Thesis

Duncan of Jordanstone

of Art & Design

of Dundee

Fig.

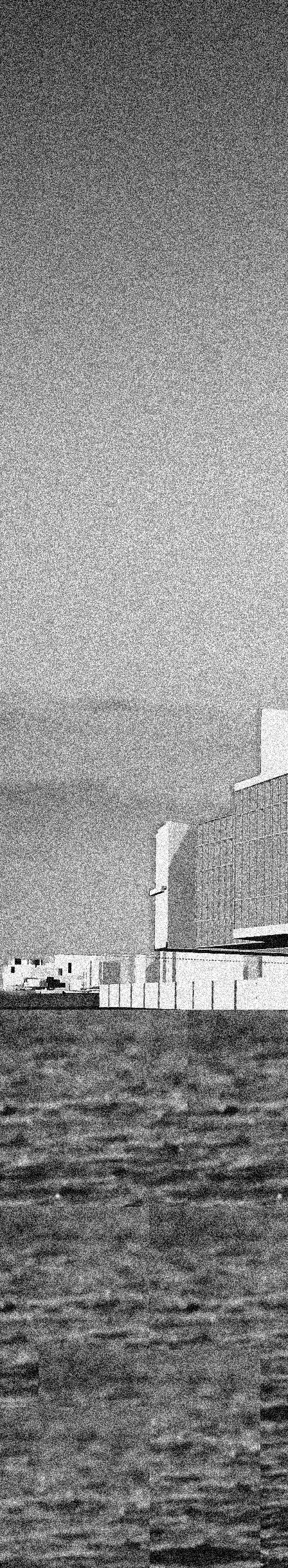

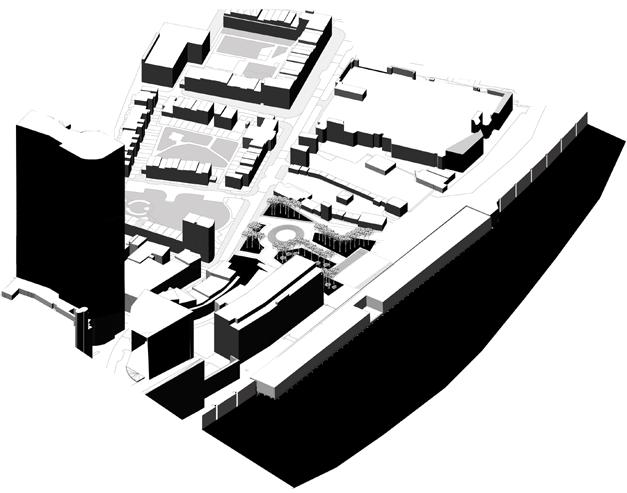

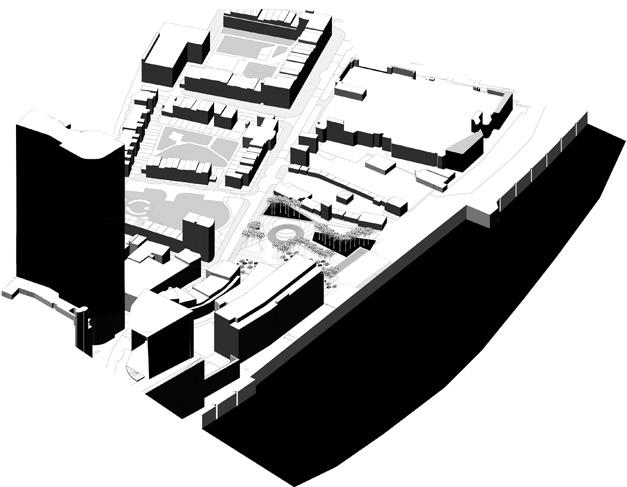

Bernie Spain Gardens waterfront

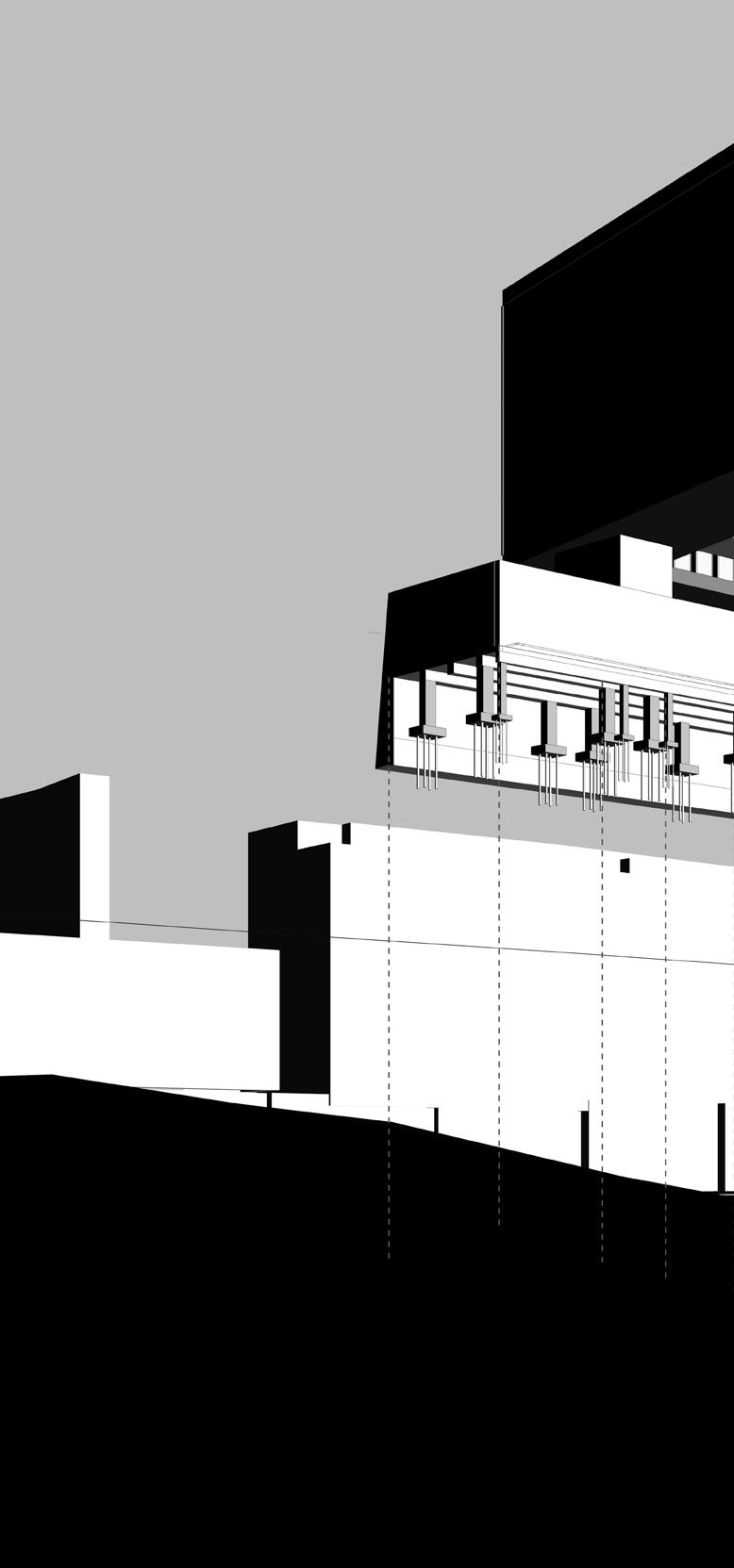

Fig. 01 Partial view of the [re]public from The Thames.

Fig. 01 Partial view of the [re]public from The Thames.

Duncan of Jordanstone

of Art & Design

of Dundee

Fig.

Bernie Spain Gardens waterfront

Fig. 01 Partial view of the [re]public from The Thames.

Fig. 01 Partial view of the [re]public from The Thames.

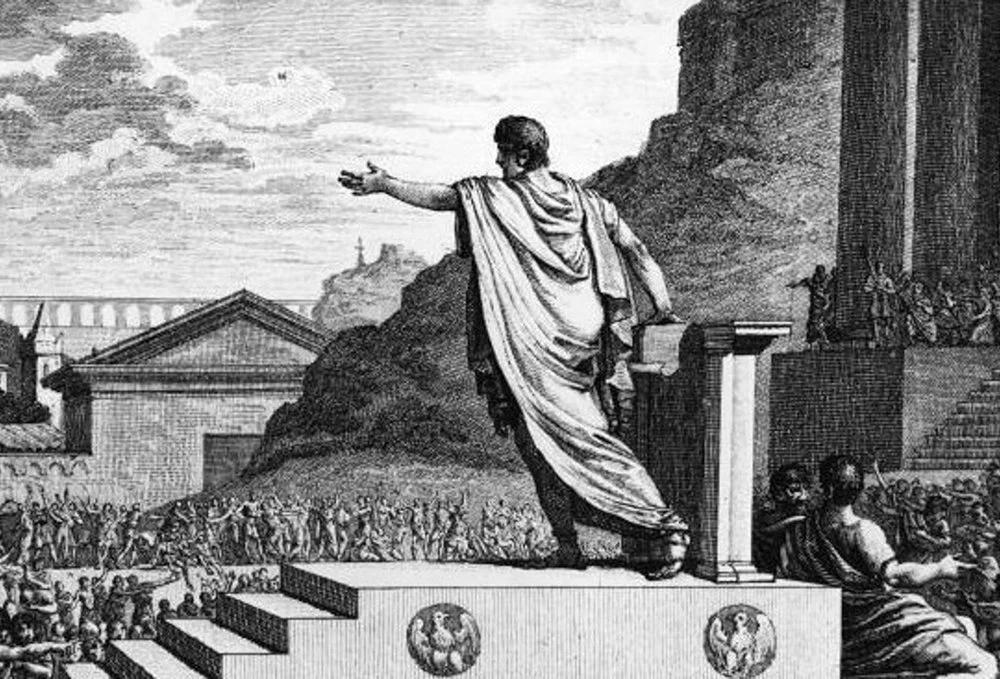

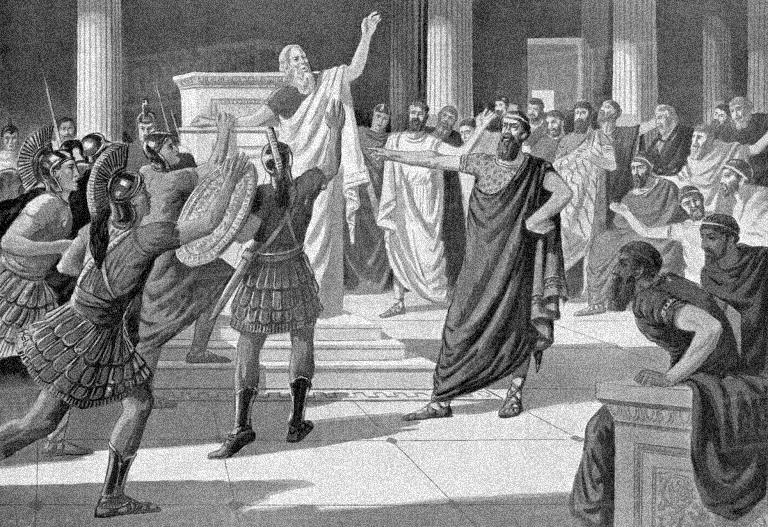

Fig. 02 Gaius Gracchus attempted to enact social reform in Ancient Rome, dying at the hands of the Roman Empire.

Fig. 02 Gaius Gracchus attempted to enact social reform in Ancient Rome, dying at the hands of the Roman Empire.

from Latin respublica, from res ‘entity, concern’ + publicus ‘of the people, public’

(1): a government in which supreme power resides in a body of citizens entitled to vote and is exercised by elected officers and representatives responsible to them and governing according to law

(2) : a body of persons freely engaged in a specified activity

Fig. 03 Palace of Nations (Geneva) collage. Adapted from University of Columbia

SOCIAL DRAMATURGY AS AGONISTIC POLITICS

PROLOGUE

PLAYS OF THE ‘POLITICAL ANIMAL’ THEATRE : THE ORIGINAL GOVERNANCE BODY OF THE GREEK POLIS

THEATRE: MAKER OF THE POLIS IT WAS DECIDED BY THE PEOPLE

ARCHITECTURE AS POLITICAL RITUAL: FROM THE BLUE SKIES OF ATHENS TO THE DARK ROOMS OF WESTMINSTER

THEATRE: A NEOLIBERAL TOOL

THE CHANDIGARH CAPITOL SOUTH BANK, LONDON: A REPOSITORY FOR THE [RE]PUBLIC

URBAN PLAY: AGONISTIC POLITICS DIRECT DEMOCRACY AS PROGRAMME CONCLUSION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

38 40

22 24 30 35 46 50

Origin // late 19th century: originally used in theatre to denote a short opening piece performed before a play. (Merriam-Webster)

public space, has now disintegrated. In turn, a fragmented capital-driven urban material made its way into the city, perpetually threatening public space. The construction of the Southbank Centre in the years immediately after WWII came out of a desire to offer a non-elitist national programme for theatre, embedded in the spirit of future-orientated spectacle and celebration of the 1951 Festival of Britain. Yet, after such a prodigious beginning, today, the Centre stands solitary amongst neoliberal objects, as an artefact reminiscing of this long-forgotten era.

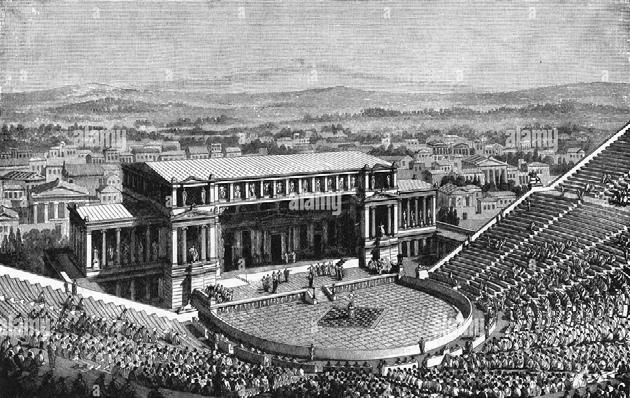

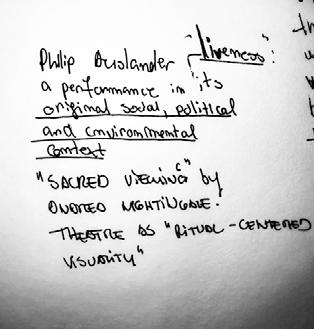

In 500 BC, the Athenian landscape saw the creation of a powerful democratic device: the theatre. Although initially believed to be a mere artistic spectacle, the origins and sophistication of theatre as social programme can be traced back to the very first forms of the archaic Greek polis (Wilson, 2007). Constructing a highly intricate mechanism, it challenged and warped issues of social identity, political views and religious beliefs (Winkler and Zeitlin, 1990).

