PLC things

PLC things all

First Thing

Answering the How

Hector Garcia

SOLUTION TREE:

CEO

Jeffrey C. Jones

PRESIDENT

8 12

Edmund M. Ackerman

SOLUTION TREE PRESS: PRESIDENT & PUBLISHER

Douglas M. Rife

18

ART DIRECTOR

Rian Anderson

PAGE DESIGNERS

Laura Cox, Abigail Bowen, Kelsey Hergül, Fabiana Cochran, Julie Csizmadia, Rian Anderson

Overthe years, compounding evidence has proven the power of implementing the Professional Learning Community at Work process. There are now hundreds of schools, in virtually every state and around the world, that have transformed their culture and improved student performance using the PLC process. (Please visit the AllThingsPLC locator at www.allthingsplc.info/plc-locator/us to learn more about specific schools near you.) Yet it is painfully evident that many school districts have struggled to implement the PLC principles for various reasons. While it is impossible to address all of the challenging factors, sometimes it just comes down to answering the “how.” While this topic has been covered in many ways, looking through a practitioner’s lens might help uncover new insight or generate new ideas. In Learning by Doing (DuFour, DuFour, Eaker, & Many, 2010), the authors contend that there are ve essential areas that district leaders need to address in order to e ectively implement PLC principles.

1. Clarify priorities.

2. Set speci c conditions.

3. Align leadership behaviors with the articulated purpose and priorities.

4. Establish indicators of progress to be monitored carefully.

AllThingsPLC (ISSN 2476-2571 [print], 2476-258X [Online]) is published four times a year by Solution Tree Press.

555 North Morton Street

Bloomington, IN 47404

800.733.6786 (toll free) / 812.336.7700

FAX: 812.336.7790

email: info@SolutionTree.com

SolutionTree.com

POSTMASTER

Send address changes to Solution Tree, 555 North Morton Street, Bloomington, IN, 47404

Copyright © 2023 by Solution Tree Press

5. Build the capacity of people throughout the organization to succeed in what they are being called on to do.

Since the term professional learning community has become ubiquitous in American schools, it is easy for educators to de ne it in various ways. Multiple de nitions and interpretations o er a unique challenge for school administrators and sta at every level. A district administrator who struggles to clearly articulate the key principles of a PLC at Work and the artifacts that need to be produced will inevitably create widespread confusion or low-level compliance.

One of the critical ways to solidify and clarify the priorities is to establish a road map

for the district that outlines the work. is can take the form of a one-page document that outlines what is meant by establishing collaborative teams, the four critical questions, and the essential components that will ensure everyone is pursuing a common goal. e road map outlines the speci c conditions that must be created in each school and the key artifacts associated with each component. is helps center conversations when monitoring progress with district and building administrators throughout the year.

is alignment of purpose within recurring opportunities for discussion ensures that it doesn’t become an initiative or “good idea” with a limited lifespan. Instead, the road map becomes the rst step on the journey of continuous improvement in terms of staying focused, monitoring progress, and building the capacity of leaders and sta members along the way.

Maintaining focus on goals and key priorities is one of the most challenging aspects for schools and districts since multiple demands and pressures constantly bombard them. is is why it’s essential to maintain a level of simplicity in terms of what is necessary. Only then can districts mitigate those other strategies that begin to rob them of their focus, energy, and ability to sustain initiatives.

At the building level, focus and progress monitoring come in the form of ltering out distractions by staying committed to a limited number of the building committees. For example, one highly e ective principal used her three committees (Curriculum, Safety, and Wellness) to limit the number of new initiatives and monitor the progress of the current work around their PLC e orts.

At the district level, focus comes in the form of engaging district and building leaders in trimester feedback meetings at every school. Feedback meetings serve multiple purposes, but primarily, they give administrators an opportunity to reinforce the importance of implementing PLC principles, reviewing student data, monitoring overall progress,

and discussing challenges or obstacles. At the start of the school year, district and building administrators review the road map and clarify expectations and concerns. At subsequent meetings, the principal walks through the year’s priorities aligned to the road map, reviews student data that highlight the school’s progress using di erent data points, and states the next steps in terms of improvement. roughout the presentation, district administrators can ask clarifying questions and, more importantly, better understand how they can support the principal or sta . is process also ensures that the school district remains focused on the critical work despite any external pressures or distractions.

