.

The Comfort Women System involved forced coercion.

Can architecture be used as a vehicle for apology?

Done by Melissa Chong

Thank you Alba Adrian Amasha Becca Haotian Helen Jim James Josh Kun Michael Marijke Mama Nick Papa Qian Ruby Sam Sean Shalini Sharleen Shijie Shirley Thao Yidong Yifei Yoyo Yuyang Zidong

Research Question Research Statement

Elaboration of Thesis Proposal - PrefaceThe First Encounter

Brief Introduction to the Comfort Woman System Post War Response - Part 1 -

Existing Comfort Women ‘Memorial’ Statues

Statue’s Position, Depiction, Programmatic Implications & Associated Events Statues Depiction of Agonsim Statues’ Ineffectiveness Reflections

- Part 2Dissecting the ‘Victims’ 7 Demands’ Textbooks as a Medium - Part 3 -

Deconstructing Agonism

Precedents // Presence of an Opposition Precedents // Aggression to Direct Attention Precedents // Irresolvability

Brief - Part 4Summary

Existing Site

Presence of an Oppostion and Irresolvability Aggression to Direct Attention

- Reflection- Bibliography-

.

Could architecture be used as a vehicle for apology? -

Since 2011, a series of comfort women ‘memorial’ statues have been erected to urge the Japanese government for a sincere apology. As of now, this objective has not been met.

Instead, these statues have become a source of geopolitical tension.

Although these statues have been successful in garnering an indirect confession from the Japanese government, its agenda continues to be misconstrued due to it vague curation, coupled with the distorted objectives perpetuated by activists. As a result, victim stories continue to be misused.

In response, this thesis will readdress the statues’ agonistic approach by developing an architectural response that narrows the range of interpretation, in an effort to clarify the victims’ agenda

Architecture cannot fully resolve problems.

However, architecture can provoke.

In “Design Activism for Whom?”, Randolph Hester claims ‘Every design action is a political act that concretises power and authority’. (Hester, 2005) In this, he discloses the authoritarian-nature of all design outcomes - one that is forcefully participatory. The mere existence or absence of a material object in space, provokes thought, which in the act itself, is a form of participation, whether it be conscious or subconscious. However, despite meticulously prescribing an object’s programmatic implications, participation can only be ‘forced’, and never controlled. As such, architecture may never fully resolve problems, but could only act as a cursor.

Since 2011, a series of comfort women ‘memorial’ statues have been erected to urge the Japanese government for a sincere apology. However, these objectives were never met. Instead these statues have become of a source of geopolitical tension, where the Japanese government has persistently demanded for its removal. As a response, an embassy was demolished, a statue went missing and another was formally removed. Despite the statues’ failed attempts at attaining an apology, the statues were successful in revealing a truism, where ‘not all problems can be resolved’. Though not intended, these statues are a reflection of agonism in architecture. Coined by Chantal Mouffe in “The Democratic Paradox”, agonism is a social theory that uses conflict to bring awareness to an issue.(Mouffe, 2000) Unlike pluralism which introduces an opposition to achieve consensus, agonism introduces an opposition to maintain conflict. For agonism, this tension is valued as it blatantly admits that ‘most conflicts are not fully resolvable” and it indirectly brings awareness to the protagonist. Contextually, these statues use conflict to conclude that ‘a sincere apology may never be attained’. To arrive at this conclusion, these statues amplify the protagonist’s stance - the denial of forced coercion in military comfort women stations. Although no direct acknowledgement was received by the Japanese government, the design decisions that reflect this publicised denial indirectly reveals ‘the existence of forced coercion in military comfort stations’.

Despite shedding light on the protagonist’s stance, these statues were not as effective because of its widened-range of interpretation.

Its association to a ‘memorial’ glorifies the victims as ‘heroes’, which does not align to the connotations nuanced in the victim’s personal recounts.

Its ease of dismantle reflects the government’s view of the statue - a pawn for the political economy of diplomacy.

Most importantly, its visual depiction portrays the statue as an opportunity to promote personal opinions and nationalistic ideals through the ‘monopolisation of pain’.

Part 3 will focus on generating an architectural brief. It will begin by deconstructing the concept of agonism into its three themes - presence of an opposition, aggression to direction attention to the protagonist and the irresolvability of conflict. Subsequently, it will explain how the statues fail to depict the theme ‘aggression’ successfully. With this aggression will be further deconstructed into 3 design tropes - visual presence, methodology and programmatic implications.

With these unreflective and uncomfortable programmatic implications, this thesis will develop an alternative response that aggressively narrows this range of interpretation, such that it specifically addresses the victims. This would be carried out in 4 parts.

Part 1 will interrogate the honesty of these statues. Using the statue in Seoul as a point of departure, this research will analyse the statue’s position, depiction, associated events and programmatic implications through detailed line-drawings. Subsequently, it will explain the statue’s depiction of agonism; by documenting the consequences of erecting the statue in the Philippines. With this, Part 1 will conclude by explaining the statues ineffectiveness.

Part 2 will analyse the victims’ underlying wishes. Using a bottom-up approach, this research will dissect the structure and terminologies used in the ‘Victims’ 7 demands’. Through publicly available first-hand interviews and documentaries, these findings will be compared to the victims’ sentiments to determine its consistency. Lastly, this research will explain the selected mode of action, as a response to the statues ineffectiveness.

‘The presence of an opposition’ is depicted as a space that questions the status quo by provocation. By comparing Daniel Libeskind’s ‘Jewish Musuem’ and Rachel Whiteread’s ‘The Nameless Library - Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial’, this research will discern which mode of participation is more contextually appropriate - experiential participation through physical bodily movement or participation through non-didactic platforms. ‘Aggression to direct attention’ is depicted through the rigorous clarifying of scope. Riding on the radical, ‘Paper Architecture’ is explored by comparing two contrasting utopiasthe ‘opportunistically revolutionary’ and the ‘critically dissident’. For this, Lebbeus Wood’s ‘Einstein Tomb’ and Brodsky & Utkin’s ‘The Crystal Palace’ will be analysed. After narrowing the thesis’s scope to the ‘critically dissident’, aggression will be explored spatially through Jochen Gerz’s ‘Monument Against Facisim’ for visual presence, Ai Wei Wei’s ‘Sunflower Seeds’ for methodology and Canberra’s ‘Tent Embassy for programmatic implications.

“Irresolvability’ is depicted through the juxtaposition of unresolved conflict and the ambition to resolve. As such, this research will study how Junya Ishigami’s ‘Art Biotop Water Garden’ uses deliberate design decisions and construction methodologies to affirm the above.

Part 4 will focus on generating an architectural response. It will begin by explaining the existing site conditions. Using the parameters derived in Part 3, it will then discuss how ‘the presence of an opposition’ and ‘irresolvability’ is depicted through its design decisions. Lastly, in response to the statues’ ineffectiveness, it will explain how ‘aggression to direct attention’ is achieved through its visual presence, methodology and programmatic implications.

- Preface -

It happened in 2018.

I was on an exchange program in Tokyo for 6 months.

During a farewell party, I told my friend David that I would be staying in APA Higashi Nihonbashi before heading off to Osaka to meet my family.

“Its that hotel chain, isn’t it?

The one that has ads in the metro? The one with the pink lady in sunglasses or the guy in purple with leopard prints?”

I nodded.

“You should check out their books! The one in green, it’s probably behind some pamphlets on the shelves? You can’t miss it !”

From there, my curiosity grew.

Found it.

This book was an uncomfortable read.

Page 6 denied the Nanjing Massacre.

Page 8 denied the existence of the Comfort Women System.

Page 11 denied Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour.

This book has uncomfortably denied all the stories I’ve heard growing up.

The term ‘comfort women’ is derived directly from its Japanese equivalent, ‘ianfu’ meaning ‘consoling woman’. (Ward & Lay, 2018)

Despite this widely-known association, this term linguistically obscures and warps the conditions these victims were under. As such, this research will strongly and repeatedly refer to these victims as ‘victims of the Comfort Women System’.

Parameters -

The ‘Comfort Women System’ refers to an organised system of sexual slavery that is managed by the Imperial Japanese Military during WWII. This system involved coercing young women into providing sexual services to Japanese troops in formal ‘comfort stations’, located in both Japan and their occupied territories. Most of these women are from formerly-occupied territories - China, Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Myanmar, Malaysia and Singapore. As of now, little is known about the number of Japanese women involved and their backgrounds. (Naoko, 2016) As such, the premise of this research will be limited to the identified victims from these occupied territories.

The gravity of this situation should not be confined to statistics. Their experiences are immeasurable, unquantifiable, and should not be compared.

Mapping the Location of Comfort Stations

derived from victim testimonies, Japanese soldiers’ testimonies and journals , official and military-related documents and witness testimonies and others (Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace)

Dots, not to count. Dots, to show existence.