In 2022, theatre is rather a mirror into a purely phantasmagorical world. Contemporary theatre plays transpose spectators outside of real life, as a means of escape from ‘social dysfunctions’ (Malzacher, 2015:13), as opposed to ancient Greece’s participatory and political character. Nowhere is this social paradox more evident than in the UK’s capital city, London. The collective welfare ideology at the core of post-War Britain, seeing the re-construction and re-definition of

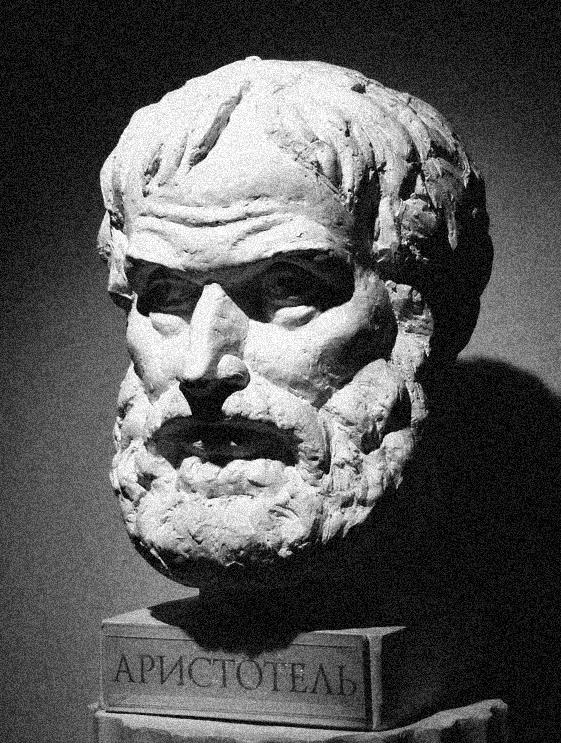

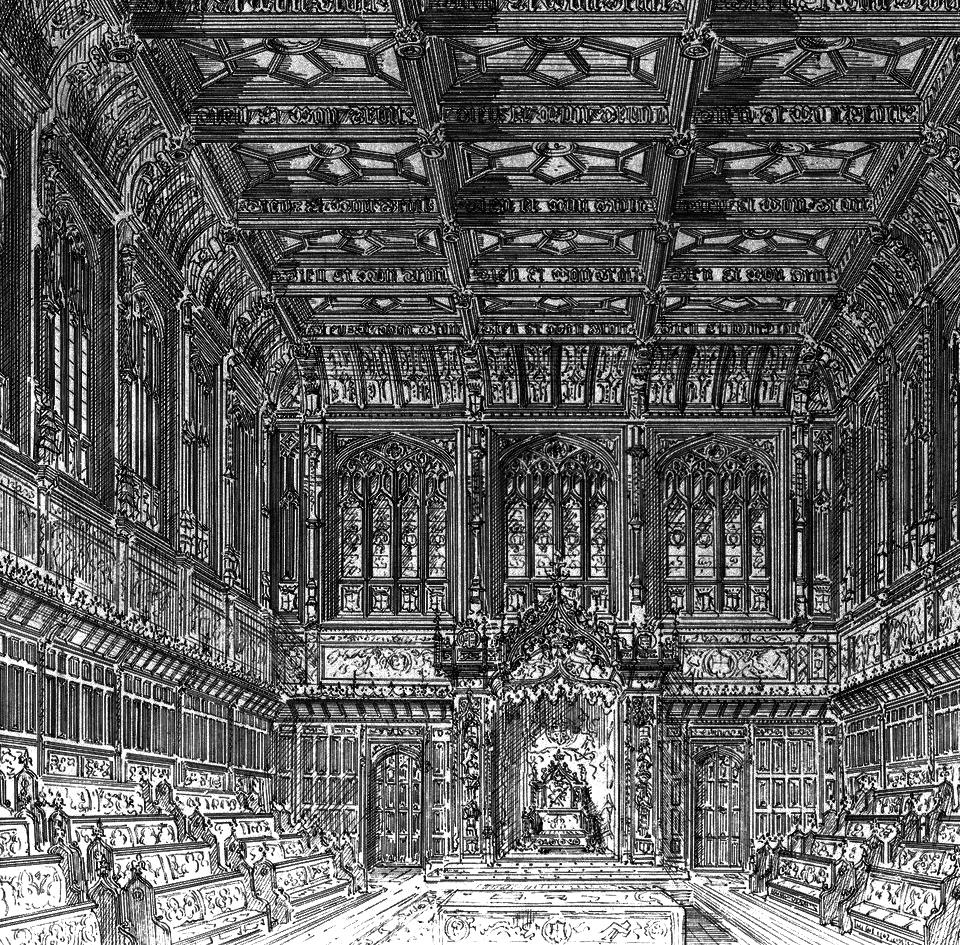

The very heart of what was once theatre –social identity– has today moved behind the closed doors of bureaucracy, dismantling the original relationship between politics, theatre, and space. Perhaps the most apparent instance of this is displayed in The Palace of Westminster, where political debate is played as a lengthy dramaturgical event surmounted by a myriad of rituals. What once emerged as a means of mediating and navigating the political life of the polis, today has become a spectacle in a world of Aristotle’s oligoi - the wealthy few.

Fig. 05 Debate in the House of Commons.

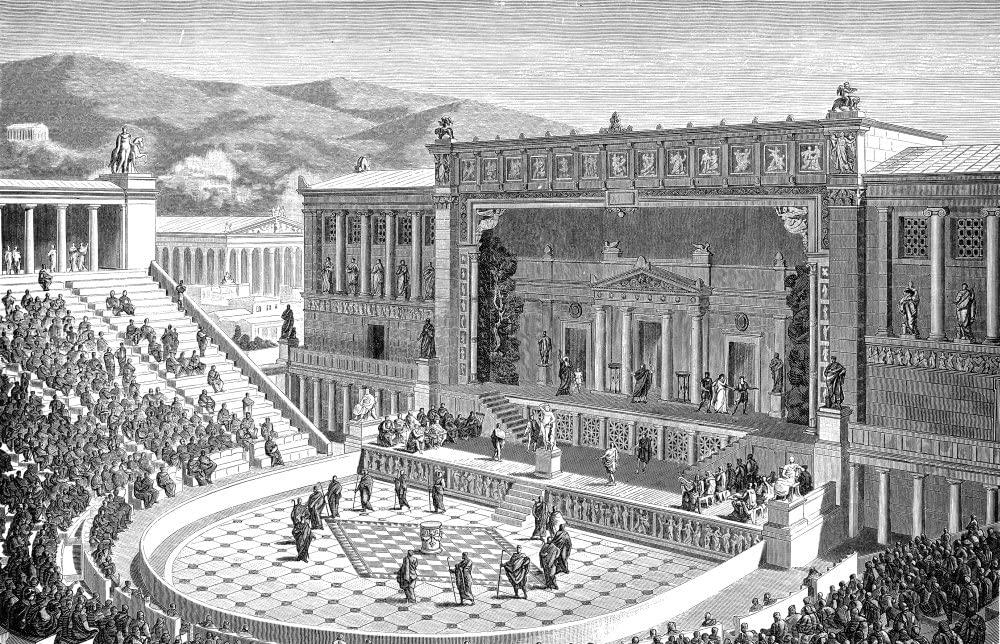

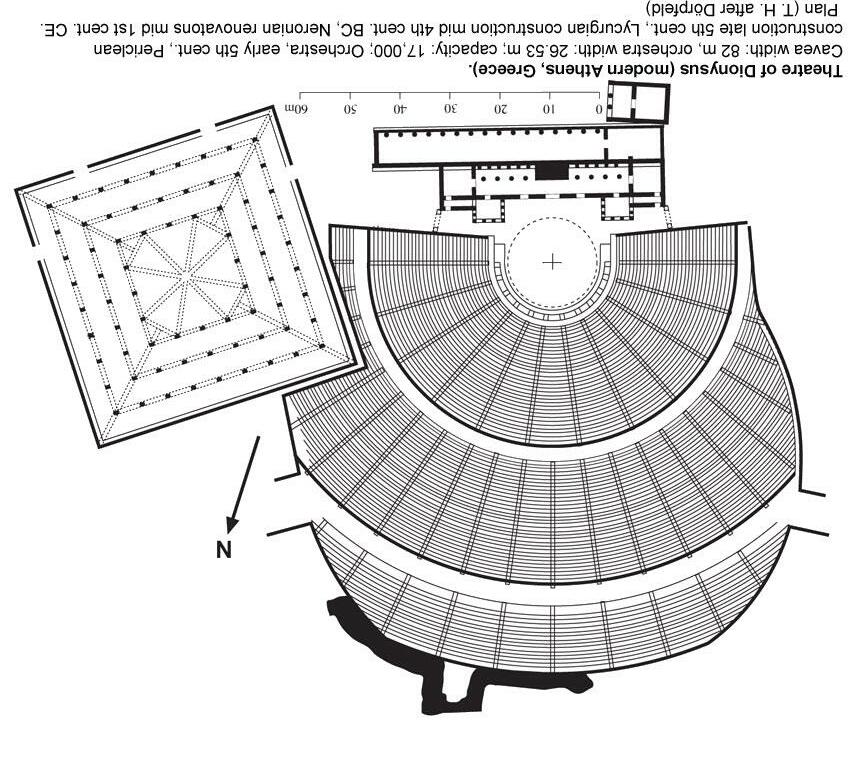

Fig. 04 Theatre of Dionysus, cca. 500 BC

Fig. 05 Debate in the House of Commons.

Fig. 04 Theatre of Dionysus, cca. 500 BC

Recent political theory has seen a focus on repositioning the individual within the current determinate political and social climate. The work of political theorist Hannah Arendt has been recently revisited in the scope of redefining democracy and the individual’s role in it. Both Arendt and political theorist Iris Marion Young (2011) agree upon the importance of individual and collective responsibility in creating a postoligarchic pluralistic society. However, theorist Chantal Mouffe sustains that it is only by creating ‘agonistic spaces of conflict’ that an alternate democratic environment can be established (Mouffe 2013).

This thesis aims to explore the means through which a spatio-typological intervention can reclaim the original relationship between politics, space, and theatre as political entity, situating itself adjacent to The National Theatre. The [re]Public explores theatre as democratic space, imagining a new theatre typology on London’s South bank. The new promenade stages dramaturgical politics, by placing debate back into the public realm and formally spatialising the process of direct democracy.

Fig. 06 The National Theatre, photographed after its opening in 1971.

Fig. 06 The National Theatre, photographed after its opening in 1971.

“[The National Theatre must] break away, completely and unequivocally, from the ideals… of the profit-making stage… It must bulk large in the social and intellectual life of London… be visibly and unmistakably a popular institution.”

– William Archer & Harley Granville Barker, 1904.

For Aristotle, the concept of politics referred to matters concerning the polis, rather than our contemporary understanding of the word. Furthermore, he identified the polis as the only system that can offer prosperity to man and defined humankind as a “political animal” (Cartledge, 2012:15), as man and society flourish through political systems.

The salient principles behind the emergence of the Greek polis and its bodies of governance relied on the heart of society, namely the citizen and most importantly, the many – as Aristotle referred to the masses forming a community (Cartledge, 2018). However, I would argue a deeper level of understanding in the formation of the city-state, as political entity, is provided by theatre. From as far back as archaic times, written plays held a strong political character, directly influencing democracy. It is therefore critical, that this thesis begins its exploration by studying what processes were engaged in the theatre machine and how these operated within the direct Greek democracy.

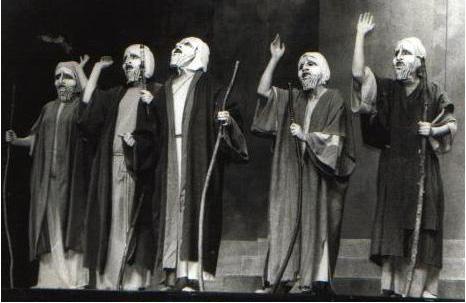

Dramaturgy’s trajectory in Ancient Greece is inherently tied to notions of ritual, symbols, and structures. Although research into theatre genesis widely takes the form of theoretical hypotheses, there is reason to believe that in fact theatre had its incipience in the rural agora. Archaeological accounts of the presence of a wooden stage in the agora on which citizens would freely hold community discussions have been made (Winkler and Zeitlin, 1990). These would have been the first spatialised forms of what later became a played theatrical spectacle. Theatre played a myriad of social roles within the Greek direct democracy. Whilst some involved challenging the citizen’s mindset or performing religious rituals, others focused on sophisticated political and warfare manipulation.

The stage was a place of mediation and agonistic dispute – a place of voicing one’s opinion, rather than a space for choreographed play. The political importance theatre held within the city-state was officially recognised by the governing powers in 500 BC, when it became an institution and was spatialised under The Theatre of Dionysus. Here, dramaturgy gained a mediated character, whereby the plays were used as political propaganda. It could be argued that despite this, theatre maintained a strong democratic spirit. The participatory nature shown in the early plays transformed into a more robust and orchestrated system, where a delegated group – the chorus, was placed on stage and whose sole purpose was to react to the play on behalf of the citizens. The public in this new setting, became a ‘quasiofficial political gathering’ (Winkler and Zeitlin, 1990:22), reinforcing the true political character of the play.

