45 minute read

Soul enterprise

It’s nice to be nice

The CEO of a huge U.S. corporation famously said, “I don’t have time to be nice.”

Don’t believe him. In today’s climate, he’d be a dinosaur.

While you’re at it, ignore the old line about “nice guys finish last.” It ain’t true. In fact, there’s a growing belief that being nice can actually give you a rung up on the ladder of success. That doesn’t mean you should fake nice, but you shouldn’t apologize for it, either.

Not all Christians are nice, but they are expected to be. The qualities society generally regards as “nice” are very close to what Christians aspire to as part of their faith.

One of the first things we learn in Sunday school is the Golden Rule (“Treat others the way you would want to be treated”). When we were kids we may have thought that made us wimps. Uh-uh. It can set you up for success — both as a Christian and as a worker.

Business language doesn’t usually mention “being nice.” It prefers to speak of “soft skills,” like customer service and relational savvy. An employee manual or job description might mention respect, sincerity, positive attitude, team player and so on. What it boils down to is “nice.”

Business functions best when it is characterized by the Golden Rule, says Kristin Tillquist in her book, Capitalizing on Kindness: Why 21st Century Professionals Need to Be Nice. “The business world is a place for the vibrantly, positively, dynamically nice,” she says, adding that if you mesh a caring attitude toward others with savvy competence you will be “an employee of choice.”

The same thing applies to the business itself. “Companies that make kindness part of their mission outperform those that don’t,” she maintains. Firms with plenty of “kindness capital” enjoy better productivity and less absenteeism. They also don’t get sued as often.

Noting that a main reason why people quit their jobs is because they feel unappreciated, Tillquist warns companies that “the best and brightest employees will not stay where they are not appreciated; they will seek out environments with flourishing kindness capital.”

She also warns against “kindness inhibitors” such as rude e-mail and cellphone behavior, brazen competitiveness and even bad table manners (clients and executive recruiters have been known to downgrade someone who is rude to waiters).

So don’t hesitate to practice the “niceness” of your Christian faith. You can’t really put it on your resume, but you can bet it will help you in the long run.

Excerpted from You’re Hired! Looking for work in all the right places, a career guide from MEDA. Available for free download at www.meda.org

A lousy day but thanks anyway

Ever wonder what God thinks if we only give thanks when things are going well?

Imagine this: A company ends the fiscal year with a great bottom line. The inclination is to thank God for a positive and profitable outcome to the year’s effort. Someone wonders — Last year was dismal. We lost money. Did we thank God then?

Sports fans can see a version of this played out in professional sports. Someone scores a touchdown and makes a religious gesture. We don’t usually see that happen when a quarterback is sacked or a runner is smeared after gaining a yard.

In his new book, Throwback: A BigLeague Catcher Tells How the Game Is Really Played, Jason Kendall (seemingly not a religious man) comments on this phenomenon: “A guy hits a single, claps his hands, and points to heaven? Getting hits is his job, that’s what he was supposed to do. Why doesn’t he do it when he strikes out? Wasn’t that part of God’s plan, too? You only thank Him when you get a hit? If God’s with you all the time, wasn’t He with you when you chased that slider in the dirt?”

Called to ... what?

What do the biblical writers say about “calling”? Was Moses called to herd sheep? Was Jesus called to make tables?

Not really, according to Will Messenger, executive editor at the Theology of Work Project.

It’s rare in the Bible for anyone to be called directly to a specifi c kind of work, he says in an interview in Christian History magazine. All believers are “called” to participate in God’s creative and redemptive work, but seldom to a particular “job offer.”

Exceptions include people like Noah, who was called to build an ark, and prophets like Samuel, Jeremiah and Amos. Bezalel and Oholiab were called by God to be chief craftsmen for the tabernacle (Ex. 31:1-6). Barnabas and Saul were called to be missionaries. But most people should not expect to get a call from a divine headhunter, Messenger says.

“At the very beginning of the Bible, God chose to involve human beings in the work of creation, production, and sustenance.... For most of us, calling means going about our so-called ordinary work, guided by Scripture and prayer rather than by dramatic pronouncements or events in our lives.”

Lacking a burning bush, how did people fi gure out God’s calling? “One way was through seeing what needed to be done to make the world like what God intends,” says Messenger. This often meant nothing more glorious than earning a living to support one’s family or neighbors. “People were also called to serve the good of the larger society, as when Jeremiah told the exiles in Babylon to ‘build houses and live in them; plant gardens and eat what they produce’.”

Are some jobs out of bounds? “The only jobs the Bible explicitly forbids,” he says, “are those incompatible with its values: for example, jobs requiring murder, adultery, stealing, false witness, greed (Ex. 20:13-17), usury (Lev. 25:26), damage to health (Matt. 10:8), or harm to the environment (Gen. 2:15).” Many parents ask their kids after school: “How was your day?”

What if kids asked parents the same question?

Children can learn a lot from hearing about your job. It can make you seem more human and accessible. It can show them that complex problems are solvable, says Cheryl Hotchkiss of World Vision Canada.

Here are fi ve things to share with your kids: • What you like about your work. This opens doors with kids, and might lift your own spirits. • How your job helps others. Who benefi ts? How would their lives be different if you weren’t there? • What you learned today. Did you pick up a new skill, or fi gure out how to make a grumpy colleague smile? • People you met. A new client or co-worker? Give your kids a window into a world they wouldn’t otherwise see.

• How your journey is unfold-

ing. Are you still learning? Do your children know what your dreams are? (News Canada)

Don’t leave your job at the offi ce

Overheard:

“Your job is a collection of activities that allow you to add value to the world.” — Todd Henry in Die Empty: Unleash Your Best Work Every Day

Money scrubber

Sending money across the pond used to be relatively simple. Not anymore. Rising corruption and terrorism have muddied the water for charitable organizations.

Sheri Brubacher was startled when an offi cial of Canada’s national police force suddenly showed up at MEDA’s offi ce in Waterloo, Ont., and asked to interview her and get a copy of her photo ID.

She of course complied, taking a break from her usual routine of sitting in front of a computer screen and processing global money transfers.

His visit was an ominous sign of the times in today’s world of global terrorism.

