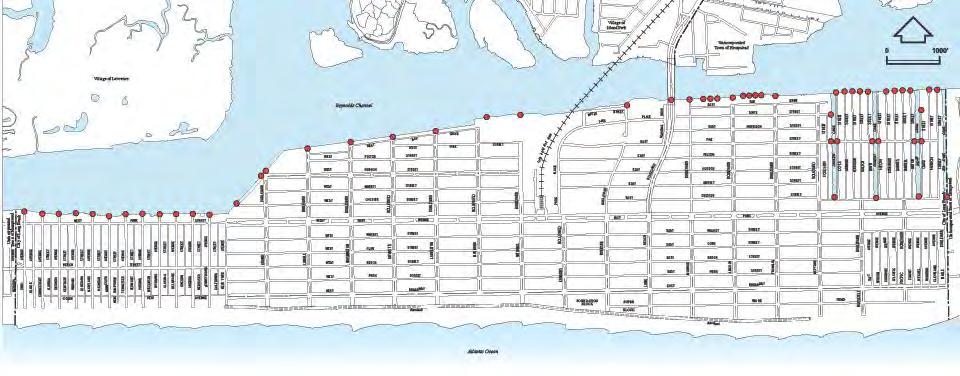

CITY OF LONG BEACH

COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2022–2032

ADOPTED: AUGUST 1, 2023

ADOPTED: AUGUST 1, 2023

The City of Long Beach Comprehensive Plan 2022–2032 was prepared with the input of elected officials, community leaders and volunteers, business owners and residents—each of whom contributed their time and their expertise to the goal and strategies that will guide the City for the next decade.

The City of Long Beach would like to thank all those who participated and provided insightful comments and feedback throughout the process. These contributions have guided the preparation of the Comprehensive Plan and ensured that it truly represents Long Beach’s collective vision.

The City of Long Beach would like to especially recognize the contributions of the following people:

John Bendo, City Council President

Elizabeth M. Treston, City Council Vice President

Roy Lester, City Council Member

Karen McInnis, City Council Member

Tina Posterli, City Council Member

Ronald J. Walsh, Acting City Manager

Patricia Bourne, Director, City of Long Beach Economic Development and Planning

John McNally, Director, City of Long Beach Public Relations and Special Projects

Jordan Schieber, Assistant Planner, City of Long Beach Economic Development and Planning

Franklin Alvarado

Steve Candon

Jason Clancy

Vincent DePasquale

Katherine diMonda

Patrick Gallagher

Michael Negri

Tyrone Nurse

Jackey Odom, Honorary Member

Pearl Polite

Eric Sackler

Damian Sciano, Chairman

This Comprehensive Plan is an official policy document prepared by the City, with input from community residents and business owners, that guides the community’s vision and goals for its future. The Comprehensive Plan is a mechanism to promote the health, safety, and general welfare of the City residents, presenting a snapshot of the current state of the City, including an inventory of its natural and built spaces, demographic diversity and housing supply, economic health, natural and cultural resource protection, and resiliency to natural and manmade conditions.

At the beginning of the process, the City and Consultant Team established preliminary objectives for the Comprehensive Plan that were shared with the community at the virtual public meeting on April 21, 2022:

f The Plan should be an expression of goals for the City’s future evolution and a series of actions to achieve those goals;

f The Plan should provide an opportunity for the community to reflect on its collective vision for its future, economic, natural, and social environments; and

“Among the most important powers and duties granted by the legislature to a city government is the authority and responsibility to undertake city comprehensive planning and to regulate land use for the purpose of protecting the public health, safety and general welfare of its citizens.”

—New York State General City Law §28-A

f The Plan goals and strategies should guide the City’s policy decisions and assign action items for short- (2-5 years), medium- (6-10 years), and longterm (+10 years) implementation.

New York General City Law § 28-A.3. (a) (2021) defines a “Comprehensive Plan” as “the materials, written and/or graphic, including but not limited to maps, charts, studies, resolutions, reports and other descriptive material that identify the goals, objectives, principles, guidelines, policies, standards, devices and instruments for the immediate and long-range protection, enhancement, growth and development of the city.”

A COMPREHENSIVE PLAN is a dynamic action document that should evolve with the changing needs of the community.

are similar to, and aligned with, regional, State, and federal programs, the City is well-positioned to seek funding and technical assistance for implementation of capital-intensive initiatives. This Comprehensive Plan recommends coordinating with neighboring communities, regional organizations, and Nassau County to maximize visibility and leverage support.

To prepare this City of Long Beach Comprehensive Plan, the City engaged its residents, business owners, local and regional elected and appointed officials, and leaders in discussions about what is working, what is not working, and how the City views its potential in the short-, medium-, and long-term. The Plan strives to balance many opinions and goals and collectively manage change. This Comprehensive Plan presents a coherent vision of a diverse population—children and seniors, long-term residents, and newcomers— and while aspirational, this vision is grounded in the practical reality of the City’s natural, financial, and physical resources and constraints.

A Comprehensive Plan is required to consider needs, plans, and policy documents proffered and adopted by government entities and regional agencies. To that end, the goals and action items presented herein are based on local priorities for economic growth, housing diversity and security, climate resilience and community quality of life. Because these priorities

This Comprehensive Plan charts a framework the City may follow to meet its goals and provides various options to achieve those goals, though it does not

Having an adopted Comprehensive Plan provides: a FRAMEWORK for the City’s growth management strategy;

GUIDANCE for the City to prioritize future planning, conservation, and development opportunities; and

PREDICTABILITY for City decision-making regarding land use and future development.

Nevertheless, even if zoning code revisions are not proposed or implemented, once a Comprehensive Plan is formally adopted, applications for development submitted to the City’s reviewing boards must be considered in the context of the goals and objectives set out in the Comprehensive Plan.

prescribe specific policies or regulations. Following the adoption of the Comprehensive Plan, the City must review, and revise as necessary, their governing land regulations, including the City’s Zoning Code, natural resource protections and subdivision requirements for consistency and accordance with this Comprehensive Plan. In addition, government agencies that propose capital projects in the City of Long Beach must consider their plans in the context of the City’s Comprehensive Plan.

Through its adoption of this Comprehensive Plan, City of Long Beach leadership affirms the Plan as an official policy document. It is therefore essential the Plan presents consensus-based initiatives. The document presents a vision for the future of the City and includes prioritized achievable actions items supported by the community; the action items are realistic and implementable. The Plan designs a blueprint for use by City government, land use boards, volunteer groups, committees, residents, and business owners to implement recommendations that promote appropriate growth and development.

The Comprehensive Plan:

f Creates a framework for implementing the community’s goals;

f Guides future planning, conservation, growth, land use, and economic investment;

f Thoughtfully considers and incorporates related local and regional planning efforts;

f Ensures potential development is consistent with the City’s planning policies and the community’s needs and priorities; and

f Develops a timeline and assigns specific responsibilities for implementing the Plan’s recommendations.

Adoption of a Comprehensive Plan—on its own— does not alter the City’s land use regulations or zoning code. The Comprehensive Plan is a tool to guide development, but not an instrument to change existing laws and codes. A Comprehensive Plan may recommend changes to the City’s zoning code to achieve the plan’s stated goals; however, enacting actual zoning code revisions requires a separate and distinct process.

If an application is inconsistent with the goals of a Comprehensive Plan, an applicant would need to justify to the relevant reviewing board that the project would not be in contravention with the overall City goals set out in the Comprehensive Plan.

The Comprehensive Plan is divided into six chapters and several accompanying appendices that tell the story of the City of Long Beach’s planning history, where it is today, and lays the groundwork for where it is going into the future.

f Chapter 1: Introduction, Organization, and Context describes the purpose of the Comprehensive Plan, the policy framework, the organization of the document, and previous City of Long Beach planning initiatives.

f Chapter 2: Comprehensive Plan Process and Community Involvement describes and summarizes key findings from the community engagement process and introduces the Vision Statement.

f Chapter 3: Overview of Existing Conditions presents an inventory—in text, graphics, and mapping—of the City’s development patterns, natural and cultural resources, key demographics, and noteworthy trends.

f Chapter 4: Theme Areas with Goals, Strategies, and Action Items synthesizes information described in Chapters 1, 2, and 3. This Chapter is arranged around five key themes: Livable Neighborhoods and Sustained Quality of Life, Thriving Places and Robust Year-Round Economy, Access to Mobility and Connectivity, Enhanced Environment and Climate Resilience, and Sustainable Growth and Opportunities. The public engagement process has informed the goals within each theme. This chapter also presents neighborhood, site-specific, and Citywide strategies, and actions to achieve each goal.

f Chapter 5: Future Land Use Plan is an illustrative presentation of potential land use changes along with land uses to be conserved or to remain as they are based on the goal, strategies, and action steps of the Comprehensive Plan.

f Chapter 6: Conclusion provides the regulatory framework and summarizes next steps for implementation.

f Appendix A: Implementation and Action Plan summarizes action items, assigns responsibility for implementing the action items, and presents a timeline for completion.

f Appendix B: “History and Context of Long Beach,” provided by City of Long Beach staff.

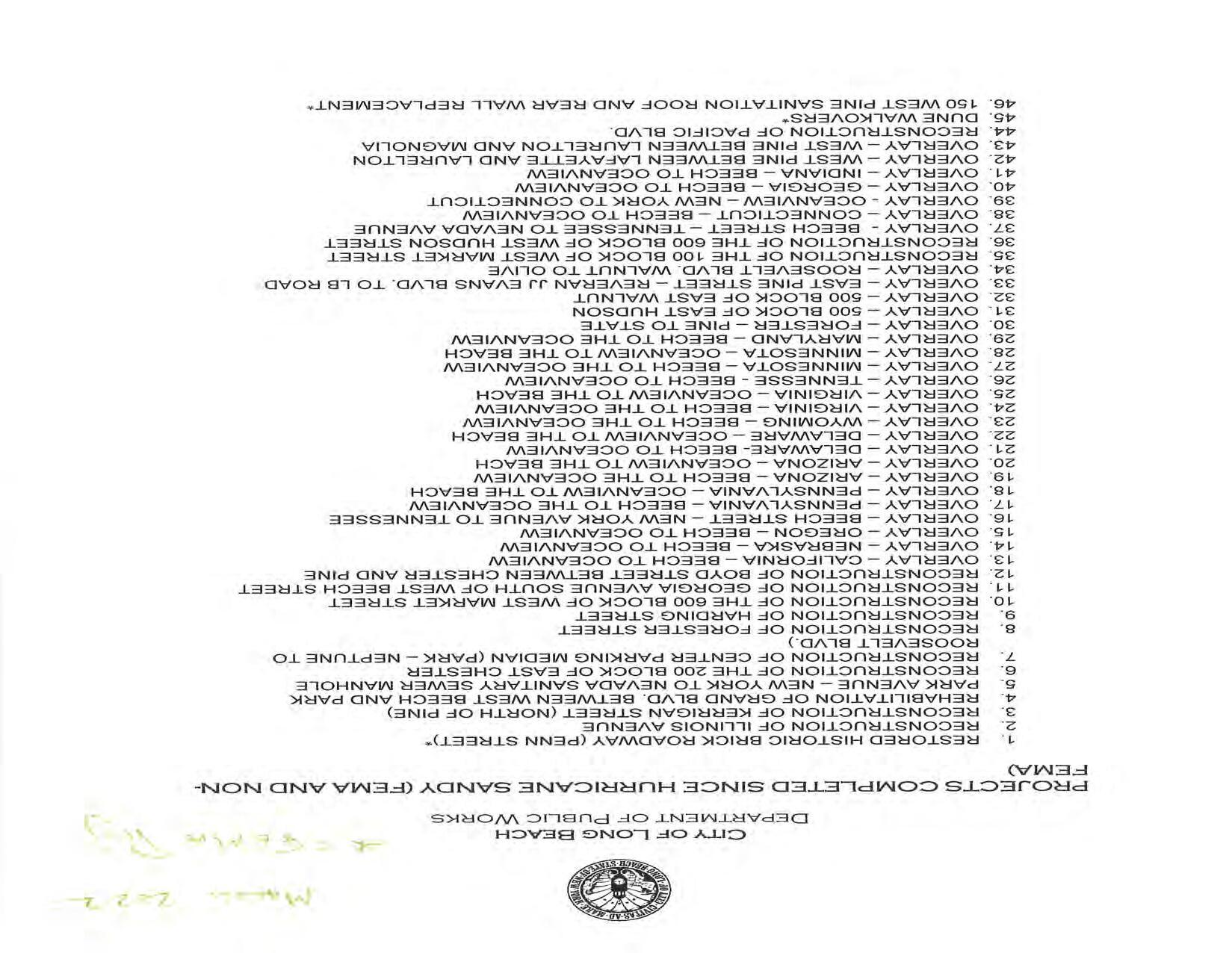

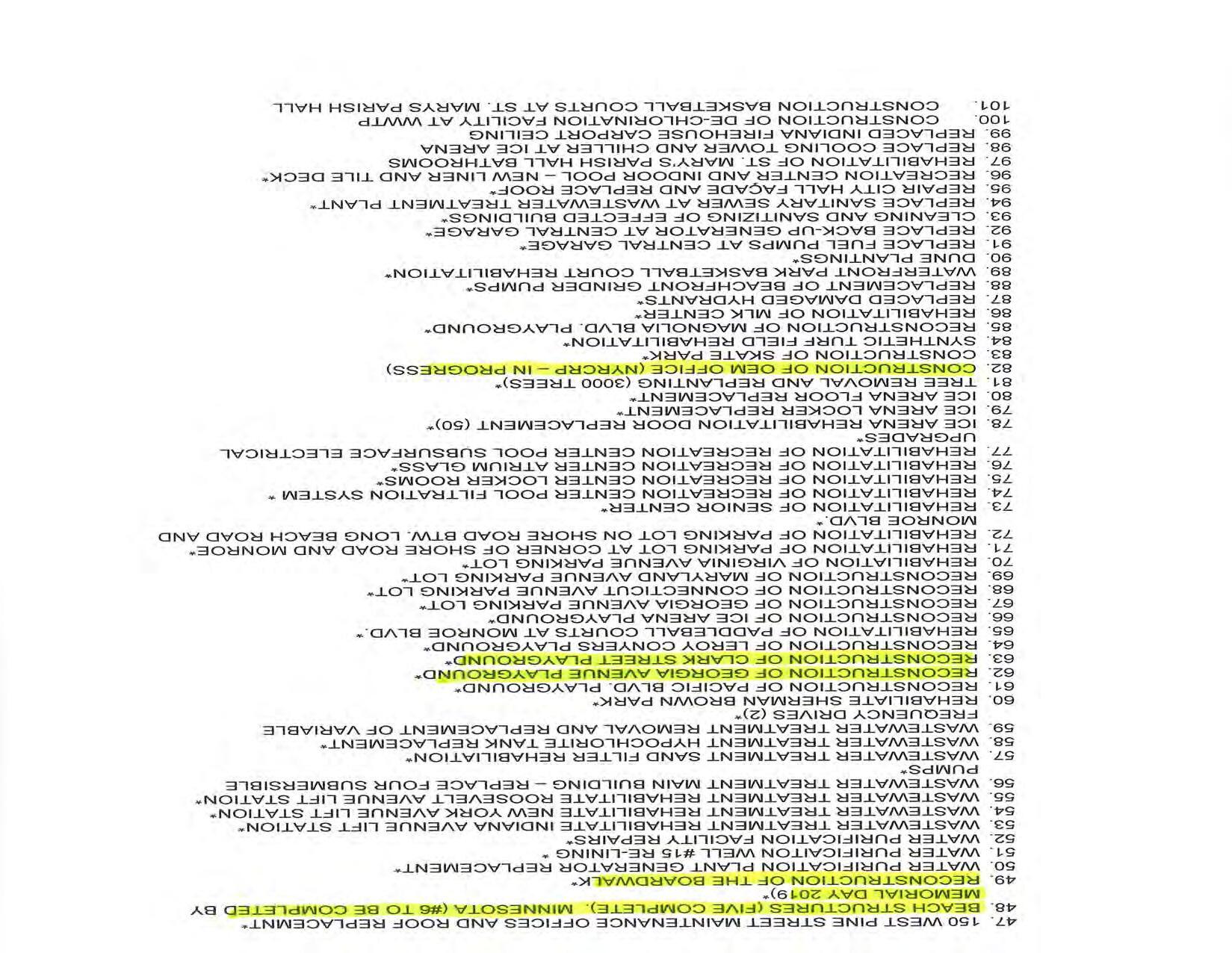

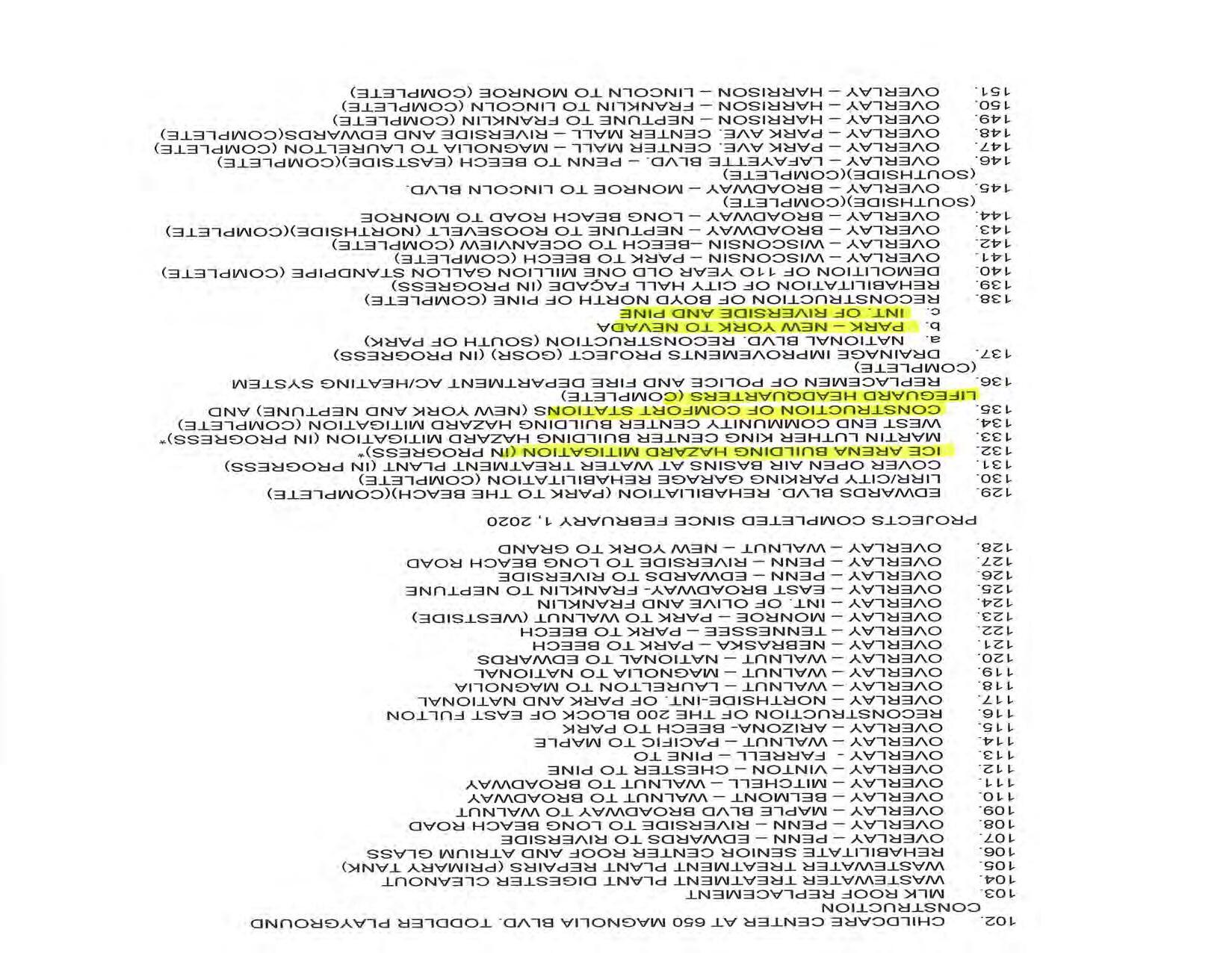

f Appendix C: Recently Completed Resiliency Improvements

f Appendix D: Community Survey Results Report

f Appendix E: Streetsense Commercial District Strategy

f Appendix F: City of Long Beach Comprehensive Plan Final Data Analysis & Existing Conditions

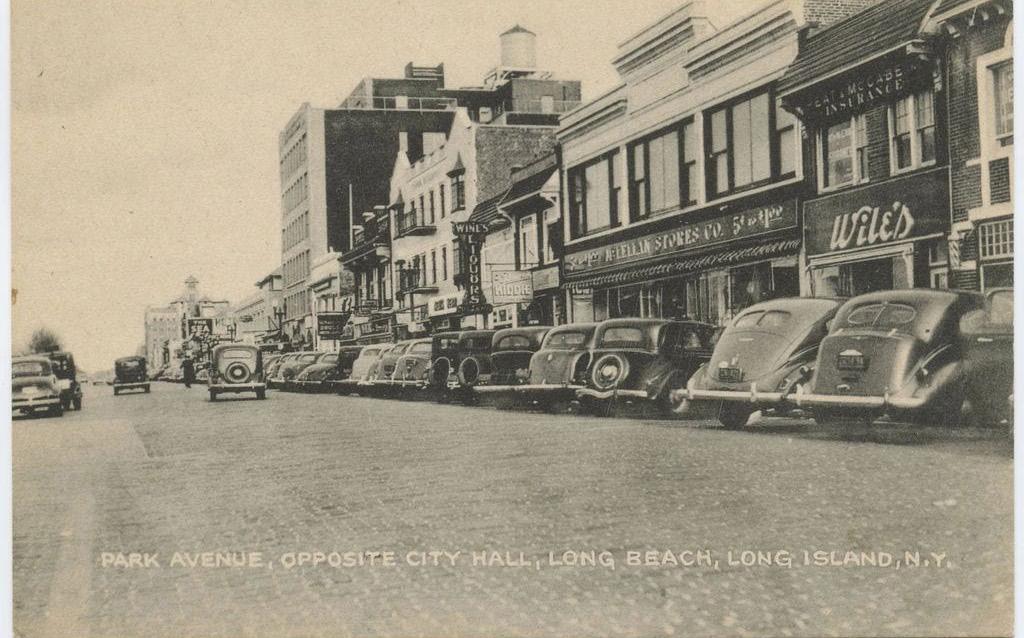

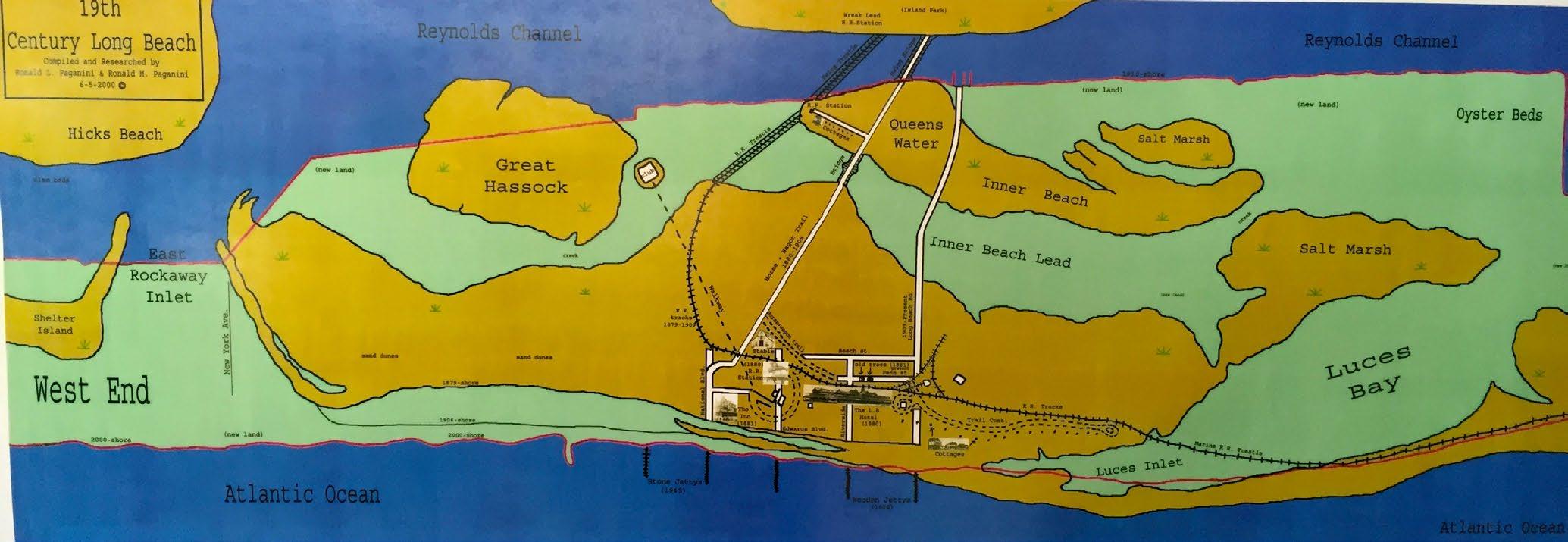

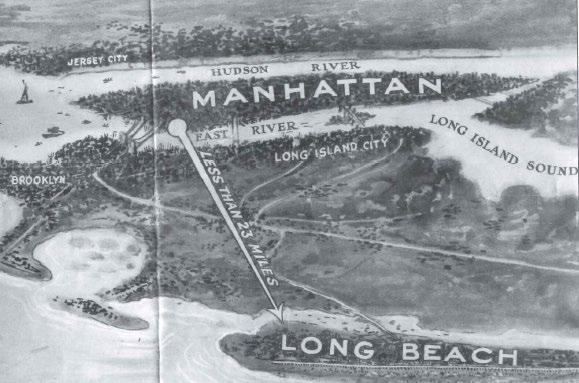

The organization of what is now known as the City of Long Beach began in the 1880s, when the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) extended service to the area. Capitalizing on the availability of public transit to this beach peninsula, the “Long Beach Improvement Company” secured a 100-year lease for the island of Long Beach and built the Long Beach Hotel as a summer resort. Located on the north side of West Broadway and spanning Riverside Boulevard, the Long Beach Hotel was the largest seaside hotel in the world, offering 5,000 guest rooms and a lobby that hosted public meeting rooms and the City’s first post office. The first Long Beach boardwalk ran across the length of the hotel property, connecting visitors from buildings in the hotel complex to the beach and bathing pavilion.