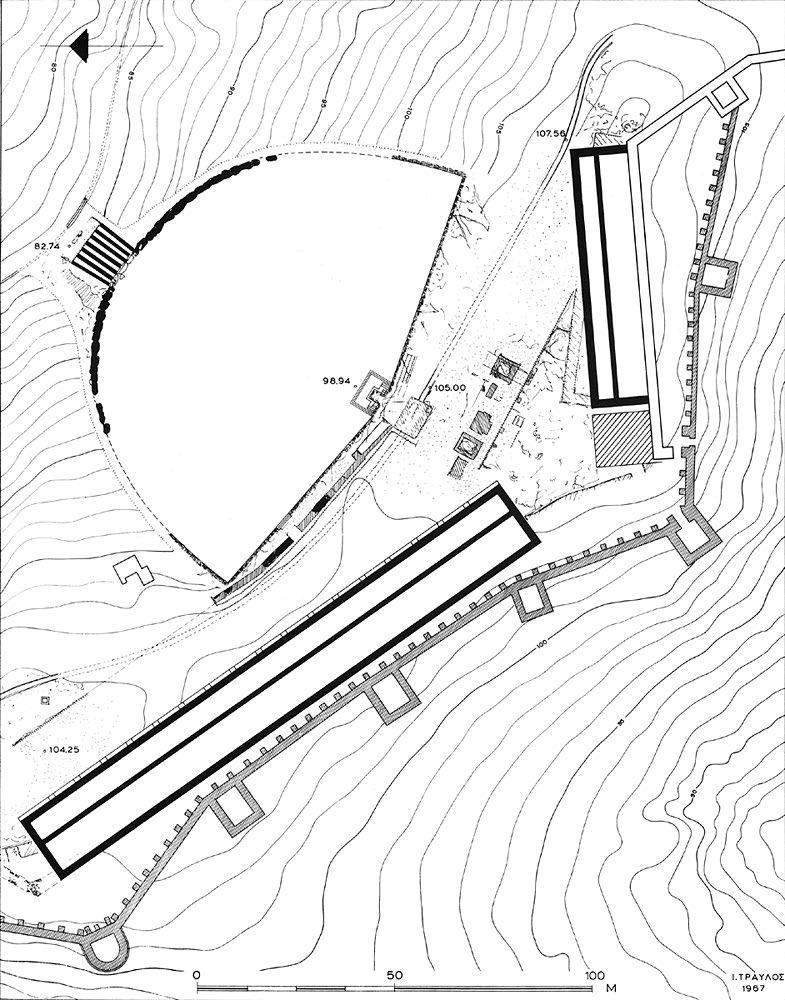

Fig. 08 The Acropolys in Athens with Theatre of Dionysus set within the hill.

Fig. 09 Greek chorus.

Fig. 08 The Acropolys in Athens with Theatre of Dionysus set within the hill.

Fig. 09 Greek chorus.

The highly orchestrated events held in The Theatre became an artistic extension of the political arm of the polis. Not only were they used as a connecting medium between the masses and the leading powers, but the protagonists became mediators themselves.

In the following chapters, this thesis will look at how politics was shaped by theatre, and how, today, this process has dramatically changed. Arguing that, the theatre has been divided into a commodity and bureaucratic debate, respectively. The thesis will look at The Palace of Westminster, as means to study the former, and at The National Theatre, to understand the socio-political reasons behind the latter. The exploratory project of the [re]public will then unfold based on a logic drawn from these.

Fig. 10 [own] collage study on the meaning of theatre as expressed by specialist literature

polis

n. /pɒlɪs/

Late 18th century borrowed from the Greek ‘polis’: citadel, city, community of citizens, city-state Corporation of citizens who all participated in its government, religious cults, defence, and economic welfare and who obeyed its sacred and customary laws (Merriam-Webster)

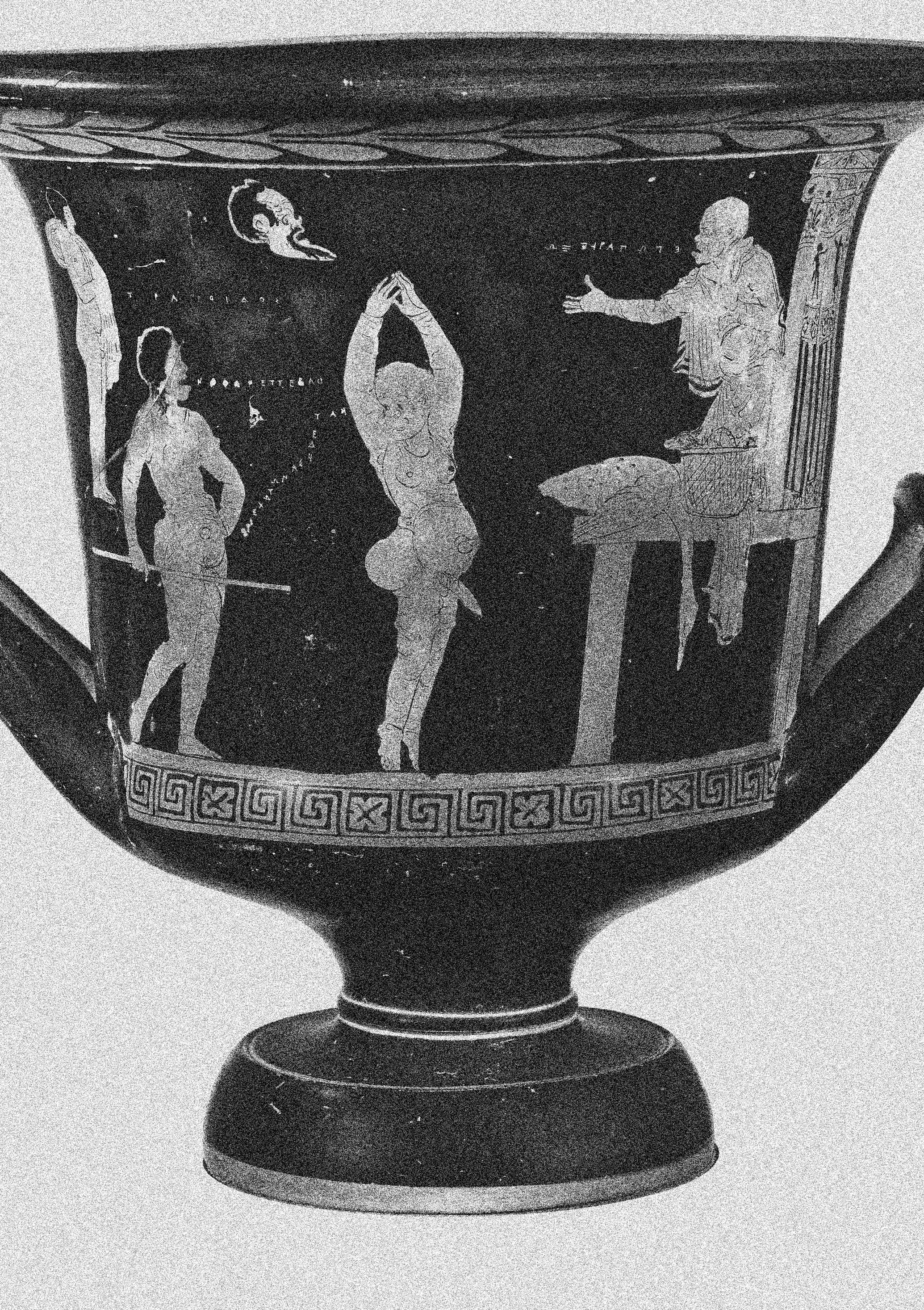

Fig. 11 Terracotta calyx-krater (mixing bowl) ca. 400–390 B.C. depictinga a scene from a Greek drama play. Adapted from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In the landscape of Athens, democracy was direct and participatory. Not only did theatre constitute a political device, but this was directly reflected in the architecture. It is no coincidence that the Pnyx, a stone amphitheatre used for popular assembly and the Theatre of Dionysus, were built in the same character: open-air stonecarved auditoria. In fact, not only were they organically set within the landscape, but they were also inviting. This was a way of spatialising the polis’ direct democracy: free, inviting, and uncontrolled.

Over and above this, the pivotal element displayed by theatre was the play structure. This sophisticated morally manipulative device initially started by re-enacting daily social occurrences, played by the community members. Allowing conflict to arise, fostered what contemporary political theorist Chantal Mouffe termed an ‘agonistic debate’ (Mouffe, 2013: 12) landscape.

Theatre was by no means a way in which citizens were expected to reach a consensus, but a modus operandi whereby the values of democracy were set forth. Freedom of speech, the right to have a conflict with an individual from a different social class, and ultimately, the right to belong to a community, were all values conveyed by theatre.

Fig. 12 Matrix :Theatre of Dionysus (top) and The Pnyx (bottom). Both share identical layouts,.

Theatre & Pnyx

Theatre & Pnyx

[...] for an analysis of Athenian society, the study of political rhetoric and drama must go hand in hand, and the ideological background revealed by political rhetoric will elucidate the meaning of dramatic texts.

– Winkler and Zeitlin, 1990: 240

The very first Greek law was the one of Dreros, concerned with regulating the position of power individuals would hold within a community. Crucially, this represented stance people (the demos from demokratia) took on anti-tyranny: an opposition to any form of governance that involved power given to the few. The few were characterised by wealth, making them by definition ‘oligoi’ – term from which contemporary oligarchy stemmed (Cartledge, 2018).

discomfort and unease, which eventually forces individuals to change their behaviour, state of mind or feelings. Scientifically, the act of dissonance is proved to be an effective medium for better decision-making and empathetic resonance (Meineck, 2018).

Drama plays, therefore, created an ideal subconscious storm. Philologist John Winkler, in his work on political theatre and the Ancient Greek polis, argues that this was a critical part of the institution of dramaturgy, which intended to ‘heighten the audience’s consciousness of its social integration’ (1990:19). Challenging the citizens’ political views, the theatre became an ideal political and psychological mechanism.

Dramaturgy, as a decision-making infrastructure, began losing its character in time, with theatre appropriation for political gain becoming more apparent in the Hellenistic era. Politics, as played in Athens’s Law Court was unequivocally theatrical.

‘Critias, one of the Thirty Tyrants, ordering the execution of Theramenes, a fellow member of the oligarchy that ruled Athens in 404–403 BCE’

The mechanism used to resolve political conflict through social dramaturgy, and more specifically through drama plays, seems straightforward. It is only when dissecting it that its psychologically intricate mechanism unfolds. The plays worked on different psychological levels, starting from making the citizen self-identify with the hero, and at its most effective, entering the realm of neuroaesthetics and cognitive dissonance. This holds strong psychological effects, creating feelings of

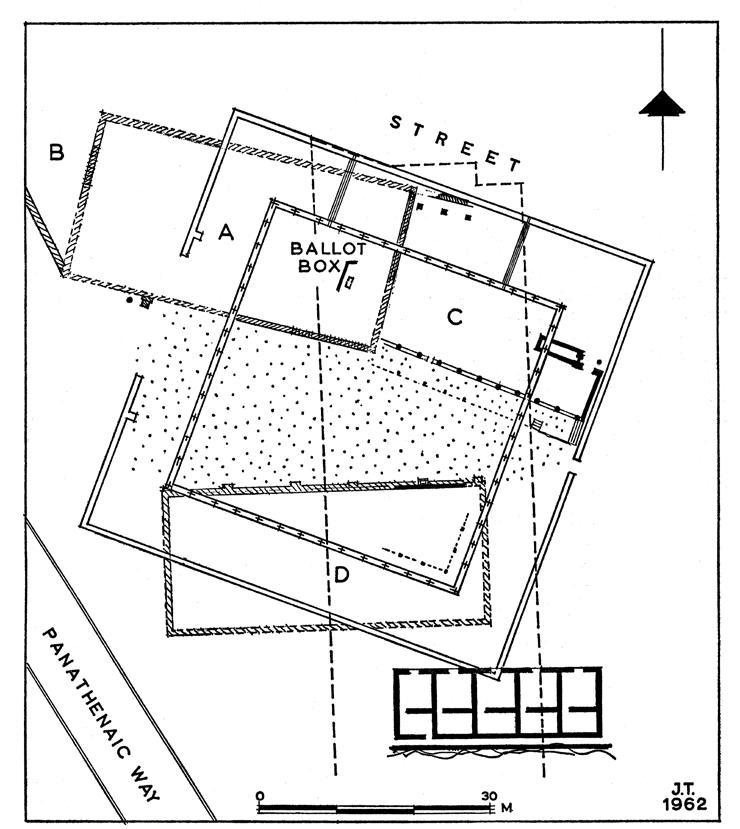

Fig. 14 Early Law Court buildings in the agora. Extract from Thompson and Wycherley, 1972:p.58

Fig. 13 Thirty Tyrants

Fig. 13 Thirty Tyrants

It could be argued, in the context of this thesis that this is where theatre diverted from being a democratic device of the many to be a bureaucratic system of the oligoi. The notion of actors became a notion of politicians engaged in a speech-giving mission that met no ethical limits (Meineck, 2018). Subsequently, this would make The Law Court an archaic version of contemporary political debate: a theatrical act played out for an entertainment-insatiable public.

The original ‘cognitive dissonance’ method was re-purposed to build a society where democracy, as known in archaic times, was entertaining and provocative, rather than participatory and direct. This today, can be observed in the case study this thesis puts forward- The Palace of Westminster.

