56 minute read

Soul enterprise

Pastors and businesspeople: Bridging the gap

When businesspeople have a tough decision to make, how often do they go to their pastors?

Almost never.

In a study done a few years ago, businesspeople ranked clergy ninth — behind “no one” — when asked whom they consult in making decisions about business.

When the chair of the business department at a Christian college conducted a similar survey, he found that only 9.4 percent of the businesspeople in his community would consult their pastors in dealing with financial difficulties.

“That says something about our relationship to the church,” he wrote. “It also says something about the church’s relationship to business.”

Now, to be fair, not all business decisions require a call to a pastor. But still, the fact that clergy register so low on the list of who to call doesn’t bode well for the church — and maybe not for Christian businesspeople, either.

Why so little contact between clergy and businesspeople? One reason is that businesspeople may be reluctant to talk on Monday to someone who was preaching on Sunday about the evils of money, materialism and consumerism. Why ask advice from someone who seemingly has nothing good to say about money or spending it?

Another reason may be that the only time some businesspeople expect to hear from their pastors is at budget time — money is the root of all evil until the annual fundraising campaign kicks in. An old adage about Christians and business goes: “If possible, avoid getting into business; but if you do get into business, avoid making lots of money; but if you end up making a lot of money, the church sure needs it.”

Finally, pastors and businesspeople may have different ways of viewing the world. For example, businesspeople prefer practical measurements such as profit and loss, while pastors may talk about “kingdom values.”

Pastors are more comfortable with process and consultation, while businesspeople often have to make quick decisions with a minimum of discussion. Pastors may describe justice for the poor in terms of redistribution of wealth, while a businessperson may talk of it in terms of wealth creation — jobs and improved economic opportunities.

How can pastors and businesspeople bridge this gap? One way would be for pastors to visit their members’ workplaces, just as they visit their members in hospital. Through the visits they could see what their members do during the week, and get a firsthand perspective on some of the tough decisions businesspeople have to make — hiring and firing, expansion, dealing with unions, etc. Likewise, businesspeople could take time to hear how a pastor has to juggle various interests and personalities to reach a decision in the church, how carefully they have to weigh what they say on Sunday morning, and how they struggle with the enormous expectations that others place on them. Seminaries can play a role, too. Just as they teach prospective pastors how to make hospital visits, they could help them learn the importance of workplace visits. Just as they teach liturgies for weddings and funerals, they could teach liturgies to commission Christian teachers, plumbers, lawyers and other people in the workplace. Maybe then pastors can move ahead of “no one” on the list of whom businesspeople consult when making a decision. — John Longhurst

Advice to aspiring entrepreneurs

“Follow your heart and passion and find a way to contribute to the world beyond simply making money. Truly serving others the way you want to be treated is much more fulfilling than simply making money. Just making money is boring.” — Dan Price, co-founder and CEO of Gravity Payments and winner of the 2010 Small Business Association’s Young Entrepreneur of the Year award

Sanctifying the corporate world

You don’t usually expect to see religious faith featured in the Wall Street Journal, but a recent op-ed piece was titled “Doing God’s Work — At the Office.” Its author, Rob Moll (who also produced our feature interview on page 6) reports on growing numbers of Christians who see their business careers as a place to live out their values.

“Christian business professionals have long had an uneasy relationship with the church,” he writes. “Not only does the church tend to privilege church and missionary service over business, but it often condemns business practices and implies the guilt of any participants. Yet there are signs that this dynamic is changing — not least because churches rely on the donations of business professionals.”

Moll says more and more pastors now visit their parishioners at work, quoting one who explains, “It shows them that I care about their callings, how they spend 50-plus hours of their week.”

The new mindset is expressed by Dave Evans, co-founder of videogame giant Electronic Arts, who “talks more like a theologian than a former Apple engineer.” Evans, Moll reports, believes Scripture teaches “that humans were created in the image of God, so all of our work — not just church work — is holy. We are called to be co-creators, with God, of a flourishing life on Earth.... When he began work in the 1970s, integrating faith and business amounted to little more than being ethical and trying to make converts. Much has changed, he says, as a younger generation seeks to sanctify the corporate world.”

Another executive, an equity strategist, is quoted as saying that on-the-job pressure provides an opportunity to “live out your faith in front of colleagues. How do you treat employees? Do you lose your temper?”

Theologian-for-hire

It seems there is no end to the kinds of jobs clever people can fashion for themselves. Anna Madsen discerned a market niche for a sort-of-pastor and sort-of-therapist and started a business as a freelance theologian. Her company, based in Sioux Falls, S.D., is called OMG: Center for Theological Conversation. “I realized that if someone is theologically out of whack, then that person’s whole life is out of whack,” she says. — Christian Century

Overheard:

Burden-bearing in the office

“People fear showing love in a dog-eatdog world. One evening, I overcame that fear and asked a colleague for advice on a stressful situation. I told him I was on the verge of drowning. He gave lots of advice and volunteered to help me, which I accepted with gratitude. Just as I got up to leave, he asked me if I knew anybody who provided help to drug addicts. He said his daughter had been arrested by the police and tested positive for drugs. Tears rimmed his eyes. He felt he’d failed as a father. ‘I don’t know what to do, but I’m willing to do anything to help my daughter,’ he said. At that moment, I felt God’s loving presence with us. My colleague and I were openly bearing one another’s burdens. My colleague demonstrated love by taking time to listen and provide astute advice. And I sought to love my colleague by supporting him in his personal pain.” — Alvin Ung in Taking Your Soul to Work

“It’s a sin to die rich.” — Chocolatier Milton S. Hershey

The meaning of business

Christians in the marketplace, says Jeff Van Duzer, are not second-class citizens of the kingdom

Interview by Rob Moll

Despite many books and conferences in the past decade that frame business as a divine calling, churches still wonder how best to support the businesspeople in their midst, many of whom feel demeaned for not doing “real” ministry.

Jeff Van Duzer, in Why Business Matters to God (And What Still Needs to Be Fixed) (IVP, 2010), offers businesspeople guidelines for how to think about their role in God’s plan. Christianity Today editor at large Rob Moll spoke with the dean and professor of business law and ethics at Seattle Pacific University about whether the free market system is still the best provider of goods and services, and how churches can help businesspeople face ethically complex choices.

Why does God want people to go into business?

Two answers: to provide goods and services, and to provide meaningful and creative jobs.

Those are two different purpose statements. One has an internal focus, and one, external. Externally, business is the only institution that creates economic value. A university provides intellectual capital but does not make things. Business takes the ideas and commercializes them. It relies on an array of values from other institutions, but it’s the only one that adds value into the system. Business plays a key role by creating products and services.

