5 minute read

ASK MCGEHEE

What’s the story of the building on St. Francis Street inscribed “First National Bank?”

text by TOM MCGEHEE

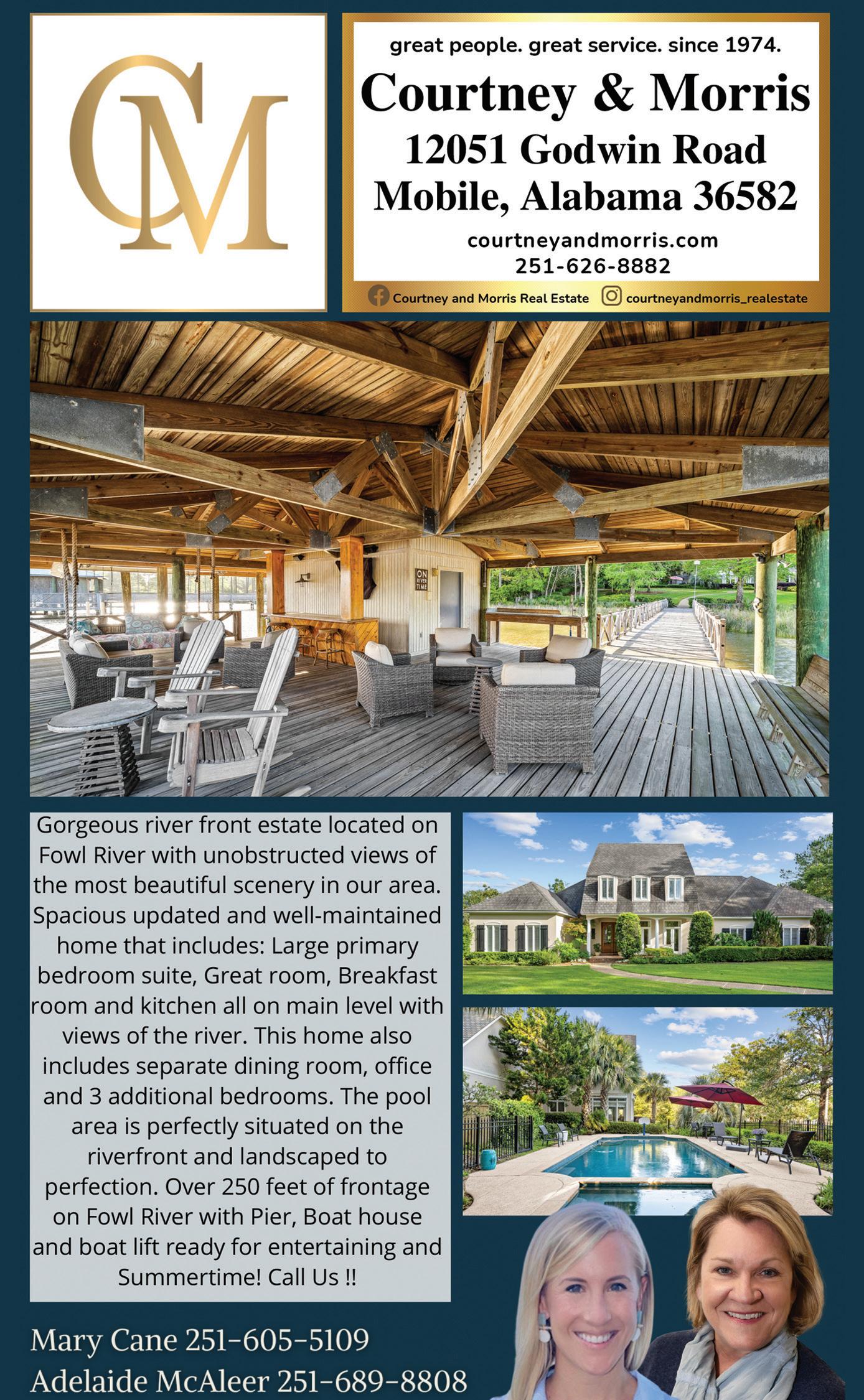

Advertisement

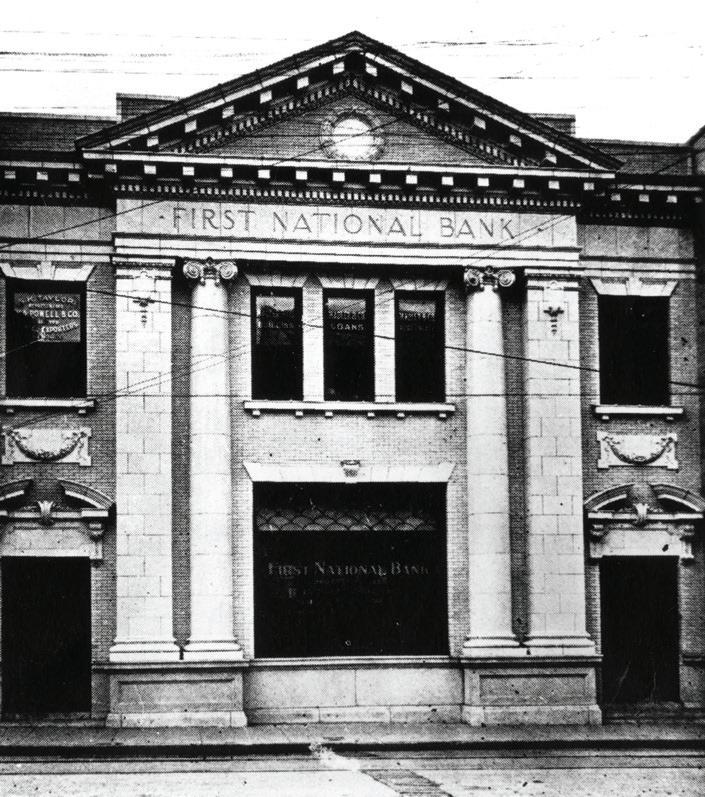

Above In 1906, Mobile’s venerated First National Bank requested a building that would reflect their solidity, but they occupied it but a brief time.

