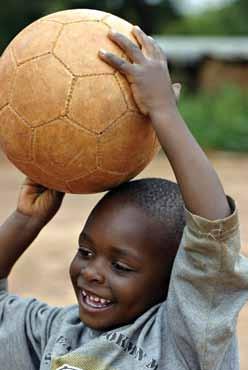

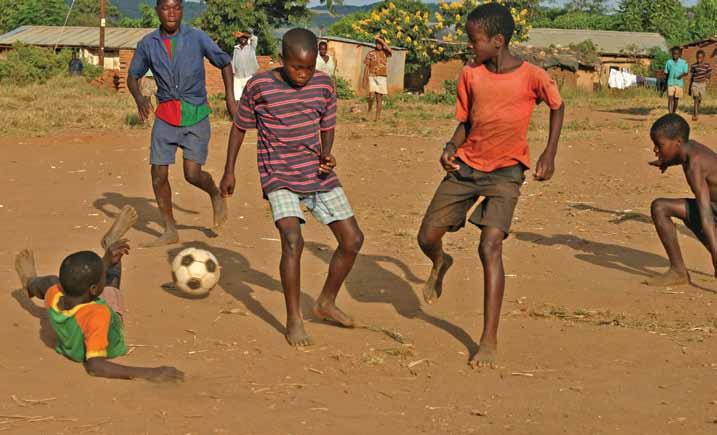

A kick at poverty

Amid the World Cup hoopla, here’s a side you may have missed

They call it “the beautiful game.”

To most of the world, it’s football. In Canada and the U.S., it’s soccer.

In one sense, the game is Big Business at play. Few other sports rival its immense salaries. The global audience for the 2010 World Cup would make any marketer drool.

Football is also the game of the poor. Visit countries where MEDA works and you’ll see youngsters turning any vacant lot into a football pitch.

It reigns supreme as the world’s game. “Soccer is one of the few things in life that cuts across all cultures, races, nationalities, religions and languages — as well as age and gender,” says soccer commentator Sean Wheelock.

“Next to Mennonite World Conference, the World Cup is the most important force for unity in the world,” quips MWC general secretary Larry Miller, a devoted fan.

In the run-up to the World Cup, travel entrepreneur

Left photo: Ray Dirks. Other photos: Carl Hiebert

Dave Guenther spent a lot of time in South Africa, the host country. He is CEO of Roadtrips Inc., which specializes in trips to international sporting events, and serves on the MEDA board of directors. He found that while sports in South Africa is still divided along racial and cultural lines (football is the sport of the black majority, rugby the passion of the white community), “kids of all races can be seen playing football. You find soccer fields and players everywhere. Sunday afternoon at the park is bound to yield an impromptu gathering of players chatting, laughing and exhibiting skills.”

As with a basketball hopeful in a U.S. ghetto, or a street hockey player in Canada, soccer holds high hopes for impoverished children in places like Africa and South America. Everyone yearns to become a Fabregas or a Kaka.

Beyond that, it is also a way to channel the energies of youth into productive pursuits. For many street children, football offers a way to escape the stigma of poverty as well as a wholesome alternative to life in gangs.

It also provides a platform to present the plight of street children and make it a mainstream development

Mennonite World Cup? Not exactly. Just a pick-up game prior to last summer’s Mennonite World Conference gathering in Asuncion, Paraguay.

issue.

This past spring a “street child world cup” was held in Durban (also a host city for the 2010 FIFA World Cup) with more than a hundred street children from eight countries. Organized by the Amos Trust, a British human rights organization, it sought to help young people set goals for themselves, get them away from crime, and encourage them to get an education.

Said one teenager who participated, “Meeting these other children helps me a lot because our stories are alike. I also think to myself that if I get a second chance, I must go back to school, and not make the same mistakes I made.”

A participant from Tanzania said the tournament showed what street children can do. For his part, “I want to become a professional footballer and play for Tanzania one day at the World Cup — and win it.”