But not every product a business could make is equally valid in the eyes of God. So a Christian in business should ask not only what will maximize the bottom line, but also what product or service could be made, given the core competencies under his control and the assets he is managing, that would best serve his community.

The second piece is that God designed humans to work. They are made in his image; God is a worker. And God’s work is creative and meaningful. Business is not the only institution that creates opportunities for work, but it is certainly one of them, and this recent recession would suggest it is a very important one.

What is the purpose of business?

A business should serve — internally, its employees, and externally, its customers. A business exists for certain purposes. One purpose is to provide meaningful work. Another is to provide meaningful goods and services. It does not exist to maximize return on capital investment. There are a variety of things you might include that enable you to achieve those service goals, but you should not do anything that runs afoul of limits. A broad understanding of the notion of sustainability might be shorthand for describing limits. As business pursues what I think are its godly purposes, it must do so in a way that does not transgress the “do no harm” standard of sustainability.

The third purpose is partnership. It’s a call for business to recognize its place in a system of institutions that collectively pursue the common good. The common good allows for the flourishing of the community and the individuals who make up that community.

Haven’t we seen a flood of books over the past decade arguing that business is not only a legitimate calling for Christians but even a high calling? Why the need to continue highlighting this theme?

There has been emphasis on the broader understanding of vocation and calling, and a broader concern about a dualistic — Monday through Friday versus Sunday — Christianity. Even in our church, every now and then we will hear that someone is being called to “Christian ministry,” and you know they are not talking about accounting.

Businesspeople often complain that the church subtly communicates that their calling is a necessary evil or at best a second-class vocation. Is this a legitimate complaint? If so, why do churches approach business like this?

Yes, it is [a legitimate complaint]. The entire world is the Lord’s and all the work we are called to do is ordained by him, in service to his kingdom. There are a lot of people

Jeff Van Duzer: “If we live in a fallen world, how do we live in this messy middle?”

who have done sociological studies and have written about how businesspeople feel demeaned by the church, though I think the church is getting better.

What can churches do to communicate to businesspeople the value of their calling?

Church leaders need to understand and learn about what is involved in the day-to-day lives of parishioners. They need to know how theology applies in the lives of people; if they don’t know their lives, they can’t apply their theology. Hold a conference and invite business leaders to talk about the challenges they are facing. Go to the workplace and ask questions. Leaders need to be careful with their language. There has been improvement, but there is still a tendency to refer to some things as ministry and others not. Pastors need a richer understanding of the pluses and minuses of capitalism. They know the minuses, which often enough are true. But it comes across as if businesspeople are dancing with the Devil. Another thing churches can do is celebrate Christians in different professions.

Businesspeople complain about the church’s attitude toward business. But don’t businesspeople see the church as wishy-washy, touchy-feely, or out of touch with the real world?

Absolutely. I talk about this in the context of the call to partnership. Various institutions tend to see themselves as godlike. They demand loyalty and insist on the extension of their characteristics into other spheres. Government and the church can be disdainful and distrustful of business, and certainly business is disdainful and distrustful of government. We need to see other institutions as common allies in support of a common mission for the good of humanity. We would then say to business [institutions] that they shouldn’t apply their metrics, like efficiency, to an artist or a church committee. There are other values embedded in the nature of those institutions that need to be respected.

You say that the free market is in the best position to deliver goods and services. In today’s economy, can we be so confident that this is still true?

Don’t make my claim stronger than it is. I certainly don’t claim godlike status for markets. In fact, I think the free market is one of the great idols of our age, particularly among Christians in business. The market’s claim is to send price signals to allocate resources. That is just one of a number of goods that society should hope to have, and it’s

“The best way

you can unleash a long distance from shalom. Government should creative juices play a significant role in creating some protections against bubbles and is to help other things that distort market signals. However, employees relative to state-directed economies, the free understand market is more efficient at allocating resources.

that their work Some socialist democconnects to racies, like the Scandinavian countries, have something bigger, managed to produce goods and services as well as further something that the common good, offering an array of has long-term social services like free health care and value.” free education. Isn’t this a better economic model for society, given your ideas?

I sometimes get accused of being a socialist. But there is a fundamental difference between the view of business I argue for and a socialist economy. In a socialist system, the government is directing the economy. I’m not talking about that. What I’m saying is that individual Christians should align their vocations toward godly desires.

Every system has a mix of government direction and the free market. There are a number of ways government can help the market run more efficiently. Different cultures draw the line in different places. I’m addressing Christians in their world and in business.

Your vision for Christian business would not be recognizable in many business schools.

There is a significant minority movement in business in which people are saying that business has to be about more than just maximizing the bottom line. You can find it in what’s called creative capitalism or conscious capitalism. None of those ideas are precisely what I’m advocating. But they are not so far away that someone would look at mine and think I was from Mars.

Some argue that your idea — that the purpose of business is to help the common good — is old, and that “maximizing profit” for its own sake is the new idea. Do you think this is true?

Historically, maximizing shareholder value as the purpose of business has not been the prevailing view. The notion of maximizing shareholder wealth dates back to the 1970s. Companies that existed before that had a different initial understanding of what they were about. This is a recent and fairly destructive idea that came about through various and complicated reasons.

Do any companies practice business in the way you advocate?

It’s hard to tell. A lot of what I’m talking about is motivational. We have Costco here in Seattle. Its mission statement — “To continually provide our members with quality goods and services at the lowest possible prices” — aligns directly with what I’m saying. As a practical matter, shareholders have done very well. It’s possible that the CEO goes home at night, laughs, and says that what he’s really about is maximizing returns — but I don’t think so.

Would someone following this model be at a competitive disadvantage?

I don’t ever want to suggest that doing the right thing will always redound to the bottom line. The phrase “good ethics is good business” is true most of the time. If all ethics made money, we would never teach ethics at business school. Increasingly the value and wealth of a company is tied up in the creativity of employees. Even if the only thing you care about is making money, you want to unleash those creative juices. The best way you can unleash creative juices is to help employees understand that their work connects to something bigger, something that has longterm value. A model that tells you to think about how your company can best serve the community is also the model that’s most likely to tap into employees’ creativity.

Most Christians are employed by businesses that don’t follow your model. What is your word for them?

This is the most important question churches could be talking about today. If we live in a fallen world, how do we live in this messy middle? When is it okay to compromise? When do you pay a living wage and ride the company into bankruptcy because it’s the right thing to do, and [say], “If God wants to rescue it, then he will”? Or, when do you say you want to pay a living wage, but you just cannot make it pencil out?

