After that is our short story section called “Vignettes,” which gives readers a glimpse into the lives of five Miami students. From doing the dishes to bodybuilding to the pu ritans to academic burnout and working as a cashier, these stories teach us about the often overlooked parts of life.

Next is a personal narrative from the magazine’s Man aging Editor, GraciAnn Hicks, about a traumatic event at her summer internship. In “A Life Almost Taken, Mine Forever Changed,” Hicks walks us through her experience as a journalist working just buildings away from the at tempted murder of famous author Salman Rushdie.

Megan Miske earns the cover story spot with “Time to BeReal.” This reported piece reflects on various student opinions about the hot new social media app, BeReal, and aims to discover if it is as authentic as it may seem.

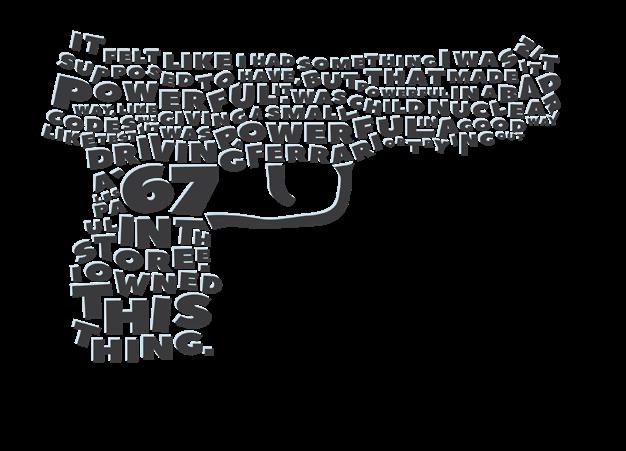

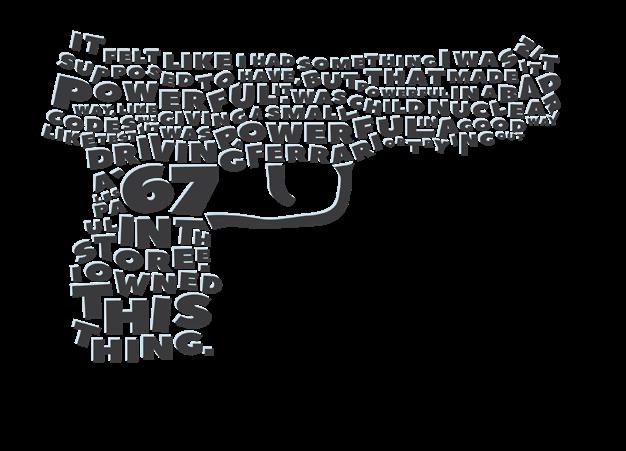

In the following story, Devin Ankeney writes about the complicated and personally conflicting experience of buy ing their first gun. Read all about it in “Dancing with the Second Amendment.”

Third to last is “Just Him and a Motor,” a profile from Henri Robbins. This profile teaches us about professor J. E. Elliott’s lifelong love for riding motorcycles.

“Entering the Red Zone” by Assistant Editor Claire Lordan comes next. In her reported opinion story, Lordan explains that first-year college students are at a higher risk of experiencing sexual assault or violence and pleads for schools to take action.

Finally, there is “My Traveling Words of Wisdom.” In this story, Charlotte Hudson shares excerpts from her trav el journal and explains how rereading each entry has al lowed her to better understand who she was, who she will be and who she is now.

While I have a long list of people to thank, I want to start by acknowledging all of the writers who volunteered their time and talents to The Miami Student Magazine this semester. Each of you has so much passion for your sto ries and your commitment to them will not go unnoticed. Thank you for making this issue possible.

Another massive shoutout goes to the editorial team: Managing Editor GraciAnn Hicks and Assistant Editors Meta Hoge, Hannah Horsington, Claire Lordan, and Jes sica Opfer. This publication would not be the same with out the knowledge, passion and curiosity that all of you brought to the table week after week. I am so profoundly grateful that you are a part of this team.

Finally, I’d like to thank our art director, Macey Cham berlin, and her incredible team of designers. Seeing the final art come together for the first time never gets old. An other thank you goes to the excellent photographers who worked with us on this issue. Together, all of you bring this magazine to life.

Overall, I cannot express how proud I am to be the Ed itor-in-Chief of this publication. Significant changes and new additions were made easy and possible because of every hard-working writer, editor, designer and photogra pher on this staff. You all are simply the best.

With that, it is my great honor to present Issue XI of The Miami Student Magazine

Now, get to reading!

Skyler Perry Editor-in-Chief

YOU HAVE THOUGHTS ON THIS ISSUE OF THE MAGAZINE? GIVE US FEEDBACK AT

DO

EIC.THEMIAMISTUDENTMAGAZINE@GMAIL.COM

The Face Behind the Fursuit

PROFILE

“I’m a furry,” she said.

My stomach dropped. I remember fear bubbling up as I looked away.

That’s what Sam Flake, a then first-year psychology major from southwest Ohio, told me. We were at a First 50 Days event at Miami University coloring premade tem plates with markers when she mentioned the fact and asked if I wanted to move in with her.

I had known her for only a couple of weeks, and now she was smiling at me in that nervous way people do when wait ing for an unknown answer.

“Uh … why are you telling me that?” I replied.

Sam posts her works-in-progress (WIPs) and recent com missions on her Instagram and Twitter @sheenitude. Sam’s pages are relatively popular — she’s gathered over 15,000 followers on Instagram and has about 5,000 followers on Twitter. Her YouTube page, Kyla Wolf, where she posts her WIPs and tutorials, has just under 7,500 subscribers.

She spends weeks detailing hand-sewn suits to be shipped all around the world. Her work is done through commissions only and the suits go for more than $5,500. While she only takes a handful at a time, each one can take up to months to finish.

Now, she didn’t tell me all of this infor mation just because she felt like it.

is to imagine furries as a kind of fandom, akin to something you would see around anime, comic books, or video games.

Furries’ interests just happen to overlap with the animal kingdom.

People who identify with the furry community usually create their own “fursona,” which is a character that has a unique identity and personality. Some people commission their fursonas to be made into fursuits, which are full-body outfits comparable to those of sports mascots. They are cre ated so that the customer can act out their fursona.

That’s where Sam comes in.

Sam isn’t just a furry. She’s a fursuit maker and a suc cessful one at that. Her business, Soul Enterprises, has gar nered quite the following over the past six years.

She wanted me to know because we were considering moving in together, and that would mean occasionally having the husk of a neon-colored animal hanging around, which would be a bit of an adjustment for any roommate.

I agreed to move in anyways.

Life with Sam was about what I expected. She worked constantly; her sewing machine was always whirring in the background of our lives. Sometimes I’d sit in bed and watch her work. We’d chat about what it was like going to conven tions, how to create fursona, or the problems she was having with a customer. Or she’d sit in silence, listening to music while she worked.

But no matter the distraction, her hands were always steady, intricately feeding the sewing machine or fastening one piece of fabric to another with a quick stitch. It was all about the details.

THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022 7

Illustrations by Erin Morgan & photos by Abby Bammerlin

We moved out after the pandemic caused shutdowns across the country. Miami sent its students home, so we went our separate ways. We still talked over text and occa sionally Facetime, but our conversations had become more about the world and less about fursuits.

But three years later, when I told Sam I wanted to write about her fursuits and her furry identity, she cringed.

“I don’t like saying it’s part of my identity,” she said. “I mean, it is, but I don’t like saying it.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“It’s just weird,” she said.

Sam wasn’t born into the furry universe. She didn’t just wake up one day and believe she was an animal — that’s not really how most furries discover the community.

For her, it started as a fun way to expand her art. When she was 14 years old, she stumbled upon some YouTube vid eos of a dance competition at a furry convention. At first, she was really put off by it.

“I was like, ‘This just looks weird. Why are these people dressing up like that?’” she said. “Which is fair.”

But then, two of the suits caught her eye. She started watching more videos created by these furries, and they in spired her to expand on her art.

