12 minute read

MOJATU INTERVIEW WITH PSYCHOTHERAPIST

By Mr. Nur Mohamed

sitting there I feel I have so many enriching experiences that add to my counselling.

Advertisement

More importantly I kind of feel like everything I have been through kind of helped me to be counsellor and everything I have been through kind of makes sense when a client is sitting on that chair because everything I been through makes sense when I work with clients and it helps my clients and myself to understand what they going through and to show more empathy and cultural awareness in many ways.

3. Mojatu: How would you describe coaching to a total stranger?

Counsellor: The best way I can describe counselling to total strangers is that we strive from the day we are born to the day we go to nursery to school to college to university to get knowledge of the world. But counselling helps you with the knowledge of within, the knowledge of oneself, the knowledge which enables you to have true knowledge because only by knowing yourself will you truly get to understand your own universe and your perception of reality and because we didn’t see the world as it is but as we are so for us to understand the world we need to understand ourselves and this a wisdom. In some cases, the real, true knowledge is the knowledge of oneself, knowledge of emotion through intelligence is intelligence of oneself. So, counselling helps you in every aspect of your life.

Being thankful to God, I am so grateful to be a counsellor but I think without it I wouldn’t the son, the husband and the father that I am to my family because it made me able to accept my family for who they are and accept myself for who I am and understand what I am able to do and what I am not able to do and in many ways it kind of makes understand religion in better context.

4. Mojatu: From your experience, who in our communities is mental health affecting?

Counsellor: I think mental health impacts everyone in our community but in recent years is impacting the young generation a lot more than ever before –this being due to the isolation and loneliness they find themselves in and the pressure they feel coming to them from the society expecting them to be successful. Social media is constantly bombarding them with false notions of how to adopt a get-richquick approach and become millionaires. On top of that, the family responsibilities they must bear, the crisis of the social media crisis, the peer pressure.

All of these make it difficult for them to navigate their way as to who they are and the society they are part of. Especially unique for the Somali youth they many a times feel lost in terms of their identity – which one are they first: Somali, Muslim, Black or British. These days it is really impacting today’s generous, particularly those under the age of 25 feeling confused about how to strike a balance between these seemingly mutually contradictory identities. They are feeling heartbroken by lots of unfulfilled hopes, the split-up with parents, the impact left behind the COVID Pandemic in the loss of loved ones.

There are a host of issues the youth are facing and are not finding the right people to talk to. The language and cultural barriers and the lack of proper communication between them and their parents further exacerbate their difficulties that is why you see these days it is the youth who are quite disproportionately impacted by mental health, not denying the fact that older people are also affected by it. As Black and from a refugee background, we have the highest number of people suffering from mental health.

5. Mojatu: From your experience, what are the main drivers of mental health problems among the youth?

Counsellor: I think the main issue is stigma, not willing to accept that mental health can have an impact on them. They might know it and don’t believe in it. Even when they seek help, they are afraid to be stigmatised, to be called weak, not practising, not knowing to seek help or afraid to seek help. Not understanding the full information about it. Stigma is the biggest issue of mental health in our communities. Educational mental health is a lot more in our communities and to be recognised that it is not due to lack of spirituality but an illness like any other illness.

6. Mojatu: What advice would you give to parents, young adults, and local authorities to provide holistic protection and support to those affected by mental health?

Counsellor: The best advice I can give to parents, first, is to educate themselves about what mental health is and to be cognizant of the isolation they feel, or being erratic, or failing in school or change of habits. I want to understand the triggers of mental health without discriminating or putting unnecessary pressure on the young people. As far as the authorities are concerned, they need to invest in the people and community organisations directly involved and doing the groundwork.

They need to develop relationships with the service providers such as community groups, mosques in order to give the financial support where it is needed and provide them training to build their capacity and skills needed to improve the work they do. It must be something that has longevity so the youth can understand the stigma attached to mental health and for it to become something openly spoken of and discussed.

The authorities need to go to the communities and not the other way round. This is the only way that mental issues of the ethnic minorities can be brought down. There was a long report we prepared about mental health and made recommendations on what to do about it which wasn’t implemented and needs to be implemented and there should be community-led projects which have longevity and enjoy the support of local authorities.

