5 minute read

The Chinese Baptist Church and Mission School in Cleveland, Mississippi

Photo Essay

Intégrité: A Faith and Learning Journal Vol. 19, No. 1 (Spring 2020): 66-74

Advertisement

John Zheng

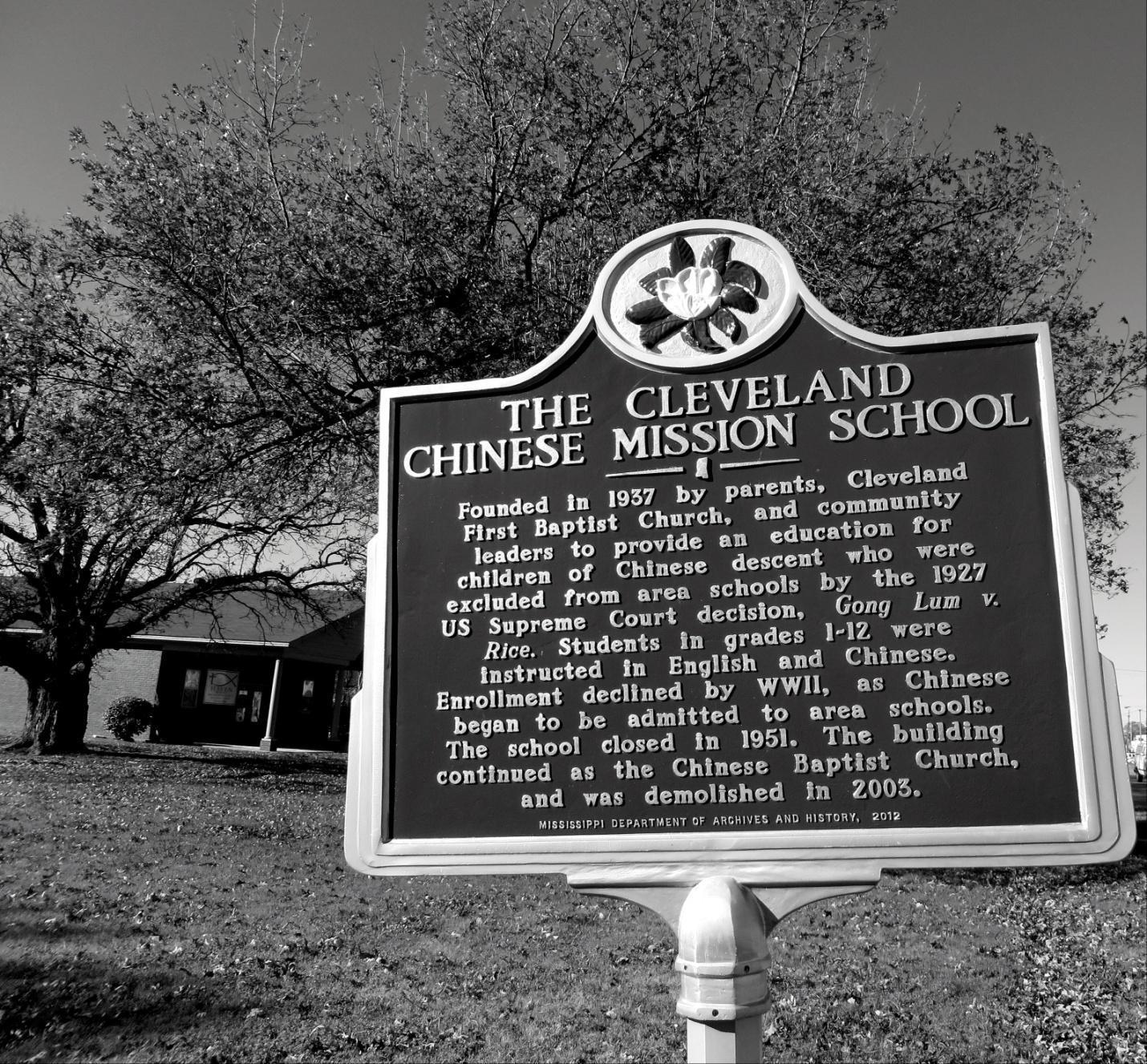

Recruited by planters to replace freed African American laborers after the Civil War, the first Chinese immigrants, who might have been laborious workers for the transcontinental railroad, set foot on the Mississippi Delta. They came with the purpose to make money so that they could live a better life when they returned to China. Once they realized they couldn’t make money from laboring in the cotton fields, the Chinese resorted to opening grocery stores to achieve business success. An early Chinese immigrant who arrived in the Delta was Wong On. Born near Canton, China, in 1844, Wong arrived in California in 1860 to help build the transcontinental railroad. After moving to the Mississippi Delta to pick cotton, Wong married a black woman and opened a store in Stoneville (Wilson). Soon more Chinese arrived, particularly in the early decades of the twentieth century. Most of them were the immigrants’ relatives or sons from China. Their grocery stores were successfully established in the communities through a family system that passed business from father to son. When more Chinese immigrants settled down in the Delta and established families, education became an urgent need for their children. But, during the hard times of segregation, Chinese children were excluded from white public schools even though Delta Chinese wished to be assimilated. When Chinese children were excluded from local all-white schools by the 1927 US Supreme Court decision, Gong Lum v. Rice, Chinese parents, the First Baptist Church, and community leaders worked together to found a boarding mission school in Cleveland in 1937 to provide an educational haven for dozens of Chinese students in the central Delta. It offered classes in English, Chinese, math, spelling, reading, and history from 8:30 in the morning and ended at 3:00 or 4:00 in the afternoon. Some students boarded at school while others went home after school. The mission school, supported by the Baptist Church, desired also to introduce the Chinese students to Christianity. Unfortunately, the school was closed in 1951 when Chinese children had a chance to attend public schools in the Delta. In the difficult years when Chinese immigrants worked hard to maintain business and raise children in the Delta, the Baptist Church played a central role for generations, particularly the Chinese Baptist Church in Cleveland (Figures 1