Before long, Sam decided she wanted to explore sewing. Her mom was the sewing expert in her household, so natu rally, she was the one Sam turned to for help. She’d pester her mom repeatedly to show her a specific stitch until she finally gave in.

“She'd show me once and she's like, ‘Okay, go practice it a hundred times,’” Sam said. “It was horrible, but that was my practice.”

When she started creating suits, her mom couldn’t help anymore. Sam turned back to YouTube, but she could only find one video explaining how to make a head. For every thing else, she was on her own. Another problem Sam had was that she couldn’t exactly ask for help at her local sewing club on how to create a fursuit without getting a few eyebrow raises.

But slowly, using dress patterns and templates of her design, she developed her own method of bring ing fursonas to life.

She fixated on it, and what started as a casual interest in drawing became a full-fledged business. She’s created over 40 fursuits since 2016.

It’s important to note that not all furries are in it for the same reasons. Sam rolled her eyes when I asked her how she deals with the bestiality stereotype furries are given.

“I think it can be really hard to break down the stigma around it just because people want something to shit on,” she said with a laugh. “And furries are really easy to shit on.”

By and large, she doesn’t see her community focusing on sex. That side does exist, but it’s the minority.

There have been instances of online scams when buying and selling suits, as well as people abusing animals. But in Sam’s mind, there are bad people in every community.

“Our bad side is just more well-known,” she said.

She doesn’t tell many people about her hobby. She’s guarded around the topic. While her family knows and sup ports her, she’s told only a handful of close friends. She waits people out, weighing how they’ll take it.

MAGAZINE, FALL 2022 9

THE MIAMI STUDENT

“I usually sugarcoat that I'm gay until I know the person is OK with it,” Sam said. “I sugarcoat a lot of my normal per sonality traits because I’m autistic. Those two things already are really big parts of myself so it just doesn't make a huge difference to hide one more thing.”

Unfortunately, Sam’s fears surrounding the publicity of her hobby are justified. Since she started her business, she’s received so many death threats that she lists them off casual ly as if they’re grocery items.

“I've gotten people telling me to kill myself,” she said. “I've gotten people telling me that they're gonna come kill me or they hope I die. They hope I get in a car accident, peo ple telling me that I'm the scum of the earth, I'm the worst person alive, and that all furries should die.”

She rolled her eyes and laughed.

“All I do is, a few times a year, [I] dress in an animal cos tume and run around at a convention,” Sam said.

Before joining the community, Sam was quiet. She was the kind of kid who would dread speaking in class. When the teacher asked a question, she’d sink into her chair, eyes pointed to the ground, and try her best to disappear.

But then she started developing her fursona: a playful, spunky wolf character named Kyla who was the complete opposite of Sam's outward expression at the time.

“When I was in-suit during my first convention, I could act however I wanted, [I could act] like an idiot just having fun, and everyone loved it,” she said. “And everyone recipro cated that. And it was like, ‘Oh, shit, I can just have fun and everyone's digging it.’”

It took a few more years, but today, bits of Kyla’s person ality have become part of Sam’s.

When she gets to a new class, she scopes out new faces: potential friends. She lights up at mentions of shared hob bies, hailing down a slew of questions to find a closer con nection.

This is the process for many furries who have just dis covered the community: A feeling of isolation and rejection turned into acceptance and tolerance.

Now Sam can create that feeling for her clients as well. As an artist, she feels a sense of pride every time a customer sings her praises. Her work is not only appreciated but ad mired.

The excitement her customers feel when they unbox their new fursuit is understandable. For many, they feel comfort able only once the mask goes up.

“The character you're dressing up as is most often your idealized self or your true self,” she said. “And so when you put that on, you get to be that person. And no one knows any different.”

10 THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022

At the end of our interview, I started to wrap up our con versation. We laughed at a joke one of us made as I began to stand to leave.

“Oh hey, when is this piece coming out?” Sam asked.

“Honestly, I’m not sure,” I replied. “Maybe November or December. Why?”

“Oh, I was just worried about my professors seeing it and thinking, ‘Oh Sam …’”

Her voice trailed off. She smiled her ner vous smile, the same one she had the day she told me she was a furry.

I smiled back at her.

“That’s what the piece is for,” I said. “Maybe they’ll see it and think it’s cool or at least learns a little more about the community.”

“Yeah,” she said with a shrug. “Maybe.” S

***

Small Actions, Big Transformations

How clearing brush and climbing a mountain altered my world view

By

By

Sam Norton

Pickaxe in hand, I gazed at the massive blackberry bush in front of me. Concentrating on one spot, I swung and con nected right at the base. I stomped on the other end of the pickaxe and finally had enough leverage to yank the thorny, invasive plant out of the ground.

I turned around and tossed this bush onto a huge pile of other plants that my team and I had collected for the past two hours. We were clearing out a small stretch of forest along the Snoqualmie River, just south of the Cascade Range in central Washington.

I was sweaty, covered in burrs and sore from the same repeated swinging motion. It was only 10 a.m., but I was already hungry for lunch.

The dense vegetation of the Pacific Northwest en closed us, and after two hours of removing bushes, we were starting to see only small changes for what felt like a lifetime of work. As I geared up for the next bush in line, I wondered what the point of it all was.

14 THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022

PERSONAL HISTORY

Illustrations by Erin McGovern

GIVE offers trips to students all over the world, with a focus on sustainable volunteering. It works with local communities on specific projects to benefit those in need.

As an environmental science major and honors college student, I originally planned this trip to fulfill honors requirements and explore what ecological volunteering looks like. Although I initially intended to go alone, my girlfriend eventually decided to join me.

Despite her coming along, I was still nervous to travel farther from home than I ever had before and meet a bunch of new people I had to live with for a week.

After waiting nearly two months over summer break, I was finally about to begin the trip I had planned for months. Walking up the stairs of a random hostel in Se attle, I knew it was time to meet new people and adapt to a new city and state. I wondered about the kind of people I would meet and was slightly nervous that they would be hard to get along with.

Yet to my tremendous surprise, the people that greeted me that night were 20 exuberant college students with in fectious energy and friendliness. I was initially taken aback, but I quickly relaxed and engaged with them. I could feel myself starting to shed some of my preconceptions.

The next morning was early, as we had to commute an hour to our first volunteer site. My sluggishness quickly evaporated as I became immersed in conversation with my new companions and captivated by the views outside.

As we wound through highways and backroads alike, we were all amazed at the lush mountains that seemed to follow us wherever we went as we traveled north from Seattle.

With everyone coming from different parts of the country, it was incredible how our paths led us to this trip. I quickly learned that our reasons for volunteering were similar — mainly driven by a love of the outdoors.

We started removing blackberry bushes the second day. After arriving at the park, we grabbed the needed tools, hiked a short distance into the woods, where we soon reached the riverbank, and began hacking the thorny beasts out of the ground.

I was curious why removing invasive plants was so important, especially after seeing the effort it took. It felt insignificant when I looked down at the small part of the river and saw just how much vegetation there was. As we ended, our leader explained the purpose behind our work.

I learned that removing invasive plants clears more area, allowing the trees to become healthier and grow taller. This provides more shade to the river, raises oxy gen levels and is better for native salmon that return to their breeding grounds each year.

In that moment, everything clicked for me. I was amazed at the chain of positive environmental effects that could be triggered by removing what did not belong from an ecosystem, even if it was just one bush of an entire species.

THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022 15

***

On an ecological and personal level, it was incredi bly encouraging to see how this seemingly small effort from a bunch of college kids could substantially impact the world around us.

On the second day of volunteering, we removed invasive shrubs in an open field near our lodging. A constant buzzing filled the air as we worked under the powerlines that created a scar cutting through the otherwise pristine wilderness.

Despite this reminder of civilization directly overhead, nature still seemed to swallow us. Towering mountains in the distance rose above man's creation, and the expansive view looking down the hillside seemed to stretch on forever.

I was encouraged while working as we all discov ered a newfound resentment for the invasive plants taking over these precious ecosystems. We pushed each other to go after the biggest and baddest shrub we could find.

