16 minute read

SOUTH RIVER WATERSHED JACQUELINE ECHOLS

interviewed by Sorrel Inman

THE

Advertisement

Sorrel Inman What brought you into the ecological activism you have been doing in Atlanta for so many years?

Jacqueline Echols My involvement in Atlanta’s environmental issues began in 1997 while I was a graduate instructor at Clark Atlanta University in the Public Administration Department. During that year, the City of Atlanta entered into a federal Clean Water Act consent decree with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Upper Chattahoochee Riverkeeper.

This consent decree is a legal action taken by the EPA to compel a municipality to comply with the Clean Water Act (CWA). This action required Atlanta to stop polluting the Chattahoochee River with sewage from its combined sewer system—an antiquated wastewater system where sewage and stormwater are collected in the same pipe when it rains and discharge into local waterways. These sewage discharges receive minimal treatment and oftentimes bypass treatment altogether. Combined sewer systems are a relic from the past, built in the 1800s to carry sewage away from Atlanta’s growing “urban” area. The South River was Atlanta’s first combined sewer. Municipalities, like Atlanta, are allowed to continue operations with the caveat that discharges do not violate water-quality standards, which can trigger a response from the Georgia Environmental Protection Division (GA EPD).

Given the number of Clean Water Act violations that occur nationwide each year, a consent decree usually happens only once in a lifetime. I became a member and principal spokesperson for the Clean Stream Task Force (Task Force), a community-based group of environmental volunteers, in 1998. The Upper Chattahoochee River consent decree was viewed as an opportunity to force Atlanta to replace its polluting combined sewer system with a modern, twentyfirst-century separated (two-pipe structure) system that captured stormwater in one pipe and sewage in another.

The South River was not the focus of the Riverkeeper consent decree even though Atlanta’s combined sewer system also discharged into the river. South River Water Alliance’s (SRWA) involvement brought much-needed attention to the plight of the river, which had up to this time been ignored by the state’s environmental regulatory enforcement agency.

There are many, many Clean Water Act violations that take place across this country each year, and many have persisted for years, even decades, before resulting in a federally backed legal challenge. In 1997, Atlanta operated approximately nineteen miles of combined sewer, and their initial plan included zero sewer separation.

The majority of the combined sewer overflow discharges from Atlanta’s system were released into streams that flow through predominantly Black low-tomoderate-income communities in both the Chattahoochee and South River watersheds. Redressing this environmental justice issue became the focus of the Task Force’s advocacy, with the goal of separating all nineteen miles of combined sewer and replacing it with a modern twopiped system.

At the end of several years of direct action and indirect advocacy, the EPA agreed that the Task Force’s environmental justice claim of disparate impact on communities of color was substantiated. However, the agency declared in its infamous July 20, 2001, letter to the Task Force that these impacts were “justified.” This ruling effectively meant that Atlanta did not have to consider environmental justice impacts when developing its plan to meet the requirements of the consent decree. Effectively getting the green light to continue operating its combined sewer system without even considering any sewer separation. Fortunately, the EPA’s decision was countermanded by a followup decision by the Department of Justice requiring Atlanta to separate 50 percent of its combined sewer system in environmental-justice communities. Today, only nine miles of this antiquated system remains.

S: What gave rise to SRWA? Was there a specific event that led to its founding? What have been some important milestones along the way?

Echols In 1999, the call to action for the newly organized SRWA was in response to the looming crisis surrounding one of the seven landfills scattered throughout the communities near the South River. Live Oak Landfill had reached capacity and was scheduled for closure until the owner decided to seek permission from the state’s environmental regulatory agency to expand the facility. Receiving assistance from Green Law, a probono environmental law firm, SRWA won the fight, and the landfill was finally closed in 2002.

The South River is sixty miles long, beginning to end, and is hardly noticeable on a state map. The river has never met state water-quality standards until 2022, when SRWA forced the issue with GA EPD through the federal Triennial review process mandated under the CWA. This review requires that states manage waterways, including water quality, based on how citizens use it. As a result, thirteen miles of the river were approved for recreation for the first time ever.

