30 minute read

Soul enterprise

Giving money is hard work

“I hope you don’t get your wish.”

That’s what a wealthy businessman said to me after I told him I wished I was like him — rich enough to give away lots of money.

He made the comment as we visited a development project he had funded, taking a look at what his generous donation had been able to accomplish.

Now, why would he say that? After all, what could be better than to be wealthy enough to support various good works?

“Giving away money is hard work,” he said. “You may spend the rest of your life working on how to give it in a meaningful and caring way.”

I think many wealthy people who support worthy causes could say the same thing. While most of us feel besieged by the number of requests we get for money, it’s nothing compared to the number of letters that cross the desk of many businesspeople every month. What makes it even harder is that some of the requests come from friends or fellow church members, making it even harder to say no.

Plus, there’s the effect that having money to give can have on your relationships.

“Sometimes you feel that the way people see you has changed,” my businessman friend said. “It’s almost like they don’t see you as a friend or as a member of their church, but rather as a source of money.”

Then there’s the whole business of saying “no.” It’s hard to tell people you go to church with that you won’t support their worthy project, he said. Plus, there’s the worry about what people will think if he declines to provide support. If he says no to the mission board, will people think he is anti-mission? Ditto for the women’s shelter, the town library, the local Christian school. “I’d like to help them all, but I can’t,” he said.

And sometimes he really can’t — he doesn’t have the funds. “I may be worth a lot of money, but it isn’t all cash,” he said. “It’s tied up in the business or investments.” And even when he says “later,” there are times when he can’t fulfill his promise — an investment may do poorly, or a part of his business may fail.

In an effort to guide his giving, he and his wife are setting up a family foundation to direct his support to a few areas. As well, they took a philanthropy workshop to learn how to be better givers. Through it they learned how to choose good projects to support and how to give in ways that create real change for the issues they care about.

Through the workshop he learned that “good philanthropy takes work, a lot of research, knowledge about who you are giving money to and a willingness to get involved enough to be part of the struggle for change,” he said.

Without that kind of commitment, he said, it’s just “checkbook philanthropy, and that is often no more than throwing money at problems.”

I still dream of being able to give away large amounts of money for worthwhile causes. But maybe, like my friend said, I should be careful about what I wish for. — John Longhurst

God’s ROI

In business we often measure our performance by rate of return on investment (ROI). We examine our earnings as a percent of our total assets. Or we use an investment base of equity plus long-term debt.

I like to think of God as a capitalist (small c) who has invested heavily in you and me. God equips us. We are part of his endowment fund. And I believe he expects to get a good return on his investment.

When God audits my performance, I wonder how he will measure ROI. Will it be by the way I have treated my partners and employees? By my loving service? By the amount of integrity that has gotten to the bottom line? By the methods I have used to collect overdue accounts? By the ways I have used power?

Maybe we ought to begin each day with a prayer like this: “O Lord, I am your investment fund. You are my investment manager. Help me today to produce a good yield on all the assets you have credited to my account. May you be pleased with the rate of return on your investment in me. Forgive me when my short-term performance is a big zero, or worse yet, a horrible deficit. Don’t purge me from your portfolio, but lift me to higher ground. Amen.” — John H. Rudy in Moneywise Meditations: To Be Found Faithful in God’s Audit (Herald Press)

Waiting for leverage

A large city was getting second-rate architecture in its public buildings — its schools and the like. Architects were being chosen for having the right connections. Dave and his colleagues, members of the local chapter of the American Institute of Architects, were ready to change the “good old boy” selection process to one that assured better architects for better public buildings.

Dave took his concern to his father who advised, “Don’t give up. Just wait until you are in charge.” He did. He became head of the local chapter of the AIA. He found the “leverage” needed to fix the problem. It came from the members of the chapter who were ready to back him and from a key supporter on the city council. They drafted a proposal for selection of architects based solely on their qualifications. The best architects got the commissions for design excellence and the public got better schools for better education of the city’s children.

