41 minute read

Soul enterprise

Biblical billionaire

Forty years ago David Green started making miniature picture frames in his living room. That modest enterprise blossomed into today’s Hobby Lobby, a $3 billiona-year arts and crafts emporium with 22,000 employees in 520 superstores in 42 states.

Nothing like that grows without a fair bit of savvy and hard work, but Green, 70, takes no credit. “If you have anything or if I have anything, it’s because it’s been given to us by our Creator,” he says in a lengthy profile in Forbes magazine. “So I have learned to say, ‘Look, this is yours, God. It’s all yours. I’m going to give it to you.’ ”

That apparently is no idle pledge. Forbes, which ranks Green 79th on its list of the 400 richest Americans, with a net worth of $4.5 billion, says half of Hobby Lobby’s pretax earnings go to evangelical ministries that fit Green’s conservative focus. With lifetime giving estimated at more than $500 million, the magazine calls him “the largest individual donor to evangelical causes in America.”

“I don’t care if you’re in business or out of business, God owns it,” Green is quoted as saying. “How do I separate it? Well, it’s God’s in church and it’s mine here? I have purpose in church, but I don’t have purpose over here? You can’t have a belief system on Sunday and not live it the other six days.”

Green’s giving focuses on colleges, churches and ministries that pass his tight doctrinal test. None others need apply. He also likes to share Scripture and reportedly has backstopped the distribution of 1.4 billion pieces of gospel literature in more than a hundred countries. A mobile Bible app he sponsored boasts upward of 50 million downloads.

According to Forbes, Hobby Lobby stores are closed Sundays so employees can go to church. Four chaplains are on the payroll, and the company headquarters provides a free health clinic. “Green has raised the minimum wage for full-time employees a dollar each year since 2009 — bringing it up to $13 an hour — and doesn’t expect to slow down. From his perspective, it’s only natural: ‘God tells us to go forth into the world and teach the Gospel to every creature. He doesn’t say skim from your employees to do that’.”

Green has taken steps to guard his spiritual vision if the company is sold or dissolved — 90% will go to ministries and the rest into a trust for family members. He knows his company won’t last forever. “Woolworth’s is gone,” he told Forbes. “Sears is almost gone. TG&Y is gone. So what? This is worth billions of dollars. So what? Is that the end of life, making more money and building something? For me, I want to know that I have affected people for eternity.”

What would you do?

Being a conscientious objector can mean more than resisting military service, like not working in a military-related company. Many Christians also wouldn’t want to work for a casino or a massage parlor. Some investors won’t buy military, tobacco or environmentally destructive stocks.

What if you own a construction company and you’re invited to bid on a job that you deem morally problematic? Or you find out after you’ve started who you’re actually working for?

Tim found himself in this position. As reported in World magazine, his concrete company was busy pouring concrete for a building being put up by a general contractor who was one of his best customers. Then Tim discovered that the building, initially described in vague terms, was going to house an enterprise that conflicted with his morals. His wife said, “Now that you know, how can you pour one more drop of concrete?”

Tim decided to pull out, and removed his crew from the site. Several other subcontractors who shared his ethical qualms followed his example. The project was significantly delayed.

Tim braced for consequences, but as it turned out he was not sued and even got paid for the work he had started. Word got out, and Tim even received some new business because of his stand.

If you were in Tim’s position, what would you have done? So far we have not mentioned what kind of a building it was, so not everyone might agree with him. We will say it was one of the following: a casino; a company that manufactures military components; a medical facility to perform late-term abortions; a liquor distribution warehouse.

Depending on which one it was, would you have made the same decision?

Slow down, be ethical

Has life in the corporate lane gotten too fast, what with instantaneous share trading, 24-hour news, just-in-time delivery and the immediacy of tweets? Think, too, of all the corporate effort that goes into policing time to make sure none of it is wasted.

The Economist asks: Is it wise to be so obsessed with speed? Is it so bad to take one’s time? The magazine notes that the pre-flight checklists used by pilots help slow them down and make them more methodical. It quotes famed investor Warren Buffet, who likes to hold stocks rather than churn them, as claiming that “lethargy bordering on sloth remains the cornerstone of our investment style.”

Slowing down can also make us more ethical, according to management research quoted by the magazine. “When confronted with a clear choice between right and wrong, people are five times more likely to do the right thing if they have time to think about it than if they are forced to make a snap decision. Organisations with a ‘fast pulse’... are more likely to suffer from ethical problems than those that move more slowly.” The researchers suggest companies use more “cooling-off periods” or require several levels of approval for important decisions.

Why fewer are hungry

“Food pantries are important, but they’re not the reason far fewer of us go hungry today than ever before,” according to Brian Brenberg, a business and economics professor at The King’s College, New York City. In his view, the real reason is because of jobs that have nothing directly to do with handing out food.

“Fewer go hungry today because some of us lend money to farmers so they can buy new tractors,” he writes in World magazine. “Fewer go hungry today because some of us design even better tractors, or tinker in workshops to keep the old ones running. Fewer go hungry today because some of us look at spreadsheets to figure out how companies could spend less money on tractors and produce even more food.

