8 minute read

BRAHMS REQUIEM

Friday, April 11, 2025 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, April 12, 2025 at 7:30 pm

Sunday, April 13, 2025 at 2:30 pm

ALLEN-BRADLEY HALL

Ken-David Masur, conductor

Sonya Headlam, soprano

Dashon Burton, bass-baritone

Milwaukee Symphony Chorus

Cheryl Frazes Hill, director

PROGRAM

JOHANNES BRAHMS

Ein deutsches Requiem [A German Requiem], Opus 45

Ein deutsches Requiem [A German Requiem], Opus 45

I. Selig sind, die da Leid tragen [Blessed are they that mourn]

II. Denn alles Fleisch, es ist wie Gras [For all flesh is as grass]

III. Herr, lehre doch mich [Lord, teach me]

IV. Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen [How amiable are Thy tabernacles]

V. Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit [Ye now therefore have sorrow]

VI. Denn wir haben hie [For here have we no enduring city]

VII. Selig sind die Toten [Blessed are the dead]

Sonya Headlam, soprano

Dashon Burton, bass-baritone

Milwaukee Symphony Chorus

The 2024.25 Classics Series is presented by the UNITED PERFORMING ARTS FUND and ROCKWELL AUTOMATION

The length of this concert is approximately 1 hour and 30 minutes. All programs are subject to change.The 2024.25 Classics Series is presented by the UNITED PERFORMING ARTS FUND and ROCKWELL AUTOMATION

Guest Artist Biographies

DASHON BURTON

Hailed as an artist “alight with the spirit of the music” (Boston Globe), threetime Grammy-winning bass-baritone Dashon Burton has built a vibrant career, performing regularly throughout the U.S. and Europe.

Burton’s 2024-25 season begins with Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 with the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl, led by Gustavo Dudamel. Highlights of the season include returns to the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra for his second season as artistic partner, featuring Mahler’s Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, Bach’s Ich habe genug, and Brahms’s Ein deutsches Requiem, conducted by Ken-David Masur. He makes his Boston Symphony subscription debut with Michael Tilson Thomas’s Walt Whitman Songs, conducted by Teddy Abrams, and his Toronto Symphony debut in Mozart’s Requiem under Jukka-Pekka Saraste. Additional performances include the Brahms-Glanert Serious Songs and Mozart’s Requiem with the St. Louis Symphony under Stéphane Denève, Mozart’s Requiem with the Minnesota Orchestra and Thomas Søndergård, and Handel’s Messiah with the National Symphony, led by Masaaki Suzuki.

During the 2023-24 season, Burton collaborated frequently with Michael Tilson Thomas, including performances of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 with the San Francisco Symphony and Copland’s Old American Songs with the New World Symphony. He also sang Bach’s Christmas Oratorio with the Washington Bach Consort, Handel’s Messiah with both the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the title role in Sweeney Todd at Vanderbilt University. With the Cleveland Orchestra, he appeared in a semi-staged production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute. As the Milwaukee Symphony’s artistic partner, Burton joined Ken-David Masur for three subscription weeks.

A multiple award-winning artist, Burton earned his second Grammy Award in 2021 for Best Classical Solo Vocal Album for his role in Dame Ethel Smyth’s The Prison with The Experiential Orchestra (Chandos). He won his first Grammy in 2013 as an original member of the groundbreaking ensemble Roomful of Teeth for their debut album of new commissions. In 2024, he earned his third Grammy for their latest recording, Rough Magic, featuring works by Caroline Shaw, William Brittelle, Peter Shin, and Eve Beglarian.

Burton’s discography also includes Songs of Struggle & Redemption: We Shall Overcome (Acis), the Grammy-nominated recording of Paul Moravec’s Sanctuary Road (Naxos), Holocaust, 1944 by Lori Laitman (Acis), and Caroline Shaw’s The Listeners with the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra. His album of spirituals received critical acclaim, with The New York Times calling it “profoundly moving…a beautiful and lovable disc.”

Burton holds a Bachelor of Music degree from Oberlin College and Conservatory and a Master of Music degree from Yale University’s Institute of Sacred Music. He is currently an assistant professor of voice at Vanderbilt University’s Blair School of Music.

SONYA HEADLAM

With a voice described as “golden” (Seen and Heard International), soprano Sonya Headlam enjoys a versatile career in ensemble and solo singing, and in repertoire spanning art song, opera, chamber music, concert works, and oratorio. She has performed with leading ensembles across the United States, including the New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, North Carolina Symphony, Apollo’s Fire, and New Jersey Symphony.

Celebrated for her heartfelt interpretations of Handel’s Messiah, Headlam devotes much of her career to performing works from the Western classical canon. She also explores music beyond the traditional repertoire, performing lesserknown works of the past alongside innovative contemporary compositions. This commitment is exemplified by her recent collaboration with the Raritan Players on a recording of songs by Ignatius Sancho and Reflections, a new composition by Trevor Weston based on Sancho’s words. Both recordings are anticipated to be released in 2025.