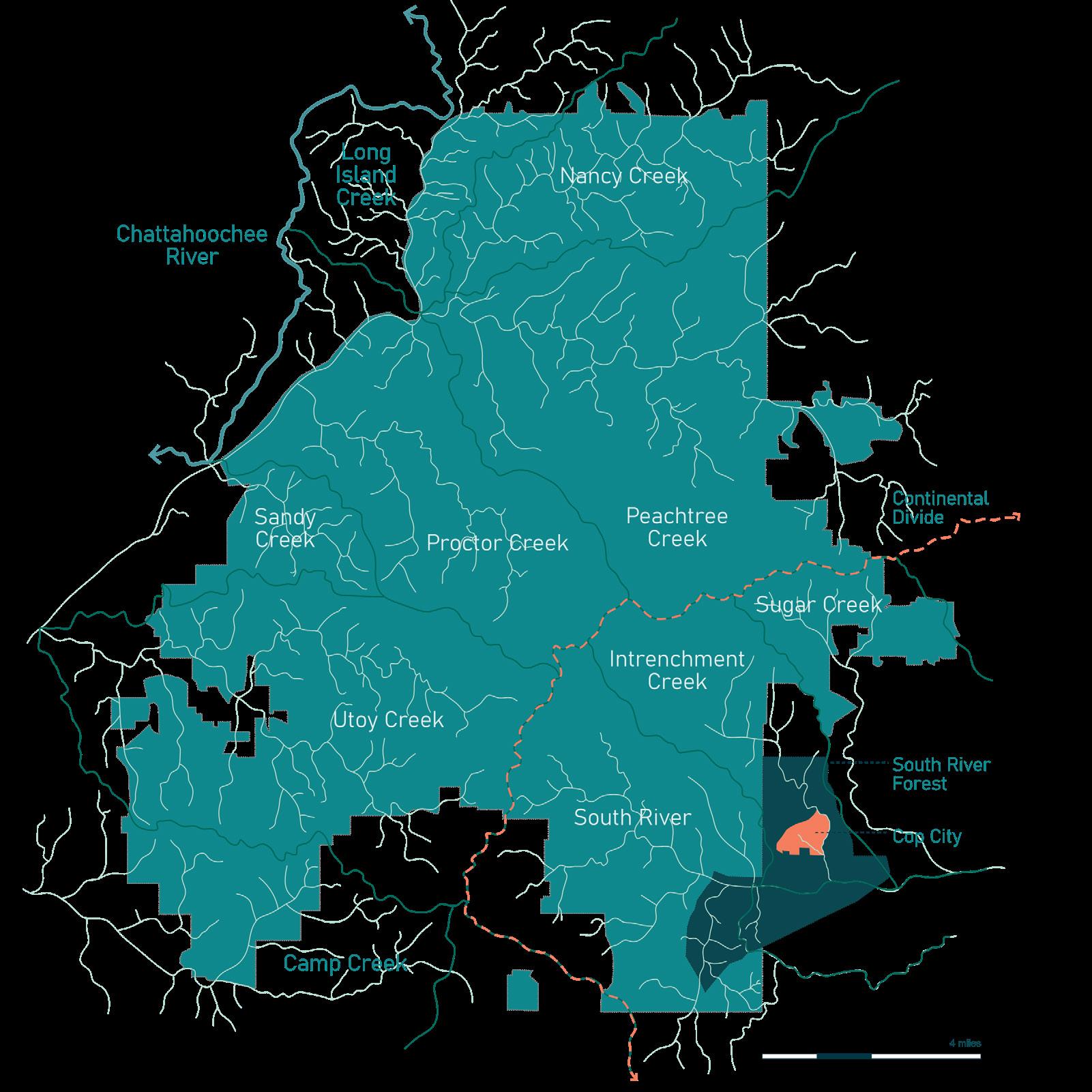

The South River has benefited from the strengths of early grassroots community advocacy and the community–river connection that clearly linked the health and welfare of neighborhoods along the river to the river itself. Early relentless and unchecked degradation of the South River has done more to weaken the fabric of support for the river than any other factor. The history of degradation has created a ‘culture of avoidance.’ Today, the belief that the river should be avoided poses the greatest threat to its recovery because recreational use helps to strengthen a sense of relationship between the community and the river, an essential component for motivating the improvement of water quality. local watersheds Intrenchment Creek and the South River relative to the rest of Atlanta’s watersheds and the proposed site for Cop City.