“Jesus told us to feed the hungry. That’s what bankers, engineers, mechanics, and consultants do every day.... We live in a world where many people, often unknown to one another and devoted to all sorts of specialized tasks, work together in vast networks to feed and clothe and heal in ways nobody ever thought possible. When we participate in one of these networks — however remote our job may be from the hand that administers the bread or medicine — we help to fulfill God’s creation mandate.” “The idea that service to God should have only to do with a church altar, singing, reading, sacrifice and the like is without doubt the worst trick of the devil. How could the devil have led us more effectively astray than by the narrow conception that service to God takes place only in church and by works done therein.” — Martin Luther

Overheard

“I’m prepared to contend that the primary location for spiritual formation is the workplace.” — Eugene Petersen in Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places

Flowing with milk and honey

MEDA’s second-largest project aims to give 75,000 Pakistanis a livelihood boost

Reheman dips a ladle into a large metal can to lift out a sample of fresh milk. Using her new testing kit, she’ll gauge fat content and check for impurities. Higher fat content will earn a premium from the commercial buyers. Any impurities she finds will likely be the result of a middleman along the way who tried to inflate yields by adding water (possibly contaminated) or other crude additives to improve the milk solids.

Reheman recently completed a 10-day training program on milk testing and record-keeping, qualifying her as an authorized female village milk collector (FVMC). In a short time she has grown from zero income to having a client base of 20 livestock owners who bring her 70 liters a day. Now she earns $35 a month.

Reheman is one of thousands of “success stories” in MEDA’s Entrepreneurs project in Pakistan, the secondlargest project MEDA has undertaken internationally (the largest has been a mosquito net project in Tanzania). Funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the $30 million five-year project (2009 to 2014) aims to increase the incomes of 75,000 women micro-entrepreneurs in remote areas of the country, many of whom work within the confines of their homes, through improved production techniques, higher quality and more competitive products, and access to better markets. The project works in four key value chains with high potential for profitability and market expansion: dairy, embellished fabrics, medical and aromatic plants, and honey production.

The project builds on foundations laid down in earlier

Vast numbers of rural dwellers (mostly women) are involved in small-scale milk production. Livestock and dairy account for half of Pakistan’s GDP and more than 40 percent of its employment.

MEDA projects. Utilizing the value-chain methodology that has come to define many MEDA projects around the world, the project relies heavily on local partner organizations that are investing in the country. “Over the years MEDA has developed the strategic ability to mobilize local partners, and that has given us a strong foundation in Pakistan,” says Suzi Slomback, MEDA’s Washington-based project manager. “The Entrepreneurs project is working with eight local partners on the ground, with another coming on board by the end of the year.” Half-way through the scheduled timeline, Entrepreneurs has already reached 40,000 clients.

Dairy — 21,000 clients

Livestock and dairy account for half of Pakistan’s agricultural GDP and more than 40 percent of its employ-

ment. Vast numbers of rural dwellers (mostly women) are involved in small-scale milk production (one to three animals). The project aims to link 21,000 of them with markets, access to veterinary service providers, better feed and supplements, nutritional information, disease management/prevention and animal drug supplies. Helping them to improve their businesses can be a challenge because conservative traditions in Pakistan bar many rural women from some economic circles. It’s hard to keep up with markets and technology when cultural restraints inhibit public involvement.

Fortunately, MEDA has experience in this. An earlier project facilitated go-betweens in the form of a culturally acceptable woman sales agent model — these are women who have more mobility and provide a vital link between the homebound women and the market. These agents help homebound women keep in touch with current market demands and thus fetch better prices for their products.

The Entrepreneurs project also adapted this intermediary feature in the dairy sector. In this case, a female village milk collector (FVMC), recruited from a less culturally-restrictive family, serves as the woman-to-woman contact to help women milk producers raise their incomes by linking them to improved market systems.

As the FVMC receives a commission from the buyer for collecting the milk, she has great incentive to get her suppliers to increase yields. Working with local partners, she also facilitates training to these women producers in basic animal husbandry, improved health and productivity. She also receives training in business skills and is linked to support services such as credit. Another level of intervention is to train certified female livestock extension workers (FLEWs) to provide extension services to dairy farmers. This is especially beneficial to a sector that is bound in tradition, with little current expertise in animal health. Nusrat Bibi is a good example. Last year she lost two animals to preventable ailments. One of her cows died from uterine prolapse (a disease during birth), and the calf of her buffalo expired due to severe diarrhea a few days after being born. Entrepreneurs’ basic livestock training introduced Nusrat to better management practices as well as the cause and prevention of common diseases. Now she knows all about the importance of regular veterinary check-ups.

The next time her buffalo gave birth, Nusrat was prepared. “This time my buffalo did not suffer from any disorder and the calf was quite healthy,” she says. Her buffalo now produces 12 liters of milk every day, of which she sells seven. This augments the family income by 8,400 rupees ($94) per month and enables Nusrat to afford a better education for her daughter.