Brubacher does not come across as someone of interest to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. For the last 15 years she has worked as the foreign currency exchange and compliance offi cer for MEDA Trade, a for-profi t MEDA subsidiary that provides currency remittance services to international non-government organizations in Canada. By using bank and trading connections cultivated over many years, it can offer savings on money transfers as well as innovative ways to convert U.S. and Canadian funds into local currencies in more than 125 countries.

Last year Brubacher handled more than 2,000 transactions for 33 client agencies who needed funds converted to conventional currencies like euros, yen and British pounds, or “exotic” currencies like Kenyan shillings, Ethiopian birr and Nicaraguan cordobas. Clients ranged from Save the Children and Canadian Cooperative Association to Mennonite Central Committee and War Child Canada. Altogether the transactions exceeded a hundred million dollars.

For MEDA, the service provides two benefi ts. One, it helps clients (including MEDA affi liates) to maximize their funds to boost impact on the ground. Two, the modest spread MEDA Trade charges can end up producing revenue which gets recycled back into MEDA’s own programs.

MEDA Trade dates back to the early 1990s when Jerry Quigley set up a way to broker “debt swaps” for developing countries. By the time the global debt crisis abated, MEDA Trade was known for effi cient currency transactions and began offering a foreign exchange service. It could easily do so because it understood developing countries and had forged relationships with reliable New York

currency partners. Then came the rise of global terrorism, which dramatically altered the banking system and brought everything under intense scrutiny. In Canada, anyone transferring money on a regular basis soon gets to be on intimate terms with FINTRAC, a government watchdog that monitors international transactions to detect money laundering, fraud and the fi nancing of Sheri Brubacher with many currencies she has exchanged. terrorist activities. To operate in today’s climate means being subject to a whole new range of reporting and monitoring procedures. This new global reality has doubled Brubacher’s work load. She now spends a lot of time studying anti-corruption reports and keeping up with external audits and compliance issues. She has to patiently educate clients, some of whom are small charitable organizations that may bristle at what seems like unwarranted intrusion into their affairs, and help them get in the habit of providing appropriate fi les to federal monitors. For example, if more than $100,000 is being sent to an individual, confi rmation is required from the sending organization that the recipient is not a Politically Exposed Foreign Person (PEFP) such as a politician or senior civil servant. Even within MEDA, anyone who has check-signing authority has to be documented if they are a PEFP. If they are a PEFP, further due diligence is required.

Pushpins show some of the 125 countries where MEDA Trade has transacted foreign currency conversions.

“Some clients just shake their heads when I tell them what they have to provide,” says Brubacher, who admits to being frustrated on their behalf for all the effort that is needed to prove they are legitimate. “Everything we do is under a microscope, and we have to prove it over and over again.”

Some of Brubacher’s time

is spent “scrubbing.” That doesn’t mean “laundering” but rather being able to document for the authorities where money is coming from and where it is going. “Our whole database is checked daily against terrorist and sanction lists,” she says. “If we didn’t do this, our banks wouldn’t deal with us.”

In the financial world, MEDA Trade is known as a “money service business” (MSB) and as such gets a lot of scrutiny. “What’s being demanded of us is far more than in the past,” Brubacher says.

Some of the work is outsourced to companies that have come into being to perform these functions. Every day, all the information in MEDA Trade’s financial database gets compared to a series of suspect lists to see if anything matches. These lists can change overnight. “Recently we’ve started to get hits from Russia,” says Brubacher.

She is also duty-bound to report anything suspicious to the government and to the RCMP.

Why, one might wonder, would the feds care so much about a seemingly non-threatening agency like MEDA? As it turns out, charitable organizations are watched closely.

“Believe it or not, a lot of money laundering and fraud goes through charitable organizations,” says Brubacher. “They’ve been a hiding place for funds.” Some banks are so wary of this “suspect sector” that they’d prefer to avoid contact with MEDA Trade because it is owned by a charitable organization and deals with other charitable organizations.

All this means piles of extra work that Brubacher never had to do previously.

“It’s the cost of doing business,” she says.

MEDA Trade charges a small

spread for currency transactions, but much less than traditional transfer agents charge. With more than 2,000 transactions a year, worth a total of $104 million U.S., even a small spread adds up. Some years MEDA Trade manages to contribute a sizeable sum back to MEDA. For Brubacher, that is part of the win-win. “The client gets a good rate, and any profit we make goes back to serving the poor again,” she says.

She acknowledges that MEDA Trade isn’t the only way to move money. A client can simply use a bank and pay a bigger fee. There are also “foreign exchange boutiques” which do not have a mandate of serving the poor and also charge higher fees.

MEDA Trade can give Canadian agencies a better deal because it has access to the trading floors of several major banks while the agency might only have access to the local bank branch with its higher fees. Moreover, clustering several trades entitles MEDA Trade to a volume rate.

Another benefit is that working through MEDA Trade gives agencies a documented audit trail showing the exact rate of exchange at the time of the transaction and complete documentation from the banks.

Many banks, if asked to send to a remote place, will just send U.S. dollars — which likely means a

second fee when the U.S. funds are converted again. Also, each conversion necessitates additional accounting steps.

“When we send, say Kenya shillings, it simplifies bookkeeping for our clients,” says Brubacher. “It means more money ends up going to the beneficiaries rather than being spent on fees and additional accounting costs.”