District administrators also face the challenge of nding time to build the capacity of leaders to guide sta members throughout the implementation continuum with limited professional development time in the school year. One school district altered their districtwide meetings to include a 15- to 30-minute professional development period to ensure they were building the capacity and expertise of every administrator. e new format allowed the district to also reinforce key messages, discuss new skills, and, most importantly, hear one common message.

While the journey to establish a districtwide Professional Learning Community at Work can be arduous, the foundational components are within reach of every district administrator. By developing district clarity, establishing a process for monitoring progress, and creating opportunities for administrators to develop their skills and knowledge, school districts can facilitate the implementation of districtwide PLCs. Sometimes it’s about starting with simple practices that will ensure greater levels of commitment from building administrators and sta as well as avoid frustration or surface-level implementation.

Reference

DuFour, R., DuFour, R., Eaker, R., & Many, T. (2010). Learning by doing: A handbook for Professional Learning Communities at Work (2nd ed.). Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Our shared vision for transforming education is 25 years strong

For more than two decades, Solution Tree has partnered with educators to achieve better results for students. Data af rms our professional development works.

Right now, schools and districts have ESSER II and ESSER III funds to spend. Our research-based solutions are ESSER II/III aligned and have proven track records for achieving academic excellence. Now is the time to realize your vision of success for every student.

The Size of a Team

Is there an optimum size for a teacher team?

Researchers have been unable to arrive at a consensus regarding the optimum size of a team. ere have been powerful teams of two—the Wright Brothers, Lennon and McCartney, and Brin and Page (the creators of Google). Large teams have also accomplished great things. Steve Jobs created a team of 50 people to develop the Macintosh computer. e Manhattan Project, which oversaw the creation of the atomic bomb, was the largest collaboration of scientists in the history of the United States up to that time. Over 150,000 engineers, contractors, military personnel, and construction workers contributed to the project. In her book Team Moon, Catherine immesh (2006) refers to the 400,000 people who worked on the Apollo 11 project as “the greatest team ever.”

It would, therefore, be completely arbitrary to attempt to declare the denitive optimum size for the collaborative teams within a PLC. It also would be foolish for eight teachers assigned to teach sophomore English to exclude one member from participating on the team because members had decided that seven was the optimum number.

e size of the team certainly impacts the way it operates. A team of 25 members will function di erently from one with four or ve members.

e larger team will likely divide tasks among smaller subgroups, convene more frequently in subgroups, and reserve larger team meetings for reviewing recommendations and making decisions. e important questions are, Do these teachers have shared responsibility for student learning? and Will they be asked to work interdependently to

achieve common goals for which members are mutually accountable?

Reference

immesh, C. (2006). Team moon: How 400,000 people landed Apollo 11 on the moon. New York: Houghton Mi in.

Have a question about PLCs? Check out Solution Tree’s e ort to collect and answer all of your questions in one great book: Concise Answers to Frequently Asked Questions About Professional Learning Communities at Work™ by Mike Mattos, Richard DuFour, Rebecca DuFour, Robert Eaker, and Thomas W. Many. This question and answer are in chapter 2, “Building a Collaborative Culture.”

Start With the , But Don’t Forget the

Begin With the

In recent years, there has been an increased emphasis on the importance of beginning improvement initiatives by focusing on the “why.” While much has been written about the importance of starting with the why, perhaps the most impactful work has been Simon Sinek’s (2009) book Start With the Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action Sinek observes that most leaders rarely focus on the why; rather, they focus on the “what” (actions that should be undertaken), followed by attention to the “how” (how to proceed). He writes, “Very few people or companies can clearly articulate the why they do what they do. When I say why, I don’t mean to make money— that’s a result. By why I mean what is your purpose, cause, or belief? Why does your company exist? Why do you get out of bed every morning? And why should anyone care?” (p. 39).