It was certainly not pretty or easy, but during this hard work, I got to know many of the other volun teers. We talked about anxieties related to college, past bad relationships, what it's like to scuba dive with dolphins, and many other intimate parts of life.

It felt good to talk in a judgment-free environment. Despite only knowing them for 48 hours, I felt wel comed and appreciated by the other volunteers.

These small conversations shaped the mood for rest of the week. I realized that I enjoyed these little moments of learning and growing with each other — something I had not expected when I landed in Seattle. ***

We stayed in a cabin in the middle of the woods for most of our trip. Although there was a crew there to serve us, ev eryone seemed to jump at an opportunity to help in any way possible. We cleaned dishes, chopped firewood, and swept without being asked.

One night, several volunteers and I decided to play the card game, “Apples to Apples.” What started as a way to pass time ended with most of us crying with laughter as we forced the judge to read out the description of every card.

It was one of those moments that you don’t even under stand what was so funny when looking back. All that matters is that, at the moment, it was one of the funniest things I had ever been a part of. In just a few days, these people from across the country I had never met became my great friends through these shared moments of joy.

I still find myself thinking back to those moments with fondness and admiration. It reminds me how important it is to surround myself with people willing to do the smallest things to make a difference. I now do my best to always find joy in helping others.

16 THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022

At this point in the trip, it seemed as if every waking moment was filled with laughter and sincere happiness. This environment was something I had not experienced since I was a kid in summer camp, and getting to create these bonds at this point in my life was surprising in the best way.

I saw change not only in myself but in my other friends. I was beginning to understand how important the intimate moments we had been sharing were.

On our third day of volunteering, we again worked on removing invasive blackberry plants along the Snoqualm ie, just a few miles upriver from the first day. That same afternoon, we went tubing down the river.

As we floated down the current, the tranquility of being on the water and the beautiful scenery of the Wash ington wilderness was a wonderful break from our hard work. Our leader reminded us that without the efforts of those like us who worked to keep the river healthy and clean, we would not be able to enjoy these activities.

We felt very proud to see how our work benefited the environment and the people who want to experience na ture as it should be. I have found that I am most at peace when surrounded by nature, and everyone should be able to have that experience.

On one of the last days, we took a break from volun teering to spend the day hiking to the top of Thorp Moun tain. I was excited at the prospect of reaching the nearly 6,000-foot summit to see the incredible views of Mount Rainier that the route is known for.

On previous hikes, I often only found satisfaction in completing the journey as quickly as possible instead of taking the time to appreciate the actual hike itself.

Yet, I forced myself to step back and slow down on this day. My girlfriend asked me to stay with her and others who didn’t want to race to the top, and I agreed.

We started our hike and began falling behind those in the front. I found myself experiencing a different aspect of this adventure. I was able to hold long conversations with others at this pace, and we stopped more often to appreciate the stunning nature that surrounded us even at the lower elevations of the mountain.

We were surrounded by a beautiful, pristine forest that could have come from a fairy tale. I felt humbled as I looked up at a canopy composed of towering pines, and I was taken aback by the delicate blanket of ferns and mosses that sprawled across the floor.

The combination of peace and wonder that I feel in places such as that forest always tugs at my heart and brings me back to nature. I felt truly grateful in that mo ment to experience these wonders of our planet.

As we got to the more strenuous parts of the hike, we started to struggle. There was light-hearted joking and complaining about the hike's difficulty.

SPRING 2022 17

THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE,

feel afterward and lied a bit about how much elevation gain was left.

As I pulled these words from within myself, the physi cal pain was second to the fun we all had together on this trail. I struggled to catch my breath as my lungs began to sting and legs started to burn, but we kept at it.

With sore calves and tight chests, we eventually got to a clearing where we were greeted with a sign that informed us we had a short, though steep, final stretch. After a water break, we pushed through a dense forest and finally made it out.

Like walking through a portal to another world, my breath was taken away by what my eyes beheld. The grand magnificence of Mount Rainier filled my view. Its snow-capped peak, cascading slopes, ridges and sheer massiveness still captivate me today. Its grandeur entranced me as I continued the trek, and I had to peel my eyes away to take in the beauty that immediately surrounded me.

Sprawling fields of wildflowers blanketed the slope, their bright colors in beautiful contrast to the scraggly green grass. The trail zigzagged back and forth as it con tinued up. At the base of the mountain, I saw a deep blue lake stretching across the landscape, perfectly framing the splendor of Mount Rainier. It took me a few minutes to snap out of my awe and finish the journey.

At the summit, Mount Rainier dominated the horizon to the south, while the jagged Glacier Peak and the end less green of the Okanogan-Wenatchee forest carved the landscape on all other sides. Nothing stood between us and God's majestic creation.

I realized on top of that mountain how good it felt to be a source of encouragement rather than racing against myself to the top. Suddenly I didn’t feel so small but rath er amazed that I could impact this incredible world and its people for the better.

It was the culmination of so many different moments throughout this trip that showed me over and over again how small actions could lead to huge, fulfilling change. I descended that mountain overjoyed, happy at how much I felt I had changed in just a few days, and proud of how our group, fondly named “Team Trail Mix,” stuck through our tough hike together.

***

A couple of days later, I was deeply saddened when I said goodbye to those I had become so close with over such a short period. I truly felt that I had connected indi vidually with every single other volunteer at one point or another, and I still miss our time together.

Yet when I look back on this trip, what tends to fill my mind more than the views from hikes is the small moments I experienced and the people I interacted with. I now realize that I can enact incredible change within myself, the environment and others, even if the changes seem small.

But that’s the thing: Small changes are everything.

18 THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022

Suddenly I didn’t feel so small but rather amazed that I could impact this incredible world andits people for the better.

PUPS WITH A PURPOSE

The life of service dogs in training and their student handlers

By Madalyn Willis

While dogs may be man’s best friend, they can also take on other roles like sniffing out danger, herding animals, or searching for people. In addition, some dogs can be trained to act as service animals.

According to ShareAmerica, the U.S. Department of State’s platform for sharing American stories, there are approximately 500,000 service dogs in the United States. Some of the dogs’ tasks can include guiding people with visual impairments, signaling certain sounds for those who are deaf, retrieving items for people with mobility issues and alerting about possible cardiac episodes or seizures.

20 THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022

CAMPUS

Illustrations by Katie Preston & photos by Sarah Frosch

Training dogs to perform such tasks takes a generous amount of time and effort, but some students at Miami University have made the commitment through an orga nization called Paws for a Cause Miami. Members of Paws for a Cause Miami help raise and train service dogs while on campus. Through this experience, these dogs are given the opportunity to learn how to support someone.

There are many service dogs in training (SDIT) on Miami’s campus who will hopefully go on to improve someone’s quality of life. Before the dogs go to their forever homes, the SDITs also provide many of their student handlers with someone to play with after a long day of classes and exams. Student handlers, like senior zoology, neuroscience and Spanish triple major Cassidy Waldrep, are often recognized around campus because of their SDIT.

In addition to co-fostering a 6-month-old English cream golden retriever named Palmer, Waldrep is also the secre tary for Miami’s chapter of Paws for a Cause. The organiza tion’s goals include educating Miami students about SDITs and training these dogs to the best of their abilities.

“Even though it might look from the outside that we’re just a club that lets you take a dog to class, that’s not even close to the goals of our organization,” Waldrep said. “Yes, our members do love dogs, but they also are passionate about helping others and raising awareness for the service dog community.”

Paws for a Cause Miami is always actively fundraising. The money is used to pay for monthly socialization ac tivities for their dogs, which include trips around Oxford and larger outings, such as visiting the Cincinnati Zoo and Newport Aquarium. Fundraising money is also spent on additions to the service dog park behind Cook Field and general philanthropy surrounding SDITs. Waldrep estimated that the organization has about 300 people and 14 dogs on campus.

TO CHANGE THE LIVES OF THE FAMILIES THEY ARE PLACED WITH.”

