4 minute read

The Bauhaus, László Moholy-Nagy, and Milwaukee

Lisa Sutcliffe, Herzfeld Curator of Photography and Media Arts, Monica Obniski, Demmer Curator of 20th- and 21st-Century Design, and Ariel Pate, Assistant Curator of Photography

To mark the centennial year of the founding of the Bauhaus (1919–1933), the innovative art, architecture, and design school in Germany, the Museum put together a special presentation in its Bradley Galleries of Modern Art. Highlighted is the artist, designer, and theorist László Moholy-Nagy (American, b. Hungary, 1895–1946), one of the school’s key figures. Even if some of you visited the display, new works were rotated in when the Museum was still open, and we thought what better time to take, at your leisure, a deeper dive. Among the objects that you can explore here, and in the 360 tour of the display, are classic Bauhaus design books and a new addition to the Museum’s collection, a desk set Moholy-Nagy designed while working for the Wisconsin company Parker Pen.

The Bauhaus

German architect Walter Gropius (1883–1969) established the Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany, as a refuge for avant-garde artists and sought to create a singular artistic style across the fine and applied arts. The school, which later moved to Dessau and then Berlin, initially took the form of a utopian craft guild and offered workshops in furniture making, weaving, and metals, among others. The armchair pictured here, for example, which is in the Museum’s design galleries, is a rare survivor from when Marcel Breuer (American, b. Hungary, 1902–1981) was a student at the Bauhaus. The fabric is original and was woven by a currently unknown female designer within the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop.

Marcel Breuer, Lattenstuhl (model TI 1A), 1923. Purchase, Lucia K. Stern Trust, M2016.75. Photo by Martin Müller Fotografie, Berlin.

The Bauhaus was driven by functional analysis: how does one create a chair that is both simple in design and comfortable to sit in? Breuer accomplished this with strong, yet minimal supports and flexible straps that provide comfort by conforming to the small of the back and the shoulder blades.

László Moholy-Nagy

László Moholy-Nagy, [Self-portrait], 1925/26. Lent by the Archives Department, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Libraries.

László Moholy-Nagy taught at the Bauhaus from 1923 until 1928. He shared his inventive spirit with students through his novel classes in photography and composition and in the metals workshop that he oversaw. A polymath who experimented across media, the artist wanted to integrate the arts with current industry and technology to show how art could shape modern life.

Moholy-Nagy advocated an experimental approach to photography, including tight close-ups, negative images, and photograms, which he asserted could produce new ways to look at and understand the world. This approach came to be called New Vision, a term that defines a movement of artists who sought to expand human perception through photographic technology.

To make the photogram pictured below, Moholy-Nagy placed objects from his workshop on sensitized paper that he then exposed to light; the resulting image teeters between representation and abstraction. Following World War I, many artists jettisoned representational imagery.

László Moholy-Nagy, Photogram, 1925. Purchase, Richard and Ethel Herzfeld Foundation Acquisition Fund, M2006.31. Copy photo by John R. Glembin. © Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Between 1924 and 1929, Moholy-Nagy and Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius edited a series of fourteen books titled The Bauhausbücher, which surveyed the art being made at the time both within and beyond the Bauhaus. They aimed to inform the school’s faculty, while also reaching a broader public. Subjects ranged from theoretical approaches and products of the school to wider topics relevant to the avant-garde, such as Cubism and Dutch architecture. In terms of their graphic design, these books employed sans serif typefaces and gridded arrangements and made dynamic use of blank space.

Bauhausbücher 7 illustrates products of the school’s various departments, including the carpentry, glass, weaving, and metals workshops (the latter was directed by MoholyNagy). These items were generally designed with efficient mass-production in mind, and the Bauhausbücher series reflects a similar aim, as the books were made using modern commercial printing methods (in contrast with hand-printed or limited production books).

Designed and edited by László Moholy-Nagy, Edited by Walter Gropius, Published by Albert Langen Verlag, Neue Arbeiten der Bauhauswerkstätten (New Works from the Bauhaus Workshops), 1st edition, Bauhausbücher (Bauhaus Books) 7, 1925. Milwaukee Art Museum Research Center, purchase with funds from the Demmer Charitable Trust

László Moholy-Nagy, Nuclear II, 1946. Gift of Kenneth Parker, M1970.110. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In 1937, Moholy-Nagy moved to Chicago to lead the New Bauhaus, which became the Institute of Design in 1944 and was later incorporated into the Illinois Institute of Technology. Also in 1944, the president of the Wisconsin-based Parker Pen Company, Kenneth Parker, approached MoholyNagy to develop products and advise on a range of design issues. Among the many designs that Moholy-Nagy pursued for Parker is the ball-andsocket apparatus he invented and patented for their Magic Wand desk sets. The desk set here, a recent addition to the Museum’s collection, was found in Moholy-Nagy’s Parker Pen office after his death and employs the same apparatus. This set is unique, however, because its design and materials make it difficult to mass-produce, suggesting that he likely made it for his own personal use.

Pictured above is Moholy Nagy’s Nuclear II, which Kenneth Parker donated to the Museum in 1970. The artist made the painting a year after the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Nuclear II depicts a globelike sphere floating against a subtly textured background. Raggededged forms suggest continents or billowing mushroom clouds, while faint concentric circles in the light-colored box just left of center might be read as a target.

László Moholy-Nagy, Parker Pen Company, Pen Rest and Letter Holder, 1946 (with Parker 51 Pen, 1938, designed by Marlin Baker and Kenneth Parker). Purchase, with funds from the Lucia K. Stern Trust and the Demmer Charitable Trust, M2018.19a,b. Photo by John R. Glembin. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Milwaukee

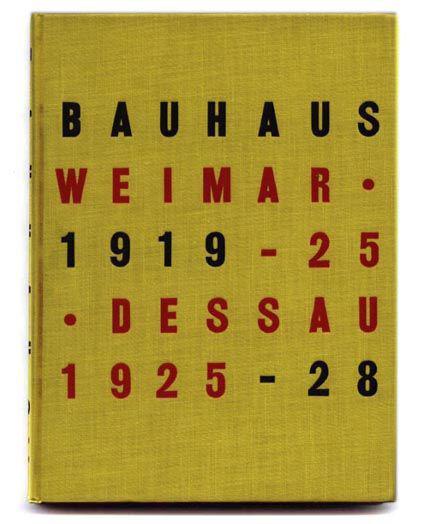

László Moholy-Nagy was known in Milwaukee even before his move to Chicago. In 1931, the Milwaukee Art Institute (1916–1957), a Milwaukee Art Museum predecessor, hosted the first traveling exhibition of his photographs in the United States. And in 1939, during the popular Milwaukee presentation of the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition Bauhaus 1919–1928, Moholy-Nagy came to give a lecture.

Designed and edited by Herbert Bayer, Edited by Walter Gropius, Edited by Ise Gropius, Bauhaus 1919–1928, 1938. Milwaukee Art Museum Research Center, purchase with funds from the Demmer Charitable Trust

This catalogue is from the exhibition that MoMA organized.

Take an even deeper dive into the gallery, with expanded content, including the voices of the curators, in the 360-degree experience.