Additional recent highlights include Mozart’s Requiem with Downtown Voices and a program with the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra featuring music by Mozart and Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, under conductor Jeannette Sorrell, alongside New York Philharmonic principal clarinetist Anthony McGill. Headlam also premiered the role of the Caretaker in Luna Pearl Woolf’s Number Our Days: A Photographic Oratorio, at the new Perelman Performing Arts Center in New York City and performed Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians with the Bang on a Can All-Stars at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. In addition to these recent projects, past collaborations include performances of works by composers such as Ellen Reid, Tyshawn Sorey, and Julia Wolfe, reflecting her commitment to a diverse repertoire spanning both contemporary and traditional works.

A former full-time member of the Grammy-nominated Choir of Trinity Wall Street, Headlam credits this formative experience with having a lasting influence on her artistry. She holds a Doctor of Musical Arts degree from Rutgers University, where she was honored with the Michael Fardink Memorial Award.

Program notes by David Jensen

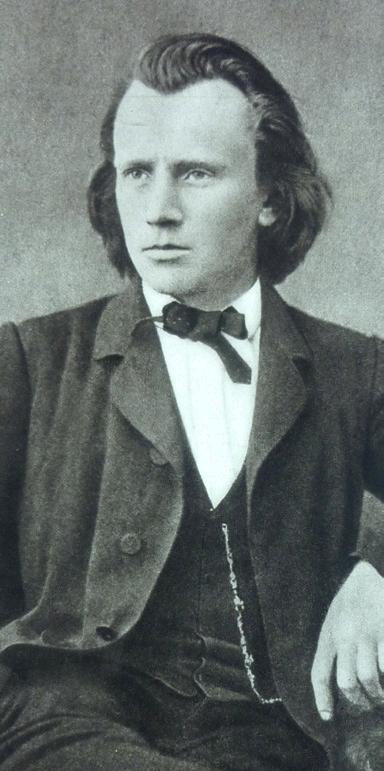

JOHANNES BRAHMS

Born 7 May 1833; Hamburg, Germany

Died 3 April 1897; Vienna, Austria

Ein deutsches Requiem [A German Requiem], Opus 45

Composed: 1857 – May 1868

First performance: 10 April 1868 (partial premiere); Johannes Brahms, conductor; Julius Stockhausen, baritone; Bremen Cathedral; 18 February 1869 (complete premiere); Carl Reinecke, conductor; Emilie Bellingrath-Wagner, soprano; Franz Krückl, baritone; Gewandhaus Orchestra

Last MSO performance: 30 March 2019; Eun Sun Kim, conductor; Tara Erraught, soprano; Stephen Powell, baritone

Instrumentation: 2 flutes; piccolo; 2 oboes; 2 clarinets; 2 bassoons; contrabassoon; 4 horns; 2 trumpets; 3 trombones; tuba; timpani; 2 harps; organ; strings

Approximate duration: 68 minutes

Brahms’s life was not a particularly happy one. The son of a seamstress and a semi-professional musician, his upbringing was troubled by his family’s economic instability. As a child, his talents were sensational — his friendship with the violinist Joseph Joachim, who immediately recognized his miraculous instinct for composition, brought him into contact with the Schumanns in 1853. But plagued by a tendency toward perfectionism and self-doubt, the extravagant accolades Robert printed in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik that October burdened Brahms, writing to Schumann a few weeks later that his praise would “arouse such extraordinary expectations of my achievements by the public that I don’t know how I can begin to fulfill them even somewhat.”

Robert’s suicide attempt and hospitalization in a private sanatorium, followed by his untimely death two years later in 1856, left Brahms bereft. He returned to Düsseldorf to help manage the family’s affairs, and the attention he subsequently lavished upon Clara bred in him a lifelong ardor that would never find its consummation. There is evidence that Brahms had begun sketching a “cantata of mourning” in the year following Robert’s death, but it was his own mother’s passing in the winter of 1865 that provided him with the emotional impetus to begin planning in earnest a large-scale choral work devoted to articulating his attitude toward death. The centuries-old tradition of setting the requiem mass had, by that point, established a standardized Latin text as the de facto model for the genre, but Brahms culled the language for his interpretation from Martin Luther’s German translation of the Bible, pointing unequivocally to his categorically humanistic (in contrast to a strictly Catholic) perspective. Brahms even explained to Carl Reinthaler, director of music at Bremen Cathedral (where a partial premiere of the Requiem took place in April 1868), that it could just as well have been called Ein menschliches Requiem (“A Human Requiem”). Preoccupied with consoling the living as opposed to simply honoring the dead, the very beginning — its shadowy hues marked by the absence of violins — unfolds with a line from the Beatitudes: “Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted.”

Four of the seven movements are written for purely choral forces, with the third and sixth calling for a solo baritone and the fifth for a soprano, and the influence of the choral music of

the preceding three centuries is evidenced by the brilliant fugues which conclude the second, third, and sixth. The second (a funeral march) and sixth (the apostle Paul’s reflection on the resurrection) constitute the lengthiest and most dramatic segments, and the music reaches its emotional summit in the fourth, which is rightfully cherished as some of the most breathtaking writing in the vocal repertoire. Architecturally, the German Requiem is fashioned as an arch structure, and as the seventh movement reprises the music of the first (harps play at the close of both), a passage from the Book of Revelation (“Blessed are the dead”) draws the requiem to a close with the very same word with which it began.