Despite being the fifth largest milk-producing country in the world, Pakistan has one of the lowest rates of productivity per animal. Its dairy industry needs basic animal management, improved feeding and forage practices, better access to veterinary services and more efficient marketing systems that ensure increased milk prices for

A woman makes her daily milk delivery. Much milk spoils from lack of refrigeration, a problem that strategically located chilling units aim to remedy. A milk collector uses her test kit to gauge fat content and check for impurities.

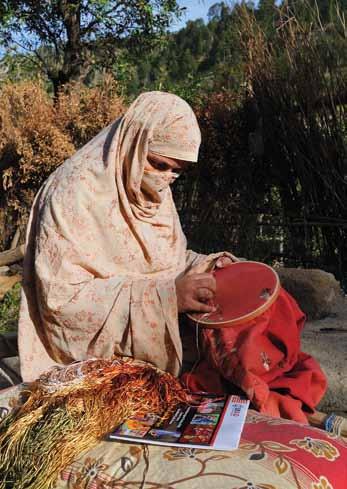

Embellished fabric — 26,000 clients

In Pakistan, the art of embellishing fabrics is as old as the country itself. But homebound artisans need help connecting with modern markets.

smallholder female dairy farmers. Small dairy farmers need collection points for chilled milk; some 20 percent of milk goes bad from lack of refrigeration. To this end, the project will install 80 milk chillers with 1,000-liter capacity through one of its local partners, at selected locations to bring the chain closer to major milk producing clusters and reduce spoilage.

Overall the project aims to triple the average cow’s production from an initial yield of half a liter per day. This is projected to increase incomes by at least 50 percent.

Part of MEDA’s longstanding strategy is to work with local partners who are well aware of the sector dynamics and are investing in the long-term development of dairying in Pakistan. In the dairy sector, one of its partners is Engro Foods, a leading milk processor in Pakistan. Through its various affiliates Engro contributes widely to the country’s betterment, such as by providing technical support to dairy farmers and their families. Working with the Entrepreneurs project Engro helped restore the productivity of 15,000 households through livestock feed, nutritional supplements, and inoculations against foot-and-mouth diseases. Engro continues to work with MEDA to increase milk yields and chilling capacity. In Pakistan, the art of embellishing fabrics is as old as the country itself. Wherever you go, you see shawls, shirts and cushions adorned with intricate embroidery and embellishment by women artisans who have lovingly preserved the historic indigenous craft. MEDA’s earlier project in Pakistan, Behind the Veil, demonstrated the economic value of connecting homebound women embroiderers with emerging new needs of urban markets. Since many women cannot travel themselves, the project equipped female sales agents who, unlike traditional middlemen, could conduct face-to-face

She tripled her earnings

Jamila and her husband, a day laborer, struggled to support their seven children on his small income. Despite having no education or experience in the formal labor market, Jamila wanted to help out by earning additional income. She did some embroidery and beadwork but had very few orders and earned only $7 a month.

“One day I was talking to a friend that I would like to find more work,” she says. “She told me about a training program that helped women like me earn a living.”

Jamila registered for the Entrepreneurs program on developing embroidery designs. It also trained her to represent other women to the purchasers of the embellished fabric, so that together they can offer bulk orders and receive a better price.

Today, Jamila manages a team of 65 women embellishers. She helps them obtain orders as well as collects and delivers finished products to the buyers. She now earns more than $20 a month, nearly triple what she earned before.

“I don’t have to think about what I will feed my children anymore,” says Jamila. “Instead, I can think about my children going to school and learning things I don’t know.” ◆

A class of homebound women learn to create new valueadded products and upgrade their business skills.

transactions with these homebound women and act as go-betweens to help the artisans update their designs for broader appeal, and serve as the key link to input suppliers and service providers.

Using that success as a model, the Entrepreneurs project is helping 26,000 embellishers across Pakistan strengthen their business capacity, participate more fully in the market and increase incomes by 50 percent by the end of the project in 2014. They learn to identify suitable products, access better markets and service providers, and create new value-added products. A valuable component is promoting products at exhibitions, trade fairs and e-commerce platforms. For example, a three-day sales exhibition in Lahore gave 300 female sales agents a chance to showcase the products of 6,000 flood-affected embellishers.

For Akhtar Begum, a 40-year-old widow with five children, becoming a sales agent opened a window that she could not open on her own.

“During the trainings we went on exposure visits and met with different retailers and wholesalers in the market in order to have a better understanding of market demands,” she says. “As a result, we can now differentiate between low quality and the best quality of inputs. Our products are more refined and market-oriented as we are acquainted with the color combination, proper stitch, design and tracing.”

