21 minute read

THIERRY FISCHER CONDUCTS RACHMANINOFF, HONEGGER & NATHAN LINCOLN DE CUSATIS

JANUARY 28 & 29, 2022 / 7:30 PM ABRAVANEL HALL

THIERRY FISCHER, conductor MADELINE ADKINS, violin

HONEGGER

Symphony No. 3, “Symphonie liturgique” I. Dies irae II. De profundis clamavi III. Dona nobis pacem

NATHAN LINCOLN de CUSATIS

The Maze for Violin and Orchestra (Western US Premiere, commissioned by Madeline Adkins) I. Echoes II. The Overlook III. Pictographs IV. The Confluence

Madeline Adkins, violin

INTERMISSION

RACHMANINOFF

Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 I. Non allegro II. Andante con moto (Tempo di valse) III. Lento assai - Allegro vivace

CONCERT SPONSOR

C. COMSTOCK CLAYTON FOUNDATION

See page 13 for Thierry Fischer’s profile.

Madeline Adkins

Violin

GUEST ARTIST SPONSOR Violinist Madeline Adkins joined the Utah Symphony as Concertmaster in September 2016. Prior to this appointment, she was a member of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, performing as Associate Concertmaster from 2005-16. She was also Concertmaster of the Baltimore Chamber Orchestra from 2008–16.

Adkins is a Concertmaster of the Grand Teton Music Festival Orchestra and has served as Guest Concertmaster of the Pittsburgh Symphony, Cincinnati Symphony, Houston Symphony, Hong Kong Philharmonic, Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, and Grant Park Symphony. Adkins has also been a guest artist at numerous festivals including the Stellenbosch International Chamber Music Festival in South Africa, Sarasota Music Festival, Jackson Hole Chamber Music, Music in the Mountains, and Sewanee Summer Music Festival, as well as a clinician at the National Orchestral Institute, National Youth Orchestra at Carnegie Hall, and Haitian Orchestra Institute. In addition, she has served as Music Director of the NOVA Chamber Music Series in Salt Lake City. A sought-after soloist, Adkins has appeared with orchestras in Europe, Asia, Africa, and 24 US states, including over 25 works as soloist with the BSO, and seven concertos as soloist with the Utah Symphony.

The daughter of noted musicologists, Adkins is the youngest of eight children, six of whom are professional musicians. The siblings, who included titled players in the National, Dallas, and Houston Symphonies, joined together to form the Adkins String Ensemble. She performed on viola and violin with this unique chamber ensemble for over 15 years, and the group has made numerous recordings, including Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht.

Adkins serves as a Musician Director on the Board of the Grand Teton Music Festival. When not on stage, Adkins enjoys travel photography, reading, tap dancing, and exploring the West. She is also passionate about animal rescue, and has fostered over 100 kittens! Adkins volunteers regularly for Best Friends Animal Society, the Utah Food Bank, and the International Rescue Committee.

By Jeff Counts

Symphony No. 3, “Symphonie liturgique”

Duration: 33 minutes in three movements.

THE COMPOSER – ARTHUR HONEGGER (1892-1955) – Author and music annotation legend Michael Steinberg saw something worth investigating in Honegger’s selfreported “dual nationality”. He might have been on to something. Honegger was born in Paris to Swiss parents and though his adopted French home defined his artistic nationality, at least by reputation, he credited his Helvetic roots for many of his most deeply imbedded personal traits, including a “naïve sense of honesty”. The fact that his face adorned the 20 Franc Swiss bank note from 1996–2014 was further proof that this charter member of the Parisian Les Six, devotedly claimed by both of his “homes”, was never just one thing or the other. Honegger was a complex enigma whose music reflected his unique, multifaceted, views on humanity and the world.

