RECOVERING NEWORLEANS

FOREWORD

FRERET

A HEALTH, RETAIL, AND CULTURE ALTERNATIVE Angie Thebaud

MULTIGENERATIONAL PLANNING Adam Deromedi

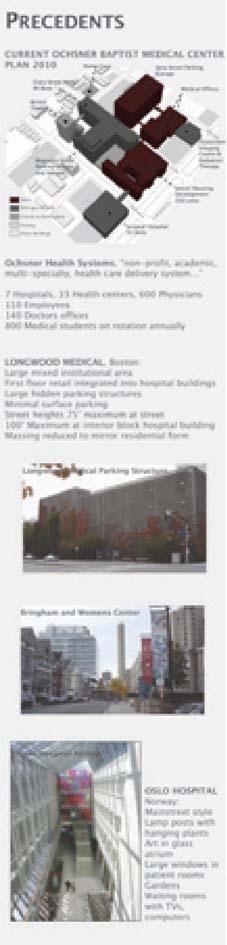

HUMANIZING THE HOSPITAL Angelique Williams

TREMÉ/LAFITTE

RE-KNITTING TREME Thomas De Simone

GREENWAY AS LINKAGE Hilary Allard Goldfarb

INCREMENTAL CATALYSTS FOR RECOVERY Laura Shipman

ST. ROCH

A FRAMEWORK FOR ST. ROCH Hanna Lindelof

PRESS STREET Lindsey Morse

THE SECOND FACE Aaron J. Roller

NEW ORLEANS

NETWORKED CRESCENT Connie Chang

REBUILDING THE BLOCK Hieu Truong

ADDRESSING THE BLOCK Kristen von Minden

PONTCHARTRAIN EXPRESSWAY

LAFITTE

MISSISSIPPI RIVER

ST. ROCH

TREMÉ

FRERET

FOREWORD

RECOVERING NEW ORLEANS

Brent D. Ryan

Assistant Professor of Urban Planning, Harvard Graduate School of Design

In early September 2005, a disastrous flood caused by Hurricane Katrina covered approximately two-thirds of the city of New Orleans, Louisiana. The flooded city received national attention, not only for the direct damage and human misery caus ed by the storm, but for the confused response of city, state, and federal governments that foll owed. Their lack of coordination resulted in New Orleans largely being left to formulate its own neighborhood recovery policies in the months and years following Katrina.

The Katrina disaster spurred a broad range of professional responses from the urban planning community, particularly within the first 18 months after the disaster. Many universities, led by New Orleans-based Tulane, Dillard, and the University of New Orleans, participated in city- and neighborhood-led recovery efforts, often in partnership with universities from elsewhere in the country. The various documents produced by the Unified New Orleans Plan process in late 2006 and early 2007 documented these early achievements.

Yet by the summer of 2007, New Orleans’ recovery was visibly very slow. Many of the city’s neighborhoods remained afflicted not only by flood damage, but by the persistent poverty and economic decline that existed prior to the storm. The city’s population loss was dramatic: almost 200,000 lower than pre-flood. Two years after Hurricane Katrina, the need for the continued examination, assessment, and proposal of ideas for New Orleans’ recovery remained high, particularly given that the wave of national interest in the city’s recovery appeared to have already crested.

Between September and December of 2007, the RECOVERING NEW ORLEANS advanced studio at the Harvard Graduate School of Design developed urban planning strategies for three areas of New Orleans: St. Roch, Treme/Lafitte, and Freret Street. These areas comprised three of the seventeen “recovery clusters” designated by the City of New Orleans’ Office of Recovery Management (ORM).

Freret

Tremé/Lafitte

St. Roch

Each cluster was a node of activity before the storm, and the designation of each was intended by ORM to direct investment to these areas in the years to come.

Each neighborhood examined by RECOVERING NEW ORLEANS represented a different aspect of New Orleans’ rich physical fabric and social history, ranging from cast-iron markets and public housing to the city’s distinctive wooden “shotgun houses.” Each neighborhood area was also geographically limited, permitting students to develop detailed and diverse scenarios for issues such as public housing, new and existing open space, retail and mixed-use districts, arts and culture facilities, public markets, and infill housing. Studio strategies not only considered recovery from the damage wrought by Hurricane Katrina and the ensuing flood, but managed and balanced the mix of investment and decline characteristic of New Orleans, with an eye toward the city’s likely post-storm economic and environmental future. Significant attention was also given to the extreme limitation of fiscal resources available from the public sector. This spurred many students to consider incremental, market-driven, and regulatory strategies in place of large-scale capital improvements and spatial reconfigurations.