Christians can’t accept a position of compromise until it is the very last option. They have to strain for that creative solution that allows them to do it all. Then, when they are absolutely forced to choose the lesser of two evils, they have to acknowledge that nonetheless, they are choosing evil. That should call them to confession, repentance, and a deep longing for the day when we won’t be living in this kind of world anymore.

I wish the church would help us think through principles about how to navigate this messy middle. I try to provide a theology that will help businesspeople understand how their activity can fit into the overall scheme of God’s kingdom work. ◆

This article first appeared in the January 2011 issue of Christianity Today. Used by permission of Christianity Today International, Carol Stream, IL 60188.

The market and the messy middle

It may not be perfect, but it’s still part of God’s plan

Review by Craig Martin

Why Business Matters to God: (and what still needs to be

fixed). By Jeff Van Duzer (InterVarsity, 2010, 206 pp. $20 U.S.)

The questions: What is the purpose of business, and what does it mean to be a Christian in business, are the seeds of inspiration for Jeff Van Duzer’s book Why Business Matters to God: (and what still needs to be fixed). Van Duzer challenges the resulting dichotomy that “work (and its product) remain neatly divided between the secular (which hardly counts) and the sacred (which is ultimately all that matters).” He finds this is bad theology in that it “limits the advance of God’s kingdom” and God’s power to work through business to advance the divine plan. In doing so he starts the needed conversation about developing a Christian theology of business.

The first major challenge Van Duzer faces is that “in a narrow verse-by-verse sense there is not much to work with” in terms of biblical Scripture. As a result, rather than trying to create a theology of business based on a “handful of specific verses,” he bases his theology on what is called the “grand narrative.” This theological method states that all Scripture tells one basic story in four great movements: Creation, the Fall, Redemption and Consummation.

In the first part of the “grand narrative,” Creation, we find God’s initial purpose for creation and for humans within creation. That initial purpose is two-fold: (1) God’s creation, including humans, is to flourish, multiply and fill the earth, and (2) humans were to work with God to bring creation into its full glory. From this general purpose for all of creation, Van Duzer establishes his theology of business: (1) businesses are to “provide the communities with goods and services that

Excerpt: A place to serve

“The purpose of business is still to serve. It is to serve the community by providing goods and services that will enable the community to flourish. And it is to serve its employees by providing them with opportunities to express at least a portion of their God-given identity through meaningful and creative work.” — Jeff Van Duzer

Excerpt: Work harder

“...there is reason to suspect that Christians should become some of the most creative innovators in business.... When Christians become aware of tensions between their vocation as followers of Christ and their vocation as businesspersons, they must work harder to uncover new possibilities consistent with both callings.” — Jeff Van Duzer

will enable it to flourish, and (2) to provide opportunities for meaningful work that will allow employees to express their God-given creativity.”

However, we are no longer in the

Garden but are subject to the Fall. This means that all of the intended relationships, “God-human, human-human and human-natural order,” are broken and not as God has intended. It is into this environment that we must place the institution of business. Van Duzer argues that business, like all human-run institutions, is subject to the consequences of the Fall. Therefore, “markets are not how God intended human beings to carry out exchange” and whether “markets would have developed even without the Fall” is questionable. However, given our fallen state, God is able to utilize the market system to carry out at least part of the initial plan. As Van Duzer points out, to date “the market system is the most efficient system used by humans” to allocate resources compared to central planning, feudalism, etc. But, we must always remem-

Excerpt: What business does best

“Business leaders have great skills. They are the best at getting the most out of a little. They can organize and deploy resources with remarkable efficiency. They tend to be optimistic and willing to take calculated risks. They are trained to look for possibilities where others just see problems. They are trained to look for a third option — the creative win-win solution that can break through deadlocks. And they often have the capacity to gather substantial resources to direct toward needed solutions. Big challenges motivate them and they tend to persevere in the face of tremendous odds when convinced they are on the right path.” — Jeff Van Duzer

ber that the market “is a product of the Fall and therefore unable to bring about God’s designed conclusion, in other words the market is not perfect.”

Given the fallen nature of both humans and

markets, what is a Christian in the business world to do? For Van Duzer the solution is that businesspeople need to operate and manage their businesses in a manner that is sustainable. In this he not only means to be sustainable in an environmental sense but also with respect to all stakeholders, shareholders, employees, suppliers, customers and communities. This means that shareholders deserve “a reasonable, risk-adjusted return on their investment.” For employees this means being treated as having “intrinsic value not just as a means of production.” This means that suppliers are “entitled to honest and transparent dealings.” Customers “are entitled to know what they are purchasing” and that the products “meet their reasonable expectations for usefulness and safety.” In terms of communities, businesspeople must deal with them in a “sustainable fashion” that recognizes that communities provide other forms of capital that help God’s creation to flourish. The challenge for businesspeople is to balance each of these requirements which can at times be in conflict with each other. Van Duzer therefore places the institution of business firmly within God’s plan but, like all things since the Fall, it is not perfect and there is still much that needs to be done.

This book is a necessary read for any businessperson who takes both their business and faith seriously. Almost more important, however, is that this book should be read by Christians outside of the business world. ◆

Craig Martin is assistant professor of business and organizational administration at Canadian Mennonite University, Winnipeg.

Wet & wild

How can we part the water through daily showers and double espressos?

by Al Doerksen

Igrew up in a family with eight kids. We never had a lot of money but I don’t recall thinking we were poor. We did have water restrictions however. We bathed once a week in three to four inches of shared water, and just doing number one in the single toilet was not sufficient reason to flush.

The driver for these family rules was not water scarcity — it was a captive sewage system that had grossly inadequate absorptive capacity especially in our frozen Alberta winters. Water consumption, however, was never an articulated concern in my growing up years; we added ice cubes and tea bags and instant coffee as often as we wished, and the hoses ran freely when flooding the community hockey rink. In our local Mennonite church, water was a symbol of everlasting life and the medium of baptism.

Well, that was 50 years ago. Now I enjoy my daily showers. I have graduated to double espressos and I no longer play ice hockey, but I confess that concerns about excessive flushing are still in my psyche. In terms of its psycho-metaphorical value, water thoughts seem to generate more feelings of guilt than grace.

The messages these days, with so many dire predictions from the water Malthusians, are not encouraging. Water tables are dropping. The world is running out of fresh water. We’ve got a time bomb. Our water is getting more and more polluted with agricultural pesticide and herbicide run-off, and industrial complexes still flush with abandon. The next wars will allegedly be fought over access to water, and every double espresso I consume uses up 140 litres of water. Eating beef is even worse — one kilo is like consuming 16,000 litres of water — enough water to fill the pool we no longer own. I am part of the fortunate middle class world which owns a completely unsustainable water footprint — 2,500 cubic meters per person per year. One could drown in the statistics (and in the empty water bottles). All of this gives me a headache; I wish it was just the consequence of dehydration on a hot day.