When he heard of the story, Dave’s bishop said, “You are fortunate to be involved in a profession that improves the quality of life.” Those words sustained him in some hard times still ahead. — Member Mission Network

Work prayer

Dear God, I beg You to change my heart about work. Take my joylessness away, and show me the awesome opportunity that I have right now to glorify You in the mundane. — Attorney Kevin Williams Overheard: “

Disconnect

“Recently, I conducted a research survey at a large church in the southeastern U.S. The results showed that 74 percent of the respondents saw little to no connection between their faith and their job. Of those who saw a connection, 64 percent were employees of a religious institution. Only 11 percent of respondents with a job in a nonreligious organization saw a connection between their faith and their employment. Furthermore, even those 11 percent reported a lack of confidence and fulfilment in their ability to integrate their faith at work.” — Mark L. Russell in The Missional Entrepreneur: Principles and Practices for Business as Mission

“Grow into your ideals, so life can never rob you of them.” — Albert Schweitzer

Fun in the past

Erie Sauder had a vision for hands-on history — the bone and sinew of pioneer life

Debbie Sauder David looks out of her secondfloor window at the circle of restored pioneer shops below. The first of several hundred tourists are starting to trickle into Sauder Village, eager for a trip into the recreated past. They’ll stroll in and out of historic homes and community buildings, watch tinsmiths and weavers at work, enjoy hand-dipped ice cream, take a ride on a miniature train, and immerse themselves in a faithful recreation of life as it used to be. Throughout the day Debbie, executive director, will tend to life as it is now — administering a thriving business where history is swaddled in the reality of finances, customer service and a work force of 450 employees and 600 volunteers. Like anyone in business, she will keep an eye on all the things that make an enterprise sustainable.

She’ll keep another eye on a legacy — handed down by her grandfather, Erie Sauder. That legacy is never far from view. She occupies his old office in the Welcome Center of Sauder Village, one of Ohio’s leading tourist attractions. When she looks out the window, the first thing she sees is the original shop where a teenaged Erie honed the skills that would produce Sauder Woodworking on the other side of the town of Archbold. When things get tough, as they are prone to do in business, she can recall her grandfather’s oft-quoted observation — “It’s amazing what you can do when you don’t know it can’t be done.”

By his own description, Erie Sauder (1904-1997) never had much taste for formal education and didn’t get past eighth grade. His gifts lay elsewhere, as the furniture world would see.

Brilliantly innovative, he built a complicated lathe while still in his teens. In 1934, with a stake of $38, he started his own woodworking company. When it burned down two years later, he rebuilt. Another devastating fire came in 1945. Erie discovered to his despair that his insurance coverage had not kept up with the company’s growth.

“I was broke,” he said many years later in a video interview.

Local folk pressed him to rebuild again, and within a year he was back in business. Sauder Woodworking would become the largest producer of ready-to-assemble (RTA) furniture in the United States.

Visitors came in droves to see his manufacturing marvel.

“We had children go through the factory, busload after busload,” said Erie, who often accompanied the youngsters through the plant.

One day something caught his attention. An employee set the controls on an automated cutting machine and turned around to chat with the children. It struck Erie that the automation might mislead youngsters to think life was as easy as pushing a button.

“It was as if no one had to work,” said Erie, “and that’s not the way life is.”

He decided to tell the “real story” so future generations would understand and remember. Thus was planted the seed that grew into Sauder Village.

The Village opened in 1976, when Erie was 72. By then he had stepped back from day-to-day corporate management, and his travels to Paraguay to establish MEDA were behind him. The Village became his retirement passion.

“He wanted it to be a tangible experience for visitors,” says Debbie. “He wanted people to be able to touch things. He was far ahead of his time, because today museums everywhere are talking about hands-on experiences.”

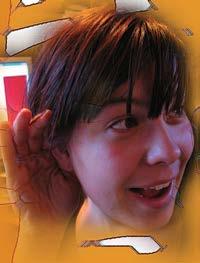

Debbie Sauder David in the Village “circle,” with her grandfather’s original farm shop in the background.