Brubacher sees her work through the lens of MEDA’s mission to create business solutions to poverty. Beyond the tedium of reports and number crunching, she knows that even a routine wire transfer has a human face on the other end — a family getting access to good water, a sick child receiving treatment, a small farmer receiving technical aid. In each case she is helping other service agencies to amplify their work while also earning extra revenue for MEDA. ◆

Radical with a cause

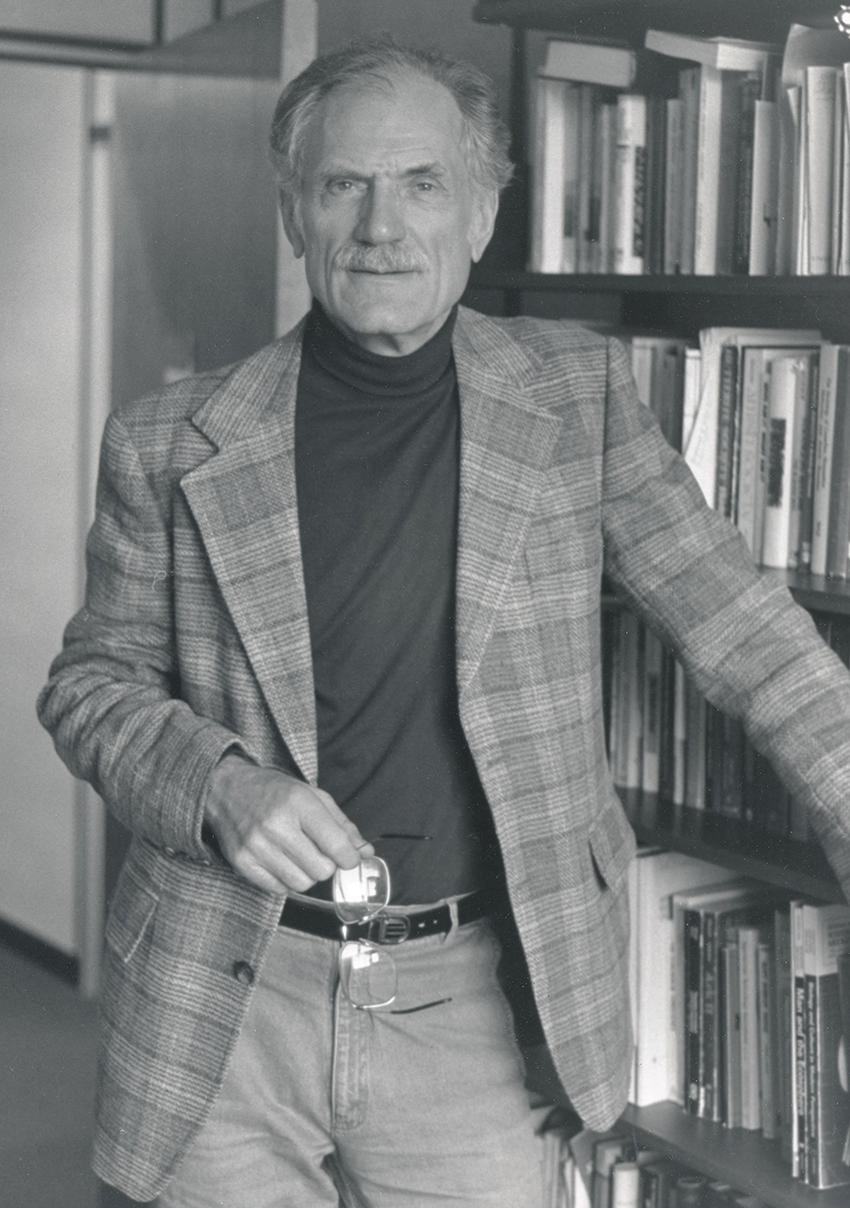

How a young college prof caught the business bug and ended up starting this magazine

Businesspeople in central Kansas took notice, 60 years ago, when a young scholar showed up and began asking pointed questions about faith and economics. What happened next would have an impact on Mennonite business for years to come, illustrating how clashing ideologies can be resolved productively. The account is based on Cal Redekop’s memoir-in-progress.

Cal Redekop arrived at Hesston College in the summer of 1954 for his first teaching position (social science). Full of idealism and energy, he challenged his students to think about traditional church positions on issues such as church authority, nonconformity, women’s roles — and especially wealth and materialism.

By the time he took a break for further studies, “1960s fever” was emerging on campuses across the country, and many students were protesting the “establishment.” Redekop felt the tension between market capitalism and Christian faith, and was particularly troubled that the individualism and self-interest he saw in capitalism didn’t mesh with Jesus’ teaching to “love thy neighbor.”

Freda Redekop, left, was the thoughtful presence who helped her husband (right) temper idealism with reality.

Excel Industries, then a producer of tractor cabs, embraced the young academic and urged him to put “skin in the game.”

“Armed with more sophisticated intellectual weapons, I returned to the campus with a freshly minted Ph.D from the University of Chicago in the fall of 1958,” Redekop recalls. “I expressed these convictions in my college and Sunday school classes. I semi-consciously reflected the increasing challenge to the status quo that was emerging in America.” Students ate it up but not everyone else in the surrounding Mennonite community was pleased. Hesston was seeing its own renaissance with the growth of local businesses, including a bank, auto dealership, turkey processing plant and lumberyard. Hesston Corporation was just beginning to make big waves. It was begun by an energetic Lyle Yost, who recruited a group of eager and dynamic young businessmen. It would become one of the largest agricultural equipment manufacturers in the U.S.

“Prosperity was in the air,” says Redekop, “and it was intoxicating.”

Rumors began to spread in the business community of a “young radical” at Hesston College who was questioning capitalism. When Redekop was invited by local Mennonite churches to lecture on “The Christian and Business,” he eagerly accepted, and proposed that Chris-

tians were called to a life of service, that material wealth was to be used for the benefit of others and that selfish accumulation of wealth was in-

compatible with the Christian life. He used the classic biblical text about a camel and the needle’s eye, and if that wasn’t enough, nailed down his argument with the story of the rich man who built bigger barns and thus lost his life.

“This bracing tonic immediately aroused lively discussions,” Redekop recalls.

Redekop’s critique created a stir among people like Lyle Yost, whose new company would become one of the largest agricultural manufacturers in the U.S.

One response was from Lyle

Yost, who found it all hard to swallow and promptly paid a visit to Hesston president Tilman Smith to complain. Yost, chair of the Hesston College board at the time, implored Smith to “constrain this radical who has no experience in the real world.”

Smith gamely held his ground. As long as Redekop maintained moral and intellectual integrity “I will stand by him,” he said, but still wasted no time calling the young professor into his office to suggest he cool his rhetoric.

Redekop was shaken. “I loved my teaching job at Hesston College,” he says. “I did not want to become alienated from it nor from the Hesston Mennonite Church, nor from the local businesspeople.”

He and his wife Freda talked it over. Perhaps he had been too radical and needed to more deeply consider other perspectives, Redekop mused. “How I could keep my growing convictions yet maintain a relationship with the community was not clear.”