In 1906, Senator William Reynolds purchased both the Long Beach Hotel and the railroad lease. One year later, the Hotel mysteriously burned down, taking with it adjoining cottages, the hotel dormitory, the chapel, a power plant, and two strings of LIRR cars.

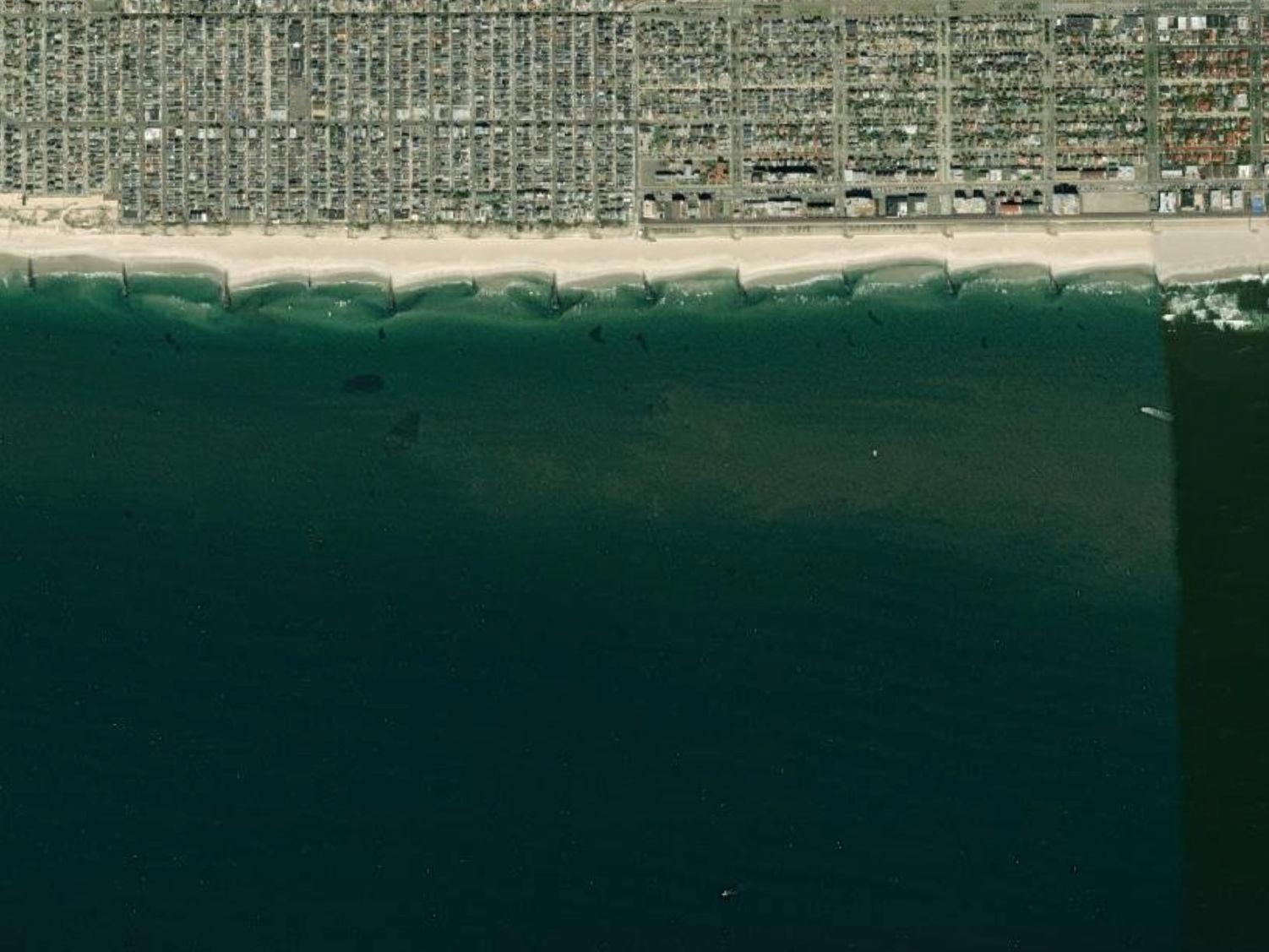

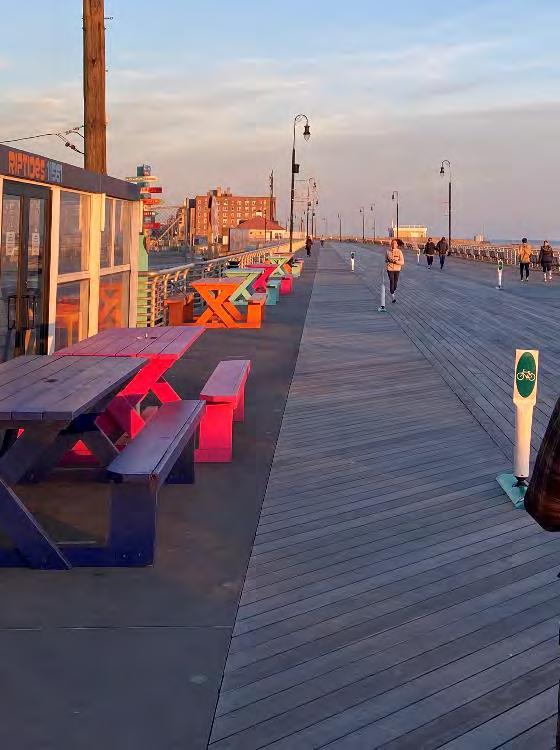

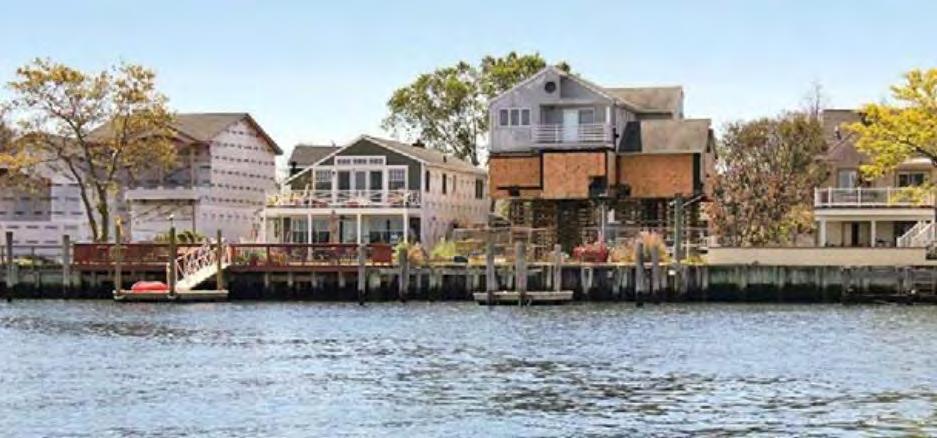

S City of Long Beach Dunes and Beach

1 The following sources were used in this section: City of Long Beach Comprehensive Plan, 2007, Saccardi & Schiff, Inc.; Long Beach New York Rising Community Reconstruction Plan, March 2014; The “History and Context of Long Beach,” provided by City of Long Beach staff, is available in Appendix B

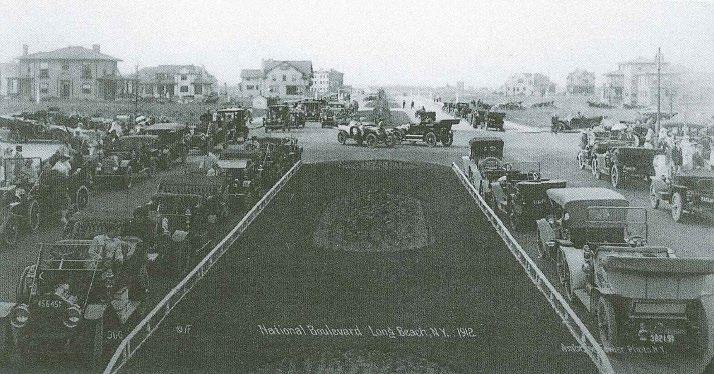

Undeterred, Senator Reynolds pursued developing Long Beach into a seaside planned community, implementing innovative engineering methods to build an “indestructible” 50-foot-wide boardwalk that was 10 feet above the high-water line and supported by concrete piles. The boardwalk was completed in 1914.

When Senator Reynolds first arrived in Long Beach, the area was mostly swampland. As work progressed on the new boardwalk, the material gained by dredging the marshland waters was supplemented with imported soil and used to create a solid island land mass. By 1913, under the umbrella of the Estates at Long Beach Company, Senator Reynolds had developed 200 mansions bordering the new boardwalk along the Atlantic Ocean. The remnants of the original red brick streets can still be found in parts of Long Beach, such as on West Penn Street. In 1922, the City of Long Beach was incorporated.

During World War I and then again during World War II, Long Beach was mainly utilized by the military. This postwar legacy is represented by the pedestrian neighborhood known as the Walks, located between Lindell and New York Boulevards, so named due to its proximity (within walking distance) to the military hospital located at the Nassau Hotel. By the end of

World War II, Long Beach was starting to develop into a middle-class residential and entertainment community. The first school occupied a room in the Nassau Hotel, and the boardwalk attracted familyfriendly recreation activities.

In the 1950s, Long Beach’s boardwalk remained a vibrant recreational center, though it began showing the wear and tear of its age, impelling the City to look at new ways to generate capital to support infrastructure improvements. Thus began the development of apartment buildings, some on former hotel sites, overlooking the Atlantic Ocean.

During the 1970s, when New York State began decommissioning psychiatric hospitals, some of Long Beach’s underutilized hotels were converted to long-term stay facilities to house this population. These uses were short-lived, however, as local officials pushed for amendments to New York State’s regulations regarding adult-care facilities. Pressure to decentralize care facilities to smaller, scattered site community-based housing forced some facilities to close, returning large development sites to the real estate marketplace. Redevelopment of the hotel sites for upscale multi-family residences helped to usher in a renaissance for the City that continues today.

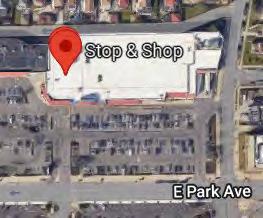

Throughout the 1980s, renewal efforts resulted in upgrades to the City’s sewer and roadway infrastructure and economic development initiatives, including the development of the seven-acre Stop and Shop Shopping Plaza. Since then, Long Beach has welcomed new commercial and retail development, and, generally, retail vacancy rates have remained low. Renewal initiatives also resulted in economic and social separation, using eminent domain, single-use zoning, and street design. The City has addressed, and will continue to address, the consequences of prior policies and actions by improving connectivity, incentivizing multi-use projects, and identifying vacant and underutilized sites to catalyze economic development that is consistent and complementary of the context and character of the neighborhoods in which they are located. The City has identified several parcels, including the Stop and Shop Shopping Plaza, as opportunity sites for redevelopment (see Theme 4.5 of this Comprehensive Plan). Revitalizing these key sites— by incentivizing a mix of uses—would generate new jobs and tax revenue for the City, improve aesthetics, safety, accessibility, and micro-mobility improvements.

In October 2012, Superstorm Sandy made landfall. While the City of Long Beach has, historically, faced damaging winds, repetitive flooding, and storm surge, Superstorm Sandy was the largest storm in

New York State’s recorded history, devastating Long Beach, causing damage to homes, businesses, and key infrastructure, just as the economy was beginning to recover from the recession of 2008. The City was completely inundated by the storm, from the ocean and bay. In the immediate aftermath, the City focused its attention on recovery efforts to ensure that critical infrastructure and emergency services were operational and able to serve residents. Since then, Long Beach officials have focused their attention and resources on resiliency, sustainability, and flood mitigation measures. The City has incorporated sustainability into all capital and operational considerations, reinforcing the City’s ability to recover, as well as remain operational and economically fortified during and after storm events.

Incorporated as a city on June 1, 1922, Long Beach has a long planning history. This section summarizes the recommendations made and status of some of the City’s previous planning initiatives. It is appropriate that on the heels of celebrating its centennial in 2022, the City will look to this document to chart the course into a new century.

The City of Long Beach has a long history of planning for its future by learning from its past, assertively responding to its current challenges and engaging with residents, visitors, and business owners. The City has implemented many recommendations presented in its long-range planning documents, including zoning code amendments, open space preservation, resilience planning, streetscape and safety improvements via Complete Streets policies and economic development initiatives, and pursuit of grant funds.

Although diverse in their content, many of the previously completed studies, plans and reports reverberate similar visions and goals and in doing so, have guided the City’s decision making. One

goal contained in just about every plan and study is achieving the precarious balance between the beauty and benefit of the City’s waterfront with the impacts of flooding, underscoring the importance of the City’s long-term commitment to implementing resiliency measures that reduce the risk to City residents and their property. The vision and goals of these past plans, studies, and reports are carried forward into this Comprehensive Plan.

The Downtown Long Beach Economic Development Plan was prepared in a collaborative effort between the City Council and the Economic Development Committee of the Long Beach Island Neighborhood Advisory Council. The purpose of the study was to evaluate retail activity in the City’s Central Business District (CBD) via a survey of commercial/retail owners, residents, and visitors. The study analyzed factors that affect commercial health, including the retail mix, available parking and public transportation, urban design, and cultural and event space. The Economic Development Plan identified potential for capturing additional retail expenditures with new mixed-use development in the CBD by implementing the following key initiatives:

f Programming Kennedy Plaza to be the heart of a thriving downtown, with events such as Arts in the Plaza and a Farmers’ Market;

f Working with Waldbaums (now Stop & Shop) to redesign their shopping center;

f Attracting new anchor tenants, including a catering hall, a Cineplex, and the post office expansion;

f Creating a Business Improvement District (BID);

f Enforcing parking regulations;

f Expanding and improving non-vehicular transportation options (such as a trolley); and

f Continuing to improve pedestrian environment with plantings, benches, traffic calming measures at intersections, safer crosswalks, and other streetscape initiatives.

Though prepared in 1997, this Economic Development Plan was prescient in its focus and recommendations. Many of the issues documented in the 1997 Plan were reiterated in responses to the current survey, in discussions with City of Long Beach residents and stakeholders, and remain as priority action items presented in this Comprehensive Plan.

The 2007 Comprehensive Plan is the City’s most recently adopted Comprehensive Plan. The 2007 Plan carried forward economic development recommendations presented in the Downtown Long Beach Economic Development Plan (1997), including the redesign/revitalization of the Stop & Shop plaza and the City’s downtown and existing commercial centers. The 2007 Plan described necessary infrastructure improvements for roadways and sidewalks, wastewater collection and treatment systems, storm water management, and waterfront revitalization; all front and center in the New York Rising Community Reconstruction Plan (2014). The Plan also described necessary traffic, roadway safety, transportation, and multimodal improvements. Several of these recommendations were codified in the City of Long Beach Complete Streets Policy (2013) and subsequently implemented via grant-funded projects in 2015 and 2016 and remain a priority goal for the City. The 2007 Plan recommended amending the City’s zoning code to facilitate workforce housing by allowing new uses in the City’s business district. While the City has allowed some housing, the zoning does not currently allow mixed-use developments in the Park Avenue business district. Amending the

Zoning Code to allow housing over commercial/retail properties, where appropriate, and many of the other recommendations of the 2007 Comprehensive Plan remain relevant and are carried forward into this updated Plan.

The City’s BOA Pre-Nomination Study focused on the North Park neighborhood, which is bounded by Magnolia Boulevard to the west, Long Beach Boulevard to the east, Reynolds Channel to the north, and Park Avenue to the south.

The BOA Study sought improvements in four major areas: business and job development, housing, recreation and open space, and infrastructure. Business and job development intends to provide a wider range of jobs with a focus on career training, provide local hiring opportunities for redevelopment projects, while continuing to provide diverse retail options. For housing, the BOA study seeks to utilize traditional and innovative planning strategies to provide diverse housing options, with an affordable component that is responsive to the existing neighborhood context. Recreation and Open Space recommendations include both new and expanded community facilities designed to provide recreational

and educational opportunities for the community, children in particular. Infrastructure recommendations include a focus on preserving existing housing stock and flood mitigation.

The BOA study area includes residential, recreational, commercial, industrial, and community land uses. Residential uses are clustered in the center of the BOA, while the boundary consists primarily of commercial uses. Recreation, industrial, and community uses are dispersed throughout the area.

The City continues to pursue grant funding for Phase II; however, these opportunities, when offered, have been highly competitive and otherwise limited by New York State.

In 2013, the City Council adopted a Complete Streets policy to advance mobility, safety, and connectivity within and between the City’s neighborhoods. Complete Streets are roadways designed for safe, convenient pedestrian, motorized and nonmotorized transportation access and mobility for all roadway users. The policy recommends specific phased measures to increase pedestrian connectivity and non-motorized transportation, as well as construct crosswalks, curb extensions, and

other pedestrian safety improvements. Since the Complete Streets policy was adopted, the City has required implementation of these improvements wherever possible. The City has received $7 million in grant and City Capital Plan funding that has paid for a variety of improvements, including bicycle lanes, permeable pavement utility strips, streetlights, improved crosswalks, curb extensions, streetscape improvements (including sidewalk planters and bicycle racks), and other safety upgrades on Edwards and National Boulevards. Design work is in progress for an additional $2.5 million of improvements on Park Avenue, including: gateway and streetscape enhancements, traffic calming measures, and connectivity projects within the Bayfront and on Long Beach Boulevard.

Comprehensive Plan Update – “Creating Resilience: A Planning Initiative” (2018–Draft)

In response to, and to rebuild from, Superstorm Sandy (2012) and the subsequent economic recession, in 2015 the City of Long Beach initiated a Comprehensive Plan Update. The Plan Update was organized around four topics:

f Environmental Resilience addressed infrastructure resilience and sustainability, including storm water management, water quality, protection

strategies for and necessary upgrades to critical infrastructure, residential and commercial development along the ocean and the bay, renewable and energy-efficiency programs, sea level rise, climate change, and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

f A Productive and Sustainable Economy assessed economic development, land use, zoning and housing trends, neighborhood preservation, streetscape, recreation, and gateway improvements. The Plan Update recommended a focus on economic development initiatives within the CBD, Bayfront, Oceanfront, and West End neighborhoods, and along Long Beach Boulevard.

f Transportation and Mobility focused on improving vehicular circulation and relieving traffic congestion via a range of parking management strategies. This section recommended enhancing transit and multimodal connections throughout the City through the Complete Streets Policy.

f Implementation and Phasing provided a timeline for future initiatives, and a general discussion of funding sources.

Though this Plan was not adopted by the City, its focus on balancing transportation, infrastructure, housing,

and land use pressures with economic development, environmental sustainability, and resilience remain relevant.