Erie’s vision was to recreate pioneer life and offer future generations an authentic encounter with his own ancestors who had come from Europe to tame the Great Black Swamp of northwestern Ohio.

“You can put it in history books,” he said, “but it will never talk like this tangible history will.”

Today, Sauder Village is Ohio’s largest living

history museum, drawing 1,500 visitors a day in high season. Dozens of restored buildings depict the bone-andsinew of pioneer life. Period shops of spinners, woodworkers, coopers and merchants convey the economic, cultural and religious life of early Ohio.

Retail shops feature quilts, crafts and artifacts, and appetites of any size can be satisfied at The Doughbox Bakery and The Barn restaurant. There’s also a 98-room Sauder Heritage Inn and campground, a fishing pond (aptly named Little Lake Erie), Founder’s Hall conference center and an outlet store offering ready-to-assemble furniture from the factory across town. The newest initiative, Pioneer Settlement, opened August 22, 2009, 175 years to the day after the first permanent European immigrants arrived. Back then, northwest Ohio was a swampy wasteland, full of mosquitoes, bears and wolves. The newcomers came with ox carts over corduroy roads made of cut logs. Over the years they drained the swamps, producing some of the richest farmland around.

The settlement shows it all through living vignettes. The “walk through time” begins with authentic Native American wigwams, heirloom gardens, and a trading post where beaver pelts were the gold standard of the day.

A subtext, bred in the bone of Erie’s vision, is the importance of hard work, diligence and entrepreneurship. Like pioneers everywhere, whether in Czarist Russia or Paraguay, these Mennonite forbears had to work and sweat. And Erie wanted people to know it.

Learning about it, however, does not have to be a chore. “Grandpa wanted people to have fun,” Debbie says, noting that the corporate mission strives for an experience “rich in history, hospitality, creativity and fun.”

The fun doesn’t apply only to guests. Staff can be seen smiling and whistling as they show up in the morning. “Junior historians” help “play the game” by joining costumed interpreters to churn butter, make pies and engage guests. Over a season there will be 230 of them, ages 10 to 16, from 50 surrounding communities. They come as volunteers, work three-hour shifts, and receive free lunch, treats and free family admission. More than half come from home schools, which recognize the service as part of their training. They learn skills in employment, hospitality, reliability and customer service. “We’re creating the next generation of volunteerism,” says Debbie.

At the other end of the age spectrum are retired folks. “Some of our finest wood craftsmen are in their mid-80s,” she says. “Other crafts workers and costumed guides are in their 90s.”

Debbie presides over it all with flair and spright-

ly devotion. Like her grandfather, she wears multiple hats, functioning as a determined executive whose skill set includes administrator, planner, employer, crisis manager, therapist and jack-of-all-needs.

She is the daughter of Erie’s son Maynard Sauder, and wife of David David, pastor of the local United Methodist

Claire Graber, a Native American interpreter, cooks a batch of beets and greens grown in the heirloom garden in Pioneer Settlement. She is a great-granddaughter of Erie Sauder.

Church. She returned “home” after a distinguished career as a specialist in traumatic brain injury in California and Texas. Her patients were people who had suffered accidents or gunshot wounds to the head, were unconscious or in a coma, and needed to be brought back from the edge of death to functional life. It was Debbie’s task to devise a strategic recovery plan for each patient and work with employers and families to help them integrate back into school and work settings. “I worked with high level executives, engineers, factory workers, teachers, kids, football players, criminals and all kinds of people who had a rough background,” she says.

“Through that work I had a very tangible sense of service. I was essentially holding people’s hand at their point of crisis, getting them back to being functional, produc-

tive citizens.”

People who had been in a coma would tell her later, “Yours was the voice I heard — like an angel.”

She became a sought-after speaker on traumatic brain injury, worked her way into administration, and became an expert in integrating healthcare systems. In Texas, she served on a statewide advisory board for traumatic brain injury.

In 2000, three years after Erie Sauder died, Debbie and her family had an opportunity to return to Archbold. She had resisted earlier invitations to work in the Sauder enterprise, but when her husband was offered a pastorate near her hometown, and with her daughter entering high school, the time seemed right. So she returned to carry on her grandfather’s vision.