Another child said, “When people see us playing football they don’t see us as street kids. They see we are people like them.” ◆

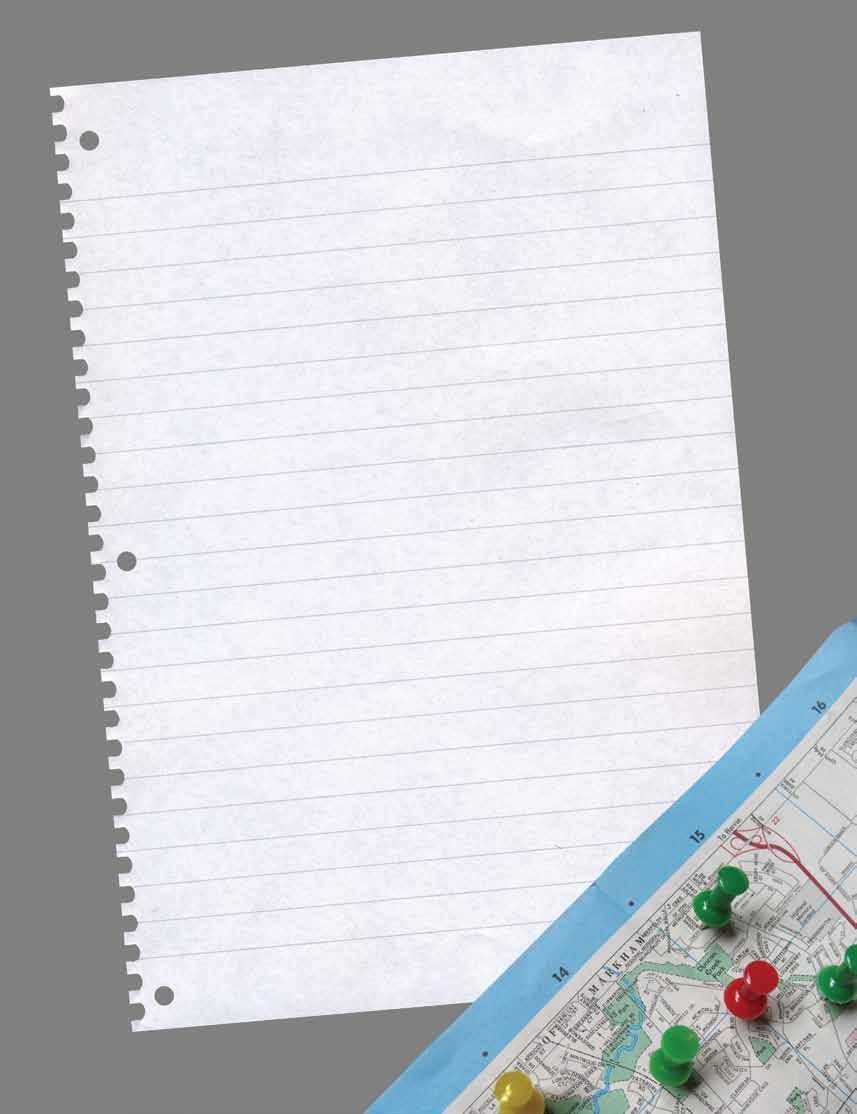

How work-friendly is your church?

Churches expand God’s reach when they celebrate the Monday-to-Friday activities of their members. The church can breathe new life into daily work — even into whole careers — by helping members reclaim the work week for God. Here are some ideas to suggest to your pastor and worship planners to help make your church a work-friendly zone. 1Map your city. Get a map of your community and mount it on a bulletin board. Use colored pushpins to show where members work (or where retired members used to work). You’ll have a visual display of your congregation’s Monday-to-Friday outreach. 2. Invite your pastor to drop in for coffee break or brown-bag lunch at your plant or office. Encourage a few friends to do the same. Your pastor will gain valuable insights into the part of life where you spend a lot of your time. 3. Volunteer to organize a series of workplace testimonies where selected members explain “How I connect Sunday and Monday.” Have them talk about their job, the day-today issues they face, and how their faith helps them witness while they work. 4. Many churches commission people for mission work or voluntary service. Why not encourage your church to do the same for Theresa the Teacher or Arthur the Accountant. 5. Plan a Sunday school elective on the theme of work. Use resources like Faith Dilemmas for Marketplace Christians (Wipf & Stock), which is designed for a 13-week quarter. You’ll find that many people are energized to talk about their work in the context of the church. 6. If you have a church newsletter, suggest that it carry anecdotes featuring members’ jobs and the challenges they face Monday to Friday. 7. Work strikes a responsive chord in worship (and not just for Labour Day weekend). Here’s a suggestion for your planners: Ask members to show up some Sunday wearing their usual work garb to illustrate the diverse cultures the congregation penetrates every week. Imagine the sight as electricians, nurses, mechanics, firefighters, medical technicians, janitors, waitstaff and office workers sport their uniforms. 8. Offer to arrange a “tools of the trade” worship display to showcase goods and services put forth by members during the week. 9. Suggest a special benediction to signal that the work week is an important part of the Christian life. Sample: “Sisters and brothers in Christ, we are NOT dismissed; we are NOT just free to go — Christ sends us. Go forth into the world in the power of the Spirit; go to help and heal in all that you do.” 10. Post a sign over the main exit door that says “Service Entrance.” But post it on the inside, not the outside. That way it’s the last thing worshipers see as they leave, reminding them that they are heading out into the world to spend the next week as ministers. ◆ 10 ways to affirm weekday ministers