“Even though we didn’t want to go, they forced us. When I asked my mom where I was going, she told me that because of WWII, I was going to a factory that made soldier’s uniforms. Because they were short staffed, they apparently needed more young women. They also promised my mom that I’d return once I was old enough to marry. So they said I had no reason not to go.”- Kim Bok Dong, Victim. “According to testimonies given by Korean “Comfort Women” they were forced to get their uterus surgically removed before coming to China to avoid the posibili ty of pregnancy - Xu Ming Ting, Former Deputy Director Wuhan City Library.“Then, we would have lost everything, and gotten exiled from Korea. That’s how they blackmailed us. If the Jap anese have confiscated all our belongings, how was our family supposed to love? - Kim Bok Dong, Victim“These women would have needed more than two weeks to heal which suggests that the Japanese had prepared for the establishment of these institu itions for a long period of time. - Xu Ming Ting, Former Deputy Director Wuhan City Library. “The Comfort Women System was set up by the Japanese military, the Japanese government.”- Dr Su Zhi Liang, Director of the Chinese Comfort Women Research Centre. “I was stationed from Guangdong to Hongkong, Malay sia, Indonesia, and Singapore.”- Kim Bok Dong, Victim. “Japa nese solderis came to my village and asked me something in their language. I didn’t understand. He got his sword and stabbed me here. Look at my facial appearance.”- Lola Frias, Victim. “There were three Japanese solderis riding on a truck. They took me to the garrison.” - Lola Hilaria Bustamante, Victim. “A few days later, the twon foreman came to our house and told me ‘If you go to work at the Thousand-Person Stitches factory in Japan, for just two to two and a half years in exchange, your father will be released from the prison the same day you leave for Ja pan. I believed him. ” - Seo Woon Chung, Victim. “ I was taken to Semarang, Indonesia through Jakarta. I ended up in Sema rang with 13 other girls. I realised I was not in Japan, but in another country farther away.”- Seo Woon Chung, Victim. “In March 1938, a Japanese policeman in army uniform holding a long sword came to the store. He said a job that pays well was waiting for me. I was taken to Pyongyang.” - Park Yong Sim, Vic tim. “When I was 14 years old, my father was arrested by police because he did not visit Japanese shrines. I was busy caring for my younger brothers and keeping the house, and had no idea of going to school.My father could speak Japanese well and told a lie that from now on he was going to visit Japanese shrines with his followers. Liberated, he went home. He cured the burn on his leg which the police inflicted. Then the police came to arrest him again. It was 4 o’clock in the morning. Father was praying in the church. I sprang up and ran to the church.“Daddy, run away. The police are here again.” At that time around the church was surrounded by rice fields and vegetable fields. Close by was a Japanese village. He stopped praying and fled through the Jap anese village. He went through Taegu and arrived at Sengju to see his aunt, who hid him from police.” - Kimiko Kaneda, Victim. “At that time, my fiancée had been drafted by the Japanese mil itary and sent to the south. I was helping my father’s business at home. One day, the Japanese police called and told me to come because they had a job for me. They said that I would be pre paring meals and mending torn clothes for the soldiers. I did not want to go, but the police said that all men and women must come because the country was at war then and that everybody must follow the General National Mobilization Law. So I went to work.” - Taiwanese that preferred not to be named, Victim. “We were forced onto this open truck through cattle, and I remember we were so scared we were clinging you know to our little suit cases and clinging to each other and the truck stopped in front of the large door to colonial house and we were told to get out when we got into the house.” - Jan Ruff O’ Herne Victim. “ We started protesting straight away we said that we were forced into this you know that that they couldn’t do this to us you know I had no right to do this was against the Geneva Convention and that we would never never do this but they just laughed at us you they could do it was what they liked. ” - Jan Ruff O’ Herne, Victim. “The Japanese soldiers would pat our heads and ask how old we were. I was only nine then but some other girls were around fif teen. The Japanese soldiers would take those fourteen- or fifteen year old girls away. This happened several times, but I was very young and at the beginning I didn’t know where they were taken or what happened to them, until I saw one of the girls dead.”Lei Gui Ying, Victim. “We heard that the Japanese troops accom panied by local traitors has come to kidnap girls. All the women in the village ran desperately trying to escape. My cousins and I ran for our lives. We crossed a little river and hid ourselves behind a millstone in a villager’s courtyard, but the Japanese troops chased after us and found us. Later we learned that the Japanese troops have been looking for good-looking girls to put in their comfort stattion. Because my cousin and I were known for our good looks, we had been targeted. The Japanese soldiers tied our feet with ropes so that we could not run away. Then they had us loaded in a wheelbarrow, one one each side, where they tied us tightly with more ropes. They forced some villagers to push the wheelbarrow to the Town of Baipu. The ropes and the jolting of the wheelbarrow hurt like hell all the way.” - Zhou Fen Ying, Victim. “My mother heard about my capture and went to beg the Japanese soldiers to release me. She kneeled in front of them, holding me tightly so they could not drag me away.” - Lu Xiu Zhen, Victim.

BARBED WIRE FENCINGBARBED WIRE FENCINGMAIN GATEBARBED WIRE FENCINGBARBED WIRE FENCINGBARBED WIRE FENCINGBARBED

BARBED WIRE FENCING - BARBED WIRE FENCING - BARBED WIRE FENCING - LOCKED DOOR

“We got rice but it was like beach sand. We ate it with rotten cabbage leaves that were sprinkled with some salt and red pepper flakes” - Lee Ok Seon, Victim. “No sauce. We got this much (pal m size)”- Lee Ok Seon, Vic tim. “ Since we worked with very littel food or rest many people got sick and died.”- Lee Ok Seon, Victim. “There was a Korean girl who did all the cooking. The girls who serviced the men didn’t have to cook, clean or look after the fire. - Lee Ok Seon, Victim. “ At Gaotaipo Comfort Station, the girls were given 3 meals a day - usually rice with soy sauce, and on some rare occassion there was canned fish - but often not enough to eat.”- Lei Gui Ying, Victim. “Because we were only given two course meals a day, we were always hungry. I had to save that money and ask people to buy me food when I was starving. “Zhou Fen Ying, Victim. “The proprieter hired a Chinese man to cook us three meals a day, but the food was very bad and the amount was very small.” - Yuan Zhu Ling, Victim. “Even though we’ve been there for a while, it was still hard to stomach the food they gave us. We got steamed kaoliang and millet with kimchi radish leaves and cabbage. But everything was practically rotten.”Lee Ok Seon, Victim.

KITCHEN - DOOR - KITCHEN

“You know those steamed buns they sell at the mar ket? Every morning, we each got a small one. How are we supposed to last the whole day after eating one bun? We didn’t even get water.” - Lee Ok Seon, Victim. “We were taken to the dining room of the unit and made to sit on the floor.” - Kimiko Kaneda, Vic tim. “ For two days I was unable to eat anything. I was too frightened.” - Yuan Zhu Ling, Victim. “Our meals were prepared in the military cookhouse in the stronghold and sent down from Shizi-shan Mountain. We ate with the soldiers.” - Yuan Zhu Ling, Victim.

-MEALS - DOOR - MEALS

KITCHENKITCHENKITCHENKITCHEN -

“Anyway they told me to get inside where I was greet ed by a team of Army medics who examined my body. “-Kim Bok Dong, Victim “So the medics arrived and re vived us by pumping our stomachs...My stomach is per manently damaged. “ - Kim Bok Dong, Victim “At the end of the day, the medics would come to treat teh areas on our bodies that needed it.” - Kim Bok Dong, Victim “They injected us with shots, and told us to take medi cine.”- Kim Bok Dong, Victim “I woke up 3 days later. People told me that I was bleeding everywhere through my mouth and ears. ”- Seo Woon Chung, Victim. ” - Kim Bok Dong, Victim. “He was taken away by the military police and I was taken to the infirmary. My clothes were soaked with blood. I was treated in the infirmary for twenty days. I was sent back to my room. A soldier who had just returned from the fighting came in. Thanks to the treatment my wound was much improved, but I had a plaster on my chest. Despite that the soldier attacked me, and when I wouldn’t do what he said, he seized my wrists and threw me out of the room. My wrists were broken, and they are still very weak. Here was broken.... There’s no bone here. I was kicked by a soldier here. It took the skin right off... you could see the bone.” - Kimiko Kane da, Victim. “I remembered a Japanese perrson wearing white clothing came to check our bodies, including our private places. I didn’t understand what he was doing at the time, but I was very scared and my whole body shook when he checked me. The Japanese soldier also came to check me when I fell sicj in the comfort station. The old woman gave us some small rubber caps and told us to put one on the soldier’s penis when he arrived.”- Zhou Fen Ying, Victim“As soon as we entered the station, the proprieter orders us to take off all our clothes for an examination. We refused, but Zhang Xiu Ying’s husband had his men beat us with leather whips... The physical exam was over very quickly because none of us was a prostitute and no one had venereal diseases.”- Lu Xiu Zhen, Victim.

INFIRMARYINFIRMARYINFIRMARYDOORINFIRMARY

MEALSMEALSMEALS - - INFIRMARY - DOOR - INFIRMARY

“They made me take soldiers the day after I got there.”- Ha Sang Suk, Victim. “They climbed aboard planes to carry out sorties. Since we weren’t allowed near planes, we didn’t know how many there were or where they were headed. We onlysaw them take off or land. Sometimes I wondered: Would that plane fly over my home?”- Lee Ok Seon, Victim. “ In Peitan we got off the coach and entered a house, in which a number of women and girls were crowded. Near the house there was garrison of a Japanese regiment, which was always patrolling for enemies. On that day we were divided into groups of ten and I was sent with other girls to Zaoqiang. There, in a city surrounded by walls, was a unit of the Japanese army stationed.” - Kimiko Kaneda, Victim. “I’ve been in the camp for two year, they gave an order that all the young girls from 17 years and up has to line up in a compound these high military officers walked towards us and started to is up and down looking at all figures looking at our legs and it was obviously a selection process that was going to take place.” - Jan Ruff O’ Herne. “We were scared to death and couldn’t even cry. When I looked around, I saw about twenty girls were already there. ” - Zhou Fen Ying, Victim. “We were not allowed to step out of the stattion. There were two or three elderly women from the Town of Baipu who cleaned, delivered food and water and so on.” - Zhou Fen Ying, Victim. “However, this place was closely guarded by the soldiers and there was no way for him to rescue me.” - Zhou Fen Ying, Victim. “They searched high and low for good-looking women to comfort the Japanese soldiers. In order to meet the desires of the Japanese officers, they forced secen townswomen to form a comfort women group. These ‘Seven Sisters’ were Zhou Hai Mei (Sister Mei), Lu Feng Lang (Sister Feng), Yang Qi Jie (Sister Qi), Zhou Da Lang (Sister Da), Jin Yu (Sister Yu), Guo Ya Ying (Sister Ying) and me (people called me Sister Qiao). We became those Japanese troops’ sex slaves. They declared us set aside for special service to militrary officers. The ordinary soldiers, who were not allowed to touch us, assaulted the other girls of the town.” - Zhu Qiao Mei, Victim. “The building was very clsoe to military barracks . It was guarded by soldiers, but we were allowed to walk around the facility amd do things such as washing clothes.” - Lu Xiu Zhen, Victim. “As soon as we went ashore, we were taken to a temple by the Japanese soldiers. As a matter of fact, the Japanese army had already turned the temple into a comfort station. A Japanese soldier was standing guard at the entrance. I was frightened by the devilish looking soldiers and didn’t want to enter. By ow the girls and I realised that something was not right, so we wall wanted to go home.” - Yuan Zhu Ling, Victim. “But the Japanese soldiers forced us inside with their bayonets.” - Yuan Zhu Ling, Victim. “We were not allowed to go out. An armed guard always stood at the entrance watching the women. He would catch and beat anyone who attempted to escape. I was completely listless at that time, unable to think or speak properly. The only thing in my mind was going home, but there was no way for me to leave the house...We missed home so much, but we dared not run away.” - Tan Yuan Hua, Victim.

- CAVALRY - DOOR - CAVALRY -CAVALRY -CAVALRY -CAVALRY -

“Hundreds of soldiers were killed or injured everyday. They put out boards on the parade ground and erected tents over them. The dead were put in there. They laid out the injured there. The soldiers cried out in pain. We didnft give water to those who still had the will to live. We wiped their lips with a cloth soaked in alcohol, and gave them an injection to make them sleep. We gave two injections to the seriously wounded. After the morphine shot they would stop crying and sleep. When the morphine began to wear off they would grab at my clothes. They usually called me Kaneda Kimiko, but at those times they would call me Onesan (sister). “Onesan, please give me another shot!” I felt sorry for them, so I would inject them again, and they would sleep.” - Kimiko Kaneda, Victim. “The barracks held about 50 Japanese troops, who kidnapped dozens of young women from nearby villages to be their comfort women.” Zhou Fen Ying, Victim. “Many of the soldiers had two or three stripes on their epaulettes, so I guessed they were officers”. - Zhou Fen Ying, Victim. “The platoon chief ordered soldiers to watch us and not to let us go too far and we were not allowed to enter the barracks.” - Lu Xiu Zhen, Victim. “Be cause a traitor revealed my anti-Japanese activites to the Japanese troops, they treated me more viciously than they did to the other girls. During the day time the Japanese soldiers hung me up on a locust tree outside the cave and beat me, forcing me to admit I was a communist and to tell them who else in the villagewere CCP members. I gritted my teeth tighlty and refused to say anything.” - Hou You Liang, Victim.

“They asked me, “How old are you?”When they talked among themselves, saying Victim“ So scared, I was shaking in fear. 13 girls there.”- Seo Woon Chung, Victim. station manager gave us each a bundle” flower names and they were pinned on my Japanese flower name I just didn’t drag us away one by one” - Jan Ruff O’ a summer day and a lot of Japanese troops picking out good-looking girls and mumbling change into a Japanese robe that has large room. “- Lei Gui Ying, Victim. “Each given a number. The number was printed was about three cun long and two cun given based on the looks of the girls; I tim “They paid the old women with military pick girls.” - Zhou Fen Ying, Victim. “After each girl a Japanese name. I was named of about seven to eight square metres that Zhen, Victim. “The proprieter didn’t allow periods; he continued to let the Japanese make us take some white pills and tols them. We didnt know what the pills were. Yuan Zhu Ling, Victim. “From the first station, a Japanese soldier named Fujimura the head officer of the Japanese army bought tickets to visit the comfort station, after a while he requested instead the lived.” - Yuan

- HEADQUARTERS - DOOR RESTROOMSDOOR -

“Everyday I had to take 10-20 men. It hurt wouldn’t come out, they would beat me all paper wasn’t common then. So we tore old rags.”- Lee Ok Seon, Victim. “I never thought eventually he left the room and I was in total a little girls were there they were all there crying within”. - Jan Ruff O’ Herne. “All big tub of water for bathing.”- Zhou Fen in, first we had to bathe and then the Japanese bed next to the tub. Other than that the troops We were almost tortured to death; no form - Zhu Qiao Mei, Victim. “We girls who suffered to wash our bodies, but there was only a take turns using. There were dozens of comfort water was unbearably dirty by the end

LAUNDRY - LAUNDRY - LAUNDRYDOOR -

“In the daytime I sewed clothes and did night I died”- Taiwanese that preferred not on I was forced to wash the Japanese soldier’s the Japanese soldiers would come.”-

- STORAGE - STORAGE - STORAGE

CAVALRY -DOORCAVALRY

“They were giving out Malaria pills. I pills at a time froma medical office because Victim. “I remember sitting in the brothel this handkerchief out and I asked the other names on this handkerchief and they did I you know I wanted to have something solid all wrote their name on the handkerchief chief” - Jan Ruff O’ Herne, Victim.

BARBED WIRE FENCING - BARBED WIRE FENCING - BARBED WIRE FENCING - BARBED WIRE FENCING -

Spatial Planning of a Comfort Station in Zao Qing China

Plan drawn by Kimiko Kaneda, Victim. Testimonies taken from a range of victim interviews, documentaries and print sources.

DOOR - BARBED WIRE FENCING - BARBED WIRE FENCING - BARBED WIRE FENCING - BARBED WIRE

you?”When they found out that I was only 14, “Isn’t she too young?” - Kim Bok Dong, fear. Was just 15, I was.I was the youngest of Victim. “When we came out of the bath, the bundle” - Lee Ok Seon, Victim. “We will given the doors you know I can’t remember my even want to know about it they started to O’ Herne, Victim.“ I rememeber that it was troops came to Shanben’s house. I saw them mumbling something. Mrs Shanben told me to a bumpy sash at the back and to go to the “Each of the girls in the comfort station was printed in red on a piece of white cloth,which wide. People said that the numbers were was number one.” ” - Zhou Fen Ying, Vic military money to buy tickets before coming to “After the examination, the proprieter gave named Masako. Each of us was assigned a room that had only a bed and a spitton.”- Lu Xiu allow us a break even during our menstrual Japanese soldiers come in one after another. He us that there would be no pain if we took were. I threw them away like other girls.”days when I was imprisoned in the comfort Fujimura took a fancy to me. He was probably stationed in Ezhou. At the beginning, he station, as the other Japanese soldiers did, but proprieter send me to the place where he Zhu Ling, Victim.

HEADQUARTERSHEADQUARTERSDOORHEADQUARTERS

DOOR - HEADQUARTERS -

hurt so bad that I hid in the toilet When I all over. ”- Ha Sang Suk, Victim. “Toilet old clothing into strips to make menstrual thought suffering could be that terrible and total shock and then I got to the bathroom there in the bathroom all total hysterical and “All the women had to share towels and a Ying, Victim. “When we were first taken Japanese troops would rape us on the litte troops never took any hygienic measures. form of remuneration was ever mentioned.” suffered numerous rapes everyday needed a wooden bucket in the kithcen for us to comfort women at the station, so the bath of each day.” - Yuan Zhu Ling, Victim.

LAUNDRY - LAUNDRY - LAUNDRY

the soldiers’ laundry. It was easy. But at not to be named, Victim. “From that time soldier’s clothes during the day and at night come.”- Huang You Liang, Victim.

RESTROOMSDOOR -

“As soon as I sipped it, I felt my mouth was on fire at first. Later, I couldn’t feel my throat. But al three of us finished the bottle. …

All three of us were knocked un conscious. We would have died, had no one intervened. But because we were missing till evening, they started searching for us, and found us on the floor unconscious.”- Kim Bok Dong, Victim. “To stay back alive and come back home, I had no choice but to comply. And be cause we did what we were told, we weren’t beaten.”- Kim Bok Dong, Victim.

- ROOMS - ROOMS -

“After that, they told me to go to my dorm. I’m not sure if it was a big school or factory building, but it was a big space. There were many rooms where you could see everything from the outside. You can see people having sex”.- Kim Bok Dong, Victim. “ They stood in queues. ...If there’s a delay, the guy next in line starts banging on the door.” Kim Bok Dong, Victim. “Yes , just one after the other.” Kim Bok Dong, Victim. “We were ordered to provide service to as many soldiers as possible.

On some days we had to serve 40-50 men per day. Kim Bok Dong, Victim. “And the soldiers started to randomly grab and snatch each and every one of us. there were soldiers with girls here, over there, up there, ev erywhere. - Lola Hilaria Busta mante, Victim. “I can’t even count how many soldiers came in, especially during weekends, lining up, still in their uniform. There’s just so much to tell. ”Seo Woon Chung, Victim. “On holidays, they would line up outside our doors as if they were buying something at a store. We couldn’t just serve one soldiers.

STORAGE - STORAGE - STORAGE

managed to gather 40 of them.Two, three because he was Korean. ”- Seo Woon Chung, brothel and it was almost getting dark and I got other girls would they please all right their I wanted to have something of them forever solid to remember them base forever so they handkerchief and I embroidered all for this handker

LAUNDRYLAUNDRYSTORAGESTORAGESTORAGE

It was five , six in a row.” - Seo Woon Chung, Victim. “We had just finished our work for the day and were in our room com pletely exhausted when a group of soldiers barged in. Just like that. In front of my friends... I was raped like an animal.”- Lee Ok Seon, Victim. “They start ed to drag us away one by one, and I could hear all the scream ing, coming from the bedrooms you know and you just wait for your turn you know”- Jan Ruff O’ Herne, Victim. “The Japa nese troops came to the stattion about every seven days, and we were made to do other jobs when the soldiers didn’t come.” - Zhou Fen Ying, Victim. “Quite a few of them would pick me, and some came to my room regularly.”- Zhu Qiao Mei, Vic tim. “The next morning I saw a wooden sign hung on the door of y room with ‘Masako’ writte n on it. There were also similar plagues hung at the entrance of the comfort station. That morning a lot of Japanese sol diers were swarming outside of the temple gate. Soon a long line formed at the door of each room.” - Yuan Zhu Ling, Victim.

ROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMSROOMS

“That time when I was raped, six Japanese soldiers came. There were three available for the six. The three were sick because of opium smoking, They yawned when opium was needed, With my small size, there was no way I could resist the soldiers.””I was so small. He ripped my pants and threw them away. I yelled for Hasuro to come quickly,s creaming out his name. Seeing that I was shouting for help , he took out a knife, that was the bayonet for mounting on the rifle. He stabbed at my leg and blood splurted all over. I crawled to get awa. I passed out. That was the first time. - Madam Lei, Victim. “The first time, I got dragged into one of the rooms and beaten up a bit. So I had to comply. When the guys finished, I was bleeding badly because it was my first time. The bed sheet was soaked in blood.” - Kim Bok Dong, Victim. “We tried to figure out how to commit suicide. I heard people could die from drinking a lot of alcohol. But we needed money to buy some. Thankfully, I had KRW1 (USD 0.0008) my mom has given to me. That was a lot of money back then. My mom wanted me to use that money to buy food when I got hungry. I decided to use that money to kill myself. There was a cleaning lady who worked there. I called her over, handed over my KRW 1, and asked her to get me something strong that would knock me out for good. She came back with a massive bottle of Kaoliang wine (38%-63% alcohol). She told me to drink that, and have some water afterwards.” - Kim Bok Dong, Victim. “They used condoms. And used some lubricant. The lubricant made it easier for them.” Kim Bok Dong, Victim. “ But I did it so many times a day that I lost count. By 5pm, I couldn’t even get up. I couldn’t walk properly.” Kim Bok Dong, Victim. “Every night, we were raped. Because its not just one who will rape you in one night. Its two, three, four, or even more.” - Lola Narcisca Claveria, Victim. “I was taken into a dark room by two solders. They forced me to the floor and tied me up. One soldier held me down while the other raped me. They took turns. I don’t know how many more raped me. I passed out. When I woke up, my body was covered in blood.” - Lola Pillar Galang, Victim. “ I resisted, kicking, pushing. Then the soldiers injected me with opium. So I became addicted. ”- Seo Woon Chung, Victim. “I swallowed 40 pills at once. But even dying, I couldn’t even kill my self. ”- Seo Woon Chung, Victim. “He ran his sword over my body starting at my neck, right down my body, right between my legs, and just played with me like a cat would do with a mouse; until my whole body was just with total fear. Until he eventually brutally raped me. I thought he would never stop.” - Jan Ruff O’Herne, Victim. “Girls have a thing called a hymen. Imagine how I felt. When mine ripped. Before I could get married or see the face of my husband. It was awful. I bled so much. I felt so dirty. Thats why so many girls try to kill themselves after rape. I wanted to die.”- Lee Ok Seon, Victim. “How did I feel? I felt as if we were taken here to be killed. I could not but weep. No one talked. All were weeping. That night we slept there and in the morning we were put in those rooms. Soldiers came to my room, but I resisted with all my might. The first soldier wasn’t drunk and when he tried to rip my clothes off, I shouted “No!” and he left. The second soldier was drunk. He waved a knife at me and threatened to kill me if I didn’t do what he said. But I didn’t care if I died, and in the end he stabbed me. Here( She pointed her chest).”- Kimiko Kaneda, Victim. “I put up an enormous fight but he just dragged me to the bedroom and as I said I’m not I’m not going to do this and he said well I will kill you if you don’t give yourself to me either kill you”- Jan Ruff O’ Herne, Victim. “He got out his sword andI went on my knees and to say my prayers and I felt God’s very close I wasn’t and I felt God’s very close I wasn’t afraid to die and as I was bringing me he had no intention of killing me of course he just you know threw me on the bed he got hold of me threw me on the bed and just told off all my clothes and just brutally raped me and I thought he would never stop.” - Jan Ruff O’ Herne, Victim. “ You come to his stage whether you think I’ve tried everything what can I do what can I do next I cut off all my hair I thought if I make myself look as ugly as possible nobody will want me and I looked absolutely horrible really ugly and the other girls they said Yanni what have you done what have you done I said well perhaps they will want me now it turned me into a cu riosity object and they wanted me if and well because I was the girl that that cut her hair off that you know that the bald girl you know we all want the bald girl it did just the opposite effect for some reason just the opposite effect for some reason or other you know so didn’t do me any good at all” - Jan Ruff O’ Herne, Victim. “The soldier became very angry when he saw me crying. He pushed his bayonet against my chest, snarling in a low voice. I thought he was going to kill me and I almost passed out. The Japanese soldier then raped me.”- Zhou Fen Ying, Victim. “I cried everyday, hoping my husband would free me from this place.”- Zhou Fen Ying, Victim. “The Japanese officers made me follow their orders. If I obeyed they sometimes gave me a small gift, but if I showed even the slightess unhappiness they would yell at me. I was forced to do whatever they told me to.” - Zhou Fen Ying, Victim. “When I was first abducted by Japanese troops I was already pregnant, but the Japanese officers raped me despite the baby in my belly. And merely two months after I birthed the child I was again subjected to frequent rapes. I has a lot of breast milk at the time, so the officers Senge and Heilian would suck my breastmilk dry every time before raping me. Afraid of being killed, I had no choice but to put up with these atrocities” - Zhu Qiao Mei, Victim. “ Each Japanese soldier usually spent thirty minutes in the room. We couldn’t get any rest even at night because the military officers often spent a couple of hours, sometimes the whole nigth, at the station.” - Yuan Zhu Ling, Victim. “They forced me to have sexual in tercourse with a Japanese military man. I was so young at the time but was britally raped. The Japanese man spoke a lot, but I didn’t undertsand what he was saying and I didint want to listen either. He beat me if I did not follow his orders.” - Yuan Zhu Ling, Victim. “The Japanese soldiers raped me day and night. Sometimes two or three soldiers entered the room together and gangraped me. They beat and kicked me when I resisted, leaving wounds all over my body. Later the soldiers came less often at night, perhaps disgusted at the purulent wounds on my body.”- Huang You Liang, Victim.

BARBED WIRE FENCING - BARBED WIRE FENCING - BARBED WIRE FENCING - BARBED WIRE FENCING

BARBED WIRE FENCINGBARBED WIRE FENCINGBARBED WIRE FENCINGBARBED WIRE FENCINGBARBED WIRE FENCINGBARBED WIRE FENCINGBARBED

“I saw my father and brother get tied up on a pillar. Then, the sol diers got a bayonet and started to skin my fatehr alive. Standing there, watching them get tortured to death... I felt liek dying, my self.”- Lola Pillar Galang, Victim. “Japanese troops gathered all the men and boys of the village. They castrated and gunned them down right before our eyes. Then they burned their dead bodies en masse.”-Lola Lita Vinuya, Victim. “They had put up an electric fence around teh airport to stop people from escaping. We had no chice but to work till we dropped dead. There was no way out.”Lee Ok Seon, Victim. “In Singapore, after Japan lost the war, the Japanese soldiers tried to cover up the existence of these comfort stations by turning us into nurses at the army hospitals. So I worked as a ‘nurse’ for about a year.” Kim Bok Dong, Victim. “The sol diers buried those girls like they buried dogs, No funerals. ”- Seo Woon Chung, Victim. “I felt as if I was dead. I wished to flee away, but I did not know the way. Soldiers were standing at the gates. If you fled, you would be shot. I was too young. I did not know any thing..”- Taiwanese that preferred not to be named, Victim. “One day we were told to pack or belongings again and we were there put in the transit camp I was there you know that was my mother and my two younger sisters and to see my mother again you know after all that time and my mother looked at my bald head you know and she feared the worst then that first night I couldn’t even talk or say any thing to her I just I can feel it now laying in my mother’s arms you know in the in the hollow of her arms you know so arms around me and she just stroked my head you know she just kept stroking my bald head and I’ll just lay there in the safety of my mother’s arms and and we didn’t speak we just later and then the next day I told her what had happened to me and so did the other girls who had all these these girls with all these mothers you know and and the mothers just couldn’t cope with the story this happened to their daughters you know it was too much for them they couldn’t cope with it and they we were only ever to tell our mothers just once and it was never talked about again it was just too much for them” - Jan Ruff O’ Herne, Victim. “When I escaped Gaotianpo, I brought a few things with me, including a Japanese lunchbox and some Japanese clothing. I didn’t keep them because they made me angry and upset when I looked at them. Now I only have this left. I thought it must be useful so I took it with me. But I didn’t know what it was.”Lei Gui Ying, Victim. “I was kept in the comfort stattion for about three months. In the seventh month of that year 1938, Mr Yang, a clerk who was working in the puppet town government, helped free me. People said that Mr Yang had an interest in me because of my good looks, so he paid ransome and used his connections to get me released. Mr Yang wanted me to be his concubine, but I refused. I told him I had a husband and I wanted to go home.” -- Zhou Fen Ying, Victim. “ When I was released my mother-in-law did not want me to return home. She could not take the widespread gossip in the village, where people were saying that I was defiled by the Japanese troops. However, my husband Jin Cheng accepted me. He said, “Fen Ying was kidnapped by the Japanese troops but this was not her fault.” He brought me home despite what the villag ers and mother-in-law said. Still he was deeply humiliated because they looked down on me. I could sense that his heart was filled with anger and hatred towards teh Japanese troops.”- Zhou Fen Ying, Victim. “I was finally freed in 1939 when the Japanese troops withdrew from Miaozhen. By that time I still suffer from constant headaches, renal disorder as well as incurable mental trauma. I am not able to free myself from mental stress, even though I never did anything of which I should feel ashamed.” - Zhu Qiao Mei, Victim.

“ I secretly talked to another Hubei girl whom the Japanese called ‘Rumiko’ and we planned to escape. However, we were caught as soon as we ran out. A Japanese soldier held my hair and violently hit my head against the wall. Blood immediately gushed out. The beating left with incurable headaches; I still suffer from them to this day.” - Yuan Zhu Ling, Victim. “A Japanese soldier hit the soft spot on my side with his gun when the troops abducted me. The internal injury it caused becasme increasingly painful, althought there is no scar on my skin. I still suffer from the sharp pain in my side today; it radiates through my lower back. At the time no doctor examined me, and they didnt giver me any medication either.” - Yuan Zhu Ling, Victim. “I was finally bailed out by Yao Ju Feng, head of the local Assocaition for Maintaining Order. He was the relative of my mother’s, so my parents begged hum to help me obtain my release.

Yao Ju Feng obtained the Japanese officer’s permission to let me return home briefly by telling htem that there was an emergency in the family and that he would send me back to the comfort station.”

- Tan Yuan Hua, Victim. “When I got back to my home village, my husband-to-be, Li Wuxiao wanted to cancel our marriage engage ment because I had been raped by the Japanese soldiers. A man called Li Ji Gui, who was also a resistant movement activist in the village and much older than I was willing to help me out. However, Li Wu Xiao asked him to pay for my release. With the help of the villag head, Li Ji Gui paid Li Wu Xiao dozens of silver dollars and took me home. Li Ji Hui married me and paid for the treatment of my injuries.”- Tan Yuan Hua, Victim. “That day I passed out again and didn’t wake up for quite a long time, so the Japanese soldiers thought I was dead and threw me into a runnel by the village. I had no clothes on my body and the water in the runnel was frozen. Luck ily, Zhang Meng Hai’s father discovered me and saved my life. He said that my body was already freezing cold and that I had almost ceased breathing when he saw me. He watched over me for a day and a night, feeding me soup and massaging my body.” - Huang You Liang, Victim.

These testimonies should only remain as words. Their experiences are immeasurable, unquantifiable, and should not be visually re-enacted.

Early Discussions and Apologies -

Discussions of the comfort women system started in the early 1990s, where there was rising international attention on unaddressed human-rights crimes. This began in May 1990, when the former South Korean President, Ro Tae Woo, formally requested the Japanese government to release the names of Korean civilians who worked as forced labourers during the war. (Naoko, 2016)

In the midst of these developments, this issue was brought to the table in one of the budget meetings held by the House of Councillors of the Japanese Diet in June 1990. In this meeting, Councillor Mootaka Shoji, demanded the Japanese government to conduct an investigation on the comfort woman system, and whether if it was part of the forced labour draft during the war. (Naoko, 2016)

The Japanese government denied these accusations and claimed that it was beyond their capacity to investigate this matter, as these women have been recruited by private entrepreneurs. (Naoko, 2016)

In response, one of the victims, Kim Hak Sun, made her case public in August 1991. Following her confession, many other victims have came forward with their stories. (Naoko, 2016)

However, this issue only came under scrutiny when Yoshimi Yoshiaki, a historian at Chuo University, discovered documentary evidence from the National Institute for Defense Studies Library. These documents identified the Imperial Japanese Army’s involvement, by providing details on the recruitment process, establishment, operation and hygienic inspection of comfort stations. (Yoshiaki,1995)

Upon publishing his findings on the front page of Asahi Shinbun in January 1992, the Japanese government ordered all agencies to review their archives. (Naoko, 2016)

On 4th August 1993, the Kono Statement was released. This statement acknowledged the army’s involvement and expressed “sincere apologies and remorse” on behalf of the Japanese government. Accompanying this statement, the Asian Woman’s Fund was formed where atonement money was distributed to the victims and their families. (Naoko, 2016)

However, these efforts of reparation have been highly contentious because many believed that the Japanese government failed to offer ‘moral’ compensations.

This was depicted through its censorship in Japanese history textbooks, the constant demand to remove the comfort women memorial statues, its insensitive appropriation in national art festivals, etc.

With this, this research will analyse the grammatical connotations of these ‘apologies’ to understand the government’s true intentions, before developing an architectural response.

Since 2011, comfort women memorial statues have been built in an effort to urge the Japanese government for a sincere apology. The first statue was erected in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul. Despite Japan’s demand for its removal in 2015 as a condition for its apology, Seoul has refused this request and has continuously argued that the apologies provided were insincere. Following this statue, many new identical and reappropriated statues have been erected across the world to pressure Japan for a ‘moral’ compensation.

Part 1 will focus on interrogating the honesty of these statues. Using the first statue in Seoul as a point of departure, Part 1 will begin by analysing its position, depiction and associated events. Subsequently, this research will discuss how these statues depict agonism, by documenting the consequences of erecting the statues in the Philippines. With this analysis, this research will explain how the statues were ineffective in addressing the victim’s wants, despite its successful depiction of agonism.

Activism Through ‘Memorials’

-

Since 2011, a series of comfort woman memorial statues have populated across South Korea, China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Australia, the US and Germany. Despite its modest depiction, these statues have been a source of geopolitical tension between its host countries and Japan. On all occasions, the Japanese government has persistently demanded the removal of these statues. To the public eye, these actions are questionable as they seek to remove acknowledgements of victimhood, which is in stark contrast to other controversial memorials that iconify perpetrators of colonialism. (Matsumoto, 2017)

Therefore, using the first erected statue in Seoul as a point of reference, the followings paragraphs will analyse the statue’s position, appearance and associated events.

Position as a Symbol of Protest

-

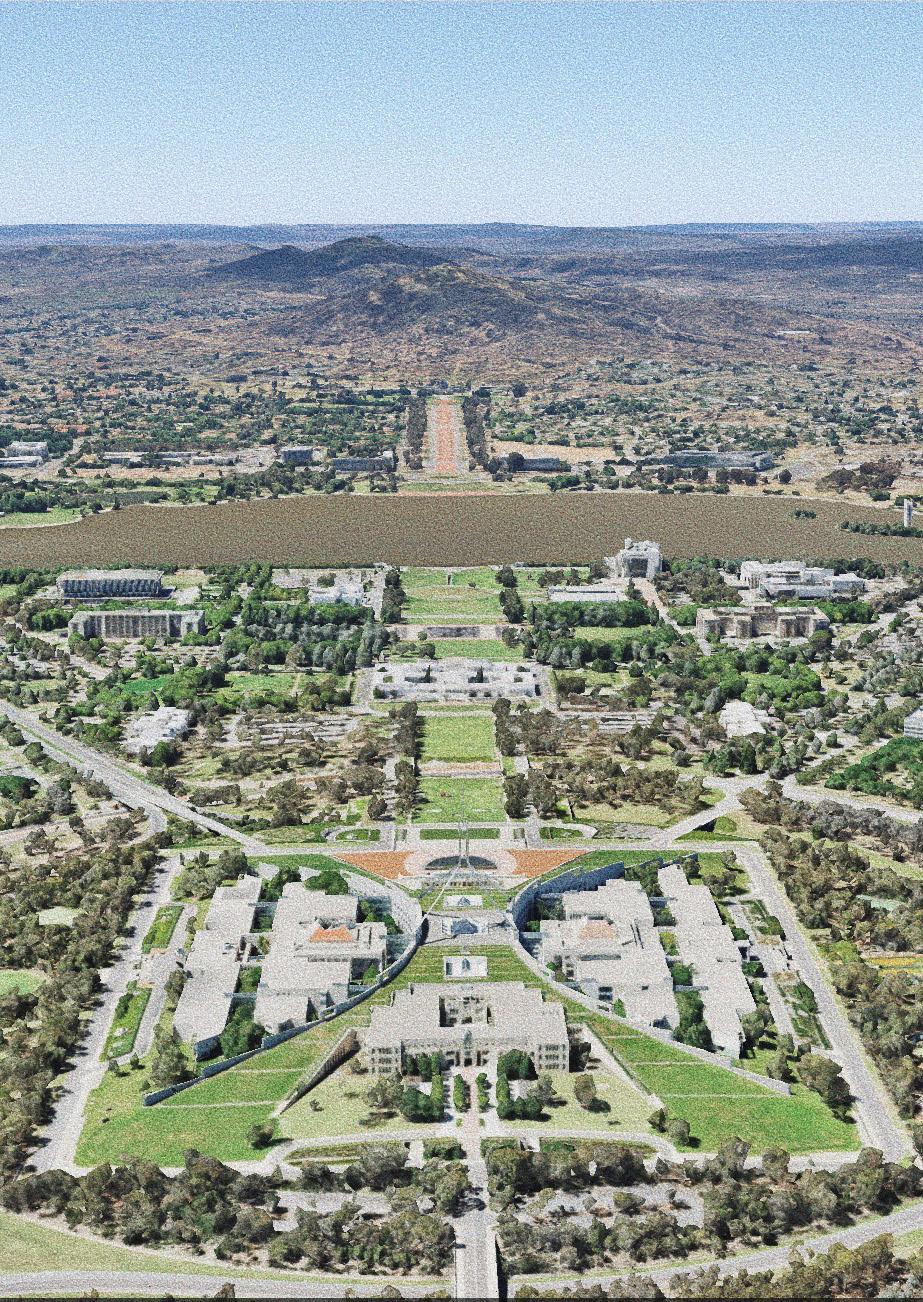

Designed by Kim Seo kyung and Kim Eun Sang, the first comfort women ‘memorial’ statue was erected in Seoul on 4th December 2011. This statue sits at the centre of the weekly Wednesday protests held by ‘The Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan’. (Kwon, 2019) The mere existence and rootedness of this statue serves as a permanent protest against the Japanese government’s handling of this issue. The statue is also positioned on the side walk of Yulgok-ro, a busy main road of in the government district. This not only affirms the gravity of the issue but also serves as a constant reminder for its need to be addressed. Lastly, it is oriented towards the Japanese embassy, which explicitly identifies its target audience - the Japanese government.

Appearance and Intended Symbolism Depiction

-

The memorial depicts a young girl dressed in chima jeogori, sitting beside an empty chair. This young girl represents the Korean victims of the comfort woman system and the empty chair seeks to affirm the unregistered victims and victims that have passed away without an apology. Her heels are raised and her fists stay clenched as she fixates her sight towards the Japanese Embassy. These details reflect the victim’s discomfort towards the event’s censorship and her resilience towards an earnest acknowledgement from the Japanese government. She is accompanied by a bird on her left shoulder, which not only expresses her hope for peace but also represents the presence of the deceased victims in this urge for acknowledgment. When light is cast upon this statue, a shadow taking the silhouette of an aged woman appears, which reflects the passing of time during the victim’s endured hardship. (Shim, 2021)

Seoul’s

Comfort Women ‘Memorial’ Statue as of 2011

T he statue acts as a cursor for apology through its presence, position and orientation.

Seoul’s Comfort Women ‘Memorial’ Statue as of 2015

T he statue reveals the true sentiments of the Japanese government through the associated events.

Seoul’s Comfort Women ‘Memorial’ Statue as of 2022

T he statue documents second-hand architectural traces as an indirect confession.

Associated events -

Upon its erection, the statue’s implicit connotations have been a source of geopolitical tension between Japan and South Korea. As such, the next few paragraphs will analyse the statue’s associated events and explain how they depict the Japanese government’s confession to the use of ‘forced coercion’.

In 2015, the Japanese and South Korean government reached a controversial agreement to resolve the ‘comfort women system’ issue irreversibly. This agreement involved a one-time 1 billion yen compensation through a foundation, in exchange for the statue’s removal.(Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2015) However, this agreement fell apart at the end of 2015.

After this agreement fell apart, the Japanese embassy received a ‘renovation’ permit for a new six story building. After its immediate demolition, construction was repeatedly delayed and has not commenced as of 2022. As such, the Seoul authorities have revoked this ‘renovation’ permit to align with the local law- construction must start within a year upon the issuing of the building permit. (The Straits Times, 2019).

Provoking acts of denial as confession

-

Despite the statue’s failed attempt in attaining an apology, the events following its erection indirectly affirms the Japanese government’s confession to the use of of ‘forced coercion’. This demand for the statue’s removal through ‘contractural’ means, followed by the immediate demolition of the embassy when the agreement fell apart, indicates the government’s denial to contend with the issue. Thus, through provoking formal acts of denial, the statue has been effective in asserting the event’s validity.

Second-hand Architectural Traces as Confession

-

Other than provoking acts of denial, the statue uses ‘second-hand traces’ to assert the event’s validity. In “Forensic Architecture is Looking at the Past to Transform the Future”, Eyal Weizman explains how architecture uses the ‘low-card principle’ as a form of documentation - by recording traces that are left behind by surface contact. (Weizman, 2022). Contextually, the vacancy of this plot of land (previously occupied by the Japanese embassy) documents this confession of ‘forced coercion’. Its occupancy is equivalent to ‘denying the event’s validity’, which deters local investors from developing on this plot. Thus, through indirectly imposing connotations, the statue has been effective in asserting the event’s validity.

Programmatic Implications Through its Material Rhetoric -

Despite its formal depiction, the comfort woman ‘memorial’ statue operates architecturally through its programmatic implications. The following paragraphs would explain how this statue functions as a cursor for apology, state-wide protection and public participation.

The statue acts as a cursor for apology through its presence, position, and orientation. Commissioned by the ‘Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan’, this statue sits on the footpath facing the entrance of the Embassy of Japan in Seoul. Its presence and site position serves as a strong prompt for the Japanese government to provide a formal and sincere apology. In addition, its confronting orientation serves to engage with the viewer’s line of sight. This is expressed by the Japanese ambassador’s recount during a public forum stating “Everyday I go to work at the embassy and I see the statue. I don’t think it was the right decision to put it there”.(Shim, 2021) Despite being unsuccessful in attaining an apology, this statue has been successful in arousing dissent and revisiting discussions on the comfort woman system. This is depicted in the 2015 controversial agreement between the Japanese and South Korean government. As mentioned earlier, this agreement involves a one-time 1 billion yen compensation through a foundation, in exchange for the removal of the statue. (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2015) Architecturally, this statue has brought the Japanese government’s attention towards an issue that was claimed to be ‘inappropriately’ resolved in the past. This is also depicted in the timely 2015 demolition of the Japanese Embassy. Through its demolition, the comfort woman statue no-longer faces the Japanese embassy, but an empty lot of land. As of 2022, this plot of land remains untouched with adhoc barricades and barb wires that claims to

be ‘a renovation in talks’. Though it no longerserves its confrontational purpose, this statue has been programmatically successful in revealing the sentiments of the Japanese government- denial and refusal to further contend with this issue.

The statue engages with the local government programmatically by inviting statewide protection. Other than receiving round-the clock surveillance by the police, this statue is heavily guarded by students and activists. (Ock, 2016) This could be seen from the wooden pallet, covered by a removal plastic sheet, that always sits to the side of the statue. This shelter evidences the constant presence of student activists on guard. Thus, despite its formal depiction, this statue spatially engages with the users through its urge for protection.

Lastly, the statue cursors the public to participate in its call for an apology. Unlike the empty chair in Poland’s Krakow Ghetto Hero Square, the empty chair in the Comfort Women Memorial Statue serves two purposes - to represent the presence of the deceased victims and to invite the public to take a seat. (Shim, 2021) In this context, the act of ‘taking a seat’ transforms a passive bystander into an active participant, which are strictly identified as the intentions of the commissioner, ‘Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan’.

Agonism -

In the midst of such vicarious activism, it is important to understand that an apology from the Japanese government will not resolve the ‘comfort women system’ issue.

An apology will not erase nor heal the wounds that have already been inflicted.

Instead, this apology is a plea for acknowledgement - a settlement that the victims hope for.

Unfortunately, in this case, this moral concession is rejected by its perpetrators. With this, any cursor as a form of activism is important, including these statues. As such, the following paragraphs will explain how these statues use the concept of agonism as an effective mode of indirect confession, despite not attaining an apology. These observations would be further substantiated by documenting the consequences of erecting the statue in the Philippines.

Coined by Chantal Mouffe in “The Democratic Paradox”, agonism is a social theory that uses conflict to bring awareness to an issue. (Mouffe, 2020) Through this mode of action, agonism asserts that ‘most conflicts are not fully resolvable’. It blatantly admits that most resolutions are built upon compromises, which in hindsight, do not follow the victim’s initial terms. As such, these concessions should not be seen as ‘solutions’ that resolve conflict. Thus, unlike pluralism, which introduces an opposition to achieve ‘amicable’ consensus, agonism introduces an opposition to maintain conflict. This tension between the protagonist and antagonist is retained as it acknowledges the irresolvability of conflict, and does not accept any form of compromise as a solution. Instead, agonism capitalises on this conflict so as to bring awareness to the protagonist, leaving the protagonist on the judging table for audiences to develop their own position rhetorically.

Agonism in the Context of the Statues -

Contextually, the comfort women ‘memorial’ statue capitalises on conflict to assert the event’s validity. For the statue in Seoul, the statue takes the role of the ‘opposition’ that amplifies the protagonist’s stance - the denial of forced coercion in comfort stations. This amplification is carried out through direct confrontation, where the statue provokes the Japanese government to demand for its removal and to dismantle the embassy. These acts of silencing and unwillingness to contend with the issue highlights the government’s denial, which is an indirect confession to ‘forced coercion in comfort stations’. As such, through attaining a response, these statues are effective in asserting the event’s validity and garnering an indirect confession from the Japanese government.

In the Philippines, the comfort women ‘memorial’ statue garners an indirect confession though its removal. With reference to the missing posters, this statue was stolen twice - the first from its original site in April 2018 and subsequently from the artist’s studio in August 2019 after it was ‘found’. (ABS CNN, 2018) Other than the publicised back and forth correspondence between the Japanese Minister for Internal Affairs and the Philippine’s Department of Foreign Affairs, these suspicious events were followed with news stating that “Philippine lawmaker received a tip that the the then ADB president, Takehiko Naoko had categorically told Duterte that dismantling the statue was a condition for a loan for the construction of a subway in Manila’. (Robbles, 2021) The urgent need for a complete archival erasure highlights the Japanese government’s discomfort with its existence, which indirectly confirms the event’s validity. In addition, the derogatory use of monetary intimidation to erase well-known history further affirms the government’s desperation, which further emphasises the event’s validity.

A Built Symbol with Varied Intepretations

-

Despite shedding light on the protagonist’s stance, these statues were ineffective in solely addressing the victim’s wishes. Coupled with media distortion, the statues’ lack of curation prompt stakeholders to develop their own interpretations. Though inevitable, this widened range of interpretation is concerning because it has ‘excused’ or ‘permitted’ the statues’ misuse. In this scenario, the victims’ trauma has been mocked, uncomfortably glorified, exploited and monetised. As such, the following paragraphs will dissect the perceptions held by different stakeholders.

To its victims , this statue validates the trauma they have suffered . This designated structure formalises the existence of the comfort woman system, which reaffirms the victim’s ordeal. Referencing Carole Blair’s analysis of memorials, translating acknowledgements into its material rhetoric is powerful as it allows validation to be ‘personally’ conveyed. (Blair,1999) By taking a ‘no text is text’ approach, this statue allows an acknowledgement to be received on the victim’s ‘own terms’ given its relatively more open-ended interpretation. This is as opposed to overarching verbal apologies which inevitably labels and limits the victim’s trauma to a set of a conditions, which may not be all-encompassing or as reflective. Thus, with material rhetorics taking an open-ended approach, it does not trivialise the complexities of trauma, nor misrepresent trauma as measurable and comparable.

To the Japanese government , this statue is a symbol of discord, embarrassment and a memory to erase Depicting any form of victimhood in a public structure would inevitably provoke pedestrians to identify the crime at hand. This would undermine the government’s past attempts at censorshipcomprehensive destruction of archival, built and human evidences, elimination from textbooks, propaganda, etc. Thus, as a response, the Japanese government has actively insisted on the statue’s removal. As such, these actions clearly indicate the government’s unpleasant interpretation and dissent towards this built structure.

To misinformed activists , this statue could serve as an opportunity to promote personal opinions or nationalistic ideals through the ‘monopolisation of pain’ (Park, 2011). Park defines the ‘monopolisation of pain’ as the act of basing assertions on what is ‘claimed’ to be the stated intentions of the victims. In the flux of emotions, there is a subconscious tendency to endorse opinions that coincide with our own. This causes the victims’

objectives to be misrepresented. As such, instead of the statues being an agency fo survivors, these statues could be misconstrued to serve nationalistic sentiments (innocent girls violated by foreign oppressors). Examples of this would be the statues in Melbourne and Sydney. Other than its questionable locations, these statues only depict Korean victims, and not its Australian victims. Although it serves the same cause and raises awareness, this inconsistency questions the honesty of activism.

Melbourne’s Comfort Women ‘Memorial’ Statue as of 2022

The statue’s location in Oakleigh, orientation towards a carpark and depiction of nonlocal victim (and not of its local victims) imply the statue’s unclear obejctives. (potentially nationalistic ideals?)

To activists with underlying intentions , this statue serves as an opportunity to profit gain . In May 2020, Lee Yong Soo, a victim, accused the ‘Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan’ for exploiting and monetising off the victims’ stories. She claimed that the council has embezzled donations that were used to support the remaining aged survivors, which subsequently led to the council’s apology for ‘banking errors’ (Mccurry, 2020). This case study sheds a different light on how this statue is regarded, ‘an opportunity’ for third party financial gains.

To governments of previously occupied territories, this statue served as a pawn for the political economy of diplomacy. This could be seen in the two case-studies that were highlighted previously. For the statue in Seoul, the Japanese and South Korean government reached a deal to remove the statue in exchange for a one-time 1 billion yen compensation. (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2015)

Despite not following through, this agreement was reached via a private phone call without consulting the surviving victims. (Asian Boss, 2018). For the statue in the Philippines, the Japanese Minster for Internal Affairs and the Filipino Department for Foreign Affairs reached a deal to remove the statue in exchange for a loan for the construction of a subway in Manila. (Robbles, 2021) This too was done without the victims’ knowledge. Through these acts, the victims are detached form their trauma.

Instead, their trauma is politicised and used as a currency between countries.

A New Currency as an Act of Defiance

The new currency returns the victims their lost power over their stories.

As previously highlighted, the statues’ vagueness has caused victim stories to be misused. These new opportunities to misconstrue is concerning. It not only dismisses the progress made, but also trivialises the victims’ courage to come forth with their difficult stories.

Part 2 will focus on interpreting the victims’ underlying wishes. Using a bottom-up approach, part 2 will dissect the structure and the choice of words in the widely disseminated ‘Victim’s 7 demands’. These findings will be compared to the sentiments voiced in publicly available first-hand interviews to determine its consistency. Lastly, this research will explain the selected mode of action, as a response to the ineffectiveness of the current statues.

Dissecting the ‘Victim’s 7 Demands’ -

Announced by Comfort Women Action for Redress Education (CARE), the ‘Victimd’ 7 Demands’ refer to the victims’ 7 wishes for justice to be achieved. This list not only formalises their intentions, but also provides an indication of how much progress was made.

Upon dissecting these 7 demands, it was clear that this document was repetitive, which could come across as disorganised or intentionally ‘overblown’. For instance, ‘(1) Admission of Guilt’ is a repetition of ‘(3) apology’ and a preamble for (2) and (4) - (7).

Should this be unintentional, this repetition conveys a lack of clarity in objectives, which reduces this document’s creditability. This is concerning because the victims’ position is misrepresented by the very organization that represents them. In this scenario, if the very organization that represents them is unable to provide a clear depiction of their sentiments, who will, or more of who can?

On the other hand, should this be intentional, must these demands be overblown to solely grasp the public’s attention? To get a better idea of the victims’ sentiments, a range of documentaries, selected publicly available first-hand interviews, UN panels, and research articles were scrutinised. Subsequently, screenshots of their words and facial expressions were placed in adjacency with the ‘7 demands’. This exercise was critical as it highlights the inconsistencies between the victim interviews and the ‘Victims’ 7 Demands’ released by the activist group. An example of this inconsistency is (7) Commemoration: Erect memorial monuments and build archives. Though Grandma Kim supported the comfort women ‘memorial’ statue by conveying her unhappiness when the administration aimed to take it down, it was implied (from the rest of the interview) that she saw the statue as a cursor of activism, and not a patronage to its victims. This is in contrast to the ‘Victims’ 7 demands’ definition of a memorial monumenta physical object that commemorates and iconifies the services made by individuals. This sentiment is also reiterated in Grandma Lee’s denial and disgust to be called a ‘comfort woman’. From this, it is critical to emphasise that this event should not be defined as ‘a service to the country’, much less iconified as a monument. In addition, the idea of having a designated archive does not align entirely with the victim’s wishes. From Grandma Mardiyem’s fear of being photographed, Grandma Lin’s discomfort in retelling the story and Grandma Adela’s refusal to tell her children, it is clear that many victims are uncomfortable with sharing their stories, much less have them put on a inherent judging platform for the public. As such, a sensitive balance between exposing detailed recounts whilst providing documentation of its existence must be carefully considered.

Textbooks as a Medium -

Among the 7 demands, ‘(6) Education: Record the sexual slavery system in history textbooks’ best reflects the victims’ wishes. As such, this thesis will focus on (6) as the main mode of action. The next few paragraphs will explain why this mode of action is most appropriate and elaborate on the current controversy.

Admitting a flawed system in a textbook is an implied form of apology, that is appropriate given the delicacy of the issue. The textbook serves as an appropriate medium due to its connotations, accessibility and premise of text.

In terms of connotations, the textbook is understood as an authorised text that represents national history. (Hiroshi, 2012) As such, the government’s act of not censoring, and explicitly recording it in this document, formalises the event’s position in history. In addition, the Japanese education system relies heavily on textbooks to moderate the scope of teaching across all schools. Thus, the act of actively explaining a committed crime to the country’s future generation is depiction of reflection and guilt. In terms of accessibility, the textbook is a more inclusive medium as opposed to memorial monuments. The simple and direct language is catered primarily for the younger audience, though still easily comprehendible by the wider public. This ease of dissemination conveys the government’s proactiveness in confessing a committed crime. Lastly, in terms of premises, the textbook is formerly known to contain factual information, devoid from emotions. As such, this event will not be asserted and explained through detailed personal recounts, which is appropriate given the sentiments conveyed by victims in previous analysis. As such, given the specific nature of textbooks, (6) will be the most appropriate mode of action.

As of current, history textbooks are not written by the Japanese Ministry of Education (MEXT). This has been a long-standing order by the the Supreme Commander Allied Powers to democratise education and to prevent the white washing of events. However, MEXT controls the ‘Textbook Authorisation System’ which screens the textbooks submitted by private publishers. This controversial system has disincentivized publishers from mentioning the ‘coercive-nature’ of the comfort women system, which paints the event in a different light. Currently, Yamakawa’s high school history textbook is the only one that mentions the ‘coercive nature’ of the comfort women system, which appears as a footnote. This tight control over its coverage has been effective given that many students are unaware of this event as depicted in Tiffany Hsiung’s documentary, The Apology.

- PART 3 -

As depicted by the statues, agonism has been an effective approach in garnering an indirect confession by the Japanese government. However, it has failed to solely address the victim’s wishes due to its vague delivery (explained in Part 1) and distorted objectives perpetuated by activist groups (realised in Part 2).

Part 3 will focus on generating an architectural brief. It will begin by deconstructing the concept of agonism into its three themes, setting the premise for intervention. Subsequently, part 3 will explore architectural precedents according to the three themes that was previously derived. Lastly, it will conclude with an architectural brief that responds to the failures of the statues.

Deconstructing Agonism -

As discussed previously, agonism is a social theory that uses conflict to bring awareness to an issue. It does so by introducing an opposition, not to achieve consensus, but to shed light on the protagonist.

Through this definition, agonism is built upon 3 main themes - the presence of an opposition, the use of aggression to direct attention to the protagonist and the irresolvability of conflict. These themes were depicted by the statue to a certain degree.

For instance, the introduction of the statue in response to the Japanese government’s denial is a form of opposition. Subsequently, the pairing of its uncanny site position and its peacefully-assertive disposition depicts aggression. Lastly, its proliferation around the globe, despite the Japanese government’s dismay, conveys its ambition to maintain conflict. This is under the knowledge that this problem will never be resolved, even if an apology was issued.

Despite addressing these aims, the statues were only aggressive in delivery, but not in its objectives. This lack of clarity has opened more room for interpretation, which has encouraged the statues’ misuse. As such, this architectural response will readdress the theme ‘aggression’ by clarifying its intentions, in an effort to narrow this range of interpretation. This involves using design decisions to rigorously specify the target audience, spatial program and intended outcomes. This process of specifying will be carried out by further deconstructing the theme ‘aggression’ into three main areas of focus - visual traces, methodology and programmatic implications

However, before developing a response, the next few essays will explore architectural precedents that sensitively practice the themes of the above framework.

Presence of an Opposition Acknowledging Presence through Participation

-

But how could we ‘sensitively’ participate when the memory does not belong to us?

In “Difference and Repetition”, Deleuze suggests “count upon the contingency of an encounter with that which forces thought to raise up […]. Something in the world forces one to think. This something is an object not of recognition but of fundamental encounter” (Deleuze, 1994). Here, Deleuze describes how ‘staged’ encounters inherently provoke thought. Spatially, ‘staged’ encounters could be inferred as deliberate design decisions. These decisions takes the form of an ‘existence’, whether it be a presence or a strong absence of a material object in space. This mere existence provokes thought, which in itself, is a form of participation, whether it be conscious or subconscious. However, in the delicate context of trauma, this scope of participation should be narrowly limited. As such, how should architecture be curated to ensure that ‘participation’ is carried out both sensitively and morally?

In “ Uncertain Architecture: Transforming Normativity through the National Memorial for Peace and Justice ”, Frayne points out a common misconception of ‘history’ - a collective narrative that represents society. (Frayne, 2021) Instead, he argues that historical discourse should be perceptual as only certain events are registered. This affirms that there are ‘experiential’ gaps in historical archives and that architecture has the social responsibility to reflect this. As staged encounters has the power to provoke thought, design decisions has the power to distort. With these uncertainties, architecture should not aim to ‘reconstruct’ the past. Instead it should solely affirm the presence of registered events to provoke thought.

The next two paragraphs will discuss the two different modes of participations and its implications.

Provocation through Physical Bodily Movement -