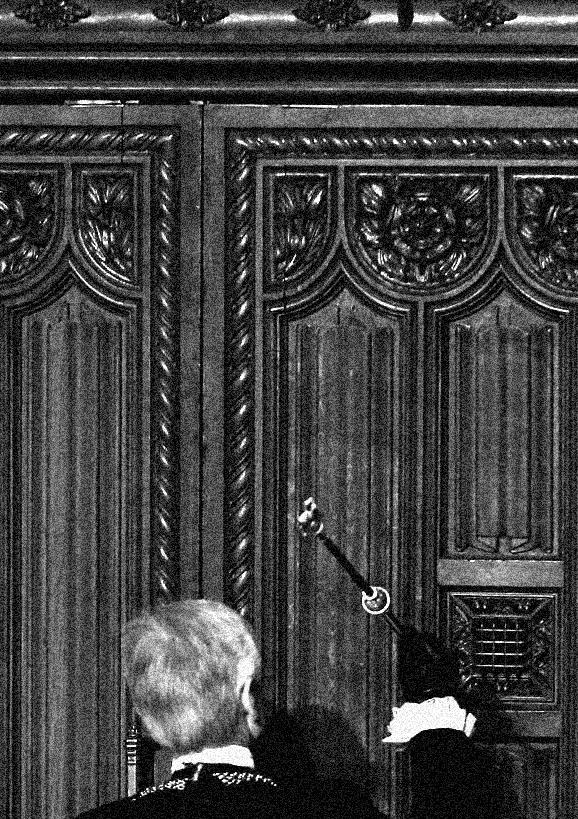

Fig. 15 The Black Rod Ritual, Palace of Westminster.

The Black Rod knocks on the Parliament door to symbolise the Commons’ independence from the sovereign.

Fig. 16 The Black Rod Ritual, Palace of Westminster.

When the King is seated, either he or my Lord Great Chamberlain gives you Order to call the House of Commons. Then you go immediately, and when you come there, you knock with the end of your rod four or five times, and when the Doors are open, [you] come in as high as the bar, you make a Congee [bow], and then going three steps further another, and then advancing further another. And then holding up your Black Rod in your hand you say Mr Speaker, The King commands this Honourable House to Attend him immediately in the House of Peers. Then you go out making your Three legs [i.e., bows]. And stay for the Speaker in the Painted Chamber and going in, and standing at his Right hand, [...]you make three Congees and go and stand with him at the Bar holding your Black Rod in your hand.

Earliest description of the Black Rod ritual. Extract from Sir Thomas Duppa’s Notebook, 14 August 1679.

Aristotle, who was a great believer in Athenian democracy, argued that the theatrical nature of the Law Court offered the ‘most scope for trickery’. Here, politics gained a ritualistic and well-rehearsed nature, with the sole purpose of individual political gain.

referred to as consumers, is constantly made. In today’s political realm, theatre, the maker of the polis, does not exist anymore.

Being part of the political sphere in Ancient Greece was a right. With no voting systems, any citizen was allowed and even encouraged to speak up in the Assemblies and represent their community (Cartledge, 2018). In complete opposition to this, democracy today is solely based on the highly mediated system of voting. The many, as described by Aristotle, are today reliant on the few to help shape their communities. One of the key spaces where this paradox can be studied is The Palace of Westminster. Here, The House of Commons, one of the most televised debate rooms in the world, engages a myriad of anachronistic politics-forming rituals. Dragging Mr Speaker into the chambers following their appointment, the slamming of the hyper-sized door in the Black Rod’s face or the MPs’ division into the ‘Aye or No’ lobbies (House of Commons Information Office, 2010), The House displays an ample political set-piece. Here, politics is heavily reliant on these rituals throughout the democratic process. The most fundamental element of the rhetoric played in The House of Commons – speeches – are not only written before the assembly gathering, but also partly disclosed to the opponents. By eliminating direct public participation, it can be argued that politics is hereby played, rather than conducted.

What Arendt calls ‘agonal spirit’ (Arendt, 1958:194)- the drive to stand for one self’s own identity in front of others was the cornerstone of the Ancient Greece city-state society. Unencumbered and free, the citizens of the polis were able to make decisions informed by dramaturgical plays. This social construct has now diminished, both within the public and political debate realms. The initial relationship between space, theatre and politics that stood at the core of the polis, has now been dismantled by the rise of neoliberalism and the unquenchable hunger of the capitalist world. The clear delineation between politics (decision-making) and the citizens, who are now

Architecture as political ritual: from the blue skies of Athens to the dark rooms of WestminsterFig. 17 Entrance to the House of Commons Fig. 18 The House of Commons

Fig. 19 Mass Diagram of The Palace of Westminster. The administrative blocks form part of the facade, concealing the politics behind. This stands as demonstration that architecture plays an essential role in placing political debate behind the closed doors of bureaucracy. The revealing elements are the towers, which bring a certain degree of natural light in. All courtyards are internal, bordering the Houses.

House of Commons Aye Lobby No Lobby

House of Commons Aye Lobby No Lobby

As the architecture of amphitheatres in Ancient Greece directly mirrored their political character, so is the architecture of The Palace of Westminster, reflecting its political processes. The ritualistic nature of its spaces, with its elongated lobbies, facing opponents in the Chamber, and dozens of hidden offices behind its imposing façade, plays an essential part in successfully conducting the ritual, thus transforming it all into a closed performance of the few. With an imposing presence, the building almost looks inwards- all courtyards and hallways being concealed from the urban presence. Each element of the building allows and encourages the ‘cut-and-thrust debate style’ (House of Commons Information Office, 2010: 4), the House of Commons engages in. Interestingly, the Chambers’ position at the core of the building is somewhat contradictory to the Parliament’s ritualistic nature. Although centrally located, both Chambers are isolated from other facilities, which strengthens the argument that democracy here is not a matter of the many. The visitors’ gallery, while allowing the public to observe debates, is not integral to the Chamber’s layout. Placed on a raised platform, the gallery acts as a passive viewing platform. With no means of actively participating in the debates, the public virtually watches a political play.

While stone in Ancient Greece was used to create almost invisible theatre settings, with structure disappearing into hills, limestone was used in The Palace’s construction as it allowed for highly intricate detailing (UK Parliament, n.d.). For the latter, the highly detailed façade masks The Palace’s urban presence, while simultaneously imposing it onto its context with its 98.5 metres tall figure (UK Parliament, n.d.). Perhaps a similar parallel can be drawn between the way politics is carried out within the Chambers, and the way it is portrayed to the public. Concealed, yet seemingly revealing, the ritualistic plays found here mirror a non-direct and non-participatory democracy.

Fig. 20 Palace of Westminster

Fig. 20 Palace of Westminster

Art has been subsumed by the aesthetics of bio-political capitalism and autonomous production is no longer possible.

- Chantal MouffeThe governing tropes in the world of visual arts, rarely make space on stage for the political nature of the Greek performance. Without a sense of reality or debate, contemporary theatre has become a spatial subsumption of the current post-political era (Eckersall and Grehan, 2019).

Amongst the large-scale architectural ambitions, arising from a vision of collective welfare after WWII in London, was The Southbank Centre. In a celebratory act, the Centre was created as a grandiose move for the 1951 Festival of Britain, to populate the South bank with a multitude of non-elitist programmes. Nested within, was The National Theatre building, whose architect Denys Lasdun envisioned it as a true pluralistic landscape. However, this social progressivism movement, entrenched by the speed of the free market, launched the initial ambition for The National Theatre into a commodification downfall (Ferrone, 2021). The sharp ascend of mass culture in the last decades, facilitated the commodification of dramaturgy. Theatre plays have now become products consumed by a market-oriented society. Undoubtedly, this is a far cry from the active character theatre initially had. As it currently stands, The Palace of Westminster specialises in a ritualistic performance, whereas contemporary play transports its audience into a phantasmagorical world (Malzacher, 2015).

Neoliberalism has also greatly affected public space. In an insatiable hunt for profitable land, neoliberalism took over central London, ingraining glass trophies around The Southbank, and eventually drowning it (Harvey, 1975).

As political theorist Chantal Mouffe discusses, politics based on consensus are overarching components in today’s society. To create a paradigm shift, Mouffe argues that a modus operandi based on the agonistic debate is imperative. To address this and attempt to

spatialise it, the [re]public has to overturn the idea of passive democracy, as well as passive dramaturgy. Repositioning public debate into the dramaturgical landscape of London’s South Bank becomes the central task of this thesis.

To orchestrate the logic required for a strong urban scheme, the thesis turns to a very relevant example - The Chandigarh Capitol.

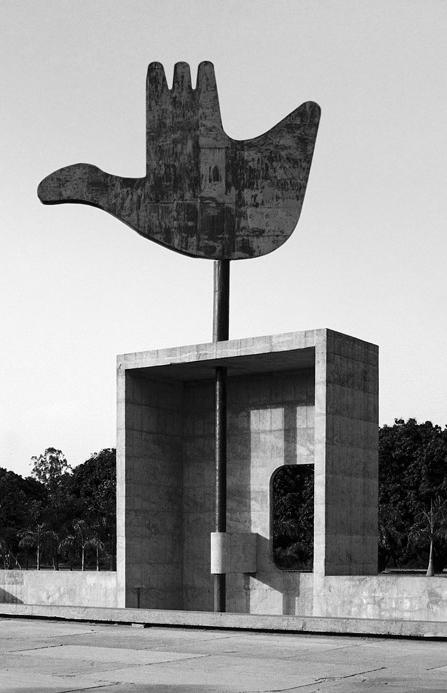

Fig. 21 The Open Hand Monument at Chandigarh, symbolising the unity and prosperity of mankind.

Agonistic public spaces provide the terrain where conflicting points of view are confronted without any possibility of a final reconciliation - Chantal Mouffe

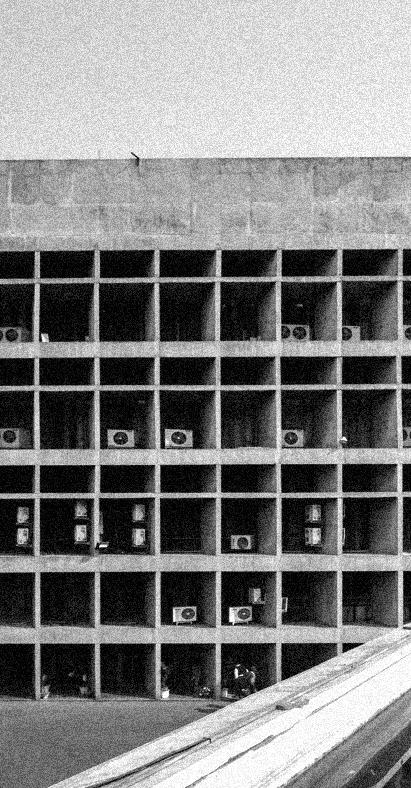

Fig. 22 Chandigarh’s Capitol - The Palace of Assembly

Repositioning the individual, as opposed to a mass-driven society, within a post-political indeterminate fabric, is paramount to achieving this. A relevant example which managed to use architecture as a tool for addressing democracy is the Le Corbusier’s City of Chandigarh. Here, politics forms the core of a large-scale urban master plan. The orchestration of Chandīgarh’s political components is akin to the socio-political revivification ideology behind The Southbank Centre. In both cases, the ambition was, largely, to generate spaces for a new society.

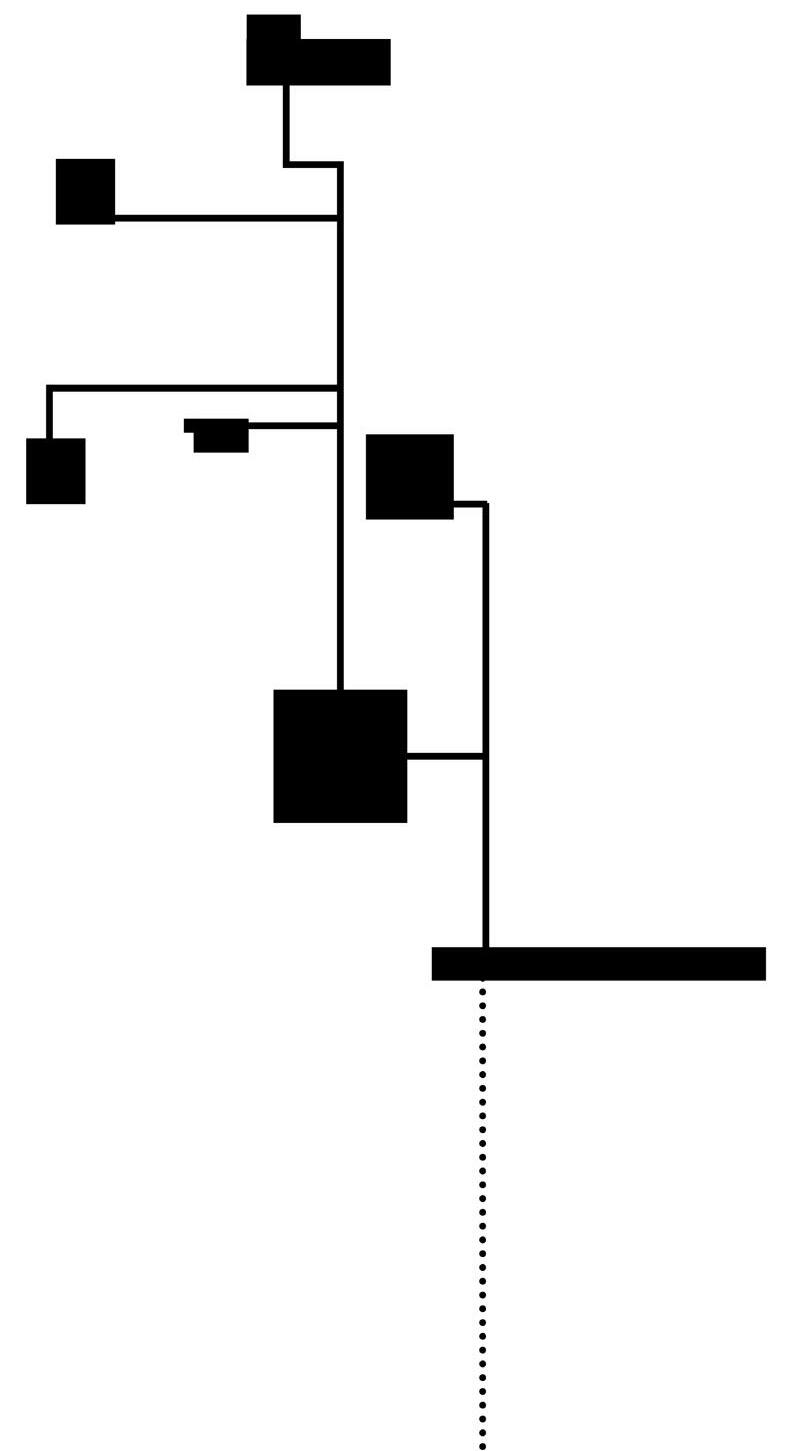

To design a nation’s identity, Le Corbusier divided power into three pillars: legislature, executive and judicial. This set the stage for creating a monumental master plan for the new capital. The new Punjabi capital has a multitude of programmes: from residential neighbourhoods to industrial areas. However, relevant to this thesis is how Chandigarh’s Capitol was formed.