Freda urged Cal to get involved in a business so he would have more credibility and could not so easily be brushed off as naive and inexperienced. He had already learned to take her counsel seriously. “Throughout our marriage Freda’s sage advice and support often helped me retain my idealism yet deal with reality,” he says. done for a young academic with graduate school debts and no savings.

Redekop conferred with his

friend Daniel Kauffman, business manager at Hesston College. Soon they had a plan, an entrepreneurial one, no less. They would buy an old house that had just come on the market, spruce it up and sell it for more. The two men and their wives took out a loan to buy the house and went to work.

“We had fun and fellowship cleaning, repairing and repainting the house,” Redekop recalls. “We sold the house for $6,000 within several months. Soon thereafter I walked

Redekop (front row, second from left) joined the Excel board and gained quick familiarity with the growing pains of a small company.

Accordingly, Redekop went to see John Reschly, who with Jonathan Mast had a young company (then called Hesston Industries) that made tractor cabs. He asked if he could become a “listener” in their company and learn how businesses run.

To his surprise Reschly welcomed him warmly. “I didn’t think an ‘academic’ person would be interested in our humble business,” he said.

But Redekop would have to “put some skin in the game.” Buy stock, in other words.

That would be easier said than into John Reschly’s office and plunked down Freda’s and my half of the profit, $1,000, for 100 shares.”

Reschly blinked. “To be honest,” he said, “I did not expect to see you come back.”

A lively learning curve awaited the new stockholder. The young company (later renamed Excel Industries) was an early leader in a rapidly expanding combine and tractor cabs market. It had all the typical growing pains of a small company. “Every day brought new crises,” Redekop recalls.

At the first meeting Redekop at-

tended he was appointed chair of the committee of five owners. “You are better at managing an ordered meeting,” they said.

His relationship with the new venture altered when Redekop was invited by D. Elton Trueblood to a new position at Earlham College, Richmond, Ind. But even at a distance he remained a board member for many years.

“I left part of my heart at Excel Industries, having tasted some of the excitement and challenges of starting something new,” he says. “My exposure to business had become extensive, and I became more and more interested by the concrete and challenging intersections of faith and business. I was beginning to like the stimulation and challenge of developing a business, and tackling the unpredictable.”

The company continued to flourish and instigated socially conscious employee and customer relations, including employee profit-sharing bonuses and 10% pre-tax profit contributions to the Mennonite Foundation. setting, and the programs did not survive Redekop’s later departure.

Teaching at Goshen College (1967 to 1976) gave Redekop a chance to further pursue these interests. In 1969 he was instrumental in creating Church Industry and Business Association (CIBA), an organization of Mennonites involved in a wide variety of businesses, from small service types to major supporting firms like Sauder Corporation, Shenandoah Equipment and Hesston Corporation. At the initial organizational meeting in Chicago, Redekop got his own dose of “young radicals.” Students from nearby Mennonite colleges were skeptical of this “capitulation to the establishment” and staged a protest. (Some later had a change of heart and became members.)

CIBA (later called Mennonite Industry and Business Associates) merged with the earlier Mennonite Economic Development Associates to form the present MEDA in 1981. The combined organization supported Redekop’s vision for a “business ethics journal” and invited him to become the first editor of The Marketplace, then subtitled “A Journal for Christian Business and Professional People.”

“My participation in these business-related activities opened up growing relationships with businesspeople, and I began to become less skeptical that business and the Anabaptist faith were totally incompatible,” he says. Still, he did not see business and Anabaptism as one cloth. The connection needed to be informed and led by robust Christian faith.

In time Redekop would write and publish widely on business ethics and faith ... and would become the founding editor of The Marketplace magazine.

He found he liked the stimulation and challenge of developing a business and tackling the unpredictable.

At Earlham (and later at Goshen College and Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminaries) Redekop continued to pioneer issues of business ethics such as an “Internship in Industry” program for theology students and other courses. Not everyone was warm to the idea of bringing the world of business into the seminary

Another related area

of work was the status of the environment. Redekop believes fervently that human “dominion” of the earth as mandated in the Bible has been tragically misunderstood. “The created world is indeed a most generous garden, to be lovingly nurtured and tended so it can be shared, not ravaged or exploited for personal gain,” he says.

This became an area for both business and scholarly attention. In 1976, while employed at Tabor College, Hillsboro, Kan., he launched a new company called Sunflower Energy Works Inc., which developed thermal solar collectors that would be widely used in central Kansas. When he moved to Waterloo, Ont., in 1979 to teach at Conrad Grebel College, he spearheaded a similar company there. After retiring from teaching he worked with the Environmental Task Force of the Mennonite Church and produced the book Creation and Environment: An Anabaptist Perspective on a Sustainable World (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000).

Few Mennonites have written more widely on business ethics and faith than Redekop. Throughout his academic career, alongside editing The Marketplace, he undertook numerous research projects relating to business. In the late 1980s he inter-

viewed more than a hundred Mennonite entrepreneurs across the United States and Canada, which led to the publication of Mennonite Entrepreneurs, published by Johns Hopkins

Is it good enough to act as ethically as possible within the system, or should Christians try to change the system?

University Press in 1995.

He and his son Benjamin then produced a book taking an in-depth look at 11 Mennonites and their businesses, published as Entrepreneurs in the Faith Community: Profiles of Mennonites in Business (Herald Press, 1996). He also continued to write articles in journals, magazines and books relating to Anabaptist principles in the economic arena.

In all these efforts one can

see the “young radical” of more than half a century ago wrestling with how to shine the light of Anabaptist faith into the economic arena. While early convictions that so inflamed some members of the business community have not dimmed, Redekop’s approach has softened and he has widened the conversation.

“One basic point of reference for me is simply the straightforward ethical teachings of Jesus regarding human compassion, economic behavior and amassing of wealth,” he says. “Though they seem overly simple, they are profound and express absolutes. Jesus’ parable about the rich farmer who hoarded his wealth and built bigger barns needs no exegesis as far as I am concerned. It’s clear as a bell. The man’s soul was lost because of his materialistic greed.”

What has not changed in 50 years is that wealth, for all its good uses and benefits, has a pernicious way of seducing and entrapping people in lifestyles that can be unwholesome, he insists.