THE HISTORY – War informed many of those views. Honegger was in Paris when the Germans came in 1940 and though they attempted to encourage his participation in the cultural confirmation of their occupation, he steadfastly declined. When the war ended in 1945, Honegger set to work on a new symphony that would be “a drama, between three characters, real or symbolic: misery, happiness and man.” “These are eternal themes”, he continued in his description of Symphony No. 3’s intent, “I have attempted to bring them up to date.” Among Honegger’s many “dualities” was his Protestant DNA as a Swiss-born person and his growing embrace of France Catholicism as an adult. The three movements of Symphony No. 3 were drawn from the latter influence. Based on elements of the Liturgy, the music embodies Honegger’s three characters in order, with terror in the face of divine and violent wrath, the loss of contentment after being so cruelly abandoned by divinity and the resigned, tentative peace that comes only from active rebellion. World War II can’t be thanked for much beyond the overarching triumph of good over evil. But the artistic response to those terrible years did yield great, lasting works. Composers from Shostakovich to Messiaen to Britten (the list is much too long to fully present here) created urgent cautionary testaments to their separate realities and left us a canon of remembrance that is as meaningful today as it was then. Honegger’s masterful contribution to this effort with the “Liturgique” Symphony has perhaps not won him the same recognition as others, but he has never truly been in their league anyhow. Popularity is not the same thing as importance, however, and Honegger’s place in history was best affirmed by Jean Cocteau at the composer’s funeral. “Arthur,” Cocteau told the gathered many, “you managed to gain the respect of a disrespectful era.” He deserves so much more in ours.

THE WORLD – Elsewhere in 1946, It’s a Wonderful Life premiered in America, the Philippines gained independence, Mensa was founded in England, and Juan Perón was elected in Argentina.

THE CONNECTION – Honegger’s Symphony No. 3 has not been performed by the Utah Symphony since 1985. George Cleve conducted.

The Maze

Duration: 18 minutes in four movements.

THE COMPOSER – NATHAN LINCOLN DE CUSATIS (b. 1982) – One biography of Fordham University Associate Professor Nathan Lincoln de Cusatis describes him as a composer with an “inclusive musical voice.” This observation, like the artistic generosity it praises, comes from his wideranging influences and interests. The music of Lincoln de Cusatis reflects a life spent exploring both jazz and classical idioms, with other more oblique inspirations filling in the spaces in between. The biography continues: “His work is often guided by psychological narratives that unfold through references to past musical traditions, communal improvisation, cult films, iconic works of art and the ambient sounds of the urban landscape.”

THE HISTORY – Non-urban landscapes provide the source material for The Maze for Violin and Orchestra (2019). Commissioned by Utah Symphony Concertmaster Madeline Adkins, this piece is described on her website as “inspired by the Maze District of Canyonlands National Park, one of the most isolated and pristine desert wilderness areas in the country.” Adkins further explains that Lincoln de Cusatis “travelled the Maze in March 2019, spending six days covering the entirety of the district…This piece is his attempt to capture that journey in sound, and to use the temporal dimension of music to translate the vastness of geologic time and change to the human scale.” Cast in four continuous movements, The Maze begins with “Echoes.” According to Lincoln de Cusatis, this movement serves as an introduction to two of the main ideas that run through the experience – an eerie sonic representation of the desert he calls the “chord of mystery” and a melodic trailhead known as “the echo” that marks the topographical and emotional starting point of the hike. “The Overlook” depicts the geologic forces behind canyon formation while pitting the soloist against the physical barriers to entry in such a place. As she descends from the rocky rim to the floor of the Maze itself, she figuratively “chases” the erosion that created everything around her. “Pictographs” pauses the soloist/ traveler near the entrance of the Maze to take in the famous Harvest Scene of cave paintings. Here, ancient gods, creation myths, and other elemental mysteries are given voice after centuries of silence. The finale of The Maze is, of course, at “The Confluence” of the Green and Colorado rivers. Lincoln de Cusatis gives each water course its own contrasting rhythmic identity as we hear the soloist “ride the rapids” to the place where they meet. She is reminded once more by “the echo” of how her journey began before finally climbing up and out of this place of suspended time and immeasurable space.

THE WORLD – Elsewhere in 2019, protests heated up in Hong Kong, Notre Dame Cathedral burned, Japanese Emperor Akihito abdicated, and Greta Thunberg addressed the UN Climate Action Summit.