Her previous career may not be the usual path to corporate success, but Debbie sees deeper connections. People sometimes ask if she misses her work with patients and healthcare.

“I’m taking it to a different level,” she says. “It’s still customer service. It’s still client satisfaction. It’s still education in multi-sensory ways. Many write back It’s still relationships, building people and nurturing a to say “this was good team. It’s still leadership. It’s still community ina healing place volvement. It’s still service.” In fact, she adds, it for my soul” shares common ground with MEDA, on whose board she serves as vice-chair. “All these things are very similar to what MEDA is doing — going alongside and coaching, laying out a strategy for them, helping clients to become independent people who can care for their families and contribute to their community and church.”

She feels keenly the responsibility of generational stewardship, which can loom large in a town dominated by a family company. Being a Sauder in leadership gives a grounding not only to the Village staff but also to the larger community, she says.

“To have a third generation person who is caring about my grandfather’s place and making it a community and regional resource, building networks with other arts, cultural and educational organizations in the region, I think that gives a sense of comfort and stability because our name’s on the door. It’s not ours — it’s a public charity — but it’s ours to be a steward of.”

And that means serving the community in numerous ways, not the least of which is by being a stimulus to draw people to the area. “How many people would get off the turnpike at Exit 25 if it wasn’t for Sauder Village,” she muses. “And what does that mean to the community?”

If she ever gets bogged down with the nuts

Courtney Krieger, pictured with Shellee Murcko, costumed interpreter, is a “junior historian” who helps “play the game.” They are on their way to bake peach cream pies on an outdoor oven.

and bolts of finances, employee issues and concerns about keeping the place sustainable, Debbie can take a stroll outside to remind herself that employees love coming to work and people are happy.

Beyond the kids licking ice cream cones or hopping on the train, their eyes widening as they pass by a team of big oxen, she sees people not only having a lot of fun but also learning in spite of themselves and creating family memories.

“How many times in today’s society can you have an authentic experience that’s tangible?” she asks. “At a time when many kids are so preoccupied with Game Boys, texting and MP3s that they don’t even interact with real people, we’re offering a non-digital environment that slows down the pace and allows reflection and creative thinking.”

Of the 100,000 guests who pass through the gates every year, many write back to say “this was a healing place for my soul,” or a respite in a time of need, because it allowed them to work through troubles in a refreshed and renewed way.

“You know, when you’re disappointed by your leaders, or when your role models don’t have the right stuff, it’s important for kids to learn values,” Debbie says. “When people put their life in perspective, and see how hard people worked, and the sacrifices they made to create a better life for their children, you realize they didn’t just kick back and have the easy life. They built churches, they built schools, they contributed to the future of their community.”

No wonder, then, that Debbie sees Sauder Village, with all its layers of history, fun and entrepreneurship, as another form of service.

No doubt Grandpa Erie would agree. ◆

A legacy continues

As a child growing up, Dan Sauder heard many stories about Paraguay from his grandfather, Erie Sauder. Erie was on the ground floor of MEDA’s first projects in the early 1950s. Over the years he visited 18 times, and fondly described his work there as the most satisfying of anything he did.

“But it had never really sunk in,” Dan says.

One day in 1997 Dan dropped in to see his ailing grandfather, then near the end of his life, and found him entertaining visitors. One of them was Kornelius Walde, a prominent Paraguayan Mennonite entrepreneur with whom Erie had worked closely.

“Walde had brought along two of his sons,” Dan recalls. “He said he wanted them to meet Erie and see how you can be a Christian in business, how you can be both honest and successful.”

Walde proceeded to relate one story after another about Erie Sauder’s work with the Mennonite colonies and indigenous people in Paraguay.

“When Walde laid out the whole story of my grandfather’s involvement, it finally clicked,” says Dan. “I could connect all the stories. I was fascinated by it all.”

In the days after that visit Erie Sauder declined

quickly. He would lose consciousness, then rally back.

