TCHAIKOVSKY NO. 5

Friday, October 21, 2022 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, October 22, 2022 at 7:30 pm

ALLEN-BRADLEY HALL

Jader Bignamini, conductor

Blake Pouliot, violin

SAMUEL COLERIDGE-TAYLOR

Ballade in A minor, Opus 33

NICCOLÒ PAGANINI

Violin Concerto No. 1 in D major, Opus 6

I. Allegro maestoso

II. Adagio

III. Rondo: Allegro spiritoso

Blake Pouliot, violin

IN TERMISSION

PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY

Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Opus 64

I. Andante – Allegro con anima

II. Andante cantabile con alcuna licenza

III. Valse: Allegro moderato

IV. Finale: Andante maestoso – Allegro vivace

The 2022.23 Classics Series is presented by the UNITED PERFORMING ARTS FUND.

The length of this concert is approximately 2 hours.

Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra can be heard on Telarc, Koss Classics, Pro Arte, AVIE, and Vox/Turnabout recordings. MSO Classics recordings (digital only) available on iTunes and at mso.org. MSO Binaural recordings (digital only) available at mso.org.

MILWAUKEE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 37

Guest Artist Biographies

JADER BIGNAMINI

Jader Bignamini is the music director of the Detroit Symphony. He led his first full season of concerts in the 2021.22 season, which included a tour to Florida in January 2022. Bignamini continues as resident conductor of the Orchestra Sinfonica la Verdi, following his appointment as assistant conductor in 2010 by Riccardo Chailly.

In summer 2021, Bignamini led triumphant performances of Turandot at the Arena di Verona with Anna Netrebko and Yusiv Eyvazov, as well as a staged production of Rossini’s Stabat Mater at the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro.

Recent highlights include debuts with the Metropolitan Opera, Vienna State Opera, and Dutch National Opera conducting Madama Butterfly, Luisa Miller, and La Forza del Destino at Oper Frankfurt, Cavalleria rusticana at Michigan Opera Theatre, La bohème at Santa Fe Opera, and La Traviata in Tokyo directed by Sofia Coppola. On the concert stage, he has lead the Dallas and Milwaukee symphonies, Minnesota Orchestra, Slovenian and Freiburg philharmonic orchestras, Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz, and Mannheim National Theater Orchestra.

Bignamini has conducted Manon Lescaut at the Bolshoi, La Traviata at Bayerische Staatsoper, Eugene Onegin at Stadttheater Klagenfurt, Turandot at the Teatro Filarmonica, Il Trovatore at Rome’s Teatro dell’Opera, the opening concert of the Orchestra Filarmonica del Teatro Comunale di Bologna conducting Carmina burana; La bohème at the Municipal de São Paulo and La Fenice; L’Elisir d’Amore in Ancona; Tosca at the Comunale di Bologna; La Forza del Destino at the Verdi Festival in Parma; La bohème, Cavalleria Rusticana, and L’Amor Brujo at Teatro Filarmonico di Verona; Aida at Rome’s Teatro dell’Opera; Madama Butterfly at La Fenice. In 2013, Bignamini assisted Riccardo Chailly on concerts of Mahler’s Eighth Symphony in Milan. He made his concert debut at La Scala in 2015.

Bignamini was born in Crema and studied at the Piacenza Music Conservatory.

38 MILWAUKEE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

Program notes by J. Mark Baker

Coleridge-Taylor’s lush Ballade opens tonight’s concert, after which a virtuoso Paganini concerto puts guest violinist Blake Pouliot through his paces.

Following intermission, Tchaikovsky’s soul-stirring symphony showcases the full orchestra.

