11 minute read

Thermal recycling - part of the solution not part of the problem

August - september 2021 Part of the solution not part of the problem

Thermal recycling is reliable, makes environmental sense and has no technical alternative, says Infrastructure Publisher Mike Bishara

Advertisement

Whatever name you choose -- waste to energy programmes have an image problem they do not deserve.

New Zealand has imported the simplistic “one size fits all” solution to landfill solution from the EU as a convenient and politically palatable solution.

But even the European Commission’s most staunch supporters defiantly incorporate an acceptable face of incineration in their circular economies, which are far more advanced than New Zealand.

One such facility built by Danish Engineering firm Ramboll quickly became a landmark and tourist attraction in the centre of Copenhagen.

It has a ski slope on its roof, hiking trails, the world’s highest artificial climbing wall and a mountain bike trail.

The waste incineration plant was completed in 2017 and has an annual capacity of 400,000 tonnes.

And it was to Ramboll that Cambridge designer Neil Laurenson turned to plan a waste to energy conversion plant in Huntly.

His $650 million plan 'Kaitiaki', would process items that could not be recycled, reused, composted or repaired and would work within what Laurenson described as "the circular economy" of waste.

It called for a sea change in the way New Zealanders dealt with rubbish. Laurenson planned to have barcode scanners in every New Zealand home to help consumers identify which items were recyclable and which were not.

The country's rail network and truck network would be utilised to transport waste to the new plant.

The size of the factory would be dictated by how integrated this circular economy became. The more robust it was, the smaller the plant.

As well as turning waste to fuel, there would be a tyre pyrolysis plant to convert old tyres to fuel and a recy-

cling centre.

His idea initially won the backing of Waikato's economic development agency Te Waka and there were plans to promote a joint feasibility study with government and regional business.

Then the doomsayers moved in. New Zealand Product Stewardship Council's Dr Trisia Farrelly called it "a false solution" to New Zealand's waste problem. "All you end up doing as they do in Scandinavia is 'feed the beast'. The thing could only keep going as long as you feed it waste, so it perpetuates waste." "What we need to be doing is investing as much funding as we possibly can into prevention. Transporting the waste to a single site in the North Island would also generate huge carbon miles,” she says.

“Many public discussions ignore the fact that there will never be a perfect circular economy linked to a utopia of zero waste and infinite recycling without needing any energy or decontamination,“ says Christophe Cord’homme at French equipment manufacturer CNIM.

“There will always be the need to have waste to energy as a safe final sink for polluted waste that can no longer be recycled. Whoever denies this probably also believes in the myth of perpetual motion.”

Attempts by Infrastructure News to find out the current state of play with Laurenson’s plans have drawn zero response.

EU thinking, upon which New Zealand relies, is coming under increasing pressure. Its conventional wisdom holds that if waste incineration can no longer be funded, countries will have to find other ways of processing waste.

In theory, the EU believes this will lead to even more recycling, even more waste prevention and to new and improved methods of disposing of any remaining residual waste.

“The objections against which we have to defend ourselves are all too often irrational,” says Ella Stengler, Managing Director of the Confederation of European Waste-to-Energy Plants.

Stengler is critical of the fact that incineration has not been included in the EU’s Green Deal taxonomy, which lists the technologies that are considered to be sustainable and which should therefore receive funding.

New Zealand looks to be on a path to follow the EU with a persistent conviction that incineration causes lock-in effects and hinders both material recycling and waste prevention.

“In practice the regulation [will] create a disastrous lock-in effect as far as landfills are concerned, especially in countries that have not yet developed a waste incineration infrastructure.”

This is a view shared by Cord’homme. “On the one hand, how does the EU intend to reduce landfill to less than 10 percent if at the same time it makes it more difficult to finance waste-to-energy plants?” he asks.

“Wherever waste to energy is used, not only does the use of landfill decline, but more material recycling is carried out at the same time,” says Stengler.

“That’s logical. Incineration requires a well-developed, reliable collection system up front. Where such a system exists, it’s also easier to separate individual fractions and recycle them materially.”

Thermal recycling would be a way of achieving more waste separation, and thus automatically more material recycling too, through the upstream collection systems.

