12 minute read

Nature

The Fens of South Cambridgeshire

Advertisement

Melbourn is fortunate to have a number of nature reserves on its doorstep – Stockbridge Meadows in Dolphin Lane, Melwood in Meldreth (both regularly featured in the magazine) and Fowlmere RSPB Nature Reserve. What some residents may not be aware of is that a small part of the RSPB reserve sits with in the parish of Melbourn.

In 1977 the RSPB purchased 65 acres of land which was part of a former water-cress farm, from money raised by the Young Ornithologists’ Club (YOC), known today as the Wildlife Explorers.

Interestingly, before the area became a reserve, the owner Hugh Stovin, a golf course developer had plans to develop it into a wildlife park, and sought planning permission to adapt the land. His business partner was to be a wellknown British naturalist, author and broadcaster of the 70s, Grahame Dangerfield.

Dangerfield had a private menagerie of largely British wildlife and several species from around the world including: servals,

A family of swans at one of the former water-cress beds on the reserve. Water-cress can be seen growing across the bottom and up along the lefthand side of the picture. Also on the left, a concrete walk-way being used by the swans, a left over from the days of water-cress production. On the right in the centre you can just see the ripples from one of the natural springs eagles, falcons, owls and Arctic foxes, to name but a few. However, planning permission for the new venture was refused in 1972, partly because the area had been designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).

The old water-cress beds today, consist of marshy grassland, open water and reed-beds, and is a veritable habitat of fauna and flora. Over 300 varieties of plants have been recorded at the site and well over 200 species of animals, including birds (resident and visiting), dear, fish, and reptiles.

A valuable source of clear-water coming from underground chalk aquifers via springs feeds into the various water courses and into the River Shep, a rare chalk stream, providing the ideal habitat for a variety of creatures to breed and thrive. It is home to brown trout and water vole.

With so many varieties of birds and animals visiting the site or just passing through, there is usually a good chance to find some interesting wildlife. In spring and summer, the reserve is one of the best places in the East of England to hear and see the rare turtle dove. The water vole, another rare species can sometimes be seen sitting on the bank feeding.

The history of the Moors

It’s hard to imagine today, that the land between Melbourn and Fowlmere was once a great expanse of marshy land, swamp and open water. Fed by natural springs and dominated by grasses and reeds, the area was said to have covered over 300 acres and was known as Melbourn and Fowlmere Moor.

Much of the marshland sat within the parish of Fowlmere and because of its similarities to the Fens north of Cambridge, it was often referred to by naturalists visiting the site as ‘Fowlmire Fen’ (a name that has stuck to this day). Although it’s difficult to visualise how this vast area of land would have looked, the RSPB reserve with its mere, marshy areas and reed beds is a good if not small example. To give you some idea of the amount of water that was possibly there, a document from the early 1800s referred to the area as The Lakes.

The land would have provided food for the locals not only fish such as carp, pike, trout and eel, but various wildfowl, rabbits and pheasants. It also provided employment for men and women. Some of the jobs were unusual and included fowling, leech gathering and frog fishing.

The marshes were abundant with wildfowl, so it is somewhat ironic that given the protected nature of the site today, the area