His former pastor said to him, “Erie, you keep hanging on. Is there something you still want to do?”

“Yes,” Erie said. “I want to talk to the third generation.”

Dan and two cousins hurried over. Their grandfather had one last request. He told them, “I just want to hear from you that you’ll be fair and honest in the business.”

They assured him that they would.

“I told him,” says Dan, “that it had been great to meet the Waldes and to hear the eyewitness accounts. I said I was proud of all he had done, and that I wanted to see it for myself. I said, ‘I promise that I will try to go to Paraguay and see the work that you have done there’.”

It was the last time he saw his grandfather alive.

A few years later Dan Sauder had a chance to

make good on his promise. Co-worker John Yoder, who was then on the MEDA board, alerted him that MEDA was planning a tour to Paraguay in 2001.

That was his chance to experience the country. So

Dan Sauder in his office, with a picture of his grandfather’s original farm shop behind him, and a photo of Erie Sauder at lower right.

he went, with his wife, father Myrl and mother Frieda. Together they retraced Erie’s steps, visiting, among other things, the Fortuna Shoe Factory in Filadelfia, which was MEDA’s third project. They visited Mennonite colony leader Heinrich Duerksen. “Erie and Heinrich worked together a lot,” says Dan. “They were like peas in a pod. Our timing was great, because Heinrich died six months later.”

Dan isn’t sure who enjoyed it more, he or his father Myrl, who had never been there before. “He was like a kid in a candy shop,” Dan says.

Today Dan Sauder continues to live his

grandfather’s legacy — in business and in life. He is vicepresident of engineering at the company his grandfather started, Sauder Woodworking Co. In this capacity he oversees designing and building machinery to make furniture, and also looks after product engineering.

It’s still very much a family operation, now solidly in the hands of the third generation. And it is still the largest ready-to-assemble (RTA) furniture manufacturer in North America, with products prominent at Wal-Mart, Target and Office Depot.

The company produces 700 different items, from beds to desks. Every year 150 new products are introduced. Sales and design people come up with new concepts, and Dan figures out how to make them. A lot of effort goes into a continual discernment process — how to pick winners, how to sort out what fits best into their competencies.

Recent economic disruptions have not bypassed the Sauders, whose He needed to visit work force has shrunk from 3,000 to 1,600 Paraguay, and see today, mostly by attrition. They’ve branched for himself what into other products to reduce their reliance his grandfather on RTA. One of them is caskets to meet a had done growing demand for reasonably priced funerals. “It’s a traditional business, hard to break into, but in the past few months we’ve gone from selling one a week to one a day,” Dan says. Other new products have been wood track ceilings that homeowners can click into place, and tension-fit locker shelves for schools.

Dan also carries on the MEDA tradition, which

defined his grandfather’s life for many years. Dan is currently chair of the Northwest Ohio MEDA Chapter (see following story).

His grandfather’s example looms over this and other aspects of his faith/business witness. A leadership program he’s involved in is based heavily on the model set by Erie. “My section is called Living by Example,” says Dan. “I tell the story of Erie on his deathbed, and the concern he had for integrity and conscientiousness. Integrity was his dying wish. He valued hard work, taking ownership, not giving up. I talk about the excuses people give.” Erie Sauder had plenty of reasons to make excuses if things went wrong. He had been born two months premature, so small he had to drink milk by sucking it from a rag. He was put in a shoebox behind the stove. The doctor said, “Don’t tell his mother, but he’s not going to make it.” He survived, and lived through the Depression to start Sauder Woodworking. It burned down twice (see previous article) and literally rose from ashes each time. Plenty of other setbacks could have been used as excuses. But Erie didn’t believe in excuses. Even the work in Paraguay shouldn’t have worked, with all its travel, ranging from commercial aircraft to bush planes to buggies in the jungle, Dan muses. And yet it did. “He often said that the work with the Indians was the best he ever did,” he says. “The message from Erie that I try to convey is that happiness does not come from wealth, it comes from helping others. Your satisfaction in life is from serving others. That was a great witness to me.” ◆

On a path to help the poor

New campus-based ASSETS emerges in Ohio

When Jill Wade moved to northwest Ohio she brought along a healthy supply of energy for the poor. By all accounts, she is the powerhouse behind a new program to equip fledgling entrepreneurs to succeed in business.