THE CONNECTION – Though Concertmaster Madeline Adkins has appeared as soloist many times, these concerts represent the Utah Symphony premiere of Nathan Lincoln de Cusatis’ The Maze.

Symphonic Dances, Op. 45

Duration: 35 minutes in three movements.

THE COMPOSER – SERGEI RACHMANINOFF (1873-1943) – Like so many of his artistic cohort in the eventful moments of 1939, Rachmaninoff decided that Europe was no place to be. He had seen it all before and knew well the sound made by distant drums of war. And at his age (he had recently fallen and was forced to miss the ballet based on his Paganini Variations), the prospect of another global conflagration was more than he was prepared to endure. He was living in Switzerland at the time but was traveling regularly for concerts in the U.S. and England. His decision to flee more permanently to America was fateful. It meant he would never see his beloved Swiss villa, let alone his long-lost Russian homeland, again.

THE HISTORY – In the latter years of his compositional life, Rachmaninoff favored a leaner and more focused orchestral language. The luxuriant textures that fueled his rise to prominence became rare and in their place was a more concise, less emotional presentation of ideas. Rachmaninoff’s somber seriousness as a person was often at odds with his early Romantic opulence as a composer, so the turn towards directness in his December years is perhaps an understandable eventuality. In his last completed work, Rachmaninoff found reason to blend a bit of the old with the new. The Symphonic Dances of 1940 actually date in part back to 1915 and a ballet project that Rachmaninoff had proposed to Mikhail Fokine. Nothing came of it, so the material in those sketches remained on the shelf for twenty-five years before finding a new home in the score of Symphonic Dances. The work was dedicated to Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra and, though not an overwhelming success at the premiere, Symphonic Dances is regularly and quite reasonably held up as Rachmaninoff’s finest masterpiece. The spare angularity of his late style was reminiscent of his countrymen Stravinsky and Prokofiev but the lushness of his harmonic language and the occasional, well-placed “big” melody (in honor of his own younger self) are elements that still brook no comparison, since no composer before or since has ever truly matched them. Present also of course was the Dies Irae chant that shadowed Rachmaninoff throughout his life and figured prominently in his final three large-scale works. “Last” works almost always beg a summative place in a composer’s history. The music itself, so often incomplete, does not always oblige. But with Symphonic Dances, no stretch is needed to see it as a capstone to a brilliant career.

THE WORLD – Elsewhere in 1940, Winston Churchill became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first McDonald’s restaurant opened, and Lhamo Thondup was officially installed as the 14th Dalai Lama in Tibet.

THE CONNECTION – Symphonic Dances was recorded by Utah Symphony in 2004 and last performed live in 2017. Matthias Pintscher was on the podium.

UPCOMING PERFORMANCES AT THE UTAH SYMPHONY

THIERRY FISCHER CONDUCTS RACHMANINOFF, HONEGGER & NATHAN LINCOLN DE CUSATIS January 27 / Austad Auditorium at the Val A. Browning Center (Ogden) January 28 & 29 / Abravanel Hall Featuring Madeline Adkins, violin Composer Nathan Lincoln de Cusatis takes us on a sonic trek through the canyonlands in a work commissioned and performed by Concertmaster Madeline Adkins.

THIERRY FISCHER CONDUCTS RAVEL, LISZT & JOHN ADAMS February 3 / Austad Auditorium at the Val A. Browning Center (Ogden) February 4 & 5 / Abravanel Hall Joyce Yang, piano Just try to sit still during Maurice Ravel's homages to two of the world's greatest waltz composers, Franz Schubert and Johann Strauss.

BRAVO BROADWAY! A RODGERS & HAMMERSTEIN CELEBRATION February 10 / Austad Auditorium at the Val A. Browning Center (Ogden) February 11 & 12 / Abravanel Hall Jerry Steichen, conductor Let us transport you back to the Golden Age of Broadway with a tribute to Rodgers and Hammerstein. DANIEL LOZAKOVICH PLAYS TCHAIKOVSKY'S VIOLIN CONCERTO February 18-19 / Abravanel Hall Thierry Fischer, conductor Daniel Lozakovich, violin Composed during the worst year of his life and written off as pretentious and unplayable, Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto has risen to the highest ranks of the virtuoso repertoire.