The earliest opportunity for SRWA to engage in real and effective collaboration in support of the South River followed closely on the heels of the landfill closure with the establishment of a task force led by the DeKalb County CEO’s office. Their charge was to make recommendations concerning the restoration of the river that coincided with a US Army Corps of Engineers study of the river and several of its tributaries that began in 2002 and was to continue through 2010. The Indian, Sugar, Intrenchment, and Snapfinger Creeks Ecosystem Restoration Project was commissioned to improve these aquatic ecosystems.. To date, the first two phases of the study— reconnaissance and feasibility—have been completed. The remaining phases—project authorization by Congress, plans and specifications, and construction—are on hold.

The Corps’ study was suspended in the spring of 2010 due to internal turmoil. As a result, DeKalb County decided to pull out of the study. Today, the study remains at a standstill, though there seems to be interest in its revival.

In 2011, SRWA was allowed by the federal court to intervene in the recently approved DeKalb County consent decree negotiated between the county and the EPA, mentioned above. This legal action was taken to ensure “standing” in the event SRWA decided to pursue further legal action at the end of the ten-year consent order. Pollution of the river began in the early 1960s and continued for fifty years, with little notice or action by the Georgia Environmental Protection Division or the EPA. If history repeated itself and regulatory agencies continued to fail, SRWA would be the river’s only hope.

S: Can you provide a history, as you understand it, of the large forest remnant that is under threat?

Echols The Old Atlanta Prison Farm was an abandoned 300-acre city-owned prison complex in southeast Dekalb County. Over time, the land has been used for several purposes including farming. From approximately 1920 to 1990, the land was worked by prisoners to produce food for the region’s prison system.

In urban areas, people do not exist separately from their environment—the two are inextricably linked. The forest and surrounding communities live together in an environmentaljustice milieu. The threat to the forest today that has captured the attention of the world originates from a pattern of historic environmental and social injustices that center on the South River and the river's major urban tributary, Intrenchment Creek.

Today, the site is a “recovering,” or successional, forest that reclaimed the land after the correctional facility was closed. In recent history, the site has been used as a training ground for the Atlanta Police Department for target practice and practice handling and detonating explosives. As one might expect, the lack of care and respect for the greenspace has also invited other degrading activities such as illegal dumping.

Likely the earliest effort to draw attention to and protect the site was in 2016. An initiative called Save the Old Prison Farm was an effort organized online and led by several southeast Atlanta residents who used the site for recreation on a regular basis and recognized its value.

In 2017, the Atlanta City Council voted unanimously to adopt the Atlanta City Design: Aspiring to the Beloved Community into the Atlanta City Charter. This plan envisioned the establishment of a public space referred to as South River Park. The plan included the creation of a 1,200-acre open space that would incorporate the prison farm. It is important to note that both of Atlanta’s rivers—the Chattahoochee River and the South River—are included in the Aspiring to the Beloved Community plan, but with entirely different outcomes. The Chattahoochee project, where a more affluent population lives, is moving ahead, while the South River project, where neighborhoods are home to poorer and marginalized people, has been left behind.

S: Building on that, could you describe the evolution of the two separate developments now threatening the Atlanta Forest and Weelaunee People's Park (Cop City and Ryan Millsap's)?

Echols These two developments [Cop City and Blackhall Studios] almost occurred in tandem. They did not evolve or develop gradually; they happened over a brief ten-year period.

The 2010 DeKalb County federal consent decree does not impose a deadline for DeKalb County to stop sanitary sewage spills in “non- priority” areas primarily concentrated in predominantly Black south DeKalb County. The consent decree does contain a deadline to repair the sewer system in predominantly White “priority areas.” This denial violates the 1972 Clean Water Act, the 1964 Civil Rights Act, as well as equal protection under the law. Building on the momentum provided by the consent decree debacle, the threat to the South River Forest (Atlanta Forest) and Weelaunee People’s Park is not at all surprising. The chain of decisions leading from the county’s initial disinvestment to the emergence of Cop City and Ryan Millsap’s Blackhall Studios provides a vivid example of how vulnerable and resource-deprived communities can be quickly consumed by inequity. These communities are the least able to fight off such acts of violence.

In 2020, DeKalb County executed a land swap, which gave forty acres of Intrenchment Creek Park’s (ICP) 136 acres to Blackhall Studios. Intrenchment Creek has been an integral part of the county’s greenspace plans, previously described to a potential funder as “satisfying the need for much needed open space for park land as well as protection of an important tributary to the South River.” The description continued, “Given its location on Intrenchment Creek and the shortage of expansive property remaining in this area, the County considers this site to be extremely important.” The greenspace that became ICP was purchased in 2002. In a moment of cruel irony, the county used its own twenty-year failure to invest in the park and the surrounding community as justification for the swap.