A spin-off benefit is that Akhtar’s leadership skills blossomed, and she now works as a female sales agent and heads a group of 35 women in her community. “Em-

Bakht Bibi, 27, lives in a harsh, hilly region close to the Afghanistan border where she ekes out a living collecting and selling medicinal and aromatic plants. She and her four children yearn for a peaceful, secure life, but that is a lot to wish for in an area that has been wracked by conflict since 2009. To make things worse, flash floods in 2010 washed away her collection tools and the hillside plants on which she depended. She and other collectors were left helpless and without money to get back on their feet.

MEDA, through the Entrepreneurs project funded by USAID, implemented a post-flood recovery initiative that has grown into a long-term value chain project.

When she joined the project Bakht Bibi received a toolkit and training on better collection and processing procedures. She learned more about the species in the area and their market value. Now she is equipped to gather larger volumes of plants. “From the training I know how to keep the specimens clean and fresh, so I now get better prices than before,” she says.

Bakht Bibi and others like her have improved their business skills and formed lasting linkages with more reliable and lucrative markets. On average, they are earning more than three times what they earned before the conflict started. ◆

Pakistan’s mountains grow hundreds of species of valuable medicinal plants that are used to treat various ailments. Collectors are learning sustainable harvesting, drying and storage techniques.

A chance to start again

Akbar Ali had a small honey bee farm of 10 colonies and eight traditional hives to augment his income from a small sawmill. His life was turned upside-down by the devastating flood that left millions of Pakistanis homeless in 2010. It ravaged lush green fields, crops, orchards, forests and everything that came in its way including Akbar’s small house and bee farm.

“Although my ancestral profession is carpentry, beekeeping was my passion and I have been practicing it as a business for the last seven years,” he says. “Despite the tense conditions created by the militants in the past few years, I made handsome earnings from this business while gradually relinquishing my ancestral profession. In the last year or two the earnings from beekeeping were really heartening, but the 2010 floods washed it all away.

“We needed a solution to reinstate our destroyed business so that we could again provide for our families’ needs. The beekeepers, including my family, were helpless and didn’t know how and from where we could get food for our families. The support was a huge help as this enabled us to start our businesses again. Also, the boxes provided by USAID allow for harvesting of honey three to four times in a year resulting in more income. From our previous hives, we collected honey only once in a year. Honey is making money for us,” says Ali. ◆ bellishment has become a regular source of income for us,” she says.

Medicinal & aromatic plants — 21,000 clients

For generations, highland villagers in northern Pakistan have supplemented their farm income by collecting leaves, seeds and fruits of valuable medicinal and aromatic plants (MAP). The country’s mountains hold a treasure trove of 600 to 700 species used for pain relief, to reduce fever, or treat asthma. Others are simply spices like caraway or oilseeds like safflower.

These plants grow in challenging terrain where plungDespite being ing temperatures provide a small seasonal window for the fifth largest collection. The sector suffers from low quality, unsustainable and irregular harvesting milk-producing and extraction, and lack of modern techniques. Cultural country in the restrictions also limit mobility. But the trade is vigorous world, Pakistan and the potential for MAP as a fast-growing sector in has one of the Pakistan is very strong, says Slomback. An estimated 1.2 lowest rates to 1.5 million Pakistanis, mostly women, are involved of productivity in the collection of such plants. Over the life of the project Entrepreneurs aims per animal. to increase the incomes of

A changed life

21,000 MAP collectors by 50 percent. The project design includes When she and her husband separated two years training in sustainable collection, drying and storage techniques, as ago, Ameeran, 23, and her well as business basics son moved in with her fa- like marketing, costther. She didn’t want to be a ing/pricing and recordburden on him, but she had keeping. These skills no choice. are envisaged to help “I used to collect milk these MAP collectors and sell it seven days a improve their busiweek, working from three in nesses. the morning to sundown,” Even with several she recalls. hundred species, new Thanks to the training ones are still being and testing kit she received discovered by the from the Entrepreneurs Entrepreneurs projproject, Ameeran is now ect. Quercus fruit, for able to work on her own. example, was earlier

She collects milk from farm- seen as waste and not ers, checks its quality and even collected, yet it is composition using various famous worldwide as a tests required by commercial treatment for urinary marketers and delivers the tract infections and product to an Engro collec- diabetes. This and tion centre. other newly discovered She has managed to species are now being double her income and is collected and sold at proud to be economically in- good prices. dependent and a supporting hand to her father, rather Honey — than a drain. She also enjoys 5,000 clients working for other villagers’ betterment by giving them Beekeeping is a a better price for their milk. longstanding cottage

Another benefit is that she industry for tens of now works only two hours thousands of Pakistani prompted when the 2010 flood ravaged and washed a day, leaving more time for families. The bees are away 50,000 box hives, about half the industry’s capacother household tasks. important agricultural ity. Some 3,000 box hives were distributed to beekeep“This program has pollinators, and the ers along with bee colonies and beekeeping accessories, changed my life,” she says. ◆ honey they produce is through MEDA’s local partner, Hujra. sought after for One beneficiary was Muhammad Younas, 55, the household use. Despite father of seven children. He describes himself as “a the many producers, demand still outstrips supply. There beekeeper by birth” who joined his father in the family is plenty of room for expanding the quantity of hives and business when he was 10 years old. “My ancestors were increasing productivity. The Entrepreneurs project saw the pioneers of beekeeping in our village,” he says. “My strategic benefit in helping beekeepers grow beyond their father used to sell 80 to 100 kg of honey every year.” traditional mindsets and increase their knowledge of pro- The industry was already being disrupted by the rise duction inputs, markets, finance and technology. of militancy in 2009. “During the conflict most of the