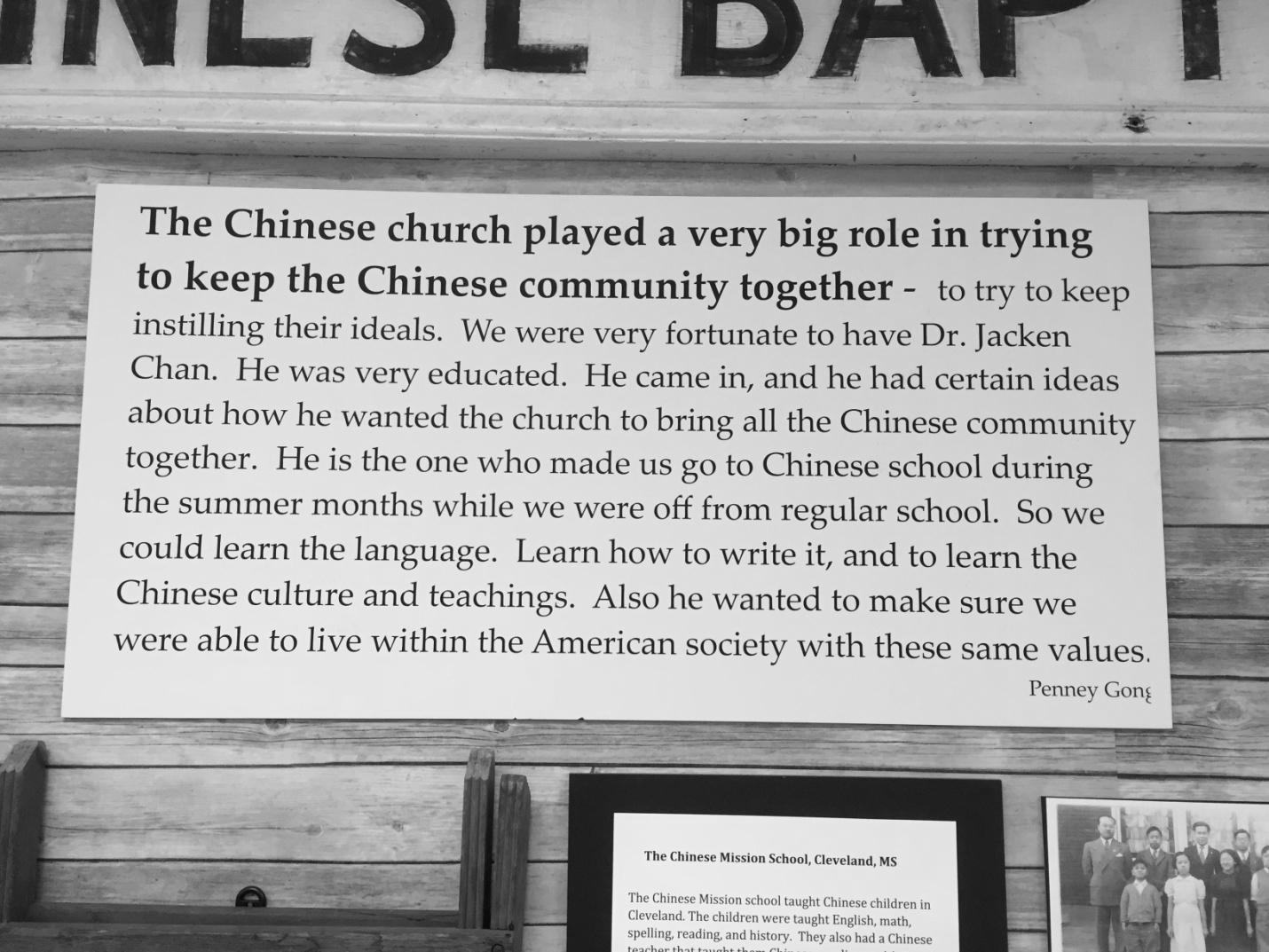

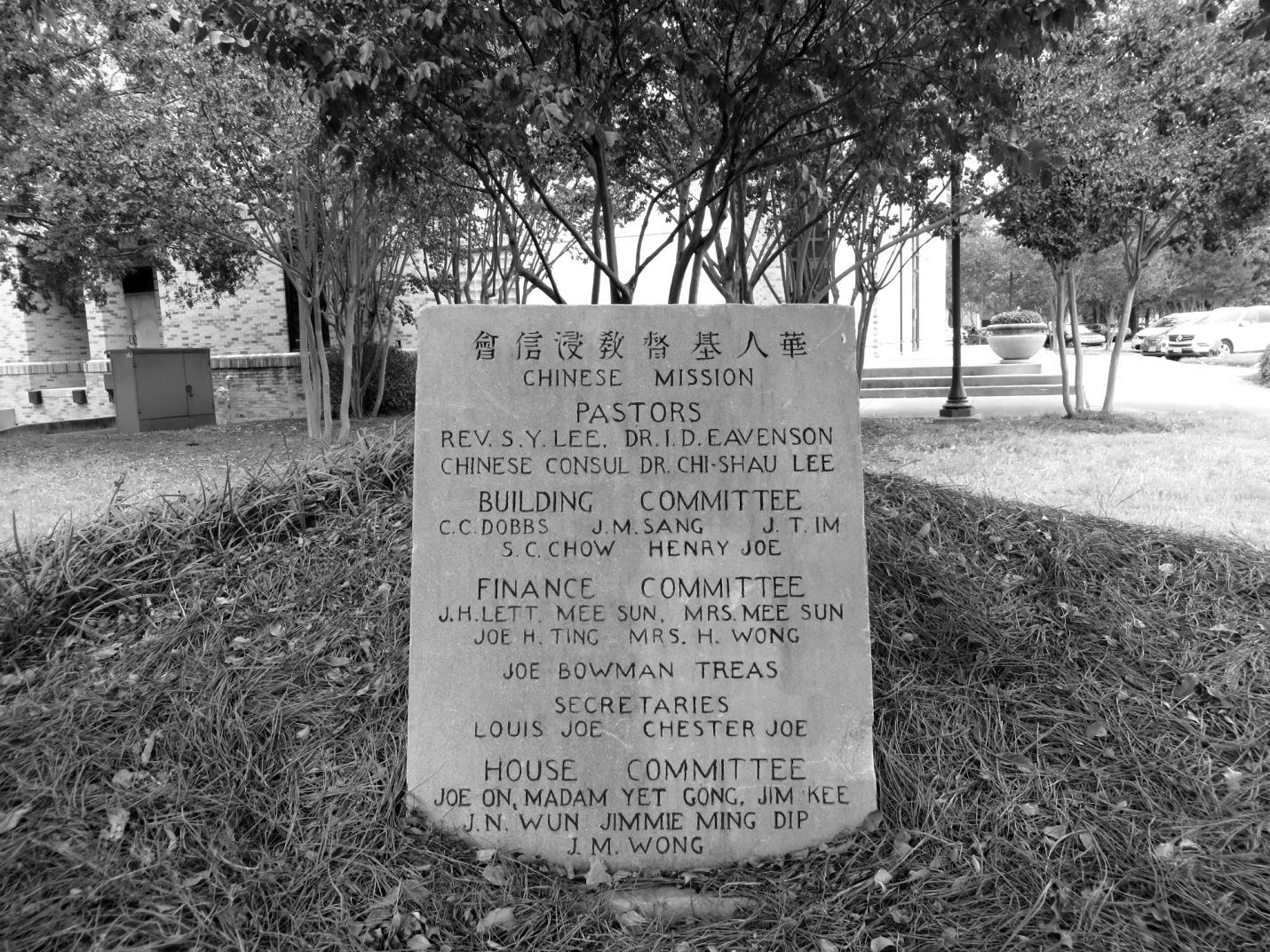

and 2), which “served as a center for wedding banquets, community service projects, fundraising activities, funerals, and other occasions that brought the extended Chinese community together” (Wilson). This church stopped providing service when most of the younger generations of Delta Chinese began to move out of the region. Later it was remodeled into the Haven Hospice and Palliative Care building. Now the church cornerstone (Figure 3) is preserved outside the Capps Archives & Museum building at Delta State University, and the church tablet (Figure 4) is displayed in the Mississippi Delta Chinese Heritage Museum housed on the third floor of the Capps building. The Chinese Mission School in Cleveland (Figure 5), which used to stand close to the Chinese Baptist Church, no longer exists either. On its site, a historic marker indicates the bygone building (Figure 6). I photographed the Chinese Baptist Church and the Mission School in 1997, a year after I relocated to the Delta. One Saturday as I approached the town, the church and the mission school immediately caught my attention, particularly the school. Its peeled yellow paint and boarded-up windows were eerily impressive with stains of old days. Some years later when I drove back with a desire to photograph the Mission School, especially its marble tablet with inscriptions on the wall, it was no longer extant. It might have been an “eyesore” to the landscape, so it