18 minute read

New feature – Tip of the Month Applying for draw tags

OUTDOOR TIPS OF THE MONTH

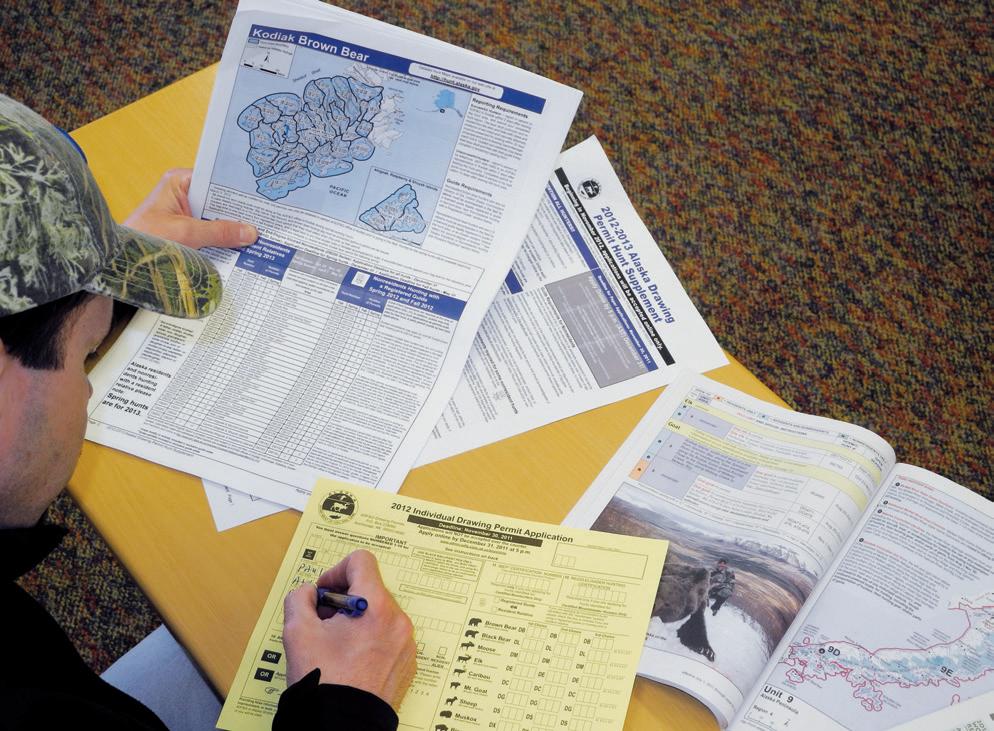

Some of Alaska’s most epic hunts are only obtainable through the state Department of Fish and Game’s draw lottery system. Our Arctic sportsman Paul Atkins applies for several of these each year – nowadays digitally – so he understands the process, along with the frustration of often not

being drawn. (PAUL D. ATKINS)

TALKING TAGS FOR DRAW HUNTS

Editor’s note: In this new column, our Paul Atkins will offer sportsmen and -women tips for making the most out of their Alaska fishing or hunting adventure. With the application period opening this month, he details putting in for draw tags.

BY PAUL D. ATKINS

August, September and October have come and gone. Your freezer is full of moose and caribou and you remember what great hunts both were. Rifles are cleaned and put away, gear has been stored and you’re thankful for the hunting you did get to do. It’s time to settle in for winter.

For most Alaska hunters, this is the cycle of life, but if you’re like me and hunting is truly your passion, then you’re already starting to think about next season and what you will be hunting – or would like to hunt. Whether we live here in Alaska or in the Lower 48, many of us find ourselves wanting, or sometimes wishing, we could hunt a particular species in a particular area. What might be common for some might be a dream for others, whether it’s Dall sheep in the Chugach, goats in Southeast or maybe a coveted brown bear on Kodiak. All are obtainable with a little luck, while some require long-term planning. However, some of these hunts require a certain tag that can only be obtained through a drawing of some kind.

LUCK OF THE DRAW Each year the state of Alaska has a permit drawing. As in most states, hunters can apply for certain tags to hunt a particular species in a specific

area at a certain time. Some are easy to draw, while others are downright difficult. I personally put in for several hunts each year hoping to finally luck out and draw that special tag. Then, when spring rolls around, I anxiously check the computer to see if I drew it.

Here’s how it works: Each year the Alaska Department of Fish and Game will allow a certain number or permits to be applied for and obtained by hunters, both resident and nonresident. The number of tags allotted is based on the animal population surveys that biologists perform each year. These surveys determine the number of animals that

You can apply for a 2022 draw hunt tag from November 1 to December 15. If you’re lucky, you just may score a chance to harvest the bull, bear or billy of your

dreams. (PAUL D. ATKINS) H ere are a few strategies when it comes to applying: • Look over all the permits offered and find what interests you. You can even look at maps on ADFG’s website (hunt.alaska.gov) to get a better perspective. • Choose a hunt with high permit numbers. It has been my experience that you can’t go wrong with most hunts here in the state, but some are a lot more challenging than others. • Choose as many species as you feel comfortable applying for and can afford. • Make sure your application is complete. Get the correct information in the correct boxes, type in the correct license number and then pay the fee. Accurate information will result in a better chance for being successful. • Apply early. If there is a mistake, ADFG will contact you and help you correct it. • Don’t give up on the application process. If you don’t draw this year, try again the next; you never know what can happen, and besides, you won’t get the tag unless you put in for it! PA

can be harvested from a certain area. They then allow hunters to apply for these permits through a drawing.

The application period for applying for these hunts runs from November 1 through December 15 – based on last year’s information – with the results being posted usually in late February. The drawing is species-specific and unitspecific. All Alaska big game animals are included, with some of the more coveted tags being for Kodiak brown bear, Dall sheep, mountain goats, muskox and plains buffalo – the one that eluded me for years. Moose are also included, along with caribou and grizzly in some areas.

HOW TO APPLY Applying takes place online and is easy to navigate. Each submitter must have a current Alaska hunting license to apply. If you do get lucky and draw a tag, you will be ineligible to hunt that species in the same area next year. Hunters who are successful may only receive one permit per species and the hunts are non-transferable. These applications do cost money, but it’s reasonably cheap compared to most states (ranging from $5 to $20 per hunt number).

Nonresidents have a few more restrictions than do locals, particularly when it comes to certain species. Outof-state hunters must have a guide when it comes to brown bear, grizzly, Dall sheep and goat hunts; however, moose and caribou do not require a guide, something to remember when applying for certain tags that will take you to some remote wilderness.

It’s suggested that if you are applying for a permit requiring a guide, you should do so long before the application period begins. This way you can be assured the guide is available if you do draw. Hunters should only select reputable guides registered with the state

PREPARE ACCORDINGLY Hunters who plan to apply for a permit that doesn’t require a guide still need to do their homework. Most of these hunts will require a transporter of some kind, and whether going by boat or plane, you will need to be in contact with someone who services the area. Most transporters book early and often; if you’re lucky enough to get a permit, you’ll need their help.

Remember that a transporter is not a guide; their job is to get you safely from point A to point B. All transporters are not created equally, so make sure you choose carefully.

Also, don’t forget that if you are 16 years or older you must have completed a basic hunter education course to hunt in the state of Alaska. Additionally, some areas require a bowhunting education course. These archery-only areas are usually close to roads or near a town.

For more, go to ADFG’s website, which can be found at hunt.alaska.gov. To those who are successful, I wish you the best of luck and another great year of hunting in Alaska. ASJ

Editor’s note: Got a question for Paul to answer about an Alaska hunting or fishing trip? Send it to editor Chris Cocoles at ccocoles@media-inc.com.

WHERE BIRDS ARE ALSO BIG GAME

ALASKA ONE OF FEW STATES WHERE SANDHILL CRANES, TUNDRA SWANS CAN BE HUNTED

BY PAUL D. ATKINS

As I think back on my time in the Arctic, there were many ups and downs, joys and discomforts, highs and lows – and just about everything in between.

Killing a big bear or moose were high on my lists, but there was also pleasure in the little things, such as how to pack for camp, gathering wood as soon as the bush pilot dropped us off, learning how to skin and gut a caribou Eskimo style – horns down, belly up.

Like most people who spend significant time up here, I loved it all, but there were surprises too; one in particular completely caught me off guard, which was my love for bird hunting. Here is one of those tales from long ago, with a little how-to advice thrown in there for fun.

AS WE SLOWLY MOTORED forward, the black water began to swirl, bubble and give off a gaseous smell that seemed to be seeping up from the tundra and into the water. The narrow and winding slough went on forever and resembled a snake heading into an open field. But this wasn’t a field; it was the vast space of an Arctic marsh and we were looking for birds.

Like I did, you’ll discover that late-season waterfowl hunting can be tough in Northwest Alaska. The ducks and geese you found back in late August and early September are but a memory now. It was great while it lasted, though; the huge flocks moved in like waves and settled on the various lakes and ponds that make up the area. It was some of the best bird hunting in years, when you shot more boxes of shells than you can ever remember.

This was early October now and, as promised, cold weather took up residency above the Arctic Circle. The willows were a deep dark brown and the ice-lined banks of the river a telltale sign of what is getting ready to happen. Sheets of frozen water skimmed the surface in some areas, and they made a crackle sound as the boat moved up the slough.

The seasons don’t last too long up here, but they’re not supposed to either. With the change most birds have packed up and headed south; or at least the smart ones have. But until you go and look you can never be sure.

For some of us the hunter’s horn blows constantly and we do what we must do, go whenever we can and hunt whatever is available, especially when some of the bigger rivers and lakes prevent us from chasing the big boys in bad weather.

You know caribou are out there making their migration, but you can’t get to them when you need to. So, you go bird hunting instead.

WHERE BIRDS ARE ALSO BIG GAME

Some of Arctic Alaska’s most underrated hunting opportunities are for majestic birds like tundra swans and sandhill cranes. Though it does take some effort, swans leave the water with grace and speed. And often, just as soon as one group leaves, another takes its place. (PAUL D. ATKINS)

Just as with Lower 48 waterfowl, setting up decoys – either along a river or in an adjacent lake – is essential for bringing in the big birds. It gives them a sense that all is normal – or at least makes them a little more comfortable. (PAUL D. ATKINS)

ONE OF THE BEST things about living in the Arctic are those “best-kept secrets” – those “small places” where a hunter can get away for a few hours. If it all goes well, then maybe you’ll get some shooting in. That was what we were doing on this first day of October.

To be honest, I’ve never been much of a waterfowler. Growing up in the Midwest, we just didn’t do it; I certainly didn’t, anyway. But when I came to Alaska many years ago, I met several people who did, and they were very good at it.

My good friend Lew is one of those people. Over the years Lew has taken me along on just about every “bird” outing we’ve had. He’s taught me the essentials of waterfowl hunting and the art of chasing the different species we have here in Northwest Alaska. I’ve learned plenty during that time, including how to set decoys, build an effective blind and – even though I’m far from perfect – do some calling.

We’ve taken a ton of ducks over the years, and it has been a blast, but it has always been the bigger, more challenging birds that have truly inspired us to further our pursuits in the Arctic marshlands. I’m talking about the mighty sandhill crane and the always tough tundra swan.

The toughest birds to bring down aren’t always necessarily the small, fast flyers – like pintail and greenwing teal. Sometimes it’s the bigger, more massive birds that will try your patience. For one thing, they’re smart, so getting close enough to shoot or even get a chance at one of them can be as frustrating as hunting any big game animal. I know it’s that way for me, as I’ve been trying for years.

LET’S BEGIN WITH THE sandhill crane. These magnificent birds are huge. There have been times while glassing the tundra for caribou that I’ve mistaken them for the deer family member. This is not something I tell many people, but from a far distance, their big bodies, long necks and head look more like a big game animal than a bird.

These incredible creatures are Alaska’s largest – or I should say tallest? – feathered game birds. They can be found in the marshes and swamps located throughout Northwest Alaska. Light brown in color and with a tremendous wingspan, sandhill cranes are numerous here in the fall. They’ll stop off before heading south on the Pacific Flyway. It’s during this time that we get to see them and try our luck at harvesting a few.

As far as hunting them, spot and stalk are two methods, but their eyesight is keen and you’ll usually get busted once you decide to leave and make your move.

I’ve found that blinds are the most effective. Good concealment – whether in a homemade job or a commercially bought blind – will help seal their fate, especially if there are numerous birds in the area.

Sometimes called the “Sunday turkey” in parts of Alaska, sandhill cranes make excellent eating, and many refer to them as the “filet mignon” of the sky.

Whatever technique you choose to hunt sandhills, you’ll need to make sure you have enough gun and are using a quality steel shot to be successful. A 12-gauge with a minimum of size 2 shot or BB has worked best in my experience (I prefer the latter).

Alaska does have a limit when it comes to cranes, so be sure to check the regulations. Up here in the Arctic it differs from other places, and you are allowed three per day and nine in possession. You must have a valid hunting license and all the proper stamps.

AS FAR AS SWANS go, there are two species in Alaska, the trumpeter and his smaller cousin, the tundra. The trumpeter is the largest member of the waterfowl family and cannot be hunted, but the tundra variety, which is smaller – about two-thirds the size of a trumpeter – can be, even though they’re hard to distinguish at times.

Besides size, mature tundra swans have a distinguishable yellow spot on their black bill near their eye, but it’s tough to see while in flight.

Seeing a pair of sandhill cranes in flight is incredible. These huge birds have tremendous wingspans and their loud, rolling musical cries are very recognizable.

(PAUL D. ATKINS)

Much like hunting cranes, these birds are big and extremely hard to bring down. They’re smart too and seem to outwit more hunters than any other bird. They have phenomenal eyesight and can see even the slightest movement or color disfiguration when you’re trying to hide yourself, even if you’re in a blind. Again, concealment with good camouflage is the key in hopes of catching swans that are working the water and moving from place to place.

Swan hunting isn’t for everyone and there are some who find it a little taboo. These magnificent birds are no doubt beautiful, and for some people it isn’t something they want to do or participate in. However, they’re great game birds

Swans are numerous in this region and will stay as long as there is open water. These birds decided to stick around after the first snow had fallen and ice started to form. (LEW PAGEL)

Having a dog to gather your birds is a big benefit on any waterfowl hunt, but if you don’t have a retriever, chest waders will work for bringing in your bird. Author Paul Atkins says his waterfowl hunting pal Lew Pagel is proficient at this. (PAUL D. ATKINS) that produce some of the finest table fare in the outdoor world. If the sandhill crane is the filet mignon of the sky, then the tundra swan is the porterhouse!

In my opinion and even Lew’s, bringing a swan down is one of the tougher challenges you’ll encounter as a bird hunter. Sloshing through the delta trying to get to where they are without being noticed is the biggest test. It’s been our experience that the best chance at harvesting one is to find a lake back from the main river where they’re holding up, then build a blind near that area in hopes of catching a “bevy” – or a group – making their way to a new location.

Swans have thick skin and, like cranes, you need to make sure you have enough firepower and are proficient at shooting to bring one down. They also tend to fly high; those that don’t are still pretty tough to land on the tundra if you’re not a decent shot. As with cranes, you’ll need the proper licenses and a Federal stamp, and you’ll want to check the regulations for open units, as you can only hunt swans in four game units along the Bering and

Laydown blinds work great in the Arctic. Simply find a place close to water and lay down. If it’s a slow day, you can enjoy a bit of a rest too. (PAUL D. ATKINS)

Chukchi Seas. The annual limit is three and you must have a specific swan tag to keep track of your harvest for reporting purposes.

AS WE EASED INTO the narrow channel, the willows began to thin, making both visibility and hearing better. I turned to Lew and said, “Do you hear that?” An orchestra of thousands of swans mixed with the occasional sound of ducks could be heard in the distance. It was like an early Christmas present had come to the Arctic, with seemingly endless white specks dotting the adjacent lakes.

We made our way to shore, anchored the boat and then glassed the big lake where all the action was. With thousands of birds seated on the water, we wanted to get to them as fast as possible. However, we knew that we needed to have a plan in order to limit the number of trips back and forth to the boat. We did so by grabbing as much gear as possible, including decoys, shotguns, food, water and as many shotgun shells as we could carry.

Finally, with waders secured we bundled up and made our way towards the willow-infested bank that lined the lake. This was going to be wild!

With Lew buried in his laydown blind and me hidden in a willow-induced cone, we waited for the action. It was slow going at first, but we knew with patience it would eventually happen.

While we waited, I grabbed my binoculars and noticed something across the big lake. It was a bull moose that looked to be chasing two cows. I hollered at Lew and said, “Do you see that?” He nodded his head.

Even though we both had moose tags in our pockets, we had more important things to do, which was to try our luck at getting a swan or two. It was moments later that it happened. A group of four birds left the water and started their accent in our direction. Now, I’d never killed a swan, even though I tried and missed plenty of times. Lew, on the other hand, had taken several, but I could sense his excitement too as they made their way towards us.

THE MOMENT OF TRUTH is always fun, especially when the sound of an enormous wing flap is approaching. Timing is everything, and we sprung from our hiding places and fired at the same time.

The sound of our shotguns echoed

There is never a dull day in the Arctic, especially when the birds are flying. On this trip Pagel and Atkins were able to take an assortment of waterfowl, including this sandhill crane and a variety of ducks.

Swans are a formidable quarry, but can provide some of the best hunting in the outdoor world. In Alaska, it’s an autumn waterfowling experience like no other. (PAUL D. ATKINS) across the delta as two large birds hit the tundra with a loud surprising thump. I was actually amazed at this and for a moment was glad they didn’t land on top of me. Either way, I had just harvested my first swan.

As I walked up to my bird, it was beautiful and surreal all at the same time. I just couldn’t believe how big this guy actually was.

Swans and cranes are abundant here in Alaska, especially in the northwest part of the state. Hunting them on a cold Arctic day is truly underrated, and in my opinion rivals any big game hunt. But taking them down is a totally different story. ASJ

Editor’s note: Paul Atkins is an outdoor writer and author from Kotzebue, Alaska. He’s had hundreds of articles published on big game hunting in Alaska and throughout North America and Africa, plus surviving in the Arctic. His new book Atkins’ Alaska is available on Amazon and everywhere good books are sold. It can also be ordered through paulatkinsoutdoors.com. If you want an autographed copy, contact Paul at atkinsoutdoors@gmail.com.