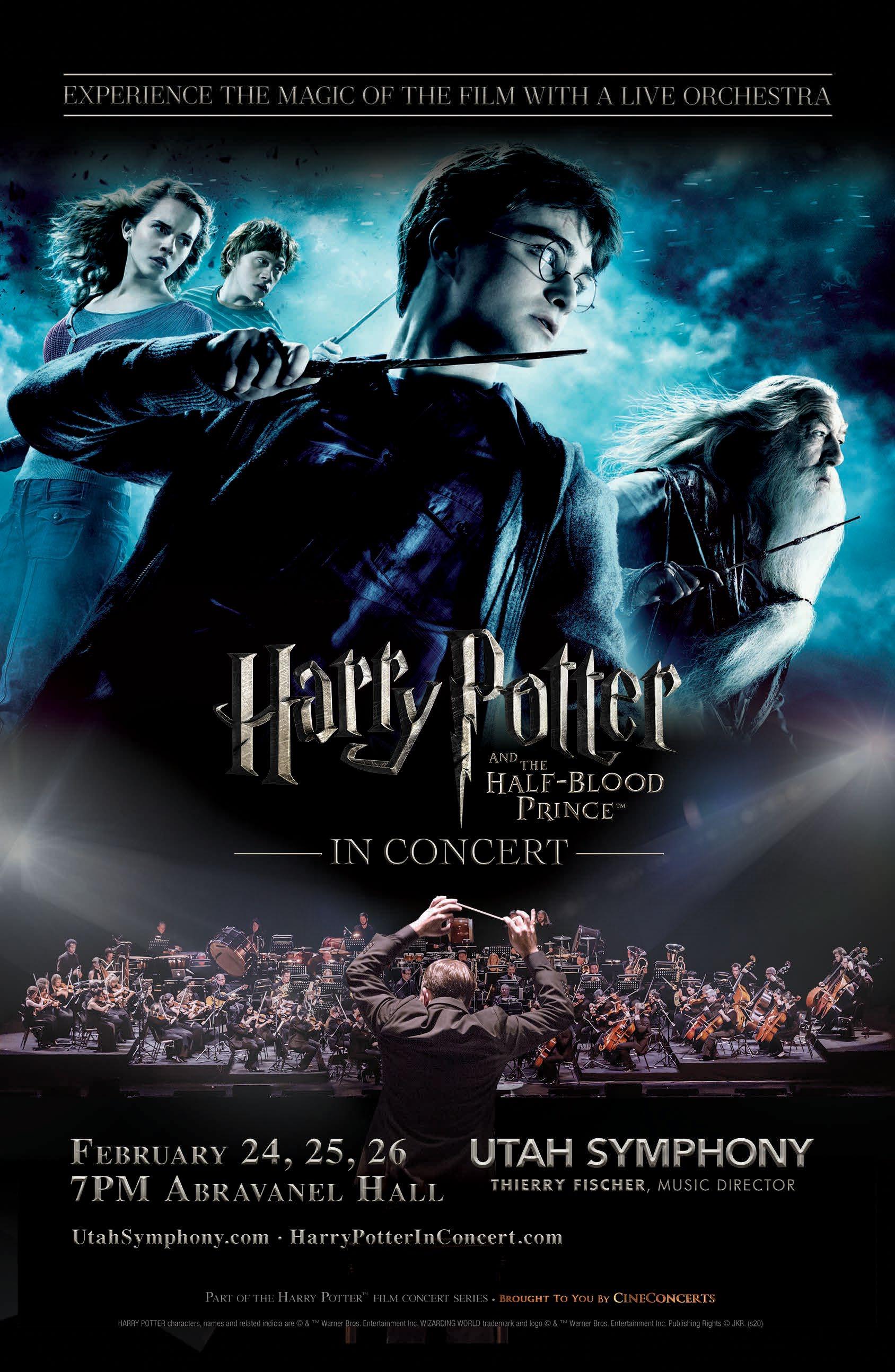

HARRY POTTER AND THE HALF-BLOOD PRINCE™ IN CONCERT February 24-26 / Abravanel Hall Conner Gray Covington, conductor Relive the magic of year six in Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince™ in Concert with the Utah Symphony.