“When people succeed, they assimilate the values and perspectives of the new status. Without the help of the ‘ethical community’ the drive for the lifestyles, security and power wealth brings will usually triumph.”

Wealth itself is not evil, depending on how it is gained and then shared with others, Redekop believes. “My involvement in the world of business has sensitized me to become more understanding of the problems humans face in the human (i.e. economic) production, distribution and consumption of goods and services, which are absolutely necessary for the survival of humanity.”

But, he adds, any economic system that does not limit human selfishness and environmental plunder is contrary to the Christian gospel.

“The fundamental issue, which has never been fully solved, remains: Is it good enough for Christians to act as ethically as they can within the economic system in which they operate, (even if it is based on a philosophy of self-interest) or should they also be involved in changing the system as much as they can? I believe Christians are called to the latter.”

Now retired in Harrisonburg, Va., (his wife Freda died three years ago) Redekop looks back on a rich career that took a decided turn when he and the Hesston business community confronted each other and took decisive actions to work together as fellow members of the Mennonite church.

“My activity in business has been a highly rewarding and important part of my life and it has expanded my horizons immeasurably,” Redekop says. “I have tasted the exhilaration of dreaming up a venture, making the jump and taking the risks and challenges, and the satisfaction of seeing it succeed.”

He looks back fondly on the late Lyle Yost, who challenged him early in his career and who also mellowed over the years. “We became good friends, and respected each other’s basic integrity and commitments,” says Redekop.

When carried out in the spirit of the New Testament, he observes, a clash between different orientations and perspectives can have life-changing positive consequences. ◆

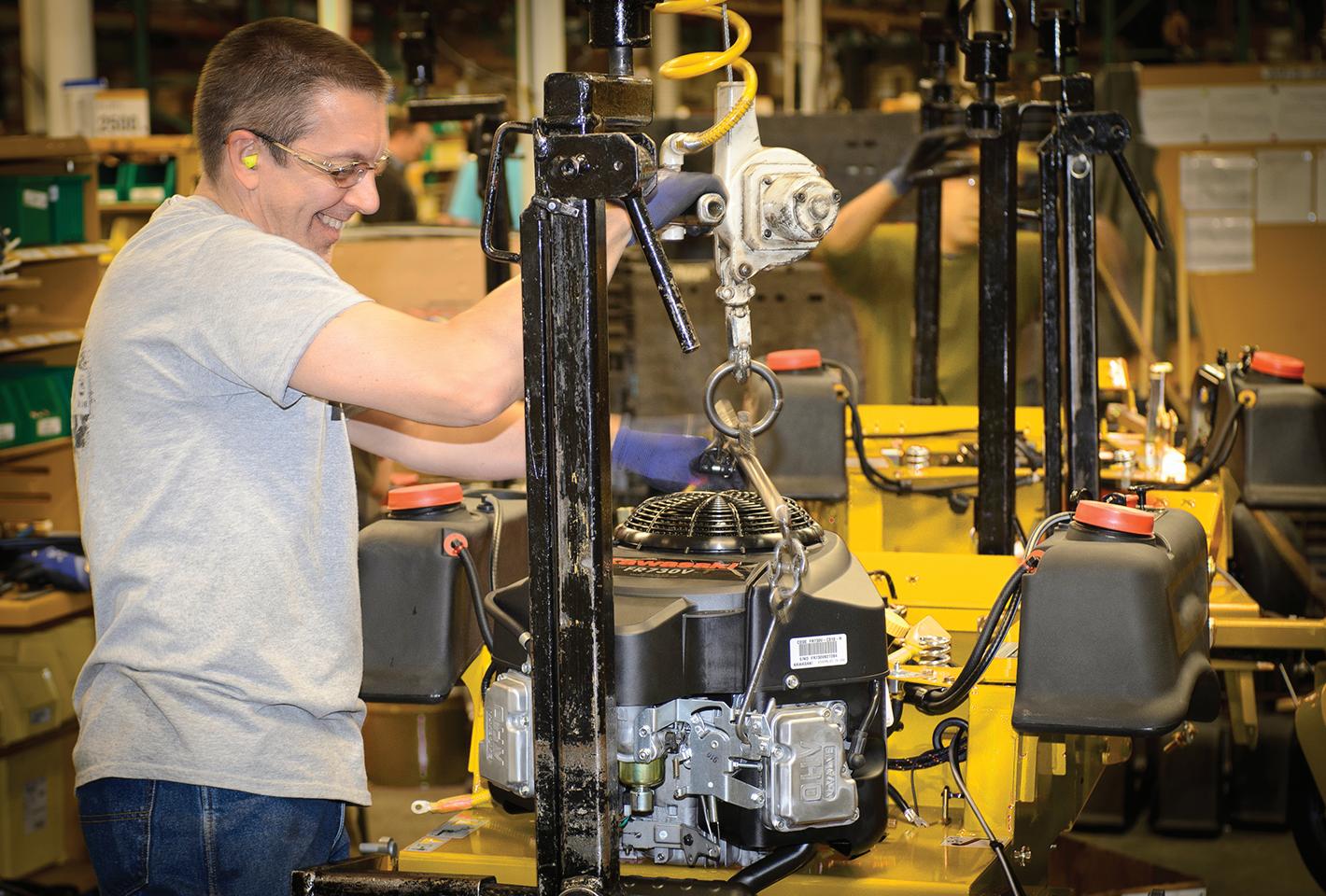

“I left part of my heart at Excel Industries,” says Redekop. The company, still based in Hesston, is a leading manufacturer of Hustler turf mowers.

Ukraine: Moving ahead despite uncertainty

The usual challenges of development pale next to the ravages of civil war

Running a development project can be grueling at the best of times. Civil war can make it nearly impossible, as MEDA found in Ukraine this year. While daily events in that region’s conflict alarmed readers across the globe, they nearly paralyzed those in the field.

The turmoil was sparked in spring when Russia annexed Crimea, traditionally held by Ukraine. This disrupted but did not erase the gains of MEDA’s Ukraine Horticultural Development Program (UHDP), whose first phase got 7,000 farmers working together to produce better crops and market them more profitably. A second phase (see sidebar), financed by the Canadian government, aims to strengthen small businesses (like processors and exporters) that support farmers.