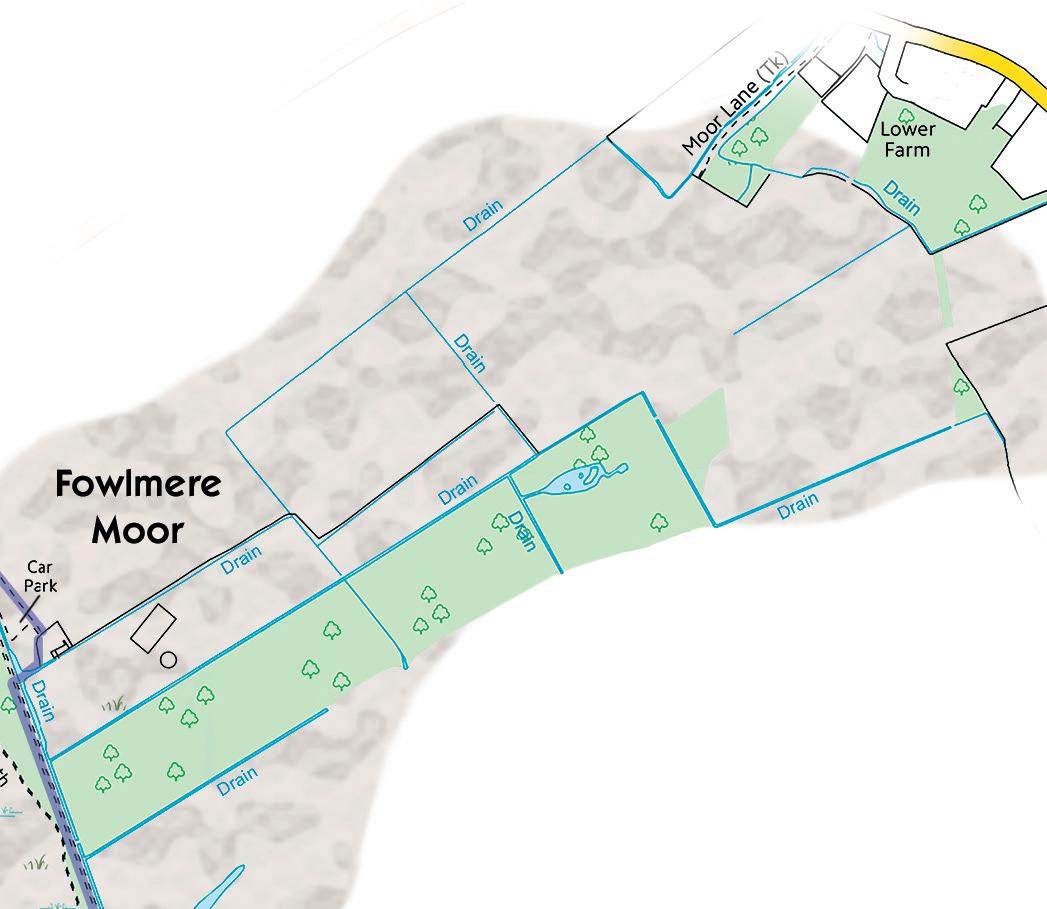

Parish boarder RSPB Nature Reserve Bran Ditch The Moor Fowlmere

River Shep

Melbourn and Fowlmere Moor once a great expanse of marshy land, swamp and open water. As you can see on the map below, the Moor stretched up into Shepreth (known as

Dunsbridge Gate) across into Meldreth (Rights

Moor) and back into Melbourn to the Moor where the village college stands

Melbourn

Spring source of the River Shep RSPB land from 1977 These maps have been created using a number of sources including a distorted 19th century etched printing plate. The area highlighting the Moor is to offer an idea on how it could have covered the surrounding countryside. Due to the quality of the image of the etching the area shown is not accurate

Meldreth

Rights Moor

RSPB land from 1985

Shepreth Dunsbridge Gate

Fowlmere Moor

Fowlmere RSPB Nature Researve

Melbourn Moor Fowlmere

Melbourn

once attracted people from all over, to shoot the wild geese, ducks and waders. Eighteenth century documents suggest that the birds from the Moor were sold on Cambridge market and sent to markets in London.

Locals also earned a wage from taking the ‘young gentleman’ from the University of Cambridge out in their punts for a day’s shooting. If the students were unlucky on the day, the locals would happily sell them a few birds, so they could at least show their fellow students how good they were at the sport. Below is a poem from the late 1800’s on the ‘fowling’ on the Moor.

The Gaffer’s Lament

The Girt Moor wor a Moor – an’ glory to boot

Nuff’n like it in England and Wales

Wi’ its duck, swan, geese, widgeon, teal, tern and coot

Which sportsman came ’undreds o’ miles for to shoot

And its frogs, wot were called Nightingales. The marshes also provided the perfect breeding ground for medicinal leeches. Used in blood-letting, they were in growing demand in 19th century. Locals were employed as leech gatherers to collect leeches by wading around the swamp, baring their legs whilst the leeches attached themselves. After about twenty to thirty minutes, after the leeches have gorged themselves they dropped off and were put into containers. The workers were poorly paid and many suffered from infections spread by the leeches and the effects of blood loss, since it would take at least 10 hours for the wounds to heel.

Following an encounter with a leech gatherer, William Wordsworth the poet described their work in his poem Resolution and Independence, written in 1802.

He told, that to these waters he had come

To gather leeches, being old and poor:

Employment hazardous and wearisome!

And he had many hardships to endure:

From pond to pond he roamed, from moor to moor;

Housing, with God’s good help, by choice or chance,

And in this way, he gained an honest maintenance.