LOUIS SCHWIZGEBEL PLAYS MOZART'S PIANO CONCERTO NO. 12 WITH SHOSTAKOVICH SYMPHONY NO. 5 March 3 / The Noorda Center for the Performing Arts (Orem) March 4 & 5 / Abravanel Hall Francesco Lecce-Chong, conductor Louis Schwizgebel, piano Witness "A Soviet Artist's Response to Just Criticism" in history's most famous musical apology.

THIERRY FISCHER CONDUCTS RAVEL, LISZT & JOHN ADAMS FEBRUARY 4 & 5, 2022 / 7:30 PM ABRAVANEL HALL

THIERRY FISCHER, conductor JOYCE YANG, piano

JOHN ADAMS

Slonimsky’s Earbox

LISZT

Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major for Piano and Orchestra I. Allegro maestoso II. Quasi adagio - Allegretto vivace III. Allegro marziale animato Joyce Yang, piano

INTERMISSION

RAVEL

Une Barque sur l’océan

Valses nobles et sentimentales I. Modéré II. Assez lent III. Modéré IV. Assez animé V. Presque lent VI. Assez vif VII. Moins vif VIII.Epilogue

La Valse

CONCERT SPONSOR

HEALTHCARE NIGHT

CONDUCTOR SPONSOR

See page 13 for Thierry Fischer’s profile.

Joyce Yang

Piano

GUEST ARTIST SPONSOR

NORA ECCLES TREADWELL FOUNDATION

Joyce Yang first came to international attention in 2005 when she won the silver medal at the 12th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. The youngest contestant at 19 years old, she took home two additional awards: Best Performance of Chamber Music (with the Takács Quartet), and Best Performance of a New Work.

Other notable orchestral engagements have included the Chicago Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, the BBC Philharmonic, as well as the Toronto, Vancouver, Sydney, Melbourne, and New Zealand Symphony Orchestras. She was also featured in a five-year Rachmaninoff concerto cycle with Edo de Waart and the Milwaukee Symphony, to which she brought “an enormous palette of colors, and tremendous emotional depth” (Milwaukee Sentinel Journal).

Born in 1986 in Seoul, South Korea, Yang received her first piano lesson from her aunt at the age of four. She quickly took to the instrument, which she received as a birthday present. Over the next few years she won several national piano competitions in her native country. By the age of ten, she had entered the School of Music at the Korea National University of Arts, and went on to make a number of concerto and recital appearances in Seoul and Daejeon. In 1997, Yang moved to the United States to begin studies at the pre-college division of the Juilliard School with Dr. Yoheved Kaplinsky. During her first year at Juilliard, Yang won the pre-college division Concerto Competition, resulting in a performance of Haydn’s Keyboard Concerto in D with the Juilliard Pre-College Chamber Orchestra. After winning the Philadelphia Orchestra’s GreenfieldStudentCompetition, she performed Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with that orchestra at just 12 years old. She graduated from Juilliard with special honor as the recipient of the school’s 2010 Arthur Rubinstein Prize, and in 2011 she won its 30th Annual William A. Petschek Piano Recital Award.

Yang appears in the film In the Heart of Music, a documentary about the 2005 Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. She is a Steinway artist.

By Jeff Counts

Slonimsky’s Earbox

Duration: 23 minutes.