The general scheme of the city of Chandigarh was nascent out of the literal idea of the human organism. While the industry was an arm, The Capitol was the ‘head’ of this larger urban orchestration (Bharne, 2011). The leading body of power sits detached from Chandigarh city, placed on a ‘monumental connecting axis’ (Bharne, 2011: 2), and almost acts as a fortress between the city and the neighbouring village. Undoubtedly, the clear relationship between the administrative, assembly, leadership, and public art areas of the Capitol renders it a political machine. The monumental concrete architecture of the Capitol Complex acts both as a landscape and carefully detailed small-scale spaces (Boesiger, 1995).

Fig. 24 Diagram of Chandigarh’s Capitol showing the urban linear axis it is placed on. Unlike The Palace of Westminster, Chandigarh is opening outwards, creating a building assembly.

Fig. 25 (opposite) Chandigarh’s Masterplan showing the ‘head’ and ‘arms’ of the scheme.

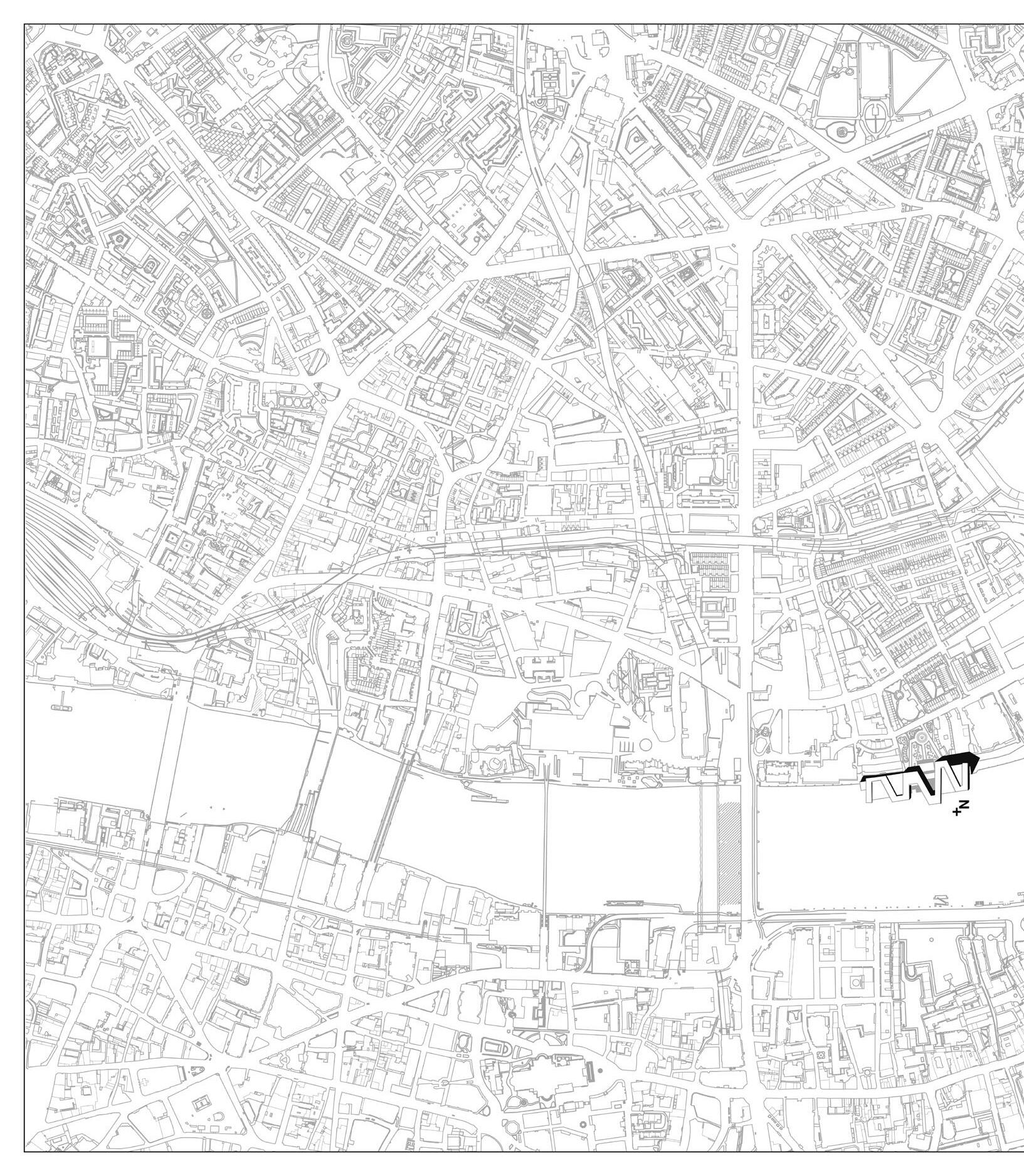

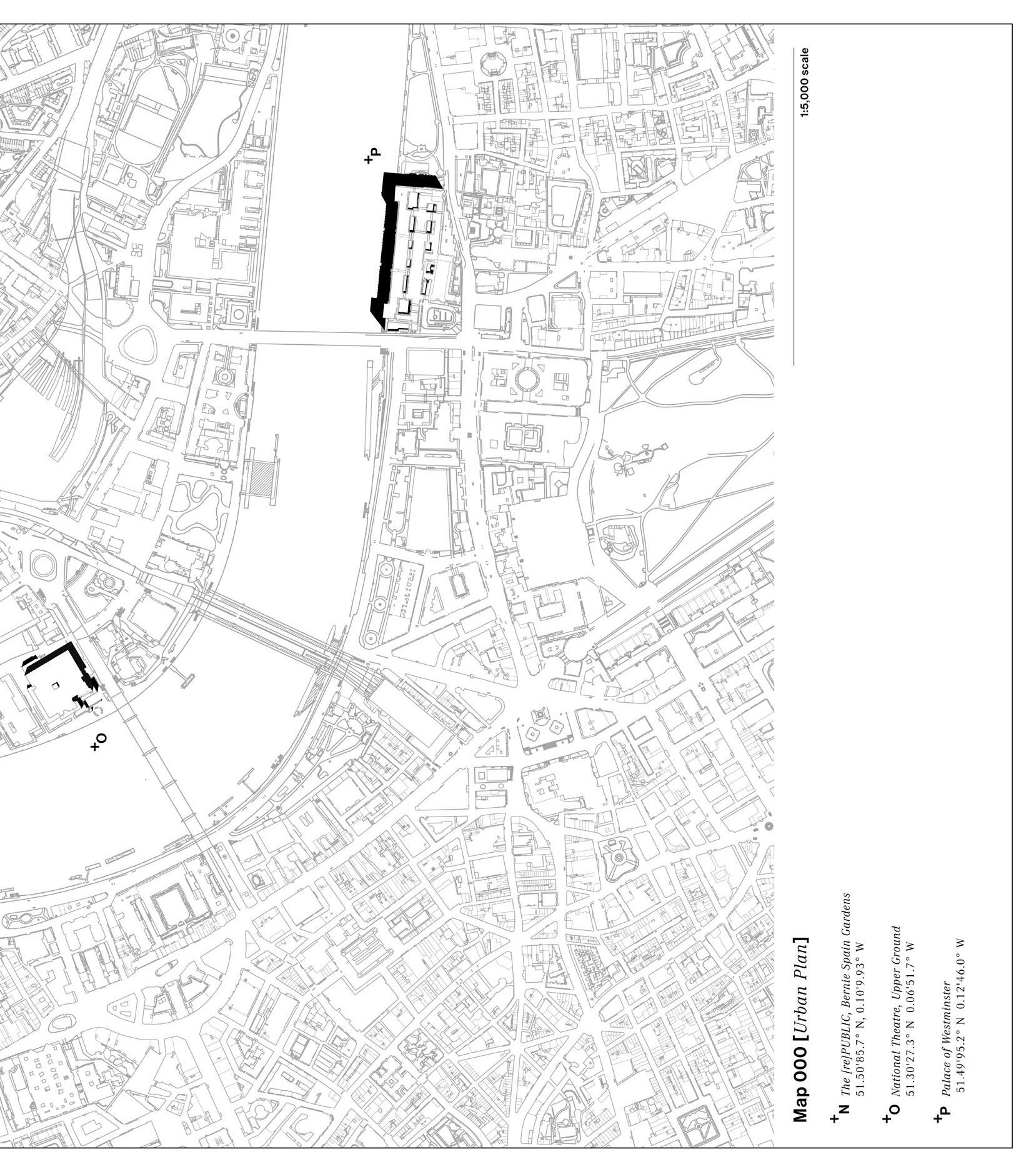

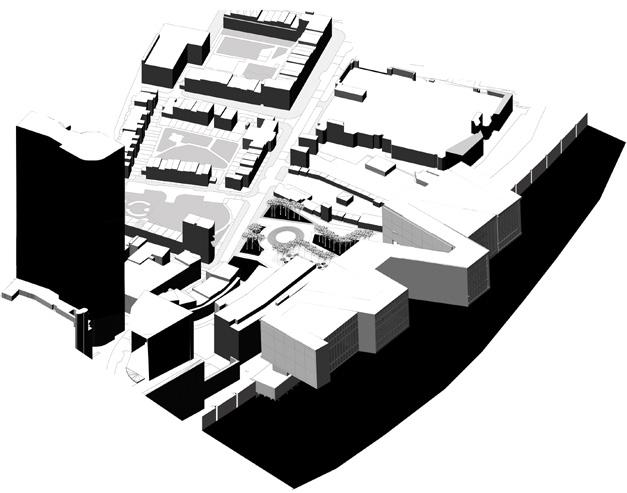

Positioned on the opposite Bank from The Palace of Westminster, London’s South bank strategically lends itself to house the [re] public. The geographical opposition between the North Bank and The South Bank translates into a dichotomy between bureaucracy (The Westminster Palace) and dramaturgy (The Southbank Centre). Choosing to specialise in the [re]public adjacent to The National Theatre, thus becomes a straightforward decision.

The architecture of the South bank, in particular the promenade on the edge of Bernie Spain Gardens, constitutes a lucrative area to start exploring in detail. The heavily socio-political background of the site is not to be overlooked. The Gardens were built as part of a collective mission to discourage a potential capitalist takeover. Bernie Spain, the lead activist behind this, mobilised a group of fellow activists and eventually managed to buy the land over and build affordable housing, as well as the Gardens (Coin, n.d.).

The exploration, therefore, begins by re-defining the site’s water edge, in an attempt to start from an urban scale and work towards a microenvironment.

Fig. 26 Bernie Spain Gardens - The pier.

The National Theatre

Fig. 25 South/North Bank aerial view.

The Westminster Palace

Fig. 27 Thames Map

Fig. 26 Bernie Spain Gardens - The pier.

The National Theatre

Fig. 25 South/North Bank aerial view.