The project set out to help 5,000 beekeepers (more bees either flew away or the colonies died due to heavy than half of them female) to increase their income by 50 shelling and explosions,” says Younas. “We hardly surpercent through training in hive management, disease vived it. Then came the floods that flushed away our prevention and better harvesting. remaining hopes. The assistance came at a crucial time; it

The Entrepreneurs Livelihoods Recovery Support was was a much-needed blessing.”◆

A vendor checks a supply of medicinal and aromatic plants, a vigorous and fast-growing sector in Pakistan’s markets.

A beekeeper tends to a traditional mud pot hive, which is built into the wall of her house. Bees from the nearby hills enter through a small outside hole. The large interior opening is used to monitor honey production and extract it when ready.

Net impact

Both users and sellers are big fans of MEDA’s mosquito net program

Hawa Bakari has become a MEDA convert — converted to the use of mosquito nets to protect her family from malaria, Africa’s greatest child-killer.

Hawa, 31, lives in a remote village of Karatu, Tanzania, where she supports her family by raising cattle.

She learned the hard way about the health benefits of an insecticide treated net that protects sleeping children from malaria-bearing mosquitoes.

When her first child was born, the attending nurse encouraged her to Hawa Bakari and child: “No more malaria.” purchase a net. But Hawa was not familiar with the culture of sleeping under nets. Even though many of her family members had contracted malaria in the past, she decided not spend the money on what she felt was a non-urgent expense. It was a costly decision. Her child was plagued with malaria as well as eye and skin infections brought by flies and other insects.

Hawa didn’t make that mistake with her second child. When she took the infant to Karatu Health Centre for a check-up, she was issued a voucher that she could redeem for a mosquito net. The voucher required only a small top-up fee of 500 Tanzanian shillings (equivalent to 32 cents U.S.), which she could afford. The top-up fee was important because it first of all signalled her commitment to actually use the net, plus it provided a financial incentive for retailers throughout the country to stock the nets.

“I bought a net for my baby and we have all been sleeping under it since then,” she says.

Hawa now has high praise for MEDA’s Hati Punguzo mosquito net voucher program. The net has protected them not only from malaria but also from other diseases carried by the insects that hover Abtwalib Dinya: “A way to give back.”

around her cattle. Her second child has yet to fall sick from these illnesses. Hawa puts her net to good use, even keeping her babies under it while she is doing house chores or tending to her cattle. “I see significant changes in my life,” she says. “No more malaria, and other sicknesses are reduced, too.” Hawa is now a firm advocate for the use of bednets. Abtwalib Dinya is one of the few retailers in the village of Goima in Tanzania. His tiny shop sells basic goods like sugar, butter, soap and teabags, but his favorite product is the mosquito nets he gets from Hati Punguzo. He has owned his shop for many years but only began selling bednets in 2007. He says his involvement with the bednet program has been extremely motivating for him because he can support his community and give back in a meaningful way.

Dinya appreciates new features of the program. Now he can text-message an order for more nets through the new electronic voucher system, and no longer has to travel 20 miles to restock his net supply. After ordering, the nets are delivered right to his doorstep. And the extra profit he earns from net sales has enabled him to stock his shop with other items that the villagers need.

His deepest appreciation, however, is for the way the program has curbed malaria. For personal, business and social reasons, Dinya hopes that the ownership and use of nets, especially among pregnant women and children, will go up. Since Hati Punguzo began, more than 30 million bednets have been distributed. Some 7,000 retailers throughout the country maintain a steady supply of nets for new customers or to replace worn nets. The program has saved an estimated 200,000 lives, mostly pregnant women and infants. ◆

Okra in an urban jungle

Garden project blooms in Haiti

More than two years after being hit by a devastating earthquake, Haitians still struggle to get back on their feet. A big issue remains the cost of food in the capital, Port-au-Prince, where households spend 51% of their income on food.

In the dense urban slum of Avenue Poupelard and Fort National, where houses perch haphazardly one atop another in a maze-like pattern up and down the hills, it’s hard to think of verdant growth. Nonetheless, MEDA, in partnership with Foundation for International Development Assistance (FIDA), is testing the feasibility of producing food and possibly some income on the many vacant spaces where houses used to stand.

Called Jadin Lavil (City Garden project), the venture trains would-be small scale farmers and gardeners to grow vegetables in every imaginable container, small plot and flat rooftop.

“In a country where post-harvest losses are huge and bad roads make it difficult to supply enough vegetables to the cities, growing them next door to the urban consumer makes sense,” says Ariane Ryan, project manager.