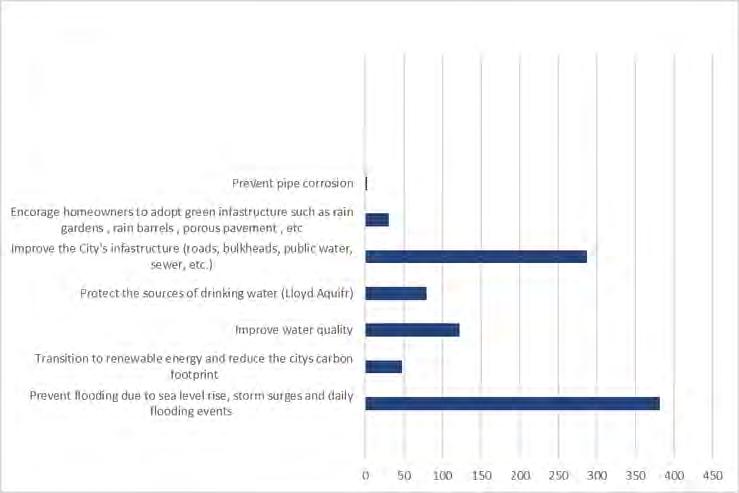

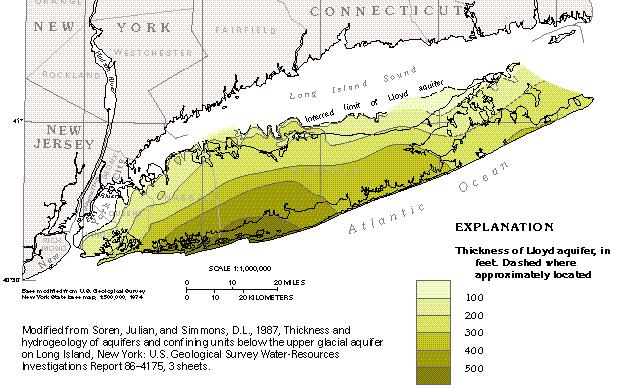

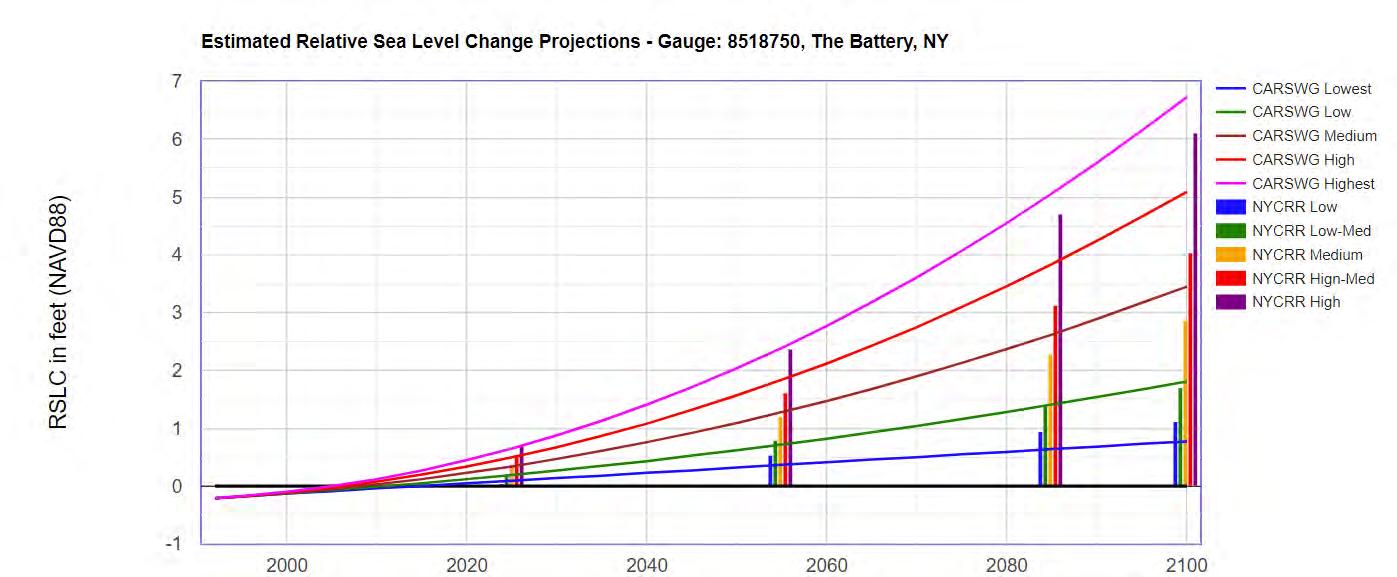

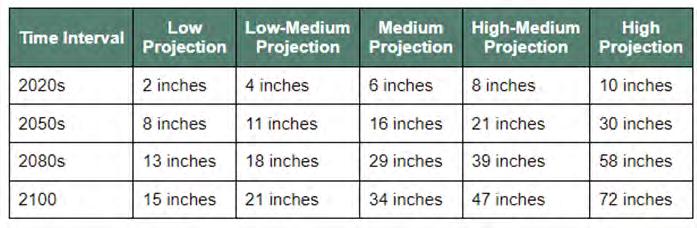

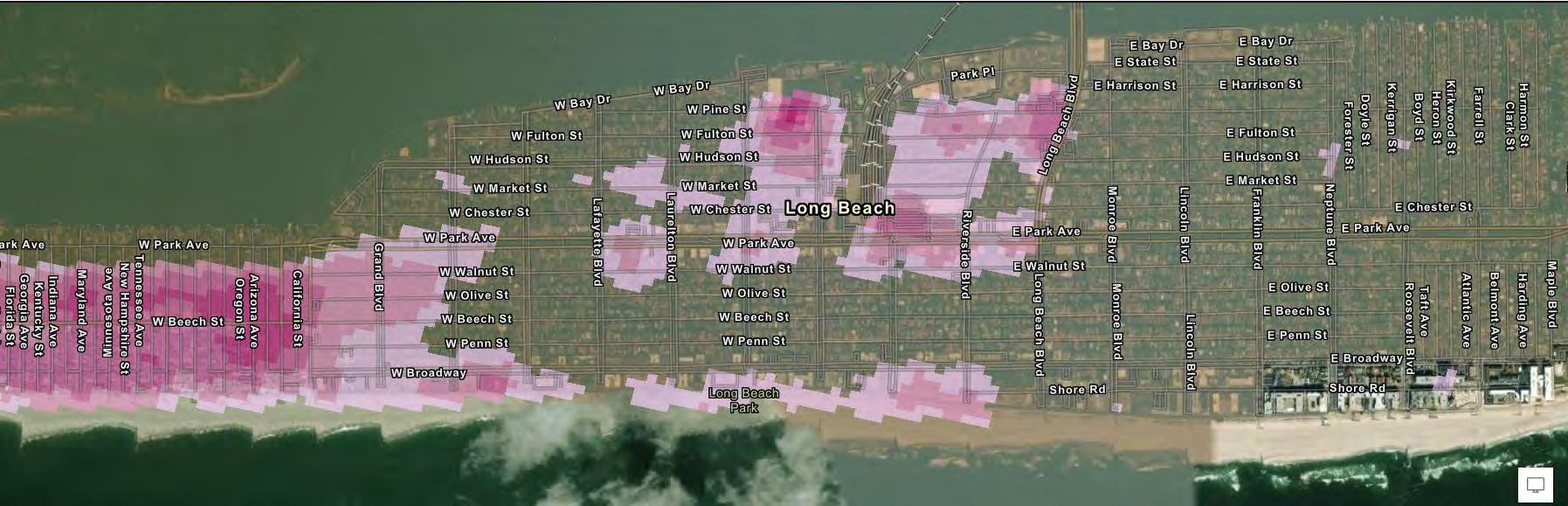

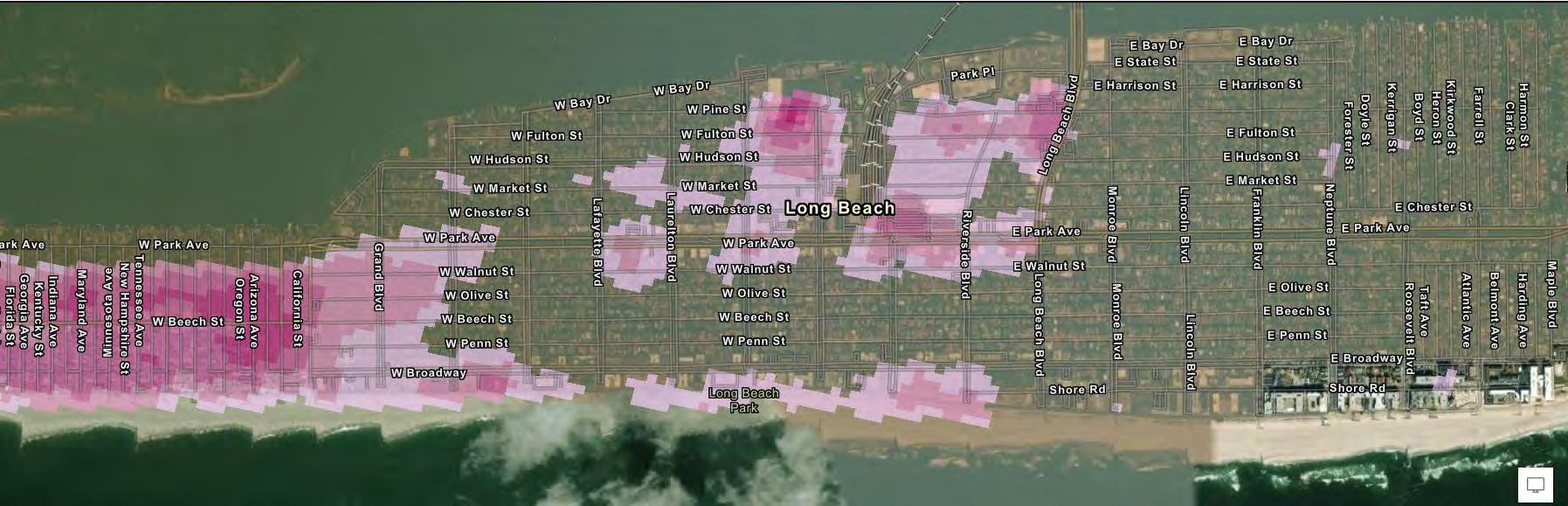

One of the most significant challenges to the longterm sustainability of the City of Long Beach is sea level rise and more frequent short-duration high-intensity storm events. Born from its oceanfront location on an Atlantic Coast barrier island, development density, high water table, and low permeability, Long Beach has long prioritized community resilience. When faced with a natural disaster and/or extreme weather event, a community’s preparedness is exposed. A resilient community is not only prepared to withstand and respond to a natural disaster, but also able to rebound and recover quickly and efficiently. The following planning documents summarize Long Beach’s long commitment to fortifying its position. However, as demonstrated in and documented by the City’s New York Rising Community Reconstruction Plan (2014), even the best laid plans can be tested during a catastrophic event. In the years following Superstorm Sandy, the City has identified its vulnerabilities and allocated resources toward community resilience.

Prompted by the passage of, and to ensure consistency with, the City’s Comprehensive Plan adopted in 2007, the City of Long Beach prepared a Draft Local Waterfront Revitalization Plan (LWRP) in 2009. While the 2009 Draft LWRP was ultimately not adopted by the New York State Department State (DOS), it reiterated recommendations prioritized in the 2007 Comprehensive Plan. The 2009 Draft LWRP recommended economic development and revitalization of the Bayfront area with a mix of residential, commercial, civic, and water-dependent uses. To facilitate the redevelopment of this area, the 2009 Draft LWRP recommended land use and zoning text and map amendments for a mix of uses along the waterfront. Other familiar priorities described in the 2009 Draft LWRP included design development of the Stop & Shop plaza, streetscape/ façade improvement projects, fortifying flood and erosion control infrastructure, as well as increasing public access to and pedestrian amenities along the waterfront, including recreation and open space opportunities, boardwalks and walkways, docks, and piers. The Plan also promoted improved pedestrian connectivity and support for non-motorized transit.

In 2016, and generally in conjunction with its comprehensive planning initiative at that time, the City completed a Draft LWRP. The Draft was submitted to and reviewed by DOS, with their comments being given to the City in 2018. As DOS requirements had changed significantly in those two years, funds were obtained from DOS to make the necessary revisions. The City is incorporating DOS’ comments on the 2016 Draft LWRP and coordinating with this Comprehensive Plan to ensure consistency of recommendations. The City intends to complete this effort in 2024 then submit the final Draft LWRP to DOS. Priority initiatives detailed in the 2016 Draft LWRP that continue to be relevant include: implementation of multimodal safety projects detailed in the City’s Complete Streets policy (along Long Beach Road and Park Avenue), including sidewalks, bicycle lanes, traffic calming measures, streetscape improvements, streetlights, and crosswalks.

Another important component of the City’s postSuperstorm Sandy resilience efforts involved a sustainability assessment for the West End neighborhood. The assessment evaluated existing conditions, identified short- and long-term

opportunities for improving environmental, economic, and social sustainability. Through desktop analyses, physical condition evaluation, stakeholder interviews, a photographic inventory, and site visits, the assessment cataloged positive qualities and areas for improvement. The evaluation was accomplished using the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Neighborhood Development (ND) Sustainable Neighborhood Assessment Tool.

The assessment recommended policy, planning, and development initiatives that, when implemented, would reduce the City’s disaster risk and create a more resilient and sustainable future. The recommendations were divided into five key themes, which are common throughout many of the planning documents summarized herein. These are:

f Living with Water – The West End neighborhood is built in a low-lying area with very little permeable surface and a high water table. Climate change models demonstrate that over the next 100 years, extreme weather events and storm flooding will become far more frequent. To be best prepared, the City must implement measures that help the West End neighborhood adapt to, and rebound from, the consequences of major storm events.

f Green Space/Active Space – The assessment revealed an “overwhelming” lack of open space in the West End neighborhood. In addition to the benefits offered by connecting the ocean and bay sides of the neighborhood, passive and generally undeveloped recreation areas and open spaces absorb storm water.

f Rebranding and Reinvesting – The assessment highlighted the importance in continued investment in the West End neighborhood, noting that capital investment “improves economic vitality by attracting residents and visitors, helps foster an identity for the neighborhood and creates a business environment that invites and encourages a diverse mix of offerings.”

f Cyclist and Pedestrian Infrastructure – The physical constraints and lack of pedestrian, non-motorized amenities in the West End neighborhood have resulted in congested streets and significant parking supply-and-demand imbalances. The assessment recommends physical and policy changes to address this disparity.

f Parking Management – Implementing a parking management strategy would allow creative off-street shared parking arrangements to

accommodate not only the existing residential population, but also the commercial/restaurant/ retail demand and maximize parking efficiency.

In October 2012, Superstorm Sandy completely inundated the City of Long Beach with water from the Atlantic Ocean on one side of the barrier island, and storm surge from the Bayfront. The storm caused power outages, damage to homes and businesses, and a complete shutdown of the City’s drinking water supply and sewer infrastructure. Given the extent of destruction, the City of Long Beach, Nassau County, New York State, and many federal government agencies evaluated the damage, issued reports documenting the physical condition and estimating financial damages to the City of Long Beach. The NYRCR Plan is one of those reports.

The NYRCR Program was created in 2013 by the Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery (GOSR) to provide financial assistance to communities throughout New York State that were hardest hit by Superstorm Sandy.

Using U.S. Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Disaster Recovery (DR) funding, the NYRCR Program provided technical assistance to municipalities to inventory

damage and develop projects that would increase the communities’ resilience to storm events. Following completion of the NYRCR Plan, GOSR selected projects that would receive funds for implementation. GOSR initially allocated $25 million to the City of Long Beach for implementation of resiliency projects. To date, the City has received approximately $20 million for projects under the NYRCR Program and has supplemented the funding with Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and City Capital Projects dollars. A list of these projects is provided in Appendix C. Some of the most significant City projects and their status as of May 2023 are:

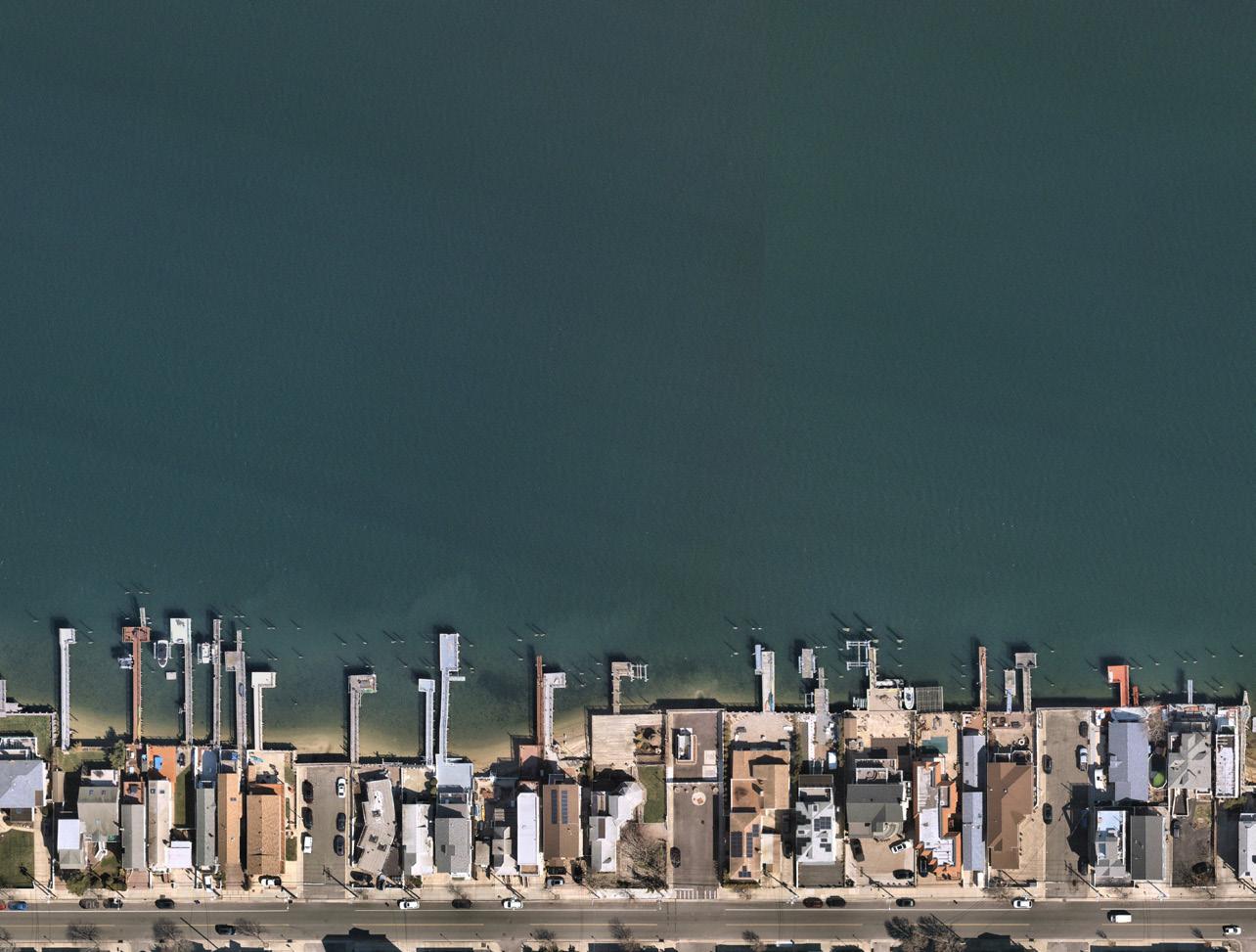

f North Shore Bulkheading project – Construction of new and/or fortification of existing bulkheading along the City’s north shore. All new bulkheads were installed to the height equal to the Base Flood Elevation (BFE).

f Northshore Critical Infrastructure Project –Funded by FEMA, this project is underway and will provide bulkhead improvements and pumping of water during high tides and flood events.

f Office of Emergency Management – Completed construction of the Office of Emergency

Management within the sixth floor of Long Beach City Hall.

f Long Beach Drainage Improvements –Addresses chronic flood prone areas in Long Beach. Improvements include concrete curbs and gutters, sidewalks, pedestrian ramps and crosswalks, driveway aprons, street lighting, and the installation of a completely new subsurface storm sewer drainage system to mitigate potential flooding.

f Consolidation of the Sewerage Treatment Plant with Nassau County – Results in the cleanup of Reynolds Channel, improves the wetland protection for future storms, and ultimately frees up an approximately five-acre parcel for redevelopment/reuse by the City.

f Citywide infrastructure improvements –Completed the installation of new catch basins and manholes, and installing backflow devices in key locations.

f Critical Services – Fortifying emergency service structures (Fire Stations and Police headquarters) by raising electrical panels, flood- and windproofing windows and doors and installing fixed generators. This project is funded by FEMA.

In 2019, recognizing there is no one solution for mitigating flood hazards, the City prepared a Floodplain Management Plan (FMP) to identify alternatives that would increase flood resilience. The first FMP was developed in 2019, adopted in 2020, and is in the process of being adopted. The Committee meets several times a year to discuss flooding issues and potential improvements that could be included in the next FMP update.

Through a community engagement process facilitated by the City, the FMP identified areas of repetitive loss (the entirety of the City) and initiatives to meet flood hazard mitigation objectives.

The FMP meets City, State, and Federal planning requirements that allow the City to remain in the Community Rating System (CRS) program with a Class 7 CRS Rating. This rating reduces homeowners FEMA flood insurance by 15 percent. The City is actively implementing methods and activities with the goals of maintaining this rating and working to lower it. If the rating is lowered, then flood insurance would be reduced even more. The City’s goal is to obtain Class 6 or lower status, resulting in a 20 percent insurance reduction

The FMP also coordinates existing plans and programs for high-priority initiatives and projects to mitigate possible disaster impacts. The FMP is linked to plans adopted by the City and Nassau County to ensure they can work together in achieving hazard mitigation.

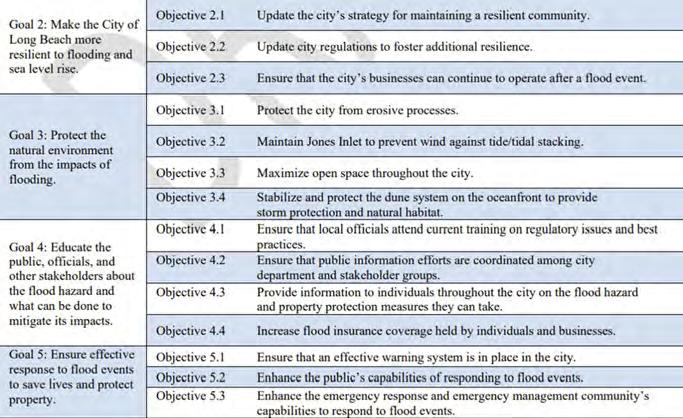

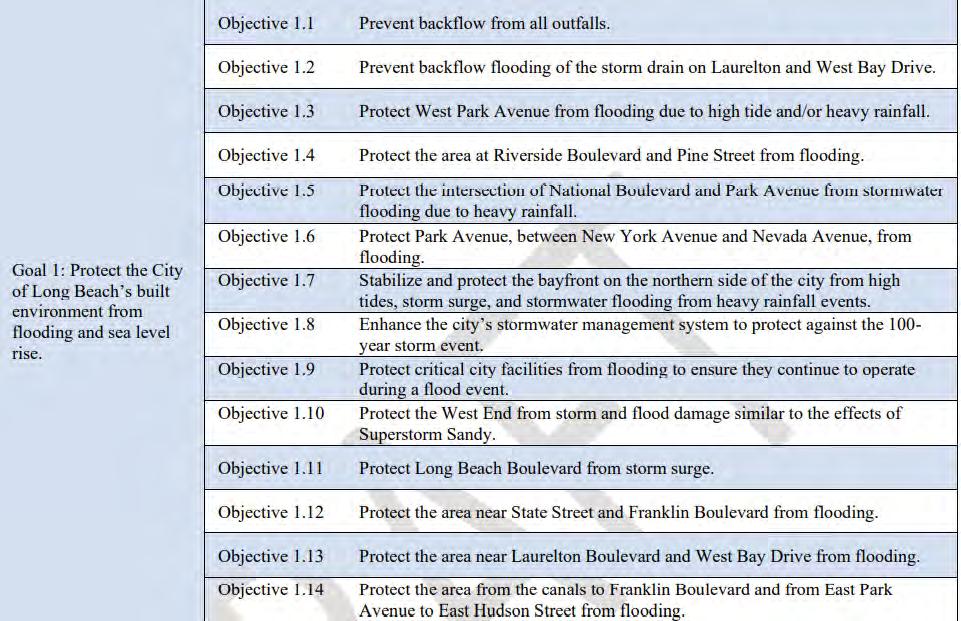

The FMP features five goals to protect the City from flood vulnerability:

f Protect the City’s built environment from flooding and sea level rise;

f Increase resiliency to flooding and sea level rise;

f Protect the natural environment from the impacts of flooding;

f Educate the public, officials, and other stakeholders about flood hazards and what can be done to mitigate impacts; and

f Ensure effective response to flood events to save lives and protect property.

The objectives under each goal lay out steps the City can implement to reduce their risk and vulnerability to flooding.

The process to develop a Comprehensive Plan involves reviewing past planning efforts and documents, assessing current conditions and trends, and developing reasonable goals and strategies while engaging the community in a dialogue about its current and future wants and needs (see Figure 2-1, Comprehensive Plan Process). The planning process for the City of Long Beach Comprehensive Plan

began in late 2021 with the selection of a Consultant Team and formation of an internal working group to assist with the endeavor. Shortly thereafter, the working group prepared a Community Engagement Plan, which included community leader interviews, a community-wide survey, public workshops, open houses, and regular consultations with the City’s Planning Advisory Board (PAB). The PAB served an important role in the process by identifying community champions, reviewing data, identifying priorities, and

assisting with setting the direction for the Plan. The components of the community engagement efforts are discussed in more detail in this chapter.

The City of Long Beach PAB was established in late 2020. The 11-member board is appointed by the City Manager and is tasked with the following duties and functions:1

f To study, report, and recommend to the Department of Economic Development and Planning2 by the City Council or City Manager;

f To promote public interest and understanding in the physical development of the City of Long Beach and in all matters falling within the authority of Department of Economic Development and Planning;2 and

f To meet not less than once a month and at such other times as called for by the director of the Department of Economic Development and Planning2 in order to keep record of its activities and meetings resolutions findings and determinations.

1 https://www.longbeachny.gov

2 aka Department of City Planning and Development

The PAB held six (6) [February, March, May, November, December, and January/February] formal meetings during Plan development, and the PAB members were active in support of the public meeting. In addition, City staff communicated regularly with the PAB to update the Board on the process, progress, and broader community engagement efforts. The PAB has and will continue to serve as the primary community champion for the Plan, assisting City staff by promoting community engagement activities.

Between January and March 2022, the Consultant Team met with more than 30 community leaders to introduce the Comprehensive Plan development process and gain early insight into issues facing the City. The results of these conversations guided the next stages of the community engagement process including identifying questions for the community survey and ideas for exploration at communitywide workshops and meetings. Some community leaders became community champions for the Plan development.

The Consultant Team developed an interactive project website and StoryMap that served as the primary online information resource for the project. The StoryMap supplied background information for the Comprehensive Plan, notifications on community engagement activities, and hosted the online community survey. The StoryMap was accessed through the City’s website and was active from April 2022 through the adoption of the Plan.

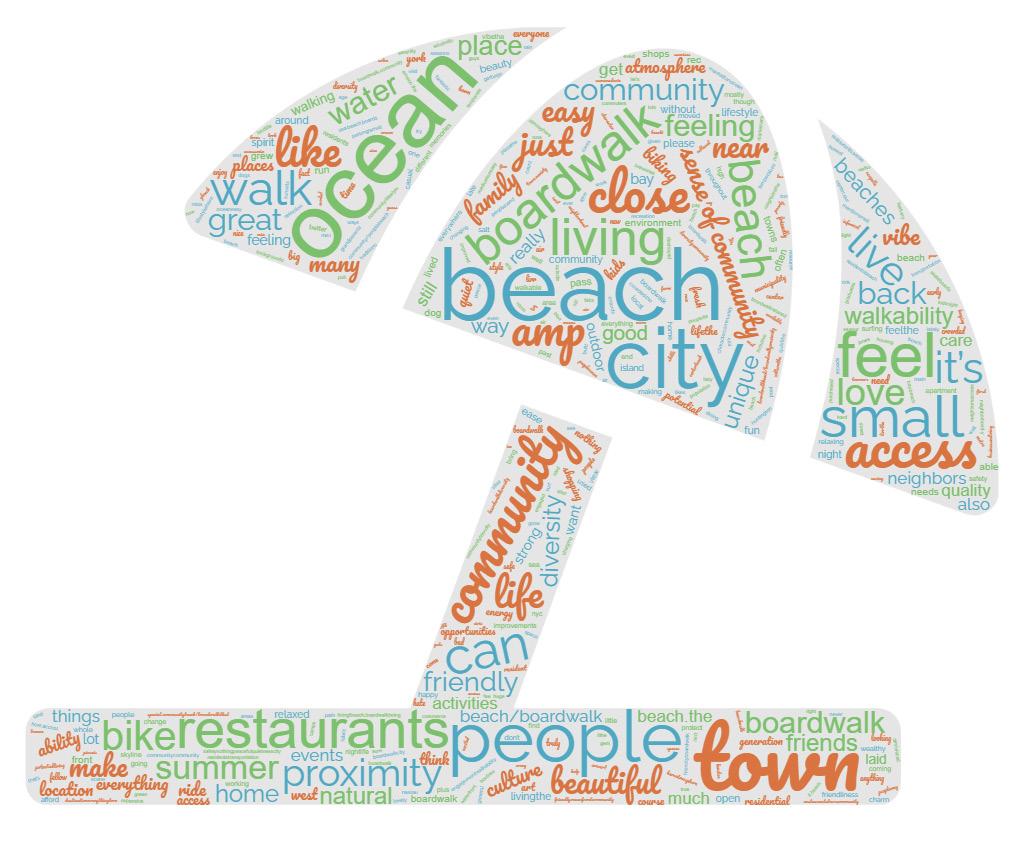

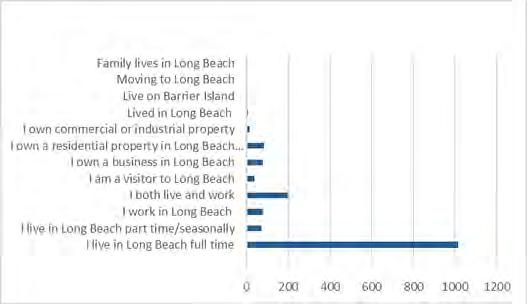

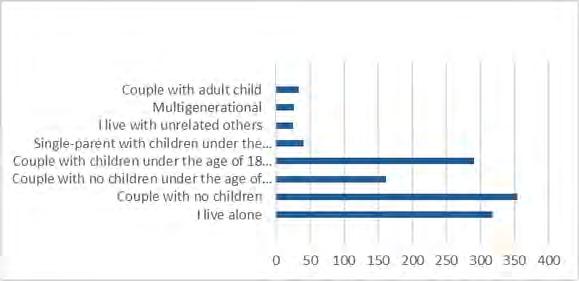

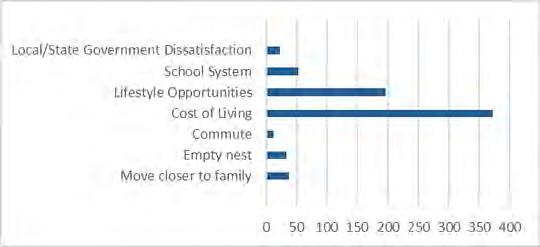

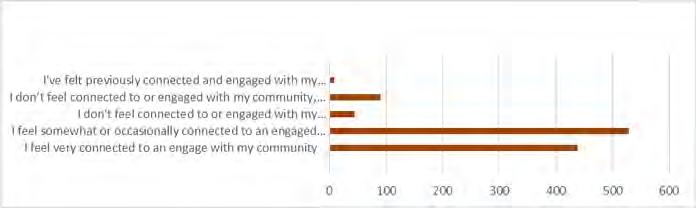

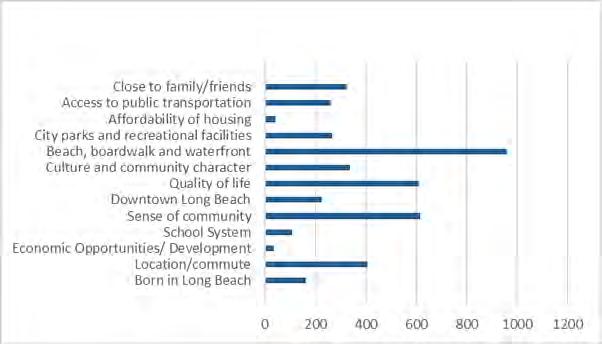

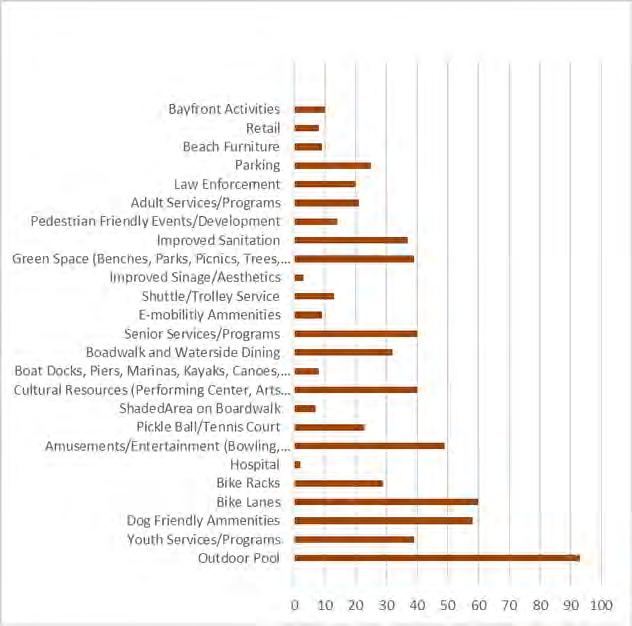

To engage and draw upon the knowledge and priorities of the residents and business owners, a community-wide survey was developed and conducted from April through July 2022, both online and in person, with paper copies distributed through community organizations. The survey received approximately 1,200 responses from a wide cross section of residents. While the survey recorded a variety of concerns, needs and ideas, results revealed 73 percent of respondents rated the overall quality of life in the City as good or excellent. Other key findings include:

f More than 90 percent of survey respondents noted the beach, boardwalk, waterfront as the main reason they choose to live/work in Long Beach.

f Approximately 40 percent of survey respondents identified improving roadways, drainage, utilities, and other infrastructure as priority projects.

f Approximately 50 percent of survey respondents noted there is not enough affordable senior housing in Long beach.

f Seventy percent of respondents don’t feel comfortable biking on Park Avenue.