Also affected was the progress of Agro Capital Management (ACM), a leasing company started by MEDA to equip small farmers with appropriate technology.

Fighting between Ukrainian troops and Russian rebels was concentrated in the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, and thus was not an immediate danger to MEDA staff located farther west. But some days staff in Crimea were told to stay home because of escalating hostilities.

Fear tactics still keep former staff on edge. In late summer armydressed personnel burst into a store in Melitopol and kidnapped several customers saying they were being recruited for the war. The detainees

were driven to a nearby forest and eventually released. A former MEDA staff member had been in the same store earlier in the day. The turmoil and uncertainty has complicated plans for the second phase of UHDP, says Nigel Motts, director of Private Sector Development – Agriculture. “We had hoped to be able to leverage our resources and experience from all the work we did in Crimea, to expand to other loca-

One achievement of UHDP was to get farmers — who after years of repression had developed a distrust of each other — to work together.

Russia’s retaliatory ban on imports may have a hidden benefit by strengthening markets for local farm commodities.

tions, but ground has been lost and we can’t count on continuing clients. Nonetheless we continue to operate.”

One upshot may end up helping clients of UHDP’s second phase. Russia’s retaliatory ban on agricultural imports (such as pork and horticulture products) from countries that

New leasing opportunities brought technology, such as simple greenhouses, within easy reach of farmers who could not previously afford it.

have imposed sanctions (Canada, the U.S., and the European Union) implies such commodities must now be sourced elsewhere. Ukraine remains Russia’s accessible, price-competitive source of supply for the horticul-

Phase Two gets $19 million

MEDA is partnering with Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada (DFATD) to extend and expand business development of horticulture markets in Southern Ukraine. This $30 million initiative is made possible through a $19 million DFATD contribution, announced by the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development. The remaining $11 million will come from various partners, private investors and MEDA itself.

Over the next seven years, the Ukraine Horticulture Business Development Project (UHBDP) will expand and extend the achievements of the UHDP, which MEDA operated from 2008 to 2013. The new phase will operate in the Southern Oblasts of Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Mykolayiv and Odessa and will seek to benefit 44,000 small and medium horticulture farmers and small enterprises. MEDA anticipates that small farmers assisted by UHBDP will have collectively expanded their horticulture sales to 50,000 metric tons valued at $40 million annually by the end of the project.

Ed Fast, Canada’s minister of international trade, said that despite the turmoil in Ukraine Canada continues to encourage sustainable efforts to create prosperity for Ukrainians. “Our efforts are focused on helping to create opportunities for small and medium-sized enterprises in key sectors such as agriculture, through improving business practices, increasing access to markets and financing, and creating jobs,” he said. ◆ ture products to be supported under UHDP’s next phase. Pragmatism may well allow such trade between Ukraine and Russia to continue, creating opportunities for UHDP’s farmers.

The impact of the conflict most directly hits ACM, which was recently sold to private investors connected with MEDA. With the seizure of Crimea, Ukrainian banks with whom ACM worked were shut down.

On the advice of MEDA’s security staff, key ACM personnel abandoned their homes in Crimea and moved their families and office to Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital. Financial operations have suffered as normal bank transactions have been severely curtailed. Loans cannot be enforced and courts cannot pursue action. Russian leaders have decreed that Crimean citizens (including ACM clients) do not have to repay Ukrainian debt. Enforcing Ukrainian property rights remains uncertain.

Nearly half of ACM’s portfolio was in Crimea, and that is in jeopardy. ACM is working with clients on repayment options for early repayment and offering discounts for paying out early. ◆

Dream on

Managers can be an employee’s most important developer

If you are a boss, is it your job to help employees fulfill their dreams?

Most employees want careers that are purposeful. How much should employers help make that happen?

“Nobody wants to find themselves in a dead-end job,” writes Bob Robinson, editor of The High Calling, a website on work and faith. “We want to be allowed to dream of better things.”

Robinson quotes Monique Valcour’s comments on the Harvard Business Review blog: “Job seekers from entry-level to executive are more concerned with opportunities for learning and development than any other aspect of a prospective job. The vast majority (some sources say as much as 90%) of learning and development takes place not in formal training programs, but rather on the job — through new challenges and developmental assignments, developmental feedback, conversations and mentoring. Thus, employees’ direct managers are often their most important developers.”

The burden, says Robinson, is on leaders to help people to fulfill their dreams. He sees it as an investment that eventually pays off. Like a venture capital investor who puts money into a start-up company, the initial financial outlay yields returns in the future. Likewise with employees — investing in them upfront enables them to flourish later.

“This takes effort to know who people are and what they dream to be,” he writes. “This requires a longterm vision of what will be needed for each person and for the institution to thrive, but it pays off in the end for both.”

Robinson points to Google’s well-publicized policy to allow its engineers to use a fifth of their work time on personal interests that have company relevance. This produces dual benefits. The engineers gain more satisfaction from their work and utilize their gifts to produce new technologies for Google. Gmail was one fruit of this policy.

For him, the issue has spiritual relevance. Christians who toil in a broken world can do their part to bend hard realities to something more in tune with a biblical vision — to work for righteousness in the

He quotes a founder of The Container Store: “If we take care of our people, our people will take care of our customers. And if our people take care of our customers, our customers will pretty much take care of everything else.”

This retailer, with some 70 stores nationwide, tests applicants to see how they are likely to perform. Once hired, the company devotes 50 times more hours per year than the standard in the retail sector to train and develop each employee. The company believes that most workers genuinely want to give their best effort and that their personhood has to be taken seriously in order to make that possible.

Hendricks says any strategy for adding to the bottom line has to ask how each individual in the company has been designed by God to add value. “As a leader, don’t assume people know how to answer that question. Most people have, at best, a very rudimentary understanding of their giftedness — the way God has designed them. The burden is on leaders to help people to dream about how their work matters and to discover their giftedness in order to fulfill those dreams.”

This includes positioning each person in a job that fits their skills, and then resourcing them with an environment that optimizes their capacity.