Although Mobile’s First National Bank will long be identified with the skyscraper which is now home to the New Year’s MoonPie, the bank had a few former homes. This is not surprising for a bank which was founded back in 1865 and had the distinction of being the state’s oldest existing bank for generations.

The year 1865 seems an unlikely one for the start of a bank. Barely a month after Lee’s surrender, a group of 25 businessmen met in the original Battle House Hotel and organized it. The First National opened within an impressive columned Greek revival building at the northwest corner of St. Francis and Royal streets. Ironically, it had been built in 1832 to house a bank. That bank was short-lived.

In 1870, the bank’s new president was James Masson, who had previously been listed as a “money broker.” It is unclear why the First National moved, but by 1872, it was listed at 40 St. Francis Street in a far more modest storefront. According to city directories, there were at least four banks operating in that vicinity, including the Deposit Savings Bank next door at 38 St. Francis Street.

As the decades passed, the First National survived while many of its competitors did not. There were national panics, and other banks had runs on their deposits. One of the most famous occurred in July of 1884 when the city’s oldest, the Bank of Mobile, had a run and promptly closed its doors after 66 years.

Mr. Masson resigned in 1904 due to what the bank claimed was “ill health.” After a very nasty divorce, Masson remarried a younger woman and took a trip around the world where he died — some say rather mysteriously — in Kyoto, Japan.

A New President and a New Home

The bank’s newly elected president was Henry Hall, and it was under his leadership that the bank sought a new look. Between 1902 and 1906, a half dozen banks were being built or renovated in Mobile, and apparently the management of the First National Bank felt they needed to keep up with the competition.

A recently formed architectural firm was hired — Watkins, Hutchisson and Garvin. Of the three, only Clarence Hutchisson was a Mobilian. George Watkins had designed numerous buildings in Buffalo, New York, and Erie, Pennsylvania, before arriving in Mobile in the mid-1890s. Little is known about Joseph Garvin. Described by some sources as an engineer, his name only appears in Mobile’s city directories between 1906 and 1910.

Perhaps the bankers admired the firm’s latest creation, the Cawthon Hotel on Bienville Square. In any event, their instructions were extremely specific in what they desired. All of Mobile was admiring the gleaming white skyscraper of the City Bank and Trust Co. fronting on Royal Street. It stood seven stories, contained high-speed elevators, and its marble-clad lobby was the most elegant in town.

The structure housing the First National Bank would not be a skyscraper. The bankers considered the new skyscrapers as too new, too commercial and just downright revolutionary. They demanded a design that stressed dependability and the firm’s solidity, using recognizable classical design elements. It must declare the firmness of the business being conducted within its fireproof walls while containing the city’s most burglarproof vault.

Inspired by Antiquity

In 1906, the old row of storefronts that housed the bank was demolished. A two-story, temple-like structure fronted with white-glazed terra cotta was built in its place. Steel beams and reinforced concrete were used in its construction.

The first floor held the bank lobby featuring green marble wainscoting seven feet in height. Above this was green burlap wallpaper stenciled in a gold design. The tellers’ counters were of white marble fronted with gleaming bronze grills. The floor was of mosaic tiles, and mahogany desks were placed for the convenience of customers.

The main floor also contained a meeting room for the board of directors. No expense had been spared, and an artist from St. Louis

was hired to paint the ceiling mural. The second floor held 15 offices while the rear wing contained space for the employees, including locker rooms and an area for their breaks and lunches.

Mobile’s City Bank and Trust grew rapidly and enlarged its building with the help of George B. Rogers. A spectacular run on deposits in November of 1915 led to its demise. The First National Bank, which had occupied this monument to solidity for only eight years, opted for a former competitor’s skyscraper and would occupy it for nearly 50 years.

Alabama Power’s New Home

The dignified bank building on St. Francis Street was converted into an office space before the Mobile Electric Company bought it in the early 1920s. In 1925, that firm merged with Alabama Power Company, and the refined banking lobby became a retail store for an assortment of electric appliances, including monitor top refrigerators and stoves on graceful metal legs.

Alabama Power Company kept their offices and retail store at this address for more than three decades, moving to St. Joseph Street in the late 1950s. Bidgood Stationery operated in the building after that.

First National Bank, which was the oldest bank in the state and occupied the tallest skyscraper in Alabama, merged with Birmingham-based AmSouth in 1985. Number 68 St. Francis became a bank again soon after when former executives of the First National had it remodeled to house the newest Bank of Mobile.

Although that bank was formed to promote the idea of a hometown bank, it was ultimately sold to out-of-state interests. The white terra cotta still gleams on the facade of the 1907 structure, but it eagerly awaits a new tenant and a new purpose. MB