The potential loss of ICP was compounded in 2020 when the City of Atlanta authorized the construction of a police training facility on eighty-five acres of the prison farm greenspace. Reportedly, discussions between the City of Atlanta and Atlanta Police Foundation began in 2017. The handling of the circumstances surrounding the death of Rayshard Brooks by Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms in 2020 strained the city’s relationship with the police force and police union. The gifting of the city’s largest remaining public greenspace to the Atlanta Police Foundation was viewed as an effort to help mend the rift and improve police morale. In 2022, a review of the land disturbance permit by South River Watershed Alliance submitted to DeKalb County for approval revealed the 85-acre site had morphed to 171 acres, more than double in size and consuming more than half of the 300-acre greenspace. This enormous increase is not authorized by and is inconsistent with the ordinance passed by the Atlanta City Council. These land transactions threaten the two largest contiguous parcels of publicly owned greenspace inside I-285, the interstate system that encircles Atlanta.

S: What connections, ecological and/or social, led to SRWA being a leading voice in the opposition to Cop City?

Echols When tackling an issue like environmental justice, perspective accounts for a lot, if not everything. It is much easier to fight for an issue that you believe in because you understand it as a result of lived experience—in other words, from the inside out. In reality, the right to a safe and healthy environment exists more for some and less for others. Disparities persist. Inequities are likely to be more prevalent in urban areas where people are more concentrated, especially poor and marginalized populations.

For more than six decades, public outlays or investments in upper South River communities have been minimal. However, in a relatively brief ten-year period (2010–2021), they have been denied or stripped of their most lucrative public assets. Disinvestment of this magnitude exacerbates inequality and threatens to undermine any possibility of sustainable economic or environmental recovery these assets could have provided. The role of government in fueling and promoting actions that result in discrimination and injustice, at this level, sends a disturbing message relative to the ability of these local governments to act fairly, equitably, and in the best interest of all citizens.

In urban areas, people do not exist separately from their environment— the two are inextricably linked. The forest and surrounding communities live together in an environmentaljustice milieu. The threat to the forest today that has captured the attention of the world originates from a pattern of historic environmental and social injustices that center on the South River and the river’s major urban tributary, Intrenchment Creek.

