22 minute read

Soul enterprise

Meltdown malaise

You’ve wondered about that colleague or employee who is stressed out by the economic crisis. Maybe you see erratic behavior, or detect signs of depression. How do you “walk alongside” without offending, or even making things worse?

Understandably, workplace stress is rising as people worry about their mortgage, pension or job security. More employees are seeking help for mental strain. Calls to employee assistance programs have jumped 10 percent in recent months.

In New York, business chaplains have been busier than ever counseling dazed employees. Churches are offering courses on coping with stress in uncertain times, and are stepping up personal counseling and job coaching.

Some warning signs: changes in work, eating and drinking habits; despondency, withdrawal and irritability; declining performance on the job.

How do you respond without being intrusive or creating a liability problem?

Experts say showing that you care is already an important step. Asking “How are you coping?” is more invitational than “I think you have a problem.” Don’t try to be the expert. Be ready to suggest the use of a company EAP or other professional.

Employers can run the risk of liability. If you are the boss, writes Elizabeth Bernstein in the Wall Street Journal, “you should offer only work-related help. Hand out the number to your employee-assistance program. Try to lighten someone’s workload. Encourage the person to take a vacation. Offer additional time off without pay.”

A recent survey found that only 13 percent of senior executives are keenly aware of the impact of mental health on their organizations.

Too smart to listen?

Jesus talked about people who “hardly hear with their ears” (Matt. 13:13).

Turns out that could apply at work.

We’re told that most people hear only half of what’s being said to them, and really listen to only half of that. Which means we grasp only a quarter of what is being said. So in a 20-minute meeting with a boss or employee, the average person hears 10 minutes, and registers only five.

Why is that? Researchers say it’s because our brains function four or five times faster than people talk, so our minds wander to fill the gap. Seems we’re a bit too smart to be good listeners.

We may be missing some good feedback. But if we’re not listening, we may never know.

How to solve the problem?

One way is simply to begin a meeting by jotting down “5 to 1” on a piece of paper to remind you that your brain needs to slow down and be a good listener.

Another way is to take notes of the meeting as a form of mental discipline.

Finally, commit yourself to asking at least five questions during the discussion. That forces your brain to pay attention. (Ragan Report)

“We may have many different jobs or labors (like raising a family, becoming engaged in politics, or playing in a band), but we must somehow find a way to express the creativity and calling of our soul or we will be the worst of failures.” — Patrick McCormick in U.S. Catholic

“The next generation workforce wants to do more than just make a paycheck. They want to do good in the world, as well.” — Marc Benioff, CEO, Salesforce.com

Jesus as entrepreneur

Jesus was a carpenter, but what did that mean in biblical times? Ed Silvoso thinks we underestimate the extent of Jesus’s primary trade. In his book Anointed for Business, Silvoso says Jesus would have been taught his trade in his early teens, so by the time of his baptism he would have been working at his profession for many years. “He was not a mere apprentice but a well-established artisan,” Silvoso writes. “I suspect that many of his neighbors ate at tables made by Jesus and secured their homes with doors built in his shop. Their houses could have had beams cut and fit by the Savior. Even some of their oxen may have worn Jesus-made yokes.”

He probably ran his shop at a profit, Silvoso says. “His daily business routine likely included the calculation of the cost of goods and labor, the interplay between supply and demand, the establishment of competitive pricing, the measurement of potential return on his investment, the estimation of maintenance costs and the replacement of equipment. Even though it may be unusual, even uncomfortable, for us to picture Jesus working to make a living, this is precisely what he did for most of his adult life.”

Think you’ve got a useless job?

“By the time I graduated from college I had held all kinds of menial jobs: bus boy, janitor, gardener, irrigation-pipe mover, window washer. I don’t recall enjoying any of them, but I learned how to keep at a job and not cut corners, even when nobody is watching. I learned that working hard at a job is actually easier than loafing at it.