The program is a replication of the ASSETS model which MEDA launched in 1993. ASSETS has since been unhooked from MEDA, but lives on as an instrument local groups can use to alleviate poverty.

Wade first heard about ASSETS when she moved to Ohio after a long corporate career.

She asked her new neighbors, “Who around here has a passion for the poor?” They referred her to Dan Sauder, chair of the Northwest Ohio MEDA Chapter, and Frank Ulrich, who had been one of the heavy-lifters behind Toledo ASSETS, which was launched in 1999.

The two men took Wade to Toledo to see the program that over the years has trained 786 graduates who in turn started 230 businesses and reinforced 200 more. After hearing the stories of changed lives as low-income people struggled for self-sufficiency, Wade says, “I was entranced. I really wanted to get involved in something to help small businesses.”

Rather than duplicate Toledo ASSETS, Wade

chose to fashion something specific to the northwest region. She felt a new ASSETS would work best as a partnership.

She contacted the president of Northwest State Community College, which serves 5,000 students from five counties around Archbold. A collaboration was forged and a new program was born.

ASSETS is run on campus, with accredited classes open to enrolled college students as well as to community

folk who want to start or expand a business.

The first class last fall was small, but by spring semester 22 people had enrolled, a third of whom were traditional college students.

Cost of the course is $325, but scholarships are available. Wade receives a teaching fee from the college but turns it over to ASSETS.

The class meets every Friday for 13 weeks, teaching business skills to entrepreneurs to provide meaningful employment for themselves and those they hire. It has already resulted in the “The need here is launch of several new businesses and the reingreat; people are forcement of numerous others. going hungry.” The textbook is “Planning the Entrepreneurial Venture,” produced by the Kauffman Foundation. Students can download it free, along with additional web-based resources.

The curriculum is basically about developing a business plan, says Wade. Each week has a different topic, but at the end a workable business plan must be produced.

Lessons are augmented by class presentations. A CPA explains finances, another talks about accounting software. Dan Sauder visits each semester to discuss product strategy; two local painters describe what it’s like to be both competitors and collaborators. An attorney teaches basic contract law, and a human resources specialist deals with hiring and firing.

All participants who complete the course receive three units of college credit. For those already enrolled in college, the units are simply added to their transcript.

A wide range of skill sets is evident, says Wade.

One student, for example, was essentially illiterate, though highly intelligent and motivated. Unemployed, he wanted to set up a remodelling business utilizing his construction skills. He had an interest in old homes and discerned a niche for remodelling Victorian houses. By the end, he had done enough market research to devise a solid business plan.

Another student was so poor he struggled to get gas money to come to class. His phone and electricity had been cut off. He failed the first course, but took it again and passed. “By the second semester he was understanding the real world, and we watched him go from pipe dreams to a functioning business,” says Wade.

Several students already had small enterprises up and running. Some had hobby businesses, like one who enjoyed framing pictures and hoped to grow it into a livelihood. Almost all brought a business concept they were struggling with.

One who had a small retail store picked up new skills in demographics and decided to rethink his product selection and niche.

Another wanted to open a lawn care business. “He thought he would just buy a lawn mower and get to work,” Wade recalls. “While going through the class he had a bit of an awakening. He told the class he realized he wouldn’t make it on $20 to $30 a lawn, and that it would work better as a side business.”

Then there was the student who had discovered there were no bilingual daycares in the area. She decided to establish a Spanish/English daycare center for this unique niche.

Wade believes northwest Ohio, where unemployment is 14 percent, is ripe for a self-employment program like ASSETS.

“The need here is as great as in places overseas,” she says. “People are going hungry here.”