My first water career was with Trojan Technologies, winner of the 2009 World Water Week Industry Award for its global leadership in the development of large-scale ultraviolet water disinfection systems. Our concerns were about safe (chlorine-free) drinking water, about safe discharges of waste water back into the environment, the removal and destruction of industrial contaminants in the ground water and river systems. I was based in Europe, where the EU Water Frameworks look at water from a river basis perspective. The Rhine is used for agriculture, fisheries, industry, transportation, recreation and tourism, and using its water must accommodate the interests of all.

My second water career is with International Development Enterprises. We encourage the productive use of water; in our experience irrigation is one of the best leverage opportunities available for smallplot dollar-a-day farmers. We offer affordable technologies to pump/lift water, store water and distribute water. The trouble with irrigation, however, is that it uses water — on average six litres per square meter per day in irrigation season. Some days this feels perverse; in a waterstressed world, we are promoting the use of more of it. We are not likely to be able to wean ourselves off food and water, however, so our focus, especially in agriculture, which uses 70 percent of available fresh water supplies, will increasingly promote the more careful stewardship of this resource.

A recent report by the International Water Management Institute, “Water for Food, Water for Life,” acknowledges the challenges ahead. It says, “The hope lies in closing the gap in agricultural productivity in many parts of the world … and in realizing the unexplored potential that lies in better water management along with non-miraculous changes in policy and production techniques. The world has enough freshwater to produce food for all its people over the next half century. But world leaders must take action now — before the opportunities to do so are lost.”

At IDE we will continue to pursue innovative approaches to more responsible use of productive water. On the other hand, we will deepen our inquiries about falling water tables.

And I will continue to be conscious of my flushing habits. ◆

Al Doerksen is CEO of International Development Enterprises, Denver.

Who says?

Quotations and proverbs are grist for sermons, speeches and clever conversation. But who said them first? Take the following test and check your Business I.Q. (For “I’m quoting...”). Disclaimer: our use of these quotations does not mean we agree with them (but we might).

1. “In capitalism, man exploits man. In socialism it’s the other way around.” (a) Cal Redekop (b) R.H. Tawney (c) Max Weber (d) none of the above

2. “Greed has been severely underestimated and denigrated. There is nothing wrong with avarice as a motive, as long as it doesn’t lead to anti-social conduct.” (a) Conrad Black (b) Milton Friedman (c) Gordon Gekko (d) H. Winfield Tutte

3. “I never let politics or religion affect my business knowingly.” (a) Malcolm Forbes (b) Lee Iacocca (c) Jimmy Pattison (d) Jack Welch

4. “I don’t have time to be nice.” (a) Harold Geneen (b) Howard Hughes (c) Wally Kroeker (d) Gustavus Swift

5. “Few trends could so thoroughly undermine the very foundation of our free society as the acceptance by corporate officials of a social responsibility other than to make as much money for their shareholders as possible.” (a) Milton Friedman (b) John Kenneth Galbraith (c) John Maynard Keynes (d) Thorstein Veblein 6. “A holding company is the people you give your money to while you’re being searched.” (a) Tony Campolo (b) Bill Maher (c) Will Rogers (d) Rush Limbaugh

7. “When someone gets something for nothing, someone else gets nothing for something.” (a) Ogden Nash (b) William Shakespeare (c) Jeffrey Sachs (d) none of the above

8. “Always do right. This will surprise some people and astonish the rest.” (a) Winston Churchill (b) Sam Janzen (c) Mark Twain (d) Gerhard Pries

9. “The first step in the evolution of ethics is a sense of solidarity with other human beings.” (a) Ivan Boesky (b) Dietrich Bonhoeffer (c) Albert Schweitzer (d) none of the above

10. “Wealth consists not in having great possessions, but in having few wants.” (a) Epicurus (b) Mohandas Gandhi (c) Warren Buffet (d) Mother Teresa 11. “When I feed the poor, I am called a saint. When I ask why the poor are hungry, I am called a communist. (a) Mohammad Yunus (b) Michael Moore (c) Dom Helder Camara (d) B. Boku

12. “If a man write a better book, preach a better sermon, or make a better mousetrap than his neighbor, the world will make a beaten path to his door.” (a) Ralph Waldo Emerson (b) Benjamin Franklin (c) George W. Bush (d) Henry David Thoreau

13. “He who builds a better mousetrap these days runs into material shortages, patent-infringement suits, collusive bidding, discount discrimination — and taxes.” (a) Peter Drucker (b) H.E. Martz (c) John Naisbitt (d) Thomas Peters

14. “Professions, like nations, are civilized to the degree which they can satirize themselves.” (a) Ted Swartz (b) Garrison Keillor (c) Eleanor Roosevelt (d) Peter de Vries

15. “The trouble with the publishing business is that too many people who have half a mind to write a book do so.” (a) Michael Korda (b) Alfred Knopf (c) Ron Rempel (d) William Targ

1. d; 2. a; 3. c; 4. a; 5. a; 6. c; 7. d; 8. c; 9. c; 10. a; 11. c; 12. a; 13. b; 14. d; 15. d

Answers:

What would you say to Menno and Vera?

Those who work at “secular” jobs, whether in business or other professions, are not always seen as active Christian servants. Some are even regarded as second-class citizens in the kingdom of God.

Not all of us are gifted to be pastors or missionaries. Nonetheless, we too have been given occupational assignments through which we can be God’s junior partners in meeting the daily needs that help sustain God’s creation. Scripture suggests that our daily work is a calling through which we can exercise the gifts God has given us.

It was a quiet Saturday evening. Menno and Vera Wenger were relaxing in their favorite chairs after an active week in the business they jointly owned and operated. Menno pondered the financial reports he’d just read. They gave him a sense of both joy and dread.

Profits were up. Menno was grateful for a good year, for their thriving company, for their 22 employees. On the other hand, he felt unease because ticklish decisions lay ahead.

Last year profits had been small, leaving few things to decide. They merely increased wages where they could. What little surplus was left went to upgrade equipment and hire two new employees. Menno and Vera’s personal income had been only slightly above average for people in the area.

Menno wouldn’t forget the last time profits had been this good. They had added a production line, hired seven more people, and built a much-needed warehouse. It was a handsome building, conspicuous from the main road. Its visible location gave customers easy access and projected a dynamic image.

That, unfortunately, had been the problem, at least for people quick to criticize. Menno and Vera felt the sting of comments, only half-humorous, that they were building a monument to themselves. Someone joked that it housed an indoor golf course. Another muttered about “a license to steal.” That hurt.