“THESE DOGS WILL GO ON

Jessica Schmitz, a sophomore primary education major, fosters a one-year-old goldendoodle named Apoc. Schmitz was introduced to Apoc during her first year through Paws for a Cause Miami, where she would often help take care of him throughout the day. Miami has a rule that service dogs in training are not allowed to enter the dorms, so she could not take Apoc full-time until winter break came along and she returned home. Once she did, their relationship flourished, and Schmitz has been training Apoc ever since.

Schmitz said that a college campus is a great environ ment to work with an SDIT.

“There isn’t anything specific about being on a col lege campus that causes [an SDIT] to fail, and I'd even say that being on a college campus gives them a better chance, as they are constantly being socialized and going to classes, dining halls, etc.,” Schmitz said.

Schmitz’s professors have also been more than wel coming about having an SDIT in class. Paws for a Cause Miami members always email their professors before the semester starts to ask permission to bring a dog to class.

“We will honor their wishes if they don’t want the dog to come to their class,” Schmitz said. “But in my experience, professors have always been super excited about the possibility of an SDIT coming to their class.”

Because being an SDIT handler is a lot of responsibility, it takes students some time to become full-on trainers for Paws for a Cause Miami.

First, students must apply through a parent organiza tion; the most commonly used one is 4 Paws for Ability. Questions on the application normally ask about previous experiences with animals, why the applicant is interested, and how much time they have to commit to a dog.

Next, students must complete a Miami Canvas course wherein they learn about training and how to socialize the dogs. Students then have to attend either a Zoom class or in-person training that further emphasizes what handlers need to know.

When things get difficult, handlers try to remember what motivated them to start working with an SDIT. Schmitz is inspired to keep working with SDITs because she loves seeing them succeed and get placed with a forev er owner.

“These dogs will go on to change the lives of the families they are placed with and will allow their child to have a new sense of independence,” Schmitz said.

Kennedy Miller, a senior organizational leadership major, helped train a Newfoundland golden retriever mix named Kustard from 10 weeks to 16 months old. Miller said there are negatives and positives of having an SDIT on campus.

THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022 23

“It takes so much time,” Miller said. “Everywhere you go, your dog goes too. Sometimes you have to miss things that are a part of the ‘college experience.’”

These students are constantly responsible for the care of their dogs. Leaving them for hours isn’t a choice, and not everywhere accommodates them.

Some typical college scenes, such as bars and parties, aren’t appropriate for these dogs because it’s loud and students try to pet them. If handlers can’t find someone to help watch their SDIT, they may have to miss out.

For this reason, Miller says it's essential for fellow SDIT handlers to lean on each other for support and guidance throughout the process.

“It is comparable to being a single parent trying to juggle having a child and doing well in college,” Miller said. “It can suck, but it’s worth it in the end. Another challenge would be that you put your entire heart into this pup and have to give him up in the end.”

Both strangers and friends often commend Miller for all the time and effort she puts into Paws for a Cause Mi ami because she brings awareness to the need for service dogs.

“The biggest benefit is the final product, which is the moment the child first lays eyes on their forever dog, and the little wins each family has because that dog is success fully doing his job,” Miller said.

Another Paws for a Cause Miami member, junior criminal justice major Bry Schleifer, said every day with an SDIT is different. Schleifer is currently training a one-year-old purebred labrador named Zach. Schleifer originally became involved with training service dogs during her junior year of high school.

“Being involved has been life-changing,” Schleifer said. “It has brought me close with so many people of all ages and [has given] me a community and purpose in high school. When I saw that I could continue in college, I knew I had to because it was my life in high school and I was not ready to part with it.”

Zach enjoys sleep and usually lets Schleifer sleep until 9:30 a.m. Depending on the day, he will go outside before or after breakfast, which is served when he wakes up. Zach doesn’t have a designated lunchtime and is fed training treats throughout the day.

Schleifer doesn’t bring him to class if there is a lab activity or on exam days because Zach tends to get fussy. When Zach does become fidgety, she will give him a bone or get up and exit class to give him a chance to move. Luckily, Schleifer’s professors love her SDIT; one even gives him a treat every day before class.

John Jeep, a professor of German and linguistics at Miami, enjoyed having an SDIT in his classroom.

“In a German class, the student had a dog in training,” Jeep said. “It was a welcome diversion for the students, but there was a restriction on petting as part of the train ing regime.”

No matter where SDIT handlers go, whether in class or to a restaurant, they often deal with people wanting to pet their dog unexpectedly.

Students should always ask handlers before petting, offering treats, or approaching an SDIT.

“Zach is still very excitable, so having people random ly come up and pet him while he is working is extremely distracting to him,” Schleifer said. “We also face many challenges because not many students know what our organization is and don’t always respect our boundaries with our dogs.”

Schleifer also stressed the importance of remember ing that SDITs are far from perfect because they are still animals.

“You won’t meet a puppy raiser who hasn’t cried because of their dog, who hasn’t joked about returning them,” Schleifer said. “Raising a dog is exhausting, but it is worth every second of it when you see someone get their eyes back.” S

THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022 25

Vignettes

/vin.yets/ plural noun

A collection of brief stories that provide a glimpse into the lives of five different students.

28 THE

STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022

MIAMI

VIGNETTES

Illustrations by Macey Chamberlin

Riley Peters

I’m over the sink with a sponge in my hand doing my least favorite chore.

I’ve always hated doing the dishes — wet food left on the plates, milk rotting in cereal bowls.

My mother actually enjoys it. She says it’s “calming.”

That never made sense to me.

I always thought that when I liked to do the dishes I’d start to become a grown-up.

I last saw my parents when they helped move me into my very first house. My name was on the lease. I made the rules. I had the code to the front door. From the outside, I looked like a true grown-up.

But I felt like an imposter. Like I was living in someone else’s house who would soon come home and hopefully take care of everything.

A call to my mother: “How should I wash a comforter?”

A call to my father: “My car is making a funny noise.”

A call to my mother: “How do I make a doctor’s appointment?”

A call to my father: “Can I have that one recipe?”

All of the unnoticed, unspoken things my parents did were now left to me. I was stuck in limbo — not yet a grown-up, but not a kid anymore.

I wondered when I’d finally become an adult and how I would know it had happened. It wasn’t until one day, months later, when I was washing the dishes and humming that I caught myself thinking …

“This is nice.”

A quiet transition into adulthood.

I was no longer stuck between adolescence and adult hood. No longer an imposter in someone else’s house.

Calls to my parents were now about the material of my classes, the jobs and internships I wanted, and my plans for the future.

And suddenly, quietly and peacefully, doing the dish es a few times a week didn’t seem so bad.

Dishes Building her Body

Evan Stefanik

Nickole Sandoval hurls a final rice cake wrapper into the trash can backstage before going on stage for her first bodybuilding competition.

In her dressing room mirror, she looks for proof of the only food she ate for half a year: ground turkey, egg whites and chicken salads. Her perseverance shows when she flexes.

An expensive tan from head to toe makes her shine like a bronze statue. She beams with the same pas sionate smile as her bodybuilding idols on Instagram. Nickole’s coach approaches and instructs her how to pose before adjusting her $450 bikini to fit tighter around her muscles.

Once her coach manipulates her posture and lets her relax, Nickole tries to stretch out any tension in the next-door gym space.

Although she is thick-legged from cardio and buff from lifting weights, she maintains a nationally-quali fying hourglass figure. She had to tone her body to the extreme for this competition and now survives at her leanest.

She used to face frequent near-paralysis on her couch, suffering intense physical fatigue from her con stant exercise. Training meant spending many of her nights rehydrating and staring at the ceiling instead of partying with friends.

As an educational psychology master’s student and lifelong athlete, Miami University’s recreation center has allowed Nickole to meet fellow bodybuilders who have encouraged her to compete.

When she feels ready, Nickole takes one triumphant breath, raises her chin, and steps onto the stage. Along the way, she catches a whiff of the uneaten box of do nuts that waits for her on the vanity.

THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022 29

“You know, the Puritans were pretty brutal,” he said as he looked up from a gray hardcover titled “New England Legends and Folklore” and uncrossed his legs.