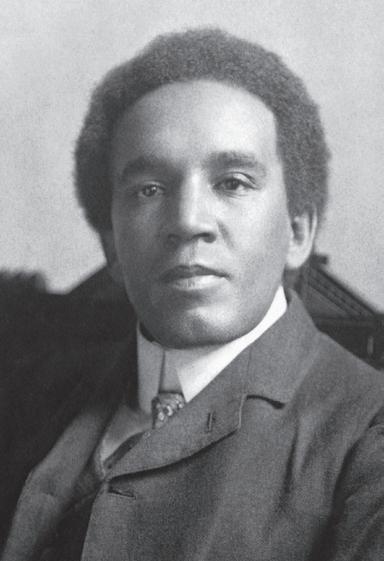

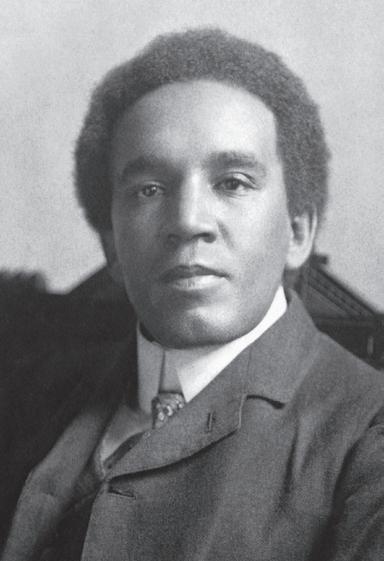

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Born 15 August 1875; London, England

Died 1 September 1912; Croydon, England

Ballade in A minor, Opus 33

Composed: 1898

First performance: 12 September 1898; Gloucester, England

Last MSO performance: February 2003;

Grant Llewellyn, conductor

Instrumentation: 2 flutes; piccolo; 2 oboes; 2 clarinets; 2 bassoons; 4 horns; 2 trumpets; 2 trombones; bass trombone; tuba; timpani; percussion (cymbals); strings

Approximate duration: 13 minutes

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor – his mother was English and his father was a physician from Sierra Leone – studied at London’s Royal College of Music (1890-97). A violinist and singer as well as a composer (his teacher was the revered Charles Villers Stanford) during his time there, he wrote choral anthems, chamber music, and songs. He is best remembered for his 1898 cantata Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, a setting of Longfellow’s poem, once popular for its exotic colorings and its accessibility to amateur choral societies.

The A-minor Ballade dates from the same time as Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast. Coleridge-Taylor had graduated from the Royal College just a year earlier. When Sir Edward Elgar was asked to write a piece for the Three Choirs Festival – it was in Gloucester that year – he begged off, citing his too-full schedule. “I wish, wish, wish,” he wrote the committee, “you would ask ColeridgeTaylor to do it. He still wants recognition, and he is far and away the cleverest fellow going amongst the young men.”

In this work, and numerous others, one senses the influences of Dvořák, Tchaikovsky, Grieg – and that of his mentor, Elgar. The warm string melodies are plush and elegant, but Coleridge-Taylor does not shy away from high-spirited passages of brass and timpani. In all, it’s a brief but cogent early harbinger of the luxuriant music that would flow from his pen in the years to come.

MILWAUKEE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 41

Niccolò Paganini

Born 27 October 1782; Genoa, Italy

Died 27 May 1840; Nice, France

Violin Concerto No. 1 in D major, Opus 6

Composed: c1817

First performance: 31 March 1819; Naples, Italy

Last MSO performance: October 2004; Lu Jia, conductor; Hilary Hahn, violin

Instrumentation: 2 flutes; 2 oboes; 2 clarinets; bassoon; contrabassoon; 2 horns; 3 trombones; timpani; percussion (bass drum, cymbals); strings

Approximate duration: 35 minutes

Niccolò Paganini is arguably the most famous violinist of all time. Possessing an impeccable technique and extraordinary personal magnetism, it was Paganini who first drew attention to the notion of virtuosity as an artistic element. His unprecedented technical magic on the instrument – including the use of left-hand pizzicato, double-stop harmonics, “ricochet” bowings, and a generally audacious approach to performance – influenced successive generations of players.