Menno almost wished this year had been like the last. He didn’t relish making choices that would bring more sarcasm.

People didn’t understand how vulnerable the company was. They didn’t realize that running a business meant being in a permanent relationship with the bank and having to worry constantly about the prime rate. Things were going well now, but the market was unpredictable. To stay competitive in a changing environment, they needed more trucks, a bigger building, and at least seven or eight more workers.

That last part felt good. It was fulfilling to Menno and Vera that their vision and hard work created good jobs at competitive wages. Their employees meanwhile were building their own capital base. Out of it they sustained their families, paid for houses, helped finance schools, and generally contributed to the community. When the Wengers created new jobs, they almost felt as if they were doing the Lord’s work, though they wouldn’t describe it that way at church.

Ah yes, church. Tomorrow was Sunday. Menno and Vera would encounter some employees and their families. Would the Wengers’ looming decisions interfere with their worship? What would be the mood of the service and the sermon topic? Would they feel joyous or guilty?

Questions to ponder:

1. To whom in the church can the Wengers go for counsel and sharing? What can be done to create a safe environment? Is the church the place for this kind of sharing? 2. How should the Wengers balance priorities? Should they expand the business? Give more in wages, bonuses, and benefits? Give more to the church and charities? What Scripture would be helpful? 3. Let’s say you’re the pastor of a church which includes people like the Wengers as well as others who don’t understand the Wengers’ dilemma. How would you plan next Sunday’s service and message? How would you bridge different viewpoints? ◆

This article, written by former MEDA president Ben Sprunger, is taken from the book Faith Dilemmas for Marketplace Christians (available on the MEDA website: www.meda.org)

Singapore and “Garbage City”

A globe-trotter ponders the possibilities of unleashing entrepreneurship

by Donovan Nickel

During the past 10 years, before retiring from Hewlett-Packard Co. in July, I led two of the company’s global business divisions. In developing those businesses, I traveled 60-70 times to Asia, more than to any other region outside North America. I found the emerging markets in Asia compelling, for the energy, the openness to learn and adopt new technologies, the amazing levels of investment and risk, and the aggressiveness to make things happen right now. The pulse rate of business decisions, and of entrepreneurialism, is faster in emerging market economies than in developed economies, and I loved it.

Examples: the $1 billion company in Taiwan that was willing to invest $3 billion in a new factory (how many $50 billion western firms are willing to put $3 billion in a new North American factory?); the start-up in Beijing that had office space located, under contract, configured with data center, furnished, and operational in a week; the South Korean firms that went from groundbreaking to sales on a new semiconductor factory in nine months (working six long days per week, lunch standing up); my own experiences setting up and growing engineering teams in Bangalore and Singapore.

iStockphoto, Andrew Wood One of my favorite examples of unleashing entrepreneurship on a large scale was the development of Singapore — I always thought of it as “Asia for beginners,” with its excellent infrastructure and the use of English for business and education. When Singapore became an independent republic in 1965, it was a poor, small island country with no natural resources, no manufacturing base, little industrial know-how, very little domestic capital, and major unemployment. Lee Kuan Yew and the early leaders established key development strategies to attract foreign investment to develop their manufacturing and financial business sectors. They offered what they could. First, a low-cost, industrious labor force with a strong quality and productivity orientation, and a labor union focused on keeping labor productivity competitive. Second, tax structures with significant long-term incentives for foreign firms. (Singapore won here over other developing countries due to its relatively incorruptible government and early investment in infrastructure.) As unemployment dropped and a labor shortage arose, emphasis was placed on efficient usage of labor through education/training, automation and computerization technology. Tax incentives evolved to encourage local research and development and financial management in addition to manufacturing. The result was a remarkable 40-year development cycle which achieved the highest per capita GDP in Asia outside Japan, very low unemployment, one of the Strategic development: A Singapore school child assem- world’s top three shipping ports, a strong base of technolbles a model of the DNA spiral. ogy, and in recent years, increasing local innovation and

Donovan Nickel

In some of the most unlikely circumstances we found savvy teenagers who see a path to a better future

entrepreneurial business start-ups.

I could add that Singapore is also where you find the world’s favorite airline, great hotels, the best chili pepper crab, and the tailor who makes my suits, but I want to shift attention from emerging markets back to the first step — Frontier Markets.

My experiences work-

preneurs turning garbage back into raw materials and the raw materials into new products for sale (scrap fabric into new rugs and handbags, old newsprint into pulp slurry and then into new heavy-grained paper and then the paper into greeting cards, calendars, and other products).

It was satisfying to see MEDA’s initiatives focused on the education of children who work in a country where child labor is big. This educational program teaches a workplace code of conduct, gender equality, child labor rights — and it also teaches computer skills, business risk and mitigation, and entrepreneurial business management. These teenage kids are savvy and world-wise beyond their years — many will not have future opportunities through higher education and employment, but they see a path to greater future opportunity through entrepreneurship.

Our faith and values call us to be helpful stewards in our worldwide community. But we know that turning good intentions into effective actions and outcomes is hard. That’s why I’m a big fan of MEDA’s mission and programs. It’s why I’m a member, a contributor, and an investor in Sarona Funds. It’s a long-term commitment, but past examples of frontier markets like Singapore showed what is possible to achieve in 40 years, so let’s keep at it. ◆

ing within emerging market countries that were frontier markets only a few decades ago have amplified my personal enthusiasm for MEDA’s mission to develop sustainable business solutions to poverty in frontier markets.

A year ago, my wife Jewel and I joined a MEDA trip to Egypt. By way of comparison, it’s clear that Egypt as a country is missing some of the development strategies Singapore put in place years ago. The people we met in Egypt, though, have a strong propensity for free enterprise and entrepreneurship, even in unlikely circumstances.

We met a seven-year-old entrepreneur while wandering through the Aswan town market one night. He was amazing. He had a very confident and friendly approach. He had his sales pitch down cold. He had an answer for every question. And after about 15 minutes of work, he closed the sale — we squandered a couple of dollars for a handful of bookmarks. That young man has potential!

On the outskirts of Cairo is Manshiyat naser (Garbage City) — the place where 5,000 tons of trash is brought each day. Some 60,000 people live there and go through all the trash by hand, sorting, recycling, reusing. It was impressive to see impoverished but creative entre-

Donovan Nickel, a retired divisional vice-president for Hewlett-Packard, lives in Windsor, Colo. His article is based on comments to MEDA’s Unleashing Entrepreneurship convention in Calgary in November. Carl Hiebert photo

Frontier market: A client of MEDA’s Egypt project works on a computer in a family company.