I think that is the best way and the people who are directly dealing with it must be culturally aware. The counsellors, mental health workers should be from the community.

7. Mojatu: Overall, what policy options would you recommend being put in place to support young adults and take them off the street?

Counsellor: I think the best policy to have in place a counsellor in every school. I think that is the best thing to do, especially today’s society. Not just a counsellor for the sake of it and a counsellor who is representative of the young people they are helping. The waiting list in the NHS is very long and there are no counsellors at the schools. I think mental health should be prioritised, especially talking therapy, longterm therapy which are areas very much needed.

DEALING WITH DEPRESSION: IMPROVING ACCESS TO PSYCHOLOGICAL THERAPY SERVICES

By Ladan Osman

In Great Britain, one in six people in the general population experiences depression. Still, some groups within the Black and Asian Minority Ethnic (BAME), compared to the White British, are expected to have higher mental illness rates. Symptoms of depression can broadly be categorised as low mood, decreased social interactions and poor functioning.

In addition, cultural beliefs influence how individuals experience symptoms and how it manifests through emotions, thoughts, and behaviours. Therefore, it is ever more pertinent to consider different cultural perceptions of depression. For example, Black and Africans could view symptoms as having less severe consequences, whereas Muslims from South Asia may link depression to spiritual weakness. Another essential factor to consider is gender disparity.

Society deems males self-reliant to cope with difficult circumstances, including psychological distress. The generational gap further compounds this, i.e., older adults believe psychotherapy is futile. All these misconceptions contribute to a lack of helpseeking behaviour resulting in underutilised primary healthcare services.

Improving Access to Psychological Therapy (IAPT) is part of the NHS England services that provide shortterm talking therapy. The evidence-based treatment, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, can relieve common mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety and PTSD2. People over the age of 16 years can self-refer, or the GP can send a referral.

However, the Health Inequalities Research Group found that the BAME community face several barriers to accessing IAPT through self-referral compared to their White British counterparts5. Instead, referral pathways are often via community services such as public employment agencies, educational provision, and criminal justice.

Furthermore, patients may describe pain, headaches, and difficulty breathing during GP consultation rather than emotional presentation6. Thus, it is difficult for the doctor to detect psychological distress in ethnic minority groups. In those incidences where the doctor recognises mental health problems and guides the patient to self-refer via IAPT could lead to feeling dismissed or un-prioritised.

A social network is a catalyst to the extent a person engages with mental health services6. For example, people of South Asian ethnic origin might struggle to confide with family and friends about the diagnosis. Stigma causes fear that the family’s status may affect financial opportunity and community interaction. As for Black and African Caribbean, mistrust of the healthcare system could derive from overrepresentation in specialist services. This group are four times more likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act compared to White British, Chinese and Indian.

The Health Inequalities Research Group reports that barriers continue during the assessment and treatment at IAPT. For example, primary health clinicians may perceive referral via community service as an unwillingness to take ownership of health or a sign that unmet needs have been unmet. As such, the individual might be more likely to be referred to other services prolonging treatment, thereby intensifying symptoms. In addition, the psychometric scale uses a western understanding of depression, which loses meaning once translated into other languages.

If a person requires translation during talking therapy, they can request interpreters. However, it is essential to remember that depending on availability and delays could prolong the treatment course.

Living Poor In A Wealthy Nation

- By Omar Mohammed

Generally, poverty can be defined as when people confront challenges to match their scarce resources with their unlimited wants and needs. The many wants that people, usually the poor, worry about include getting enough and nutritious food, costs of utilities, transportation to attend various services and saving a given percentage of their income for unexpected emergencies.