“Some parents question the value of low-skill jobs, such as flipping burgers at McDonald’s. I believe the key lessons of hard work can be learned very well at such places. True, a job selling hamburgers won’t make a splash on your resume. It will, though, teach you how to show up on time, behave responsibly, do your duty without shirking and get along with your coworkers. With those lessons learned, you’ll do all right in the working world.” — Tim Stafford in Never Mind the Joneses: Building Core Christian Values in a Way That Fits Your Family

Climbing the ladder

Want to be a CEO someday? You may be able to boost your chances with some foreign experience, according to a new study. More than a third of Canadian corporate leaders have worked globally, such as in Britain, Europe, Mexico and other Latin American countries. This is up from 25 percent two decades ago. For CEOs in the financial sector the figure is almost double. “Research suggests that the ability of a CEO to operate at a global level is greatly enhanced by having prior global experience,” says a co-author of the University of Western Ontario study. (Globe & Mail)

Overheard:

“Anybody can observe the Sabbath, but making it holy surely takes the rest of the week.” — Alice Walker

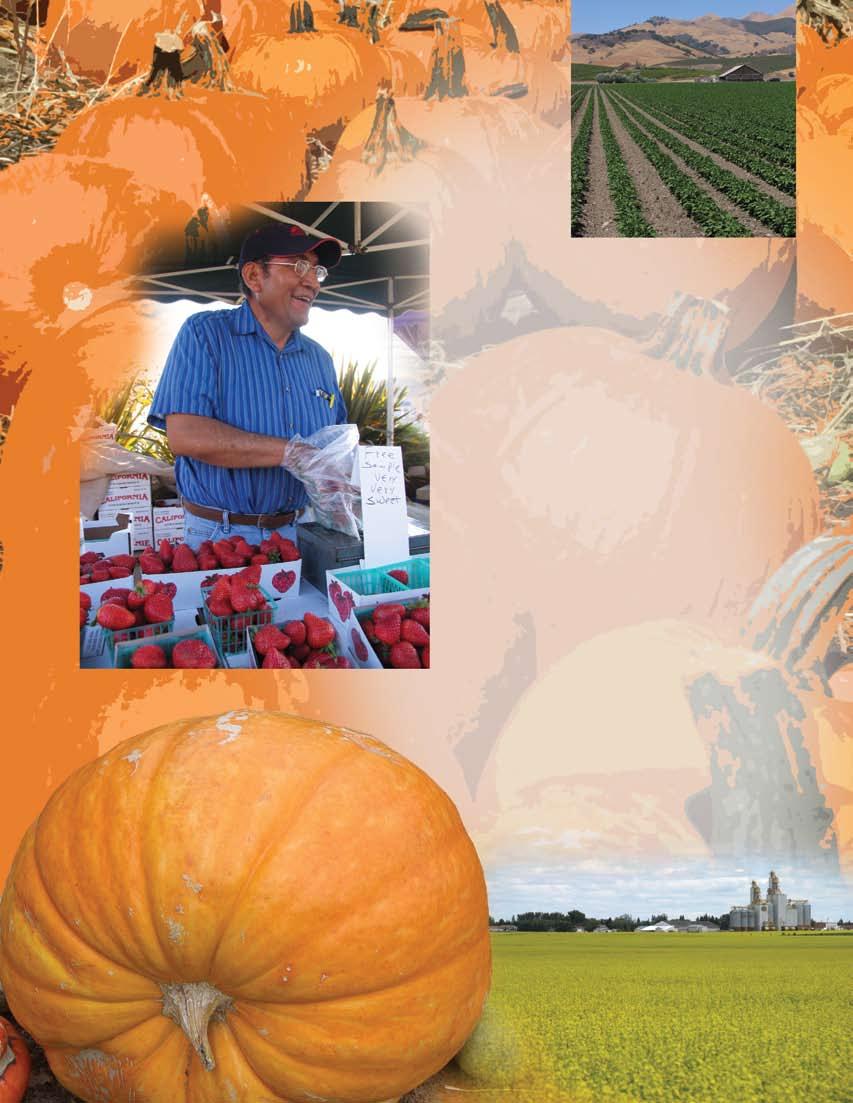

New project in ancestral Mennonite region banks heavily on “lead farmer” model

by Wally Kroeker

Elionora Seitvelieva thrusts a bag of tomatoes into our hands as we leave her backyard greenhouse in the village of Belogorsk.