You would instantly believe him if he said he was a direct descendant of the Puritans. His curly brown hair, his freckles and his skin — only slightly tanned because of a parks job he worked over the summer — say it all.

He was aware that he was descended from New En glanders, but there were so many things he didn’t know about his heritage until he researched with the help of Ancestry.com and Google.

He didn’t know that his ancestor from 11 genera tions back was the second wife of William Bradford. He didn’t know that three of his ancestors were signers of the Mayflower Compact. He didn’t know that his mom had known about his heritage for ages and had never bothered to tell him.

Back in Session

Lexi Whitehead

After building up a 4.3 GPA throughout his first three years in high school, Ryan Helms ended the first quarter of his senior year with a 0.6.

Ryan had been skipping school and not doing his work.

Having been accepted into the University of Ala bama with a full-ride scholarship, he saw no end-goal in continuing to try in school, so he started avoiding class and missing assignments.

Between six Advanced Placement classes, an after-school job and having to study what felt like a random spattering of subjects, Ryan didn't feel focused.

After years of being in his school’s gifted program, taking the highest-level classes and competing with his peers for the best grades, Ryan was burnt out and realized he no longer wanted to suffer for his grades.

Things got slightly better when he made it to college in 2014, but they still weren’t perfect. He was glad to take a more focused set of classes for his engineering major, but he couldn’t break the habit of skipping classes.

Shr-Hua Moore

He didn’t want to know about his father’s ancestors.

His dad left before he was born. However, he didn’t notice until he was six and realized that all his classmates had two parents instead of one. Besides a phone call every once in a while and a birthday present that’s always a few days late, his father is just another stranger.

While he isn’t mad at him anymore, he also isn’t eager to meet him.

“He’s just a person that I happen to share 50 percent of my DNA with,” he said, leaning back in his chair.

Maybe his obsession with the Puritans was a way to get out of doing his chemistry homework — or perhaps it was easier to learn about forefathers long gone rather than the father who had never been there for him in the first place.

Ryan spent three years at the University of Ala bama, then he took three years off to figure out what he wanted to do with his life. He spent his time working at a rock climbing center and thinking about what career would fit him best.

He thought about attending trade school during that time, but after people in trades dissuaded him, he decided to go back to college for a business degree.

He got a two-semester associate degree from Cincin nati State Technical and Community College, then he transferred to Miami University this year. He didn’t get into the Farmer School of Business like he wanted and is currently a University Studies major.

Although he isn’t in Farmer, he can still take busi ness classes and focus on reapplying.

The focus of his business classes and his choice of a thematic sequence in geography means he’s taking classes he likes. After almost 10 years, Ryan feels like he has an end-goal. Sometimes he still struggles to motivate himself to study, but day by day he’s working to build better academic habits.

Forefathers

30 THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022

Behind the Counter

Jake Ruffer

Students foraging for pretzels, Gatorade and ramen noodles wander into the Emporium market in Arm strong Student Center. They seize upon their finds then plunk them down onto the counter.

“Go ahead and tap whenever you’re ready,” the blonde girl working the register says.

The customers pay and walk their snacks out the door while she remains a cashier.

They won’t learn that she doesn’t really think of herself like that — she actually prefers stocking the

zoology and picked up a second major in environmental science. Her Spanish minor comes naturally.

On Saturday mornings, she gets up before 10:30 a.m. to help clean up trash around town with Zero Waste Ox ford. She plays guitar, swims breaststroke for Miami’s club Redfins and likes to watch anime.

She loves her mini labradoodle Cooper and her betta fish Bubbles. She says it’s always a good day if she’s seen some bugs. Sometimes her friends send her pictures of the insects they see on their walks to class to help her

The best day of her life was when she hiked up Ca dillac Mountain in Maine and watched the sun rise over the bay with her mom.

She says that the people she helps out at work can become like regulars, coming in during her shifts each week. And yet, with everything there is to know about Emily Davidson, many of them won’t even stop to learn her name. S

THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022 31

A Life Almost Taken, Mine Forever Changed

By GraciAnn Hicks

*Trigger Warning: Description of Violence, Mention of Anxiety, Depiction of Panic Attack

A red brick-paved path leads the way to the covered outdoor amphitheater where hundreds of people sat in anticipation of award-winning author Salman Rushdie’s lecture. On the way there, audience members could catch glimpses of Chautauqua Lake as they passed by well-maintained Victorian-style houses with lush flowers lining their perfectly decorated porches — porches that often hosted audience members animatedly discussing the events they attended that day.

With green Chautauqua Institution seat cushions in place, hearing aids adjusted and children or grandchil dren handed over to the boys’ and girls’ club, audience members could settle in to enjoy the 10:45 a.m. Friday lecture.

Rushdie and Henry Reese, founder of Pittsburgh’s City of Asylum, a non-profit organization supporting exiled writers, were introduced to the audience. Before Reese could begin the interview, a man from the audi ence rushed on stage.

While those sitting higher up in the amphitheater couldn't see what had happened, those who sat closer could see the man pummeling Rushdie.

Police detained the attacker. Rushdie lay on his back, blood pooling under his head. News that something terri ble had happened began to spread through the grounds.

Meanwhile, I was a few buildings over, sitting at my desk in the newsroom of The Chautauquan Daily, the newspaper that serves the Institution. A photographer entered the newsroom and announced to the group that someone had attacked the morning lecturer. Things like this didn’t happen at Chautauqua.

THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022 37

Processing the trauma caused by an attempted murder at my place of work

PERSONAL HISTORY

Illustrations by Erin Morgan

I looked up, and suddenly they were rushing for the door. It was only then that I heard why the photographer had returned: Someone had rushed on stage during the lecture with Rushdie. I quickly joined a group of interns

The amphitheater was a two-minute walk from the newsroom. We made it in maybe 30 seconds and saw hundreds of people spilling onto Bestor Plaza, frightened and crying. For 150 years, children had laughed and played on the plaza; musicians had performed here, and people had lingered to discuss the lectures they'd just

As I took in the scene, it began to sink in that some thing terrible had happened. The amphitheater was blocked off with police tape when we reached it. As we stood around trying to find more information, we saw our Editor-In-Chief, Sara Toth, sprinting across the plaza

More than a dozen of us followed her and crowded onto the porch of the office. Sara had her signature coffee in one hand and a cigarette in the other by the time we caught up. We stood in silence, awaiting her guidance.

is not an average newspaper. It’s owned by the Chautauqua Institution; it’s a house organ. In the off-season, Sara and her husband Dave Munch, who acts as photo editor for the paper during the

Sara was candid with us, sharing that she was strug gling against two different instincts. As a reporter, she wanted to tell us to get after the story as soon as possible. As an employee, she didn’t know what was safe or what

As we talked on the porch, Sara confirmed that Rush

Sara told us we could always report on the community reaction later. At this point, the Institution was under lockdown, and she wanted us inside the office. During this conversation, the first outside news report poured in from Associated Press. A writer happened to be in the audience, not even to cover the event, and less than 15 minutes after the amphitheater was evacuated, they

38 THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, SPRING 2022

The air on the porch was heavy with defeat. For another news source to report on the story first felt like failing as journalists.

We accepted what Sara said and spilled back into the office. I sat at my desk in “editors’ island” and tried to return to my work. I didn’t get far before I began writing a reflection on the day to process and record my experi ence. I only wrote 98 words before more updates came in from another photographer.

He had also been covering the event and had charged the stage as soon as the man attacked Rushdie. A group of interns crowded around a computer to look at his pictures.

I hesitated. Then I eventually went over to look for myself. I had seen powerful photos before, including several that showed war refugees and national crises, but I had never been so close to a tragedy, then viewed it through a camera lens.

In the pictures, I saw blood spilled around Rushdie’s body, confirming our fears that he had been stabbed.

The attacker had brought a knife into the amphithe ater and tried to kill an internationally renowned author in front of an audience of hundreds of people.

I couldn’t look at the pictures for very long.