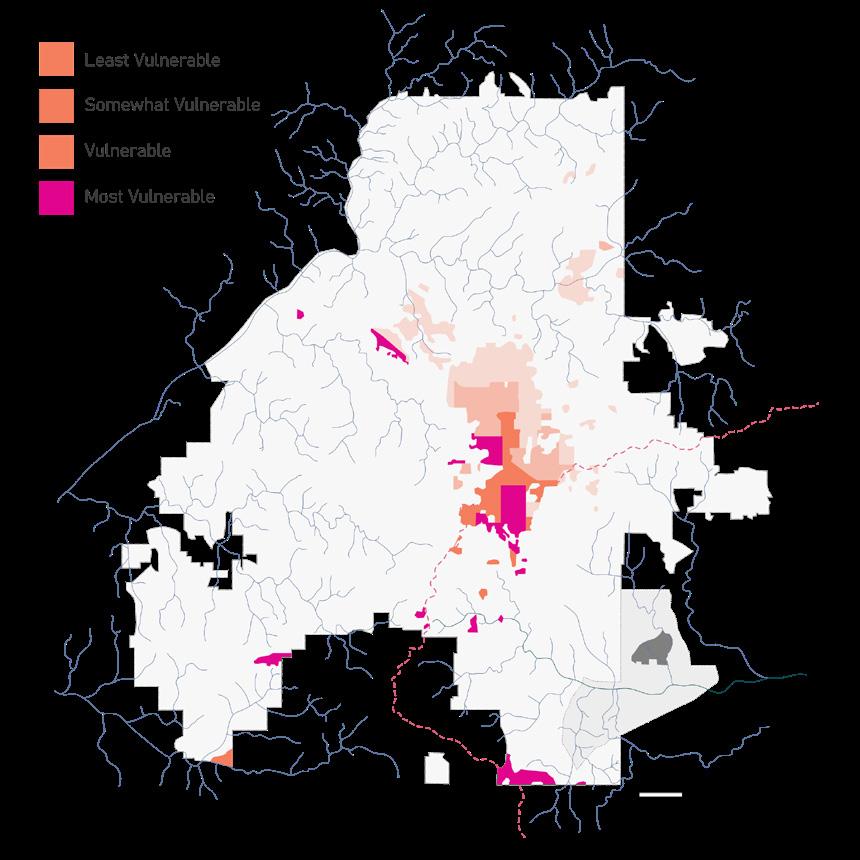

One of the main purposes of government is to address problems of fairness or access experienced by citizens. This mandate would seem to focus the support of the City of Atlanta and DeKalb County on disadvantaged areas, particularly given the racial makeup of constituents and political leadership. However, this has not been the case. There has been and continues to be significant gaps between the recognition of need and formulation of investment policy to address that need. It bears emphasizing that the main source of threats has not been from private development, which one might expect, but local government. The opportunities that were seized upon the Blackhall Studios (Ryan Millsap) and the Atlanta Police Foundation would not have been possible without the consent and acceptance of the City of Atlanta and DeKalb County. heat-island effect vulnerability The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed a Social Vulnerability Index using demographic factors such as socioeconomic status, household composition and disability, minority status, and others. Higher vulnerability refers to conditions of exacerbated environmental stresses on human health and wellbeing.

Even as the South River, designated by American Rivers in 2021 as one of the ten most endangered rivers in the United States, stages a comeback, unprecedented governmentsponsored disinvestment by the City of Atlanta and DeKalb County threatens any hope of revitalization and recovery. These assets are colocated, increasing their collective positive value for the community. On the other hand, it also intensifies their vulnerability to the negative “ripple effects” of disinvestment. The loss of a single community asset of this magnitude is rare. The loss of three in such close proximity to each other is inconceivable, unjust, and will result in irreparable harm.

S: Building on that, what services does this large forest remnant provide for the community in terms of stormwater absorption, habitat, community health, or any other benefits? Could you summarize the ecological stakes pertaining to the destruction of the Atlanta Forest for the infrastructure proposed by APF, APD, and the City of Atlanta?

Echols Health disparities in environmental-justice communities are well documented and relate to disproportionate environmental costs such as water and air pollution, lead contamination, heat-island effects, ozone smog, and other hazards. Surrounding neighborhoods are already burdened with pollution from countless “big rig” and numerous other land-based trucking and hauling businesses that wreak havoc on air quality. The City of Atlanta has not addressed, in any meaningful way, the compounding of negative health impacts related to the training facility and the loss of tree canopy on surrounding communities. Both the City of Atlanta and the Atlanta Police Foundation are fixated on mitigations—specifically, the claim of replanting 100 trees for each tree destroyed and the absence of “old growth” trees on the site as the litmus test for preservation. Neither of which addresses the inevitable community-health impacts in any way.

Additionally, the total acreage of the prison farm site (297 acres) and contiguous Intrenchment Creek Park (136 acres) greenspace is the largest remaining parcel inside I-285, the interstate beltway around Atlanta. The tree canopies located within the South River Park and Chattahoochee River Park are described in the Atlanta City Design: Aspiring to the Beloved Community plan as equivalent to Atlanta’s lungs and the last big greenspaces to save. The excerpt below is from an August 22, 2022, follow-up letter to the chairperson of the board of directors for Cox Enterprises. It puts into perspective the tenuous relationship decision makers, both public and private, have with the environment that protects southeast Atlanta.

The justification for clearcutting the Prison Farm Forest, destroying thousands of trees, is that the forest contains only “one” old-growth tree. Any discussion related to the protection of trees in Atlanta, on this site or any other, extends far beyond focus on a single tree, regardless of size and age. Climate change is destroying our air and water, both of which we need to survive. At present, our best defense against a future of worsening environmental ruin is to stop the destruction. Atlanta’s rapid pace of unbridled development is razing substantially more trees than are being replanted. The vast majority of trees are being replaced by saplings, which will meet old growth status in 100 years, if they are lucky and not cut again in the meantime. There is much concern over the number of trees the city loses to development each year—approximately 6,000 to 8,000 healthy trees per year—with FY 2021 being the highest to date with approximately 8,000 healthy trees cut. In FY 2022, that number jumped to 13,440 healthy, non-hazardous trees removed for development, an astounding number (Atlanta City Planning Department website). The development of the Prison Farm site alone will destroy many, many hundreds of healthy trees. If all we protected was old growth forest, we would have virtually nothing left. The successional forest at the Prison Farm provides significant ecological value, wildlife habitat, and riparian buffer that protects Intrenchment Creek. Let us not lose sight of the fact that the entire Appalachian Forest was timbered at the turn of the century. When not covered in concrete, a forest grows back.