He with a smile did then his words repeat;

And said, that, gathering leeches, far and wide

He travelled; stirring thus about his feet

The waters of the pools where they abide.

“Once I could meet with them on every side;

But they have dwindled long by slow decay;

Yet still I persevere, and find them where I may.”

The Mere at the Reserve today. There was a time when the Moor was a great expanse of marshy land, swamp and open water

Amongst the common frogs and toads found on the Fen, there was once a rare species known as the Edible Frog. Rare because this particular species was said to be exclusive to these marshes and one other site in Norfolk. They were in abundance on the Moor and because of their constant chatter, a call that was not the typical croak, they were known locally as Cambridgeshire Nightingales. They were described by one local as “much like other frogs, only girt big fellers and more yellow on the back”.

The species in the marshes was confirmed in 1843 after a specimen was sent to the British Museum, although documentation suggests they had been around the Moors for at least a century before. However, their ‘official’ confirmation was academic as a few years after their so-called discovery, the species was wiped out from the area when the marshes were drained.

Whether the frog was indigenous or introduced to the area is unknown, but one early suggestion was that monks coming over from Italy to collect rent due from a Priory in Chesterton in Cambridge, brought the frogs with them.

They were a staple diet for many throughout much of Europe, encouraged by the Catholic Church, when in the 13th century it decreed that the frog, much like the duck and other water fowl ‘could not possibly be meat’ since their ‘natural habitat was as much terrestrial as aquatic’. This allowed the ‘non-meat’ to be eaten during Lent and on Fridays, when all other meat was banned. In France, the frogs were given the nickname ‘Alouettes de Carême’ (known in English as Lenten larks).

Frogs may not be a typical British culinary delight today (unless you visit a French or Chinese restaurant), but they were many years ago when people would have little choice but to eat whatever was available. Thomas Coryate, a 17th century writer of travel books when on a visit to London wrote “I did eate fried Frogges in this citie, which is a dish much used in many cities of Italy.” In 1602, Thomas was said to have introduced the English to ‘Frog Pie’. However, it appears we have been eating frogs for some time. At an archaeological dig in Amesbury in Wiltshire in 2014 cooked bones of frog legs were discovered, dating back almost 9000 years.

Fortunately, common frogs and common toads can still be seen at the RSPB reserve – just not the edible one!