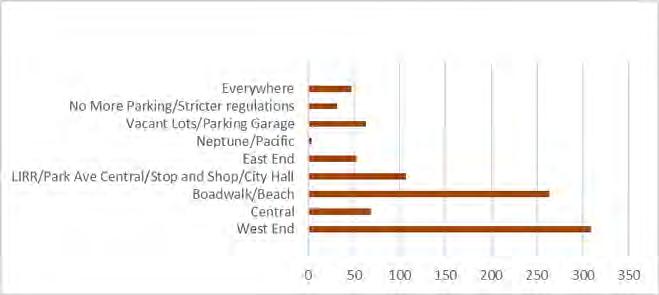

f Approximately 90 percent of survey respondents indicated parking is challenging in the West End Business District.

f Sixty-one percent of respondents agreed that the City should develop vacant parcels along the Bayfront.

Specific suggestions received from residents in the survey were considered during the development of the Plan’s Goals and Strategies, and, in many cases, ideas were combined and generalized to allow for the greatest flexibility. A report summarizing the community survey results is included in Appendix D.

The kickoff community-wide event for the Comprehensive Plan was an informational Virtual Public Meeting held on April 21, 2022; the link to this meeting was posted on the StoryMap webpage. The focus of this public meeting was to introduce the Project Team, explain the intent for and use of a Comprehensive Plan, review the process and timeframe, discuss the data and components that would be included in the final Plan, and to answer questions related to the Plan and its development.

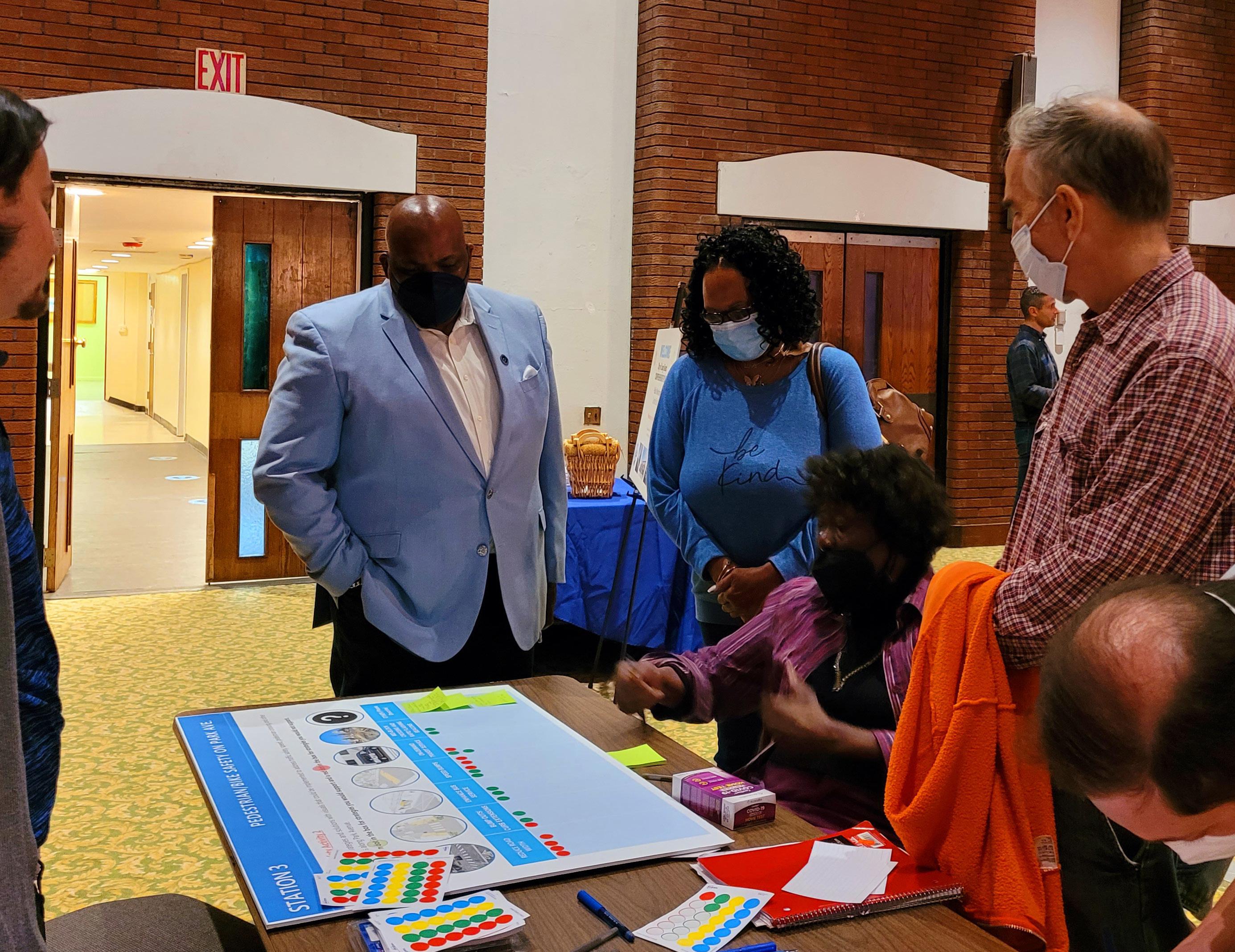

The second series of community engagement events included in-person public workshops and community meetings held between May and August 2022. Each event had a specific targeted set of objectives as described and summarized herein.

May 2022 Neighborhood Workshops. In May 2022, three (3) neighborhood workshops were held. The first two workshops were held on May 19—one in the West End neighborhood and the other in Central/ East End neighborhood. A third workshop was held on May 23 in the North Park neighborhood. Each workshop was organized in two parts: part one included a brief presentation on the process and an overview of survey results received to date (through

May 15), with a focus on the results from respondents in the associated neighborhoods; part two included interactive exercises on select topics areas based on emerging subject themes identified through initial survey results for the various neighborhoods or as identified by community leaders.

f The West End workshop included interactive exercises on parking and circulation, climate resiliency, and quality of life.

f The Central/East End workshop included interactive exercises on opportunity sites adjacent to the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR), transit oriented development, and pedestrian/bike/traffic safety.

f The North Park workshop included interactive exercises on opportunity sites along the Bayfront, housing affordability, and other areas of interest.

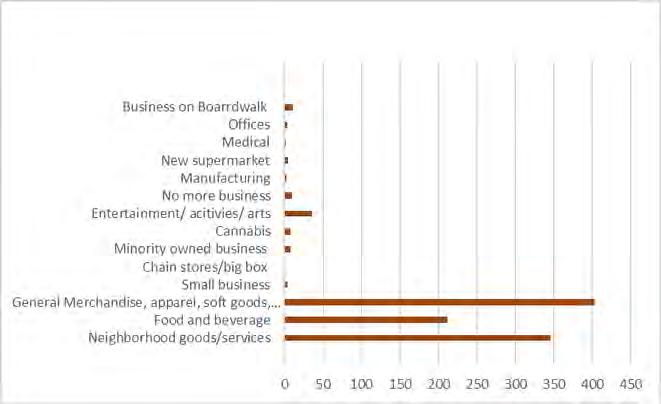

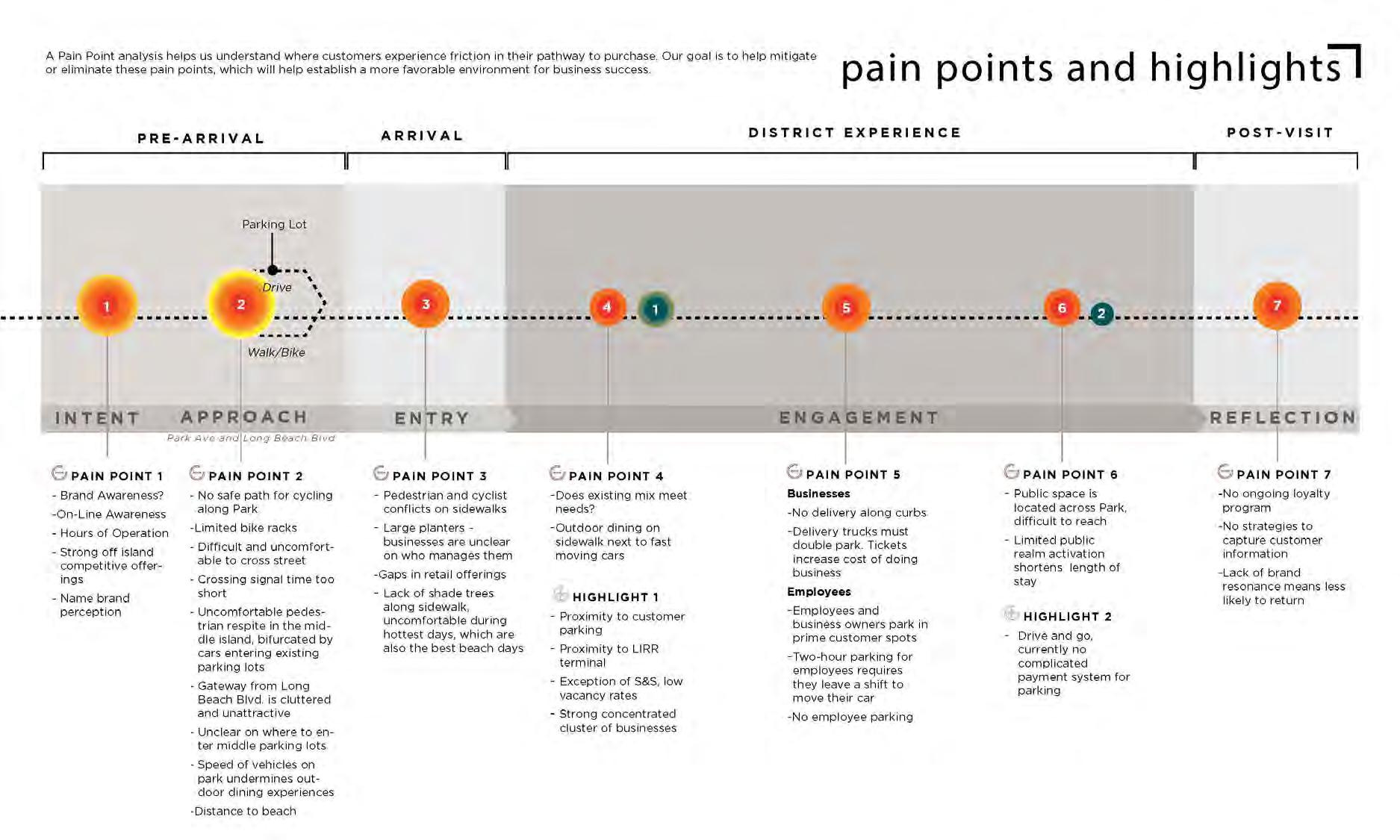

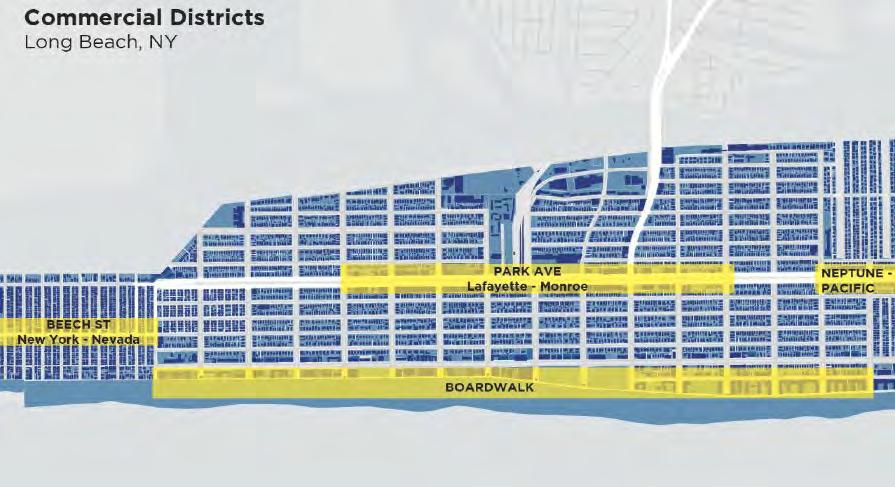

June 2022 Commercial District Workshop. The Consultant Team’s economic development specialist, Streetsense, focused on the City’s commercial corridors and market conditions. Specifically, tasks for Streetsense included review of economic development, physical assessment, market demand, and capacity for the Central Business District along Park Avenue, West End Business Districts along Beech Street, the Boardwalk, the City entry area

along Long Beach Boulevard, and East Park Avenue between Neptune and Pacific Avenues. A commercial district workshop was held on June 2, 2022, and the Consultant Team reviewed their findings with residents and business owners.

August 2022: Chamber Meeting. This Chamber of Commerce sponsored meeting was conducted via a virtual platform (Zoom) and in-person. City staff presented an overview of Plan goals, objectives, and progress to date followed by a question-and-answer session. Meeting attendees were also encouraged to submit written follow-up questions.

Early December 2022: PAB meeting and Review. In early and mid-December, the Project Team and City Staff met twice with the PAB. At the first meeting in early December, the Project Team updated the PAB regarding the Plan process and timeline and presented the Plan’s proposed general themes and strategies. The PAB subsequently received the full draft Comprehensive Plan for their review and comment. In mid-December, the Project Team and City Staff met with the PAB to review the overall draft Comprehensive Plan.

June 2023: Public Open Houses. In June 2023, the Project Team conducted two community engagement sessions (June 14 at the Long Beach Martin Luther King Center and June 15 at Long Beach City Hall) to present the final draft Comprehensive Plan. Together with City Staff, the Project Team presented the Plan’s goals, strategies, and implementation schedule. Workshop attendees were asked to comment on and prioritize draft goals and strategies that best aligned with their preferences. Following the engagement meetings, the Project Team and City Staff reviewed community feedback and noted significant similarities with priorities expressed in the Community Survey conducted more than a year prior. Community feedback was integrated into the final draft Comprehensive Plan presented for community consideration at the City Council’s subsequent Public Hearing.

Summer 2023: State Environmental Quality Review, Mandatory Referrals, and Comment Period. Pursuant to Title 6 NYCRR Part 617 of the implementing regulations pertaining to Article 8 of the Environmental Conservation Law, the adoption of a Comprehensive Plan is a State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA) Type 1 Action (6 NYCRR, Part

617.4). By Resolution issued on June 6, 2023, the Long Beach City Council declared themselves SEQRA Lead Agency for the environmental review of the City of Long Beach Comprehensive Plan. Also, by resolution issued on June 6, 2023, the City Council scheduled a Public Hearing on the draft City of Long Beach Comprehensive Plan for June 20, 2023, establishing a 10-day comment period following the close of the Public Hearing. In addition, per General City Law §28a.6.b and General Municipal Law §239-L&M, the Long Beach City Council referred the City of Long Beach Comprehensive Plan to the Nassau County Planning Commission, which by Resolution No. 10533-23 issued on June 15, 2023, recommended “that the referring agency take action as it deems appropriate, the Commission having no modifications” and offered the following commendation:

“

….The Draft Plan spells out numerous worthy goals and objective [sic] that the Commission strongly supports. Among these are the protection of neighborhoods that would provide a foundation for future zoning amendments; providing a focus on affordable housing, diversification of the housing stock and the preparation of a Citywide Housing Plan; enhancement of mobility and connectivity; enhancement of environment and climate resiliency and the creation of opportunities for sustainable

growth, including creating a TOD district adjacent to the LIRR station, while protecting the unique character of the City’s neighborhoods. The Nassau County Planning Commission will continue to support the City in achieving these goals and objectives and its balanced approach to economic development, sustainability, and the protection of neighborhoods.”

The City prepared a Full Environmental Assessment Form (FEAF) evaluating the potential for the adoption of the City of Long Beach Comprehensive to result in significant adverse environmental impacts. On June 20, the City Council opened and closed a Public Hearing on the draft Comprehensive Plan and collected comments from the community through June 30, 2023. Comments and recommendations collected at community engagement sessions held on June 14 and June 15, and those received subsequent to the City Council’s Public Hearing, were incorporated into the Final 2023 City of Long Beach Comprehensive Plan. By resolution issued on August 1, 2023, the City Council of the City of Long Beach issued a SEQRA Negative Declaration and adopted the City of Long Beach Comprehensive Plan.

The Vision Statement for this Comprehensive Plan was developed using information collected from the online survey, throughout the community engagement process, and via discussions with a broad section of residents, business owners, and community leaders.

We envision a vibrant, inclusive, sustainable community that offers a high-quality of life for all residents and guests. Through responsible planning, we will enhance our infrastructure and public spaces, protect our natural resources, support local business and the arts, and encourage smart economic growth as we work towards a future that is equitable, resilient, and embodies the unique character of Long Beach.

The goals, strategies, and action steps (including citywide, neighborhood, and site-specific action steps) presented in Chapter 4 of this Comprehensive Plan are framed around five (5) theme areas:

Livable Neighborhoods and Sustained Quality of Life, Thriving Places and Robust Year-Round Economy, Access to Mobility and Connectivity, Enhanced Environment and Climate Resilience, Sustainable Growth and Opportunities.

These five (5) themes of the Comprehensive Plan were built from themes that emerged throughout the engagement process:

1. Maintaining and improving the Quality of Life throughout the City and within the City’s residential neighborhoods;

2. Improving roadways, drainage, utilities, and infrastructure within the City;

3. Addressing housing affordability and the need for more housing and medical options for the City’s senior population;

4. Enhancing business districts by increasing the variety of stores and services, improving visual aesthetics, hardscape, and safety;

5. Promoting economic development that encourages a year-round economy;

6. Addressing inadequate parking (especially in the West End neighborhood), transportation, and circulation issues (especially during summer months);

7. Improving pedestrian, biking, and traffic safety throughout the City and especially along Park Avenue;

8. Addressing concerns about climate resiliency and flood risks;

9. Focusing economic development and growth within opportunity sites rather than Citywide or within established neighborhoods; and

10. Capitalizing on the transportation hub of the LIRR along Park Avenue and promoting transit oriented development.

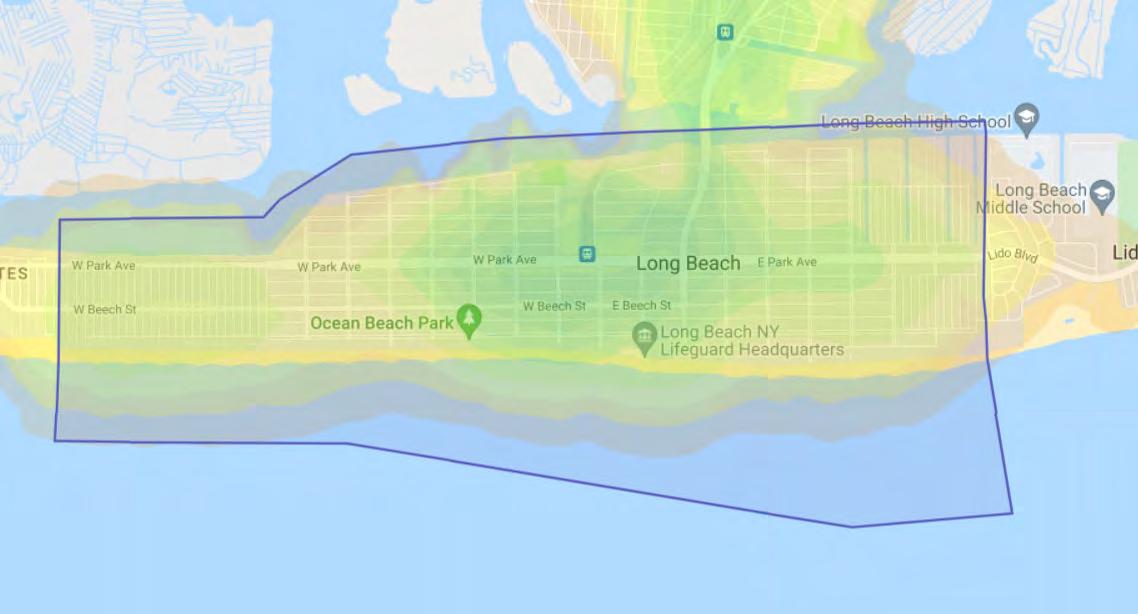

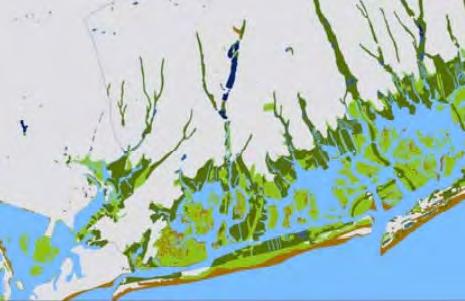

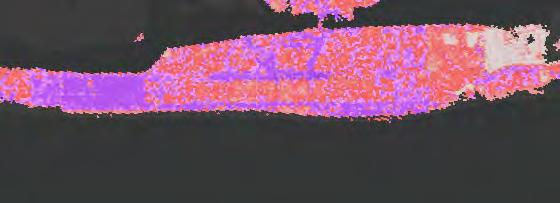

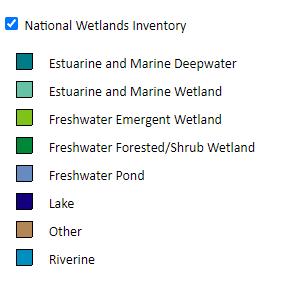

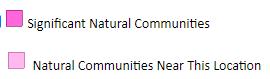

This Chapter provides an inventory, in graphic and tabular format, of the existing conditions in the City of Long Beach’s commercial corridors, transportation systems, community and cultural facilities, and natural resources including climate change and adaptation. This data forms the foundation for the goals, strategies, and recommendations presented in this Comprehensive Plan. The data includes assessments of population and population density, age, race and ethnicity, household, education, and income. Where instructive, the narrative includes trends that can be used to meaningfully plan for the City’s future. For example, where age-related statistics may indicate a steadily aging population, the City could evaluate its existing resources and determine whether additional services may be needed in the future.