The Westminster Palace

Fig. 27 Thames Map

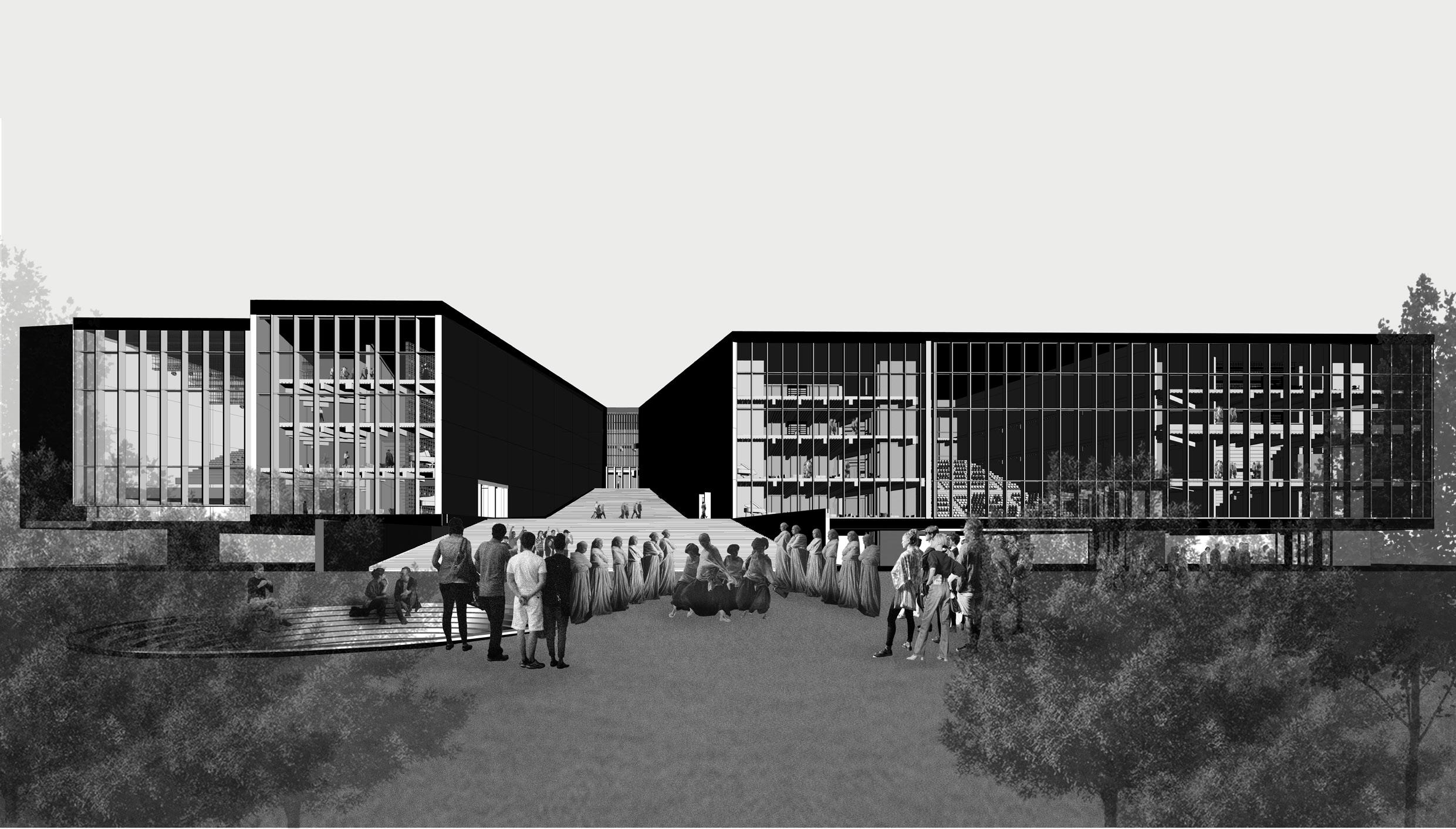

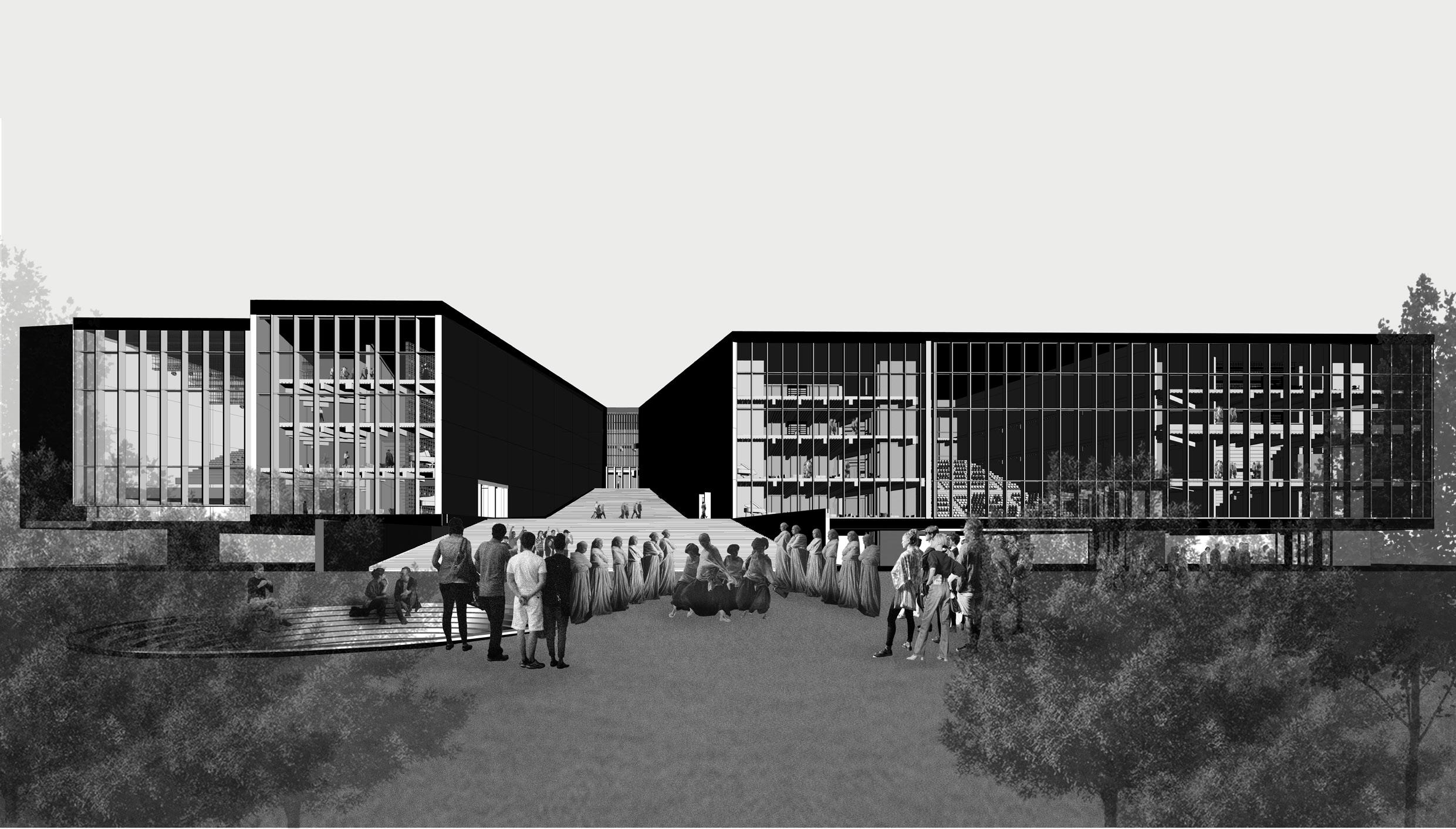

Fig. 28 View of the [re]public from the Thames.

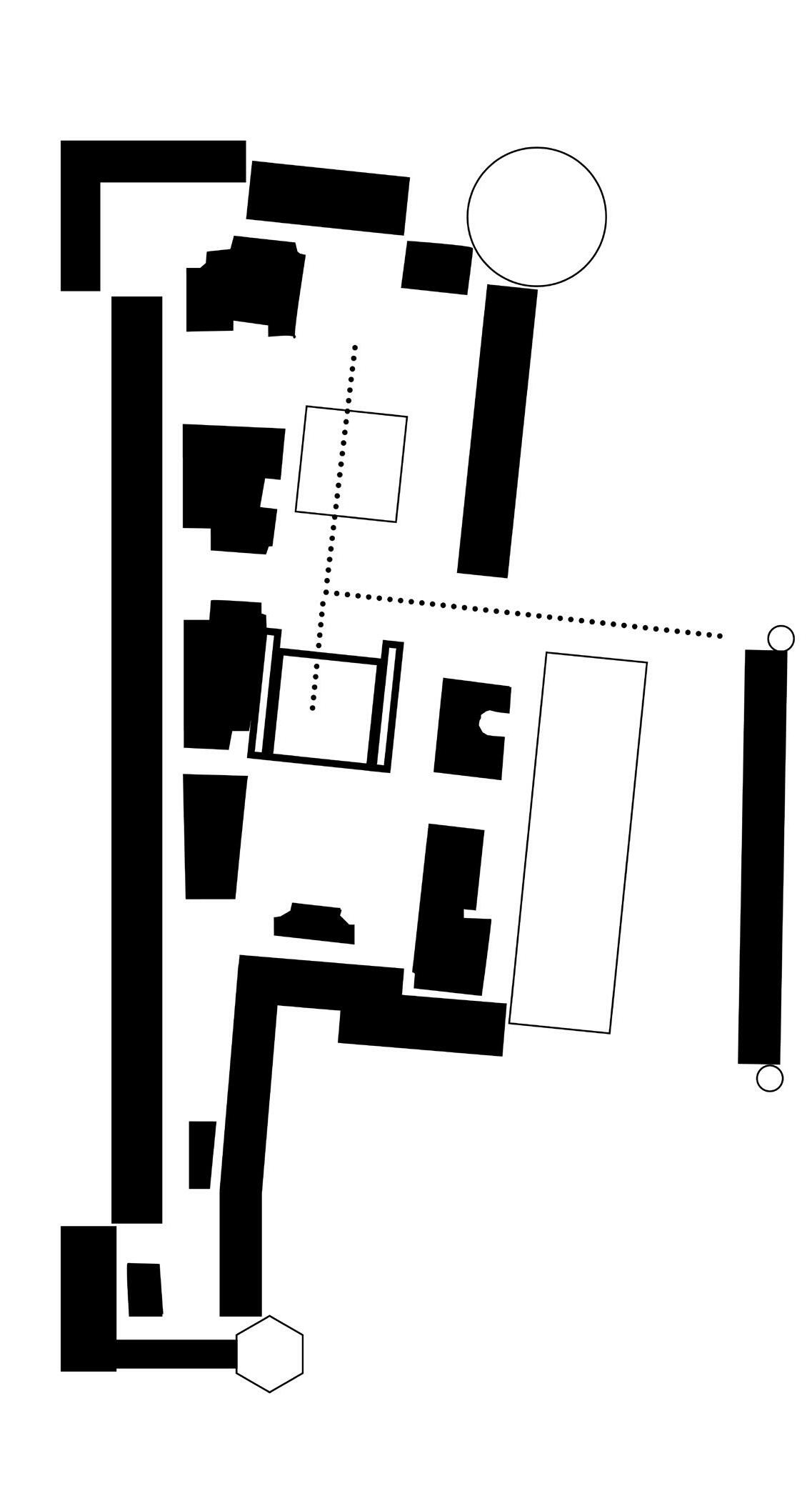

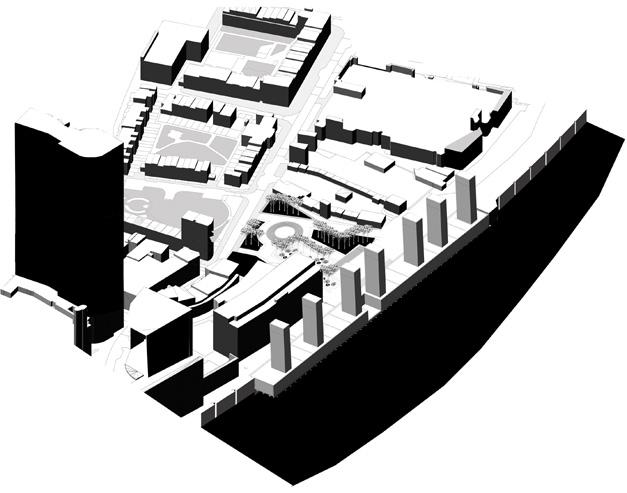

Fig. 29 Urban Plan [scale 1:5000 @A1)

In the city of unitary urbanism, however, urban dynamics would no longer be driven by capital and bureaucracy, but by participation.

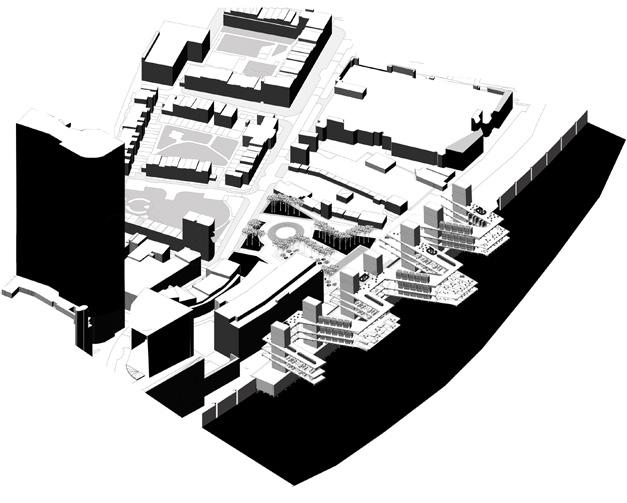

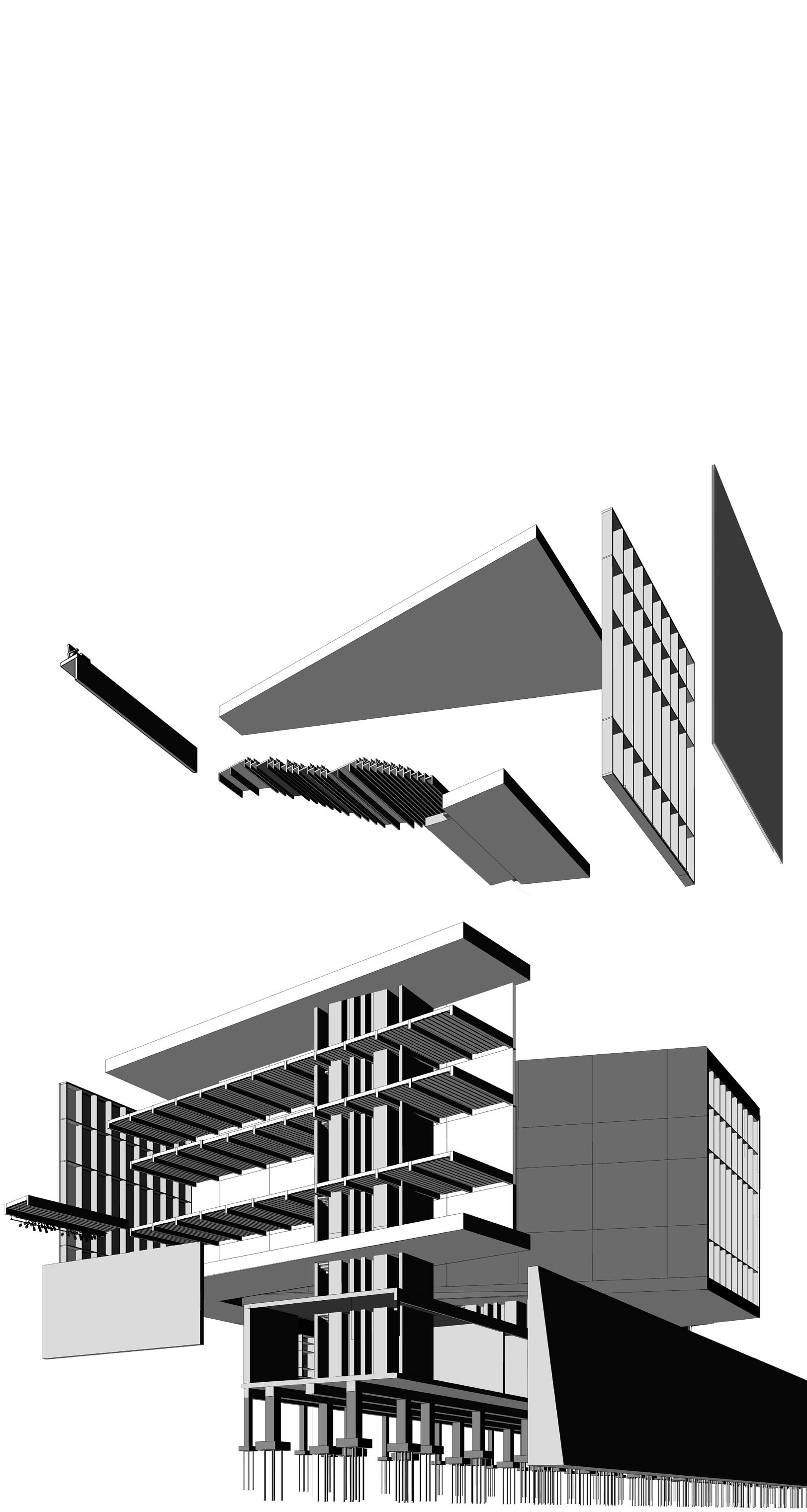

-The SituationistsPlaying between a macro and a micro scale is what the [re]Public exploration is progressing onto. For the [re]Public to begin to form a spatial proposition, Mouffe’s political landscape needs to first be produced as a programmatic matrix, using the ideology of democracy through spectacle. Centred around the theatre, the programme naturally begins by situating this at its core, both physically and conceptually. The next step within this logic is to recognise the importance of an administrative arm, that operates politics alongside the theatre. The first step in formally orchestrating the [re]public sees a transformation of the water’s edge. This comes as a reaction to the non-linear definition of the current pier. The bureaucratic annexe here comes into play, which, through its inherent nature, borrows a very linear form, and thus its roof doubles up as the new linear promenade. The administrative floor within gets pushed down into the riverbank, allowing high tides to almost submerging it at various times of the day. Subsequently, the irregularities of the site axis lend themselves to forming the theatre block. To retain the new promenade as a unidirectional path, the theatre gets pushed up, now being cantilevered by the circulation cores arising from the administrative block. The Bernie Spain Gardens is currently divided into two main park areas. To link the new promenade with the first portion of the park, a new landscape is formed, using the same site axis, and playing upon the newly formed cantilevered theatre volume.