Find your business in the Bible

Noah and Jesus were carpenters. Peter fished. Paul made tents.

Throughout biblical history God’s people have worked at trades, many of which are mentioned in Scripture. The list doesn’t compare with the 20,000 or so occupations available today, but it signals the importance of daily work in the Bible. Here’s a list of some businesses mentioned or suggested (based on the New Revised Standard Version).*

Accountant

Scripture doesn’t mention accountants directly, but it does mention their principles and methods. Wherever a census or an inventory of assets or offerings is recorded (Ex. 30:11-15; 2 Sam. 24; Ezra 2; Neh. 7) accountants were probably involved.

Architect

Biblical references to the tabernacle, temple, palaces and fortifications attest to the need for architects. Walled cities required architects (see Nehemiah). God is described as the preeminent architect, the “builder” and “maker” of the heavenly city (Heb. 11:10).

Baker

Bread was a major food in the ancient world (Gen. 3:19; John 6:13). The pharaoh of Egypt employed a chief baker (Gen. 40:2, 16), and a street in Jerusalem was renowned for its bakers and their shops (Jer. 37:21).

Banker

Bankers and banking were not part of the Jewish culture until the Babylonian captivity. Money as such did not exist at that time. Lending to other Jews for profit was forbidden (Deut. 23:19-20), though loans to foreigners were permitted. By Roman times, bankers were becoming common among the Jews (Matt. 25:27; Luke 19:23).

Bricklayer

Bricklaying goes back to the construction of a tower at Babel (Gen. 11:3) and the Egyptian captivity, when Hebrew slaves were forced to make bricks without straw (Ex. 1:14). The Hebrews later made brickworkers of their prisoners of war (2 Sam. 12:31). There are also numerous references to masons and stonecutters (1 Kings 5:17-18).

Builder

The first building project mentioned in Scripture is the walled dwelling that Cain constructed to protect himself (Gen. 4:17). Hebrew slaves built storage cities for the pharaoh (Ex.1:11). Their descendants built walled cities, houses, palaces and the temple. Nehemiah served as a general contractor to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem.

Butcher

The work of wild game hunters and livestock ranchers gave rise to the occupation of butcher. Some animals were declared “clean,” while others were “unclean” (Lev. 11). Paul affirmed that believers could eat what was sold at the Gentile meat markets (1 Cor. 10:25).

Carpenter

Carpenters worked with wood, metal and stone to build furniture and farm implements (2 Sam. 5:11). Scripture refers to hand tools such as the ax, hammer, saw and plumb line.

CFO

The Bible mentions several treasurers, powerful government officials who advised and reported to ancient monarchs on financial matters (Ezra 7:21; Neh. 13:13). These could be compared to today’s controllers or chief financial officers.

City clerk

Did they issue building permits in biblical times? City clerks, like the one mentioned in Acts 19:35, kept records and handled countless administrative details.

Dairy producer

Dairy products were a staple of the Hebrew diet. Milkers of cows, goats and sheep had to use the milk promptly as there was no refrigeration. One way to increase shelf life was to make cheese (Job 10:10). David enjoyed cheese or “curds” (1 Sam. 17:18; 2 Sam. 17:29).

Farmer

Agricultural references in the Bible include plows (Is. 28:24), vinedressers (John 15:1-8) and gardeners (John 20:15), not to mention livestock workers listed elsewhere. Cain was the first farmer (Gen. 4:2). See also Joel 1:11-12.