And that may be the rub for New Zealand. A 2019 Berl report says the Zealand waste sector is dominated by two large companies, Waste Management and EnviroNZ.

These two companies control the majority of New Zealand’s waste either through direct contracts with private customers, or through waste service contracts with energy authorities.

Any future large-scale Waste to Energy facility will need to work with these companies to source the waste volumes required, says the report.

They are unlikely to support a move to Waste to Energy given the investments they have made or will be making in new or expanded landfills, the report says.

From a technical point of view, energy recovery of residual waste is already at a very high level and advanced thermal treatment technologies will probably not lead to either lower emissions or a better energy yield says Johnny Stuen, Production Director at the Agency for Waste Management in Oslo.

“I don’t think we’ll see much change here in the next 20 to 30 years.” With even better filters and with carbon capture systems, he says, the emissions balance could be improved even further, but basically there is only room for small optimisation steps.

“If material recycling is not possible and we don’t have clean mono streams, mixed material, incineration is the best solution,” says Stuen.

It looks set to be a long haul, whatever the direc-

tion is taken. In Antwerp for example, despite all the waste prevention and recycling efforts, the volume of household waste that cannot be recycled remains constant, at around 183,500 tonnes per year.

The old plant has reached its limit. A new building ready in six years will not only facilitate state-of-theart technology, but will also drive the expansion of the district heating network and thus contribute to achieving the climate targets.

The new plant will even be prepared for developments that are currently still far from market maturity, such as carbon capture technology.

Still, technical facts alone will not create acceptance no matter how impressive they may be – and nor will mere figures, says Kristel Moulaert Managing Director of the intermunicipal waste management organisation ISVAG, formed by the Belgian municipalities of Antwerp, Mortsel, Boom, Puurs, Niel and Hemiksem,

Moulaert is currently making sure all the arrangements are in place so that Antwerp’s old waste incineration plant, which was planned in 1975, can be replaced by a new building by 2027.

“Usually only technicians can make sense of abstract emission values,” says Moulaert. So ISVAG created an independent and international pool of experts to assess its plans.

Their task was first to examine the existing plans for alternatives and, wherever feasible, to work out ways of implementing these.

The idea behind this was to ensure that no one objecting to the project would be able to say there would have been an environmentally or economically better solution that the operators hadn’t considered.

“But if we show that burning the waste of one million people in our plant generates as much particulate matter as heating 48 households with a wood or pellet fire in an annual comparison, then it becomes clear to ordinary people how clean our technology actually is.”

Extracts from the Berl report

In New Zealand, landfill is the predominant method for waste disposal. We estimate that in 2018 New Zealand generated 17.6 million tonnes of waste, of which 12.7 million was disposed of in landfills including farm dumps.

Some areas are facing urgency to invest in new solutions as the waste flow has increased, severely shortening the projected life of existing local landfill.

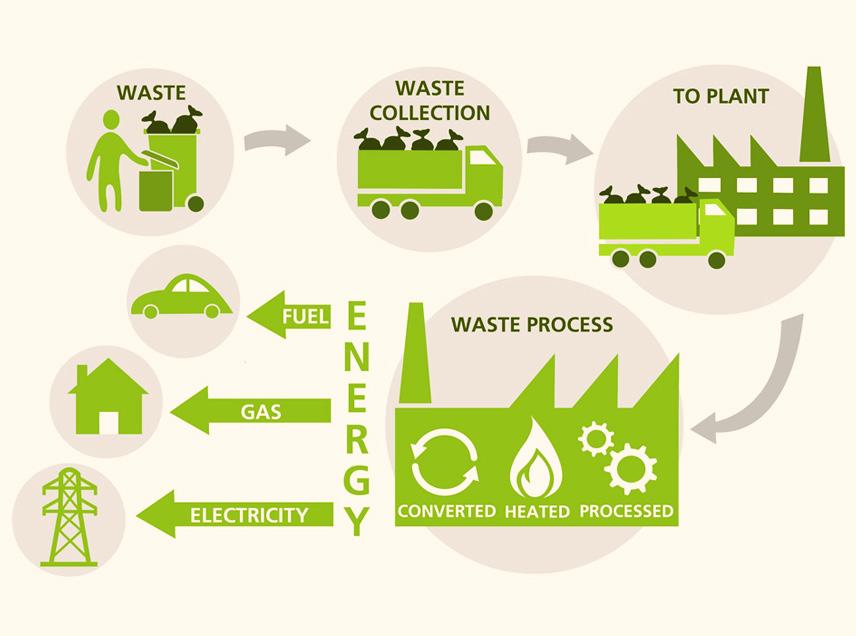

One solution proposed to reduce the amount of waste going to landfills is Waste to Energy (WtE). WtE is the process where waste is incinerated to generate heat and electricity.