1. The National Theatre

2. Gabriel’s Wharf

Bernie Spain Gardens

side)

30 Site Plan

Theatre Auditoria

Oxo Tower

Walls

Agonistic public spaces provide the terrain where conflicting points of view are confronted without any possibility of a final reconciliation

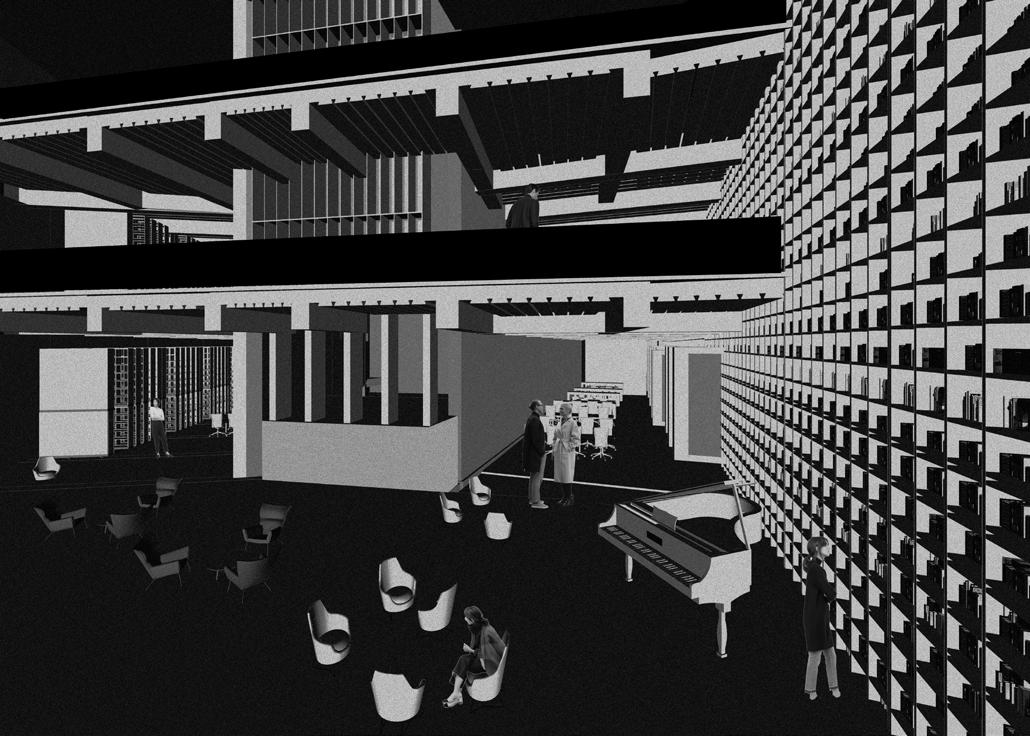

-Chantal MouffeTo define the theatre volume both in terms of the detailed programme and spatial qualities, it is imperative to understand what democracy means and how this can be spatialised. In principle, the process of democracy can be dissected into four divisions: research, knowledge, representation, and popular sovereignty (Diamond, 2004). In redefining these categories to frame the thesis ambition, popular sovereignty is represented by the theatre auditoria, which holds theatre plays and after-debates, thus starting to revive the political role theatre initially held in the polis. Further following the thesis’ ambition, the project divides the theatre volume into two formal parts: the walls and the spaces in-between these. The investigation plays upon the solidity of the wall, as a programmatic enclave, enclosing the auditoria between each set of walls. Expanding on the above analysis, the walls can then hold the four democratic stages: library and archives (knowledge), meeting floor (research), lobbying floor and gallery space (showcase). Finally, the overall programme can be divided into 3 main categories:

The (new) Promenade

The Walls

• Judicial library + archives (knowledge)

• Democratic floor (research)

• Lobbying (restaurant + bars)

• Exhibition (showcasing)

The Theatre Play + Debate Auditoria

Fig. 32 Overall Perspective- Water View

Each constructed situation would provide a decor and ambiance of such power that it would stimulate new sorts of behaviour, a glimpse into an improved future social life based upon human encounter and play

-The Situationists

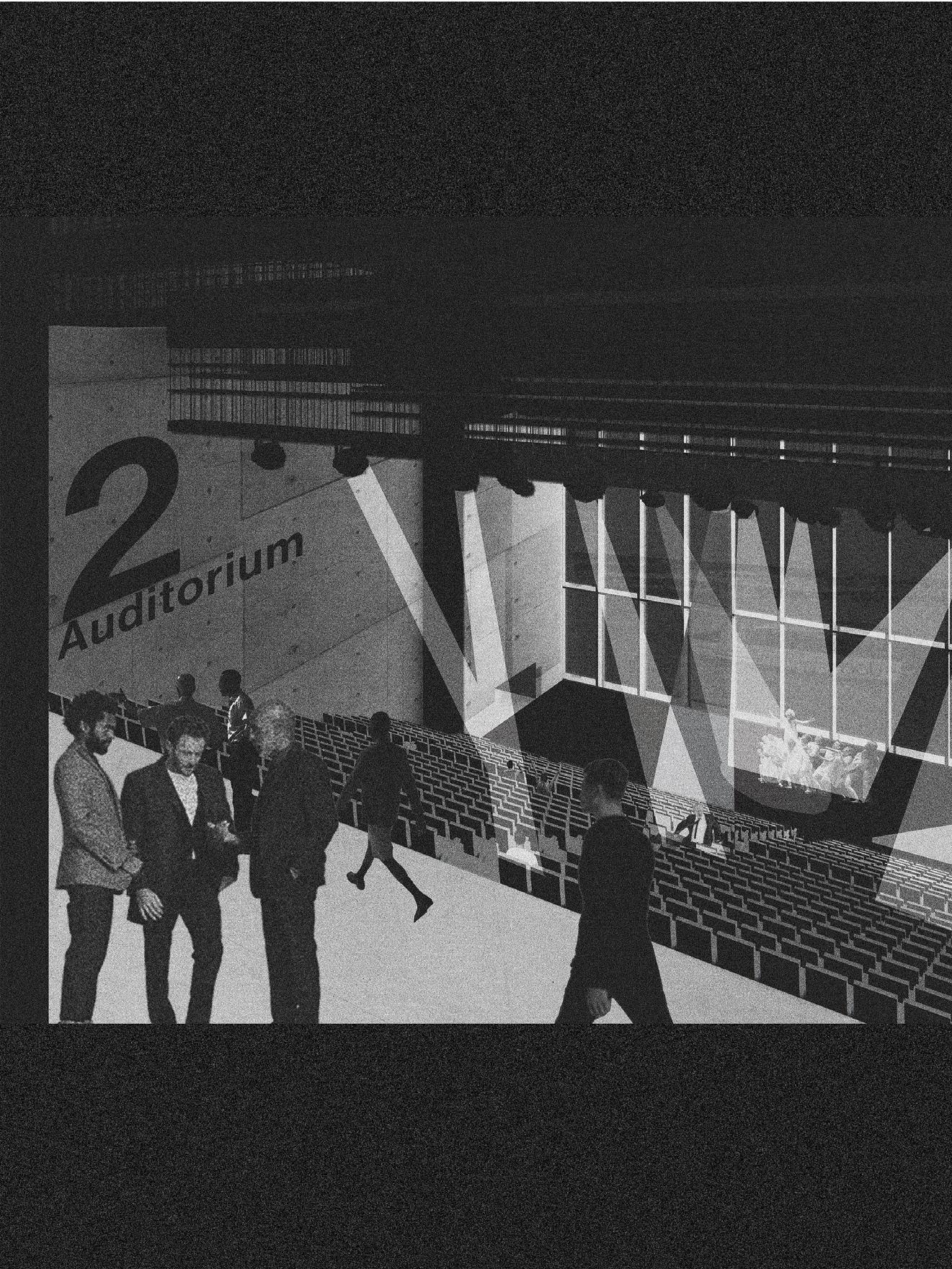

Each democratic component occupies one floor, with priority given to the lobby area. As this is a space used post-debate, its role is to create a condition where lobbying can be done as part of the wider dramaturgical ambition. Conceptually, it tries to overturn the lobby ritual found in the Palace of Westminster, which, as discussed previously, is highly exclusive. Here, the public forms the drive, rather than the other way round. Further, the research floor is filled with meeting spaces, where politicians/political bodies meet with actors to put together plays that would then be objectively enacted in front of the audience. Politics can only operate here if the public participates in it. In this sense, the entire suspended built landscape is utterly reliant on an active public, as, without its spectators, the programmes would virtually not exist. Lastly, the showcase takes the form of an open-plan gallery. Here, the scope is to exhibit new laws and regulations generated by the [re]Public’s democratic process - banners, posters, sculptures, or paintings.

The walls not only conceptually sustain the programmatic matrix, but they physically do so. Following the logic of a homogeneous building entity, the [re]public creates a comprehensive language throughout. The exploration focuses on how to re-envision a political theatre programme, maintaining sight of the programmatic needs. In doing so, the programme dictates the building form.

The debate takes the form of five auditoria nested between the programmatic walls. The studies of The Palace of Westminster and the Greek polis delineated two different logics: one which conceals, the other which reveals the decisionmaking mechanism. The [re]public thus, takes an inclusive stance and chooses to reveal the political conditions it fosters. Formally expressed

as porous entities, the auditoria act equally as a forum and as a theatre space. The ritualistic processes found in Westminster turn here into procedural rituals, wherein one uses the building following a programmatic logic, centred around the debate. Reversing the commodification of theatre today, the [re]Public starts to become a modus operandi for an agonistic democracy.

Using concrete as the main material further highlights the solidity and monumentality of the walls. There are five auditoria, one of which opens towards the newly landscaped park. Spanning from the left side of the site (Gabriel’s Wharf) towards the right extreme (OXO Towers), the furthest left two faces the park, and the furthest right ones face the water. In contrast to the sculptural character of the walls, the auditoria are encased in translucent glass – opaque during the day and bright at night. This develops the notion of transparency within politics, taking theatre from the dark rooms of commercial play into the public realm.

Fig. 33 (above) Detail A: Beam Wall to Floor Slab Connection 1:5 @ A4

Fig. 33 Exploded Structural Axonometrics - showing the theatre volume suspended off circular cores, above the bureaucratic bar

Fig. 34 Theatre Auditorium 2: Debate about to commence.

Fig. 34 Theatre Auditorium 2: Debate about to commence.

Fig. 35 Library and Lobby.

Fig. 35 Library and Lobby.

The constructed situation would performance, one that would treat space and all people as performers. situationism postured as the twentieth-century experimental which had been dedicated to and audience, of performance of theatrical experience and

would clearly be some sort of treat all space as performance performers. In this respect, the ultimate development of experimental theatre, the energies of to the integration of players performance space and spectator space, and “real” experience.

Simon Sadler on Guy Debord’s Situationism International, p105

This thesis started by making the case that theatre played, in fact, a vital role in Athenian democracy and beyond. Transporting the study into today’s oligarchic democracy of London, the evident dissolution of theatre is highly apparent. The Palace of Westminster uses theatrical rituals to stage elitist politics, while The National Theatre is a capitalist commodification. To study modes of reversing this, the paper focuses on Chantal Mouffe’s agonistic ideology. In discussing how an alternate post-political society might emerge, she argues that the construction of a landscape of productive conflict is vital.

In dissecting democracy as a spatial organism, four main categories emerge knowledge, research, debate, lobbying and showcasing. The Bernie Spain Garden became the chosen exploratory site where knowledge, research, lobbying and showcasing become part of a programmatic series of walls. The [re]public eventually becomes a dramaturgical monument, which recognises the importance of the relationship between bureaucracy and theatrocracy.

Guy Debord, an essential figure of the Situationist International Group, discusses the elementary role of theatre and spectacle (understood as part of the theatre) play, in creating a participatory public. Much like the Greek polis spectacle, Guy Debord and the Situationists use theatre as means of creating what they define as situations. As art historian Gabriel Zacarias puts it, ‘the situation was understood as the merger between the construction of the environment and the actions that result from it during a period (2011, p. 177). Asking how architecture might play a part in staging these, this thesis saw the creation of the [re]Public – a public debate landscape.