Women’s empowerment Revolution in Pakistan’s embroidery belt

Meher Afroze Baloch used to be “a simple housewife” who had a knack for embroidery. Her designs were outdated and not up to market standards, but adequate for household use. Then she came upon a MEDA project in Pakistan and a whole new world opened up.

The three-year $1.2 million project is helping birth a small economic revolution in a corner of South Asia’s “embroidery belt” in mountainous northern Balochistan, one of the most remote and impoverished areas of Pakistan.

Due to local cultural norms, women are sequestered and isolated, so engaging them in any enterprise is difficult. “Women’s economic empowerment in Balochistan is an enormous task that requires a concerted and deliberate effort,” says Helen Loftin, MEDA’s director of women’s economic development. Challenges include deeply-rooted cultural norms against women’s inclusion in any activity outside the home, as well as the overall insecurity of the region.

But working through its partners, WESS (Water, Environment and Sanitation Society) and ECI (Empowerment through Creative Integration), MEDA is helping 5,000 women embellishers to share vital market knowledge and business skills, and connect with viable markets. In turn, the women are earning more income and economic power that will help them assume a more active role in

Pakistan’s embroidery belt

Participants examine the handiwork of women embellishers from northern Balochistan.

Any happy occasion in Pakistan, along with food, music and fun, also calls for a special dress, and more often than not, women turn to hand-embellished fabric. The quality can vary, with the price ranging from very expensive to reasonable. Embellishments are applied on varied and special motifs and designs, some of which date back to the Mughal era (1526-1857) and beyond.

Take, for instance, the timeless paisley and geometrical designs very conspicuous in Islamic art and popularly used in the phulkari (flower patterns) embroidery. The materials used include cotton and silk threads, glass mirror pieces, beads, shells, buttons and designed metal pieces.

Geography and culture exercise a significant influence on the type of embroidery and color used. This is especially true of the “embroidery belt” which stretches from the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) to the Thar desert and across Gujrat to Rajasthan in India. This particular area in the subcontinent boasts the largest variety of embellishment styles and the people are highly skilled in their craft. South Asia has long been famous for its beautifully embellished cloth, with the exquisite work often produced by women as they find time around household chores. Girls learn this skill from their mothers or other women of their family and prepare embroidery pieces for their dowry. In rural areas it is common to use embroidered textiles to beautify living spaces. Very fine embroideries are handed down from generation to generation and are framed and kept protected in urban homes as well. — Linda Whitmore

household and community decision-making — no minor feat in a tribal and deeply patriarchal society.

Meher’s story is typical. As part of a slightly more mobile class of women, she became a sales agent for the project and gained exposure to markets in Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad. “I had the opportunity to see new designs and products as well as receive training in color combination as well as product diversification,” she says. She feels that the quality of her work has substantially improved after her exposure to different areas of the country. “Now, I’m a more confident person and can deal directly with the market. I can work “Just inviting a better with local women embellishers and guide them in their product design and woman to the quality with respect to market demands.” dais to speak Meher and other participants had a chance to at an event like network and tell their stories recently at a two-day conthis shows how ference and exhibition that attracted 292 participants much progress and 22 exhibitors — from women embellishers and has been made female sales agents to input suppliers, wholesalers, retailers in Balochistan.” and supporting organizations. Shakila, a fabric embellisher, has been doing

Balochistan — remote and illiterate

• Pakistan’s largest province — but mountainous and remote, with very low population density • High rates of poverty, illiteracy, unemployment, and infant and maternal mortality • Literacy rates lowest in the country — 18% among men; 7% among women

Meher

Shakila

Rozina

embroidery for 10 years. In three months with the project, she has had multiple opportunities for training. “The most attractive feature of the project is that I can work out of my house and still earn a stable income,” she says. “A project like this is very beneficial for women like me who were unable to go to the market, so couldn’t sell our products at market-based, competitive prices.” In addition to better embroidery skills, the project has given her better business sense and enterprise skills, Shakila says.

Rozina, a teacher and sales agent from Zhob, says, “As we all know, in Balochistan it is very difficult for a girl to come out of her home to earn an income. I was one of the few women from Zhob who has saved 100,000 Pakistan rupees (about $1,200) and set up a vocational training center. We manufacture a range of products, and recently received an order from Karachi!”

The exhibition vividly illustrated the value chain for embellished fabrics by displaying under one roof the various businesses, activities and relationships involved in creating a final product or service. It also promoted interaction between the various

participant groups.

“Just inviting a woman to the dais to speak at an event like this shows how much progress has been made in Balochistan,” says Dr. Fauzia Nazir Marri, a representative of the government of Pakistan.

Adds Syed Abid Rizvi, chair of WESS, “In its own way, the organization is giving birth to a revolution.”

The project, sponsored by FAO Pakistan (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization) with support from USAID, has attracted 2,617 women embellishers and 183 female sales agents in its first year. — Linda Whitmore

Reviews

An antidote to soul-sapping toxins

Taking Your Soul to Work: Overcoming the Nine Dead-

ly Sins of the Workplace. By R. Paul Stevens & Alvin Ung (Eerdmans, 2010, 200 pp. $14 U.S.)

“The workplace is a major arena for the battle of our souls,” say Paul Stevens and Alvin Ung in this latest entry in a growing body of faith/work resources. The good news is that, well, there is Good News: work can be a source of spiritual growth and draw you closer to God.

Stevens has written a number of excellent books on faith and the workplace, among them The Other Six Days and Doing God’s Business. (He has also spoken and led workshops at MEDA conventions.) In his long career as a professor he helped put Regent College (Vancouver) on the map as a leader in marketplace theology. Here he teams up with a much younger man still in the throes of the Monday-Friday work life. Alvin Ung works with Khazanah Nasional, the national investment agency of Malaysia.

Together, in conversational fashion, they mine the wisdom of the Bible and their own rich experiences in global business to redefine the workplace as a venue for spiritual growth.

The book is divided into three sections. First they select nine “deadly sins” of the workplace, the kinds of “soulsapping” toxins most workers face. These are the traditional seven deadly sins (pride, greed, lust, gluttony, anger, sloth and envy) with two more added — restlessness and boredom. These sins “can easily entangle us as we work,” the authors say.

Section two explores nine life-giving resources that function as antidotes, followed by a third section that illustrates nine positive outcomes of integrating spirituality and work.

One might fear that a book on deadly sins would be judgmental. It’s not. This is not a pair of high priests wagging their fingers at sinners. What they do is lay out a map showing some of the mine fields in the workplace, examining them from a number of angles, and showing how they can not only be dismantled but even provide paths to growth. a “rethinking” process that can turn conventional ideas on their head.