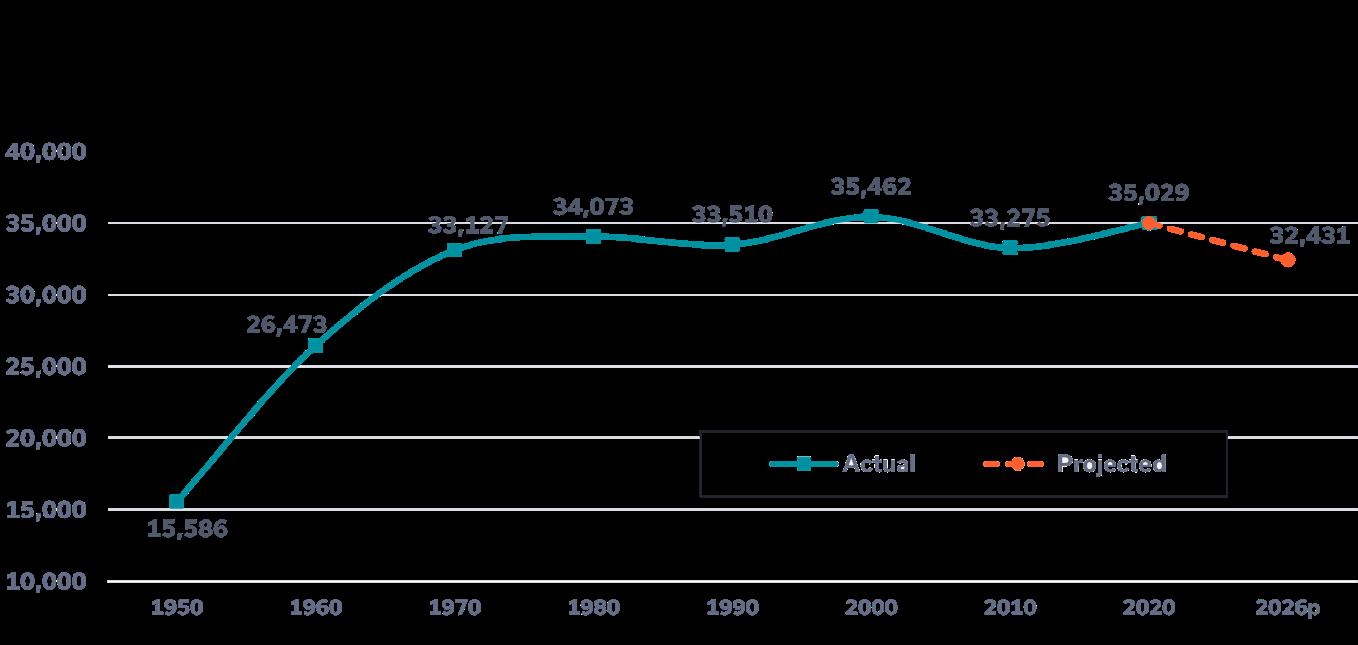

Per the U.S. Census, the 2020 population of the City of Long Beach was 35,029, which represents a slight (five percent) increase from 2010 (33,275). Between 1950 and 1970, the City saw its highest population

growth, with an overall increase of 17,541 (112.5 percent). As shown in Figure 3-1, Historic and Projected Population: 1950–2026, the population has remained relatively constant since 1970, with minor fluctuations over the last fifty years. Specifically, there was a one percent decrease between 2000 and 2020. Projections show an eight percent decrease in City population between 2020 and 2026.1 However, the City has approved approximately 500 new residential units with construction expected by 2026, indicating stabilization and growth. As residents are still returning to rehabilitated homes post-Superstorm Sandy, it is realistic to project a slight growth in population.

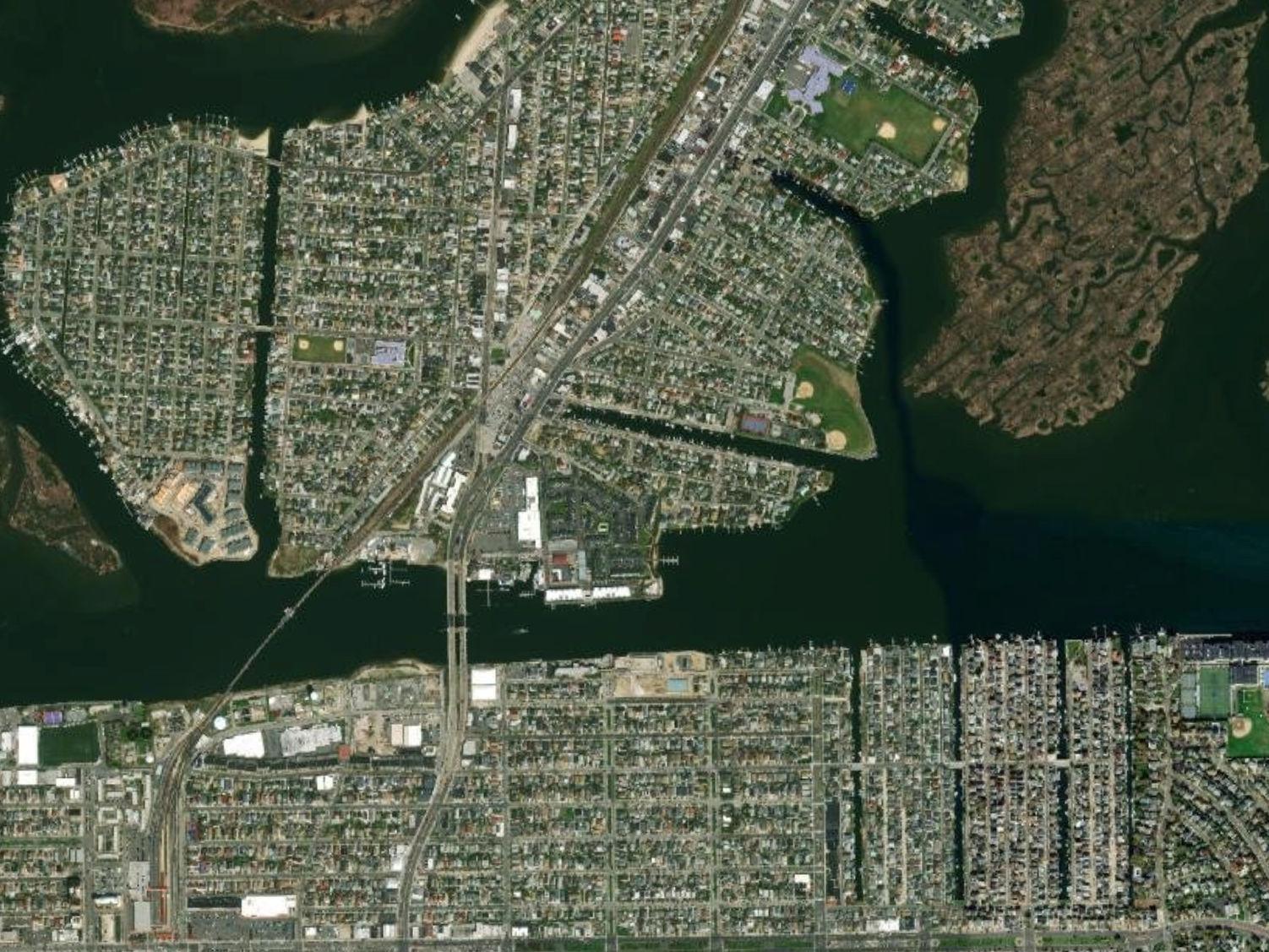

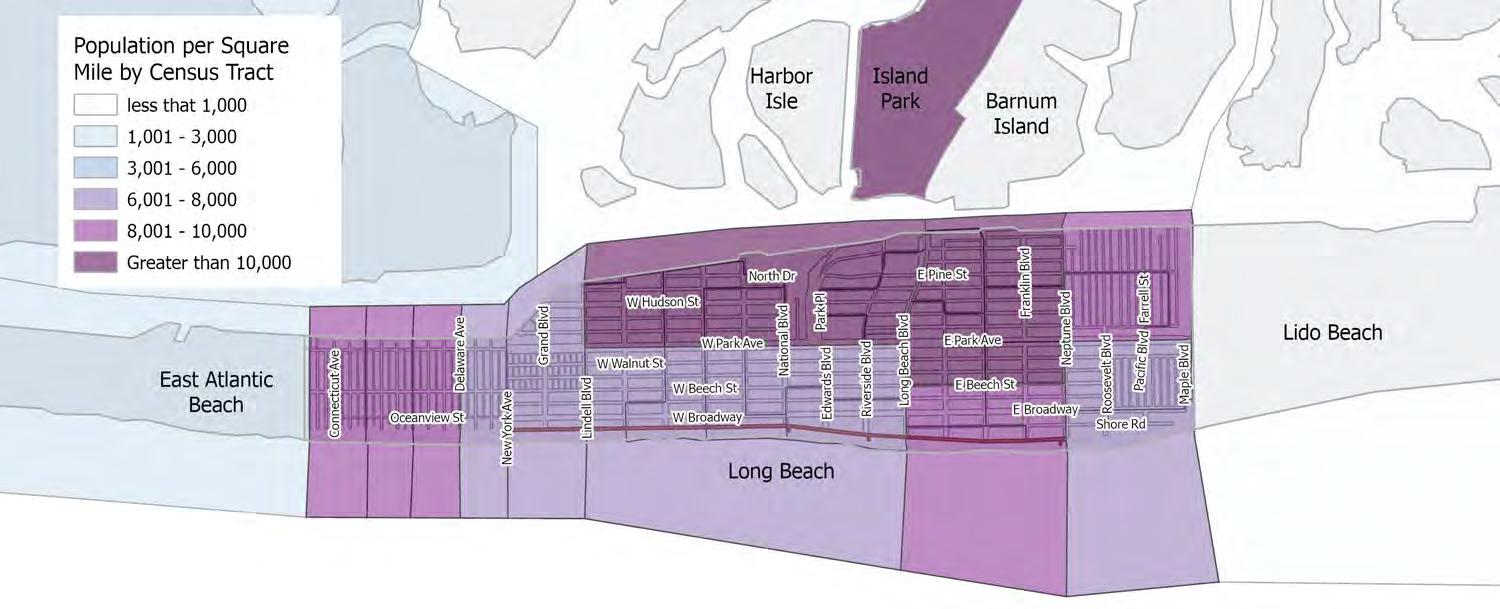

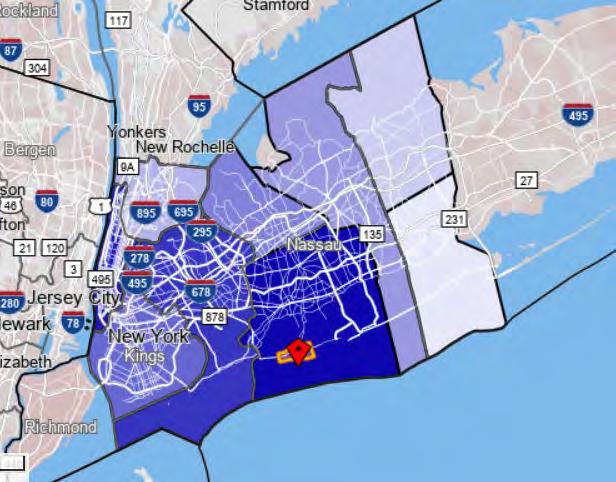

Based on U.S. Census information, at 15,665 persons per square mile (ppsm), the City of Long Beach has a higher population density than its surrounding neighbors and Nassau County (see Figure 3-2, Population Density). Island Park—located to the north of the City on the mainland—has a population density

above 10,000 ppsm but lower than Long Beach, while East Atlantic Beach and Atlantic Beach to the west fall within the 2,000–4,999.9 ppsm census category, and Lido Beach to the east falls within the 50–99.9 ppsm category.

According to 2015-2019 American Community Survey (ACS) estimates, and as shown in Figure 3-3, Median Age Comparison (1990-2019), the median age in Long Beach was 44.9 years old, as compared to Nassau County (41.7) and New York State (38.8). Further review of U.S. Census information indicates that the City’s median age has been consistently increasing since 1990, when the median age in the City was 36.8 years old.

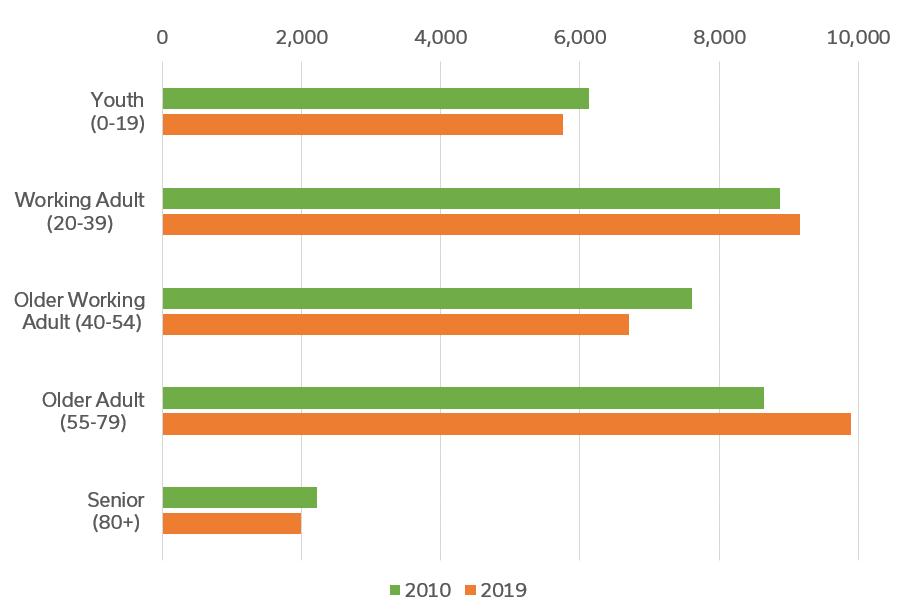

Over the last several decades, the City’s population has been aging, as indicated by the increasing median age. In just the last decade, Long Beach’s older adult population (55–79) grew by 1,252 between 2010–2019 (see Figure 3-4, Population by Age [2010–2019]).

Long Beach may have a larger percentage of older residents than the County as a whole, due to the historic location within the City of in-care facilities that were once hotels converted for this use. The greatest decrease in the age cohort occurred in the older working age adult (40-44)—down 954 persons— and older children (15-19)—down 452 persons— populations. In the 40–54 age population group, data show a decrease of 900 persons between 2010-2019. The data also reflects an increase in the 25-39 age cohort typically comprising young families.

The populations of both Long Beach and Nassau County are diversifying, with the county at-large showing greater diversity. As shown in Table 3-1, Race and Ethnicity, per U.S. Census data, most of the Long Beach population in 2010 was white (75.5 percent), a trend that continued in 2020 with a slight decline (72.9 percent). The second-largest populations for both Long Beach and Nassau County are “Hispanic or Latino.” In Long Beach, specifically, nearly all racial/ ethnic groups have grown since 2010; the African American population, however, decreased by seven percent. As of 2020, 13.4 percent of the Long Beach population is foreign born, adding to the diversity of the City.

Nassau County has seen an 11.2 percent decrease in the white population, while Long Beach’s white population remains stable. Racial groups that saw growth in Long Beach from 2010 to 2020 include “Two or more races” (115.2 percent) and “Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander” (75 percent). The “Hispanic or Latino” population group also grew, from 14.1 percent in 2010 to 15.3 percent in 2020.

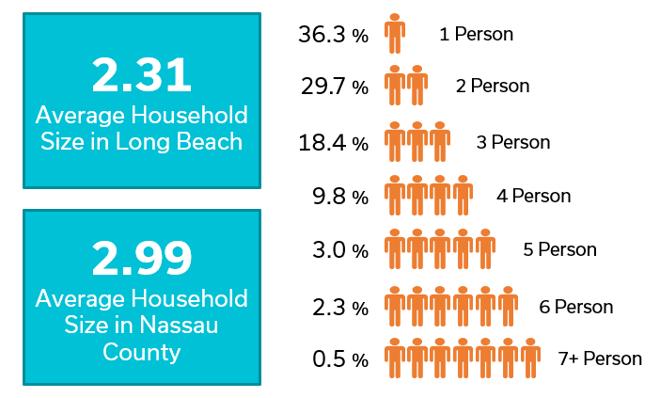

According to 2015-2019 ACS estimates and presented in Figure 3-5, Average Household Size, the average household size for Long Beach increased from 2.18 in 2010 to 2.31 in 2019. Long Beach has a smaller household size when compared to Nassau County (2.99) in 2019. The one-person household is the most prevalent in the City, comprising 36.3 percent of the population, followed by two-person (29.7 percent) and three-person (18.4 percent) households.

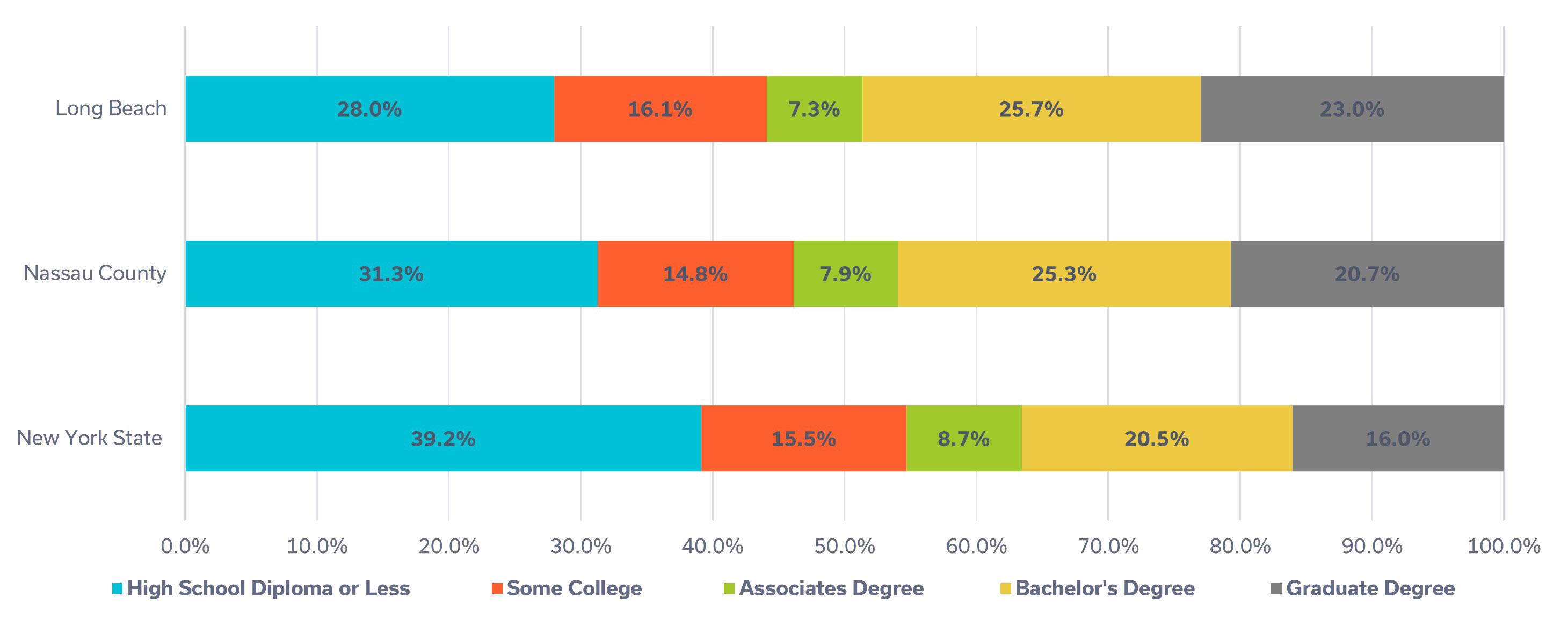

As shown in Figure 3-6, Education Attainment, the City of Long Beach has a high education attainment rate for adults over the age of 25, with nearly half earning an advanced degree (bachelor’s [25.7 percent] and graduate [23 percent]). Nassau County’s higher education attainment rate is essentially the same

S Table 3-1: Race and Ethnicity

as Long Beach, reporting a slightly lower graduate degree attainment (20.7 percent). Per 2015–2019 ACS estimates, when compared to New York State, both Long Beach (48.7 percent total) and Nassau County (46 percent total) surpass the higher education rates for both bachelors and graduate degrees, with New York State reporting 36.5 percent.

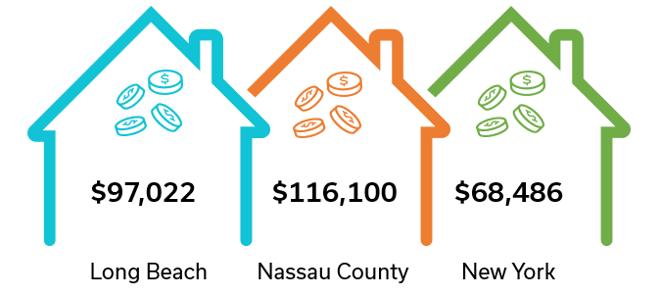

According to 2015-2019 ACS estimates and presented in Figure 3-7, Median Household Income Comparison, 2019, the median household income for Long Beach was $97,022, which was 16 percent lower than Nassau County ($116,100) and 42 percent higher than the State ($68,486). Though Long Beach has a higher education attainment rate than Nassau County, the median income is lower.

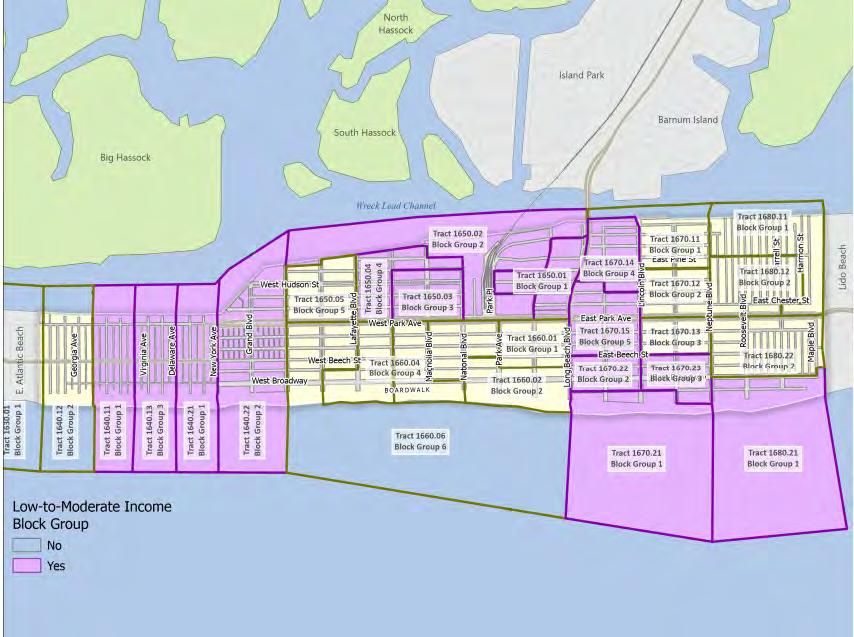

According to information from Nassau County and based on the 2010 U.S. Census, the City of Long Beach has fourteen designated low and moderate income (LMI) census block groups (see Figure 3-8, Low and Moderate Income), where at least 51 percent of persons are LMI individuals. Several of those census block groups are adjacent to Reynolds Channel. The majority of Long Beach falls into the 20–40 percent LMI range.

S Figure 3-8: Low and Moderate

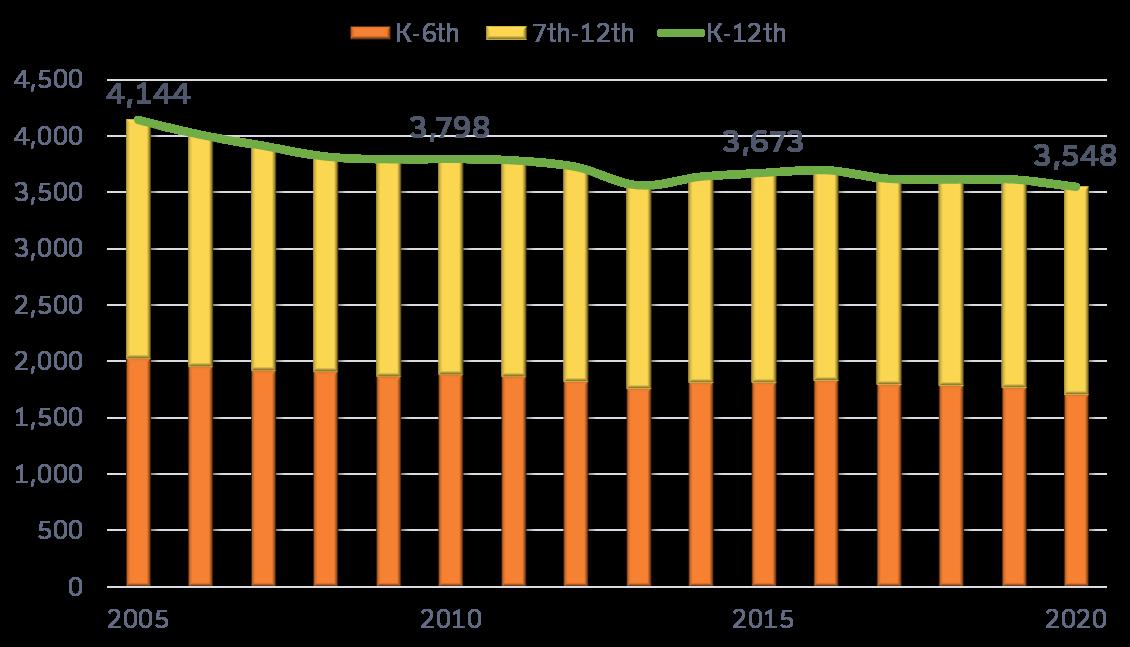

Between 2005 and 2020, public school enrollment in Long Beach declined by 15 percent (see Figure 3-9, Historical Long Beach School Enrollment). The City saw a steady decline in school enrollment from 2005 to 2013 (2012–2013 enrollment dipped due to Superstorm Sandy, when families had to temporarily relocate, other families moved away, and certain first floor apartments in the West End were no longer available), while enrollment declined at a slower rate from 2018 to 2020. Of note is that K-6 public school enrollment declined at a slower rate from 2005 to 2020 than enrollment for grades 7-12 during the same period.

When looking at the statistical data in the context of planning for its future, the City of Long Beach has been evolving in the following ways:

Total population is generally stable, however, the older adult (55-79) population is growing and working older adults (40-54) and early 20s populations are declining.

Household size is increasing.

Population density (persons/square mile) is higher than neighboring Nassau County communities.

There is higher educational attainment, but lower salaries than Nassau County.

Public school enrollment has declined but remains generally stable.