The project was launched in May, and swiss chard and okra have proven winning crops as they are easy to grow and bountiful.

“As the first participants are harvesting and adding much-needed nutrients to their diets, their neighbors are seeing the possibilities and asking if they, too, can turn their piece of urban jungle into vegetables,” says Ryan.

One successful practitioner is Bernadette Valomé, who was called back to the neighborhood of her youth to be by her mother’s side after the earthquake. In earlier days it was a pleasant area with a big open park and plenty of trees to sit under and enjoy the breeze. Now, 20 years later, the whole neighborhood is concrete, a hodgepodge of flat-roofed block houses on narrow alleyways. Most greenery has vanished.

Bernadette missed the gardens she gotten used to at her previous residence and sought to replicate them close to home. She saw an opportunity by connecting with Jadin Lavil. As a new gardener, she received training on plants, soils, pests and more. She accessed seeds and compost and learned to build up a plot, make seedlings and grow vegetables.

Ryan says that although Bernadette struggles to make ends meet, she has been able to help an ailing neighbor by making her soups and other meals using vegetables from her garden. “She now looks forward to leek season which, if successful, will help her save good money as she will no longer have to purchase the popular but expensive creole vegetable.” ◆

Steve Sugrim photo

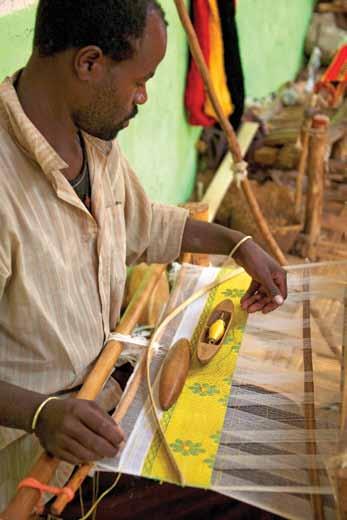

Weavers’ products take flight

Connecting rural artisans with higher-end markets is improving output and boosting income

In the hills of southern Ethiopia skilled weavers ply a trade handed down for generations. Hunched over looms in the open air, under trees or in makeshift buildings, they fashion bright fabrics to sell at roadside stalls or community markets. Now, thanks to MEDA, their output is finding new high-end customers.

The newest placement is on the uniforms of Ethiopian Airlines flight attendants.

How they got there is the latest chapter in the value chain story MEDA is writing among Ethiopia’s textile workers and farmers. The overall project aims to help 2,000 weavers (as well as 8,000 farmers) boost their income by improving output and connecting with higherend markets. The project goes by the name of EDGET, which stands for Ethiopians Driving Growth through Entrepreneurship and Trade.

Steve Sugrim photo

Designs collected from numerous rural locations were sent to the capital to be assembled into uniforms. What better way, the designer thought, to showcase Ethiopian fashion worldwide.

Gigi Fresenbet is a prominent Ethiopian de-

signer whom MEDA enlisted to help weavers update their production so it would appeal to higher-paying customers in shops in Addis Ababa, the capital. She spent time with lead weavers in two rural zones teaching quality control, design consistency, cost calculations and scheduling. The lead weavers then passed on the new expertise to others in their cluster groups.

One of the new orders Fresenbet arranged was for Ethiopian Airlines, which wanted a traditional teleb flower pattern for its uniforms. With the air carrier serving 69 international destinations, she saw an opportunity to showcase Ethiopian fashion worldwide.

She chose the group MEDA works with in the Chencha region because it is a center of traditional textiles and the weavers are highly skilled and showed promise in being able to quickly master the quality and consistency demanded by the airline. A group of 300 hopeful weavers showed up for the special training, and was soon

One of 65 weavers who made the final cut to produce designs for the airline.

winnowed down to 65. These weavers were already well experienced but needed to learn to create the new pattern, do it quickly, at a high quality level, and work to a deadline.

MEDA president Allan Sauder recently visited

The product the project and saw the airline order in production. of their looms “After seeing the beautiful green and gold pattern benow travels to ing worked on everywhere I was struck with the thought 69 international that soon all this fabric would be consolidated from these obscure locations, be destinations assembled into uniforms in Addis Ababa and then travel all over the world on jet airliners,” he says. “I wonder if the weavers could even imagine where and how their handiwork will travel the world.”

Sauder says he was highly encouraged by how the project has mobilized intermediaries to serve as a design and marketing link between the urban markets and the remote weavers. In the past, the intermediaries might have been likely to exploit the weavers, but “now they help to ensure quality and timeliness by wandering up and down mountains to visit weavers where they live and work.

“I really saw the tremendous benefit of the value chain approach MEDA is using. Everyone involved adds value to the process, and everyone shares in the profit.”◆

The heavens are telling

Was Mars ever hospitable to life? Roger Wiens wants to know.

When he was a boy, Roger Wiens and his brother Doug liked to play with model rockets in a vacant lot behind their home in Mountain Lake, Minn. Little did he know that someday he’d send a camera to Mars.