The social condition theatre represents within the context of this thesis, can only be explored in detail if the very notion of the public takes place. In other words, perhaps the most authentic way of representing the project is to visualise the life (literally) within it. Architecture, as built fabric, has a very limited influence on any socio-political conditions it houses. However, dramaturgy and spectacle give rise to several conditions, which might start reclaiming the wider institutional relationship. By dislocating theatre from the bureaucratic closed-circuit of Westminster and de-commodifying the spectacle played in The

National Theatre, the exploratory project allows politics and play to become a homogeneous language once again. The [re]Public thus takes the form of a series of situation clusters, where democracy plays out in monumental spaces, and where participation is vital for the exploration to come into existence.

The amphitheatres of Ancient Greece were, after all, simple stone structures. What made these structures immortal was in fact, the theatre. This thesis is a statement that the most significant architecture has, is to provide the infrastructure in which politics can begin to form.

Ultimately, the [re]public aims to materialise what the philosopher Brian Elliot concludes in the work of The Situationists: ‘the chance of contesting the current hegemony of statecontrolled consensus politics by relocating radical democratic politics to its original place of action – the urban street’. (2009).

Fig. 36 The [re]public Park ViewAfter proclaiming the inherent social dangers of theatre, Rousseau finally admitted that in an ideal republic there is a need for spectacles, but of a different nature. These spectacles must involve the entire population in an active way, rather than expecting them to witness an illusion passively (Pelletier, 2006)

After proclaiming the inherent social dangers of theatre, Rousseau finally admitted that in an ideal republic there is a need for spectacles, but of a different nature. These spectacles must involve the entire population in an active way, rather than expecting them to witness an illusion passively

- Pelletier, 2006

As one approaches the [re]public from the new Bernie Spain Gardens, a spectacle unfolds: while actors perform, a chorus surrounds them. In Ancient Greece, the chorus was a chosen group of actors representing the polis’ collective during theatre plays, who would comment and give live opinions on the dramatic play. Here, the corus represents the [re]public’s collective. This is a rendition of how direct democracy operates within the [re]public: unencumbered, people actively participate in political plays.

boat with spectators

Fig. 37 The [re]public Thames view

boat with spectators

Fig. 37 The [re]public Thames view

A boat with spectators approaches the [re]public from the Thames. The bureaucracy bar sees the river’s high tides almost submerging it under water, while the auditoria sit silent awaiting for the next play to begin. A few people are enjoying the new promenade in the background.

Thames view approaches the [re]public from the Thames. The bureaucracy bar sees the river’s high tides almost submerging it under water, while silent awaiting for the next play to begin. A few people are enjoying the new promenade in the background.

Adorno, T.W. (2015). Culture industry : selected essays on mass culture. Routledge. Arendt, H. (1958). The Human Condition. Chicago ; London: University Of Chicago Press. Barthes, R. (1985). The responsibility of forms : critical essays on music, art, and representation. New York: Hill and Wang.

Bharne, V. (2011). Le Corbusier’s Ruin : The Changing Face of Chandigarh’s Capitol. Journal of Architectural Education, 64, pp.99–112.

Bishop, C. (2012). Artificial hells participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. London Verso.

Boesiger, W. (1995). Le Corbusier - Ouvre complète Volume 8: 1965-1969Les dernières oeuvres / The Last Works / Die letzten Werke. Berlin, München, Boston De Gruyter.

Bradlaugh, C. (1889). The Rules, Customs and Procedure of the House of Commons. Pp. Xii. 153. Swan Sonnenschein & Co.: London.

Britannica (1998). Alienation Effect. In: Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/art/alienation-effect [Accessed 4 Mar. 2022].

Cartledge, P. (2012). Ancient Greek political thought in practice. Cambridge, United Kingdom ; New York, New York: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom ; New York, New York.

Cartledge, P. (2018). Democracy : a life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Coin Street. (n.d.). Bernie Spain Gardens. [online] Available at: https://coinstreet.org/index.php/space-and-venue-hire/bernie-spain-gardens [Accessed 11 Apr. 2022].

Corbusier, L. (1931). Towards A New Architecture. New York: Brewer, Warren & Putnam. Diamond, L. (2004). What is Democracy?.

Dickenson, C.P. (2017). On the agora : the evolution of a public space in Hellenistic andRoman Greece (c. 323 BC - 267 AD). Leiden: Brill.

Diderot, D. and Goldzink, J. (2005). Le fils naturel, Le père de famille, Est-il bon? Est-il méchant. Paris: Flammarion.

Dragan Klaić (2012). Resetting the stage : public theatre between the market and democracy. Bristol: Intellect, pp.138–139.

Eckersall, P. and Grehan, H. (2019). The Routledge companion to theatre and politics. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, Ny: Routledge.

Elliott, B. (2009). Debord, Constant, and the Politics of Situationist.

Ferrone, A. (2021). Stage business and the neoliberal theatre of London. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gottesman, A. (2017). Politics and the street in democratic Athens. Cambridge Cambridge University Press.

Hansen, M.H. (2001). The Athenian democracy in the age of Demosthenes : structure, principles, and ideology. London: Bristol Classical Press.

Harvey, D. (1975). Social justice and the city. Baltimore, Ml.: Johns Hopkins Univ. Pr.

House of Commons Information Office (2010). Factsheet G7 General Series House ofCommons Information Office Some Traditions and Customs of the House Contents. [online] UK Parliament. Available at: https://www.parliament.uk/about/how/guides/factsheets/general/g07/ [Accessed 1 Dec. 2021].

Jean-Pierre Vernant and Vidal-Naquet, P. (2006). Myth and tragedy in ancient Greece. New

Jeffrey Edward Green (2010). The eyes of the people : democracy in an age of spectatorship.

Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Malzacher, F. (2015). Not just a mirror : looking for the political theatre of today. Berlin: Alexander Verlag, Cop.

McKinnie, M. (2021). Theatre in market economies. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mcleish, K. and Griffiths, T.R. (2003). A guide to Greek theatre and drama. London: Methuen.

Meineck, P. (2018). Theatrocracy : Greek drama, cognition, and the imperative for theatre. Routledge.

Mogens Herman Hansen (2006). Polis : an introduction to the ancient Greek city-state. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Mouffe, C. (2000). The democratic paradox. London: Verso.

Mouffe, C. (2005). The Return Of The Political. S.L.: Verso Books.

Mouffe, C. (2013). Agonistics : thinking the world politically. London: Verso.

Pelletier, L. (2006). Architecture in words theatre, language and the sensuous space of architecture. London Taylor Francis.

Rousseau, J.-J. (1967). Lettre à Monsieur d’Alembert sur les spectacles. Flammarion.

Sadler, S. (2001). The situationist city. Cambridge (Mass.) ; London: The Mit Press.

Scheibe, K.E. (2002). The drama of everyday life. Cambridge, Mass. ; London: Harvard University Press.

Spencer, D. (2016). The architecture of neoliberalism : how contemporary architecture became an instrument of control and compliance. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.Stewart, P. (2020). Black Rod and the Door of the House of Commons. [online] Reformation to Referendum: Writing a New History of Parliament. Available at: https:// historyofparliamentblog.wordpress.com/2020/01/21/black-rod-and-the-door-of-the-house-ofcommons/.

Wiles, D. (2000). Greek theatre performance : an introduction. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wilson, P. (2007). The Greek theatre and festivals : documentary studies. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.Winkler, J.J. and Zeitlin, F.I. (1990). Nothing to do with Dionysos? : Athenian drama in its social context. Princeton, N.J. ; Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Wright, T. and Rush, M. (2003). Reform of the House of Commons. Source: RSA Journal,[online] 150(5509), pp.46–49. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41379429 [Accessed1 Mar. 2022].

Young, I.M. (2011). Responsibility for justice. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Boissoneault, L. (2017). Before the Fall of the Roman Republic, Income Inequality and XenophobiaThreatened Its Foundations. [online]

Smithsonian. Available at: inequality-and-xenophobia-threatened-its-foundations-180967249/.https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/fall-roman-republic-incomeColumbia University. (n.d.). Rousseau and Republicanism. [online] Available at: https://sofheyman.org/events/rousseau-and-republicanism-a-day-long-conference [Accessed 17 Apr. 2022].

UK Parliament (n.d.). The stonework. [online] Available at: https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/building/palace/architecture/palacestructure/the-stonework.

www.medicalnewstoday.com. (2019). Cognitive dissonance: Definition, effects, and examples.[online] Available at: medicalnewstoday.com/articles/326738#effectshttps://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/326738#effectshttps://www. [Accessed 30 Apr. 2022].

www.merriam-webster.com. (n.d.). Definition of CURTAIN-RAISER. [online] Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/curtain-raiser [Accessed 2 May 2022].

www.merriam-webster.com. (n.d.). Definition of POLIS. [online] Available at: https://www.merriamwebster.com/dictionary/polis.

Fig 00 Adapted from https://love.lambeth.gov.uk/bernie-spain-gardens-design-competitionopen-view/

Fig 02 Adapted from Boissoneault, L. (2017). Before the Fall of the Roman Republic, IncomeInequality and Xenophobia Threatened Its Foundations. [online] Smithsonian. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/fall-roman-republic-income-inequality-andxenophobia-threatened-its-foundations-180967249/ Credit: Paul Fearn/Alamy.

Fig 03 Adapted from Columbia University. (n.d.). Rousseau and Republicanism. [online] Available at: https://sofheyman.org/events/rousseau-and-republicanism-a-day-long-conference [Accessed 17 Apr. 2022].

Fig 04 Adapted from Fine Art America. (n.d.). The Theatre Of Dionysus, Athens, Greece byVintage Design Pics. [online] Available at: of-dionysus-athens-greece-ken-welsh.htmlhttps://fineartamerica.com/featured/the-theatre[Accessed 2 May 2022]. The Theatre Of Dionysus, Athens, Greece As It Would Have Appeared In Ancient Times. From The Book Harmsworth History Of The World Published 1908.

Fig 05Adapted from Stewart, H. (2019). Life in the lobby: ‘Debate in parliament can beintense, emotional theatre’. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian. com/membership/2019/jan/05/life-in-the-lobby-political-editor-heather-stewart MPs urge the speaker, John Bercow, right, to watch video footage of the Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn, supposedly muttering a sexist remark during prime minister’s questions. Photograph: HO/AFP/Getty Images.

Fig 06 A London Inheritance. (2021). The National Theatre - Denys Lasdun’s theatre on theSouthbank. [online] Available at: https://alondoninheritance.com/london-buildings/national-theatre/ [Accessed 1 May 2022].

Fig 07 Adapted from Britannica (2020). Bust of Aristotle. [Online Article] Britannica.Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/form-philosophy [Accessed 1 Dec. 2021].

Fig 08 Stephan, A. (2010). Ancient Greek Theaters, Seen from the Sky. [online] Getty Iris. Available at: https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/ancient-greek-theaters-seen-from-the-sky/[Accessed 1 May 2022].

Fg 09 Adapted from Sarkar, S. (2015). Role of CHORUS in Tragedy ~ All About EnglishLiterature. [online] Eng-literature.com. Available at: https://www.eng-literature.com/2015/10/ role-of-chorus-in-tragedy.html.

Fig 11 Adapted from Metmuseum.org. (2021). [online] Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/251532 Title: Terracotta calyx-krater (mixing bowl); Attributed to the Dolon Painter; Period: Late Classical; Date: ca. 400–390 B.C.; Culture: Greek, South Italian, Lucanian; Medium: Terracotta; red-figure; Dimensions: H. 12 1/16 in.(30.6 cm); diameter 12 1/2 in. (31.8 cm); Classification: Vases

Fig 13 Adapted from agefotostock. (n.d.). Critias ordering the execution of Theramenes,404 BC. [online] Available at: https://www.agefotostock.com/age/en/details-photo/critiasordering-the-execution-of-theramenes-404-bc-after-the-fall-of-athens-to-the-spartans-critiasas-one-of-the-thirty-tyrants/XY2-2982526 [Accessed 2 May 2022]. From Hutchinson’s History of the Nations, published 1915.

Fig 14 Thompson, H.A. and Wycherley, R.E. (1972). The Agora of Athens : the history, shape, and uses of an ancient city center. Princeton, N.J.: American School Of Classical Studies At Athens, p.58.

Fig 15 Adapted from Lawrence, S. (2016). What Does Black Rod Do The Rest Of The Year?[online] Londonist. Available at: https://londonist.com/2016/01/what-does-black-rod-do-the-rest-of-the-year [Accessed 2 May 2022].

Fig 16 Ibid. news.bbc.co.uk. (n.d.). BBC News | In Pictures. [online] Available at: http://news. bbc.co.uk/1/shared/spl/hi/pop_ups/03/uk_politics_state_opening_of_parliament/html/6.stm [Accessed 2 May 2022].

Fig 17 Adapted from The UK Parliament (2020). House of Commons: Looking back on 2020. UK Parliament.

Fig 18 ArchDaily. (2016). AD Classics: Palace of Westminster / Charles Barry & AugustusPugin. [online] Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/789671/ad-classics-palace-ofwestminster-houses-of-parliament-london-uk-charles-barry-and-augustus-pugin.

Fig 20 Adapted from visitlondon.com. (n.d.). Houses of Parliament. [online] Available at: https://www.visitlondon.com/things-to-do/place/401836-houses-of-parliament.

Fig 21 Adapted from Emden, C (n.d)

Fig 22 Adapted from Ghinitoiu, L. (n.d.). Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh.

Fig 23 Adapted from Corbusier, L. and Boesiger, W. (1985). Oeuvre complète 1952-1957 : Le Corbusier et son atelier rue de Sèvres 35. Zurich: Editions D’architecture.

Fig 25 Adapted from Jackson, I. (n.d.). Figure 2. Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh plan from 1951.Note the sector... [online] ResearchGate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/ Le-Corbusiers-Chandigarh-plan-from-1951-Note-the-sector-interiors-have-not-yet-been_ fig1_263271174 [Accessed 1 May 2022].

Fig 26 Adapted from southbanklondon.com. (n.d.). Things To Do In London | OXO TowerWharf | South Bank. [online] Available at: https://southbanklondon.com/attractions/oxo-tower-wharf [Accessed 2 May 2022].

Fig 27 Generated by Google Earth.

All images not referenced here are author’s work.

Laura Moldovan Year 5 Glamour Unit University of Dundee 2021/22