THE COMPOSER – JOHN ADAMS (b. 1947) – Among the most generous and beguiling of our compositional living legends, John Adams seems to somehow choose his subjects with both great care and complete abandon. From an imagined familiarity between his father and Charles Ives to a strange book he discovered in a French farmhouse to a bluesy phrase impossibly attributed to Martin Luther, John Adams almost always titles his pieces in a way that requires further reading. It is hardly a surprise then that he would find common cause with one of the wittiest and most intellectually virtuosic voices in musical letters.

THE HISTORY – Known more in America for his Lectionary of Music and Lexicon of Musical Invective, Nicolas Slonimsky was a Russian-born polymath who, looking back on the 101 years of his life before passing away in 1995, could have boasted no less than four distinct careers in music. Slonimsky was a pianist, a conductor, a composer, and a highly praised lexicographer with an inexhaustible supply of anecdotes. Adams got to know him when they both were living in Santa Monica, California. Slonimsky was, according to Adams, “a character of mind-boggling abilities” who could “recall with absolute precision the smallest detail of something he’d read from forty years before.” Slonimsky’s Earbox (1995) owes its existence to something Slonimsky had written well over forty years before. The Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns dates from 1947 and Adams acknowledged a great personal debt to it by stating that the “scales and resulting harmonies have had a singular impact on my music since the Chamber Symphony of 1992.” Further inspiration for Slonimsky’s Earbox is attributed by Adams to Igor Stravinsky, whose orchestral work Le chant du rossignol uses the orchestra to “burst[s] out in a brilliant eruption of colors, shapes and sounds.” Adams was also drawn to Stravinsky’s use of modal scales and harmonies in the Rossignol score. These had an obvious, direct-line connection for Adams to Slonimsky’s treatise, but additionally supported a long-held theory of Adams’ that “the Russians…had begun something very important with their use of modal scales…a direction that unfortunately was overwhelmed by more prestigious practices such as Neoclassicism and Serialism.” It’s exactly the kind of brainy observation Slonimsky himself might have made and clear proof that Adams and his muse were made for each other. The “Earbox” of the title comes from Adams too, who called it “a word worthy of Slonimsky himself, a coiner who never tired of minting his own.” Yet more proof. If you need it.

THE WORLD – Elsewhere in 1995, the “Trial of the Century” concluded in OJ’s acquittal, the Bosnian Civil War ended, the World Trade Organization was founded, and the city of Bombay changed its name to Mumbai.

THE CONNECTION – These performances mark the Utah Symphony’s first performances of John Adams’ Slonimsky’s Earbox.

HISTORY OF THE MUSIC

Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major

Duration: 19 minutes in four movements (played without pause).

THE COMPOSER – FRANZ LISZT (1811–1886) – Liszt spent the 1850s in Weimar and created some of his finest works there, including the two piano concertos, Totentanz, the Faust Symphony, as well as various etudes, rhapsodies and other sundry exercises. In addition to continuing his duties under the fabulous title of Kapellmeister Extraordinare, the composer had officially relocated to Weimar in 1848 (perhaps seen then an odd choice for someone of his stature) because of two important people, his employer and his second great love. With Grand Duke Carl Alexander, Liszt hoped he might co-found an intellectual “Athens of the North” and in the Princess Carolyne he saw nothing less than his future wife. Neither dream would be realized.

THE HISTORY – Both of Liszt’s piano concertos had long incubation periods. No. 1 was apparent in sketches from the early 1830s (possibly even before) and, though ostensibly “complete” by the end of that decade, it was revised repeatedly over the next two and not premiered in its final form until 1855. Liszt, ever preoccupied with structural innovation and recalling an 1836 admonishment by Robert Schumann to “invent a new form”, chose to set his concerto as a continuous flow of ideas rather than a standard three-movement work with breaks in between. Compared to the nearly contemporaneous Concerto No. 2 which, according to the previously quoted essayist Michael Steinberg is “for poet’s only”, No. 1 is a simple dazzler for any “keyboard athlete.” We should be careful, however, not to let assessments of this music’s showy nature (which are common and fair) blind us to its truly novel formal accomplishments. Other composers certainly noticed and, as with so much of what Liszt did throughout his composing life, they saw glimpses of the future in his intrepid, boisterous spirit. He well knew this about himself and cultivated it carefully. In fact, a wonderful legend about the concerto’s opening theme plays neatly into the notion of Liszt as a man fully aware, and perhaps a bit protective, of his place in the vanguard. According to the lore, Liszt and his son-in-law Hans von Bülow put secret words to the notes which (translated) say “None of you understand this, haha!” That dismissal, if true, seemed to predict and then casually wave away the opinion of critics and colleagues that Concerto No. 1 lacked the “poetry” mentioned above. It also baked in a reminder that, for all his swagger and fame, Liszt was an artist of incredible intellectual depth, and one willing to remind you of such if you forgot.