Wiens had a personal stake in NASA’s journey to Mars this summer. The Curiosity rover that was dramatically lowered onto the surface of the red planet carried an exploratory device created by Wiens and his team of planetary scientists at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. Called ChemCam, it contained a laser spectrometer and telescope device that can zap rocks, vaporize surface fragments and determine their chemical composition. When transmitted back to earth, the data can unlock the planet’s secrets and aid in the search for any trace of life on Mars.

In an article in the Christian Leader, the U.S. Mennonite Brethren magazine, Wiens reflects on the day in November 2011 when Curiosity began its journey aboard a 200-foot-tall Atlas V rocket. He and his wife, Gwen, watched from a small Florida bay four miles from the Cape Canaveral launch site.

“As the final second ticks off we see a flame appear under the vehicle as it lifts off the pad, gains speed and passes through a cloud and then arcs out over the ocean,” Wiens wrote. “Moments later the sound of the massive rocket engines reaches our ears. From our safe vantage point the huge rocket looks uncannily like the small models Doug and I launched as kids. But this one is carrying a one-ton, six-wheeled rover the size of a small SUV on its way to Mars. On the rover is our laser instrument called ChemCam.”

Years earlier Wiens had submitted a proposal for a novel device to analyze rocks and soils on the red planet without ever having to drive up or touch the samples. In 2004 he received word from NASA headquarters that the instrument had been selected for the next mission to Mars.

“The technique works by firing laser pulses at samples from up to 25 feet away and recording the flash of light from the impact spot,” he says. “The color of the light produced when a small amount of rock is vaporized tells us about the composition of the rock. The ChemCam instrument also takes high-resolution pictures of the samples it analyzes.” Wiens’s team delivered the unit to the rover in late 2010. Curiosity, by far the biggest vehicle ever sent to Mars, is only the fourth to operate on the red planet, says Wiens. He explains that the vehicle has a six-foot-long arm with a drill, brush and microscope. The arm can deliver samples to two inside instruments, one to determine the mineral structure of rocks, the other to investigate elements like carbon and nitrogen to look for organic materials, and to sniff for methane, a by-product of living organisms. A key goal of Curiosity is to determine Mars’ habitability. “Was it ever hospitable for life?” Wiens asks. “Once thought to be a dry and dead planet, we now know there were rivers, lakes and likely oceans on Mars in the past. Sedimentary rock layers are piled several miles high, indicating the major role that water played in the past, similar to on earth.” In his article Wiens muses as to whether Christians would be shocked if the rover found

Planetary scientist Roger Wiens pictured with a full-scale model of the rover Curiosity that landed on Mars with a laser instrument designed by him and his Los Alamos team.

evidence of past living organisms. He notes that C.S. Lewis, in an essay called “Religion and Rocketry,” raised the question of whether God could have created life on other worlds. Perhaps Christians should think more creatively about such matters, he says. “We need people like C.S. Lewis and scientists like Galileo, Newton, Kepler and others in our day, to think outside the box and to discover new things.” ◆

Why I am a planetary scientist

What caused me to go into the sciences? First of all, it was providential. But four ideas have kept me going in my career.

Seeing my job as my mission. I believe God places us where we are for a purpose. When I was younger I assumed that my career should involve doing something overtly Christian, such as working in missions or doing relief work in a third-world country. As a young adult I spent a lot of time in prayer over my future.

But the opportunities that I expected in those areas never materialized. Instead, a job working for NASA fell into my lap and then another NASA job, and so on. I believe God wants us to do well what he calls us to do, so I have pursued excellence in my vocation.

Recognition that “the heavens are telling the

glory of God.” This phrase is the beginning of Psalm 19, which goes on to say, “The skies proclaim the work of his hands. Day after day they pour forth speech; night after night they reveal knowledge… They use no words; no sound is heard from them. Yet their voice goes out into all the earth.” One thing that I remember from going to church as a child is the front covers of the weekly bulletins. There was an inspiring picture: a majestic mountain; a lush, green meadow in spring; a mountain stream reappearing from under the winter snow or, after the Apollo Moon missions, a view of planet Earth from the Moon. Most often a psalm about God’s majesty accompanied the images.

If images inspire us to consider God’s greatness, how much more should the details behind these images inspire us? And so these details, summarily considered science, are the voice in Psalm 19 telling us of the glory of God. Altogether, science tells us of the greatness of God. We would do well to listen more.