“Here, take these,” she says in Ukrainian. “They are the best-tasting tomatoes in Crimea.”

We happily accept them for a later treat, as we are already snacked-out. We have been served refreshments at every stop: fresh strawberries and pears at one; honeysoaked nuts and medicinal herb tea at another. Elionora has just served us olives, dainties and tiny cups of stiff black coffee.

Later, the tomatoes live up to her boast, succulent and full of flavor.

We have seen tomatoes everywhere — climbing up along greenhouse trellises, piled high on roadside stands, served as the main ingredient of salad. Tomato juice is a national favorite, much more popular than apple or orange.

Allan Sauder, MEDA’s president, Kim Pityn, vice-president of international operations, and I are here to observe MEDA’s new Ukraine project in progress. For me it is a fresh experience. I’ve visited many projects over the years, but never at this early stage. It will be a chance to accompany local staff and observe how they gather data and fine-tune their approach.

People like Elionora and her husband Ibragim are not MEDA “clients” but rather models of what we hope our clients will become.

Helping smallholder farmers is nothing new for

MEDA, but this venture has some different dimensions. For one thing, it aims to help farmers who occupy land that was collectivized after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Back then, thousands of Mennonite farmers were driven off their land in the sweep of communism and fled empty-handed to Canada. For many Canadian Mennonites, the Crimea and other parts of present-day Ukraine hold a mythological grip as the Eden-like land where forbears transformed the barren steppes into thriving farms. My own mother was born only a few hours’ drive from where Elionora and Ibragim’s greenhouse now stands.

In recent years Mennonites have come in droves to trace their roots. Many have joined humanitarian efforts to assist impoverished Ukrainians. That altruistic impulse has not gone unnoticed by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), which sees it as a commendable act of reconciliation. CIDA is contributing the bulk of a $10 million project to help 5,000 farmers improve production and marketing of table grapes, potatoes, tomatoes, cucumbers and medicinal herbs.

The project is one of MEDA’s biggest so far. It will work in two oblasts (large regional jurisdictions) — Crimea and Zaporizhzhia, both regions once farmed by Mennonites.

On our visit, we see considerable administrative progress. An office has been set up in an industrial area of Melitopol. Another is being established in Simferopol. A strong staff is emerging. Field project manager is “We can grow Steve Wright, an American who lives in Ukraine, has a Ukrainian wife and speaks the crops that language. His development experience includes project can’t be grown management work in Tajikistan. elsewhere.” Another local hire is Oleg Osaulyuk, a veteran agricultural specialist who has long experience with agricultural supply firms and the United Nations Development Program. He holds a master of science degree in horticulture, with a major in economics, and has completed PhD work at the University of Bonn, specializing in the adaptation of western management to Ukrainian agriculture. An important early step in any new project is to build relationships with other agencies already on the ground. Accordingly, we visit the local office of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and sign an agree-

ment to share information and collaborate. We arrange to visit a UNDP cooperative project promoting the picking, drying, packaging and marketing of medicinal herbs.

Along the way we pick up the director and an agronomist from the Association of Farmers and Land Owners of Crimea, our implementing partners and in whose headquarters we will locate our Simferopol regional office. They came into being in 1991, shortly after the break-up of the Soviet Union, and remain the only source of extension services to farmers in the area. They represent 400 farmers, ranging from tiny to large. Director Mykola Havrylyuk thinks there is potential for 10 times that number.

Members of the cooperative gather wild fruit

and leaves from the countryside and bring them in to be dried under the sun or in a home-made kiln. The floor of the open-air compound is spread with bright patches of rose hip berries, wild apples, pears and the leaves and husks of walnut trees, which will be blended and packaged as tea or other formulations. We are given samples of their commercial tonic which promises to cleanse bodily toxins. But we are less interested in pharmaceutical claims than in the economic vigor of their enterprise, which we want our clients to emulate.