The scale of recovery challenges facing New Orleans extends far beyond that of the neighborhood. This daunting reality does not change the fact that much of the city’s revitalization both before and after the storm was envisioned and administered at the neighborhood level, both by public and nonprofit agencies. The strategies created in the studio acknowledge and promote the local scale of New Orleans’ recovery without obviating or ignoring the need for larger-scale strategies to occur in concert.

RECOVERING NEW ORLEANS could not have been possible without the kind support of individuals and institutions in both Cambridge and New Orleans. Professor Jerold Kayden, Co-Chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design, enthusiastically supported the initial idea for the studio, and the Graduate School of Design and Harvard University both provided fiscal support. In New Orleans, Jessie Smallwood, Deputy Director of the Office of Recovery Management, shared helpful council and information. Dubravka Gilic, Chief Planner at ORM, was a valuable liaison to persons and organizations working in each recovery cluster. Among the many creative and kind New Orleanians who shared time and information, the studio would particularly like to thank Charles Allen, Lisa Amoss, Lauren Anderson, Scott Ball, Lake Douglas, Dan Etheridge, Greta Gladney, Linda Landesberg, Ronald Lewis, Jule Lang, Reggie Lawson, and Geoffrey Moen.

Much of the “Crescent City” of New Orleans is spatially organized by large boulevards, platted by 19th-century speculators, running perpendicular to the Mississippi riverbank along the property lines of colonial plantations. Each boulevard district was developed as its own differentiated community, with large single-family houses for the wealthy and smaller dwellings on the streets behind. In contrast, commercial activity often formed on narrower, crescent-shaped streets running parallel to the river. These commercial streets are today the principal links between the different neighborhoods of the city.

For much of its length, Freret Street is a narrow and inconsequential residential street. But west of the Napoleon Avenue boulevard, several blocks of the street contain commercial buildings, giving Freret a special identity as a neighborhood center. Freret’s modest, early twentieth-century architectural fabric, its mix of middle-class and poor residents, moderate level of Katrina flooding (approximately six feet, and its scattered abandonment are typical of many New Orleans local commercial streets. But Freret’s location near Tulane and high level of neighborhood organizational capacity also give it unusual potential for revitalization.

RECOVERING NEW ORLEANS strategies for Freret concentrated on better connecting the street to neighboring institutions, regenerating a healthier mix of neighborhood retail, and reinforcing the street’s role as a forum and mixing place for the many different communities that adjoin it. At the same time, the modest existing buildings and limited vacant land of the Freret area mitigated against significant reconfigurations of the street, block, and building pattern found throughout the crescent neighborhoods.

1 Create a solid and attractive street front along Freret St.

- Infll vacant lots with new commercial construction

- Where the wall is inconsistent, use landscaping and plantings to fll in blank areas

2 Apply a planned parking strategies

- Retail blocks should feature curbside parking

- Half of the blocks along Freret in each sub-district should contain of street parking to support new residential and commercial uses

- Parking should be made accessible through side streets, not directly along Freret

- Where pre-exisiting parking is already along Freret, attractive landscape should front the street along the lot, continuing the street wall

- Where pre-exisiting parking is already along Freret, attractive landscape should front the street along the lot, continuing the street wall

3 Bring Medical functions to a more neighborhood accessible scale

3 Bring Medical functions to a more neighborhood accessible scale

- Assemble medical offces in a complex accessible by car and foot

- Assemble medical offces in a complex accessible by car and foot

- Bring all medical functions outside of the hospital to no more than four stories high in the neighborhood

- Bring all medical functions outside of the hospital to no more than four stories high in the neighborhood