Wildlife and their habitat have benefited enormously from the South River’s obscurity and endless bouts with pollution, which discouraged human interaction. The river’s longstanding pollution issues also curbed interests in downstream development as well, thus enabling habitat to flourish, creating a fifty-mile wildlife corridor along the South River from the Atlanta Forest to Jackson Lake where the river ends. Today, innumerable species of terrestrial, aquatic, and bird life inhabit and use the connectivity of the river and Intrenchment Creek to safely navigate up and down the river—making the Atlanta Forest an excellent setting for viewing wildlife. The planned development of the Atlanta Forest will destroy this urban-most habitat.

S: Could you describe the sociopolitical stakes pertaining to the destruction of the Atlanta Forest and the development of Cop City? Earlier, you mentioned disinvestment to describe the racism at the heart of the push to build Cop City on this site. Can you expand on that by providing specific examples of how the eventual execution of this project would lead to outcomes that represent environmental racism?

Echols As a political scientist by training, I have learned that the simplest way to describe and understand politics is to explore who gets what, when, how, and why—with the greatest emphasis being on who and why. In politics, affluence equals influence—and nothing is more political than the environment. If you do not live in a community, it is easy to be cavalier about what happens there. Nevertheless, for the people who do live there, it’s personal, very personal. It is easy for outsiders to tout environmental mitigation instead of protection. The Atlanta Police Foundation and its rich benefactors have done this as they parrot the ridiculous notion of planting 100 specimen trees for every one tree destroyed as suggested by the mayor’s office. The same government officials suggest that community members for whom the majority of personal wealth is invested in their homes support destroying the very environment upon which that wealth is based. Where is the model that supports the notion that a healthy thriving community can co-exist alongside a disruptive and environmentally destructive police training facility that will redefine health, welfare, and quality of life for residents 365 days a year, turning it into a living nightmare? And would this idea be proposed, much less considered, anywhere else outside of this environmental-justice community? More to the point, would it be considered in the wealthy community of Buckhead or anywhere west of downtown Atlanta?

Environmental racism is the unequal impact of environmental hazards on Black and marginalized communities. The police and fire training facility will be used to train recruits and existing police and fire personnel that protect and serve communities, not only within Atlanta, but also from across the country and world. Yet the impact of this facility will be borne by a single environmental-justice community.

Environmental restorations have both social and political implications. Environmental amenities such as greenspaces, rivers, and streams offer unmatched opportunities for revitalizing neighborhoods subjected to environmental injustice. More than any other factor, governing bodies strategically characterize natural areas as “degraded” in order to undermine efforts to protect and restore those areas. This is not only the case for the prison farm greenspace, but it is equally true pertaining to the decades of environmental degradation from south Atlanta to south DeKalb County. Environmental restoration can become the catalyst for revitalizing neighborhoods that have been subjected to environmental injustice.

Historical inequities are indelibly inscribed into the Atlanta Forest landscape and the communities that are a part of this geography. Disparities in the distribution of environmental amenities are a well-known and documented issue in vulnerable and marginalized neighborhoods. This reality has been unaffected by the color of those wielding political power and/ or influence in Atlanta. As a matter of fact, this is an issue wherein one might expect a decidedly different perspective, commitment, and outcome given the decades of Black political leadership in the City of Atlanta—one that addresses environmental and social-justice issues. To date, there is not an ordinance, resolution, or statement that has emerged from the city council or mayor’s office acknowledging race-based disparities, nor support for achieving environmental-justice goals, despite their popular support within the community.

If you care about the environment, people, communities, ethics, right and wrong, equity, justice, dishonesty, exploitation, the greater good, political arrogance, or corporate money on steroids— just to name a few—this is your struggle. I think many people, particularly those living outside of Atlanta, are surprised to find that these issues not only exist but to this magnitude in the “city too busy to hate.”

One does not have to be an environmentalist activist to find a comfortable place of resistance in this fight.