We visit a wholesale market in the town of

Sadovoe. It operates seven days a week as an outlet for farmers who hawk their wares out of the trunks of their cars — cabbages, peppers, tomatoes, cucumbers and apples. Most of them have 10 to 12-acre farms. There are more than a thousand small farmers in the region, many with greenhouses. We’re told the community has 600 acres of “kitchen gardens,” and a hundred acres under plastic.

It’s the only market of its kind, and buyers come from all over Ukraine and as far as Moscow. But customers who want to buy in quantity are disappointed. The small growers do not have the capacity to build large shipments. When the crop is ready, it can’t wait.

That can work against them. “When the frost came we had to harvest all of our cabbage right away,” recalls one grower. “The price fell.”

Now they have the same worry about tomatoes.

The problem is storage. A temperature-controlled facility would allow them to assemble shipments to meet large orders, and relieve the urgency of selling from the field. They’ve sketched out the costs, but Steve Wright, who has experience in such things, thinks they have vastly underestimated the size they need.

MEDA staff enjoy hospitality at the home of Elionora and Ibragim Seitvelieva (standing). From left, Steve Wright, field project manager; Kim Pityn, vice-president of international operations; and Allan Sauder, MEDA president. At right is Anna Shlyakhova, who represents a wholesale market in Sadovoe. Wild rose hip berries dry in the sun, on their way to becoming medicinal tea.

We visit farmer Marlen Sary-Belyal who

grows tomatoes and lettuce year-round. His plastic shrouded greenhouse is 50 metres by 10 by three metres high. While a commercial greenhouse that size can cost $10,000, he built his own for $2,000 but has to replace the plastic annually. He can recover that cost in one good year.

Like most small farmers here, Sary-Belyal has no access to credit. He managed to finance his greenhouse by scrounging and borrowing from family members, hardly a sustainable long-term strategy.

“The next stage in this village is obvious,” says Oleg Osaulyuk. “They need storage to market jointly rather than marketing separately and competing in price.”

Nikolay Choropita, an official with a large

private company in the village of Roschino, shows us big

grape fields irrigated with water from the Dnieper River. He is vice-president of a farmers association that helps its members with crop advice and equipment. Some of their growers’ problems are typical of what MEDA will encounter.

“We can grow crops that can’t be grown elsewhere — grapes, peaches, early apples, early and late potatoes,” he says. “The climate here is very advantageous for early varieties.”

That works well for the local market, which includes tourist resorts along the Black Sea. But he would like to boost production capacity for the lucrative European market. One obstacle is getting up to European standards for appearance and packaging.

He says they need several large central facilities to store, package and perhaps process crops, adding that Ukraine is seen as a second-class producer and is sometimes taken advantage of by large foreign companies. We ask why outsiders are not investing in Crimea’s infrastructure. That leads to a lament we hear over and over again.

“There are contractors in Europe who have asked about setting up a storage facility,” he says. “But owning land is hard here.”

A thorn in everyone’s side is a government moratorium on the sale of agricultural land. Investors are reluctant to risk any land-based initiative if they can’t get clear title.

The moratorium is due to expire, but with the political scene in flux, many expect lawmakers to take the easy way out and simply renew the moratorium while they deal with issues they find more pressing.

Instability aside, some producers are doing well on a small scale. Choropita takes us to a quarter-acre vineyard that has just been harvested. By his estimate, a vineyard like this requires an investment of $10,000-$15,000 per hectare (2.47 acres), so the woman who owns it would have invested around $2,000. In this, her third year of operation, her revenue was $5,000.

“Our goal is to get our clients up to her level,” says Wright. “She has gone as far as she can go, and now needs marketing and storage help.”

She has more undeveloped land available. “We will learn what to do next to get her family to do more with their undeveloped land.”

Back at the MEDA office in Melitopol we meet

with local credit union representatives. The president tells us the four financial institutions in the area have a combined total of 20,000 members, small by North American standards. Eighty percent of their portfolio is agricultural. She confirms the vigor of the greenhouse sector and its growing needs and demands. With a higher volume of savings, they could issue more loans, she says.

Other agricultural experts note the lack of affordable credit for small farmers. “If you buy a tractor here you have to pay 26% interest or more,” one tells us.