Hendricks also points to Hawaiian Falls, which operates five waterparks in Texas and employs mostly young people in their upper teens during its summer season. CEO Dave Busch says an important part of his mission in business is to build the lives of young employees, helping them develop maturity, a good work ethic and valuable experience. To

Can Christians in a broken world be helped to bend tough realities toward a biblical vision?

midst of evil and to show compassion to hurting people. The question then becomes, “How can employers provide that to their people so that when dreams are shattering, there remains hope for a better tomorrow?”

Robinson recently shared other writers’ stories of managers who help employees grow.

Taking care of your people

Investing in people actually is good for business, writes Bill Hendricks, president of The Giftedness Center which specializes in organizational effectiveness and individual career guidance.

this end he has full-time staff for employee development, professional coaches to provide leadership training, and chaplains at each park to attend to the personal and spiritual needs of both patrons and staff. He believes that if he cultivates the gifts of his staff, they will create an outstanding customer experience, which means more families coming through the turnstiles, and more often.

A boss who made space

Aspiring writer Billy Coffey took a job at a gas station so he could meet people and get story ideas. The gas station was full of stories “all wrapped up in the flesh and blood of the crowd of people who walked through those doors and handed me money every day. The rich and the poor, the saved and the cursed, the cheats, the ‘no-counts,’ the broken and the mended. I met them all. At some point, we all need to top off the tank in the family car. Gas is the great equalizer.”

One day Coffey’s boss caught him jotting ideas down in his notebook. He told him that from now on he could have an hour for lunch. “I’ll make sure you don’t get interrupted so you can do your scribbling,” he said. “The other eight hours you’re here, you’re paying attention. Right?”

For several years Coffey pumped gas and filled notebooks — “the greatest education I could have.”

He will always appreciate the boss who created space for his dreams.

“You would be amazed at the lengths people will go to in order to

How has each individ- ual in your company been designed by God to add value?

Dreams in cubicles

Parents like to encourage their children’s dreams and help them believe they can be anything they want to be. It’s harder to do the same for themselves, their coworkers and employees, writes Roxanne Stone, vice-president of publishing at Barna Group. Many working adults have seen too much of the daily grind and the politics surrounding their work.

When Stone described a new job to a friend she was startled to be asked about her greatest hopes and fears for the assignment.

“When was the last time you asked yourself what hopes and fears you have for the work you’re doing right now?” Stone asks. “If you are a supervisor, when was the last time you allowed your employees to infuse their dreams into the work they’re doing?”

Many people long for a dream job, but maybe that’s not the point. “Maybe the point is to bring our dreams to the job,” Stone says. “Dreams live in children. But perhaps, if we allowed them to, they could also live in our work cubicles.”

Stone likes to ask people, “What are your hopes and fears for a particular project you’re working on right now? What would it look like for you to ask your coworkers or employees that same question? How could their answers inform the project and/or the work each is personally doing on it?” ◆ help you reach your goals,” he says. “You will be more amazed at the tiny things you can do in order to help others reach theirs.”

Coffey has since written four novels. He makes sure his old boss gets a copy of every one.

The day his world crumbled

A caring boss put new life into Dan King’s dreams the day his child was diagnosed with diabetes.

“The idea of giving our toddler son two to three insulin shots and pricking his tiny fingers six to eight times every day to check his blood sugar levels was overwhelming,” King writes. “My wife was devastated. I had to be the rock. Diabetes felt like a death sentence to me, so I wasn’t sure how I could keep a positive outlook.”

In the midst of his hopelessness, the phone rang. It was his boss.

“Dan, take as much time as you need,” he said. “Don’t worry about your projects. You take whatever you need in order to get this settled.”

The boss had had a similar experience with his own son. “He understood exactly what we were going through,” says King. “He gave me every phone number I could possibly need for him and his wife, so that we could call them anytime we needed to. He was determined to make sure I knew they were there for us. That was the moment when the ground beneath me stopped feeling so shaky. That was the moment when I was able to look at the rubble all around me and know that I would be able to start rebuilding.”

That was 10 years ago. King not only was helped to get through a personal difficulty, he also learned that people are more important than projects. “My projects could be resumed whenever I was ready to come back,” he says. “Until then, they were on hold.” ◆

In good hands

It was their business, their ministry, their legacy. It wasn’t something to pass on to just anybody.

It’s a dilemma faced by many who start a business they love. They pour their lives into it, then one day have to make difficult decisions about succession.

If family members are waiting to take over, the choices may be easier. But what if the next generation feels called in a different direction?

That’s the prospect faced by Levi and Lillis Troyer when the time came to find new owners of a retirement community campus that had been at the core of their lives for decades.

The story of Walnut Hills

Retirement Community stretches back to the legendary Emanuel Mullet (Lillis Troyer’s father) and the many Ohio businesses he created.

Mullet was a consummate entrepreneur with a brain for business and a heart for helping people. He got into senior housing when a motel came up for sale and Mullet wanted to convert it into a nursing

Lillis and Levi Troyer at their home overlooking The Meadows, an independent living community at Walnut Hills. (Photo by Doyle Yoder Photography)

home. “He had the feeling that we ought to help elderly people,” says Levi, who at the time was just about to marry Lillis. “He asked us if we would be interested in joining him. I had a little inheritance money, and Emanuel matched that. We went to the bank for the balance.”

“When we opened in 1961, we did a little bit of everything,” says Lillis. “We were really young. People used to come in and ask Levi for the manager.” She laughs. “He was the administrator and managing partner.”

They started Shady Lawn Nursing Home with 39 beds. “We worked our tails off, worked all the shifts,” says Levi.

Within six months it was filled. They added 11 beds and built a new dining room. Later they added another 50 beds.

They bravely navigated the learning curves, like regulations and inspectors. “We had to grow into that,” says Lillis.

In the meantime, a passion for senior care took root.

One day they visited the Walnut Creek area of Ohio and were smitten by its beauty. They promptly bought a 64-acre farm, on which the retirement community now sits, and sold Shady Lawn.

Walnut Hills Retirement Community started in 1971, first with 50 beds, then a hundred. One day as Levi and Lillis walked through the facility it struck them that a lot of elderly people there were still active and didn’t require much care.

“They were misplaced in a nursing home,” says Levi. “Assisted living was new then. So we decided to build a retirement home that would

require less money and less care. We’ve been growing ever since.”