Water-cress growing

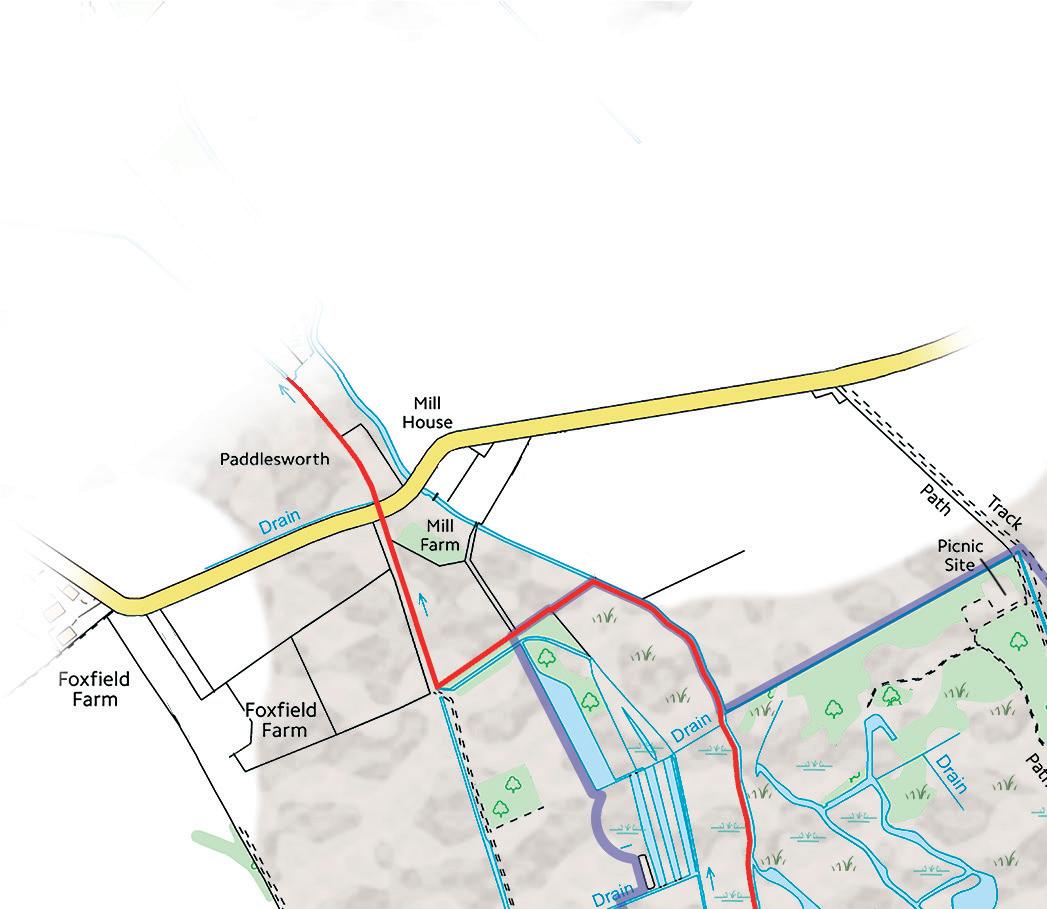

By 1847 much of the Moor had been drained to make way for agriculture. The area around the RSPB reserve was difficult to drain and so the land was later given over to water-cress production. The natural fresh water springs at the site provided the perfect environment. To improve the water flow, boreholes were driven into the ground to the natural aquifers to create additional springs. By the 1960s there was over 100 acres of water-cress beds.

The water-cress was washed and packed on site and taken to Shepreth station and then onto Covent Garden Market in London. Production continued on part of the site until the 1960s when it was abandoned. The area became overgrown with reeds and it was this land that was sold to the RSPB in 1977.

Water-cress continued to be grown around Black Peak up to the early 1980s when the water flow from the springs became a problem. Despite the introduction of a new pumping system to feed water from a borehole to Black Peak, production ceased. In 1985 the remaining land, around 35 acres was also sold to the RSPB. The small water-cress washing shed can still be seen at the reserve.

Large parallel water channels were dug close to the water-cress beds to create a trout farm and a fish breeding pen. The channels can still be seen today.

The trout farm, large water channels were dug close to the water-cress beds

Water-cress production at Black Peak in the early 1900s. Photograph Cambridge Collection

Bran Ditch

The importance of the land around the springs at Black Peak is proven by its occupation throughout our history. From the southern edge of the RSPB reserve and close to the springs is an Iron Age enclosure. It would have been a small settlement surrounded by a bank and ditch. It’s from here that Bran Ditch (also known as Heydon Ditch) begins. This Anglo-Saxon defensive ‘wall and ditch’ runs alongside the Iron Age enclosure and forms the parish boundary between Melbourn and Fowlmere. It extends for 5km in an almost straight line to Heydon. It was the first of four defensive walls built between Black Peak and Newmarket.

Bran Ditch. There is little to see today of the Anglo-Saxon defensive ‘wall and ditch’. This photograph looking south towards Heydon shows Bran Ditch as a slight ridge on the right.

Excavations carried out at Black Peak and on Bran Ditch revealed an Iron Age ditch and a Roman settlement and cemetery beneath the dyke. Finds include pottery sherds and a beehive quern. This site would have had links to the Roman garrison said to be close to Portway where complete Roman flagons and bowls were found.

A Roman flagon, bowl and quern found at the Roman settlements near Black Peak

During excavations at Black Peak over 50 Anglo-Saxon bodies were found buried, mostly men but some were boys. It was suggested that a massacre or execution had taken place as the victims had been killed in a gruesome fashion. (See A Glimpse into Melbourn’s Past pp.14–15 for more information.) As a point of interest, there is no information that explains how Black Peak got its name. However, in the journal The Zoologist published in 1847, one naturalist visiting the Fen spoke of the problems with the Springs, “… the rise of water is not sufficiently rapid to prevent black mud accumulating at the bottom”. Just a thought! Peter Simmonett

References The Zoologist – A Monthly Journal of Natural History (1846-7); Handbook to the Natural History of Cambridgeshire (1904); Meals Medical with Herbal Simples of Edible Parts (1905); A Mere Village – A history of Fowlmere Cambridgeshire (1993); A Glimpse into Melbourn’s past (2004); Fowlmere RSPB Nature Reserve a Wildlife Oasis. Leslie Price (2013)