We get back on the road and drive north to the city of Molochansk in the Zaporizhzhia region. This is the

One community has more than a hundred acres under homemade plastic greenhouses.

Tomato grower Ibragim Seitvelieva is a likely candidate to serve as a “lead farmer” in MEDA’s project.

heart of the old Mennonite area. In pre-Soviet times Molochansk was known as Halbstadt, then the administrative center for the Mennonites. We are here to acquaint new MEDA staff with the region’s historic Mennonite roots. Accompanying us is Doris Wong from CIDA’s office in Kiev. She asked to join our tour to better understand the Mennonite history of the region.

Our visit includes a trip to the historic estate of Johann Cornies, the legendary “Johnny Appleseed” of the Mennonite colonies whose many innovations helped fashion the Mennonites’ vaunted agricultural prowess a century earlier.

We also visit the Mennonite Centre, located in a

historic Mennonite girls’ school which has been refurbished by Mennonites from Canada and which operates humanitarian outreach programs in the area.

A local farmer, Sergei Kondyrevych, has agreed to meet us and explain the current farm scene. He and his family grow wheat, sunflowers and watermelon. One of his chief constraints is lack of water in an area with annual rainfall of 17 inches. Good water can be found at a depth of 25 metres, but getting access is a problem. Drilling a well for irrigation would cost $5,000, but the bigger issue — common in Ukraine — is a permit. In one of those puzzling realities of Ukrainian life, it costs $20,000 to obtain permission to drill. Few can afford it.

Since this was a region once famous for agricultural bounty, we wonder what had changed. Is there less rainfall now than a century ago? Has the climate changed due to global warming? Could moisture conservation measures, like minimum till, be encouraged?

We also wonder about the project’s appeal to North American Mennonites who have roots in Ukraine. Would some of them want to invest in their ancestral homeland?

We also visit with Mikhail Soroka, who runs a Molochansk nursery that produces certified grape seedlings and garlic seed for sale to Russia. He is fortunate to have access to an artesian well for irrigation.

“The climate here is ideal,” he says. “Our crops ripen faster than in other areas.”

On our way back

we review all we have seen and heard and discuss how MEDA staff will refine their approach. Clearly, a recurring issue is refrigerated storage so produce doesn’t have to be sold the minute it is harvested. Addressing that need will open the doors to creative new marketing strategies. Another central issue is farm credit, with which MEDA has plenty of experience. The project will bank heavily on a “lead farmer” strategy that MEDA has used in Africa and Asia. It selects model farmers, gives them additional training and resources, and lets them serve as community mentors to help others on their way up. Some farmers we met have already agreed to serve in this role.

It is generally felt that small farmers here, who are as independent and resistant to outside advice as farmers everywhere, are not likely to change their behavior through technical assistance alone.

“People in villages aren’t good at sharing,” one specialist told us. “They like to keep their secrets to themselves.” Moreover, another advisor says, many rural people still hold to “old-type Soviet thinking.” Working together on their problems doesn’t come easily. “Many still expect the state to look after them,” he adds. The lead farmer model is expected to help as small producers see the success of the lead farmers and think, “I can do that.” We are reminded that the successful farmers we have met are not the target of this project. “We will target people who we want to get there,” says Kim Pityn. “Our goal is to bring 5,000 clients to that level.” All in good time. Stay tuned. ◆

“Our crops ripen faster than in other areas,” says Mikhail Soroka, who runs a Molochansk nursery that produces grape seedlings and garlic seed.

A grower hawks tomatoes at the wholesale market in Sadovoe, a community with 600 acres of “kitchen gardens.”

Table graces

by Gerry Derksen

Blessed are You, Lord, our God, Creator of the Universe, who brings forth bread from the ground.

Blessed are you... for earthworms toiling through hard clodded dirt for all things dying that feed the earth, for rich dark soil soon giving birth.

Blessed are you... for cycles and seasons in unending stream, for sunshine and rain turning world green for ozone protection beyond sun screen.

Blessed are you... for plants yielding seed and fruit trees with fruit, for potatoes, tomatoes, sending down root, for canola and barley pushing green shoot.