In May 2018, the Ministry for the Environment through the waste minimisation portfolio adopted a circular economy policy approach. A circular economy is about a shift away from an increasingly unsustainable, ‘take, make, dispose’ economic model which relies on large quantities of cheap, easily accessible materials and energy.

A circular economy is an alternative to the traditional linear economy. In a circular economy, resources are kept in use for as long as possible. Maximum value is extracted from resources whilst in use and end of life products are regenerated, repaired or recovered. It is about making growth sustainable and creating an economy which maximises the use from its current resources, rather than continuously extracting more from nature.

The Ministry for the Environment (MfE) considers transitioning to a circular economy will reduce waste and associated pollutants, protect and restore natural

capital, and help address issues including climate change and water quality.

The introduction of WtE could affect New Zealand’s efforts to move to a circular economy.

By creating an alternative to landfills, WtE could affect efforts to reduce the creation of waste including reuse, recycling, and reprocessing. Despite being promoted by some as renewable energy or recycling, the European Commission have mapped various WtE methods against the waste hierarchy and found that this is not the case.

Anaerobic digestion of organic waste where the digestate is used as fertiliser is considered recycling.

Incineration and co-incineration with a high level of energy recovery and reprocessing of waste into solid, liquid or gaseous fuels is considered recovery.

Incineration and co-incineration with limited energy recovery is considered disposal in the same way as current landfill with gas capture.

Pressure on recycling operations is also impacting the transition towards a circular economy.

In 2018, 4.9 million tonnes of recyclable material was recovered from the waste stream.

Recycling operations within New Zealand are limited and New Zealand’s ability to export waste has been reduced by the Chinese government’s decision to severely limit the volumes and types of waste they will accept. In 2018 New Zealand exported $573 million worth of waste. Local authorities are now reducing recycling services that are no longer affordable, due to declining prices for recyclable materials.

WtE has been promoted as a solution to this increased need to dispose of materials within New Zealand. The decision to adopt WtE as a disposal method for New Zealand’s waste will need to consider more than the relative financial cost.

Waste companies and local authorities considering WtE will weigh up other factors such as environmental and reputational impacts, and public acceptance of waste incineration.

Disposal of waste through any method creates emissions, both of greenhouse gases and other toxic substances. This sum effect of WtE could be either positive or negative depending on the energy market, WtE technology employed, regulations around the operation of the WtE facility, and the standard of ongoing maintenance and management.

Likewise, toxic emissions can be managed though use of technology and operations practices, however WtE creates some amount of toxic ash which has to be disposed of, most likely into landfill.

There are steps the government can take to reduce the risk of WtE projects hindering efforts to transition to a circular economy.

We recommend that MfE in partnership with other relevant authorities including the Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment and the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority carry out further research into other types of WtE and should set standards based on international best practice.

This would enable the government to consider the impact WtE will have on New Zealand’s waste goals. There should be tight controls over waste that is used by WtE facilities, with penalties for non-compliance to discourage the incineration of materials that should be put back into the circular economy.

Alongside setting minimum standards, MfE should improve data capture of the waste sector to enable informed decision making by central and local government and those who are proposing WtE facilities.

Waste disposal facilities are significant investments that take a number of years to progress from concept to completion. Accurate forecasting of future waste volumes will minimise an under or over supply of waste disposal facilities.

Knowing what the future looks like will enable better controls over the supply of waste disposal and the impact this has on the circular economy.

Finally, MfE and the government should continue to promote incentives to reduce the creation of waste and increase reuse and recycling. Expanding domestic recovery, reuse and recycling infrastructure would support this, while reducing reliance on overseas destinations to manage our waste.

Increased domestic recycling would also reduce the need to import virgin materials, further diminishing the waste stream.