Michael Fullan and Joanne Quinn (2016) echo the importance of articulating the why, pointing out that “leaders need the ability to develop a shared moral purpose and meaning as well as a pathway for attaining that purpose. . . . Great leaders connect others to the reasons they became educators—their moral purpose” (p. 17). Anthony Muhammad and Luis F. Cruz (2019), as well as Richard DuFour et al. (2021), make the case that, to be e ective, leaders must e ectively communicate the why of the work since people tend to resist change to practice and lack motivation when leaders have not skillfully communicated the rationale for the work they are being asked to do.

Professional Learning Communities at Work and the

e Professional Learning Communities at Work process rests on the assumption that the why of schools—their core purpose—is to ensure high levels of learning for all students, and leaders seeking to capture the power of the Professional Learning Communities at Work model begin by engaging others in a process designed to clarify and communicate this central learning mission. Engaging others in clarifying and emphasizing the why provides many bene ts.

PROVIDES FOCUS FOR DECISION-MAKING

ere is no shortage of information school leaders must absorb. Much of the information requires decisions to be made—often quickly. Douglas Reeves and Robert Eaker (2019) note that so much information often results in fragmentation, and a school culture that is characterized by fragmentation and a lack of focus is associated with signi cantly lower levels of student learning— particularly among students from low-income families, students learning English, and special education students.

On the other hand, Reeves’s (2011) research suggests that focus resulting in a few high-priority, high-leverage initiatives is strongly related to gains in student learning. A sharp and consistent connection to the why is essential for developing a focused school culture and serves as a lter for decisionmaking and setting priorities.

PROVIDES THE MORAL AUTHORITY TO ACT

Clearly articulating and connecting to the why provides leaders with the moral authority to make decisions—to act. Absent this connection to the why, leaders are left with only the power of their position to hold others accountable. When asked why certain decisions are being made or various actions are being undertaken, by connecting to the why—the organization’s core purpose—leaders have a much more powerful tool at their disposal than simply “Because I said so!”

Not only does the why provide leaders with the moral authority to make decisions, it also creates conditions in which it becomes immoral not to act. Failure to implement commonsense, doable, high-leverage practices that move schools toward ful lling their moral purpose re ects a cruel indifference at best and malicious malpractice at worst.

TOUCHES THE EMOTIONS

Truly e ective leaders motivate and inspire, and they inspire others by constantly and consistently reminding them that they are part of a greater calling—a purpose worthy of their e orts. Sinek (2009) writes, “ ose who are able to inspire will create a following of people—supporters, voters, customers, workers—who act for the good of the whole not because they have to, but because they want to” (p. 7). In other words, connecting decision-making and actions to the why is an e ective way leaders tap into this higher calling of the profession.

Identify your values.

Dive Deep Into the !

Focusing on the why is much more than rewriting a school’s or district’s mission statement. It is the lens through which every initiative, every decision, every action, every interaction is examined. is implies not only a collaborative analysis of why priorities are being established but also a deep dive into practices that are either (a) resulting in only marginal results or (b) actually hindering student learning. E ective leaders bene t from establishing “why not” or “stop doing” lists to gain maximum results in limited time.

One rarely, if ever, hears educators complain of having too much time. On the other hand, it is not uncommon to hear that educators feel overwhelmed with the day-to-day expectations of being an e ective teacher or administrator given the plethora of seemingly never-ending initiatives, projects, and goals. Reeves and Eaker (2019) note educators “are in an endless game of Whac-A-Mole, attempting to hit every demand that arises, while not making progress on their most important priorities” (p. 1). Alexander Bant (2021) in Not Doing List points out that we all have the same amount of time each day, but highly e ective leaders have a di erent yes-to-no ratio. ey are clear about the things they will not spend time on.

How can schools decide what things they should stop doing?

In many schools, there are policies and practices that hinder or have a negative e ect on student learning. And many of these practices, such as averaging grades or allowing an unequal range between grades, remain relatively unexamined—especially by practitioners.

