4 minute read

Caving Phil Hendy

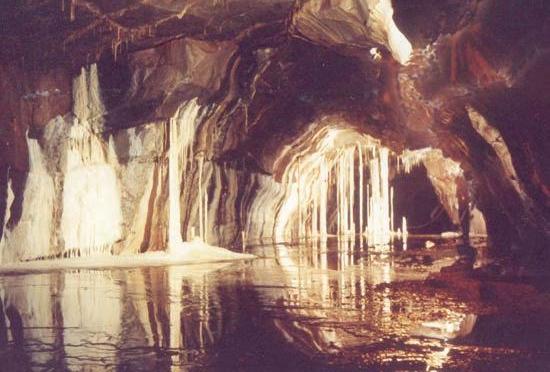

Snowflakes and lily pads – some cave formations

With PHILIP HENDY

ONE of the most uplifting aspects of caving is the chance to view and admire a beautiful chamber or grotto, adorned with all manner of calcite formations. In its purest form, calcite is simply refined limestone or calcium carbonate. Water, made slightly acidic by atmospheric carbon dioxide or from decomposing vegetable matter, seeps down through the rock and dissolves small amounts

of it.

When this water drips into a cave, it can evaporate, leaving a tiny deposit of pure white calcite. If there are minerals in the rock, traces of these can be carried down as well, staining the formation red, yellow, pink or black depending on which mineral is present.

Like snowflakes, no two formations are exactly the same. Stalactites grow down from the roof; they are usually thin and pointed, but can form long hollow straws. Stalagmites are broader and stumpier, as the calcite-rich water splashes and spreads out as it hits the floor.

Sometimes, however, they grow tall and relatively narrow, like candles. Given time, stalactites and stalagmites may join, to form a column.

Water running along a sloping crack in the cave roof can allow the formation of a long translucent curtain. Changes in the rate of flow or route taken over time can lead to banding of different colours or hues. On sloping surfaces, a film of calcite will build up, and small ridges or dams can build up.

The pools which they retain are called gours and they can be very large – the Fonts in Gough’s Cave are a good example. If the water trickles down sufficiently slowly, crystals will form in the pool, and if there is no draught, they can grow on the surface of the water.

This is known as cave ice. If the crystals growing up meet this ice, the calcite on the surface may grow thicker, and a formation known as a lily pad occurs.

A steady drip from a great height into the pool may cause another type of formation, the cave pearl. Small crystals or pieces of grit in the water are kept moving; calcite accumulates, and the movement smooths and rounds them. They may grow as large as a blackbird’s egg, or even larger.

Some of the strangest formations are helictites. They can grow on any cave surface, even on other formations, and are thin strands of calcite, which defy gravity and twist and turn in all directions. Their growth was at one time thought to be determined by draughts, but it is more likely that erratic crystal growth is responsible.

A common question is “How quickly do stalactites grow?” The answer being “it depends.” A ball-park figure is 0.13mm per year, but this can rise to 3mm per year in the best conditions. Generally, we think of a centimetre growth in 1000 years.

We have all seen the formations which can grow under concrete bridges and these can form at a much higher rate. Some tape, placed in Shatter Cave to protect formations, has become completely cemented to its supports in less than 20 years.

In South Wales, The Columns in Ogof Ffynnon Ddu are more than two metres tall, but are probably less than a hundred years old. They lie below a disused limekiln, where the calcite is easily dissolved, and then redeposited in a large section of cave passage.

It is known that stalactites have growth spurts and rest phases, depending on climatic conditions. By cutting though a stalagmite, and then examining the growth rings (a bit like dating trees) an estimate could be made of its age, but this is destructive.

Today, a small core is drilled from the formation, and the ratio of uranium to thorium is calculated. Uranium decays at a known rate into thorium, so the more of this element there is, the older the formation. Knowing the age of a stalagmite can also help us determine the age of the cave.

Calcite is not the only substance of beauty and interest to cavers. Surprisingly, mud can also intrigue us. This material is washed into caves by streams, or may be the insoluble remains of rock and minerals. Like rock, it can be deposited in discrete layers, which again can help in dating the cave’s development.

If left to dry for long enough, it cracks and resembles crazy paving. A rare phenomenon occurs when small stones are left on the surface of the mud. Dripping water landing on these pebbles will slowly erode the surrounding mud, leaving the stone sitting on the top of a thin mud column. Even the rock itself can be transformed into strange shapes.

Water and abrasive grit can work it into all kinds of strange smooth forms, while small streams flowing over a slope can wear the rock into a series of grooves, like a miniature river system. These rills are collectively known as rillenkarren; they are known on the surface as well.

Any caver taking their time to explore a cave and keeping a good lookout, is bound to see at least some of these features in any cave, even the most popular. They add intrigue and interest to the trip for anyone keen to make the most of their time underground.

Gours in Little Neath River Cave Columns in Ogof Fynnon Ddu