One of his enduring memories is the trust people placed in Walnut Hills, and how energizing that was.

“When we saw how the people accepted us and trusted us and put their confidence in us, that was huge for us. People were looking for a place they could trust, and we were able to go the extra mile and do things that other places weren’t doing.”

Theirs was one of a few

privately-owned retirement communities in Ohio. Most were non-profit and church-related. Walnut Hills was often confused with a non-profit because of its forthright Christian principles.

Walnut Hills, with 250 residents, is located on a picturesque 110-acre hillside campus. When it came into being the area hadn’t yet become a tourist mecca, says David Miller, who managed the facility for 28 years. But that was about to change. “People liked the area; it was an appealing place, a nice place to live. Some people came back regularly to visit and ended up deciding to retire here. Most of the independent living people are from 30-60 miles out. It has become well-known as a scenic, safe place.”

Walnut Hills Retirement Community photo

When they reached their

Walnut Hills was

much more than a business “People were looking for a place they could trust, and we were able to go the extra mile and do things that other for the Troyers places weren’t doing,” says Levi Troyer.

“It was our baby, our ministry,” says Levi.

In nearly three decades of working with them, David Miller saw that conviction lived out. “It’s been more ministry than business, even though we were successful, business-wise,” he says.

“I have always felt that it’s a Christian businessperson’s responsibility to create an environment that is fulfilling and meaningful to people,” says Levi. “One dimension of that is a participative style of leadership. I don’t think people will give you their best unless they feel they’re an integral part of the team.” He learned that from father-inlaw Emanuel Mullet. “He gave me a lot of space.” Levi gives much credit to his employees, more than half of whom have Amish or Mennonite background. Their work ethic and values were an employer’s dream. “Our absentee rate was one percent,” says Miller. “People show up. They’re dependable. They have compassion.” That can work both ways. Miller remembers an employee who was diagnosed with cancer and soon faced a $100,000 medical bill for a stem cell transplant that wasn’t covered. “The Troyers said to pick it up,” he says. “That person is in remission, employed and healthy. It was money well spent. We missed it then, but don’t miss it now.” In another case, an employee had passed bad checks and was facing jail. Levi went to bat for her. He wrote to the judge: “We need this person and we’ll look after her and make sure it won’t happen again.” That was more than 30 years ago. “That person never wrote another bad check,” says Levi. “And worked for us for a very long time.” mid-60s the Troyers began wondering what was next for their family and for the institution. They knew “doing succession right” was not a matter of magic. “As the old saying goes,” says Levi, “an important measure of success is how you pass it on.” By now Walnut Hills had become a substantial capital intensive enterprise with a significant investment in infrastructure and a considerable operating budget. Over the years the Troyers had left their money in it so they could continue to develop the campus with low debt. Their other business interests in the hospitality industry (such as Der Dutchman restaurants) had done very well. They began to study succession. They called in family business consultants to help. First they looked at what was right for the family. One son had worked in the business for some time and there was hope others would also get involved. After some processing it became clear that family succession was not the way to go. “At Christmas banquets I would tell staff they could rest assured that this place was never going to pass into strange hands; it was going to stay in the family,” says Levi. He laughs. “And I was dead sure that was going to happen. We wanted to pass on the goodwill and friendships

to the next generation, and we naively thought that’s what they wanted, too. But we discovered that’s not where the family was at.”

The next step was to look for an appropriate business model that would preserve their core values even without family involvement. They brought in consultants to get a bead on the future of long-term care.

“They told us a lot of things we didn’t want to hear,” says Levi.

The business model for the next generation was likely going to be different than what had worked so well thus far. Baby Boomers were coming along with new demands for different kinds of specialized programs and more private rooms, all of which would require substantial capital.

“So we started thinking about selling,” says Levi.

One option was to sell to another private institution and give up control. This might have brought top dollar, but what if the buyer just stripped it down and completely changed the culture they had worked so hard to build.

“Meeting with three different conglomerates didn’t help our unease,” says David, their son who was deeply involved in the whole process.

“We always walked out of there just about feeling sick,” says Levi. “While there would have been more money there were never any good answers about how they would operate, or who would operate it, or whether they would just re-sell it. They never had any good answers for long-term operation.”

Another model was to work within the long-term relationship they already had with Greencroft Communities of Goshen, Ind., and reorganize as a not-for-profit. They were pleased when Greencroft

Family succession had been their hope, but that wasn’t to be.

showed interest. At that point Greencroft had five facilities in northern Indiana, with 900 employees and 1,700 clients. While the money would be less than if they sold to a conglomerate, Walnut Hills would be able to continue its program, expand its values, and be a community churchrelated non-profit organization.

“It seemed like the timing was right for them, and for our family,” says Lillis.

This is the option they finally chose. Greencroft did not buy it outright but contributed its expertise and financial muscle to form a new Ohio not-for-profit corporation, which has a long-term affiliation with them for management expertise and support. Observers say the Troyers left a sizable amount on the table to make sure the institution can grow and thrive, and thus perpetuate what was important to them.

In the final analysis, even the big city lawyers who handled the transaction were impressed by how the various parties worked together. Said one, “What a picnic to put things together for you people because you have the same goals and want to be fair to each other.”

Walnut Hills has now been under Greencroft’s operation for six years. David Miller remained as president for the first two years of the transition. He is now a charitable services representative for Mennonite Foundation/ Everence Financial in Kidron, Ohio.

“The transition worked very well,” he says, noting that Walnut Hills recently began work on a $3.5 million, 17,000-square-foot rehabilitation center with 20 private rooms.

Greencroft CEO Mark King agrees. “We’re pleased with how it’s Doyle Yoder Photography

Last year the Troyers donated a pavilion (background) to the Walnut Hills campus. From left, David Miller, longtime former manager; resident Paul Ankrim, primary mower and park caretaker; and Levi Troyer.

working out,” he says. King gives much credit to the Troyers’ philanthropic spirit, since they not only discounted the price significantly but also contributed back to the new organization as their commitment to its strength and survivability. Levi and Lillis Troyer live adjacent to the campus and remain active in advising on big picture campus enhancements. They have no regrets about the route they finally chose. They know their legacy is in good hands. ◆