Because the photographer was a Chautauqua em ployee, the Institution technically owned the pictures. He couldn’t send them to major news sources until he had Chautauqua’s OK. If he’d had permission, his pictures likely would have been on the front page of The New York Times the next day. He might have even won awards for them. But all he could do was stare at the screen.

I became overwhelmed with feelings of uselessness, and I asked the other intern from Miami University, Skyler Black, to talk with me outside.

We both felt that as journalists we should do some thing. We could not accept sitting in the office while a tragedy that was making international news unfolded in our place of work. Still, we didn’t know what would get us in trouble.

We also didn’t know if we would be safe to report. I worried that the man who attacked Rushdie might not have been working alone.

As we stood outside the office, Arden sprinted toward us.

“My mom just called and told me the Everett Jewish Life Center is on fire!”

I froze. Reporters and photographers began to run toward the building, one of the many religious spaces on campus.

If it was on fire, then this was a calculated attack on all of Chautauqua, which prided itself on being an interfaith safe haven. I was afraid and stayed back in the news room. I once again felt as if I were failing as a journalist, and I reasoned with myself that others could get the details.

I called my dad. I had been texting my mom and dad updates the whole time, but I couldn’t tell them over text that there was possibly a literal terrorist attack happen ing where I worked. Shortly after I got off the phone with him, the interns returned to the office. The “fire” was a false alarm.

What terrible timing.

After confirming that the Institution wasn’t under attack, I returned to my conversation with Skyler, and a few others joined us. We all agreed that waiting around wasn’t an option, but we didn’t know where Sara was, as she had been running around trying to find more information.

THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, SPRING 2022 39

“I just don’t know how someone

I decided to take charge. We walked back into the office, and I approached Dave.

“I’m going to level with you, Dave,” I said. “You have a room filled with journalists who want to report on this story.”

He seemed flustered and scared, but I pushed him because we felt we had a duty to fulfill.

“I don’t want my wife to get fired. I don’t want to get fired,” he said as concern wrinkled his eyebrows.

I assured him that we didn’t want that either and asked if he knew what we could do. He eventually con ceded and said we could go talk to people but not bother them too much.

So, we headed out to report on the community's reaction as a team. We passed the main entrance to the grounds; the line of cars trying to leave and return was longer than we had ever seen. The Institution had been on lockdown, but it now allowed people to enter and exit.

Vans with reporters were already positioned outside the gates. I felt disgusted that they could bother a com munity processing trauma, even as we were about to do the same thing.

As we walked through the grounds, talking with employees and residents, the scene felt apocalyptic. The roads were normally filled with people on their way to events, leisurely strolling as grandkids rode ahead on bikes and their dogs stopped for bathroom breaks. That day, the roads were empty, except for several visitors walking or driving toward an exit with suitcases in tow, with no intention of returning to Chautauqua.

Meanwhile, the art vendors who occupied Bestor Plaza every Friday sold their products as usual.

“I don’t understand how they can act like nothing happened,” Skyler said angrily.

After talking to people milling about the plaza, we re turned to the office and were instructed to put everything we had gathered from reporting into a shared document. Sara told us that we would not publish a news story about it until the following day, when it would appear in the weekend paper. The Chautauquan Daily is foremost a print publication with a mostly graying or grayed audi ence, so articles are never published exclusively online.

Instead of returning to editing, I began searching through our massive bound archive with all newspapers from the summer of 2010 when Rushdie had visited Chautauqua before. I eventually found an article that Sara had written when she was an intern.

In 1989, Iran’s leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, issued a fatwa, which is a legal ruling from an Islamic leader, that called for Rushdie’s death. This fatwa result ed in previous attempts to assassinate the author. Mere months later, though, the Ayatollah died.

During his first lecture at Chautauqua, Rushdie had been asked about the fatwa, and he responded: “One of us is dead. … You know what they say about the pen being mightier than the sword? Do not mess with novelists.”

Though Rushdie’s own life had been at risk, he felt confident enough in 2010 to boast of his own survival over the Ayatollah’s. According to Sara’s article, he made this statement on the very stage where an attacker had tried to kill him today.

My chest sank under the horrible irony.

Around dinner time, we ordered food from a local pizza place, which was a Friday tradition, but the tradi tion felt stale. Most of us didn’t have much appetite even though we hadn’t eaten in hours. The food didn’t offer the normal chance for casual lunchtime conversations; it was purely fuel to keep us moving forward. I placed over half of my wings into our shared newsroom fridge and returned to work.

40 THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022

could do something like this.”

After editing the remaining pieces for the weekend paper, I left twelve hours after I arrived. Twelve-hour days weren’t uncommon for a copy editor, but that day felt infinitely longer.

I returned to the house I shared with six other interns. With heavy footsteps, I climbed the stairs, walked into my shared bedroom and burst into tears, feeling thankful my roommate wasn’t there.

It was a primal release of emotions that had been building the entire day. I hadn’t properly processed any of the shock, hurt or anger that a man being stabbed at your place of work brings.

I called my mom and talked through my feelings. While on the phone, I received an invitation from girls in the other intern house to come over and drink. I didn’t think it would be a wise decision for me. I told my mom, and she agreed and told me to go to bed.

The moment the call ended, I contemplated going to sleep. I truly felt as if I had been awake for 24 hours. I knew it would be a bad decision to go, but my friends — the only other people who had experienced the day’s events as staff of The Chautauquan Daily — wanted me to come.

So I drove to the other interns’ house anyway because I didn’t want my last memories with my co-workers to be of us scrambling about the grounds to report on a trage dy. I didn’t want my bittersweet goodbye stolen from me.

When I arrived at the other house, people were party ing as if nothing had happened. There were four strang ers there: out-of-town friends of one of the designers who had planned to visit that day. They hadn’t worked at Chautauqua the whole summer. They didn’t under stand what an event like the stabbing meant for a place like that, or what it meant for us. They just wanted to get drunk with their friend.

So I tried to join them. If everyone else could have fun, I thought I could as well.

I don’t remember the exact moment things changed, but one moment we were laughing, the music was blaring and I was enjoying myself, and then I was in a friend’s bed having a panic attack.

As I lay under her quilt, a tsunami of tears flooded from my eyes, and my shallow breathing came fast.

I was inconsolable. I kept repeating, “I just don’t know how someone could do something like this.”

Skyler and some of her roommates tried to comfort me, to calm me down. They did everything they could imagine from having me talk to a crisis hotline to calling my mom at 3 a.m. I’d have moments where my breathing would slow enough for me to croak out a few sentences, but I couldn’t stop hyperventilating.

While I shattered under the pressures of the day, people continued to party out in another room. I felt like an embarrassment: a pitiful story they would tell their real friends when they returned to their university in a few days.

I reassured them I was fine and tried to sleep as they returned to the party. But I couldn’t shake the panic attack; it was unlike any I’d had before, which usually didn’t last longer than 20 minutes.

It was one thing to read about terrible, violent events in the news, but to have one happen in such close proximity, in my place of work where parents had never before worried about letting their children walk around or ride bikes alone and where they thought nothing bad could happen — it wrecked me.

I have always been an idealist in denial. I’ll say that I’m a realist, but it always broke my heart to expect any thing other than good from people. It wasn’t that I had never dealt with terrible people or been hurt badly; I just needed to remain optimistic because the alternative left me unable to function. My worldview had been shattered, though. If someone could try to kill somebody they didn’t know in front of hundreds of other strangers, maybe people aren’t generally good.

As I wept, I felt every ounce of idealism exit my body.

After three hours of what felt like fighting for my life, I screamed out for help, but nobody couldn’t hear me over the music. Since my friends had left me, I had become convinced that I would die.

The worry that I would die was a sick psychological trick my brain was playing on me, compounded by my fears, a shortage of oxygen and an abundance of alcohol in my blood.

Eventually, my friends returned, and I conveyed my concerns to them. They tried to convince me that I didn’t need to go to a hospital and talked me out of calling an ambulance. However, I couldn’t be bargained with.