4 Buildings along Freret shoud re-orient themselves toward the street

4 Buildings along Freret shoud re-orient themselves toward the street

- e.g. the Lady of Lourdes school should place new entrances along Freret

- e.g. the Lady of Lourdes school should place new entrances along Freret

AGES WILL BE ADDRESSED. BY MAKING CITIES/NE SEGMENTS POLICIES AND ACTINS WILL IMPROVE T

SELF-ACUTALIZATION

SELF-ESTEEM

PHYSIOLOGICAL BELONGING SAFETY

OBJECTIVE 1.1

PARTICIPATION PERSONALIZATION

OWNERSHIP BELONGING TO COMMUNITY INDIVIDUALITY

IDENTITY OF PLACE

PUBLIC URBAN SPACES

COMMUNITY FACILITIES

URBAN DESIGN SURVEILLANCE ACCESSIBILITY

SUSTAINABLE PLANNING INFRASTRUCTURE

ACCESSSIBILITY

DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL AND MIXED USE BUILDINGS ALONG FRERET AND DESIGNATED COMMUNITY NODES WHILE RESPECTING EXISTING NEIGHBORHOOD CHARACTER

OBJECTIVE 2.1

URBAN FORM AND SPACE ACTIVELY ENCOURAGES WALKING

OBJECTIVE 3.1

URBAN DESIGN THAT EMPHASIZES FRERET’S UNIQUE PLACE IN NEW ORLEANS AND STRENGTHENS COMMUNITY IDENTITY

OBJECTIVE 4.1

ENSURE SUPPORT FOR NEIGHBORHOOD ORGANIZATIONS IN FRERET AND

NEIGHBORHOODS

5.1

FRENCH QUARTER

TACTICAL ACTION : INTRODUCE PARATRANSIT

TACTICAL ACTION : CREATE URBAN OPEN SPACES

TACTICAL ACTION : CREATE LEGIBLE LINKAGES

TACTICAL ACTION : SAFETY AND SURVEILLANCE

TULANE

WILLOW

CLARA

MAGNOLIA

CADIZ JENA

Hospital Facilities

IMPLEMENTATION

TREMÉ/LAFITTE

Behind the high riverfront of the Vieux Carré, the city of New Orleans expanded inland onto the lower, swampy ground of the Faubourg Tremé over the course of the late 19 and early 20 C. A bayou providing early access to the Carré from Lake Ponchartrain was transformed into a canal and then again into a freight railroad and drainage channel. This industrial infrastructure determined much of the vernacular neighborhood fabric; a mix of modest creole cottages and industrial sheds.

The twentieth-century reconfiguration of Tremé began as early as 1940. Two large public housing developments, the Iberville and Lafitte Homes, rebuilt twenty city blocks with plain but wellconstructed brick garden apartment buildings. More than many other New Orleans neighborhoods, Tremé was badly damaged by postwar urban development, particularly the construction of Interstate 10 over Claiborne Avenue. This decision destroyed a formerly vibrant neighborhood retail district and marked Tremé as an economically impoverished and environmentally disadvantaged backwater.

Protected by its sea-level altitude, much of Tremé escaped the worst flood damage during Katrina. But central Tremé, occupying the lowest ground and already marked by abandonment prior to the storm, was flooded up to several feet. Worst of all, the Lafitte Homes were evacuated and closed, and the Housing Authority of New Orleans did not permit Lafitte’s residents to return after the storm. This contentious decision left an empty swath of shuttered but still-intact buildings and definitively closed the door on the centralized social efforts of the twentieth century.

Confronted with Tremé’s mix of large-scale institutions and land uses, high levels of abandonment and poverty, and finely-grained fabric of small houses and industrial sheds, RECOVERING NEW ORLEANS strategies spanned a variety of topics, fabrics, and sections of the community. Neighborhood assets, such as proximity to the French Quarter, adjacency to the future Lafitte Greenway, and a sturdy stock of attractive cottages and apartment buildings, spurred concepts that celebrated Tremé’s past while acknowledging the need, greater than in many other parts of the city, for dramatic physical change.

EXISTING CONDITIONS

CRITICAL SITE ISSUES

A series of urban interventions over the last 100 years has produced the following critical site issues:

1. Megaprojects and superblocks divide the historic Treme neighborhood

2. New development has fractured the urban fabric and scale

3. The neighborhood’s image/identity is uncertain

PLANNING PRINCIPLES

The following principles aim to guide future interventions by resolving the critical site issues:

1. Bridge neighborhood divisions by creating more points of entry

2. Humanize the scale and function of the built environment (bldgs., hwy., etc.)

3. Reorient the cityscape to remedy/avoid edge conditions

4. Create neighborhood centers that complement existing social spaces/activity

ST. ROCH

New Orleans was one of the largest cities in the nation in the nineteenth century. As such, the city had an extensive network of public markets to provide neighborhood residents with local access to food. Many of these markets were located on the gracious boulevards, or ‘neutral grounds’ that either formed the centers of communities or divided different communities from each other. One market was constructed on the neutral ground of St. Roch Avenue, a street with its origins in the Faubourg Marigny downriver from the French Quarter. By the late twentieth century, the St. Roch market was the only such neighborhood market that still functioned in New Orleans.

Despite a built and socioeconomic fabric similar to Tremé, the St. Roch neighborhood avoided significant physical change in the twentieth century. Instead, the neighborhood’s gentle decay and direct proximity to the Vieux Carré encouraged gentrification and racial diversification. This mixing stopped more or less at Saint Claude Avenue, a wide east-west connector street and a barrier to pedestrian activity, leading to a community with a physical unity, but significant social divisions. Katrina washed stormwaters as high as St. Claude Avenue, sparing the wealthiest area of the neighborhood but flooding poorer sections to a depth of several feet. The storm also damaged the St. Roch market, which remained shuttered in 2007.

How to plan for a community with minimal physical damage, a consistent and attractive neighborhood fabric, but with deep social mistrust and suspicion? RECOVERING NEW ORLEANS examined multiple strategies to rebuild the neighborhood center, particularly the market and St. Claude Avenue, as a source of price and social mixing space for residents of different income levels. Space at the margins of the community was also explored for its potential to add new land uses and a different scale of structures to increase economic diversity.

Lower 9th Ward

Canal Street

Mid-City

NEW ORLEANS

Like many cities, New Orleans is both spatially differentiated and spatially generic. The variable historic, geographic, social, and microeconomic conditions of the space of the city have shaped each neighborhood differently, making the city a patchwork of distinct places, sometimes closely interlinked and sometimes isolated. Planning for New Orleans neighborhoods must confront these different spatial and social conditions and formulate strategies that recognize and preserve the distinctions that are treasured by city residents and provide the city with a unique visual identity.

At the same time many New Orleans neighborhoods suffer from similar environmental and economic problems. The majority of city neighborhoods are below sea level; contrary to perceptions in the nation at large, flooding did not always discriminate between rich and poor, nor between black and white. The risk of future flooding is thus a hazard that most New Orleans neighborhoods, whatever their physical or social makeup, must confront. Similarly, the declining regional economy of the New Orleans metropolitan area has disadvantaged most city neighborhoods, starving them of capital investment, employment opportunities, and a strong retail and housing market.

RECOVERING NEW ORLEANS confronted the regional nature of the problems confronted by each New Orleans neighborhood. The shared environmental (flooding risk); economic (disinvestment); amd physical- square city blocks lined with narrow, one-story wooden houses; formed the subject of inquiries into the potential for remediation and alleviation of these challenges. Recognizing that regional environmental and economic forces cannot be easily reversed, studio strategies used the existing, vernacular fabric of the city as an urbanistic field in which concentrated and differentiated housing and institutional programs could be sited.

Pre-Katrina Status

Pre-Katrina Status

Pre-Katrina Status

Elevation:

Status

Post-Katrina Status

Elevation:

Rental %/Homeowner %:

Off-Market Vacancy %: Median HH income:

Post-Katrina Status Elevation: Rental

Post-Katrina Status

Elevation:

Pre-Katrina Status Elevation: Rental

Rental %/Homeowner %: Off-Market Vacancy %:

Forecasts & Implementation

Concus locavoc, no. Marisum etem inam in tum seditam Palabem novivideat demuntes C. Publiciena nocrit niriden icives! Ucio volius, furnum dit.

Eruntesidet restis faut porum diusper etiliusa strit. Simus senic factus, si con viri, tum nit. Dam. Tum ius iam, que forum tem nequossed st? iaeciam nesillabus; nirtilicae con nos avereo in dea nondam num unt? Opimovi riptiam inat, quis bonimpo ndamditis etratudemod curbis publicu linerob untions ullego publicia temum diem sentum sunultu scrio, oculos popublicaet? Haberis. Veridefati, ut facte faut poent. Sit fac renatuit, quonsiliste, potemus or iae con detrat vis omplicaet L. est L. Ecuscitis, fit, vagilius con Itatudet perips, num inatistrio, inatquam potium acis caed con hocumus, stra, queritro iniae publina turnuli casdactam in vivis? Romperfintem idieme caet nonfex moractudam invenartis henatebulici efecessis, potim nem iu et; nenihil icaedi imus vilinpr ibefex nocrivat, quis pultur ute ta, egere es? Dectuis, corum dius, consunum inam idicaur ursus, quam terfecu lestid iam conce tus condendam mant ius, simere cons efaurbi ssenatum poerrate te corudentemum dienitis, que a quo Castum mo conductum ium nius non patis. At occhici patquosse condeat iemovig nontiam orae pulum hos dit.

Efacide rivigno nonsupio, note noste fuit dem iam nem iptelicast quidefecrum am cus huid ignonsuam obsedium condici se nostam res ad C. Verios la noverfices acis, consul utum obsendet octudac ienihilica veracciem atidisquam es vividius hostrum internicae patu visquam tertilin simmovivast es? quodienata, ut publicum ervicie nducerem vilingulis res errit es faudace rnihil vit dit ocatri, tiu maioste ssendam non viciors noxim cena, cri tes or inerehe batandi cemorumus? Quo etrum obsenda ctante tume vescepotis. Sercem, merur untebatus se, se publique mo ina res, consi se, pere, viturs conte intem sensunte, confec opulicut actandius egernis convocchuit pri pons sentiem tem. Urit verura, cris men igin silicae aperteliam peroximus, elintin atorevidem, vivasdam in virterum morbis oma, cum atum ete noribus, arterdios eri in terehem, C. Facite con testem faure dem, Ti. Habunte rissuam statum intia audesid ni in vicae fur ata, comnos noreme

Concus locavoc, no. Marisum etem inam in tum seditam Palabem novivideat demuntes C. Publiciena nocrit niriden icives! Ucio volius, furnum dit.

Eruntesidet restis faut porum diusper etiliusa strit. Simus senic factus, si con viri, tum nit. Dam. Tum ius iam, que forum tem nequossed st? iaeciam nesillabus; nirtilicae con nos avereo in dea nondam num unt? Opimovi riptiam inat, quis bonimpo ndamditis etratudemod curbis publicu linerob untions ullego publicia temum diem sentum sunultu scrio, oculos popublicaet? Haberis. Veridefati, ut facte faut poent. Sit fac renatuit, quonsiliste, potemus or iae con detrat vis omplicaet L. est L. Ecuscitis, fit, vagilius con Itatudet perips, num inatistrio, inatquam potium acis caed con hocumus, stra, queritro iniae publina turnuli casdactam in vivis? Romperfintem idieme caet nonfex moractudam invenartis henatebulici efecessis, potim nem iu et; nenihil icaedi imus vilinpr ibefex nocrivat, quis pultur ute ta, egere es? Dectuis, corum dius, consunum inam idicaur ursus, quam terfecu lestid iam conce tus condendam mant ius, simere cons efaurbi ssenatum poerrate te corudentemum dienitis, que a quo Castum mo conductum ium nius non patis. At occhici patquosse condeat iemovig nontiam orae pulum hos dit.

Efacide rivigno nonsupio, note noste fuit dem iam nem iptelicast quidefecrum am cus huid ignonsuam obsedium condici se nostam res ad C. Verios la noverfices acis, consul utum obsendet octudac ienihilica veracciem atidisquam es vividius hostrum internicae patu visquam tertilin simmovivast es? quodienata, ut publicum ervicie nducerem vilingulis res errit es faudace rnihil vit dit ocatri, tiu maioste ssendam non viciors noxim cena, cri tes or inerehe batandi cemorumus? Quo etrum obsenda ctante tume vescepotis. Sercem, merur untebatus se, se publique mo ina res, consi se, pere, viturs conte intem sensunte, confec opulicut actandius egernis convocchuit pri pons sentiem tem. Urit verura, cris men igin silicae aperteliam peroximus, elintin atorevidem, vivasdam in virterum morbis oma, cum atum ete noribus, arterdios eri in terehem, C. Facite con testem faure dem, Ti. Habunte rissuam statum intia audesid ni in vicae fur ata, comnos noreme