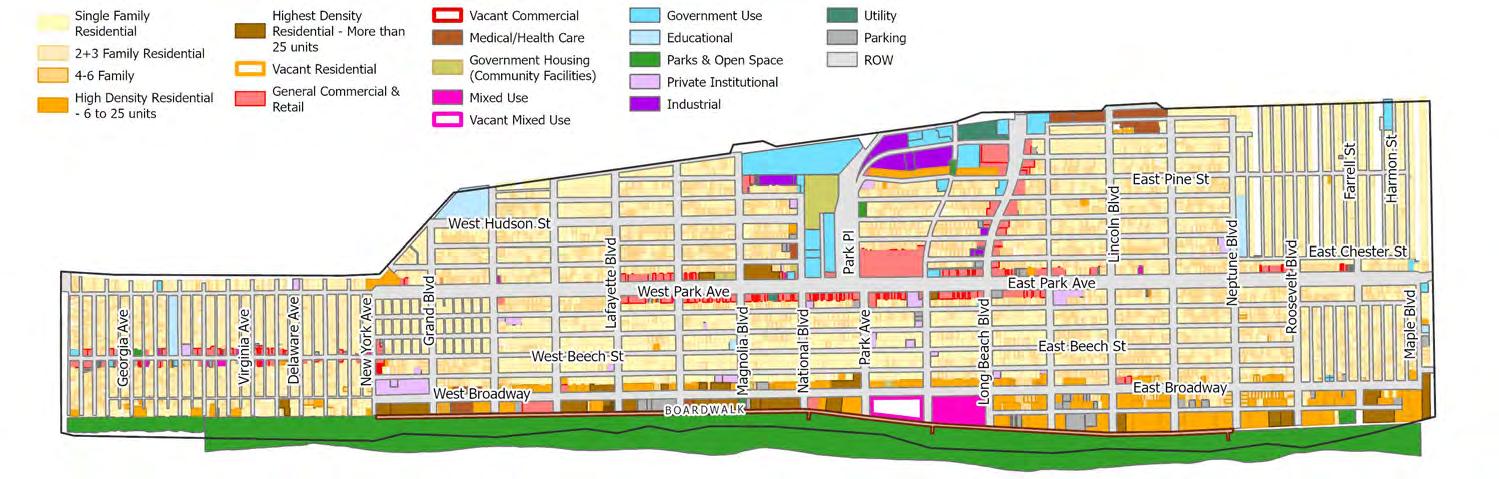

The City of Long Beach is largely a residential community. Other land uses include recreation and open space, public facilities, industrial, commercial, and community services (see Table 3-2, Existing Land Use, and Figure 3-10, Existing Land Use).

Residential land uses account for 48 percent of the City’s total land. The most prevalent residential land use is single-family homes (59 percent), followed by two- and three-unit attached residential homes (27 percent). The City has eight distinct neighborhoods, which offer a variety of housing types from singlefamily detached homes to townhomes to high-rise residential buildings with over 50 units.

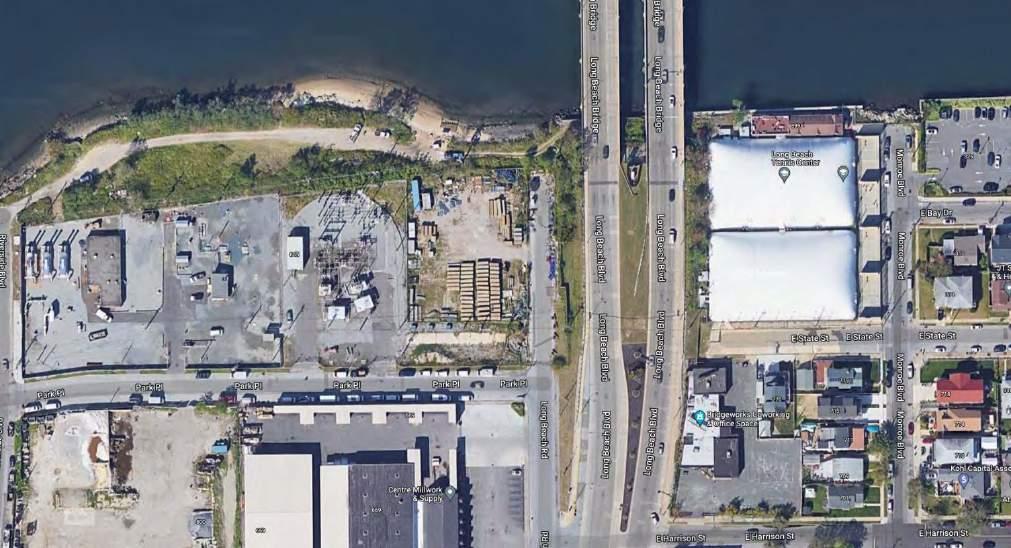

Commercial and industrial land uses account for only three percent of the City. The City’s central downtown is organized around the City Hall government center and the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) multimodal transportation center, which act as the hub of the main commercial district on Park Avenue. Long Beach Boulevard between the bridge and Park Avenue includes mainly automobile-centric retail uses.

Neighborhood-serving retail is located on Beech Street in the West End neighborhood and on East Park Avenue in the Canals and East End neighborhoods. The City’s Bayfront is defined by industrial uses, as well as public facilities and institutions.

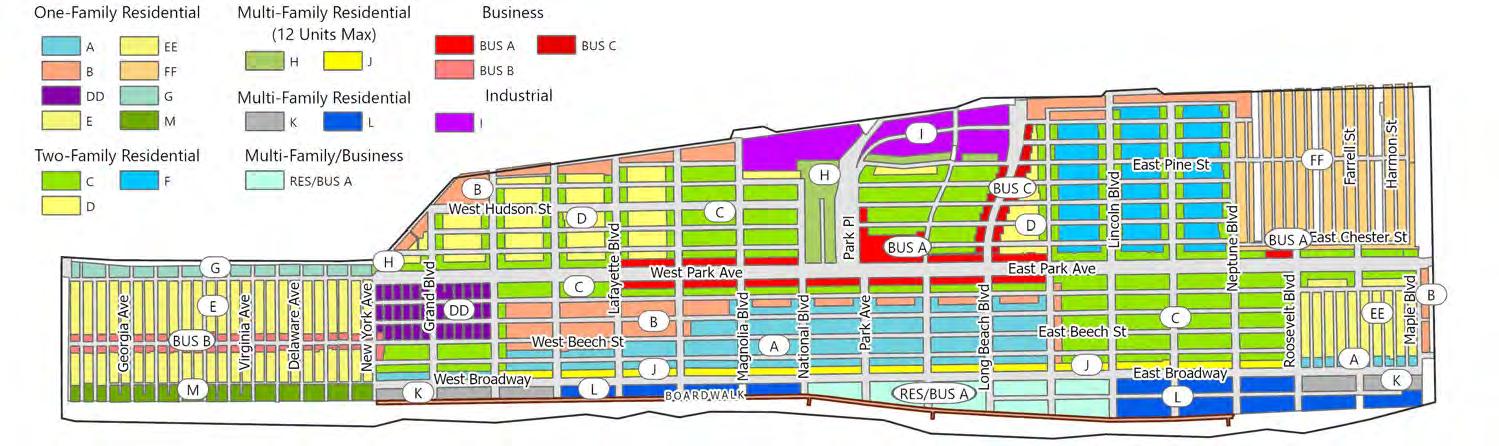

The City’s current zoning map (see Figure 3-11, Zoning Map) and ordinance date from the 1980s. The traditional grid pattern of the City features wide boulevards and narrow side streets. Most of the City is zoned for one, two, and other multi-family residential uses, with business and industrial districts comprising the remainder of the City’s development pattern. Since that time, the City has amended discreet sections of the Zoning Code to address pressing issues. Discussions with City staff, the Planning Advisory Board (PAB) and Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA) have indicated a more comprehensive review and update of the Zoning Code and map are required to accommodate changing conditions and preferences, including resiliency needs and recommendations provided herein.

2+3 Family Residential

4-6 Family

High Density Residential - 6 to 25 units

Highest Density Residential - More than 25 units

Vacant Residential

General Commercial & Retail

Vacant Commercial

Medical/Health Care

Government Housing (Community Facilities)

Mixed Use

Vacant Mixed Use

Government Use

Educational

Parks & Open Space

Private Institutional Industrial Utility Parking ROW

Road Islands

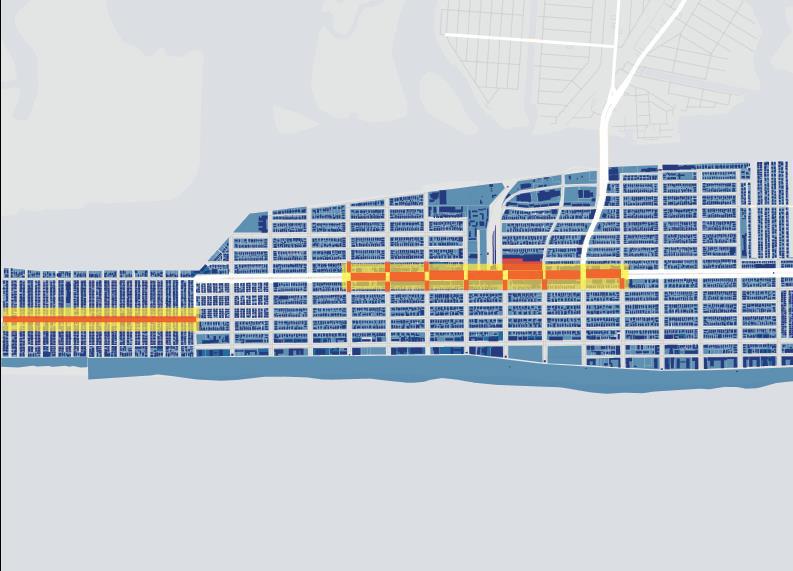

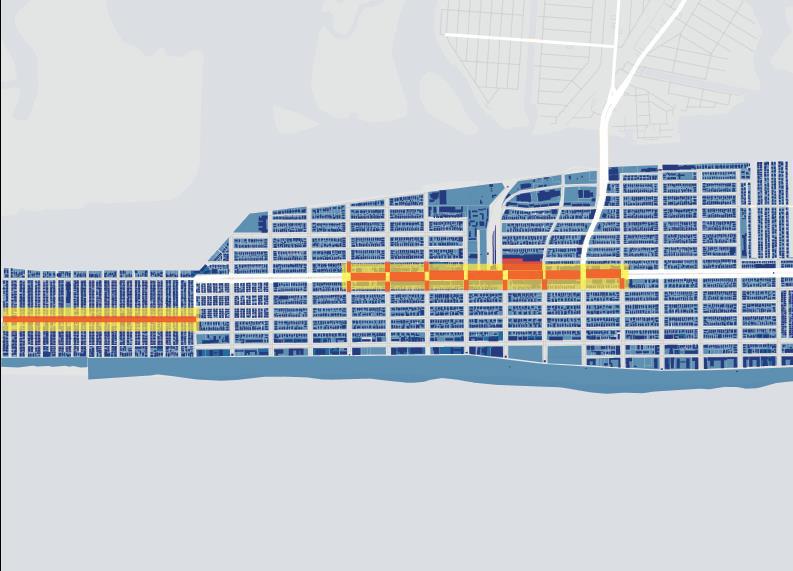

As shown in Figure 3-12, Opportunity Sites, the City has identified several opportunity sites for potential development, including the City Hall/Kennedy Plaza/ LIRR multimodal center/parking garage sites, the Stop & Shop site along East Park Avenue, which has been identified in the City’s planning and policy documents for more than 25 years, the Bayfront Sewage Treatment Plant to the west of the LIRR tracks, and several other sites along the Bayfront between the LIRR tracks and Long Beach Boulevard, several of which are City-owned. These areas are categorized by underutilization and are in the federal Opportunity Zone and New Markets Tax Credit areas. Some of these properties border the North Park community, which is an environmental justice area.2

The City of Long Beach is primarily residential.

The Zoning Code and Map are in need of updating.

Economic development/redevelopment and reuse sites have been identified as opportunity sites.

2 Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

Several opportunity zones have been identified for economic development and the surrounding communities should be involved as the City considers paths forward.

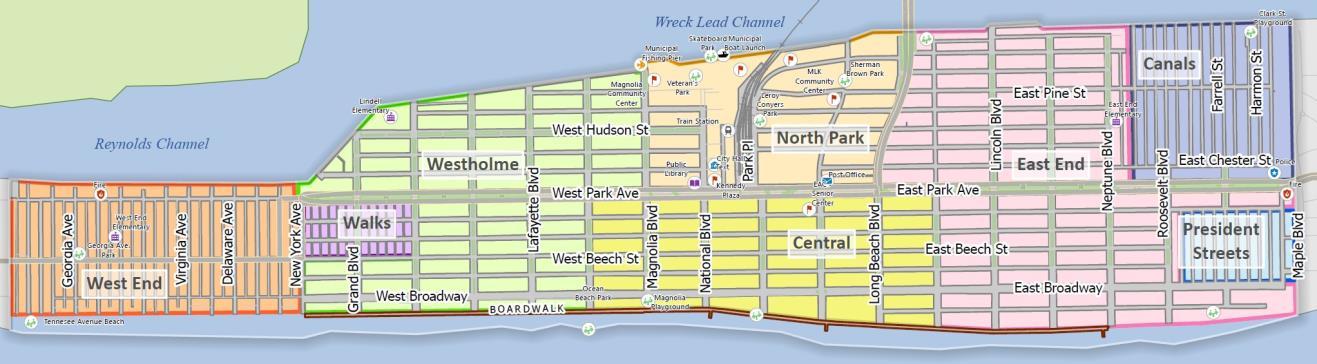

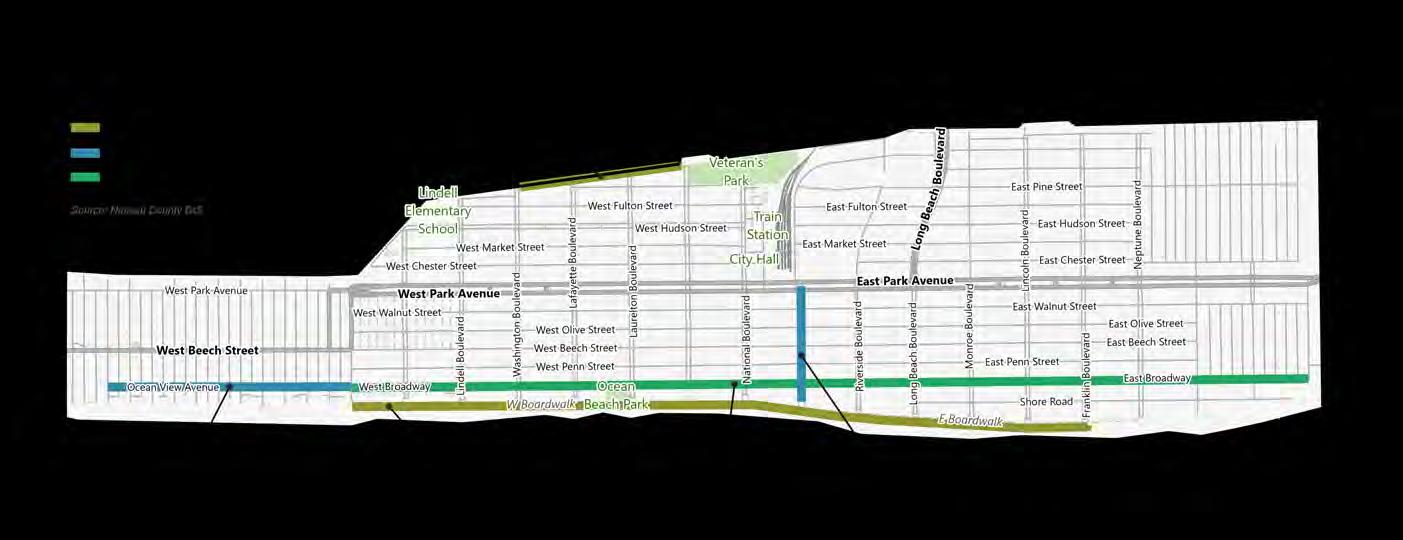

The City of Long Beach hosts eight neighborhoods, as shown in Figure 3-13, Long Beach Neighborhoods, each unique with its own identity and character. These neighborhoods are the West End, Westholme, the Walks, Central District, North Park, the East End, the Canals, and the President Streets. While each neighborhood offers both single and multi-family housing options, housing challenges exist.

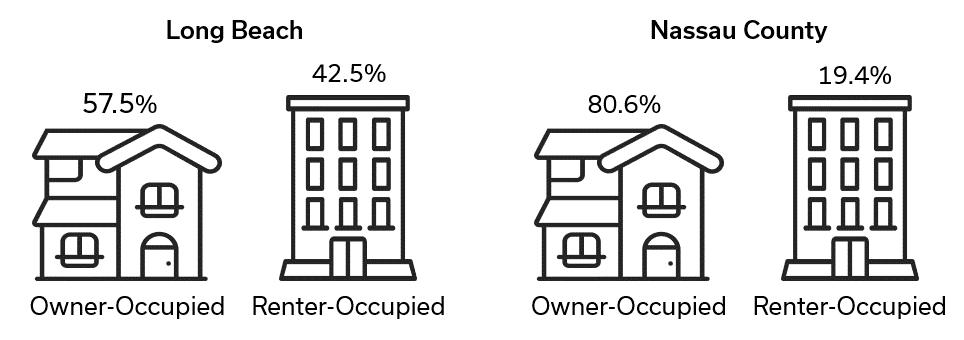

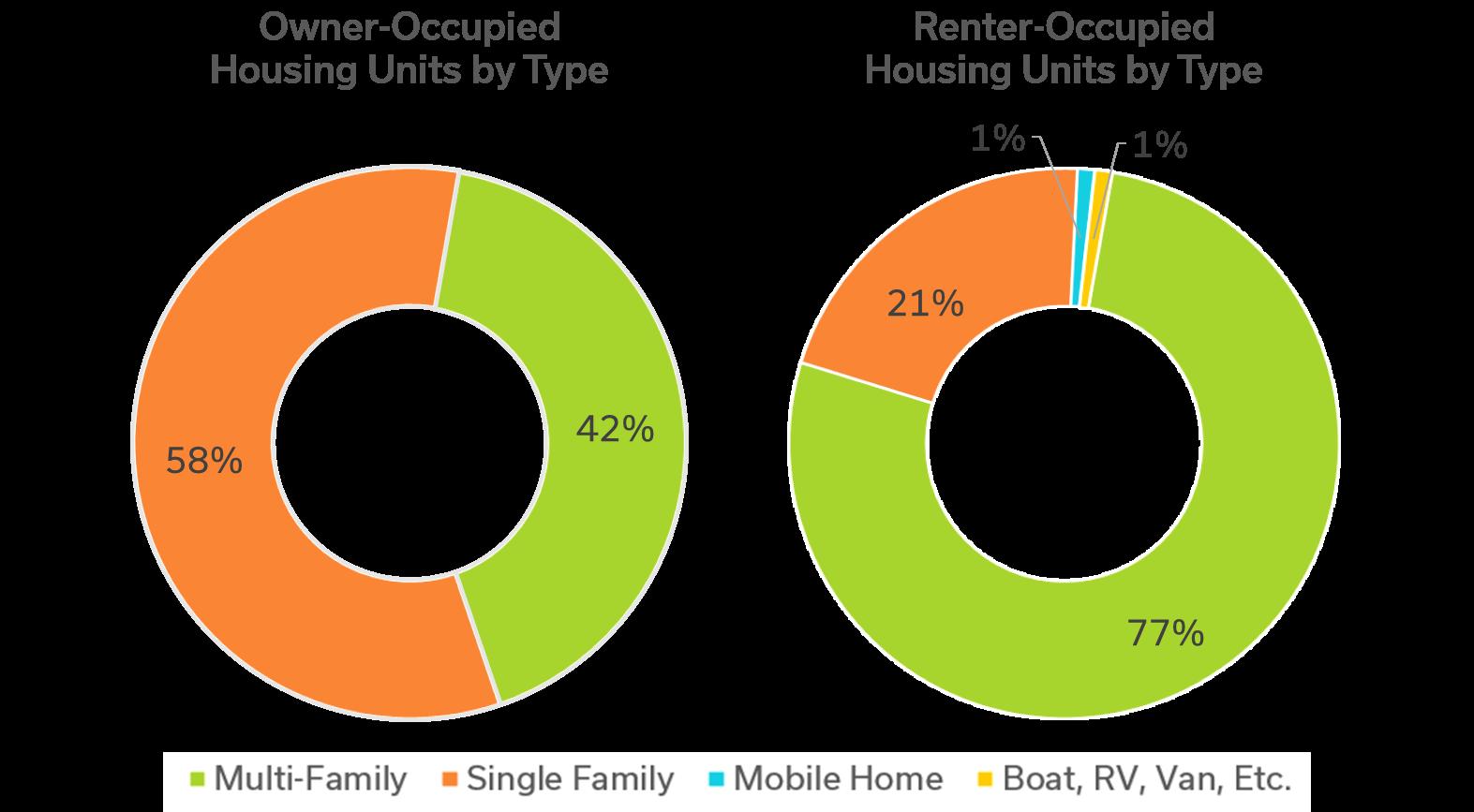

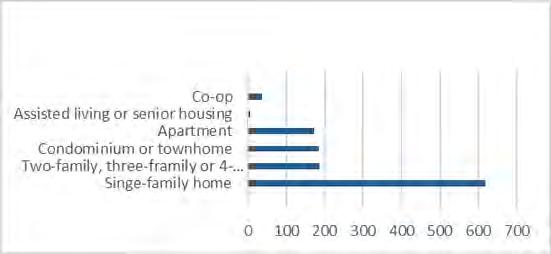

The City has a larger portion (42.5 percent) of renteroccupied housing than that of Nassau County (19.4 percent), even with high-rise units in Long Beach offering the opportunity for ownership (see Figure 3-14, Housing Tenure, and Figure 3-15, Housing Units by Type), which could be explained by the high number of “snow-bird” residents. While there are many hybrid arrangements for housing tenure that exist somewhere between renting and owning (community land trusts, co-ops, residential hotels, etc.), most owner-occupied housing in Long Beach is single-family homes (58 percent); by comparison,renteroccupied homes are largely multi-family (77 percent).

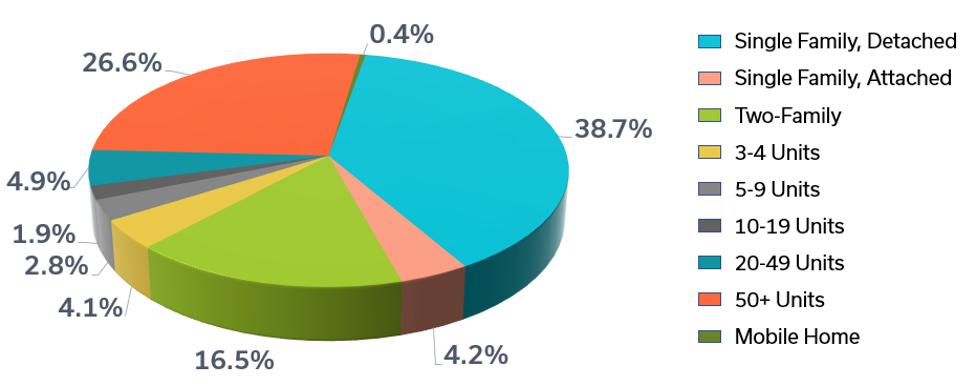

A diversity of housing types and affordability are central to the goals of the City of Long Beach and its residents. The City boasts a rich history of generational families that love to live in Long Beach and pass down their homes. While the homes of Long Beach residents come in all shapes and sizes, single-family detached residences (38.7 percent) and multi-family developments with 50+ units (26.6 percent) are the most common housing types (see Figure 3-16, Long Beach Number of Units in Structure).

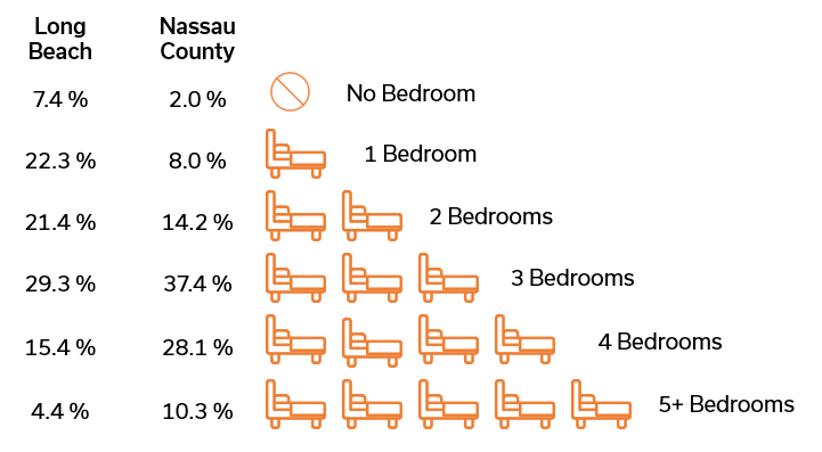

As shown in Figure 3-17, Housing Units by Number of Bedrooms, Long Beach’s unit sizes (number of bedrooms) are fairly evenly split, with 22.3 percent of the housing stock comprising one-bedroom units, 21.4 percent two- bedroom units and 29.1 percent three-bedroom units.

Nassau County is less diverse than the City, with approximately 75 percent of units comprising three or more bedrooms.