Blessed are you... for chicken and cow, for salmon and snail for lobster and crab, pheasant and quail for creation’s shed blood nourishing all.

Blessed are you... for gardeners and farmers, ranchers and breeders for shovels and pitchforks, tractors and seeders for satisfied labour and sabbath’s good rest.

Blessed are you... for butchers and bakers and cabbage roll makers for drivers and packers and sorters and stackers for checkers still cheerful at end of long days.

Blessed are you... for fridges and freezers, ovens and toasters, for mixers and blenders and electric can openers, for microwave ovens we can’t do without.

Blessed are you... for tastebuds and flavours and festive mood, for cooks and chefs and artists of food, for all things tasty, yummy and good.

Blessed are you... for love and for laughter circling the table for cross-cultural friendships erasing Babel, for eating that binds us one to another.

Blessed are you... your presence at table in bread and in wine, you graciously calling all people to dine, ‘till grand kingdom banquet in fullness of time. AMEN.

Gerry Derksen is part of the pastoral team at River East Mennonite Brethren Church, Winnipeg.

Business in his bones

It’s hard to draw lines when you live above the store, says new CMU prof

by John Longhurst

Lots of people can say they grew up in a business family. But Craig Martin grew up in a family business — quite literally.

Martin, who directs the new Business and Organizational Administration program at Canadian Mennonite University (CMU) in Winnipeg, spent the first 10 years of his life living above his family’s hardware store in Picton, Ont.

“It was hard to draw a line between the family and the business,” says Martin, 42, of living in the combined business and residence. “The two were pretty synonymous.”

From an early age Martin worked in the store after school and on weekends, stocking shelves, sweeping floors and helping customers. At age eight he was assembling bikes. As for pay, “it was called room and board,” he says.

After his parents sold the store in 1976, he worked summers at his grandfather’s dairy farm. “Farming was also a big part of my life growing up,” he says, noting that two uncles were also dairy farmers. “I really enjoyed time spent working at the farms.”

Both experiences ingrained in him an interest in business and agriculture, and a healthy respect for small business owners and farmers.

“I learned the importance of a strong work ethic from my parents and relatives,” he says. “I also learned about the importance of thrift, about the need to handle money carefully, and how to treat employees.”

When the time came to settle on a career, Martin merged his two interests by studying agricultural economics and business at Ontario’s University of Guelph; his Ph.D. dissertation is an economic analysis of the demand for dairy products in Canada.

Although he will be teaching all areas of business at CMU, the growing and selling of food remains a special interest. “With all the competition at the local, national and international levels, you have to not only be a good farmer, but also be good in business to be successful,” he says.

Also of interest to Martin is the issue of food aid. “We need to send food to hungry people around the world,” he says. “But we have to do it in a way that is not destructive to farmers in poor countries.”

For Martin, the best way to help hungry people is by buying food locally or regionally. At the same time, he acknowledges this can be a sensitive issue for some North American farmers who also have come to depend on their governments buying surplus crops for foreign aid shipments.

“While we want to support farmers at home, we need to be careful that food aid programs aren’t more about providing support for domestic agriculture than truly helping needy people,” he says. Of the new business program at CMU, Martin says that he wants to see students graduate with “good, strong technical skills that are equal to any business school,” along with “strong ethics and a keen social awareness based on Christian beliefs and values.” At the same time, he says the program will be a good starting point for students who want to work in the non-profit sector.

“The same principles that govern businesses apply to non-profit groups,” he says. “Non-profit groups measure outcomes differently than businesses, but both have to use sound business and organizational practices to ensure they are meeting their goals — whether that’s making products or serving needy people.”

Martin is especially grateful that MEDA’s Winnipeg chapter has signed an agreement with CMU to support the new program through things such as internships, mentoring and collaborating with the university on business-related forums and events.

“I look forward to working with MEDA members to help students become successful in their careers in business, or the non-profit sector,” he says. “MEDA’s involvement is important to the success of the program.” ◆

Craig Martin

John Longhurst is director of communications & marketing at Canadian Mennonite University.