7 minute read

Alumni Profile: Dr. Tom Lovejoy '59

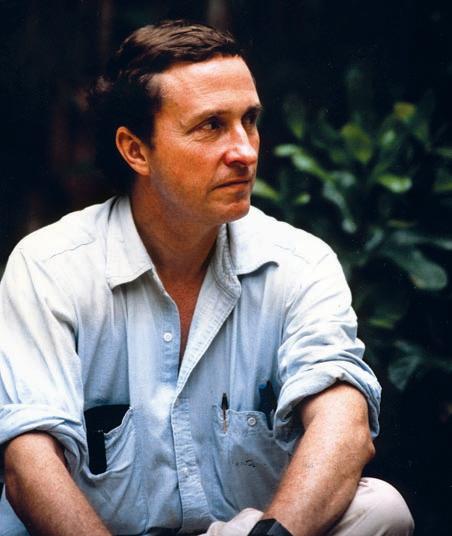

Tom Lovejoy ’59

Deep Green: the Life of a Conservation Biologist

Millbrook was the first boarding school that Tom Lovejoy visited in the fall of his 8th grade year. He saw the zoo and right then and there knew that Millbrook was where he wanted to be.

When Tom arrived as a III former in 1955, he instantly became entwined with a powerful, passionate, and inspiring teacher in Frank Trevor. He was not prepared for the impact Mr. Trevor would actually have on him in the classroom, but after only three weeks of school, Tom knew he was going to be a biologist.

After Millbrook launched Tom in 1959, he went on to earn his B.S. and Ph.D in biology from Yale. While volunteering in the bird division at the Peabody Museum, Tom connected with Phil Humphrey, a curator of vertebrate zoology at the Smithsonian, and eventually traveled with him to the Amazon in 1965, with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation, to begin work on his PhD. That is how Tom got started in the Amazon at a time when there was one road, three million people, and about two other biologists working there.

And so, did I think at the time I was doing my PhD or when I was a student at Millbrook that I’d be doing the kinds of things I’m doing today. Of course not. But I’m so grateful for the background because that’s what put me in a position to make a difference.

1970s, Tom in the Amazon

Dr. Lovejoy is now an internationally recognized champion for the conservation of biological diversity—also commonly referred to as biodiversity, a term he is credited with establishing in 1980. Tom’s career has been rooted in public service and is considered a model for scientists interested in translating biological research into environmental conservation. Tom conceived and designed the enormous ecological experiment in Brazil known as the Minimum Critical Size of Ecosystems, the largest experiment in landscape ecology. It looks at what happens when you break up a forest into fragments—and which is better, one big protected area or many small ones that add up to the same size. This study offered a large-scale perspective on the ecology of the tropics that had not been considered previously. As a result of Tom’s work, the world was alerted to the problems of tropical deforestation, the special demands on tropical conservation, and the importance of Amazonia as a cradle of biodiversity. Even now, Tom is always on his way to Brazil, as his research program continues in its 35th year. As he says, “My heart beats according to the samba.”

In 1973 Tom joined The World Wildlife Fund to manage their conservation grants, and he was swept up in the challenge of making positive changes in international conservation of the environment. As executive vice president, he helped the WWF grow into a global network in most European countries, Australia and Brazil, with affiliates in other countries. If he was not already busy enough, in 1982 Tom co-founded the public television series Nature and served as its principal advisor for many years. In 1987 he was appointed assistant secretary for environmental and external affairs at the Smithsonian, and in 1988 Capitol Hill discovered there was an official at the Smithsonian who knew about the environment. By January of 1989, Tom was taking Al Gore, Tim Worth, John Heinz and Ben Bradley (who was then executive editor the Washington Post) down to the Amazon and working with the Brazilians to see if there was something the U.S. could do to make a difference about deforestation in the Amazon. He then served on the first President Bush’s Council of Advisors in Science and Technology, where they talked about topics like climate change very early on.

In 1993 the U.S. Secretary of the Interior appointed Tom as his science advisor, and one year later he served as scientific advisor to the executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme, a position he held through 1997. In 1998 he became chief biodiversity advisor for the World Bank before joining the Heinz Center for Science, Economics and the Environment, an environmental policy think tank whose most important contributions have been two lengthy reports on the state of the nation’s ecosystems, the second of which was published in 2008.

1990s, Tom at Camp 41 in Brazil

Living on the interface of science and public policy, Tom remains the biodiversity chair and keeps an office at the Heinz Center, which is only three blocks from the White House. What pays his salary these days is George Mason University, where he teaches a seminar in the spring on problems in conservation and conservation biology. The other part of his job description is working with the dean and the provost to help them build their environmental and science programs. They are exploring a dual masters degree with the University of Brasilia, and George Mason also recently launched an undergraduate program of study in partnership with the Smithsonian. Students spend an entire semester getting practical experience at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, learning from prominent researchers and educators.

Here’s what I would say to young people who are looking at the environmental challenge today and wanting to make a difference: first of all, you really can make a difference. And second, no matter how gloomy a situation looks, nothing’s over till it’s over.

Tom has been the recipient of numerous awards including the Grand Cross of the Order of Scientific Merit, the John & Alice Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, the BBVA

Tom at the Heinz Center in 2009

Tom with Al Gore in 2006

Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award for Ecology and Conservation Biology, and the National Geographic Conservation Fellowship. Most recently Tom was awarded the 2012 Blue Planet Prize in Tokyo for being “the first scientist to academically clarify how humans are causing habitat fragmentation and pushing biological diversity towards crisis.” In recognition of this prize, Former President Bill Clinton wrote the following about Tom,

“Your career has been a precious gift to our planet and to all life that inhabits it. You have not only elevated awareness of our environmental challenges, but offered practical solutions as well. I’m proud to have signed the Tropical Forest Conservation Act of 1998, putting into practice the ‘debt for nature swap’ mechanism you developed to finance international conservation efforts. And finally, while acknowledging the urgent need for a global commitment to sustainability, you have been unwavering in your optimism that we can solve anything if we all work together.”

1997, at the Rio +5 Forum

It is no surprise, then, that Tom is referred to as “the Planet Doctor” by many of his colleagues and admirers. The late founder of our zoo would be so pleased with his disciple and all of Tom’s efforts to educate his fellow human beings to be stewards of our planet.

Tom’s association with Millbrook has been indelibly linked for the past 58 years. When he was a Yale undergraduate, Tom would return to campus and assist the Trevors in the biology lab and at the zoo. He was elected to the board of trustees in 1971, and he remains active as an honorary trustee today. His daughter, Kata, graduated from Millbrook in 1986, and we hope that Tom may be a grandfather of a Millbrook student in the very near future. That grandchild will surely come to share in the passion that Frank Trevor instilled in Tom, a passion that continues to grow at Millbrook.

Tom joined classmates for their 50th reunion in 2009