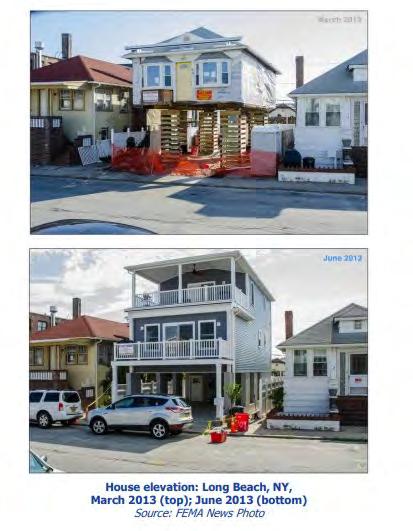

Home construction in Long Beach has kept pace with Nassau County, experiencing a two percent increase between 2010 and 2020, but has lagged behind New York State within that same time frame (see Table 3-3, Home Construction). Since 2012, and partly as a result of rebuilding after Superstorm Sandy and the reuse of vacant and underperforming parcels, the City has permitted five new multi-family dwellings and 493 one-and two-family dwellings.3 Balancing resiliency with preserving neighborhood character has been a challenge for the City of Long Beach post-Superstorm Sandy, as homes were rebuilt and elevated above Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Base Flood Elevation (BFE). To reduce risk of damage due to flooding, and comply with FEMA regulations, approximately 1,200 units (between 10 and 15 percent) of the City’s housing stock was required to be raised above BFE. This new building typology altered the traditional streetscape, with second-story additions and raised building elevations changing the neighborhood scale (see Figure 3-18, FEMA Base Flood Elevation).

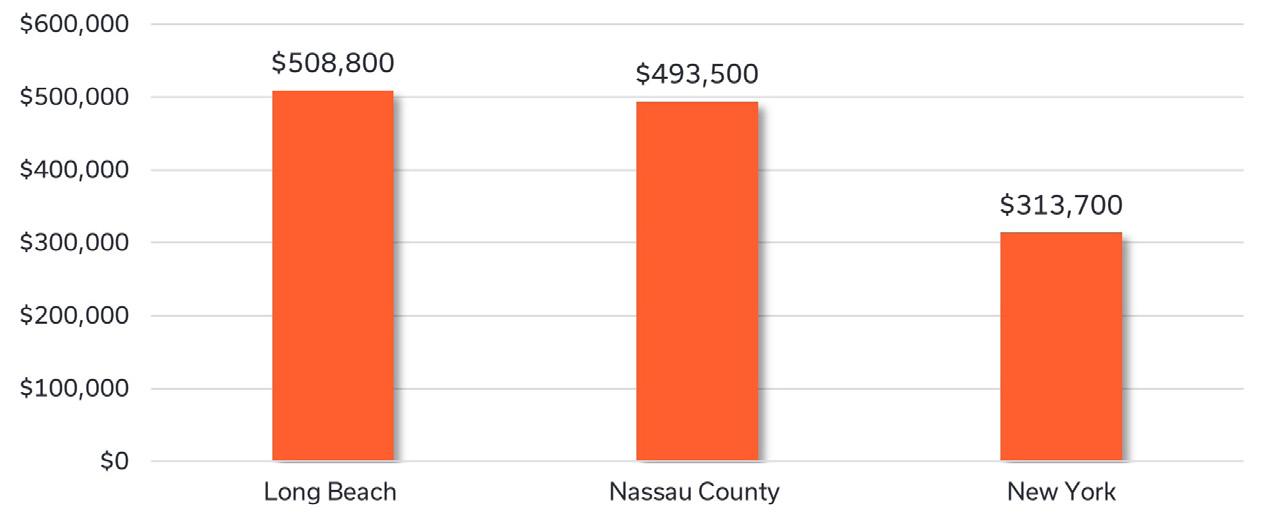

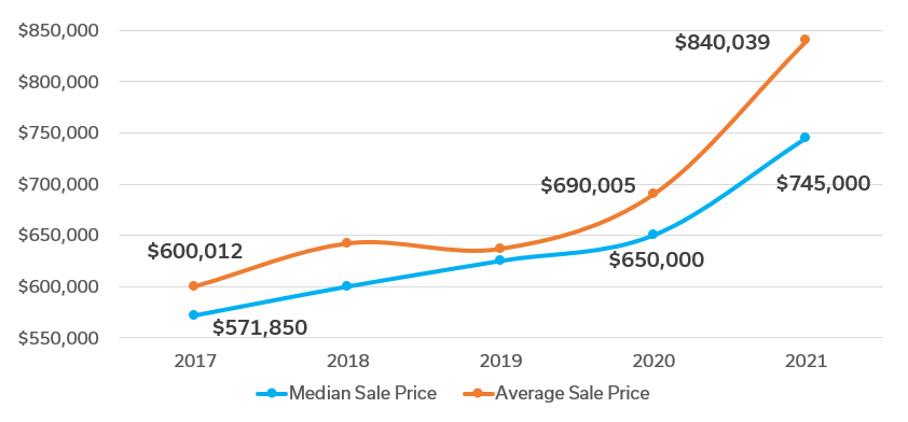

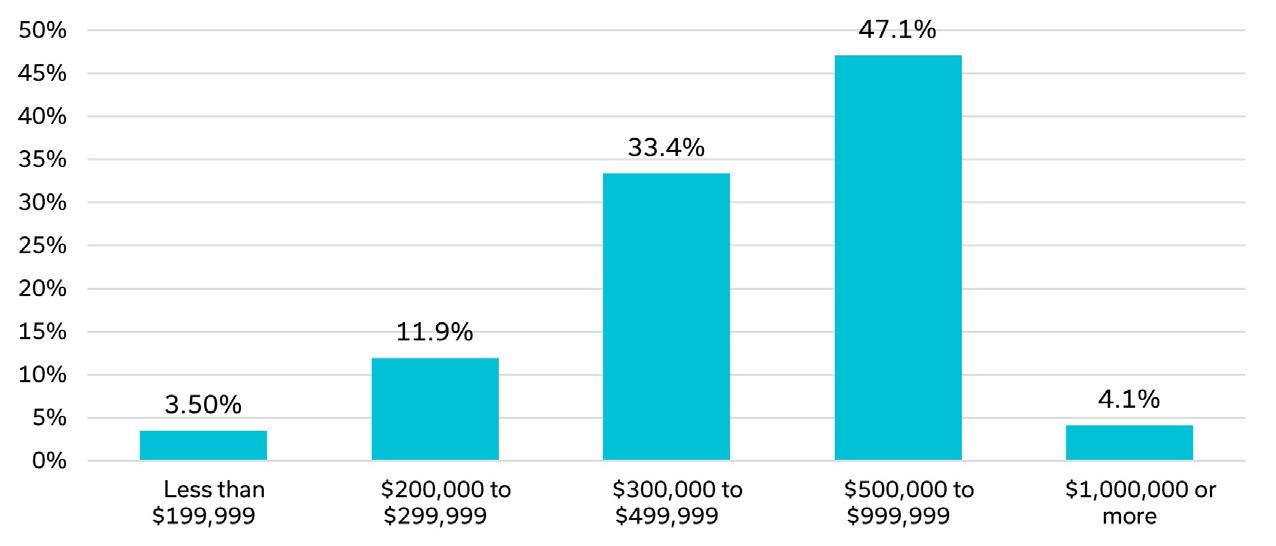

Despite the reality that incomes are lower in Long Beach than in Nassau County, median home values are higher exacerbating housing affordability issues. Nearly half of all homes in the City are now valued between $500,000 and $1,000,000, with only 3.5 percent of homes valued less than $200,000 (see Figure 3-19, Median Home Value, 2019, and Figure 3-20, Long Beach Distribution of Owner-Occupied Home Values). Home prices in Long Beach rose 22 percent between 2020 and 2021, as shown in Figure 3-21, Five-Year Long Beach Median and Average Home Sale Prices, largely due to increased demand resulting from New York City residents purchasing housing outside the City during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nassau County median home sale prices have also rapidly increased since 2019.

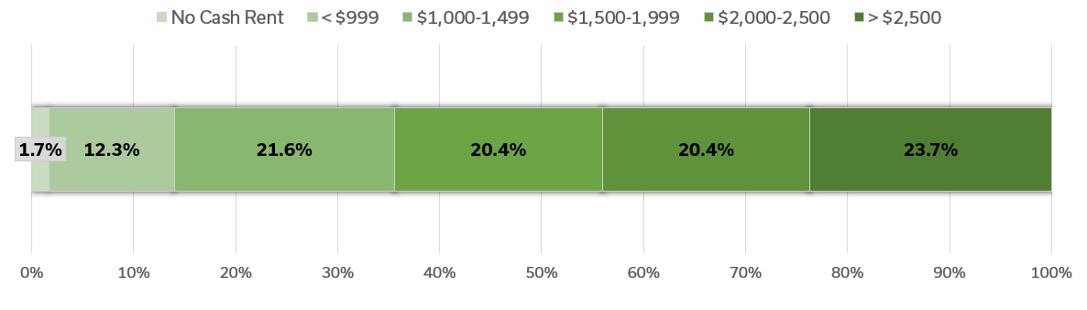

Housing rental costs in Long Beach are distributed evenly across several price points, though almost a quarter of units rent for more than $2,500 per month; approximately 12 percent of units rent for less than $1,000, but this does not guarantee affordability needs are being met (see Figure 3-22, Long Beach Distribution of Gross Monthly Rental Costs).

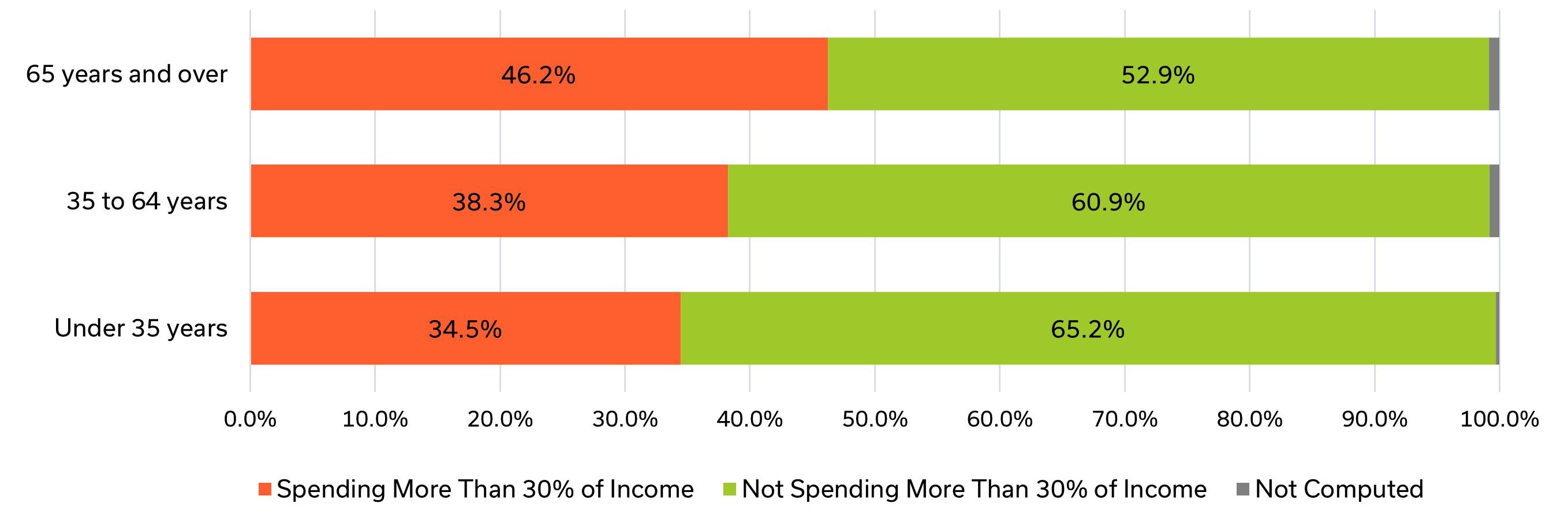

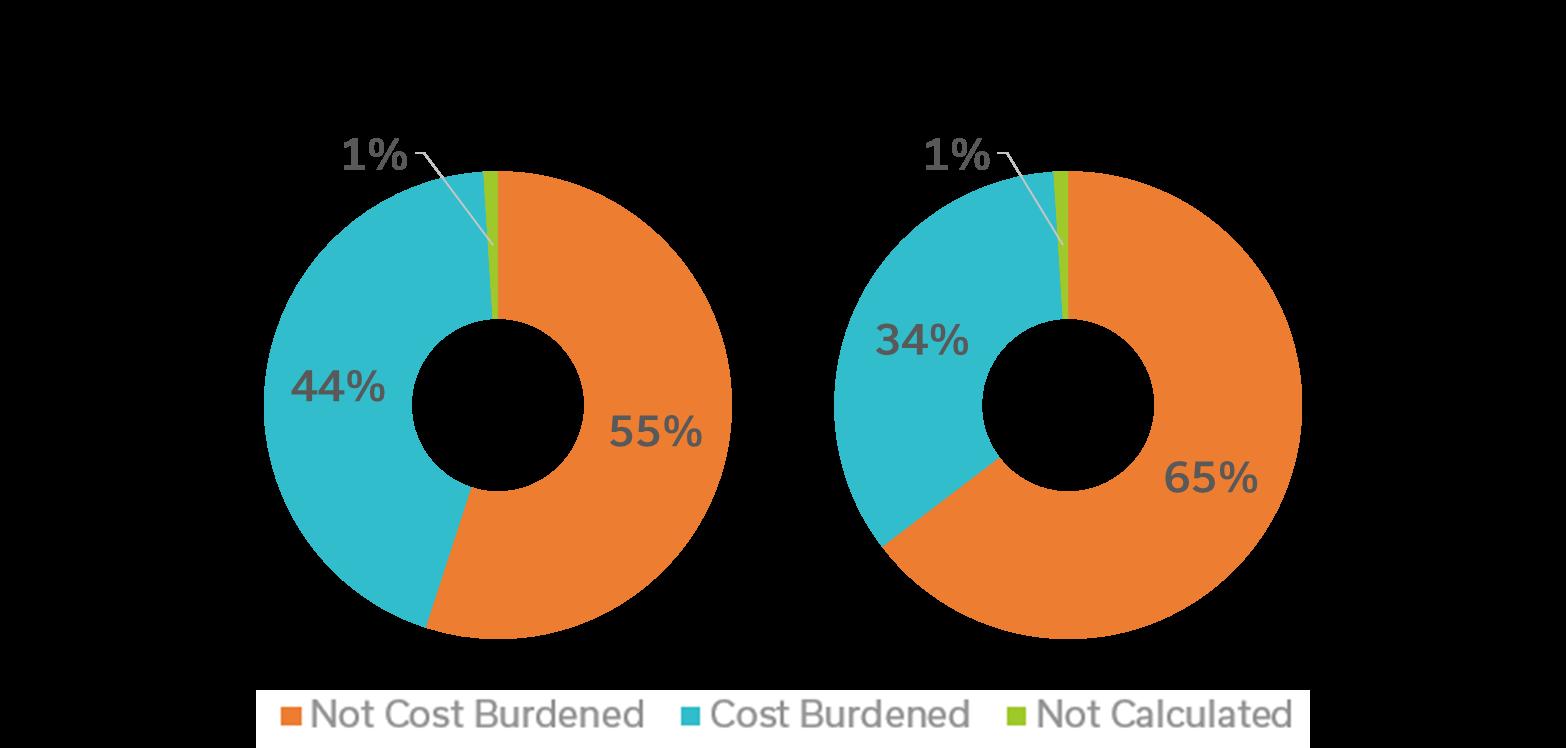

Generally, housing is considered “affordable” when monthly expenditure (excluding utilities) does not exceed 30 percent of gross monthly income. Using ACS 2015-2019 estimates, the median household income for City of Long Beach was $97,022. At this income level, housing would be considered affordable with costs lower than $2,425 per month. Thirty-six percent of Long Beach households qualify as low income (earning less than 80 percent of the Area Median Family Income [AMI]), compared to just under 25 percent of Nassau County households. In Long Beach, most households earning less than

80 percent of the AMI are cost burdened, and 74 percent earning less than 30 percent of the AMI are severely cost burdened (spend 50 percent or more of household income on housing). Nearly 35 percent of Long Beach owner-occupied households spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs. Sixty-seven percent of renter-occupied households earning less than 30 percent AMI are severely cost burdened, with 44.4 percent of Long Beach renteroccupied households spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs (considered cost burdened). Seniors (65 years and over) are more likely to be cost burdened, as seen in Long Beach with almost half (46.2 percent) of seniors spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs (see Table 3-4, Housing Affordability; Figure 3-23, Cost Burden for Renters and Owners; and Figure 3-24, Portion of Income Spent on Housing, by Age of Householder in Long Beach).

S Table 3-4: Housing Affordability

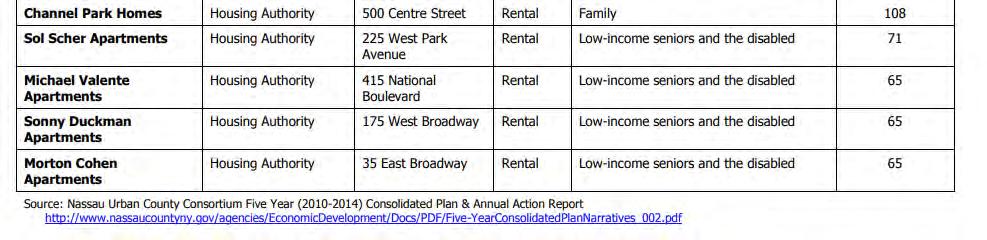

Long Beach offers more subsidized housing units than other Nassau County communities per capita. The Long Beach Housing Authority maintains five (5) developments:

f Channel Park Homes

f Sol Scher Apartments

f Michael Valente Apartments

f Sonny Duckman Apartments

f Morton Cohen Apartments

Three hundred eighty-nine Section 8 rental vouchers are available, with 299 vouchers presently issued. Pinetown Homes provides 121 units of lower-cost housing.

Despite many home-ownership opportunities in densely populated Long Beach, the rate of ownership is lower in Long Beach than in Nassau County because there are more rental options than in the rest of the county.

Even though incomes are lower in Long Beach than in Nassau County, median home values are higher, exacerbating housing affordability issues.

Long Beach offers a diverse housing stock, with an even distribution of one-, two-, and three-bedroom units.

Rental and sales prices are rising at an increasing rate.

Thirty-six percent of the City’s population qualify as low income.

Thirty-four percent of the City’s homeowners and 44 percent of the City’s renters are cost burdened, which is on par with Nassau County.

To partially offset this housing cost burden, Long Beach offers more subsidized housing than other Nassau County communities.

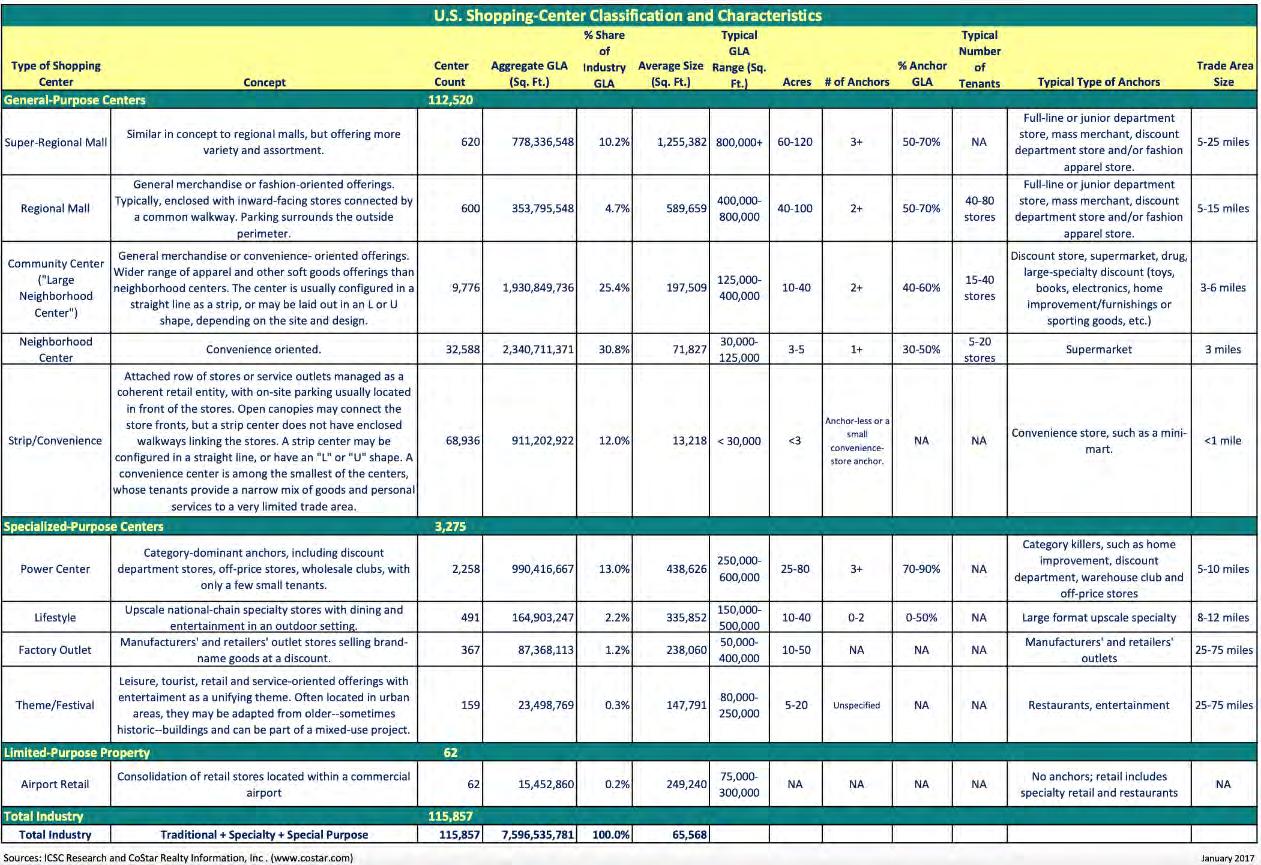

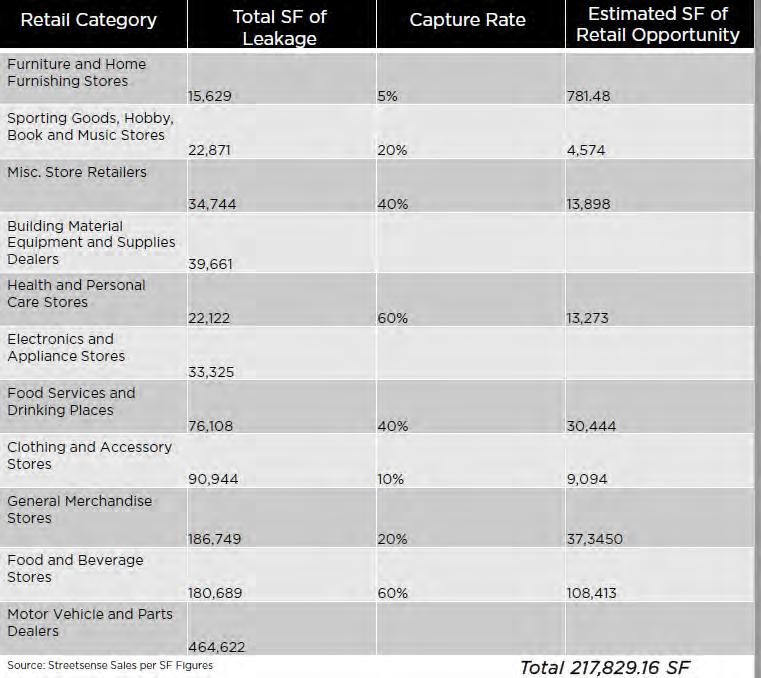

The City of Long Beach offers more than 200,000 square feet of retail development in five neighborhoods: Beech Street in the West End neighborhood, the Central Business District along Park Avenue, between Neptune and Pacific Streets on East Park Avenue, Long Beach Boulevard at the City entryway, and the Boardwalk. Collectively, retail offerings include neighborhood goods and services, food and beverage, general merchandise and apparel, furnishings, and other miscellaneous retailers. See Appendix E for more information on the commercial corridors and districts.

The 1,042 businesses in Long Beach are primarily focused on service (45 percent), retail (28 percent), and finance, insurance, and real estate (13 percent, collectively). The largest employment sectors are in educational services (16 percent), health and social services (13 percent), scientific and technology services (10 percent), and retail (nine percent). The Long Beach City government and school district employ 21 percent of the local workforce.

According to ACS data, between 2010 and 2019, Long Beach gained an estimated 305 jobs (see Table 3-5, Annual Employment Estimates). The largest employment gains were in construction, while the largest losses were in public administration and wholesale trade. In losing 57 jobs, the agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, and mining industry saw the steepest percentage drop. The education section maintains the largest workforce.