Take sloth, for example, which is not merely laziness but can also be manifest in pathological busyness. “Lazy people aren’t the only ones who are slothful,” the authors claim. “Extremely busy people can also be slothful.”

But what are they busy at? People who are morally and spiritually lazy may seem busy but lack big-picture focus, thus they “whittle away at lesser problems while refusing to attend to the most important work at hand.” They may even have workaholic tendencies. Workaholism has its own set of spiritual dangers since “it causes people’s brains to shut down, they have no energy to think about anything other than work — not about relationships, marriage, children, health, parents, church, relationship with God, and especially matters of eternal consequence. They are waiting for life to get less busy; then they’ll put things right.”

The key lies in seeing God’s action in the world. “We are hewing at the roots of sloth when we resolve to be faithful to both great and small tasks,” say Stevens and Ung. Sloth can be overcome with a sabbath consciousness that is more than mere cessation from work but a rhythm that perceives “God’s big view of the meaning of our lives.”

By the authors’ template, this “big picture” includes an important role for peace (“having a passion for completeness and harmony, no matter what the situation”), which they cast as an antidote to boredom (“having insufficient passion or interest to give yourself heartily to work and life”). As they note, the modern corporate workplace, with its cutthroat competition and economic uncertainties, hardly seems like “a sanctuary of peace.” Acknowledging a Christian tendency to simply be nice and avoid conflict, they declare that “insidious patterns of denial, passive-aggressive indirectness, and unspoken resentments” have their own toxicity. Peace does not remove us from those tensions, but plunges us into the center of them, as long as we don’t try to arrive at it “by forcing conformity, ignoring tension, or papering over disagreements.”

Confronting workplace sins and responding with the fruits of the spirit ultimately leads to a recognition that God is in the center of all things — even the workplace — and makes true balance possible.

“I’ve learned that the workplace is a playground for learning to love God and to love people,” says Alvin Ung in one of the numerous dialogues in the book. “Wouldn’t it make a huge difference in my workplace if I made it my goal to find creative ways to love and bless my coworkers, bosses, and staff on a daily basis?”

Pastors might want to shield their parishioners from this book — and then use it as grist for a sermon series. — Wally Kroeker

The sins of which they speak lurk in unsuspecting places, then grow and “produce offspring.”

Greed — “probably the most common workplace sin” — can range from the innocuous to the insidious. “Much of unrecognized greed stems from noble intentions to build a safe and secure financial base for loved ones. Even poor people are not exempt from greed.” Pervasive as it is, greed can be sent running by, for example, regarding shopping as a spiritual discipline, by resisting the wiles of advertising and by cultivating a spirit of generosity, Stevens and Ung suggest.

Lust? It’s not a surprising consequence in a job setting where talented, like-minded people “perform at the top of their game,” all of which contributes to “a subtle yet real eroticism in the workplace.”

Envy? “It is a magnet for other vices. It compounds the effects of other deadly sins.”

With each “sin” the authors guide readers through

Men of God first, chocolatiers second

Chocolate Wars: The 150year Rivalry Between the World’s Greatest Chocolate

Makers. By Deborah Cadbury (Douglas & McIntyre, 2010, 347 pp. $29.95 U.S.)

Often referred to as the “food of the gods,” cocoa has delighted palates for centuries. Less well known is the religious heritage of some historic chocolatiers. In this book, a descendant of the Cadbury family tells the story of the British chocolate dynasties, following their Quaker roots to the eventual recent takeover of Cadbury by Kraft Foods.

“The story of Cadbury, in a way, is the story of a different kind of capitalism,” says Deborah Cadbury, a prolific author and British documentary producer. It is not only the story of her own ancestors but also the story of others who helped bring chocolate to life — the Rowntree and Fry dynasties of England as well as European powerhouses like Lindt and Nestle.

Cocoa, of course, did not begin with these families; its use goes back to the Aztecs. But the diligent work of the British chocolatiers catapulted cocoa beyond a mere beverage into the solid form consumed so widely today.

Mennonites will easily grasp the distinctives (and the social ostracism) of the Quaker spiritual outlook that characterized the rise of the chocolate industry. The England of the 1800s was not especially friendly to the Quakers, Cadbury tells us. Professionally they were outsiders, barred from the universities of the day (Cambridge and Oxford) and from professions like law. As a result, many of them turned to business.

Did they ever. It was Quakers who revolutionized industry by first smelting high-grade iron using coke rather than charcoal. A Quaker established the first passenger train; another invented a new stream of fine China which Josiah Wedgwood would perfect. The founder of Barclays bank was a Quaker.

They also put their own indelible stamp on the way business was conducted.

“The Quaker traders stood apart,” Cadbury writes. “Customers learned to rely on typical Quaker attributes: skilled bookkeeping, integrity, and honesty served up by sober Bible-reading men in plain dark clothes.”

Beyond that, they had an unusual social and religious vision. “As early as 1738, Quakers had a set of specific guidelines for business, empires, men like Joseph Rowntree and George Cadbury were writing “groundbreaking papers on poverty, publishing authoritative studies of the Bible, and campaigning against a multitude of heartrending human rights abuses in a world that seems straight out of Dickens.... As Quakers they shared a vision of social justice and reform: a new world in which the poor and needy would be lifted from the ‘ruin of deprivation’.”

The development and improvement of cocoa as a beverage was seen as a social breakthrough. It was a drink everyone could afford, and it provided a nutritious alternative to alcohol.

Joseph Rowntree, whose company produced the first solid chocolate bar, undertook exhaustive studies of poverty in England, uncovering the complex connections of pauperism, illiteracy, crime and education.

Socially, the Cadbury brothers were pioneers. They hired a staff doctor, eventually adding four nurses and a dentist who offered healthcare services at no charge. They gave out free vitamin supplements, organized fitness training for employees, and established a convalescent home for those who fell ill. They were the first to offer pensions. They set up playgrounds for children, determined that “no child would be brought up where a rose would not grow.”

The Cadbury reforms “helped forge a framework for modern social welfare,” Cadbury writes.

All of this emanated from their religious faith. “George Cadbury’s religious convictions shaped his world,” says Deborah Cadbury. “It unified every aspect of his life and gave purpose and energy to his philanthropy.” For him, the factory was not just a business: “It was a world in miniature. It was a way to improve society.” He believed, simply, that “If everyone followed the teaching of Christ, people and nations could live in peace together.” The British chocolate makers saw themselves as men of God first, chocolatiers second.

They would inspire an American who rose from his Mennonite roots to carve out his own dynasty. He was Milton Hershey, “who took philanthropy to a new all-American scale with the creation of the utopian town of Hershey.”

During the First World War the Cadbury family suffered hostility for their pacifism, and were subjected to intense scrutiny and inspection of company records.