Before we walked out to the car, they cleared the kitchen of the partiers and helped me put on my shoes while I kept my head down sheepishly.

A friend who hadn’t had a drink in hours drove me to the local emergency room. They gave me anxiety pills, Vistaril. I began to calm down, and at about 5 a.m. I went home.

The following day, all I did was lay in bed, hardly mov ing or eating, and I kept checking all the news sources.

I had to go into the office on Sunday like normal to edit articles for Monday’s paper, and I was supposed to leave Monday, so I thought about not going in at all. I couldn’t fathom walking back onto the Institution's grounds. I joked about getting to the entrance and break ing down, but I really thought it was a possibility.

I forced myself to go anyway because the other copy editor was out of town, and I couldn’t let Sara edit the paper alone.

Sunday was another 10-plus hour day. The office was mostly empty except for a couple designers, Sara and myself. I asked one of the designers what her favorite Disney movie was and proceeded to put on “Tangled” while we worked.

We needed the comfort of something that brought us joy as children. We needed to be reminded of a time when nothing like this could happen to us.

I left on Monday as planned and returned home with only four full days until I would move into the house I would live in during my junior year at Miami.

I wanted to hide from the world. I didn’t want to return as a broken person to my Miami friends who I hadn’t seen in months. I was damaged, and it wasn’t their problem. I already felt like I had burdened my fellow interns and my parents enough with my grief.

I felt weak. Stupid. Pathetic.

Nobody else broke down the way I did.

People told me that everybody processes things differ ently, but I couldn’t believe it.

Before leaving for Miami, my mom and I went to Walmart to purchase a few last-minute items. As we walked through the store, I felt more anxious than ever in public. It was a busy place filled with strangers who might do anything.

I felt completely out of control, just like I was at Chautauqua — like anyone could hurt me and there was nothing I could do about it.

I have always struggled with control but seeing how very little I actually had made me feel unsafe going to places that normally wouldn’t be a problem.

42 THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022

I talked with a pastor from my home church, and I cried. A lot. I left feeling a little lighter, but I still felt as if nobody understood exactly what I was going through.

I didn’t understand it myself. I wasn’t attacked. I wasn’t even in the amphitheater when it happened. Yet I was entirely robbed of any sense of security I felt in completing day-to-day tasks.

I understand now that my reaction was valid. But I will never understand how people are capable of such evil. I still carry the trauma with me in unexpected ways, like when I drove to Columbus, Ohio, for fall break and saw that a car had flipped over the median and was upside down.

As I drove past it, my eyes welled with tears. I didn’t know those people and couldn’t see any blood. Yet anx iety crept in. Pressure built in my chest, and my knuck les turned bright white as I gripped the steering wheel harder.

That could have been me. That could have been any one I knew.

Weeks after I drove past the crash, while I was on a phone call with my mom, she told me that my aunt and cousin had been in a bad car accident. Both situations only reaffirmed what the attempted Rushdie murder has taught me: We have no control over the bad things in life. I’m still in the process of mourning this fact.

I’ll likely always carry the trauma, but I’m moving forward. S

THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022 43

Time to BeReal

A look into the trendiest new app and the pressures users face on social media

By Megan Miske

By Megan Miske

Almost every social media platform allows the same affordances to users when they post a picture: They can choose exactly which image to post, edit it and apply filters before selecting the perfect time to make it public.

These platforms, like Instagram, allow for users to build their follower base into the millions, become influencers and post content for anyone to see. However, a new social media app was recently developed with the promise of doing something completely different.

“Time to BeReal: 2 mins left to capture a BeReal and see what your friends are up to!” the app chimes.

BeReal is a social media platform where once a day at a random time every user is prompted to take a picture using their front and back camera within a two minute window of time. The app was founded in 2020 and is currently number one on the Apple app store charts for social networking. With no filters and no editing allowed, the concept is simple: Take a picture wherever you are,

Madison Rickabaugh, a junior middle childhood education major, said she has enjoyed using the app so far. She uses social media, like BeReal, to stay connected with her friends that she doesn’t see very often.

“I think it’s a really cool concept,” Rickabaugh said. “It doesn’t show [just] the highlights, it shows people’s daily, realistic life.”

Rickbaugh still uses Instagram despite disliking ele ments of the social media platform. She believes that the tradition of people only posting when they look good or are doing something fun needs to change. She also thinks that users need to take more responsibility when it comes to posting realistic pictures of themselves.

“I think at one point in my life, [Instagram] did have a negative impact [on me],” Rickabaugh said. “I follow a lot of mental health accounts now, and I make it more about seeing my friends.”

Before she changed the way she used Instagram, Rickbaugh felt like people only painted themselves in a positive light online, and it often made her feel insecure.

46 THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022

TRENDING

Illustrations by Hannah Potts

Evidence of people wanting a more authentic social media platform started in July 2022 after a petition called Make Instagram Instagram Again started circu lating the Internet. The petition, created by influencer Tati Bruening, encouraged Instagram to go back to the basics of being just a photo sharing app that is used among friends.

As the petition gained attention, it was reposted by celebrities like Kylie Jenner. Today, it has over 300,000 signatures.

“There’s no need to overcomplicate things, we just want to see when our friends post,” Bruening wrote in the petition. “The beauty of Instagram was that it was INSTANTaneous.”

Andrew Peck, an assistant professor of strategic com munications at Miami University, said the creation of a seemingly more authentic platform was a good business move for BeReal.

“[Users] are fed up with how inauthentic, polished and filtered Instagram has become,” Peck said. “[BeReal] feels authentic and a little bit free of corporate influence.”

While BeReal seems trendy and different right now, Peck thinks it is difficult for social media apps to remain authentic and cool. As he put it, social media companies have to constantly keep running to keep up with the interest and demands of their audiences.

“The concept of coolness is a moving target,” Peck said. “Once something becomes mainstream and there are more ads, [the app] becomes less cool.”

Despite BeReal’s popularity, some social media users like Bayley Gilligan, a senior strategic communications major at Miami, have not downloaded the app.

Gilligan said he hasn't downloaded BeReal because he feels it infringes on his privacy, and it doesn’t seem like the app is as authentic and earth-shattering as it is made out to be.

“I thought the app was a lot more close-knit, but I’ve noticed how many people that my friends have added on the app,” Gilligan said. “I personally don’t care to see what everyone is doing and how that compares to my life at that moment.”

Gilligan is still on other social platforms like Instagram and Twitter. While Gilligan said he doesn’t feel a lot of pressure to download the app, he does occasionally feel left out when the BeReal notification goes off everyday.

“As soon as I came back to Oxford this fall, I imme diately noticed that most of my friends had BeReal,” Gilligan said. “One of my roommates will say ‘Time to BeReal,’ and they will stop what they are doing to take the picture.”

The concept of the app going off once a day, causing some people to stop what they’re doing, has become the butt of many jokes. A recent Saturday Night Live skit even joked that someone would stop in the middle of a bank robbery if their BeReal notification were to go off.

Ron Becker, a professor of media and communi cation at Miami, agreed with some of the sentiments shared by Gilligan. It wasn’t shocking to him that people have begun to want a more authentic social media experience, but he wouldn’t say that BeReal is authentic, because he thinks people will always find a way to filter and frame their life.

THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, SPRING 2022 47

It shows you that every day is something special.

Even though the picture was taken a few months ago, it really makes you wonder where all the time went.

“The camera itself is offering a version of a repre sentation of your reality that is not the same as your authentic complex life,” Becker said. “Even if you're walking around and you're taking a photo when BeReal tells you, it's only capturing part of the environment that you're in at that moment. It's only probably capturing part of your clothing. It’s only getting one angle of you.”

Because BeReal has features that show other users how many times someone retook their daily picture and how late after the two-minute time frame they posted it, Becker also finds BeReal to be intrusive.

“If the app works to make us respond to it when ever it signals to us to do something, that is a unique authority that is more intrusive than Instagram would be,” Becker said.

Despite these beliefs, Becker believes that there are pros to BeReal, like that it draws more attention to the fact that other social media apps encourage people to present a curated version of themselves. He said, how ever, that there is no foolproof way to stop people from curating their lives.

“If you still want to look like you're having an exciting life, if that is really important to you and you're using BeReal, that could create a perverse incentive to con stantly be having a good life,” Becker said. “That is an amazingly intrusive and manipulative aspect of it.”

Considering the app is only two years old and newer still to most users, some people like Hannah Lewis, a senior strategic communications and arts management double major, wonder if BeReal will be able to stick to its original mission and values.

“I’m curious to see if BeReal will conform to other social media platforms, like if you are able to post videos or repost someone else’s BeReal,” Lewis said.

Something that Lewis has enjoyed about the app is the ability to privately view her old BeReals. She compared the concept of BeReal to a video she saw on Facebook where a man took a picture of himself every day for seven years. At the end, he had a picture archive of a significant part of his life.

“It shows you that every day is something special,” Lewis said. “Even though the picture was taken a few months ago, it really makes you wonder where all the time went.”

Regardless of whether or not BeReal is accom plishing its mission of authenticity, it is making waves throughout the world of social media.

TikTok recently introduced a feature called TikTok Now that imitates the concept of BeReal, but with video. According to the platform’s website, TikTok Now allows users to capture a short 10-second video or static photo once a day, simultaneously with other users, and share it with their friends.

As the concept continues to grow and change, and some users continue to gravitate toward a more authen tic social media landscape, people will have to wait and see if BeReal has the answers they are looking for. S

Dancing with the Second AmendmentMY PARADOXICAL EXPERIENCE AS A FIRST-TIME GUN BUYER

By Devin Ankeney

It was a regular Thursday. I had two journalism classes, got some homework done and enjoyed the sunny, breezy, cool-but-not-cold weather. When my last class of the day ended, I hurried out the door at the first moment I could. Not two hours later, I found myself holding a Hatfield SGL .20-Gauge Break-Open Shotgun. ***

I’ve seen the same headlines many people have: the same number of children dead, the same number of mass shootings and the same number of proposed bills in any given state to combat or promote gun ownership.

But, like most of those who have spent their entire life on the left side of the political spectrum and in disagreement with the common interpretation of the Second Amendment, I had never held a gun before. I’d only ever seen one, strapped to the waist of a cop or in between the front seats of a police car.

After many years of understanding politics and spending time in New York and Ohio, my stance on gun laws was neither set in stone nor comprehensive. I cer tainly think gun usage is out of hand and that there are far too many guns in this country, but I can’t say I know exactly what should be done about it.

What I do know is that I'd be talking out of my ass until I found out more about it. I had to admit I was curious, even though I didn't want to own a gun, load one, or shoot one. But I did start wondering: What exactly is it like to go out and buy one? Is it really as easy as I’d heard? Is there some higher power, some hidden enlightenment, that comes from the possession of a firearm?

I yearned to know what it was about these con glomerates of plastic, wood and metal that drew people in, that made them so passionate about being legally allowed to possess either one or 30. It’d always felt like an “Us vs. Them,” an anti-gun vs. pro-gun culture, but I wondered if it had to be that way. So, I embarked on a journey to understand gun owners.

Maybe it was the snowflake in me, or maybe it was the fact that I’m only 20 years old, but it terrified me: To go into a gun store, point, and say, “that one, please!” was a painful thought. It felt like a complete bastardiza tion of the self in one fell swoop.

I couldn’t shake the memory of learning about Sandy Hook, Parkland or Las Vegas.

I didn’t know where to look for a gun. I figured most people started out the same way: by looking up “guns” and checking out the nearest places. So I did the same. I was scared of setting foot in what I imagined in my head as the temple of doom.

With that in mind, I knew I had to dangle my feet in the water first. I needed to know the type of places I was dealing with before actually picking the one where I would make my ultimate purchase.

I started with a pawn shop in Richmond, Indiana. Thought I’d give it a shot. It’s 45 minutes down the road anyway.

I pulled up to what looked like it used to be a corner 7/11 in the small, poor city.

50 THE MIAMI STUDENT MAGAZINE, FALL 2022

***

EXPERIENCE

Illustrations by Caitlin Dominski

“‘If you voted for and continue to support and stand behind the worthless, inept and corrupt administration currently inhabiting the White House that is complicit in the death of our service men and women in Afghani stan, please take your business elsewhere.’

blunt notice”

The sign outside made me twitchy. By no means am I a fan of “He Who Steers the Ship at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue,” nor can I say I’ve been a fan of any of the fine gentlemen in office before him. I did, however, vote for the guy they were referencing in the window, and I needed to try to be inconspicuous and fit in.

A younger woman with dark hair and various pierc ings, along with a salesperson's attitude, greeted me as I walked in.

I let out a meager “Hi,” like a small cat in a Disney film, before wandering around the store and looking at the video games like a dork to make up for it.

After a minute or so, I made my way back to the wide, glass-case counter filled with every weapon of which someone could dream. I started with the knives and switches, easing myself in. But then I turned and looked at the dozens of dark, metal weaponry placed on the wall behind the counter, trying to make out the prices to see what I could afford.

I asked the saleswoman to see a couple.

“New York! You wouldn’t be able to buy this any way,” she said after checking my I.D.

I might as well have been wearing a shirt that read: “First-Time Buyer, Lifetime Moron.” I guess the first shop is going to go down in my personal history as a learning experience. ***

It’d been a week since I first tried to buy a gun, and I couldn’t shake the thought of it. I kept thinking about holding one of those deadly masterpieces in my hands, about knowing what it was like despite the intense fear the image brought to mind.

I gathered my personal documents, ran out of my class that ended at 4:10 p.m. and bounded southeast to the Hamilton BMV in my silver Subaru hatchback, which is decorated in West Wing, Human Rights Cam paign and Save Our VA bumper stickers. I had to get there with enough time to get my Ohio license before they closed at 5 p.m.

I was out by 4:58 p.m., temporary license in-hand. Success.

A few miles further west, I headed down the heavily-trafficked Route 177 until I saw the small, tree-covered front of the shop and its large overhead sign: “GUNS.” It was only 25 minutes from “the most beautiful campus ever there was.”

I learned later that what I knew as “GUNS” was ac tually the Southern Ohio Gold & Silver Exchange, a title hidden by a tree.

I turned into the parking lot, my heart beating fast like I’d ran there.

After a minute, I took a deep breath, stepped out of my car and made my way to the front door. There was an intimidating warning in the window that the store is not responsible for customers’ safety once inside.

Upon entry, I was confronted with the dense air that only comes from decades of smoking indoors and a room with an intensely saturated, maroon carpet. I was instantly reminded of my grandparents' house where it felt like sucking on a straw to breathe in their dank living room.

The familiar jingle of the unfamiliar door rang as I let it swing behind me.

“How ya doin?”

I was greeted by only the distant voice of a mid dle-aged man whom I couldn’t see.

The voice came from an office behind the checkout counter, where I presumed the shopkeeper planted himself when the shop was empty.

I took a few more steps in, seeing a line of guitars and amps along the wall to my right, and various piles and racks of power tools to my left. Inside the glass counter by the checkout were various jewelry items one would find at any pawn shop in the country.

Ahead and to the left were what seemed to me like hundreds of guns. Long guns on the left, vests and other equipment dead ahead, and handguns to my right.

As I looked around the corner, trying to see where he was, I told the well-hidden man I wanted to take a look at the long guns. He reminded me to prompt him with any questions I might have.

Because I was only 20 years, I couldn’t buy a hand gun in Ohio. Only the long guns: rifles.

I walked over to this part of the counter, where I saw a bright yellow sign shaped like “POW!” in a ’50s Batman flick, letting customers know it’s perfectly OK to walk behind the counter to look at the assortment of weaponry.

I made my way around the counter. I was once someone who never wanted to see a gun in their life, but I was now standing not two feet from dozens and dozens of rifles and shotguns.

After a few moments of browsing like it was a J. Crew store, I asked — who I had now assumed to be a hermit — to show me a few.