was demolished in 2003, but its history has been preserved through films, books, articles, and recordings. It was lucky that I had grabbed a shot of both buildings before they disappeared from sight. One noticeable thing is that research on Delta Chinese seems to have flourished in the twenty-first century. Chopsticks in the Land of Cotton: Lives of Mississippi Delta Chinese Grocers by John Jung was published in 2008; Journey Stories from the Chinese Mission School, edited and compiled by Paul Wong and Doris Ling Lee, was published in 2011; The Mississippi Chinese Veterans of World War II: A Delta Tribute, edited by Gwendolyn Gong, John Henry Powers, and Devereux Gong Powers, was published by Delta State University Archives & Museum in 2015; Honor and Duty: The Mississippi Delta Chinese, a film in three parts covering the history of Delta Chinese from 1870 to the present, was released as a heritage series in 2016; and Water Tossing Boulders: How a Family of Chinese Immigrants Led the First Fight to Desegregate Schools in the Jim Crow South by Adrienne Berard was published in 2017.

In October 2012, through the initiative of Raymond Wong, Frieda Quon, and a group of others, Delta State University opened the Mississippi Delta Chinese Heritage Museum to promote “the local heritage preservation by actively collecting oral histories, memorabilia, photographs and textile materials related to the history and story of the Mississippi Delta Chinese immigration and settlement.” Its goal is to preserve cultural resources which will disappear through the changes of Delta migration and economy in order to “encourage an environment of understanding and appreciation of our ethnic and cultural diversity” (“Museum Information”). The opening of the Mississippi Delta Chinese Heritage Museum is a capstone to future projects on the history of Delta Chinese. Personally, I wish a book on the Chinese Baptist Church would come

out soon to serve as an addition to the study of Delta Chinese and to be a window for the reader to catch a glimpse of their spiritual world.

Works Cited

“Museum Information.” The Mississippi Delta Chinese Museum. http://www.deltastate.edu/library/departments/archives-museum/guidesto-the-collection/ms-delta-chinese-heritage-museum/. Wilson, Charles Reagan. “Chinese in Mississippi: An Ethnic People in a Biracial Society.” Mississippi History Now. http://mshistorynow.mdah.state.ms.us/articles/86/mississippi-chinese-anethnic-people-in-a-biracial-society.

Figure 1. The Chinese Baptist Church by Highway 8, Cleveland, MS. Photograph by John Zheng, 1997.

Figure 2. Penney Gong’s note on the Chinese Baptist Church. Photograph by John Zheng, 2017.

Figure 3. The Chinese Baptist Church cornerstone, Cleveland, MS. Photograph by John Zheng, 2017.

Figure 4. The Chinese Baptist Church tablet, Cleveland, MS. Photograph by John Zheng, 2017.

Figure 5. Chinese Mission School, Cleveland, MS. Photograph by John Zheng, 1997.

Figure 6. The Chinese Mission School Marker, Cleveland, MS. Photograph by John Zheng, 2015.