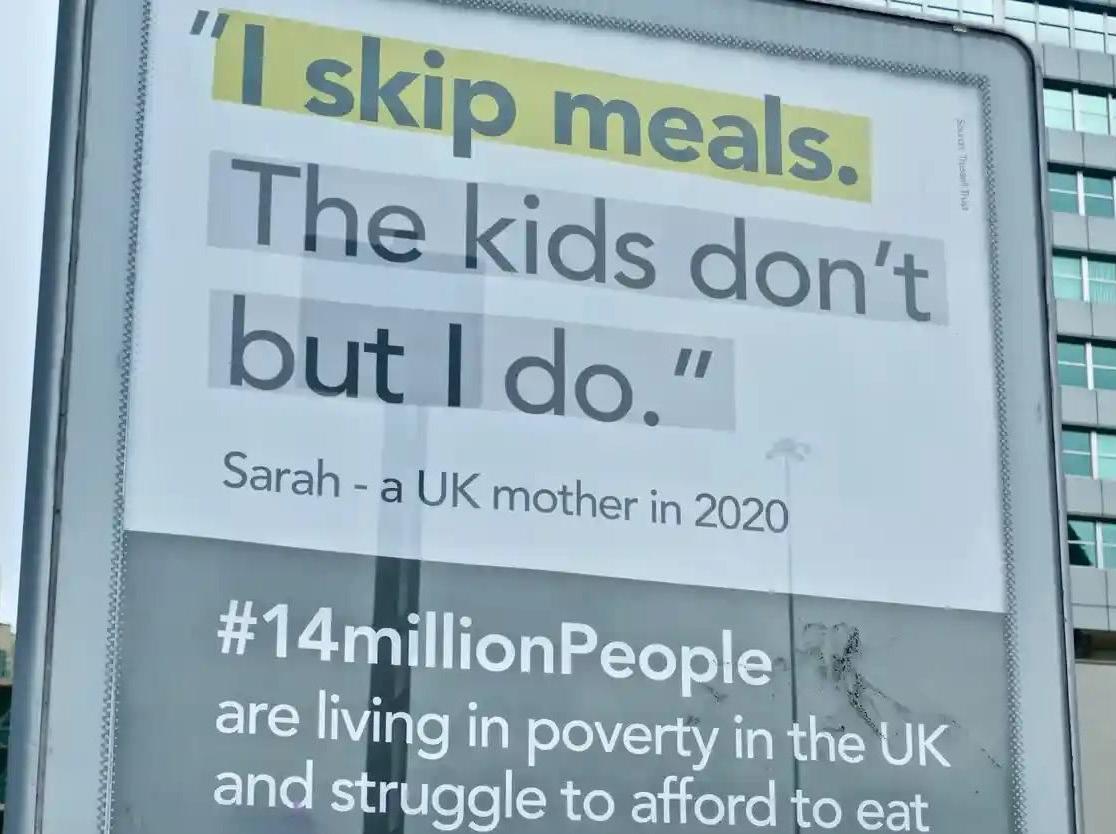

In the UK, however, the government defines a person or household as poor when they live with an income that is 60 percent lower than the average UK income. According to this definition, currently there are one in sex people in the UK who live poor. Alarmingly,

Because the rate has been steady in the last few years, it further varies between different population groups, depicting that the standards of living and gaps between the poorest and middle-income households have not really improved in recent years. UK poverty statistics reveal that minority communities remain the highest among those households living with poverty in the country.

A. K. is forty-five years old, social renter and working father of 6 kids, youngest being just over two years old. He explains to us that soaring costs of living have worsened their living standards particularly in the winter. Though household income has not changed, the costs of basic food, energy have drastically increased, which made his family rethink their shopping and eating habits.

He told the Mojatu Magazine team that with such heavily constrained household budgets, the family grapples with meeting the very basic living conditions and let other innumerable needs, that would be essential for the kid’s welfare and growth, to forgo. He adds that for the last several months, despite government energy support, he was unable to fully pay his energy bills. Statistics show that children from poverty-stricken communities suffer the most, they worry a lot, suffer unhappiness, and feel embarrassed in their schools and other social environments.

While households and families live with extreme levels of stress, so do community-based organisations.

A community centre in northern London, with over ten years of service have as well added their concerns of shrinking of funds. They told our team that they have complexities in meeting basic running costs let alone to offer services to minority communities.

The centre adds that accessing public funds and securing government grants has become difficult.

As a result, they initiative fundraising plans that will aid them keep their doors open for providing the very needed counselling, mentoring, and training services they extend to local communities.