Examining the why-nots and creating stop-doing lists should be a collaborative process for analyzing initiatives, actions, and behaviors. In 100-Day Leaders, Reeves and Eaker (2019) propose a six-step process that includes identi cation, measurement, delegation, and elimination, which, if implemented with delity, results in focusing on priorities that can have the greatest impact on the why—improved student learning. e steps are (Reeves & Eaker, 2019, pp. 6–9):

Take an initiative inventory.

Make a not-to-do list.

Identify 100-day challenges.

Monitor high-leverage practices.

Specify results.

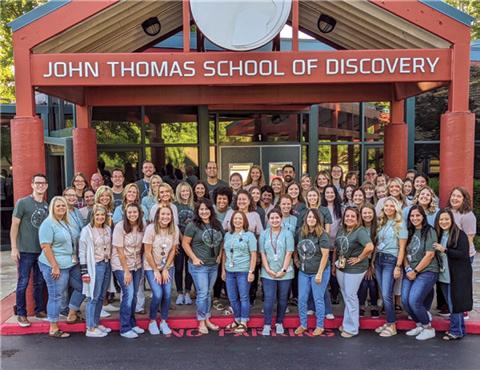

THE JOHN THOMAS SCHOOL OF DISCOVERY PLC Story

John Thomas School of Discovery (JTSD) was recently designated a Model PLC school. JTSD is a public K–6 laboratory school with a STEAM focus and is one of 12 schools within the 6,700-student Nixa Public Schools system. Nixa is a growing community located in southwest Missouri.

John omas School of Discovery launched in 2012. e idea of a laboratory school stemmed from declining test scores and low enrollment and as a response to the need for choice in public schools. e school was developed by inviting all stakeholders to the table to craft an innovative vision for what our school could become. roughout the

design year, 10 teams determined the critical features of our building, which include a STEAM focus, a nonevaluative lottery drawing from the entire district, an extended 20day calendar, a parent volunteer commitment, enhanced technology integration, and an enriched project-based learning environment. Our community rallied around us as we worked to create an innovative building focused on infusing the wonder of STEAM into everyday teaching and learning.

From the earliest days, we achieved growth and recognition as a highly collaborative building, focused on writing and teaching a quality curriculum for students and regularly

Jennifer Chastainsharing this progress with others through a range of training opportunities. We were recognized with various awards and continued to take risks and transform what school could look like for students. Despite this level of success, a review of our 2017 Missouri Assessment Program (MAP) scores provided impetus for change. Achievement levels were lower than what we were accustomed to, even with the state’s new assessment system causing scores to decline statewide. It was during this time our district also made the commitment to fully embrace Professional Learning Communities at Work. Looking back, the implementation of the PLC process was the key to our continued success at JTSD.

OUR PLC JOURNEY

e faculty at JTSD recognized change needed to take place, and we were ready to embrace a new opportunity. During a weekly schoolwide collaboration time, each sta member was asked to write down ideal characteristics of a JTSD student. is exercise led to many thought-provoking conversations and ultimately the revision of our mission, vision, and goals.

“Preparing STEAMazing Critical inkers for Life” became our driving mission. Each year, we collectively write three buildingwide goals focused on academic, social-emotional, and scienti c literacy.

At the same time, we realized that our two building leadership teams could be transformed into a guiding coalition. Our imPACT (curriculum) team continued to develop our guiding principles, while the STEAM (behavior) team developed our vision of how a JTSD student should behave, not only in the classroom but in all school settings.

Reinvigorated around a common purpose, we dove head rst into all things PLC. Our district provided numerous training sessions, while we worked as a team to understand how deepening our collaboration would lead us to greater success.

One thing to know about JTSD is that we are a building that does not do anything by a kit. Our curriculum is curated by educators with no script. So, honestly, there was some initial hesitation to fully embrace the PLC methodology. JTSD was given the charge to be innovative, to think outside the box, and now our district was requiring us to implement the PLC process. We were concerned this would sti e our creative spirit. Boy were we wrong! In fact, it did the opposite. Becoming a highly functioning PLC made us even better as a school family. It provided common language, common expectations, and the overall focus for what we were trying to accomplish. As a veteran administrator, I cannot imagine working in an environment that is not doing the PLC process right, as it provides the climate and learning environment that are best for students and educators.

Our commitment to the PLC process allowed us to better understand what e orts in our building were working and what should be abandoned. Over the course of our PLC

implementation, test scores have steadily increased, helping make us one of the top-performing elementary schools in the state of Missouri, all while remaining an innovative building with a tight-knit culture.

OUR STEPS TO PLC RIGHT

• A revised mission and vision. rough collaboration, our team redeveloped and re ned our purpose, creating statements that are easy to remember and carry out with our families.

• Collective commitments and buildingwide goals. Our team de ned our collective beliefs so that we all understand our expectations of success at JTSD. We then set goals that allowed us to strive toward our mission and vision.

• JTSD strategic plan. All stakeholders came to one table to create a strategic plan that mirrored our district’s school improvement plan. is process created a ve-year action plan for our school’s goals.

• PADI (pacing, assessment, data, intervention). is document, along with ongoing training, provided clarity, objectives, and tasks to assist teams in answering the four critical questions of a PLC.

• PLT (professional learning team) agendas revised to include major elements of PLCs. Teams began collaborating with a purpose. Each team used a similar agenda format to ensure we comprehensively covered all necessary aspects of Tier 1 instruction. is agenda included a team goal, which outlined how each team in our building would contribute to our overall building goals for the year.

levels of performance. For example, our third-grade team collaborates to form groups of students to work on a variety of recently assessed priority standards. e groups are exible and can be changed at any time to meet the needs of students. Our third-grade team has met with our fth-grade team to share ideas and successes, exemplifying our culture of collaboration throughout the building.

JTSD developed an innovative approach to student intervention and extension during the school’s extended June session (Summer STEAM @ JTSD). Monthly benchmark testing was utilized to identify student learning needs in English language arts and mathematics based on priority standards. Students who needed social-emotional support were also identi ed by the school counselor. e master schedule was modi ed to allow all grade levels to have the same intervention time and provide more sta with opportunities to be involved. Weekly sta collaboration time allowed teachers to plan their projects and prepare. Teachers and sta utilized project-based learning to provide student learning interventions and extensions that made learning fun and engaging. For example, fourth-grade students who needed English language arts intervention were provided extra support by planning and performing a poetry slam for teachers and family members. To gauge the bene t of this endeavor, students took an assessment at the end of June to determine the success of the interventions and extensions.

KEYS TO SUCCESS

As a 26-year veteran in education, if I were to pinpoint one aspect that has had the greatest impact, I would honestly have to say it is the work done to become a professional learning community. When I asked our guiding coalition what they felt were the keys to our success at JTSD, they said rst and foremost was our true collaborative culture. Our team rallies together to create a learning culture focused on the right things. Being transparent and vulnerable are also essential to our mission. is transparency and vulnerability creates trust, and without trust among the teams, true excellence cannot occur. And lastly, our team felt that our re ective nature leads to success. We are constantly looking at the data to determine what is best for our students and for our teachers. I am forever grateful for our PLC journey. As I leave this amazing school after eight years as lead learner, I know that through the shared leadership created by our strong professional learning community, JTSD will continue to prepare STEAMazing critical thinkers for life.

DR. JENNIFER CHASTAIN IS THE PROUD PRINCIPAL OF JTSD.

DR. JENNIFER CHASTAIN IS THE PROUD PRINCIPAL OF JTSD.

Words Matter

WHAT IS A LEARNING-FOCUSED MISSION?

As educators, are we here to teach and cover a curriculum, or are we here to ensure students actually learn the curriculum? A learningfocused mission assumes that our schools were not built so educators have a place to teach but instead so students have a place to learn. In the PLC process, the rst big idea, a focus on learning, captures this belief. e fundamental purpose of a PLC is to ensure high levels of learning for every student.

e PLC process is a way of thinking. Getting educators to shift from a mindset of teaching, covering material, ranking, and sorting to learning for all is a di cult task. Once a school embraces this mission and understands the new lenses through which one must view the work, traditional practices that are counterproductive to this goal become apparent.

ink of this shift in mindset as similar to the experience of looking at an optical illusion. First you see the obvious picture, like a beach scene, but after you examine the image long enough, you start to view it another way. A new picture emerges of an elephant in a clown car. Once you get it, you think, “How did I miss that elephant?” Until you mastered the ability to look at the picture with the correct gaze, it really did look like a traditional beach scene. at is what the shift from a teaching focus to a learning focus is like.

Source: Mattos, M., DuFour, R., DuFour, R., Eaker, R., & Many, T. W. (2016). Frequently asked questions about Professional Learning Communities at Work Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Why I Love PLCs Perfecting the Practice

BY JENNIFER BURRIS

BY JENNIFER BURRIS

“How do you support rst-year teachers?” When asked this recently, I was quite surprised that an applicant with no teaching experience would know the signi cance of this question. At the conclusion of the interview, I found myself thinking about what my response would have been prior to PLCs.

I can vividly remember when I accepted my rst teaching position. I was given a key to my classroom, a teacher’s edition of the textbook, class rosters, and a genuine “Good luck!” My classroom was right across the hall from a teacher who was teaching the exact same thing. What is now mind-blowing to me is that the two of us worked in complete isolation for the entire school year. Why? at’s the way it was always done.

It was common for schools to have a culture of complacency. Complacency is de ned as self-satisfaction, especially when accompanied by unawareness of actual deciencies. We didn’t know better! I have heard many times throughout my career “You don’t know what you don’t know.”

Twelve years later, one event wouldnally reveal there was indeed a better way.

e PLCs at Work Summit launched our PLC journey. e biggest takeaway was the four critical questions of a PLC, which transformed our educational practices as we had known them.

What do we want students to learn? Before the PLC process was implemented, it was common practice for teachers to operate under the assumption that all standards are equally important and therefore attempt to cover each one for the same amount of time, not realizing that this inch-deepand-mile-long approach results in students

with signi cant gaps who are not prepared for what’s next. After the PLC process was implemented, it became common practice for teams to collaborate during common planning time to identify high-priority standards. Once this has been done, teams move forward with building high-quality assessments that have a strong emphasis on these essential standards.

How will we know if they learned it? Before the PLC process, it was common practice for teachers to teach an entire unit before assessing to see if the students actually grasped the concepts. After the unit test, they moved on to the next unit. is approach left so many kids behind with no system to catch them up. With the PLC process, our teams now create common formative assessments (CFAs) that prioritize the essential standards and administer those CFAs throughout the unit. ey use these assessments to identify struggling students and provide support before they get to the unit test and it’s too late.

What will we do if they don’t learn it? Before the PLC process, it was common practice for teachers just to move on. After all, there is a pacing guide and teachers don’t have time to go back and reteach an entire unit. With the PLC process, teams now use the CFA data throughout the unit to determine which students need help with which standards and then provide immediate, targeted support during time that is built into the instructional day. After students receive additional support, often from a teacher other than their own, they have a chance to retest. What a growth mindset!

What will we do if they have learned it? Before the PLC process, the response would

be the same as when they don’t learn it: give them a grade and move on to the next lesson. is approach doesn’t give pro cient students an opportunity to take their learning to a higher level. With the PLC process, teams now create rigorous extension lessons to stretch students’ learning while those who are struggling are provided additional support.

So, how do we support rst-year teachers? Before we were a PLC, I would have had very little to share with a brand-new teacher posing this question. Now that we’ve become a PLC, I can’t hold back my enthusiasm as I respond. e answer is quite simple. We give them the most valuable resource—each other! We plug them into our high-functioning PLC that fosters a culture of collaboration and promotes success as we work to ensure high levels of learning for all. at’s why I love PLCs!