Fisher

This is one of the best-known biblical trades, figuring prominently in the life of Jesus’ disciples. It is mentioned in Is. 19:8 and frequently in the Gospels.

Forester

Loggers were said to be conservationists who practiced reforestation (Is. 44:14). Asaph was the keeper of the king’s forest (Neh. 2:8).

Garment maker

This trade is implied rather than mentioned specifically. Most of a family’s clothing was made by the women. Various trades were associated with the garment industry. Dyeing was an ancient art among families working in linen (1 Chr. 4:21), as was embroidering (Judg. 5:30) and weaving (Prov. 31:24). Lydia was a dealer in purple cloth (Acts 16:14).

Highway contractor

Roads (Prov. 8:2; Luke 14:23) and highways (Num. 20:17) are mentioned frequently in Scripture, though the people who build them are not. The work of the contractor is evoked in the famous call to “make straight in the desert a highway for our God” (Is. 40:3).

Innkeeper

In Old Testament times travelers stayed in private dwellings or slept in the open. By New Testament times some people managed inns (Luke 10:34-35). The inn which Mary and Joseph found full (Luke 2:7) could have been a large private dwelling, as it was customary to rent out quarters during festivals.

Miller

Grinding grain was the work of a miller, often a maidservant. Men would gather grain in the fields, and women would grind it using a household handmill (Luke 17:35).

Plasterer

Plastering the walls of a home to form a smooth surface (Lev.14:42-43) was an ancient and widespread craft, sometimes done by homeowners themselves.

Rancher

Those who raise cattle can thank Jabal (Gen. 4:20) for launching their trade. Abraham, too, was rich in livestock (Gen. 13:2). Those who herded other livestock, like sheep and goats, are also featured prominently in Scripture. Rachel, Moses, David and Amos all spent time as shepherds.

RV manufacturer

No, the Bible doesn’t mention recreational vehicles as we know them today. But we’ve all heard of the craft of tentmaking, made famous by Paul (Acts 18:1-3). This had to do with making affordable, mobile shelters for living, working and traveling. Some scholars say a contemporary equivalent might be the manufacture of recreational vehicles.

Secretary

Jeweler

Ancient peoples were fond of jewelry, using it for gifts (Gen. 24:22) and to adorn priestly garments (Ex. 28:15-28). Goldsmiths helped furnish the tabernacle (Ex. 25:11). In Hebrew society the job of writing and corresponding for others was done by assistants who took dictation, usually in shorthand (Jer. 36:26, 32). Paul dictated some of his letters to such an assistant (Rom. 16:22).

Silversmith

Laborer

Laborers could be field hands (Matt. 9:37-38) or workers in the general sense (Matt. 10:10). These might be manual, low-paying jobs, but their worth was considerable in the economy of God (Ecc. 5:18-20). Jesus called for more “laborers” to enlarge the kingdom. Scripture contains more than 200 references to silver and those who worked it. These artisans experienced the indignity of layoffs during Solomon’s time when gold was so plentiful that silver became nearly worthless (1 Kings 10:21).

Undertaker

Manager

More commonly referred to as “overseer,” this worker controlled or managed groups of people or projects and was generally responsible for getting tasks done. Joseph became an overseer, a position of great authority (Gen. 39:4).

Merchant

Traders and dealers sold their wares in open bazaars or marketplaces (Neh. 3:32; Ezek. 27:24-25). There are frequent references to false weights and measures (Prov. 16:11) and praise for the honest merchandising skills of the virtuous woman in Prov. 31. Egyptian embalmers (Gen. 50:2-3) developed their craft to near perfection. Among the Hebrews, who didn’t embalm, the family of the deceased washed the body, scented it with oils and spices, and wrapped it in sheets. Later, a commercial segment emerged to handle this task.

Well digger

This was a skilled profession in ancient Palestine, where little rain fell during most of the year. Wells and cisterns, the forerunners to today’s irrigation industry, were crucial to a region’s economy (Gen. 21:25). Some wells survived for many generations (John 4:6). ◆

Metalworker

Foundry workers melted, refined and cast ore into useful metals (Jer. 6:29; 10:9). Tubal-Cain made tools of bronze and iron (Gen. 4:22). Hiram of Tyre was engaged by Solomon to make bronze pillars for the temple (1 Kings 7:13-22).

* Adapted from The Word in Life Study Bible, copyright 1993, 1996 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission.