40 minute read

US West Coast Ports see

US WEST COAST PORTS SEE VOLUMES HIT

A summary of the results being reported by ports in the US for 2019 is showing there was a divide by coast, with the West Coast seeing a decline compared to 2018 due to concerns over the US-China trade war, while the East and Gulf Coast facilities generated improvements due to lower exposure to trade with China. In more detail, the San Pedro complex saw a decrease for 2019 for both Los Angeles (-1.3%) and Long Beach (-5.7%). Looking at the specific numbers, f or 2019 Los Angeles recorded a total of 9.34 million TEU, which compared to 9.46 million TEU for 2018 and stopped the port surpassing the 10 million TEU barrier for the first time.

The other port in California, Oakland, provided a similar story, with a fall of -1.8% in handling 2.5 million TEU in 2019 and 2.55 million TEU one year earlier in 2018.

In comparison, Long Beach feel back below of the 8 million TEU level in 2019, with the 7.63 million TEU recorded down on the 2018 figure of 8.09 million TEU.

A similar position occurred in the US Pacific Northwest, with the Seattle-Tacoma ports handling 3.78 million TEU for 2019, down on the 3.8 million TEU for 2018 and reflecting a decline

of 0.6%, so smaller than generated further south on the western seaboard.

For the major container ports not on the West Coast the position in 2019 was more positive, with gains recorded. New York/New Jersey remains the largest container volume ports on the US East Coast and its 2019 total of 7.47 million TEU was a 4.1% rise on the 7.18 million TEU handled in 2018.

Likewise, Savannah increased its throughput to 4.6% in 2019 compared to 4.35 million TEU in 2018 (+5.7%), while Norfolk saw a

8 US West Coast ports were impacted by trade war concerns in 2019

rise from 2.86 million TEU to 2.94 million TEU (+2.9%) and Charleston enjoyed growth of 5.2%, from 2.31 million TEU to 2.44 million TEU in this same two-year period. Growth was even more impressive for Houston on the Gulf Coast, which saw its 2018 total of 2.7 million TEU improve to 2.99 million TEU for 2019, up by 10.6%, and the port will expect to surpass the 3 million TEU level for the first time in 2020.

Terminal de Contêineres de Paranaguá (TCP) has posted record throughput figures for 2019, of 915,242 TEU, following a commercial drive to attract more shippers from the neighbouring states of Sao Paulo and Santa Catarina.

The increase of 12.5% over the 2018 figure of 800,000 TEU owes much also to the closure of Libra Terminais in Santos – Brazil’s biggest and busiest port for containers, located some 151 nautical miles away – as this greatly assisted TCP in picking up more transhipment cargoes. Juarez Moraes e Silva, the Institutional Director of TCP, said that a strong commercial push into neighbouring states has harvested rich dividends. “Some parts of Santa Catarina and Sao Paulo are closer to Paranaguá than they are to the ports of those states but we are also winning shippers from greater distances, especially in Sao Paulo, because of the congestion and delays at Santos,” said Silva. “Also, as well as strong commercial work, TCP offers the option of the railroad, which directly accesses the primary area of the Port of Paranaguá, reducing logistical steps and, consequently, making the operation more competitive through Paranaguá.” This argument is sound, given that around 15%-20% of containerised cargo through TCP is carried by rail, much higher than the 2%-4% through Santos.

Moraes e Silva stated that the release of the new docking berth, which took place last November, also influenced the result of 2019. “Our terminal increased its handling capacity by 60% and is now able to simultaneously operate three of the largest and most modern ships of c ontainers,” he explains. Silva added that the sectors with the most growth were reefer (+14% over 2018), pulp and paper (+31%), and automotive (+6%).

Paranagua is currently the “Chicken Export Capital of the World” and last year exported more than 110,000 TEU of chicken. For 2020, the forecast is for growth to be above 10%, mainly due to the movement of commodities such as wood, cotton, paper and cellulose, refrigerated cargo and consumer goods and electronics. TCP POSTS RECORD 2019 AFTER SUCCESSFUL DRIVE

BRIEFS

Box traffic up in Panama The Panama Maritime Authority confirms its domestic ports handled a combined 7.31 million TEU in 2019, against around 7 million TEU in 2018. Noriel Araúz, Minister for Maritime Affairs said, “Our expectations for 2020 are positive, because since the beginning of this administration, we have strengthened ties with important countries that have experience in ports to establish collaboration for the development and implementation of initiatives aimed at boosting the maritime sector.”

Maersk MedMontreal change Maersk Line is adding a call at the new APM Terminals’ Vado Ligure terminal to its Med Montreal Express (MMX) service. This facility has recently been inaugurated by APM Terminals and now fellow AP Moller company Maersk Line has added a call after Marseille-Fos and Algeciras. Deployment will be five vessels in the 2,200TEU-2,500 TEU range, with the service change in place during early March.

Traction for “Enfidha?” A new deep-water part at Enfidha in Tunisia may, finally, be seeing some traction. A company has been established in the North African country, with the possibility of initial works starting in 2020, with the aim of phase I operations starting in 2023 or 2024. Longer-term, container capacity of up to 1.6 million TEU by 2026 is being mooted. The publicprivate partnership is expected to consider 60% finding from the state and 40% from private interests.

Increase your profits with intelligent solutions

Your challenge may be to invest in a cement handling solution that ensures profitable and sustainable growth for your business. Our expertise is to provide just that solution. Thanks to totally-enclosed conveyors, the operation with Siwertell equipment is free from dust and spillage.

• Ship unloading • Ship loading • Conveying

• Stacking & Reclaming • Truck unloading • Chipping • Milling • Screening • Wood residue processing

NY/NJ LEADS THE WAY AS US NORTH ATLANTIC UP

New York/New Jersey remains the largest volume port by some considerable margin in the US North Atlantic region and in 2019 its container terminals handled over 7.49 million TEU, up by 4.3% from the 7.18 million TEU for 2018. By comparison, Virginia saw its 2018 total rise from just under 2.86 million TEU to 2.94 million TEU for 2019, an increase of 2.9%, with Baltimore generating a small increase, from 1.02 million TEU to 1.07 million TEU for 2018 into 2019.

The other two regional facilities also enjoyed growth. Based on Philadelphia Port Authority estimates, a 2019 total of around 616,000 TEU represented an improvement of 5.5% on the 584,000 confirmed for 2018, while Boston maintained its current level of around 300,000 TEU with a minor rise from 298,000 TEU in 2018 to 301,000 TEU for 2019.

Based on the growth figures for 2019 over 2018, its clear that the US North Atlantic port region did not suffer any fall-out from Asia-US trade-related issues in the same way that the US West Coast ports did.

Over the longer-period since 2000 New York/New Jersey is generating annual growth of 4.8%, despite already being a highervolume port in the market.

Likewise, Virginia has increased its volumes by an average of 4.2% per annum between 2000 and 2019, while the highest growth (although not the largest volumes) is occurring at Philadelphia – endorsing the port authority’s ability to

8 NY/NJ saw growth of 4.3% in 2019, as US North Atlantic ports all saw increasing container volumes

continue to specialise in North-South and reefer cargo trades and supporting the foodstuffs industries. Baltimore’s growth over the same period was 4.2% per annum and the port will hope to see this figure improve once it finally

ge ts double-stack access through the Howard St. Tunnel in place (following recent confirmation that is has the necessary funding secured). So far, the impact of the US-China trade issues does not appear to have impacted container traffic in 2019, although the full extent of the impact of the current coronavirus issue is yet to be understood and could potentially generate some decline in cargo moving out of China.

IS FUTURE OF SANTOS OFFSHORE?

The future of Brazil’s biggest container port, Santos, could be offshore, according to a new study from the Santos Cecilia University (Unisanta) although it could be sometime after 2050.

Professor Adilson Gonçalves, head of the Advanced Nucleus of the Association for Collaboration between Ports and Cities (Rete) of the university and the Nucleus for Port, Maritime and T erritorial Studies (Nepomt) co-ordinated the studies of four Santos students who concluded that the best solution to the inevitable congestion that will engulf Santos as the port grows, will be an “offshore terminal” 2 km from the coast.

The plan allows for five berths with 20 meters draft with a fleet of trucks shuttling unloaded boxes back to the land storage areas, a port operation similar to that of Porto Itapoa, in Santa Catarina state.

Engineers and technical managers at Codesp – the port authority for Santos – have been looking at an area near Peruibe, some 30 km west of the Santos port area, for some years with a view to building an extension to the official port area.

This news comes as a new study from ANTAQ, the Brazilian National Agency for Waterborne transport, has highlighted the wide diversity in Terminal Handling Charges (THCs) made by terminals in Brazil’s key ports. At Santos the THCs ranged between $164 and $212 per TEU, depending on the terminal and the carrier, while most expensive was Suape, where Tecon Suape and charges between $283 and $315 per TEU. Cheapest terminals were in the Porto Itapoa (majority owned by Hamburg Sud/Maersk) and Sao Francisco do Sul port complex where prices ranged from $135 to $180 per TEU.

ANTAQ also registered that Pecem, a growing port for boxes on the north Brazilian coast, was charging between $155 and $195 per containers and Tecon Rio Grande, (owned and operated by Wilsons, Sons group) was the second most expensive, charging a THC of between $199 and $236 per TEU. ANTAQ stipulated that the figures were only provisional so far but the final figures, covering 85% of all Brazil’s containerised cargo movement, would be released before mid-2020.

BRIEFS

Backing for Melbourne rail The Victorian Government’s backing of the $125 million Port Rail Transformation Project developed by the Port of Melbourne has been welcomed by the Australian Logistics Council (ALC) as recognition of industry’s efforts to improve the efficiency of supply chains. The ALC says development of a new on-dock rail terminal at Swanson Dock East will help road congestion.

Pass on costs advice Transport operators have been advised to pass on higher costs to freight movers, as a result of stevedores increasing infrastructure charges. The Container Transport Alliance Australia has recently stated that “transport operators face a significant and rising burden to carry thecost of paying stevedore fees (or have their terminal access denied) ahead of collecting the amounts from import and export customers.

MSC Back at Valparaíso MSC’s North Europe to South West Coast South America service (via US East Coast and Panama Canal) has returned to Terminal Pacifico Sur (TPS) in Valparaíso. Since February the service is calling twice a week. It began in mid-2016, as a merger of two MSC services but stopped calling at Valparaíso in mid-2018. In November last year, MSC reinstated the northbound service.

Service back at Itaqui Aliança Navegação e Logística, the Brazilian cabotage and coastal shipping outfit, has re-instated a regular service calling at Itaqui, in the north Brazilian state of Maranhão. The Maersk/ Hamburg Sud owned shipping line is providing a weekly service to/from nearby traditional town/port of Sao Luis - to Manaus (in the Amazonas jungle region) to the north and west and to Santos and Sao Paulo in the southeast of Brazil.

In the shadow of the tariff wars the coronavirus has the potential to wreak further harm to global trade. W e are seeing the impact on exports from China as carriers begin to cancel sailings and potentially light loading in Chinese ports due to lack of stevedores and certain key products. US, Korean, Japanese and European motor manufacturers are reporting the beginning of parts shortages since they have run down inventories. Fortunately – unless you are in the automobile industry – the shortages come as demand for new vehicles has also dropped. The fear of the unknown is infecting human behavior. As it spreads, the virus will also impact the manufacturing industry, putting further downward pressure on global trade. It may be that fear will be the root cause of a global decline in trade growth. In theory Chinese factories were due to open on February 10th, 2020. In practice the

THE IMPACT OF THE CORONAVIRUS ON GLOBAL TRADE

Government has told workers they can work from home to do so and those in the manufacturing sector appear to be voting with their feet and staying at home. It is unlikely that industrial production ramps up before the beginning of March and that is probably an optimistic view.

Hardest hit is the motor industry and some hi-tech

8 Coronavirus has potential to wreak further harm to global trade

companies such as Apple. The biggest problem is the damage being done to the logistics supply chain. With Hubei province on lock down and quarantined, supplies for production ae not coming in nor are the factories functioning.

It goes beyond this as other manufacturing ar eas are on self-imposed lockdown and workers unwilling to come out into public environments. The loss of exports and the difficulty in importing commodities and raw materials needed by industry is damaging the Chinese economy as well as those in Southeast Asia that are so dependent on trade with China. GDP (gross domestic production) projections are spiraling down. Hong Kong, Singapore and Korea and economists are concerned that the disruption in the supply chain will impact most of Europe as well. The slight up-tick that we have seen in the Purchasing Manager’s Index globally is under threat. Given the depressed state of the main European economies, it would not take much to generate a short, sharp recession resulting from the decline in trade.

MIKE MUNDY THESTRATEGIST

If ever there is a strategy needed, it is a well thought out one to minimise the impact of the coronavirus. The big question is, of course, when will it be brought under control, or even better stamped out? There is clearly a lot of effort going into this but as of the time of writing this question the answer remains very much open to speculation. Work progresses on developing effective drugs to use against the virus. Two HIV drugs are being tested as a potential treatment – they target a protein that helps coronaviruses replicate. Scientists have also identified other existing medications that target this function plus there are a number of international research groups that are working on a vaccine. Three examples are: Inovio, USA which is employing a relatively new DNA technology to

CORONAVIRUS: MAKING IT GO AWAY!

arrive at a vaccine; the University of Queensland is assessing a “molecular clamp” vaccine and Moderna Inc. of Massachusetts is working with the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to accelerate its efforts in identifying a vaccine.

In comparison to the last time the world saw the outbreak of a similar virus in 2003 – severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) - China has been much quicker to tell the world what is occurring. When SARS appeared, by the time work on a vaccine gathered momentum the outbreak was nearly over. This time round work on a vaccine has got off to a timely start and at least offers hope if not certainty. The simple fact remains, however, that for the time being at least the emphasis pr esently remains on containment. And it clear that as of mid-February global supply chains are being progressively disrupted with increasingly worrying consequences.

One of the most influential factors here is China’s prominent status as ‘manufacturer to the world’ – much more so than it was in 2003 which, in turn, has spawned global and more complex supply chains. One indicator – Apple Inc. works with suppliers in 43 countries, all of them r ecipients of components from Apple’s manufacturers in China. Samsung, the world’s biggest smartphone maker while producing the larger proportion of its phones in Vietnam is highly dependent on China as a source of components. The border between China and Vietnam has been subject to closures due to fears over the coronavirus and so the truck transport of components is largely off the agenda, leaving the more expensive option of air transport as the alt ernative. But not everyone will be able to access air cargo capacity – leading to forecasts of increasing supply problems.

SHIPPING AND PORT IMPACT The problems for shipping and ports are well documented – freight rates dipping despite an increasing number of blank (void) sailings and reduced cargo volumes at China’s export ports in turn lowering the prospects at major US, European and other import gateways.

Respected industry analyst Alphaliner forecasts container traffic at Chinese ports, including Hong Kong, is likely to reduce by over six million TEU in the first quarter of 2020 and f orecasts global container throughput would fall by at least 0.7% in 2020.

Every February, the local and Norwegian and Greek Chambers of Commerce host an excellent conference along the East River waterfront (across from the long-gone industrial terminals in L ong Island City and Greenpoint). Most of the attendees represent shipowners, and la wyers and banker types who work closely with equipment owners and operators.

Themes vary from year to year, with IMO2020 having come and gone, and the U.S. elections looming closer, one of the big topics this year was economic sanctions. Another topic was decarbonisation, with greenhouse gasses now on the agendas of international maritime regulators more than ever before. On the sanctions part, one observation that struck me was that “shipping” is now in the crosshairs of the U.S. Department of State. An observation from the regulatory session (which also applied to the discussion of decarbonisation) is that

IT’S IMPORTANT TO BE PART OF THE MIX

“shipping” really refers to entire supply chains. Cargo origins, and links t o entities involved in their movement, are central to the State’s mission of punishing bad actors.

While we can save the politics for another article (or a chat with readers, many of whom know how to find me), suffice it to say that ports are now on a new regulatory radar screen, at least peripherally at this point.

The conference discussions on decarbonisation, a longer-term target for the maritime business

8 Those running the waterfront must be involved in conference agendas

(with the IMO looking 30 years out) also pointed to supply chains much broader than vessels only. Ports have already taken great initiatives towards greener operations. I daresay the port efforts have been more effective and impactful than those from many on the vessel side. The message that was imparted during the sessions, which should be passed along to the port community, is the level of interconnection and in tertwining in the cargo supply chains.

At the early Feb event, and at many others, we hear about silos, where one group in an organisation does not talk to another. Taken over a broader context, the message is clear that as data connectivity enables better networking, the ports will need to be part of the mix. Topics such as measuring emissions fr om individual vessels, at various points in their voyages, and then reporting them to commercial interests, and to regulators, were the among the items discussed. This is all coming, and the ports will need to be an integral part of such architecture. The US Coast Guard, with whom responsibility rests for Port State control of maritime matters, was certainly in attendance at the event- but attendees did not include folks running the working waterfront. Next year, if these subjects are again on the agenda, maybe they should attend.

PETER DE LANGEN THEANALYST

The move of DP World’s parent company (Port and Free Zone World) to purchase shares traded on Nasdaq Dubai and delist the company is highly interesting. If, as expected, the offer is accepted, DP World will be 100% owned by Port and Free Zone World, a subsidiary of the state entity Dubai World. In an announcement DP World stated, ‘Returning to private ownership will free DP World from the demands of the public market for short term returns which are incompatible with this industry’. If this argument applies for DP World, does it also apply to o ther port operators? Is it correct that a listing on a stock market goes hand-in-hand with a focus on short term returns? Is it correct that DP World will

THE OWNERSHIP OF PORT OPERATORS

r eturn to ‘private ownership’, when in fact it will essentially return to state ownership?

These are interesting and complicated questions. The numerous tales of companies that were purchased by venture capitalists (i.e. private ownership instead of a listing on the stock market) and restructured for short term gain cast doubt over the benefits of private ownership per se. In my view the more relevant distinction is between state-ownership and private o wnership. With a single, state-owned parent, pursuing a long-term strategy indeed easier than with shareholders aiming for financial return.

It is noteworthy that various of DP World’s competitors are also partly or fully state-owned (these include PSA, CS Ports and the other Chinese port operators, as well as the Hamburg based operator HHLA). Both for PSA and DP World, the case for state ownership historically makes sense - the economies of Singapore and Dubai are based on their status as hubs. Thus, the need for a world class port operator committed to providing world class terminal operations in Singapore and Dubai may justify state-ownership.

It is tempting to read this announcement as a signal that due to vertical integration (driven by digitalisation) the ‘public interest’ argument for Dubai is no longer about being world class in Dubai (that goal has been achieved) but about shaping and developing a global network, as

phrased in the DP World announcement: ‘a globespanning network of ports, economic zones, industrial parks, feeders, and inland transportation’, in which Dubai plays a central role.

In the case of DP World, one could argue that the track record so far justifies a ‘naïve’ view in ‘host countries’ (such as The Netherlands, Romania and India) that DP World acts the same as fully private international port operators (such as HPW, APMT). However, this perspective also suggests some host countries (India and Azerbaijan come to mind) may need to think carefully about securing their position in global logistics networks that are shaped to a significant extent by foreign state-owned enterprises.

My first encounter with ammonia was in the lab at school in Stroud. Mr Heymans tested our patience explaining that this simple compound of hydrogen and nitrogen was colourless. Of course, the odour was its giveaway, but ammonia was of zero interest to these greasy teenagers as it didn’t burst into flames or make a marshmallow cloud. Yet, we learned of its essential role as a feedstock and fertiliser on farms.

My next ammonia date was equally as unglamorous – an audit of a urea production facility in Bahrain. At least that enhanced my understanding of its synthesis into pharmaceutical products and as a base for textiles, refrigerants and even explosives. Its widespread use means it’s shipped in bulk and passes through – and is stored/chilled in – the global network of ports but you, literally, never see it. So, some of the infrastructure is there already.

These days, you won’t turn the pages of a maritime magazine without seeing the clamour for ammonia as an alternative fuel for ships. The chemical can be burned in engines to power vessels. That process does not generate CO2 emissions, which is a distinct advantage over traditional marine fuel.

Soon, the IMO is going to need to rethink its target year for ne t zero emissions. Countries such as the UK have recently announced that 2050 is the deadline for net zero in other sectors, now including airports and aviation. The pressure is on the IMO to improve the vision of a 50% cut in GHG emissions (against 2008 base year) for the total fleet (existing, and expected increase in shipping) by midcentury. The targeted reduction in total CO2 emissions for the total existing fleet is 40% by 2030 and 70% by 2050.

Engine designers are up for the challenge. Two-stroke ammoniapowered engines will be ready within four years. Like LNG, the first ships using ammonia as a fuel will be those tankers already transporting the product across

AMMONIA IS NOT SHIPPING’S PANACEA

. . . ammonia might not be the panacea for shipping’s contribution to global warming . . .

oceans. That will require extra space that will reduce the capacity for tradeable cargo.

There are a lot of other hoops to navigate through. As is the case with some forms of hydrogen, the ‘manufacture’ of ammonia gives rise to carbon emissions. Even now, its creation represents 2% of all global GHG emissions – that’s huge and right up there with cement and steel. The key to clean fuel is enabling carbon capture and storage (CCS), safely, and at an acceptable price. That’s a nut that hasn’t been cracked yet, not least with public acceptance. The use of green energy in production would make ‘zero carbon’ ammonia but that’s another hurdle to scale-up renewable energy to meet industrial needs. There are a few reasons other

reasons why ammonia might not be the panacea for shipping’s contribution to global warming. In the US, ammonia is classified as an extremely hazardous substance thanks to its causticity in concentrated form. Without subsidy , it’s cost would prove a deterrent while its efficiency – alongside stablemates vying for future market share, such as LPG and methanol – lags behind diesel’s performance and reliability. Burning ammonia also creates nitrogen oxides – a GHG emission – so we’re back to scrubbing to contend with that menace.

The University of Cambridge’s ‘Absolute Zero’ Report is reticent about the take-up speed of ammonia in ocean-going vessels while decarbonising simultaneously. The Royal Society is more upbeat, stating that ammonia is the only zero-carbon fuel that will propel a vessel across deep-sea shipping legs. Furthermore, it points out that ammonia is the only zero carbon fuel made from renewables that can be stored for months or even years.

8 IMO will need to rethink its target year for net zero emissions

Some are supporting the push into NH3 and creating port-hubs as they do it. H2U is developing a $118M facility integrating 30MW in water electrolysis and distributed ammonia production, near Port Lincoln in South Australia. The plant will use 100% wind and solar generation to produce up to 18,000tpa of green ammonia for agriculture and industrial use. This is a globally significant demonstrator project being one of the first commercial plants to produce carbon-free green ammonia (and hydrogen) from intermittent renewables resources. The potential for ammonia for large-scale power stations make it an attractive export opportunity, hence the development of a multi-user, multi-commodity deep-water port at the 1,100ha site.

We will certainly see more of these opportunities for ports to diversity and grow. I really should have paid a lot more attention in chemistry class.

unlocking value in the maritime & transport industry

www.mtbs.nl

Strategy port sector reform business strategy development masterplan public-private partnerships institutional & regulatory analysis

Valuation financial modelling & analysis feasibility study business case analysis economic cost benefit analysis risk analysis

Financing financial structuring project finance private placements finance procurement commercial & financial due diligence

Transactions transaction process strategy tender document & contract bid valuation & negotiation bid strategy & preparation training & courses

100 YEARS

2020

BOOK NOW AND SAVE 20% *USE CODE ‘EARLY’ Join us for The Motorship Propulsion & Future Fuels Conference 2020, incorporating centenary celebrations for The Motorship Magazine. BOOK NOW AND SAVE 20% *USE CODE ‘EARLY’ Join us for The Motorship Propulsion & Future Fuels Conference 2020, incorporating centenary celebrations for The Motorship Magazine. BOOK NOW AND SAVE 20% *USE CODE ‘EARLY’ Join us for The Motorship Propulsion & Future Fuels Conference 2020, incorporating centenary celebrations for The Motorship Magazine.

SAVE €411 for a limited time *Full price €2055

Delegate place includes:

• Conference attendance on both days - choice of propulsion or fuels stream

• Full documentation in print and electronic format • Lunch and refreshments on both days • Place at the conference dinner • Place on the technical visit

Sponsored by: Sponsored by:

Propulsion stream | Alternative fuels stream | Technical visit For more information on attending, sponsoring or speaking contact the events team: visit: propulsionconference.com contact: +44 1329 825335 or email: conferences@propulsionconference.com #MotorshipPFF

Sponsored by:

Supported by:

SILVER SPONSOR SILVER SPONSOR

Supported by: Supported by:

PILE THEM HIGH, SELL THEM CHEAP

Container volumes can move from transhipment port to transhipment port in big volume amounts. Steve Wray of WSP considers how Sri Lanka’s hub port aims could be realised going forward

Pile high and sell cheap applies to a container transhipment hub. Volumes can be large, and shifted to the terminal quickly, but the handling rates often achieved are lower than charged for origin and destination gateway cargo.

The requirements for a transhipment hub port are straightforward. Ports fall into different categories as far as their natural market is concerned. The location and cargohandling facilities of each port dictate which type of traffic it can compete for, and therefore defines its role in the market. For transhipment ports, geographic location and proximity to sailing routes is crucial. To be close to shipping lanes means that large and expensive ships do not incur extra costs for having to deviate to the port.

Other factors include the ability to call to modern terminals with easy physical access, offering deep water with immediate berthing available - and then be serviced by large cranes, with good productivity from a flexible and committed workforce.

Other important factors are availability of future capacity and avoidance of congestion, plus good support services (such as tugs and pilots). The ability to also bring some local import-export cargo is a bonus, too. Finally, a competitive tariff, with good discounts offered and linked to volume guarantees.

There are many examples of successful container transhipment hub ports around the world, but there are also ports and terminals that have struggled to attract cargo and also other facilities that have seen large chunks of their throughput disappear quickly – and often to another hub in the same region.

Whereas gateway demand is directly related to economic development in a port’s hinterland, transhipment demand is related to a broader, regional market, and hence to economic development in the transhipment region. In addition,

shipping cost calculations for direct versus feedered delivery are also determinants of demand.

Increases in both container port demand and vessel sizes have acted as catalysts to the development of transhipment. It allows carriers to benefit from the scale economies available from the introduction of increasingly large vessels on long-haul, high-volume trades, whilst also serving local ports, with smaller trade volumes and more restricted vessel access, by means of smaller feeder vessels.

Transhipment is significant in the Indian Sub-Continent port market, serving East Africa, the Bay of Bengal and Indian Ocean. Typical transhipment hubs for this region include Port Klang, Singapore, Tanjung Pelepas, Chennai and Colombo, as well as future potential at Hambantota

It should be noted that the level of transhipment will depend on the decisions of carriers about how they organise their service networks, to combine scale economies with maximised loadings and geographic coverage, not only underlying economic and container trade growth.

So, what is the current situation for transhipment in Colombo, as a well-established and utilised transhipment hub?

Sri Lanka forecasts were downgraded due to a terrorist attack in early 2019 and this had an adverse impact on a short-term consumption and investment. Although a weaker 2019 occurred, the IMF is expecting GDP growth in 2020- 2021 to return to previous levels of around 4%.

Of course, GDP growth is more relevant for internal consumption and likely import-export demand, although social unrest in any country will impact cargo activity, even transhipment.

8 Shipping company involvement in Sri Lanka can help increase cargo “stickiness”

8 Steve Wray, Associate Director, WSP

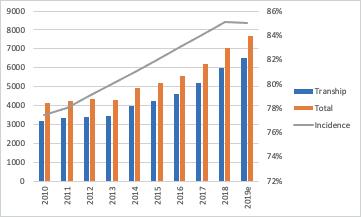

The 2019 transhipment and container volumes need to be put into context and the longer-term position should be considered as a better reflection on the port’s development. As Figure 1 identifies, there has been continued and ongoing growth since 2010, with the estimated total for 2019 of over 7.65 million TEU in total and 6.51 million TEU of transhipment.

These estimated totals reflect growth of 7.1% per annum between 2010 and 2019e, with the transhipment portion slightly higher at 8.2% per annum and follows strong growth of 15.8% in 2018.

Colombo continues to thrive on Indian Sub-Continent transhipment and East-West Relay containers, which collectively are behind recent demand improvements.

This success and a need for more capacity gave the Sri Lanka Government the necessary drive to further develop this port sector with the introduction of Hambantota, which had already been converted into a deepwater port in 2008. In 2017, Sri Lanka Port Authority signed an agreement with China Merchants Ports Group to convert Hambantota International Port into a public, private partnership.

The Hambantota International Port is managed by Hambantota International Port Group (HIPG) and Hambantota International Port Services (HIPS), two new companies set up under a PPP between China Merchant Port Holdings (CMPort) and the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA). The concession runs for a period of 99 years.

The recently announced deal in which CMPort and French Container Shipping Company, CMA CGM, entered into the Master Agreement which means that the jointly owned business, Terminal Link, acquired an interest in 10 terminals owned by CMA CGM for $955 million, was announced by HIPG. As such, it can be assumed that the Hambantota port facility is also part of the new arrangement.

Looking at the other container-handling facilities, there are several options, but the infrastructure is becoming more limiting: 5 Jaya Container Terminal has 1,292m of quay and 1 x 350m feeder berth, but water depth is 12.0-15.0m. 5 U nity Terminal has more limited water depths of 9,0-11.0m and a 590m of quay, though this option is not geared for larger container vessels moving transhipment units. 5 South Asia gateway Terminal (SAGT) has 940m of quay and 9 x Super Post Panamax cranes, but water depth is 15m, so more limited for the sizes of ships being introduced into East-West trades, although both APM Terminals and an Evergreen Marine subsidiary have a stake in the management company. 5 Colombo International Container Terminal can offer 18m of water depth, largescale terminal infrastructure and the ability to serve 18,000 TEU ships – however, fully laden ships that are now over 22,000 TEU will be more of an issue. This very short summary of the port’s terminals underlines that as container ships on the major East-West trades continue to increase in size, so the pressure on ports grows too. A port that is unable to successfully receive the largest ships will find its competitiveness impacted.

The Port Authority is studying the Colombo North Port option as part of a 30-year plan to raise annual capacity from 12 million TEU to 35 million TEU.

A challenge for any hub port is to look to entice the cargo and make it more “sticky” to the port directly. Where there is a large local market to serve will also help the ship to call because this is demand that needs to be served. Jebel Ali in Dubai is a good example here. Despite its deviation from the main shipping routes, major liner Alliances will make the sailing for the local demand and load transhipment cargo too for discharge.

Colombo does not benefit from a large local population, due to it being an island facility. This means that other “pull” factors must be generated to help attract and retain the cargo. This is a longstanding and frequent challenge that all transhipment ports face, even the most successful ones.

For example, Tanger Med has seen rapid growth since it opened in 2007, reaching 2.0 million TEU by 2010 and seeing subsequent increases of 8.9% per annum between 2010 and 2019. Yet the port authority remains keen to reduce exposure to transhipment which still accounts for around 90% of all port volumes.

As the market for Sri Lanka’s transshipment activities moves back towards equilibrium, after the next wave of newbuilds have been introduced, it can be anticipated that port concentration will be reasserted. Faster deep-sea services will be reintroduced and pressure to increase feedering and transshipment will intensify. Establishment of correct network solutions in advance of these developments will be in the interests of the major lines and will influence the size of vessels deployed on main and secondary trade lanes. One policy that hub ports can adopt is to secure terminal ownership and equity arrangements with container shipping lines, mainly because the ocean carrier will want to bring its own cargo to its own facility.

The arrangement between CMPort and CMA CGM may be a good policy for transhipment in Sri Lanka to supplement the involvement of APM terminals and Peony Investments (a subsidiary of Evergreen Marine Corporation) at SAGT.

8 Figure 1: Transhipment and Total Container Volumes at Colombo in ‘000 TEU, 2010-2019

8 Colombo: Infrastructure at some terminals is becoming limited

CAN INDIA’S EAST COAST CORRIDOR PROJECT SUCCEED?

Gordon Feller asks whether the much talked about, but not yet fully developed, desire to introduce coastal corridors along India’s substantial coastline might hold water

The East Coast Economic Corridor (ECEC) is India’s first coastal corridor and an example of what economists sometimes call “an integrated economic development initiative”. The key idea behind this corridor is to have port-based industrial development along the eastern coastal belt of India.

For a long time, the national government in Delhi has been keen to exploit India’s 7,500 km-long coastline, along with the 14,500 km of potentially navigable waterways.

The ECEC’s development program starts with the launch of the Vizag–Chennai Industrial Corridor. The VCIC is ambitious, covering approximately 800 km and including several port clusters, as well as major industrial zones.

India’s national government is attaching great importance to both the ECEC and VCIC and the overall objective is simple – to improve shipping and air connectivity in ECEC and VCIC. However, this will require something that is hard to do inside India, namely develop an enabling environment for efficient logistics support businesses. In short, it means establishing businesses that play a critical role in the management of global supply chains.

CLEARING OBSTACLES A number of obstacles inside the national and state-level governments and private sector enterprises, currently inhibit the growth of connectivity and investment in logistics services, rather than only physical infrastructure for individual ports and airports.

Specific proposals have been made to clear away obstacles, including items such as policy reforms to support development of a major hub port on the eastern coast of India and a major air cargo hub at Chennai, the streamlining of customs procedures and removal of protective measures in road freight markets and the establishment of Free Trade and Warehousing Zones. ECEC has certain distinct advantages for the development of ports, including India’s eastern coast offering relatively deeper drafts that can support the new breed of larger container ships and supertankers. It also offers an existing rail and road spine that is relatively better developed than its western counterpart.

However, India’s historical focus on trade with partners to its west—and the trajectory of industrialization that has put most of the traded goods that require containerization (as opposed to bulk) in the natural hinterland of its western coast ports—means that ports on the eastern coast handle very little container cargo.

INDUSTRIAL ORIENTATION The ECEC’s industrial orientation, which includes VCIC, is focused on sectors that require breakbulk and other forms of non-containerized shipping solutions.

The presence of minerals-producing areas in this region has led to significant investment in metallurgical and nonmetallic minerals-based industries over the past five decades, which is a trend that is continuing. Existing data for 2008–2013 shows that three of the top six most important industrial sectors in terms of investment and industrial growth were resource-based activities that require breakbulk solutions both for inputs and outbound final products.

These industries are chemicals and petrochemicals, metallurgy, and nonmetallic mineral industries. The other three include information technology, which has limited shipping and logistical requirements, textiles and automobiles and automotive parts.

While textiles and automobiles and automotive parts require containerised solutions, these industries are clustered around Chennai, which is the only port in ECEC that handles any significant volume of containers.

8 Obstacles in India must be cleared if coastal corridors have any hope in succeeding

Hot or not? Worry no longer.

With Reefer Runner, automated monitoring of refrigerated containers is as easy as handling dry containers.

www.identecsolutions.com Visibility Delivered.

SABIK MARINE - WE SHOW THE WAY

Coast guards, marine authorities, navies, and ports around the globe trust our efficient and cost-effective high-quality solutions. We are the leading global manufacturer of marine signals. Contact us for more information how we could support you in your marine projects

sales@sabik-marine.com www.sabik-marine.com

AD_Portsstrategy_TOC-Americas_OKT19_132x90mm_PRINT.indd 1 27.02.2020 16:13:12

The logical outcome of such an industrial orientation is that, with the exception of Chennai and Kattupalli, the main focus of ECEC ports is break-bulk and raw materials, such as petroleum, oil and lubricants, coal, iron ore, fertilizer and agricultural raw materials.

For VCIC ports, coal and iron ore collectively account for about 57% of total throughput, with liquids and petroleum, oil, and lubricants comprising 12, general cargo a share of 26% and container traffic a mere 5%.

The newly developed ports of Gangavaram and Krishnapatnam are heavily dependent on coal, which accounts for 80% of all traffic. The four VCIC ports located in Andhra Pradesh, Vishakhapatnam, Gangavaram, Kakinada, and Krishnapatnam, account for just 3%–4% of India’s total container cargo volume.

GOVERNMENT PREDICTIONS OF 3.0-7.5X EXPANSION The government’s own VCIC analysis predicts an expansion in industrial output of approximately 3.0–7.5x over the next 25 years under different scenarios. Such growth will create significant additional demand for containerised cargo solutions in the corridor’s ports.

While a “business-as- usual” scenario would increase the share of VCIC ports in India’s total container traffic handling to about 6% by 2020, new investments in sectors that require container-based evacuation solutions could see this share increase more significantly.

However, relatively low container-based cargo volumes currently translate into a lack of business interest for developing regular liner connections originating from India’s eastern ports, especially VCIC ports.

Except for Chennai, none of the eastern coast’s ports have direct liner services to major economic nodes in Southeast Asia or East Asia. The focus of eastern coast ports on bulk is also reflected in the fact that most ECEC and VCIC ports are much better connected by bulk and petroleum, oil and lubricant routes with Southeast Asia and East Asia than with container liner shipping and feeder routes.

8 The Sagarmala Programme wants to extend Indian value-chains to Asia

NEED FOR SHIPPING LINKAGES Integrating with global production networks cannot be achieved without establishing low-cost containerised shipping linkages with major global and (especially) regional industrial nodes in Southeast Asia and East Asia.

Regular, cost-effective connectivity with Southeast Asia and East Asia are an essential condition for the development of VCIC and the larger ECEC. This can be viewed as an example of the “chicken-and-the-egg” problem; that is, liner connections require that high trade volumes be present, yet (in some ways) having liner connections creates the enabling environment needed to establish such volumes.

Sagarmala Programme Goals

The ECEC aims to be in alignment with the goals of the Sagarmala Programme, which is focused on the integration of India’s industrial clusters with value chains extending to Southeast Asia and East Asia. Sagarmala is an initiative of the national government of India which aims to enhance the performance of the country’s logistics sector through unlocking the potential of waterways and the coastline to minimise the infrastructure investments required to meet these targets.

In 2018 the government said that Sagarmala will require an investment of 8.5 trillion rupees. This spend will be used to set up new mega-ports, to modernize India’s existing ports, development of 14 “Coastal Economic Zones” and “Coastal Employment Units” while enhancing port connectivity via road, rail, multi-modal logistics parks, pipelines and waterways and, finally, promoting coastal community development.

This is a significant amount to invest and if undertaken the government estimates that it would boost merchandise exports by US$110 billion and generate approximately 10,000,000 new direct jobs, and indirect jobs. Sagarmala is the flagship initiative of India’s national Ministry of Shipping and designed to promote port-led development. It is focused on modernising India’s ports so that port-led development can be augmented, and coastlines can be developed in ways that contribute to India’s economic growth.

Sagarmala aims to accomplish two goals, namely transform existing ports into what can be defined as “modern world-class ports” while integrating future development of ports, industrial clusters and hinterlands through road, rail, inland and coastal waterways – with the ultimate outcome seeing ports becoming “the drivers of economic activity” in India’s coastal areas. The successful development of ECEC is also critical to India’s Act East Policy, which focuses on connectivity agreements in South Asia and Southeast Asia such as the Bangladesh–Bhutan–India–Nepal Motor Vehicles Agreement, and the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation.

ECEC will be integrated with existing infrastructure development and upgrading initiatives at its starting and end points of Kolkata and Tuticorin, respectively, which are already part of the Golden Quadrilateral highway development program.

In the regional context of South Asia and the intra-regional role of South Asia–Southeast Asia (covering the Bay of Bengal-adjacent regions of southern and eastern India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Myanmar, and Thailand), relatively poor physical connectivity and the resulting high transaction costs have ensured that production network linkages remain weak. The relatively low volumes of intra-South Asian trade, in turn, reduce the incentive for logistics firms to provide e ffective and low-cost connectivity and value-added services.

This has the effect of further increasing the transaction costs associated with developing effective production networks. The relatively well-connected nodes of Chennai, peninsular Malaysia, and Singapore have helped develop robust linkages between India and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations within wider Asian and global production networks, particularly for automobiles and automotive parts, chemicals, and textiles.