S Table 3-5: Annual Employment Estimates

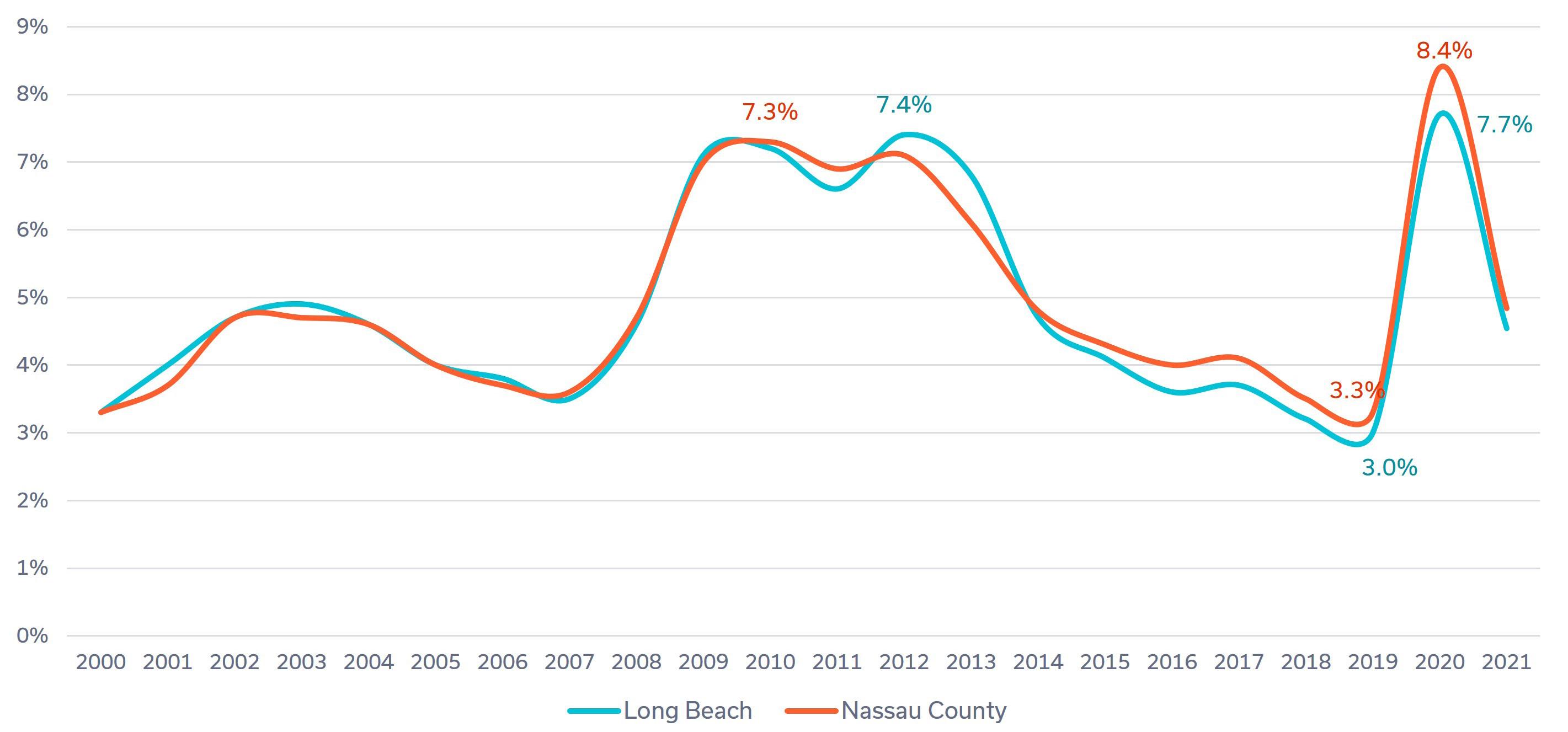

According to the New York State Department of Labor, Long Beach’s unemployment rates have paralleled Nassau County’s over the last 20 years. The unemployment rate in Long Beach declined

significantly between the 2012 peak and 2019 but increased dramatically due to the COVID pandemic, when unemployment rose to nearly eight percent.

In 2021, the unemployment rate decreased to 4.5 percent (see Figure 3-25, Long Beach and Nassau County Annual Unemployment Rate).

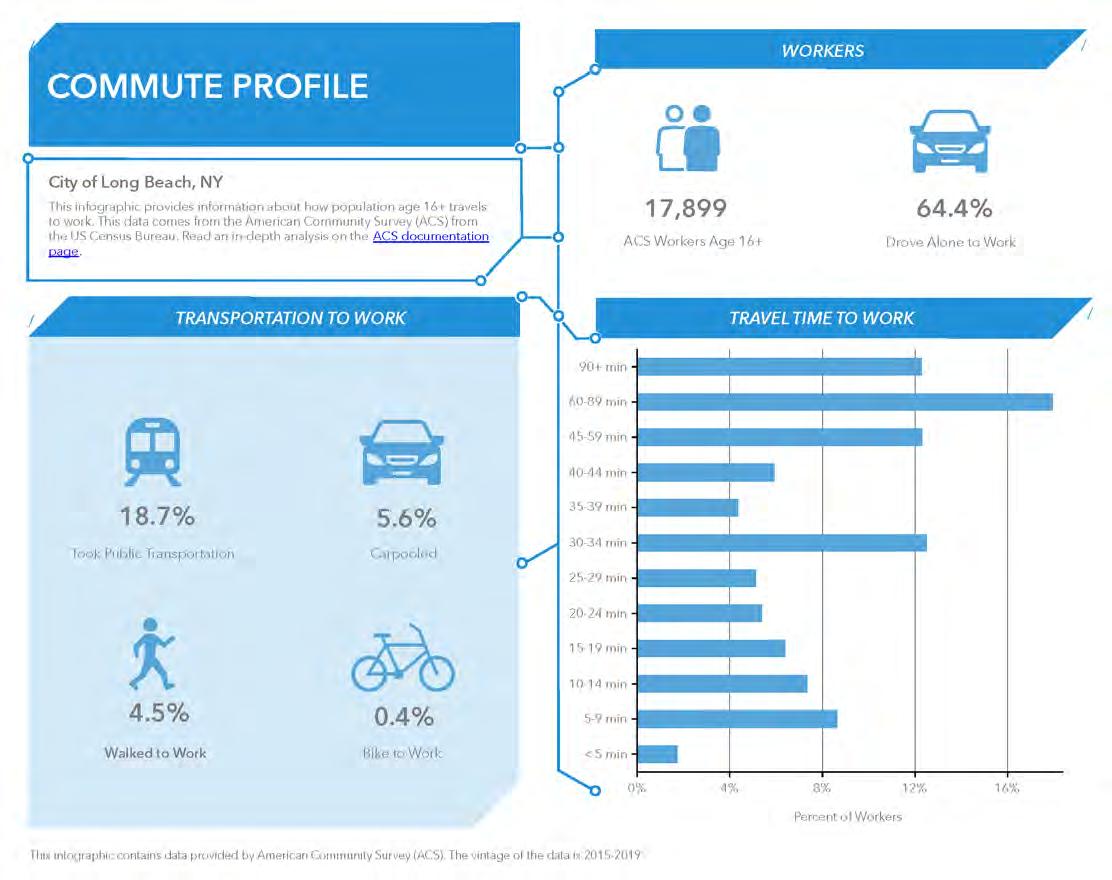

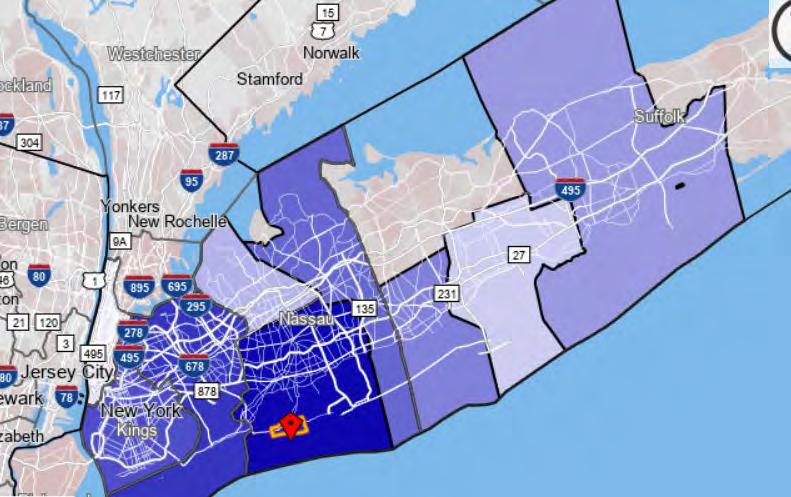

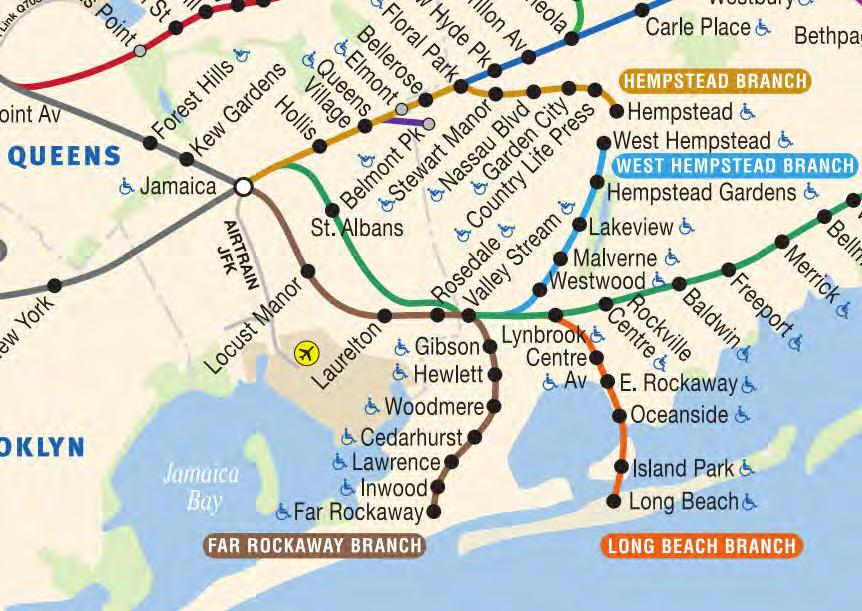

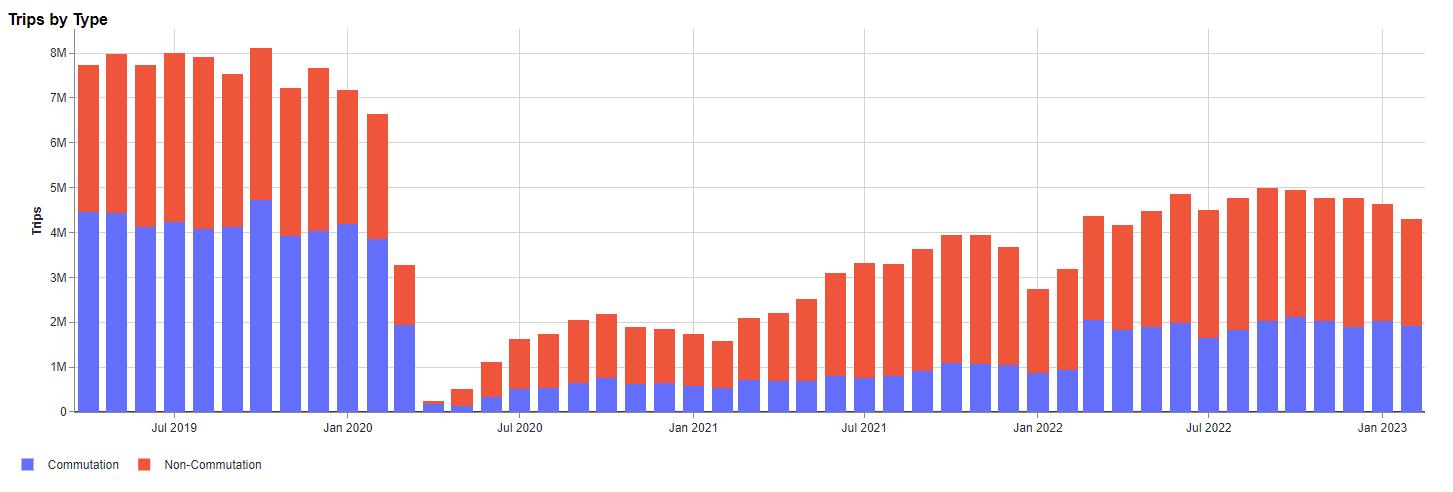

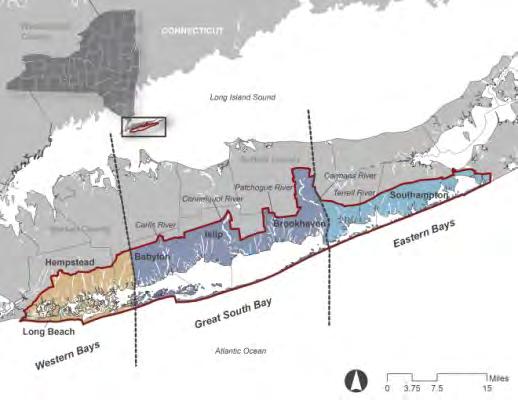

Vehicular and public transportation access to the City of Long Beach occurs via three bridges, the LIRR, which connects Long Beach to the New York metropolitan area, and the Amtrak New England rail system. The road system (see Figure 3-26, Road Classification) consists of two county arterials, Long Beach Boulevard, and the section of Park Avenue from Long Beach Boulevard east; one principal arterial (City owned), Park Avenue; and several collectors roads, that feed into the arterials.4 Though LIRR ridership declined due to the COVID-19 pandemic, numbers are slowly returning to pre-pandemic numbers. The Long Beach LIRR station is the sixth busiest in Nassau and Suffolk Counties and is scheduled by the MTA for an overhaul in 2023/24. LIRR ridership is projected to recover 80 percent of its pre-pandemic ridership by 2026.

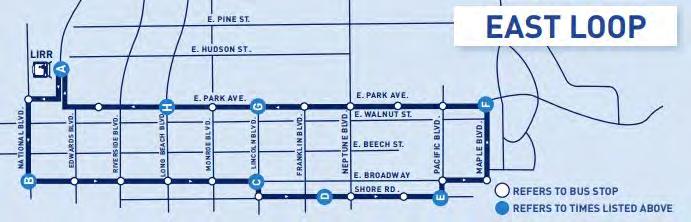

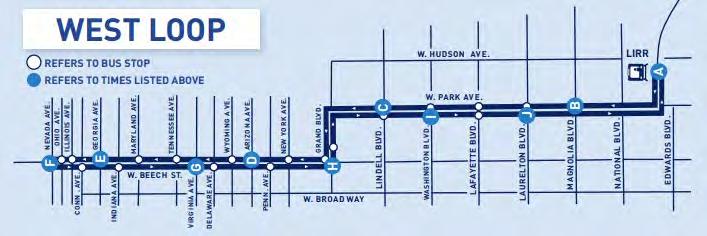

The local Long Beach bus system runs along an East Loop and a West loop providing services within the City to the LIRR station, offers a shopping bus schedule and Able Ride (see Figure 3-27, Public Transportation). The Nassau County NICE bus system terminates at the multimodal center. Bus

4 NYSDOT: Roads classified as collectors and arterials may be eligible for state and federal funding programs.

ridership also decreased during the pandemic, shifting from 15,000-20,000 total riders per month pre-pandemic to, most recently, around 7,500 riders per month.5

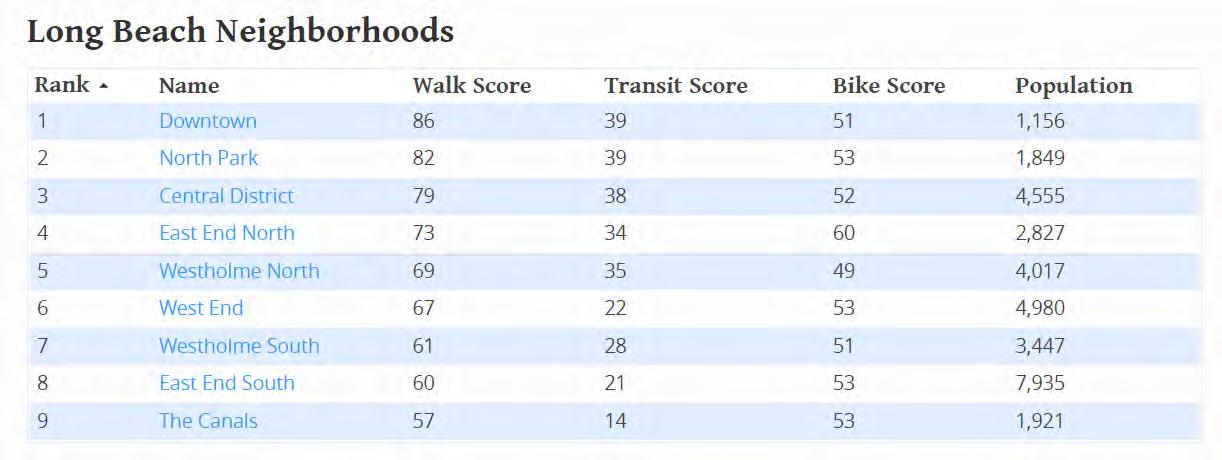

Citywide, Long Beach achieves a high WalkScore6 for transit, bicycle infrastructure, and walkability (see Table 3-6a, WalkScore Ratings).7

5 City of Long Beach.

6 WalkScore—an organization that measures the walkability, transportation, and bikeability of communities in the U.S., Canada, and Australia—shares data collected from their three rating systems: Walk Score, Transit Score, and Bike Score. The score indicates how well a location is served by pedestrian and biking infrastructure and public transportation. A higher score indicates better infrastructure, connectivity, and network. The Walk Score is based on the distance to amenities nearby, population density, road metrics, and other data.

7 https://www.walkscore.com/NY/Long_Beach

Functional Road ClassNY DOT

Principal Arterial Other

Minor Arterial

Major Collector

Road Islands

Railways

Long Island Rail Road

S Figure 3-26: Road Classification

S Figure 3-27: Public Transportation

It is interesting to note that data analyses prepared by WalkScore indicated Long Beach’s commuting scores are lower than national averages, but ACS commuter data8 shows higher than national average percentages of Long Beach commuters take public transit or opt for non-motorized options, including walking and bicycling (see Table 3-6b, American Community Survey Commuter Data).

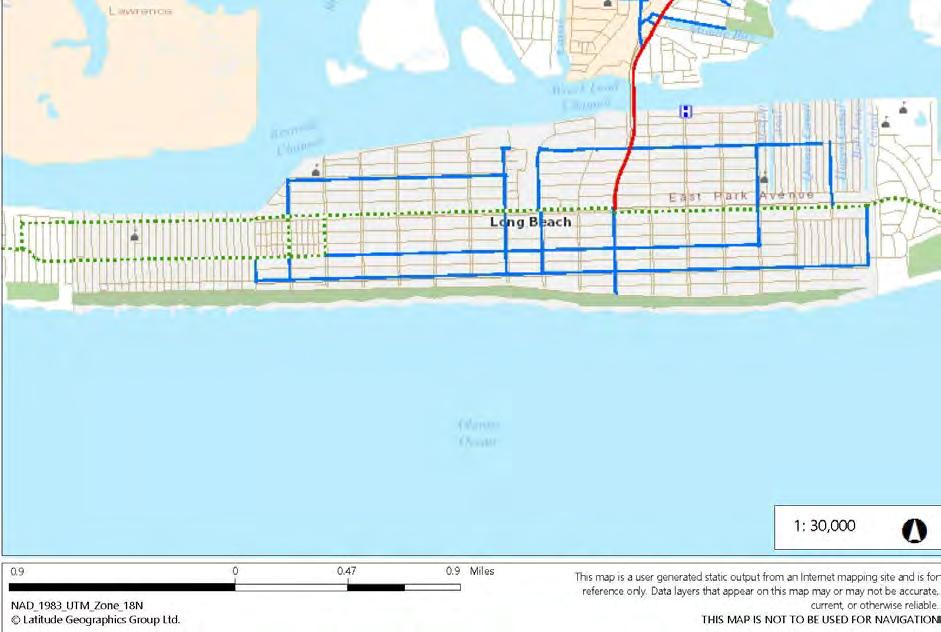

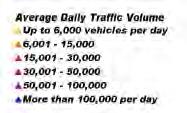

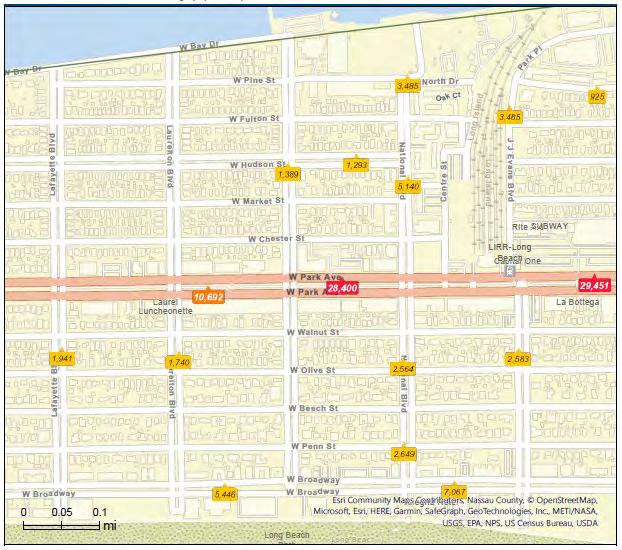

The highest traffic volumes within the City occur along East Park Avenue, the City’s major commercial corridor and principal arterial, and Long Beach Boulevard. Long Beach Boulevard and Park Avenue going east from Long Beach Road are County roads. The Long Beach Boulevard Bridge holds the highest traffic volumes (see Figure 3-28, Citywide Traffic Volumes). Traffic volumes decrease around Park Avenue in the vicinity of the LIRR Station and along West Park Avenue, thinning out west of the LIRR

Station and into the neighborhoods (except along Broadway). Commercial traffic, including heavy trucks, travel along New York State Truck Routes, the Long Island Expressway (LIE) and the Sunrise Highway to and from Long Beach.

Many areas in the City have inadequate on- and offstreet parking, where demand significantly exceeds supply. The parking shortage results in increased traffic congestion and negatively impacts air quality and quality of life for residents, as motorists circle through local streets seeking available parking and/or waiting for spaces to open. Demand for parking proximate to the Ocean waterfront has also increased as more

residents and visitors seek recreational opportunities. While the West End and Park Avenue commercial districts have a total of approximately 1,600 available on-street and public parking spaces, there are limits and rules around parking times and designated spaces that make it difficult for customers, workers, residents, and visitors to park for an extended period, drawing them away from spending time in these main commercial districts. While employees and visitors may park in the LIRR garage on the weekends when the garage is not used for commuters, the distance and challenges crossing Park Avenue make these parking options less appealing. The City is studying

how to make parking accessible and have sufficient space turnover to meet demand.

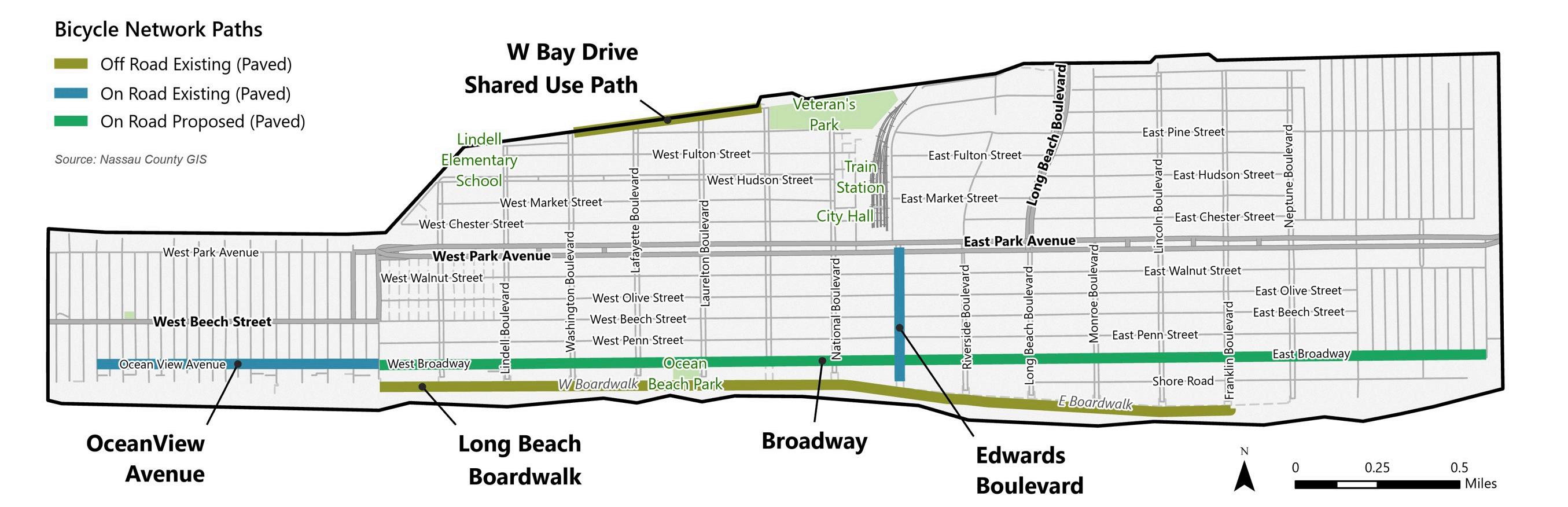

Long Beach’s strong existing on and off-road shareduse paths and bicycle network accommodates a wide variety of non-motorized uses (see Figure 3-29, Bicycle Network). The City’s trail network consists of the 2.25-mile Boardwalk along the Atlantic Ocean, bicycle lanes on Edwards Boulevard (recommended in the City’s Complete Streets Program and grant funded), and shared use paths on West Bay Drive, along the Bayfront, Ocean View, and Broadway. However, although prioritized in many of the City’s

planning documents, the City lacks a fully connected network, particularly from north to south. Per a 2021 Bike Score assessment, Long Beach’s Bike Score (53) citywide was less than the national average (67) likely due to the lack of bicycle infrastructure connecting Long Beach’s neighborhoods to local and regional employment centers.9 At the neighborhood level, a review of the WalkScore assessment, reveal downtown Long Beach, particularly along the central commercial corridor, achieves the highest transit, bikeability, and walkability scores, followed closely by the North Park neighborhood. Bicycle usage within the City, particularly for recreational cycling along the City’s beachfront, is high per City indicators, thus encouraging an expansion of the shared-use path network both within the City and to neighboring communities. Plans are in process to connect with the communities to the west.

The Long Beach City Council committed the City to Complete Streets in 2013 when it adopted legislation to use Complete Streets principles as much as possible. Complete Streets are safe for all users,

9 Bike Score—a method of measuring a community’s bike ability based on bike lanes, landscape, road connectivity, amenities, and percent of people who bike to work—is scored out of 100; thus, the higher the score, the more bike-friendly a community is considered.

especially seniors, comfortable, and convenient for travel for everyone, regardless of age or ability— motorists, pedestrians bicyclists, and public transportation riders. Over the last decade, Long Beach has received grant funding for the Complete Streets program, and other built infrastructure projects, which improved bicycle lanes, crosswalks, and curb extensions, including the Edwards Boulevard