The calmer pace of northwestern Ohio is a

big change for Wade after a 40-year corporate career in strategic marketing, economic analysis and risk management for major insurance and telecom companies. The adrenalin rush of big business is more than eclipsed by her passion to address local poverty. She sees a providential hand at work in her life. “We were on a path to become Mennonite,” she says. “God picked us up and put us here.” By her account, she and her husband “kept being drawn to the Mennonites.” While living in Chicago they drove Jill Wade: “We were on a path to become Mennonite.” down to northern Indiana and visited Shipshewana where they discovered the Menno-Hof, a Mennonite and Amish information center. They found the beliefs presented there compelling, and “went corner to corner.” They met a Mennonite couple there and ended up going to church with them. Wade kept doing research online about this group she found so fascinating.

They decided to pick up stakes and move to Stryker, a few miles from Archbold. Happily, her consulting work could be done from anywhere. She and her husband found a property in Stryker, moved two years ago, and were baptized into Zion Mennonite Church in Archbold.

“We really felt led,” she says. “We have been just picked up and carried.”

Dan Sauder may be inclined to agree, at least as far as ASSETS is concerned.

“It wouldn’t happen without her,” he says. ◆

Morocco’s youth make strides

Survey shows YouthInvest clients find jobs, earn and save more

The initial verdict is in — young people in Morocco show sharply giving youth confidence to knock on employers’ doors, even for part-time work, and some are improved financial literacy putting into practice the after their first full year entrepreneurial skills they with MEDA’s YouthInvest learn from the training. program. What’s more, average

Many more of them income has increased by have found jobs and are 15 percent among those earning more; almost all who are employed.” have opened savings ac- 3. Youth are now counts, says Leah Kater- better prepared to enter berg, MEDA’s program the workforce through manager for monitoring strengthened personal and project evaluation. and professional devel-

The five-year $5 opment. Eighty percent million program, spon- reported better attisored primarily by The MasterCard Foundation, got underway in 2009 to MEDA’s program “helped me a lot,” says Mohamed Lamrani, who runs an appliance repair shop in a village in eastern Morocco. Besides basic budgeting, it taught him the value tudes and outlook on life. “Improvements in personal, financial and boost employment for an of advertising. “Now, I place samples of materials to repair business skills provided exploding global youth outside my shop,” he says, “and I have made an advertising by the training have been population. It aims to im- poster which I hang outside, on the door of the store. The noted by family members, prove financial literacy and advertising has had a large impact on people.” friends and employers,” entrepreneurship among Katerberg says. young people in Morocco and Egypt by teaching business Among the majority who have opened savings acfundamentals and smoothing access to financial services counts, 28 percent said they planned to use the money to that have been out of their reach. start a business or improve an existing business. Another

Katerberg says a survey at the end of the first full year 17 percent planned to purchase equipment for their shows positive results among the 2,184 youth (51 percent business. Others said they hoped to use the money for female, 49 percent male; average age 20 years) who have education, emergencies or to finance an event such as a signed on to the program so far. A random survey of 157 wedding. youth clients showed the following: Respondents said the program has helped them with 1. Youth are beginning to grasp the importance of accounting, marketing, customer relations, savings and saving: 96 percent of youth clients now save, compared credit, personal skills, and understanding how to start a to 19 percent before entering the program. “They have business. begun to set goals for themselves and are using their sav- Mastering these skills will help young people (who ings accounts to plan for achieving them,” says Kater- account for 37 percent of Morocco’s unemployed) create berg. their own opportunities in the job market. 2. Employment and income have risen: 25 percent of “Youth are overwhelmingly satisfied with the content them now work, nearly double the 13 percent at time of of the training and the effectiveness of the trainers,” says registration. A third of the new jobs come from self-em- Katerberg. “All said they would recommend the program ployment. “We didn’t expect to see a large percentage to a friend or family member.” of the youth working at this early stage in the program, YouthInvest plans to eventually equip 50,000 young as many are still in school,” notes Katerberg. “Such a people in Morocco and Egypt with greater access to savpositive shift in one year shows us that the program is ings and credit, increased incomes and wider skill sets. ◆