In a nutshell, the 2020 pandemic has reversed all good work and progress made to reduce the rate and effects of deprivation, it further uncovered how the existing support agencies and policies are shaky and any economic successes can be ripped off with pandemics and social crises.

The guardian reports that those living with relative poverty have increased from 13 percent in 2010 to over 17 percent in 2020. As a result, for working parents, prosperity would remain a desire but far from being attainable.

WHY DO MINORITY OWNED BUSINESSES FAIL?

By Saida Egeh

Lack of Training on Small Business and particularly minority owned businesses remains the major obstacle many start-ups and other small businesses are experiencing.

Small businesses are the backbone of the economy, contributing to job creation, innovation, and economic growth. However, many small businesses struggle to survive due to various challenges, including a lack of training. Without proper training, small businesses may not be able to operate efficiently, leading to financial instability and ultimately, failure. In this article, we will explore how the lack of training can impact the financial stability of small businesses and examine what Islington Council is doing to support black-owned small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in their community.

Small businesses that lack training often struggle with inefficient operations. This can result in wasted time, resources, and money, leading to decreased profitability. Without proper training, employees may not know how to perform their jobs efficiently, leading to delays, missed deadlines, and dissatisfied customers. Additionally, untrained employees may need more supervision, which can take time away from other important tasks, further decreasing productivity.

A lack of training can also lead to errors in recordkeeping, billing, and inventory management, further contributing to financial instability. Small businesses that lack training may also struggle with ineffective marketing strategies. Without training in marketing and advertising, businesses may not know how to effectively reach their target audience, resulting in reduced sales and revenue. A lack of training may also lead to ineffective branding, messaging, and customer engagement, further decreasing the business’s financial stability.

The UK government and local authorities have recognized the importance of supporting blackowned small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in their local community. They have taken several initiatives to help these businesses thrive. However, what makes level accessibility difficult is the lack of local business networks and grass roots initiative, that would support business make of these government initiatives and mobilise local business communities.

In conclusion, the lack of training can have significant impacts on the financial stability of small businesses. Inefficient operations, reduced productivity, ineffective marketing, high employee turnover, and missed opportunities can all contribute to financial instability and ultimately, failure.

However, various government initiatives to support black-owned SMEs demonstrate a commitment to promoting diversity and inclusion in the local economy. But skills gap, lack of access to digital systems, finances and research remains the most cited challenges many minorities owned businesses are to deal with.

Dwp To Provide Extra Cash To Local Authorities For At Risk Families Until March End 2024

By Peter Makossah

Government through the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) says the most vulnerable would receive direct payments in 2023/24, which include up to £900 delivered in three payments to those on means-tested benefits, and a £150 payment for those on disability benefits, and £300 on top of Winter Fuel Payments for pensioner households.

According to DWP the scheme comes on top of ‘extensive support for those in need in the coming months.

A staggering £842m boost poured to the Household Support Fund will see millions of families in Nottingham and across England receive extra support from their local councils from April this year.

A spokesperson for DWP said: “Benefits and pensions will also increase by 10.1 per cent in April, with the minimum wage seeing its largest ever cash rise, hitting £10.42 an hour. And more widely, the Energy Price Guarantee will save the typical household £500 in 2023/24.”

On April 1, the DWP will provide the extra cash via grants, with local authorities allocating the funds to atrisk families until the end of March 2024.

The initiative, launched in October 2021, saw ousted former Prime Minister Boris Johnson pledge to help families cover their living expenses in the early days of the cost-of-living crisis.

The scheme targeted areas with the most vulnerable households in the country.

To begin receiving money, applicants must contact their local authority, identified using the government website before ensuring the council is aware they are interested in the Household Support Fund – but authorities will decide who receives the cash, as eligibility criteria may vary.

Mims Davies, the minister for social mobility, youth, and progression at the DWP, said: “The Household Support Fund has already helped vulnerable families across England through these challenging times, and I am pleased it will continue to do so for another full year.

“This is just one part of our extensive and targeted £26 billion support package, which includes payments worth £900 for millions of people on benefits and additional support for disabled people and pensioners, whilst every household will continue to save money thanks to our Energy Price Guarantee.”