SEPTEMBER 2023 - VOL 84 | NO. 5 The Voice for Missouri Outdoors CONSERVATION FEDERATION SPECIAL WETLANDS EDITION

PRESERVING OUR CONSERVATION HERITAGE

For more than eighty-seven years, the Conservation Federation of Missouri (CFM) has served as “The Voice for Missouri Outdoors.” Join in our efforts to secure our stronghold as advocates for our state’s wildlife and natural resources by becoming a dedicated member of our Founders Circle.

Your contribution will play an influential role in preserving Missouri’s rich outdoor heritage.

Each year, earnings from the endowment will be used to support CFM’s education and advocacy efforts. Special recognition will be given to those who reach each level of giving. Additionally, memberships will be recognized at our annual Convention.

Make your contribution today, to preserving our state’s conservation legacy.

2 CONSERVATION FEDERATION FOUNDERS CIRCLE For more information contact Michelle at 573-634-2322 Ext. 104 or mgabelsberger@confedmo.org Founders Circle Levels Bronze - $5,000 to $9,999 Silver - $10,000 to $34,999 Gold - $35,000 to $74,999 Diamond - $75,000 or More Bronze Level Zach Morris-2022 David Urich-2022 Mike Schallon-2023 Liz Cook-2023 Gene Gardner-2023

Missouri's Cherished Wetlands

Welcome to the Special Wetlands Edition of the Conservation Federation magazine. This special edition is the culmination and work of many dedicated conservationists across Missouri and beyond. I hope you take the time to read all these articles and come away with a greater appreciation of these fragile ecosystems.

This journey started in our Wetlands and Waterfowl Resource Advisory Committee several years ago. It incubated and grew into the Wetlands Summit CFM hosted in February 2023 at Lodge of the Four Seasons. The expertise of the hundreds of resource professionals attending from many aspects of conservation and natural resources was inspiring. The need to share this information and capture our thoughts from that gathering became apparent and necessary.

I hope to reflect on these three days we spent together at the Summit, which proved to be a critical turning point in the wetlands and waterfowl management practices for decades. As CFM members, we should feel good about bringing citizens together who use, enhance, and protect these cherished lands. This is at the heart and soul of our worthwhile mission.

With cutting-edge science and technology, how we manage these systems is changing more rapidly than we can comprehend or keep up with. This rings true in many aspects of our lives, especially in conservation and the outdoors. In retrospect, CFM has only been around for 88 years. What will it look like in the next 88 years and beyond?

One of the highlights of the Summit for me was to get to meet the legendary Lee Fredrickson. Check out the sidebar on Page 30, which outlines the honor we bestowed upon him. It’s truly remarkable for a person to work at over 300 national wildlife refuges and state and private wetlands in all 50 states. He mentored over 75 graduate students as well. Talk about quite the ripple effect he will have for generations to come. His dinner speech was remarkable and legendary.

I want to thank the Missouri Wetlands Summit Planning Team once again. Many of them authored articles for the edition.

This committee put hours and days into their presentations and worked through logistics, topics, tiny details, and much more. Many are unpaid volunteers for CFM, some modern-day legends in my book, mentors to many, and a few characters and jokesters mixed in for good measure! However, the thing that rings true in all of them is their passion.

So where do we go from here? There certainly is no time to rest on our laurels. We must continue to forge ahead, pivot, adapt, and change in the name of science. Otherwise, we will be left behind, and these precious resources and species will be gone forever.

It was very educational for me to put this Special Wetlands Edition together for you. I hope it remains a resource document for years to come. Please put it in your magazine rack at your waterfowl camp, give a copy to a young outdoor enthusiast, or stick it on a shelf for someone to pull out and read long after your earthly sun rises and sets in the outdoors have passed. Enjoy!

Yours in Conservation,

Tyler Schwartze CFM Executive Director, Editor

SEPTEMBER - 2023 3

Director’s Message

Waterfowl hunting is just one of the many joys that we can experience in our wetlands in Missouri –

(Photo: Zach Morris)

CONTENTS

Conservation Federation

September 2023 - V84 No. 5

OFFICERS

Zach Morris - President

Bill Kirgan - President Elect

Ginny Wallace -Vice President

Benjamin Runge - Secretary

Bill Lockwood - Treasurer

STAFF

Tyler Schwartze - Executive Director, Editor

Micaela Haymaker - Director of Operations

Michelle Gabelsberger - Membership Manager

Wetlands Need People!

Partnerships - A Necessity for Aquatic Systems Conservations

National Partnerships Help Guide a Small Shorebirds Road to Recovery

Our Beloved Brazen Beaver

Learning to "Think Like a Wetland"

Moist Soil Management: Just Say No to Corn!

Wetlands, Waterfowl, and the Missouri Model

Cultivating the Next Generation of Conservation Professionals: A Natural Connection

Wetlands Benefit Everyone

Amphibians to Waterfowl: Conserving the Spectrum of Missouri's Wetland Biodiversity

Missouri's Rivers of Grass

Digging Up the Dirt on Burrowing Crayfish

The Land Learning Foundation

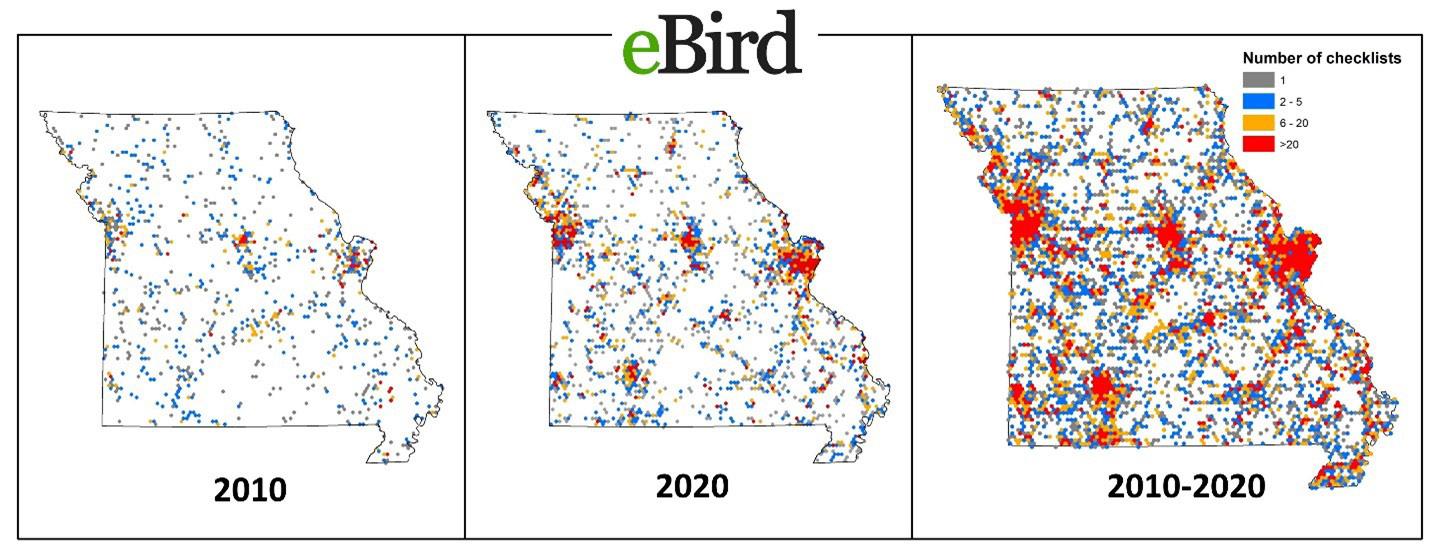

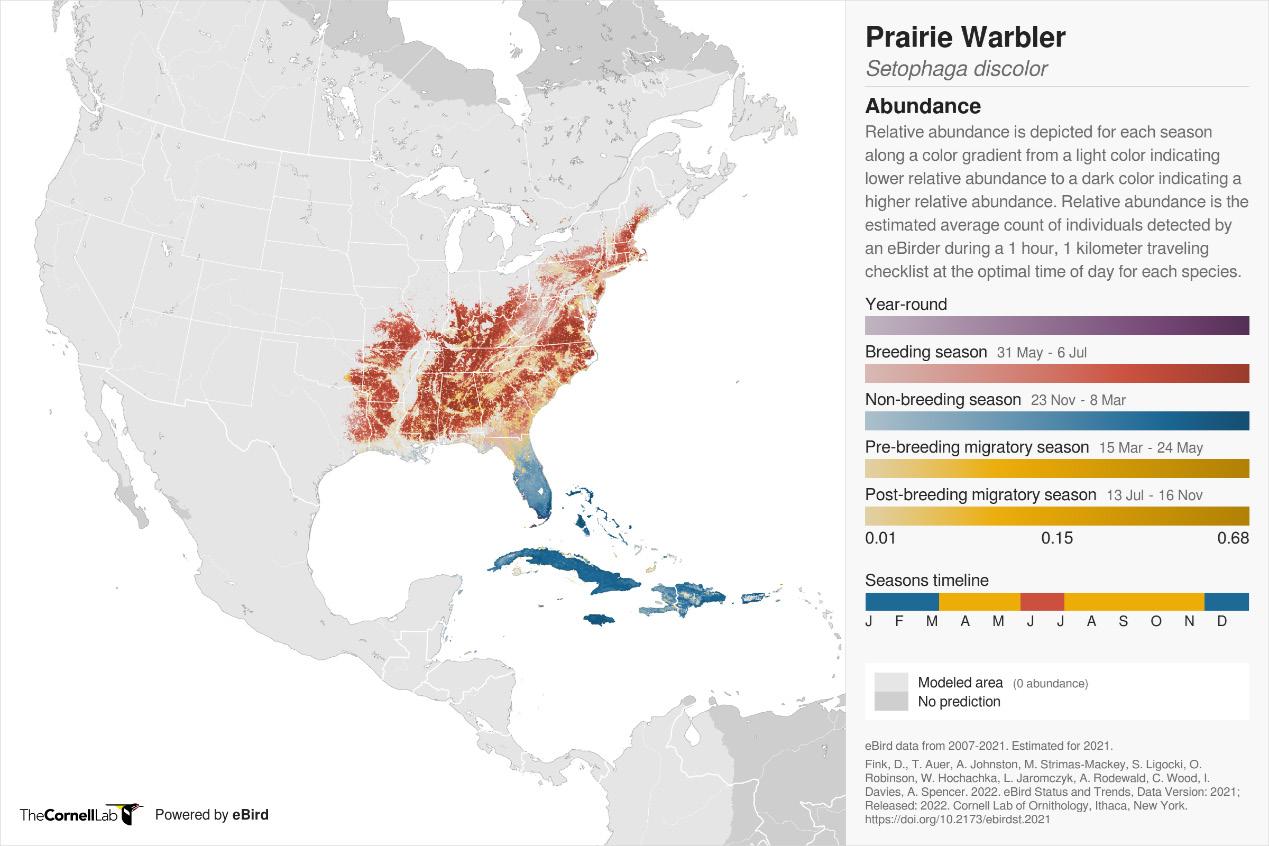

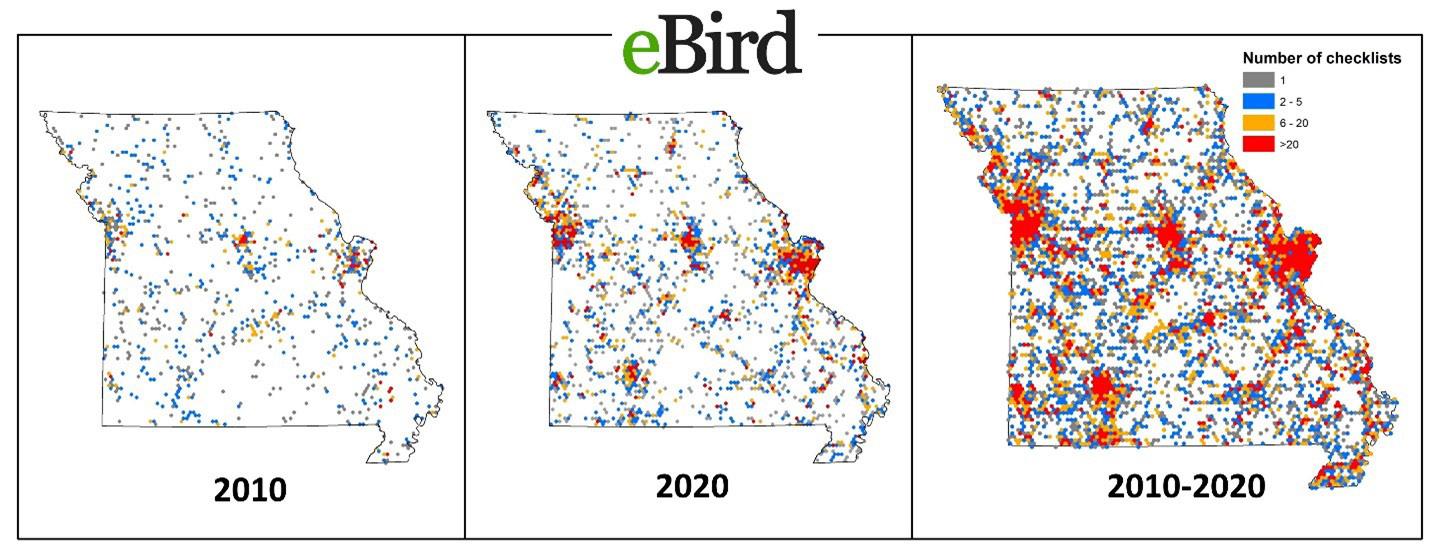

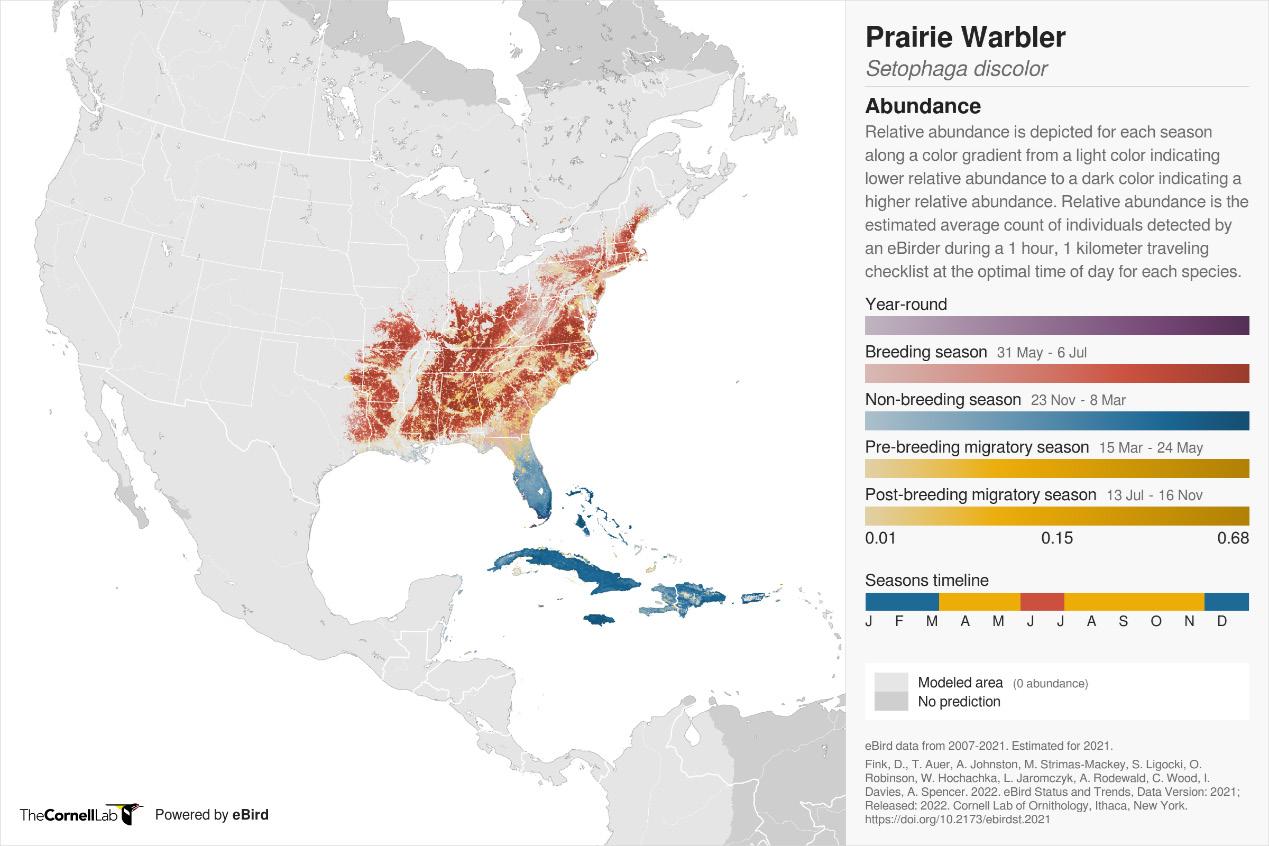

Birders and Wetlands: A Data-Driven Love Story

Native Aquatic Gardening

Schedule

Rabbit Research

Nick Darling - Education and Communications Coordinator

Tricia Ely - Development & Events Coordinator

Joan VanderFeltz - Administrative Assistant

Emma Kessinger - Creative Director

ABOUT THE MAGAZINE

CFM Mission: To ensure conservation of Missouri’s wildlife and natural resources, and preservation of our state’s rich outdoor heritage through advocacy, education and partnerships.

Conservation Federation is the publication of the Conservation Federation of Missouri (ISSN 1082-8591). Conservation Federation (USPS 012868) is published bi-monthly in January, March, May, July, September and November for subscribers and members.

Of each member’s dues, $10 shall be for a year’s subscription to Conservation Federation Periodical postage paid in Jefferson City, MO and additional mailing offices.

Send address changes to:

Postmaster Conservation Federation of Missouri

728 West Main Jefferson City, MO 65101

FRONT COVER

This extremely rare sighting of a whooping crane was photographed on WRP property in north-central Missouri by Dale Humburg on November 21, 2021 using a Canon 5D camera and a Canon 100-200 mm lens

4 CONSERVATION FEDERATION

The

Food

13 21 31

Features Events

Swamp

Ripple Effect

for Thought - Millet 9

Highlights

Director's Message President's Message Life Members Affiliate Spotlight 3 8 11 14 Departments 32 6 18 22 24 28 32 35 38 42 44 46 49 52 55 60

Business Partners

Thank you to all of our Business Partners.

Platinum

Gold

Bushnell

Doolittle Trailer

Enbridge, Inc.

Silver

Custom Metal Products

Forrest Keeling Nursery

Learfield Communication, Inc.

Lilley’s Landing Resort & Marina

Bronze

Association of Missouri Electric Coop.

Black Widow Custom Bows, Inc.

Burgers’ Smokehouse

Central Electric Power Cooperative

Drury Hotels

Iron

Bass Pro Shops (Independence)

Bee Rock Outdoor Adventures

Blue Springs Park and Recreation

Brockmeier Financial Services

Brown Printing

Cap America

Central Bank

Community State Bank of Bowling Green

G3 Boats

MidwayUSA

Pure Air Natives

Redneck Blinds

Rusty Drewing Chevrolet

Roeslein Alternative Energy, LLC

Missouri Wildflowers Nursery

Mitico

Quaker Windows

Simmons Starline, Inc.

St. James Winery

Gray Manufacturing Company, Inc.

HMI Fireplace Shop

Hodgdon Powder Company, Inc.

Missouri Wine & Grape Board

NE Electric Power Cooperative, Inc.

NW Electric Power Cooperative, Inc.

Ozark Bait and Tackle

Williams-Keepers LLC

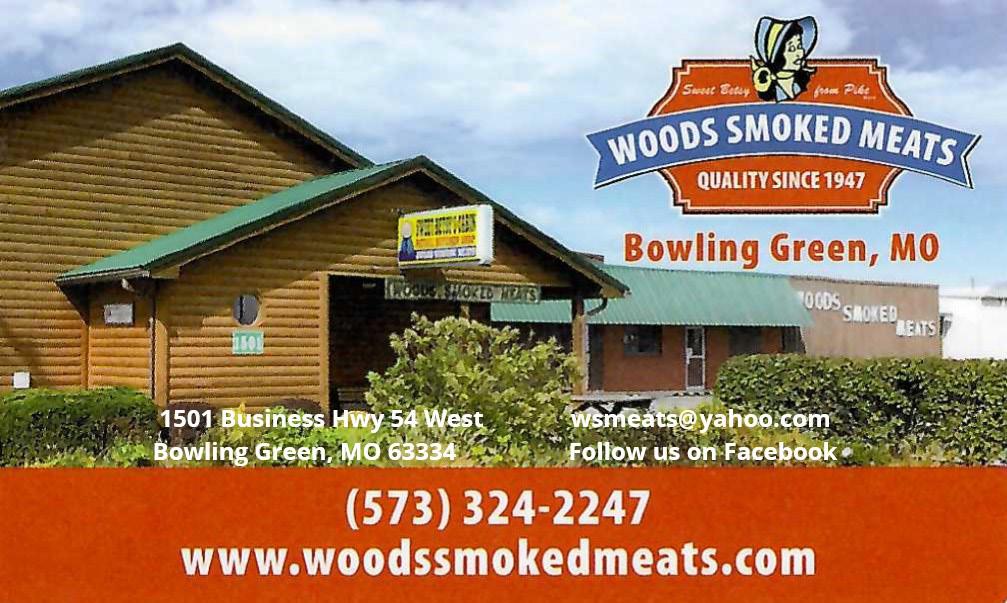

Woods Smoked Meats

Dickerson Park Zoo

Farmer’s Co-op Elevator Association

Gascosage Electric Cooperative

General Printing Service

GREDELL Engineering Resources, Inc.

Heartland Seed of Missouri LLC

Hulett Heating & Air Conditioning

Kansas City Parks and Recreation

Lewis County Rural Electric Coop.

Missouri Native Seed Association

Scobee Powerline Construction

Sprague Excavating

Tabor Plastics Company

Truman’s Bar & Grill

United Electric Cooperative, Inc.

Your business can benefit by supporting conservation. For all sponsorship opportunities, call (573) 634-2322.

SEPTEMBER - 2023 5

Wetlands Need People!

How can wetlands need people? Don’t people need wetlands? In the other articles in this issue, you will read about all of the benefits wetlands provide people ranging from cleaning water and reducing flood damages to providing places to connect with nature. But why would wetlands need people?

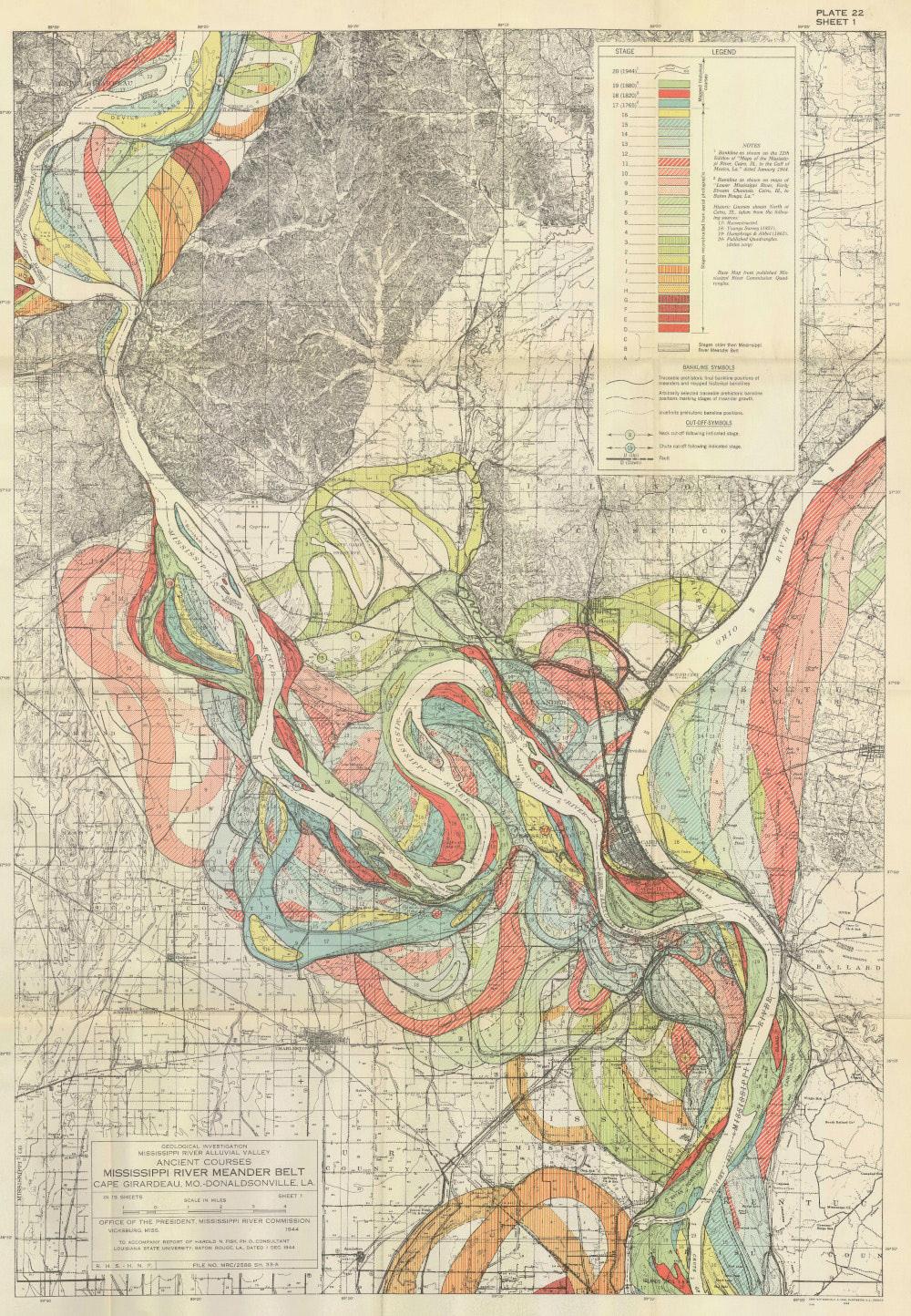

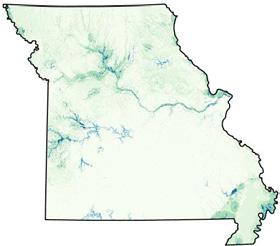

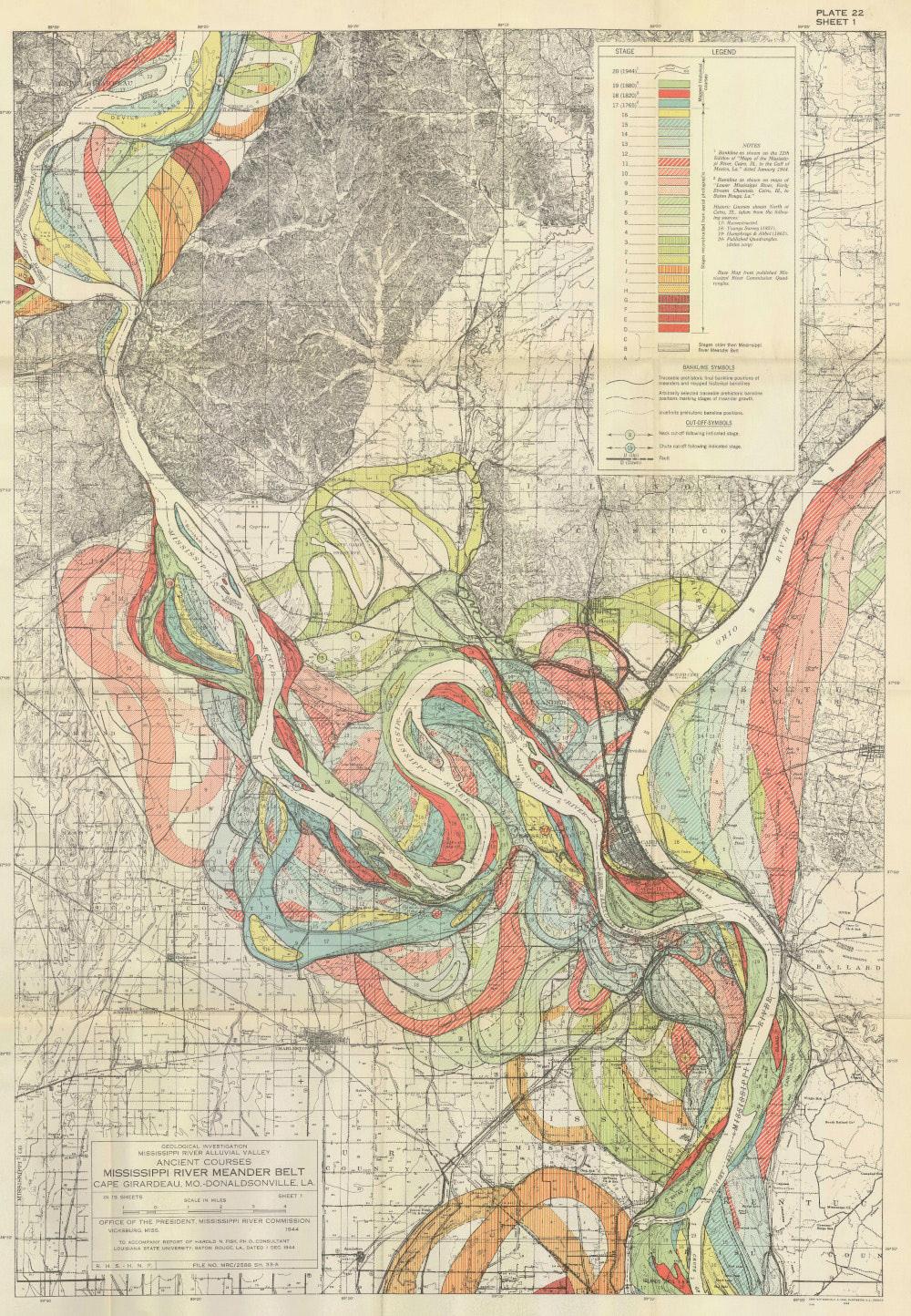

To answer this question, we first need to look at the processes that gave shape to Missouri’s wetlands. Most of them are connected to river systems. When we think of rivers, we often have an image of a river channel; however, a more accurate description of a river would extend from bluff to bluff, including the floodplain. In completely unaltered systems, both river channels and wetlands would be on the move, albeit in slow motion, shaped by the movement of water. Changing currents would carve out new paths for channels and abandon old ones that would then turn into wetlands. During flood pulses, water flowing across the floodplain would scour out depressions creating new wetlands and in places where the waters slowed, it would deposit sediment filling in some older wetlands. Thus, the locations of wetlands were also on the move. This movement is what created and sustained the diversity of Missouri’s riverine wetlands.

But today, river channels and wetlands are stuck in place, they can’t move! We have aggressively engineered river channels to eliminate the creation of new paths and the abandonment of old ones. In doing so, we have eliminated a key process that once created wetlands. We have constructed dams to regulate river flows and built extensive levee systems that disconnect river channels from floodplains.

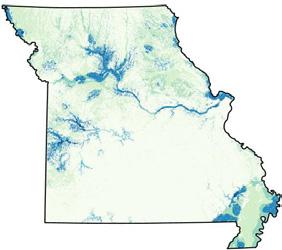

Together these two activities have essentially cut most wetlands off from their life support system, the natural flood pulses that created new wetland depressions, eliminated older ones, and provided all with water. At the same time, we have developed elaborate ditch and tile systems to quickly drain water off floodplains and higher ground back into river channels. All these activities combined have resulted in the loss of nearly 90% of our wetlands and most of those remaining are cutoff from the formative processes that created them, shaped their unique characteristics, and ultimately sustained them.

In the highly altered river systems (channels and floodplains) of Missouri today, the fate of wetlands is now in the hands of people. Human activities now determine the amount, distribution, and characteristics of wetlands more so than natural river processes. With this in mind, we need to focus on wetland protection, restoration, and management. Can we protect the small fraction of wetlands that remain on Missouri’s landscape? Can we restore additional wetlands and the stream flows that sustained them? Can we better manage them to emulate natural seasonal pulses of inundation and drying or at least provide critical resources needed to support a wide range of wetland-dependent species? It’s up to us to work together and reimagine how we can contribute to healthier river systems (channel and floodplains) through the restoration and management of ecological flows, channelfloodplain connections, and wetlands.

6 CONSERVATION FEDERATION Feature Story

One way people have always influenced the fate of wetlands is through public policy. By our actions or inactions, we ultimately contribute to the policies that either enhance or diminish wetland protections and increase or decrease public funding for wetland/river management and restoration. In the early 1970’s, people across the nation rallied for greater protection of our nation's waters and this led to the passage of the Clean Water Act. This law made it illegal to drain, fill, or pollute “waters of the United States” without a permit. Up until that time, wetland drainage was rampant. This single law provided protection to millions of acres of wetlands and dramatically reduced the rate of wetland loss. People, at that time, provided an incredible victory for wetlands.

In a single day this spring, the U.S. Supreme Court erased these protections for over half of the wetlands in the United States in the Sackett v. EPA ruling. In this case, they ruled that Waters of the United States included only those wetlands that adjoin clearly defined “Waters of the United States.” This ruling more narrowly defined “Waters of the United States” than previous definitions proposed by Republican and Democrat administrations. The Southern Environmental Law Center estimates this ruling will eliminate protections for at least 45 million acres of wetlands.

To put this number in perspective, it has taken partners in Missouri an incredible amount of work and significant funding to restore about 200,000 acres of wetlands over the past 30 years. Chris Wood, president and CEO of Trout Unlimited said, “The court has severely eroded a 50-year national commitment to clean water, and misses the obvious point that wetlands are often connected to streams through subsurface flows.” Jim Murphy of the National Wildlife Federation elaborated, "I don't think it’s an overstatement to say it’s catastrophic for the Clean Water Act.”

Now that the Supreme Court has made this ruling, it will require the U.S. Congress to amend the original Clean Water Act to restore wetland protections or for state or local jurisdictions to strengthen protections within their boundaries. Before I said wetlands need people and now hopefully you can see it’s urgent!

Our generation needs to act now to ensure we do not lose the wetland protections we inherited from our predecessors in 1972. During a Senate debate about the Clean Water Act in 1972, Republican Senator Howard Baker noted, “As I have talked with thousands of Tennesseans, I have found that the kind of natural environment we bequeath to our children and grandchildren is of paramount importance,” he said. “If we cannot swim in our lakes and rivers, if we cannot breathe the air God has given us, what other comforts can life offer us?” Will thousands of Missourians let our elected officials know how important wetlands are to them?

I started this article by saying wetlands need people. Let me rephrase, wetlands need you!

They need you to consider the position of candidates on wetlands the next time you vote. They need you to let your elected officials know how important wetlands are to the quality of life for Missouri citizens. They need you to be involved in conservation organizations to amplify your voice amongst others. They need you to become wetland ambassadors letting others know the critical role wetlands play in reducing flood damages, maintaining clean water, providing places to connect to nature, and so much more. A great way to start is by bringing a friend with you the next time you visit a wetland to duck hunt, fish, bird, photograph, or simply watch wildlife. Research shows that developing personal connections to wetlands leads to greater involvement in wetland conservation. Previous generations of Missouri citizens have left us with an incredible legacy of working together to improve the fate of Missouri wetlands. It’s now our time to build upon their successes and leave an even brighter future for the next generations.

Missouri

SEPTEMBER - 2023 7

Feature Story

Andrew Raedeke, Ph.D. Migratory Game Bird Coordinator

Department of Conservation

(Left) People with personal connections to wetlands are more likely to support wetland conservation.

(Photo: MDC)

(Right) A map created by Harold Fisk showing the movement of the Mississippi River Channel in Southeast Missouri. This movement helped shape floodplain wetlands.

President’s Message Why Wetlands Matter

Wetlands are so important to our everyday lives. They filter the water we drink, recharge the aquifers that irrigate our crops, and help protect against flooding. Wetlands support a diverse suite of wildlife, including waterfowl and other migratory birds. The economic impact of wetlands cannot be overstated. Birders and waterfowl hunters generate tens of billions of dollars in economic activity annually, on top of the many ecosystem services wetlands provide to society.

I’d argue that everyone benefits from wetlands, but especially those of us who enjoy outdoor recreation. The sad thing is, that wetlands in the U.S. are extremely imperiled. In Missouri alone, around 90% of historic wetlands have been lost. And sadly, that number is going to increase.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a ruling that will severely limit Clean Water Act protections for wetlands. The Court overturned decades of precedent regarding which wetlands will receive federal protections. Previously, a wetland with a “significant nexus” to a stream would be granted protection if the stream fell under the jurisdiction of the Clean Water Act. Now, two waters must have a “continuous surface water connection” and be “indistinguishable” for that protection to extend to an adjacent wetland. If you care about clean water, healthy fish and wildlife populations, or any of the myriad of services wetlands provide, this should concern you. Wetlands are an invaluable part of the ecosystem, even if they aren’t physically touching a stream. Wetlands recharge groundwater that feeds streams. They support wildlife that serve important functions in other, nonwetland habitats. To say that wetlands aren’t crucial to protected streams unless they are touching is poor policy and worse science.

So what does this ruling really mean? The legal and policy implications are still being analyzed, but we can expect that 50 to 60 percent of all wetlands in the U.S. will lose federal protection. Missouri’s long history of altering streams and floodplains to support agriculture, navigation, and development means that many of our wetland are behind levees, and therefore lack a surface connection to an adjacent stream. This means these wetlands can be filled, drained, paved, or otherwise destroyed without the requirement to replace that resource somewhere else. It means that our drinking water will be more expensive to treat. It means that flooding is going to get more severe.

And it means that many sensitive wetland species will face greater declines.

I hate to introduce the wetlands issue of our magazine on a negative note, but it’s hard to talk about wetlands without acknowledging the significance of this decision. Everyone who works in wetland conservation is facing a reality where our work just got a lot harder – but also more important than ever.

As you read through the wetlands issue, consider why wetlands are important. Think about how important it is to turn on your faucet and have affordable, clean water whenever you want it. Think about a time you went birding, or waterfowl hunting, and how important those memories are to you and your loved ones. Or consider the devastating impact flooding has had in Missouri, and those times we all wished we could do something more to help.

We can do something, and we will do whatever it takes. CFM will be right here, fighting to restore and protect our wetlands and preserve your right to recreate on them. Earlier this year, we hosted a wetlands summit, where conservationists from all over Missouri came together to plot the future trajectory of wetland science in our state and beyond. If you want to know what you can do, just stay tuned. Our members are passionate about wetland conservation, and you can be assured that when the time comes to take action, we will.

Don’t forget to get outside this fall; wetlands are a beautiful place to enjoy all Missouri has to offer. Maybe I’ll see you out there.

Zach Morris President, CFM

8 CONSERVATION FEDERATION

A wetland I helped design and build - using Clean Water Act mitigation funding, which is now in jeopardy, now supports multiple broods of ducks every spring and provides many ecosystem services. (Photo: Courtesy of Zach Morris)

missouri Native Grasslands

Save the Date

April 9-11, 2024

Capitol

Attendance will be limited. Early registration begins in December 2023.

Hosts/Contacts

As a result of a multi-agency and partner conversation in the summer of 2022, The Missouri Department of Conservation, Conservation Federation of Missouri, and Missouri Natural Resources Conservation Service are proud to present the 2024 Missouri Native Grasslands Summit. This all-inclusive event is designed for attendees to take a collective, deeper look into our state’s native grassland ecosystems, from remnant prairies to workings lands establishment and management, and collaborate with ideas and solutions to reverse the current trend in habitat loss. Recommendations from the Summit will be shared with the leadership of partner organizations that have an interest in Missouri’s native grasslands.

Who should attend: Anyone who has an interest in enhancing, protecting, and restoring Missouri’s prairie remnants and the expansion and management of native grass plantings.

Frank Loncarich Frank.Loncarich@mdc.mo.gov 417-451-4158

Visit confedmo.org/grasslands for more information.

Micaela Haymaker mhaymaker@confedmo.org 573-634-2322, ext. 101 Bill White William.White4@usda.gov 573-291-9224

2024

Summit

Plaza Hotel

City,

Jefferson

Missouri

Member News

Why I Became a Life Member of CFM: Laurie Wilson

Ever since I can recall, I have enjoyed the outdoors and being surrounded by nature. As a young girl, I remember playing in the woods, climbing trees, and wading in the creek with neighborhood friends. I was never concerned with getting muddy or little dirt under my nails. In adulthood, my zest for the outdoors increased, which fueled my desire for a lifetime membership with the Conservation Federation of Missouri (CFM)!

For almost two decades I had the privilege of working for CFM. Additionally, I had the pleasure of working with numerous individuals and organizations that shared my passion for the outdoors.

This is why I have continued to serve CFM in any capacity that I can. For nearly ninety years now, CFM has been known as “The Voice for Missouri’s Outdoors.” I believe in their mission to ensure the preservation of our great outdoor heritage, not only for you and me, and for our families, but most importantly, for future generations.

In Memory & Honor

I strongly encourage you to become a life member of CFM. Join us today to help promote and protect the natural resources of our great state!

Cheryl Tarbox

Marilyn Pohlman

Laura Richardson

Keith Hoffman

Barry Kirchhoff

Sheridan Polatis

Mr and Mrs Dennis Schrumpf

Mr and Mrs Stan Griffhorn

Dale Schrumpf

Richard Schrumpf

Barry Marquart

Mr and Mrs Jack Langley

Mary Ellen Gray & Aidan Rose Watson

Richard E Tucker

10 CONSERVATION FEDERATION

In Honor of Gary Van De Velde Paige Brockmeyer

In Honor of Lucas Wilson Mr and Ms Bill Kirgan

In Memory of Timothy Kirchhoff

LIFE MEMBERS OF CFM

Charles Abele

* R. Philip Acuff

* Duane Addleman

* Nancy Addleman

Tom Addleman

Nancy Addleman

* Michael Duane

Addleman

James Agnew

Carol Albenesius

Craig Alderman

* Allan Appell

Victor Arnold

Bernie Arnold

Richard Ash

Judy Kay Ash

Carolyn Auckley

J. Douglas Audiffred

Ken Babcock

Bernie Bahr

Michael Baker

* James Baker

Dane Balsman

Lynn Barnickol

Jamie Barton

Michael Bass

Robert Bass

Don Bedell

David F. Bender

Rodger Benson

Leonard Berkel

Barbi Berrong

Jim Blair

John Blankenbeker

Andy Blunt

Jeff Blystone

Kim Blystone

Glenn Boettcher

Arthur Booth

* Dale Linda Bourg

Stephen Bradford

Marilynn Bradford

Robin Brandenburg

Mark Brandly

Kathie Brennan

Robert Brinkmann

Robert Brundage

* Scott Brundage

Bill Bryan

Alan Buchanan

Connie Burkhardt

Dan Burkhardt

Brandon Butler

Randy Campbell

Brian Canaday

Dale Carpentier

* Glenn Chambers

Bryan Chilcutt

Ed Clausen

* Edward Clayton

* Ron Coleman

Denny Coleman

Rhonda Coleman

Liz Cook

Mark Corio

* Bill Crawford

Andy Dalton

DeeCee Darrow

Ryan Diener

Joe Dillard

Tim Donnelly

Cheryl Donnelly

Ron Douglas

Chuck Drury

* Charlie Drury

Tom Drury

Ethan Duke

Mike Dunning

William Eddleman

John Enderle

Theresa Enderle

Joe Engeln

Marlin Fiola

* Mary Louise Fisher

Howard Fisher

Andrew Fleming

Matt Fleming

Howard Fleming

Sara Fleming

Lori Fleming

Paula Fleming

* Charles Fleming

Bob Fry

Manley Fuller

David Galat

Gene Gardner

Matt Gaunt

Jason Gibbs

Timothy Gordon

Blake Gornick

David Graber

Tim Grace

Jody Graff

Richard & Sally Graham

Joseph Gray

Tyler Green

Jason Green

Gery Gremmelsbacher

Debbie Gremmelsbacher

Jason Gremmelsbacher

Bernie Grice Jr.

Mark & Kathy Haas

Tom & Margaret Hall

Christopher Hamon

* Deanna Hamon

J. Jeff Hancock

Herman Hanley

Keith Hannaman

Elizabeth Hannaman

John Harmon

* Milt Harper

Jack Harris

David Haubein

Jessica Hayes

* Susan Hazelwood

Mickey Heitmeyer

Loring Helfrich

* LeRoy Heman

* Randy Herzog

Bill Hilgeman

Jim Hill

Mike Holley

Rick Holton

CW Hook

* Allan Hoover

John Hoskins

Todd Houf

* Mike Huffman

Wilson Hughes

Larry Hummel

* Patricia Hurster

Kyna Iman

Jason Isabelle

Jim Jacobi

Aaron Jeffries

Robert Jernigan

Jerry Jerome

Roger & Debbie Johnson

* Don Johnson

* Malcolm Johnson

* Pat Jones

Steve Jones

John Karel

Thomas Karl

Jim Keeven

* Duane Kelly

Cosette Kelly

Junior Kerns

Todd Keske

Robert Kilo

* Martin King

Bill Kirgan

* Judd Kirkham

* Ed Kissinger

Sarah Knight

TJ Kohler

Jeff Kolb

Chris Kossmeyer

Chris Koster

Dan Kreher

Carl Kurz

* Ann Kutscher

Larry Lackamp

Kyle Lairmore

* Jay Law

* Gerald Lee

Debra Lee

Mark Lee

Randy Leible

* Joel LeMaster

* Norman Leppo

* John Lewis

Bill Lockwood

Leroy Logan

Christine Logan - Hollis

Bob Lorance

Ike Lovan

Wayne Lovelace

Kimberley Lovelace-

Hainsfurther

Jim Low

Mark Loyd

Emily Lute-Wilbers

Martin MacDonald

Michael Mansell

Steve Maritz

Danny Marshall

John Mauzey

Bill McCully

Chip McGeehan

Teresa McGeehan

Nathan "Shags" McLeod

Jon McRoberts

Richard Mendenhall

Tom Mendenhall

Donna Menown

Cynthia Metcalfe

Walter Metcalfe

Larry Meyer

Stephanie Michels

Mitchell Mills

Joshua Millspaugh

Davis Minton

Lowell Mohler

John Moore, Jr.

Johnny Morris

Zachary Morris

John Mort

Leanne Mosby

Steve Mowry

Diana Mulick

David Murphy

* Dean Murphy

Richard Mygatt

* Steve Nagle

Rehan Nana

J. Roger Nelson

Jeremiah (Jay) Nixon

Gary Novinger

Frank & Judy Oberle

Larry O'Reilly

Charlie & Mary O’Reilly

Beth O'Reilly

Anya O'Reilly

Jeff Owens

Austin Owens

Sara Parker Pauley

Scott Pauley

Randy Persons

Edward Petersheim

Albert Phillips

Jan Phillips

Glenn & Ilayana Pickett

Jessica Plaggenberg

Becky Plattner

Jerry Presley

Albert Price

Nick Prough

Kirk Rahm

Kurtis Reeg

John Rehagen

David & Janice Reynolds

Carey Riley

Kevin Riley

Mike Riley

Dana Ripper

John Risberg

Mary Risberg

Ann Ritter

Charles Rock

Derrick Roeslein

Rudy Roeslein

Charles Rogers

Kayla Rosen

Gerald Ross

Pete Rucker

Tyler Ruoff

Benjamin Runge

William Ruppert

Tom Russell

Jacob Sampsell

Bruce Sassmann

Jan Sassmann

Frederick Saylor

Michael Schallon

Mossie Schallon

* Evelyn Schallon

Thomas Schlafly

Pamela Schnebelen

Donald & Deb Schulte-

henrich

Tyler Schwartze

* Ronald Schwartzmeyer

Timothy Schwent

Travis W. Scott

George Seek

Arlene Segal

* E. Sy Seidler

* Sara Seidler

Anita Siegmund

Emily Sinnott

Douglas Smentkowski

Gary & Susanna Smith

Zachary Smith

* M.W. Sorenson

* Ed Stegner

Jeff Stegner

Everett Stokes

William Stork Jr.

Winifred Stribling

Norm Stucky

Mary Stuppy

* Mark Sullivan

Jacob Swafford

Jim Talbert

Norman Tanner

Travis Taylor Richard Thom

Don Thomas

Tim Thompson

* Jeff Tillman

Robert Tompson

Mike Torres

Matt Tucker

David Urich

Jennifer Urich

Alex Uskokovich

Gary Van De Velde

Barbara vanBenschoten

Lee Vogel

Albert Vogt

Frank Wagner

Ray Wagner

* Julius Wall

Ginny Wallace

Mervin Wallace

Randy Washburn

Mary Waters

Henry Waters, III.

Daniel Weinrich

Michael Weir

Robert Werges

Evelyn Werges Bennish

Tom Westhoff

Gary Wheeler

Georganne Wheeler Nixon

Mark Williams

Dennis Williams

Dr. Jane Williams

Stephen Wilson

Michael Wilson

Laurie Wilson

Jonathan Wingo

Jon R. Wingo

Michael Wiseman

Daniel Witter

Brenda Witter

* Addie Witter

Owen Witter

Dick Wood

Howard Wood

Joyce Wood

Nicole Wood

Charles M. Wormek

Brad Wright

Suzanne Wright

David Young

Judy Young

Dan Zekor

Daniel Zerr

Jim Zieger

Robert Ziehmer

Emily Ziehmer

Lauren Ziehmer

Colton Zirkle

Ethan Zuck

Guy Zuck

Mark Zurbrick

*Deceased

SEPTEMBER - 2023 11

Member News

Enter for your chance to win! Mega Mega Raffle Raffle Winner drawn Friday, December 1, 2023 Mega Raffle r I B S Enjoy a case (18 slabs) of Smoked Baby Back Ribs with a cooler. These will be individually wrapped and frozen. Est. Value $500 You do not need to be present to win. Questions: info@confedmo.org 573-634-2322 $10 per chance Visit online confedmo.org/store 3 ways to purchase tickets: Send check payable to: CFM, 728 W. Main St. Jefferson City, MO 65101 Scan QR T R I P 3 Night Stay at Big Cedar Lodge, Top of the Rock Adventure Passes for Two Guests, Dogwood Canyon Nature Park Passes for Two Guests, Round of Golf for Two Guests at Buffalo Ridge, Breakfast for Two Guests at Devil's Pool Restaurant, Lunch for Two Guests at Truman Café & Custard, Dinner for Two Guests at Devil's Pool Restaurant. 4 prizes!! $1000 Bass Pro gift card b a s s p r o $1,000 $500 Bass Pro gift card b a s s p r o $500 Est. Value $2300

MDC Celebrates the Year of the (Swamp) Rabbit with Research

Happy Year of the Rabbit! According to the Chinese Zodiac, the Year of the Rabbit comes around every 12 years, and the last one was in 2011. At that time, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and the World Lagomorph Society reminded us of the rabbit’s status as a keystone species in many ecosystems and that nearly one in four rabbits, hares and pikas are considered threatened. Unfortunately, the outlook has not improved since then. Some may be surprised to learn that, outside of ubiquitous species like the eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus) or the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), many rabbit species are habitat specialists, and those are the ones often at risk. To better understand and conserve our local wetland specialist, the swamp rabbit (Sylvilagus aquaticus), the Missouri Department of Conservation has been monitoring the entirety of their habitat in the state since 1993.

Recently, MDC conducted a more focused survey of swamp rabbit habitat in the River Bends Priority Geography, a region bordering the Mississippi River in the southeasternmost part of Missouri that holds considerable opportunity for wetland conservation. Extreme flooding events between 2011 and 2019 completely inundated much of this region and prompted concern that swamp rabbit populations were in trouble. Swamp rabbits generally seek high ground or wait out floods in tree canopies, but prolonged flooding would inevitably impact the hardiest of the bunch. So, in the winter of 2021, survey crews meandered through suitable patches searching for swamp rabbit latrines, which are often located on downed decaying wood or other elevated surfaces. Surprisingly, latrines were found more often in habitat patches on the unprotected side of the Mississippi levee, the Batture side.

The Batture land may appear to be an unforgiving environment where wildlife is entirely displaced when the river runs high and swift. But what makes for a shortterm loss may be a longer-term gain for wildlife. Flood risk prevents development, so the habitat patches in the Batture land are generally larger and closer together than the small, scattered ones on the protected side of the levee.

Since swamp rabbits are able swimmers, reaching new habitat patches across a small stretch of water may be easier than crossing an open expanse of row crops. At the patch scale, the pulse of nutrients, scouring, and silt deposition may promote understory plant growth. One study found an uptick in the body condition of whitetailed deer 1-2 years following a major flood. It may be that swamp rabbits recolonized the Batture land quickly and, given plentiful resources, did what rabbits do best. Thus, the survey may have caught the population at its greatest abundance following the major floods.

Though managers may be able to provide upland refugia or improve wetland habitat on the levee side of the River Bends, the mighty river and its floods will continue to shape habitat on the Batture side of the Mississippi, potentially to the benefit of swamp rabbits and other wildlife. Meanwhile, MDC’s monitoring of the swamp rabbit across its range in the state has continued through 2023, coincidentally promoting and advancing knowledge for this unique species in this celebratory year. Next year will be the year of the Dragon…flies.

Leah Berkman

SEPTEMBER - 2023 13 Member News

A swamp rabbit spotted during the 2023 survey of their entire range in Missouri. Seeing a swamp rabbit is rare so surveyors instead look for latrines on downed logs to confirm their presence in a habitat patch. (Photo: Kylie Bosch)

Missouri Ducks Unlimited

Established in 1937, Ducks Unlimited (DU) is the world’s largest nonprofit organization dedicated to conserving wetland habitat in North America. DU has protected nearly 120,000 acres for waterfowl in Missouri over the last 30 years, investing $22.4 million. DU is able to deliver this work by partnering with private individuals, landowners, state and federal agencies, scientific communities and other conservation organizations.

Wetlands improve the overall health of our environment by recharging and purifying groundwater, moderating floods, and reducing soil erosion. They are the most productive ecosystems, providing critical habitat to more than 900 wildlife species and invaluable recreation opportunities for people to enjoy.

“If you spend time outdoors in the state of Missouri, there’s a good chance that Ducks Unlimited has had a hand in creating or keeping that opportunity in place,” said DU state chairman, Renee Hahne. “We are waterfowl conservationists, but also know that our work is beneficial to a wide range of wildlife species. More wetlands on the landscape creates clean drinking water as well, keeping toxins out of our streams and rivers.”

Currently, DU is working on several project across the state. At Loess Bluff National Wildlife Refuge (Forest City), engineers have completed designs for a low 6,000-foot-long levee to improve water management between the Eagle Pool and Long Slough unit, the largest tract of wet prairie remaining in Missouri.

“There are a tremendous numbers of snow geese, trumpeter swans, king rails, and bald eagles that use Eagle Pool throughout the year,” said Casey Bergthold, Missouri Conservation Program Coordinator for DU. “Our work will create critical habitat these species need to thrive during the migration and breeding season.”

Farmers also play an important role for the future of wetland conservation in Missouri. In the Bootheel, Rice Specialists Dave Wissehr and Tony Jaco are administering a program funded by USA Rice, Walmart, and other partners.

It provides incentive payments to farmers for keeping their rice fields flooded longer into the winter and spring so that migrating waterfowl can feed and rest there. In 2022, 16 contracts were signed, impacting over 4,150 acres.

“My family has been farming in Missouri for generations, so I know first-hand the impact we as producers can have on the environment,” said Mark Flaspohler, DU’s Director of Agriculture Programs. “Every year we are seeing more farmers invest in sustainable agriculture, and we are doing our best to support those efforts.”

For more information on Missouri Ducks Unlimited visit www.ducks.org/missouri or find them on Facebook.

14 CONSERVATION

FEDERATION

Affiliate Highlights

(Top) Waterfowl utilizing a flooded, southeast Missouri field in January. The Rice Stewardship Program, a partnership between USA Rice, NRCS and Ducks Unlimited, promotes winter re-flooding on cropland acres to benefit migratory bird species. (Photo: Tony Jaco)

(Bottom) Tony Jaco, Missouri DU Consultant, visiting a private land wetland in southeast Missouri. The expansion of the DU Ag Program means more support for wetland management on working lands in Missouri. (Photo: Brad Pobst)

Affiliate Organizations

Anglers of Missouri

Association of Missouri

Electric Cooperatives

Bass Slammer Tackle

Burroughs Audubon

Society of Greater Kansas City

Capital City Fly Fishers

Chesterfield Citizens

Committee for the Environment

Columbia Audubon Society

Conservation Foundation of Missouri Charitable Trust

Deer Creek Sportsman Club

Duckhorn Outdoors Adventures

Festus-Crystal City Conservation Club

Forest and Woodland

Association of Missouri

Forest Releaf of Missouri

Friends of Rock Bridge Memorial State Park

Gateway Chapter Trout Unlimited

Greater Ozarks Audubon Society

Greenbelt Land Trust of Mid-Missouri

Greenway Network, Inc.

James River Basin Partnership

L-A-D Foundation

Lake of the Ozarks Watershed Alliance

Land Learning Foundation

Legends of Conservation

Little Blue River Watershed Coalition

Magnificent Missouri

Mid-Missouri Outdoor Dream

Mid-Missouri Trout Unlimited

Midwest Diving Council

Mississippi Valley Duck Hunters Association

Missouri Association of Meat Processors

Missouri Atlatl Association

Missouri B.A.S.S. Nation

Missouri Bird Conservation Initiative

Missouri Birding Society

Missouri Bow Hunters Association

Missouri Caves & Karst Conservancy

Missouri Chapter of the American Fisheries Society

Missouri Chapter of the Wildlife Society

Missouri Coalition for the Environment

Missouri Conservation Agents Association

Missouri Conservation Heritage Foundation

Missouri Conservation Pioneers

Missouri Consulting Foresters Association

Missouri Disabled Sportsmen

Missouri Ducks Unlimited- State Council

Missouri Environmental Education Association

Missouri Forest Products Association

Missouri Grouse Chapter of QUWF

Missouri Hunting Heritage Federation

Missouri Master NaturalistBoone's Lick Chapter

Missouri Master NaturalistGreat Rivers Chapter

Missouri Master NaturalistHi Lonesome Chapter

Missouri Master NaturalistMiramiguoa Chapter

Missouri Master NaturalistOsage Trails Chapter

Missouri Master NaturalistSpringfield Plateau Chapter

Missouri National Wild Turkey Federation

Missouri Native Seed Association

Missouri Outdoor Communicators

Missouri Park & Recreation Association

Missouri Parks Association

Missouri Prairie Foundation

Missouri River Bird Observatory

Missouri River Relief

Missouri Rock Island Trail, Inc.

Missouri Rural Water Association

Missouri Smallmouth Alliance

Missouri Society of American Foresters

Missouri Soil & Water Conservation

Society-Show-Me Chapter

Missouri Sport Shooting Association

Missouri State Campers Association

Missouri State Parks Foundation

Missouri Taxidermist Association

Missouri Trappers Association

Missouri Trout Fishermen's Association

MU Wildlife & Fisheries Science

Graduate Student Organization

Northside Conservation Federation

Open Space Council of the St. Louis Region

Outdoor Skills of America, Inc.

Ozark Chinquapin Foundation

Ozark Fly Fishers, Inc.

Ozark Land Trust

Ozark Riverways Foundation

Ozark Trail Association

Ozark Wilderness Waterways Club

Perry County Sportsman Club

Pomme De Terre Chapter Muskies

Quail & Upland Wildlife Federation, Inc.

Quail Forever & Pheasants Forever

River Bluffs Audubon Society

Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation

South Side Division CFM

Southwest Missouri Fly Fishers

St. Louis Audubon Society

Stream Teams United

Student Air Rifle Program

Tipton Farmers & Sportsman's Club

Tri-Lakes Fly Fishers

Troutbusters of Missouri

United Bow Hunters of Missouri

Watershed Conservation Corps

Wild Bird Rehabilitation

Wild Souls Wildlife Rescue Rehabilitation

Wonders of Wildlife

World Bird Sanctuary

Young Outdoorsmen United

SEPTEMBER - 2023 15 Affiliate Highlights

Contact your local Shelter agent to insure your auto, home, life, farming, hunting & fishing gear. Find an agent near you at ShelterInsurance.com. Shelter Insurance® is a proud sponsor of Share the Harvest & the Conservation Federation. SEASON It’s Your

Committed to Community & Conservation

Owned by the members they serve, Missouri’s electric cooperatives do more than provide reliable and affordable electricity. They are active in their communities, concerned for the wellbeing of their neighbors and devoted to the rural way of life that makes the Show-Me State a special place to live, work and play. Missouri’s electric cooperatives are dedicated to protecting the land, air and water resources important to you and your quality of life. Learn more at www.amec.coop.

Partnerships – A Necessity for Aquatic Systems Conservation

Missourians place great value on the state’s fish, forests, and wildlife. Citizen-led efforts incorporated those values into the state constitution in the 1930s and placed responsibility for protecting and managing these natural resources in the hands of the Missouri Conservation Commission. However, the missions of other state and federal agencies, along with non-government organizations, impact these resources, making it vital that partnerships (either formal or informal) be developed to address common interests or potential conflicts. Because water is a part of every phase of human life, these partnerships are particularly important to ensure the protection and conservation of wetlands and other aquatic systems.

Since more than ninety percent of Missouri is privately owned, it is crucial that private landowners be involved in partnerships designed to enhance wetlands conservation in the state.

A review of the history of the conservation movement in Missouri reveals that private wetlands owners were at the forefront of many of these efforts. The significance of privately owned wetlands is more critical now than ever before, and will only increase in the future. Therefore, they must have a seat at the table as future plans for aquatic systems conservation are crafted.

Wetlands and associated aquatic systems are important to every citizen or visitor to the state. The importance of water quantity and quality is obvious, but recreation, including hunting, fishing, wildlife viewing, nature study, and just having places to “get away” are all important contributors to the quality of life in Missouri. These elements must be included in all partnerships guiding wetlands and aquatic conservation as we move forward.

18 CONSERVATION FEDERATION Feature Story

Agriculture is the state’s number-one industry and wetlands and other aquatic systems are impacted by these operations in many regions of the state. Mutual understanding and respect, along with a willingness to compromise, must be incorporated into partnerships between agriculture and conservation interests.

Following is a list of agencies/organizations, summaries of their respective missions, and brief discussions of how wetlands and associated fish, forests, and wildlife resources might be impacted. The list is by no means complete, but it demonstrates the importance of partnerships that incorporate the values Missouri citizens place on wetlands and aquatic resources. The list also illustrates the diversity of priorities and the need for cooperation among all stakeholders.

Missouri Department of Natural Resources (DNR): A key focus of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources is to ensure the health and quality of life for the more than 6 million people living in Missouri, based upon the recognition that this goal is closely tied to the health and quality of the state’s air, land, and water resources. The agency’s very existence depends on enriching Missouri’s natural resources and the state's environmental and economic vitality. With its system of parks and historic sites, this agency contributes directly to wetlands and aquatic system conservation and associated outdoor recreation. In addition, through its Clean Water Commission. Soil and Water Programs and other programmatic areas, DNR establishes networks vital to partnerships among agencies and landowners.

U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS): The mission of the USFWS is to work with others to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, plants, and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people. Much of the work of this agency involves wetlands and other aquatic systems. Through international treaties and federal law, this agency is also responsible for migratory bird conservation and overseeing provisions of the Endangered Species Act. Many species of migratory birds are wetlands dependent and because of wetlands losses across the nation, including Missouri, a high percentage of plant and animal species on the threatened and endangered list are associated with wetlands.

The USFWS manages a series of nine national wildlife refuges in Missouri, which combined, protect and conserve thousands of acres of wetlands and associated habitats for many plants and animals.

Two of these refuges are managed specifically for endangered species. These refuges also provide recreational opportunities covering a wide range of interests.

The USFWS delivers the Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program in Missouri, providing technical and financial assistance to private landowners interested in improving habitats for wildlife. This program includes a substantial focus on wetlands and is coordinated with similar efforts of other agencies and organizations; an excellent example of such coordination involves ways that Partners staff work with staff delivering MDC’s Landowner Assistance Program to ensure optimal outcomes for fish, wildlife, and private landowners.

U. S. Geological Survey (USGS): The mission of USGS is to provide a science foundation to help America achieve sustainable management and conservation of biological resources in wild and urban spaces, and places in between. The Missouri Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit located at the University of Missouri in Columbia (MU) carries out the mission of USGS in our state. The Unit has existed since 1937 when the newly formed Missouri Conservation Commission, as one of its first acts, approved a partnership with the federal government and MU to establish this research arm. It was a recognition by the Commission that conservation decisions should be science-based following the results of research carried out by qualified scientists. That guidance continues today and no aspect of conservation has benefitted more than wetlands and other aquatic systems.

Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS): The mission of NRCS is to deliver voluntary conservation solutions that allow agricultural communities to feed a growing nation blessed with clean and abundant water, healthy soils, and resilient landscapes while protecting and enhancing these natural resources. NRCS serves as the interface between production agriculture and natural resource conservation among landowners who raise crops or livestock for a living.

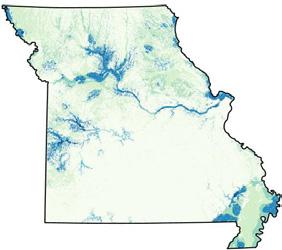

In addition to assisting on “working lands”, NRCS holds easements on 66,700 acres (88% are permanent) under the Wetland Reserve Program (WRP) in Missouri. These easements cover marginal farmlands that were historically wetlands. NRCS provides funding for restoring wetlands and assistance is provided for longterm management.

SEPTEMBER - 2023 19 Feature Story

WRP is a prime example of how privately owned lands become part of the formula for successful wetlands and other aquatic systems conservation and management efforts in Missouri.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE): The mission of the Civil Works Division of the USACE is to develop and manage the nation’s water resources; support commercial navigation; restore, protect, and manage aquatic systems and manage flood risks, all in an environmentally sustainable, economic, and sound manner. The USACE plays a key role in the protection, restoration, and management of wetlands and other aquatic systems. Because of the breadth of its mission, its efforts can present challenges in the natural resources conservation arena.

One area of direct impact regarding USACE’s involvement in wetlands conservation is the agency's role in enforcing regulations of Section 404 of The Clean Water Act which prohibits dredging or depositing fill in wetlands without the required permits and/or mitigation. These activities generally are related to either development or agriculture.

Ducks Unlimited, Inc. (DU): The mission of DU is to conserve, restore and manage wetlands and associated habitats for North America’s waterfowl. These habitats also benefit other wildlife and people. United States membership totals 700,000, with 19,000 of those members in Missouri. Since its beginning in 1937, DU has conserved approximately 15 million acres in Canada, the United States, and Mexico. DU has partnered with conservation agencies in Missouri to acquire, restore and manage several thousand acres of wetlands in the state. In addition, DU has secured perpetual conservation easements on approximately 10,000 acres of wetlands and associated habitats in the state.

DU also places a high priority on public policies that benefit wetlands conservation nationally and in individual states, including Missouri. The organization is highly respected among policymakers across the nation.

Conservation Federation of Missouri (CFM): The CFM began in 1935 when conservationists throughout Missouri came together with the mission of eliminating political involvement from fish, forest, and wildlife conservation decisions.

Their efforts led to amending the state’s constitution in 1936, creating the Missouri Conservation Commission and ultimately the Department of Conservation.

CFM has more than 100 affiliates and is a forum to consolidate views from a broad spectrum of conservation interests. For more than 88 years, CFM has worked to ensure the integrity of the state’s conservation on every front, including wetlands. They are a very effective voice of the citizenry when it comes to natural resource issues.

Conservation successes in Missouri over the past nearly nine decades have been well chronicled. The value Missouri citizens place on the state’s natural resources and their willingness to provide finances to cover the costs of protecting and managing them, including those dependent on wetlands and aquatic systems, are the primary keys to these successes. In addition, leadership provided by Conservation Commissioners, MDC directors, and the heads of other state and federal agencies and conservation organizations have been key components.

The “secret sauce” making all of this work has been the willingness of all with a stake in or responsibility for wetlands and aquatic systems conservation to understand and respect their differing priorities and be willing to work together to craft solutions accepted by all. Many outside the state have referred to this approach as the “Missouri Model” of conservation, particularly as it applies to wetlands. The partnerships developed over the years must be continued and strengthened to ensure future successes in these vital arenas.

Sara Parker Pauley & Ken Babcock

20 CONSERVATION

FEDERATION Feature Story

Photos: Courtesy of MDC

The Ripple Effect of the Wetland Summit

In February, the 2023 Missouri Wetland Summit was co-hosted by the Conservation Federation of Missouri (CFM) and the Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC). Despite tempting Old Man Winter, the road conditions in Missouri were serviceable and icy circumstances only impacted the attendance of a few planning to travel from out of state. Overall, 330 people from 15 states attended this first-time event to listen and discuss the history, merits, and trajectories of wetland conservation in the Show-Me state.

Coming off the tail of the global pandemic, it was enjoyable to see people face-to-face, catch up with old friends, and make new acquaintances. The planning committee prepared for the event by sending out a survey prior to the gathering to see what was on participants’ minds and help presenters frame the discussions. During the Summit, a full slate of presentations took attendees on a journey of where Missouri wetland conservation has been, what have been the bright points in our collaborative history, and what challenges and opportunities are headed our way. No doubt, it was an ambitious endeavor and in no way were we going to be able to cover all topics of interest in great detail. However, this was never actually the goal. The Missouri Wetland Summit was to re-engage, share ideas, and serve as a new starting point for the future.

We asked for input, suggestions, and questions during and after the Summit. We wanted to know what people thought and why they cared about wetland conservation. Again, the passion and commitment were palpable as over 170 people provided their thoughts and ideas. Thank you. Your voices were heard. Some great points were offered as to what are fundamental aspects of a successful wetland program, what areas we need to do a better job in coordinating, how can we attempt to increase agency capacity, as well as how we grow public support and action for wetland conservation. As I have worked on the summary report and had various followup discussions, I am beginning to see ripple effects.

Ideas expressed at one time or another during this threeday event are radiating outward. For example, people are discussing the potential to organize strike teams for invasive species.

Others are calling up neighboring agencies and asking what their needs might be in the coming year so they can help each other out. I’ve had the pleasure to brainstorm and consider what a “Birding Classic” in Missouri might look like in the future. MDC staff and partners have also revisited our tiered approach to Conservation Opportunity Areas and identified potential locations in southeast Missouri that currently fall in the “white space” and should be incorporated as locations eligible and worth conserving within the future. I know that many more ideas and discussions are swirling around the eddies and sub-surface currents that will continue to mature and begin to make waves in the days, months, and years to come. I look forward to seeing how far they radiate.

I’ll admit that I’ve already gone back, rummaged through some of the presentation slides found on CFM’s website, confedmo.org/wetlands/ and pulled several useful nuggets out for handy talking points. I hope you too benefited from the presentations and interaction with others provided at this event. We merely scraped the surface and know a wide range of topics, issues, and opportunities for wetland conservation must be addressed in greater depth as we move forward. The best way to do that is together, across disciplines, listening to each other’s perspectives to find common ground and tangible solutions. I invite you to reach out to me and connect to find ways to build off our past and tread into new waters to pursue different opportunities. Wetlands are variable and so are the solutions. We need to keep the ripple effect going, and I look forward to wading in to advance these efforts and making waves for wetland conservation in Missouri.

Frank Nelson Wetland Systems Manager, MDC

SEPTEMBER - 2023 21

Member News

A King Rail. (Photo: Courtesy of MDCi)

National Partnerships Help Guide a Small Shorebird’s Road to Recovery

The majority of 51 regularly occurring shorebird species in North America use wetlands habitats which are vital to their survival. But shorebird populations are decreasing at alarming rates, down 33% over the last 40 years, and 16 species have declined over 50%. The 2022 State of the Birds Report (https://www.stateofthebirds.org/2022/) made clear that it is critical that conservation action be taken to reverse long-term downward trends for 269 bird species including several shorebirds. One bird, the Lesser Yellowlegs, is at the forefront, requiring action due to a 70% loss in abundance.

This is the story of a recent national partnership called the Road to Recovery Initiative (https://r2rbirds.org/), that was formed as a result of the 2019 three billion birds lost paper published in Science. To begin, four species ambassadors were chosen as pilot species to move forward.

Lesser Yellowlegs was chosen due to precipitous declines and a group of dedicated researchers who had identified threats and mapped migratory routes. This species will be a model engaging social and ecological scientists, educators, habitat delivery professionals, conservationists, communications specialists, industry, private landowners and public land managers to work together to build a strategy that will help lead the way for this wetland bird and many other similar species at the tipping point. Species that, without a conservation strategy, may not recover.

Of many national conservation partnerships, Road to Recovery is innovative because it brings together a broad community of biological and social scientists to meet conservation challenges head on. This approach requires efficiency and problem-solving throughout the migratory pathways of birds, addressing knowledge gaps, building relationships and finding resources to address issues for the health of the land, its people and wildlife.

22 CONSERVATION FEDERATION Feature Story

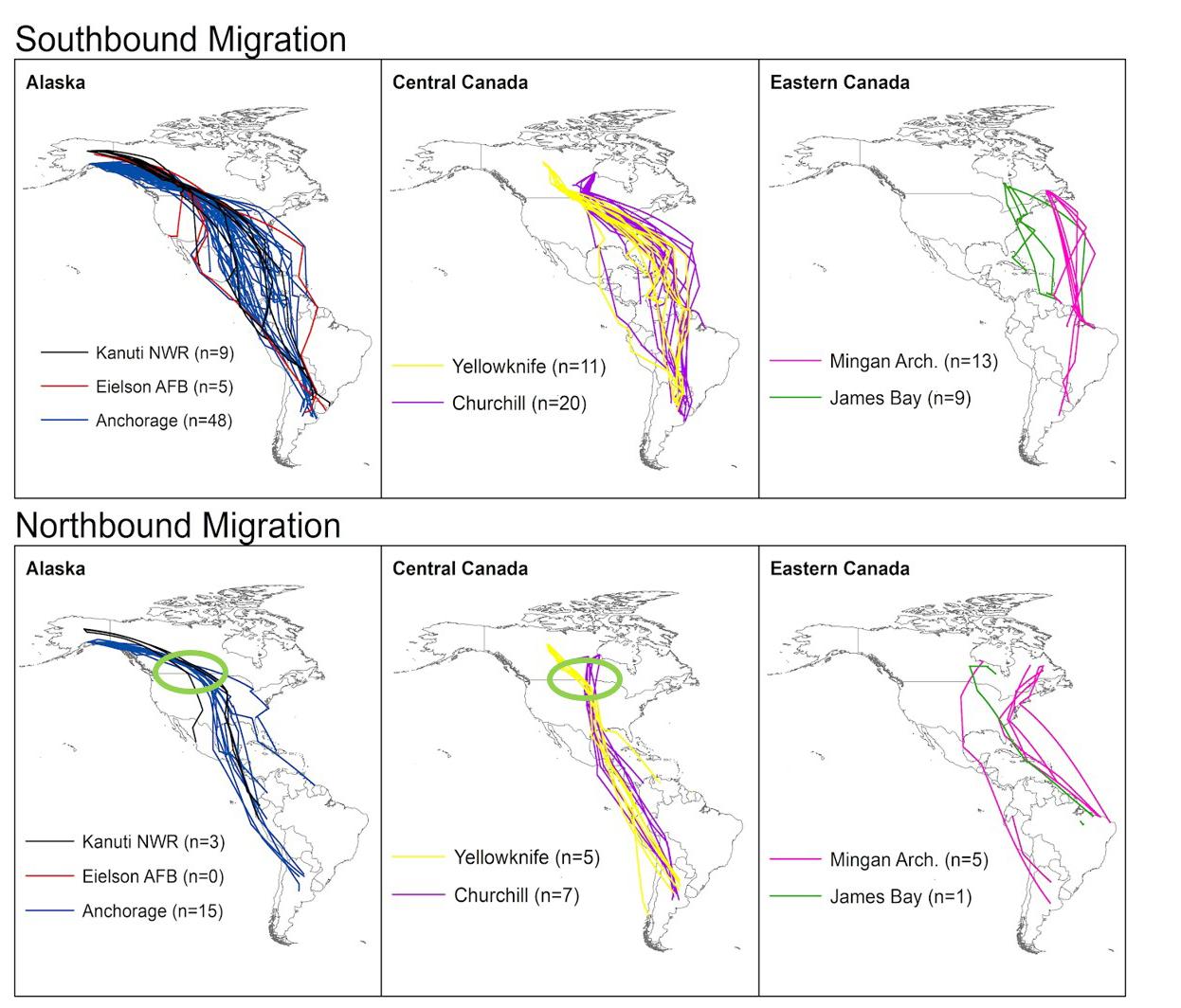

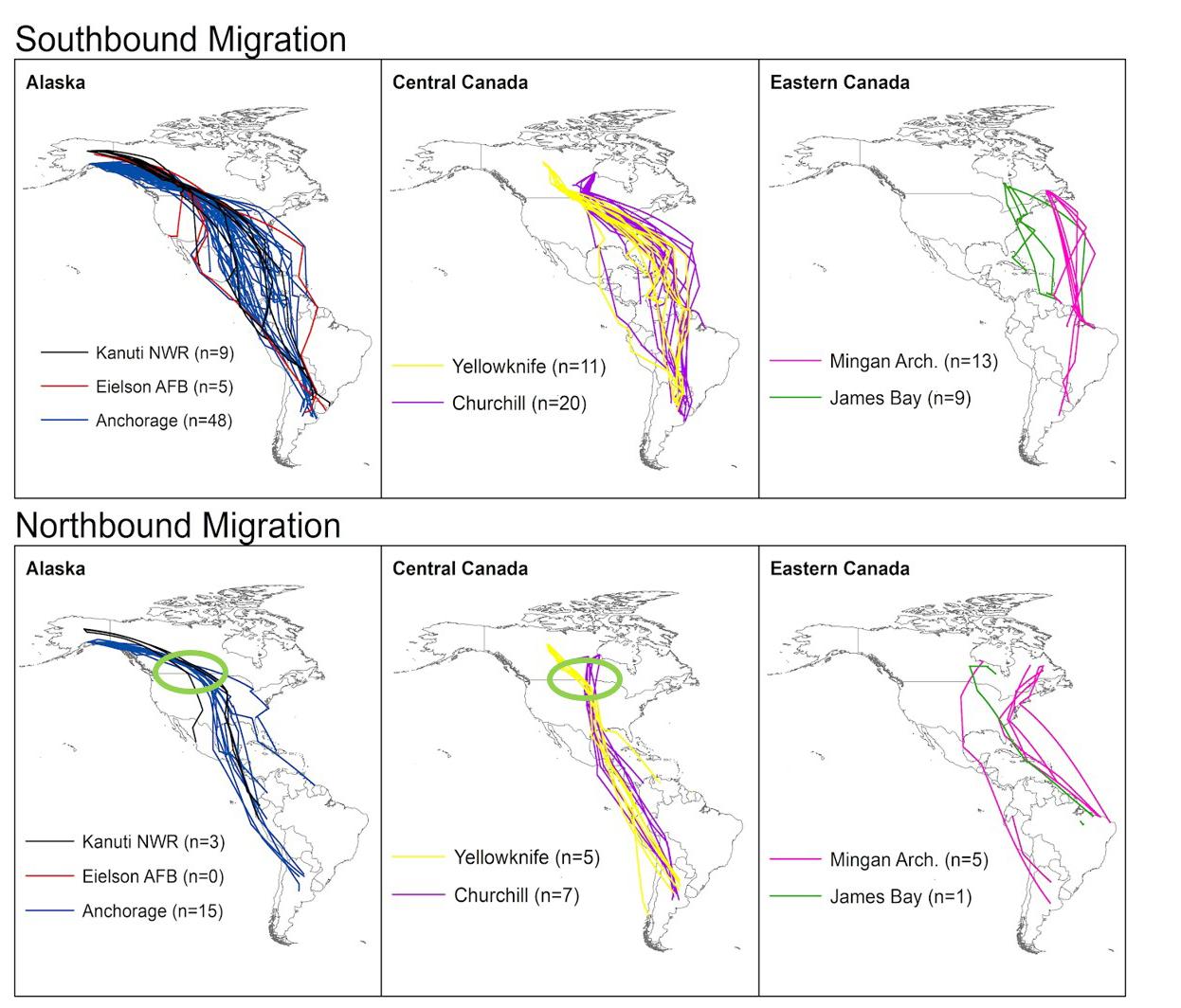

The Lesser Yellowlegs is helping frame this kind of collaboration first and foremost with scientific research to help define strategies. Biologists’ knowledge of life history together with learning their movements (where they winter, how they migrate and where they breed) (Fig. 1) and the threats they face throughout the migratory pathway will pave the way to help them. These are small 8-inch-high shorebirds, which weigh no more than a tangerine, and fly 20,000 miles annually round-trip. They occur throughout the western hemisphere, nesting in Canada and Alaska and wintering in South America. There are three major threats facing the species: 1) loss of shallow wetland habitats with exposed mudflats, 2) lack of wetland management across the migratory pathway during critical life stages, and 3) nonsustainable hunting in the Caribbean and South America. Extreme weather events and a variety of other threats may also impact this species. So, addressing these primary threats, among others, requires consideration of biological, and ecological needs balanced within social, cultural and economic spectrums throughout the hemisphere, a long road to be sure.

Along the road to recovery for Lesser Yellowlegs, partnership building is just beginning and a Lesser Yellowlegs Working group is starting to pinpoint where priority regions and habitats are so they can strategically determine where effective conservation partnership development should be to maximize success. Engaging all stakeholders is critical. Strong communication and listening will help guide solutions and having conservation dollars through state, federal, local and private sources to help public and private land managers with habitat work and management will be necessary as will voluntary collaboration with landowners.

Missouri happens to be on the road to recovery for this shorebird and the Bootheel, as part of the lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley (MAV), is an important priority region during migration. In spring, the birds funnel up through the MAV, stopping along the way to consume freshwater wetland invertebrates in very shallow wetland habitats. Freshwater invertebrates are critical to body condition and health and also aid in successful nesting. So, in response to the threats to survival the continuing restoration, enhancement and protection of shallow wetland habitat as well as improving wetland management at appropriate times of year statewide, including fall migration are important strategies to help these birds and similar species rest and refuel on their migratory journey. Just as Missouri is important for migrating waterfowl, for the same reasons, restoring, enhancing and managing quality shallow wetland habitat is critical for ensuring these shorebirds arrive on the breeding grounds in prime body condition to lay eggs and raise young and have the resources they need to arrive on the wintering grounds.

The national Road to Recovery Initiative is working closely with federal agencies, like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Natural Resources Conservation Service, the North American Bird Conservation Initiative, 50 state agencies (including the Missouri Department of Conservation), multiple universities, non-government organizations and international agencies and organizations to bring awareness about the major declines of birds and developing tools to implement recovery actions.

As is evident from the 1930s formation of the Conservation Federation and Conservation Commission, Missouri is one of the best to take part in national partnerships like this and has become a leader working internationally too. The work is just beginning because the 269 species mentioned earlier will need similar focus and strategic partnering as much as the Lesser Yellowlegs. Just as important, however, the partnership needs people, including Missourians, to champion and make a difference for wetland conservation, not only for birds and other wetland dependent species but for the health of people who depend on the land for clean, plentiful water.

Kelly Srigley Werner

SEPTEMBER - 2023 23

Feature Story

(Left) A banded Lesser Yellowlegs bird in its preferred shallow wetland habitat with sparse low growing vegetation. Bird height 8 inches, vegetation ~4 inches. (Photo: Carrie Olson)

(Top) Lesser Yellowlegs tracking: migration pathways and connectivity. Birds track through Missouri mostly on the Alaska and Central Canada routes. The Prairie Pothole region (circled) is a 'rest stop' for north and south migration. (Citation: McDuffie, L.A., etal. 2022. Flyway-scale GPS tracking reveals migratory routes and key stopover and non-breeding locations of Lesser Yellowlegs. Ecology and Evolution 12: e9495.)

Our Beloved Brazen Beavers

Many Missourians do not have a fondness or respect for “brazen beavers” and their behaviors. The bad reputation of beavers stems from their tireless efforts to chew down trees, dam streams, and burrow into streambanks. Often these activities cause unwanted issues like road and field flooding, culvert plugging, burrowing, or tree damage.

Nevertheless, those same unwanted activities can enhance headwater streams, streamside wetlands, and their local aquifers, thereby benefiting the overall floral and faunal diversity. The changes beavers make on the landscape can also buffer natural disasters. During drought, beaver complexes provide wildfire resilience, refuge, and water storage. This localized availability of water can benefit farmers and animals alike in certain areas by keeping the water table high, grasses green and extending the growing season. On the flip side, beavers and their battery of woody stream bumps help slow down and spread-out fast-moving water during floods.

This rodent’s knack for extending the water cycle and interaction of plants within aquatic and terrestrial environments also helps cycle nutrients on an annual basis and store carbon long-term. If everyone recognized that beavers could be a low-cost or free means to restore ecosystem health, perhaps they would become known as “beloved beavers.”

It is hard to imagine how different our streamside landscapes must have looked before European settlement in North America when beaver population estimations were 60-400 million beavers! Many streams were hardly recognizable compared to how they look today. Instead of single-threaded channels, which often have tall, eroded, and barren streambanks, beaver-laden streams were transformed by transitory dams that created multithreaded channels, deep wetland and stream pools and interconnected floodplains. These systems were messy, complex, and diverse in all the right ways, allowing for massive amounts of habitat and species diversity and very high-functioning ecosystems.

24 CONSERVATION FEDERATION Feature Story

In the 1500’s through 1800’s, beaver pelts were highly sought after across the globe for making warm, waterrepellant, attractive hats. The fur trade was already devastating beaver populations in North America by the 1600’s. Beaver would likely have become extinct were it not for the discovery of silk, which was easy to mass produce, cheaper, and had similar desirable qualities to beaver fur. As beavers were disappearing from the landscape and waterways, their former habitats held some of the deepest and finest soils known, with accounts of some yielding four tons of hay per acre. Early settlers benefited from this topsoil but likely did not understand the role of beavers in creating and maintaining soil fertility.

Without beaver to rebuild and maintain stream and wetland dams, the complex beaver-controlled stream systems began to unravel and become simplified, looking more like streams we see today that are typically single channeled, incised, eroded, and lacking connection with the adjacent floodplain and/or wetlands. Adding insult to injury, colonization and land clearing caused increased watershed run-off, which eroded stream channels to straighter, larger, and even more simplified channels. Many were also channelized for navigation and farming, which further degraded the formerly very complex, messy, and diverse stream systems. This legacy of cascading changes has resulted in an ecological amnesia of the contributions that beavers once made to Missouri.

So where does that leave us? We can’t completely ignore that beavers cause problems for human structures and activities, but we also can’t ignore the degraded stream conditions we now face. In certain locations, beavers could offer low or no-cost solutions to some of our stream problems and be a welcome part of the system again.

Recent experiments in the Western US have been successful in encouraging beavers to re-colonize headwater streams. Studies have shown that beaver activity creates deeper pools in streams, adds sinuosity and complexity, stabilizes streambanks, elevates water tables, and reconnects floodplains and wetland systems to the stream. These studies have also revealed that beaver activity contributes to denitrification and flood attenuation, among many other things.

In areas without readily available beavers, beaver activity can be encouraged or even mimicked by creating Beaver Dam Analogues (BDA’s) and/or Post Assisted Log Structures (PALS). These structures are human-built beaver dams and log jams used in places where beaver may be lacking to create the habitats that beaver would have otherwise created. Utah State University has a plethora of research and step-by-step guides on what these structures do, where to locate them, and how to build them. The Missouri Department of Conservation has a research project starting this year on MDC and The Nature Conservancy land to test these structures and their effects.

Encouraging beaver activity may seem like risky business, but restoration work on the West and East coasts have come up with remarkable solutions that emphasize coexistence between man and beast. Beaver Deceivers, for example, are flow devices that keep beavers and their dams in place while allowing water to move through. They can be used around road culverts and water control structures as pond leveling devices to keep water levels below a certain elevation. There are also techniques to fence off and prevent unwanted tree damage.

In times where it seems like everyone is being asked to “do more with less”, perhaps we could re-adjust our attitudes and consider the benefits of beaver’s work and their engineering solutions that are free of charge! There is a balancing act between brazen unwanted activity and the benefits to streams and wetlands that beavers provide and finding where their activities are acceptable amid public interests. Acknowledging the history of beavers in Missouri and overcoming our ecological amnesia might allow us to lean into new opportunities for conservation success.

For more resources feel free to check out:

• https://www.fws.gov/media/beaver-restorationguidebook

• https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/TheBeaver-Restoration-Guidebook-v2.02_0.pdf

Ange Corson

SEPTEMBER - 2023 25

Left - Unhealthy and disconnected headwater stream system. (Photo: Jerry Wiechman)

Feature Story

Right - Functioning and connected headwater stream system. (Photo: Jerry Wiechman)

GOOD FOR LAND. GOOD FOR LIFE.

Prairie Prophets is a new media platform created by Roeslein Alternative Energy. We will be showcasing the stories and objectives of the recently awarded USDA Climate Smart Commidities grant through the Prairie Prophets podcast, video series, and website.

Everything prophits from prairie. Soil, air, water - and all kinds of life! Learn how you can make the most of your land with prairie restoration, cover cropping, and prairie strips. Visit prairieprophets.com.

26 CONSERVATION FEDERATION

SEPTEMBER - 2023 27

Learning to “Think Like a Wetland”

The Evolution of Wetland Restoration and Management in Missouri.

Acentral theme of the 2023 Missouri Wetland Summit was that wetland conservation and management in Missouri has, and is continuing to, evolve and move toward more complete “holistic” ecosystem-based approaches. The history of this evolution from 1.) “buyand-protect” acquisition of core lands in the 1940s and 50s based on authorizing purposes mainly for migratory waterfowl to 2.) current protection and restoration mainly from easements on private lands, and 3.) enhancement and restoration of both old and new wetland areas and sites using hydrogeomorphic understanding and principles is fascinating and truly represents inclusive ecologically based management and strategic purpose.

As Ken Babcock stated in his Summit remarks, this remarkable evolution in wetland conservation in Missouri has been possible because of the amazing focus, science, and leadership of those conservation “giants” that came before us and that we stand on the shoulders of. One such “giant” has been Dr. Leigh Fredrickson, who received a Lifetime Achievement Award from CFM at the Wetland Summit (see sidebar below).

28 CONSERVATION FEDERATION

Feature Story

We in Missouri are blessed to have had those prior “giants” and now the future cadre of new conservation leaders from the “Missouri Mafia” lineage.

I am sure that many of the Summit attendees could not help but think about their own conservation “lineage” and how they came to be seated at the meeting. I was no exception.

Like many who have chosen a career in natural resource conservation, I wanted to be a wildlife biologist because I liked, and loved to hunt animals, especially bobwhite quail and ducks. Being a farm kid from rural North Missouri, I naturally related animals and their needs to the land, but honestly, my primary interest was the animal. My entry to formal education in the conservation field began at Moberly Area Junior College, where I took basic college classes and met Wilbur Gunier, professor of zoology and botany. Wilbur loved bats, and after me pestering him enough, he took me on his many forays to band bats, where I then met his batbanding buddy Dr. William Elder, Professor at the University of Missouri-Columbia (MU). Then, in a natural sequence, “Doc” Elder became my undergraduate advisor when I continued my education at MU following Junior College.

I guess I did good enough in class that Doc hired me as a Teaching Assistant for his ornithology class – and he and wife Glennis took me, Bill Eddleman (his M.S. student working on Swainson’s warblers), and Rick Schwartz (a student friend that was a mammal “nut”) on numerous trips to crawl around in Missouri caves and band more bats. What a rag-tag crew, but we loved and were entertained by Doc’s many eccentric stories of research literally around the world. Elder’s first wife, Nina, was the daughter of Aldo Leopold, and Doc often repeated a question his ex-fatherin-law asked him. Aldo would ask: “Bill do you love caves because they have bats, or do you love bats because they live in caves?” With my twist, this simple question has stayed with me for life: "do I love wetlands because they have ducks, or do I love ducks because they live in wetlands?”

Because of my interest in ducks, Elder encouraged me to take a Waterfowl Ecology class at MU taught by Dr. Leigh Fredrickson, who was also the Director of the Gaylord Memorial Laboratory located at Duck Creek CA in southeast Missouri. The connections continued - Leigh had been a Ph.D. student under Milt Weller, who was Elder’s first Ph.D. student.

Leigh’s waterfowl class was a life-changing event for me –and began a life and career journey working on waterfowl and wetlands. Leigh taught his students that understanding waterfowl first required an understanding of the place they lived and were evolutionarily adapted to – wetlands across the globe. After Mizzou, my education took me to Oklahoma State University, where I studied waterfowl and wetlands across Oklahoma for a Master’s Degree– and, then subsequently a return to MU to work on a Ph.D. with Leigh on wintering mallards and bottomland hardwood wetlands. In both research ventures, my theses were as much about the wetland ecology the ducks used as they were about the ducks themselves.

In a wonderful “never know where I will be guided next” career path, I was blessed to work on waterfowl and wetlands at the University of California-Davis, California Waterfowl Association, and Ducks Unlimited. At DU, I became the head of conservation programs across North America – and, Leigh’s admonishment to learn how wetlands worked crossed my desk, and guided our work daily. In the next serendipitous twist of my life, I returned to MU in 1998 to work at the Gaylord Lab as Leigh retired. Leigh loved field trips to look at wetlands, and one day, Phil Covington, our old friend that was a previous MDC wetland manager at Ted Shanks CA and that then was with DU in Arkansas, called and said, “You all have got to come to Arkansas to see what this kid is doing with wetland restoration.

So, Leigh and I headed south to Possum Grape, AR, where we met Phil, Tom Foti – an ecologist with the Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission – and the kid “Jody Pagan.” Tom had helped train Jody, and together with Chuck Klimas of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in Vicksburg, they were advancing a new way of understanding, restoring and managing wetlands – something called a “Hydrogeomorphic Method” or “HGM” for short.

SEPTEMBER - 2023 29

Left - Sunrise Retrieve. (Photo: Dale Humburg)

Feature Story

Right - Aerial shot of Ted Shanks. (Photo: MDC)

Feature Story