THE WORLD – Elsewhere in 1855, Alexander II ascended to the Russian throne, The Daily Telegraph began publication in London, and the first bridge over the Mississippi River was constructed in Minneapolis.

THE CONNECTION – Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 1 was most recently performed by the Utah Symphony in 2007 with Keith Lockhart on the podium and Lise de la Salle as soloist.

HISTORY OF THE MUSIC

Three Orchestral (?) Masterpieces

Duration: Une barque sur l’océan – 7 minutes; Valses nobles et sentimentales – 16 minutes; La Valse – 12 minutes

THE COMPOSER – MAURICE RAVEL (1875–1937) – For years, Ravel and Debussy were set up as rivals in Paris and, though they did not choose or nurture this “conflict,” the eventual factionalization of their artist community led to a cooling between them. It’s a shame, since the compositional similarities necessary to occasion such a competition were largely invented. Neither man liked being called an Impressionist (which they were then and still are today) and likely resented how the superficiality of the designation masked their individuality as artists. That said, it is difficult to fault their contemporaries for declaring them kindred. In addition to their comparable harmonic and formal innovations, both composers wrote prodigiously and colorfully for the piano. And both liked to convert those works into orchestral masterpieces.

THE HISTORY – Ravel wrote his piano collection Miroirs (Reflections) during 1904 and 1905. In his description of the music, he bristled (lightly) by admitting he knew the title would invite the expected tag of Impressionism. It was “a rather fleeting analogy,” he said, “since Impressionism does not seem to have any precise meaning outside the domain of painting.” No. 3 of the set was Une barque sur l’océan (A Boat on the Ocean) and it was no doubt measured against Debussy’s La Mer when it was orchestrated in 1906. The title of Valses nobles et sentimentales, Ravel wrote, “sufficiently indicates that I was intent on writing a set of Schubertian waltzes.” Comprising seven dances and an epilogue, the Valses were orchestrated in 1912 and were Schubertian by dedication only. Unlike the separate parts that made up Schubert’s Valses nobles and Valses sentimentales sets, Ravel’s waltzes are indistinct, interconnected and decidedly modern by comparison. A few of the harmonic departures from expectation, in fact, earned Ravel some catcalls at the piano version premiere. Given this fascination with the waltz form, it comes as no surprise that Ravel long entertained the idea of creating an homage work to Johann Strauss, Jr. entitled Wien (Vienna). When Serge Diaghilev approached him after World War I to write a new ballet, he thought he had finally found reason to see it through. Ravel gave the impresario a two-piano sneak peek of Wien in the spring of 1920. Poulenc and Stravinsky were in attendance as well and Poulenc recalled the disastrous tension when Diaghilev referred to the music as “genius” but “not a ballet.” Ravel was highly offended and broke ties with Diaghilev on the spot. So enduring was the animosity between them that it is believed Diaghilev challenged Ravel to a duel a few years later. La Valse (the only part of tonight’s concert trio that didn’t begin life as a piano piece) premiered later in 1920, but not as a ballet.

THE WORLD – Elsewhere in 1906, the San Francisco earthquake occurred. In 1912, the RMS Titanic went down during its maiden voyage. And in 1920, the very first “Ponzi” scheme was born.

THE CONNECTION – La Valse was last programmed in 2015. Valses nobles et sentimentales appeared last in 1999. And Une barque sur l’océan was previously presented in 2015.