Their social vision persisted to the current century, according to Cadbury. In the waning days of its existence as a family company, before being taken over by Kraft Foods, the company established a “Purple Goes Green” commitment to reduce absolute carbon emissions by 50 percent by 2020. It has sought to ensure ethical sourcing of cocoa (from Ghana, not Ivory Coast which has been accused of cocoa harvest abuses) and provide help to farmers. In 2009 Cadbury launched its leading brand, Dairy Milk, as Fairtrade-certified.

A company official declared: “We were trying to make George Cadbury’s nineteenth-century Quaker principle that ‘Doing good is good for business’ relevant to the twenty-first century. We sought to do this by creating a sustainable supply of highquality cocoa while creating a sustainable life for cocoa farmers.” — WK

which endeavored to apply the teachings of Christ to the workplace,” Cadbury writes. For people like George and Richard Cadbury, business was not an end in itself; it was a means to an end, and that end was deeply spiritual.

“For the Quaker capitalists of the nineteenth century, the idea that wealth creation was for personal gain only would have been offensive,” says Cadbury. “Wealth creation was for the benefit of the workers, the local community, and society at large, as well as the entrepreneurs themselves.”

As they were building their

Soundbites

We’re part of the plan

The kingdom of God is about going out into the fields and doing the work of making the world the way it should be, the way God would have things.... When we see suffering and injustice, it certainly affects us. We may be sad and outraged, but we are not complacent or depressed. We have a plan, and we are part of the plan. The good news that Christians preach is not only that God is going to bring about the world as it should be but also that we are part of that effort. Christians fully believe that we are part of the solution, even as we confess that we are also part of the problem. — Gregory F. Augustine Pierce in A New Way of Seeing

Managing the church

The mission of nonprofits (including churches) is to change lives. The function of management is to make the church more churchlike, not to make the church more businesslike. An organization begins to die the day it begins to be run for the benefit of the insiders and not for the benefit of the outsiders. — Management guru Peter Drucker

Best of times

It may not feel like it in the West, but this is, in many ways, the best of times. Hundreds of millions are climbing out of poverty. The internet gives ordinary people access to information that even the most privileged scholar could not have dreamed of a few years ago. Medical advances are conquering diseases and extending lifespans. For most of human history, only a privileged few have reasonably been able to hope that the future would be better than the present. Today the masses everywhere can. That is surely reason to be optimistic. — The Economist

Trump this

There are few things I hate more than laziness. I work very, very hard and I expect the people who work for me to do the same. If you want to succeed, you cannot relax.... I never take vacations because I can’t handle the time away from my work. I recently read that these days, a high percentage of the people who do take vacations tend to check e-mail and voice mail and call in to the office when they leave. Those are the people I want working for me. — Donald Trump, real estate and TV celebrity

Bank on this

It is the responsibility of the leaders of financial institutions — not their regulators, shareholders or other stakeholders — to create, oversee and imbue their organizations with an enlightened culture based on professionalism and integrity. Through work we all seek to realize ourselves as people, provide for our dependants and make a contribution to the social good achieved through collective endeavor. — Barclays chair Marcus Agius and 16 other bankers in a letter to Financial Times, quoted in Initiatives

Fun@work

One of the advantages of fun in the workplace is that it’s hard to have fun by yourself, you need other people to have the best fun. Fun, then, promotes teamwork and cooperation. Fun is an attitude of playfulness that promotes experimentation and enhances creativity. It creates a sense of vitality and relieves pressures. Fun helps to maintain flexibility in a changing environment. — Workplace fun expert Mel Silberman

What’s in a name

Historically there was a sense that work was God-given and that our identity was tied to it appropriately. Hence in the old world people’s names were tied to their work skill — Miller, Baker, Carpenter, Hufnagle (horseshoer), Kowolski (blacksmith). — Pete Hammond

Frantic sloth

Slothful people may be very busy people. They are people who ... fly on automatic pilot. Like somebody with a bad

head cold, they have mostly lost their sense of taste and smell. They know something’s wrong with them, but not wrong enough to do anything about it. — Frederick Buechner

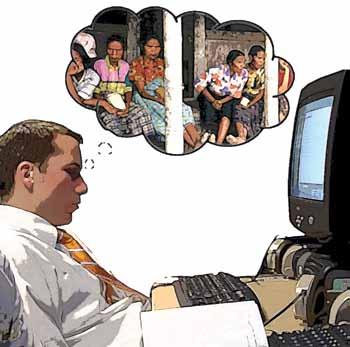

Office tai chi

The first sign of restlessness at work occurs when we carry out our tasks half-heartedly — though we might be present in body, we are absent in spirit. Gradually we begin to abdicate our responsibilities, justifying this by saying they are really other people’s work. We learn the art of office tai chi, using our hands and feet to ward off assignments headed our way and diverting work to other people’s desks. Perversely, even as we become lackadaisical workers, we fantasize about how we could be doing great things for God in some faraway place, like helping missionaries haul medical supplies into the hilly regions of Sulawesi for suffering villagers. — R. Paul Stevens and Alvin Ung in Taking Your Soul to Work

Gandhi’s test

Whenever you are in doubt, apply the following test: Recall the face of the poorest and weakest person you may have seen and ask yourself if the step you contemplate is going to be of any use to them. — Mahatma Gandhi

Letters

History alive

Enjoyed your piece on “Why I started my own business,” by Jean Kilheffer Hess (Nov/Dec 2010 issue). I was amused by her conversation that no one had ever heard of the oral history services she provided. We have more than 500 members, most of whom said the same thing, before they discovered the Association of Personal Historians. We’re a new profession, made possible by digital technologies that make customized publishing and multimedia productions affordable to small businesses. People who want to do what Jean Hess is doing join the Association of Personal Historians to learn from each other about the best ways to create personal histories and to start and grow businesses that feed their souls.

Thank you and Ms. Hess for helping to spread the word about the movement to record, document, and share lives for coming generations. — Nancy Heifferon, San Jose, Calif., marketing director, Association of Personal Historians

We’re not alone

A thank-you again for producing The Marketplace. It’s one journal I read pretty thoroughly. I found interesting your claim to near exclusivity to the acronym MEDA (January/February issue). I checked the name on www.acronymfinder.com and found quite a few more. See below. • Mission Economic Development Association (San Francisco) • Maintenance Error Decision Aid (Boeing) • Massachusetts Eating Disorder Association, Inc. • Molecular Electronics Design Automation • MicroEnterprise Development Association • Metro Economic Development Alliance (Jackson, Miss.) • Mobile Environmental Data Acquisition — Ray Martin, Executive Director, Christian Connections for International Health, McLean, Virginia