His most significant impact, though, was on the composers – Liszt, Schumann, Chopin, Berlioz – who were inspired to achieve, through technical challenge, greater expression in their own compositions. Brahms, Rachmaninoff, Lutoslawski, et al. were moved to write sets of variations of his Caprice, Opus 1, No. 24 – one of the best-known compositions for solo violin. Paganini launches his first concerto with a bombastic D-major chord, then there’s protracted orchestral introduction – often circus-like, with laugh-out-loud humor – before the soloist finally makes his entrance. The material presented by the orchestra is then reinterpreted and expanded upon, as virtuoso fireworks alternate with meltingly lyrical passages. As this extended Allegro maestoso nears its end, the orchestra hammers to a dramatic pause, and we hear a cadenza – an opportunity for the soloist to show us his range of technique and musicality. Paganini would have improvised this passage, and never wrote down any version of what he might have played.

The Adagio is set in the relative key of B minor. Following a brief introduction, the soloist enters – like an operatic diva – with an expressive melody that is soon repeated an octave lower. At one point, pizzicato strings imitate the sound of a guitar (another instrument mastered by Paganini), lending the atmosphere of an amorous serenade. Though he was the epitome of technical léger de main, Paganini likewise could spin out a cantabile phrase to melt the heart. Friedrich Wieck, Clara Schumann’s father, once gushed, “Never did I hear a singer who touched me as deeply as an Adagio played by Paganini. Never was there an artist who was equally great and incomparable in so many genres.”

The carnival atmosphere returns in the closing rondo, in which the dancing main tune alternates with contrasting episodes. The movement is a virtual compendium of Paganini’s virtuoso tricks – ricochet bowing, double-stopped harmonics, flashy finger work, and moments of humor, among others. Reputedly, this Allegro spiritoso is one of the most challenging movements in the solo violinist’s repertoire, and brings this engaging work to a delightful close.

42 MILWAUKEE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born 7 May 1840; Kamsko-Votkinsk, Russia

Died 6 November 1893; St. Petersburg, Russia

Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Opus 64

Composed: 1888

First performance: 17 November 1888; St. Petersburg, Russia

Last MSO performance: November 2017; Karina Canellakis, conductor

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo); 2 oboes; 2 clarinets; 2 bassoons; 4 horns; 2 trumpets; 3 trombones; tuba; timpani; strings

Approximate duration: 50 minutes

In December 1887, Tchaikovsky set out on his first foreign tour as a conductor – leading concerts in Leipzig, Hamburg, Berlin, and Prague – and meeting Brahms and Grieg along the way. After concerts in Paris and London, he returned to Russia in April 1888, where he began work on the fifth of his six symphonies. He completed his Opus 64 on 26 August 1888, and it was given its first performance three months later, with Tchaikovsky conducting. The composer’s second piano concerto (1880) was on the same program.

The four movements of the Symphony No. 5 are cyclic, unified by a “motto theme” (or motif) that is first stated at the beginning of the work. Most commentators agree that this represents the idea of Fate, referred to by the composer in his early writings about the piece.

The symphony begins quietly and funereally, with the Fate motif played by the clarinets. For the main part of the first movement, the tempo is faster and the themes – taut and energetic, passionate and sighing – are built to a dynamic climax. This highly vigorous movement ends with a barely audible rumble from the low strings, bassoons, and timpani.

The Andante cantabile is vintage Tchaikovsky: well-crafted, colorfully orchestrated, with a languid horn melody that is one of the best-known in the symphonic repertoire. In the middle of the movement, the Fate motif interrupts noisily. In place of a scherzo, the third movement is a waltz; its trio, however, exhibits the playful character of a scherzo. The Fate theme is given a softpedal treatment by clarinets and bassoons near the end of the movement.

The finale begins with the Fate motif, this time transposed from E minor to E major. A vigorous sonata form movement unfolds. “If Beethoven’s Fifth is Fate knocking at the door, Tchaikovsky’s Fifth is Fate trying to get out,” wrote an early commentator. Indeed, the Fate motif marches forward in grand array: fortissimo, broad, majestic, in a major key. That’s not the end, however, for the music then dashes headlong into a presto, broadening again for the symphony’s triumphant final moments.

MILWAUKEE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 43