Understanding that “all truth is God’s truth.” Philippians 4:8 encourages us to think on “whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is admirable.” Science is a search for truth about God’s creation. I believe God commends us to satisfy our curiosity about his creation through the study of science. This stands in contrast to the view that we have to guard ourselves against heresies taught in the name of science. The real question in these situations is, “What is true?” Unfortunately, it seems that many believers are hesitant to really search out the truth in various areas of science. In my associations with scientists of all religious and “nonreligious” backgrounds, I find that most scientists are really searching for truth. Pursuing exploration as worship. No matter what motivation others have for doing science, we can do it to “Science tells us explore God’s creation, to understand more of his nature. This is exploration with a far greater purpose than simply of the greatness to satisfy our curiosities or to exploit new discoveries. Compared to a century or more ago, we now know of God. We that the universe is vastly larger than was ever conceived in previous times; the human genome is amazingly more would do well to intricate than might have been fathomed; far more species exist on earth than thought possible; and living listen more.” organisms inhabit more extreme places than we ever previously considered. Doesn’t that tell us something very exciting about the Creator? By bringing to light these amazing details we are pointing out the excellence of the One who brought about all of these things. That is worship. — Roger Wiens

Roger Wiens and his wife, Gwen, among the crowd gathered to watch the launch of Curiosity. The count-down clock is visible in the background.

Roger Wiens is a senior scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. His article is adapted with his permission from the Christian Leader, magazine of the U.S. Mennonite Brethren Church. Readers can follow the action at the Curiosity rover’s website: http://mars.jpl.nasa. gov/msl/ or at the ChemCam instrument website: http://msl‑chemcam. com/. His book on his space exploration adventures, Red Rover: Inside the Story of Robotic Space Exploration From Genesis to Curiosity, will be published in spring by Basic Books. You can also check out this You Tube video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=20nVBvf9KUo

Why I won’t hire people who use poor grammar

by Kyle Wiens

If you think an apostrophe was one of the 12 disciples of Jesus, you will never work for me. If you think a semicolon is a regular colon with an identity crisis, I will not hire you. If you scatter commas into a sentence with all the discrimination of a shotgun, you might make it to the foyer before we politely escort you from the building.

Some might call my approach to grammar extreme, but I prefer Lynne Truss’s more cuddly phraseology: I am a grammar “stickler.” And, like Truss — author of Eats, Shoots & Leaves — I have a “zero tolerance approach” to grammar mistakes that make people look stupid.

Now, Truss and I disagree on what it means to have “zero tolerance.” She thinks that people who mix up their itses “deserve to be struck by lightning, hacked up on the spot and buried in an unmarked grave,” while I just think they deserve to be passed over for a job — even if they are otherwise qualified for the position.

Everyone who applies for a position at either of my companies, iFixit or Dozuki, takes a mandatory grammar test. Extenuating circumstances aside (dyslexia, English language learners, etc.), if job hopefuls can’t distinguish between “to” and “too,” their applications go into the bin.

Of course, we write for a living. iFixit.com is the world’s largest online repair manual, and Dozuki helps companies write their own technical documentation, like paperless work instructions and step-by-step user manuals. So, it makes sense that we’ve made a preemptive strike against groan-worthy grammar errors.

But grammar is relevant for all companies. Yes, language is constantly changing, but that doesn’t make grammar unimportant. Good grammar is credibility, especially on the internet. In blog posts, on Facebook statuses, in e-mails, and on company websites, your words are all you have. They are a projection of you in your physical absence. And, for better or worse, people judge you if you can’t tell the difference between their, there, and they’re.

Good grammar makes good business sense — and not just when it comes to hiring writers. Writing isn’t in the official job description of most people in our office. Still, we give our grammar test to everybody, including our salespeople, our operations staff, and our programmers.

On the face of it, my zero tolerance approach to grammar errors might seem a little unfair. After all, grammar has nothing to do with job performance, or creativity, or intelligence, right?

Wrong. If it takes someone more than 20 years to notice how to properly use “it’s,” then that’s not a learning curve I’m comfortable with. So, even in this hyper-competitive market, I will pass on a great programmer who cannot write.

Grammar signifies more than just a person’s ability to remember high school English. I’ve found that people who make fewer mistakes on a grammar test also make fewer mistakes when they are doing something completely unrelated to writing — like stocking shelves or labeling parts.

In the same vein, programmers who pay attention to how they construct written language also tend to pay a "Good grammar lot more attention to how they code. You see, at its makes good core, code is prose. Great programmers are more than business sense" just code monkeys; accord ing to Stanford programming legend Donald Knuth they are “essayists who work with traditional aesthetic and literary forms.” The point: programming should be easily understood by real human beings — not just computers.

And just like good writing and good grammar, when it comes to programming, the devil’s in the details. In fact, when it comes to my whole business, details are everything.

I hire people who care about those details. Applicants who don’t think writing is important are likely to think lots of other (important) things also aren’t important. And I guarantee that even if other companies aren’t issuing grammar tests, they pay attention to sloppy mistakes on résumés. After all, sloppy is as sloppy does.

That’s why I grammar test people who walk in the door looking for a job. Grammar is my litmus test. All applicants say they’re detail-oriented; I just make my employees prove it. ◆

Kyle Wiens is CEO of iFixit, the largest online repair community, as well as founder of Dozuki, a software company dedicated to helping manu‑ facturers publish amazing documentation. His article is reprinted with permission from the Harvard Business Review.