David Antonio Cruz come

close, like before

Front cover: icouldn’tcallitbynamebefore,butmaybeit’sbeentheresinceifirstknewyou., 2024 (detail)

Back cover: iknowyou’vebeenwonderingwherei’vbeen:adrift,adraft,astare,ati lt,asigh,exhale.but,icamebacktoletyouknow,gotathingforyou,andican’tletitgo_ theraft., 2024 (detail)

David Antonio Cruz come close, like before

Monique Meloche Gallery

September 13 - October 26, 2024

Essays by Timothy E. Bradley and Marcos Gonsalez

Edited by Staci Boris

Photographed by Bob.

This catalogue was published on the occasion of come close, like before, a solo exhibtion at Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago

Designed by Julia Marks ©2024

Introduction by Alyssa Brubaker

moniquemeloche is pleased to present David Antonio Cruz: come close, like before, the artist’s third solo exhibition with the gallery.

come close, like before is a continuation of Cruz’s “chosenfamily” series–exploring the non-biological bonds between queer people that are based in mutual love and support–and centers this structure within the historical canon of western art, specifically maritime and landscape painting. Cruz produced this body of work after extensive travel during the last year and a half, having undergone an artist residency in Laguarres, Spain and visiting his grandparent’s land in Humacao, Puerto Rico. Reflecting on themes of lineage, family, and home, as well as the complex history between Spain and Puerto Rico, Cruz contemplates ideas of drift and voyage rendered through a distinctly queer, Brown perspective.

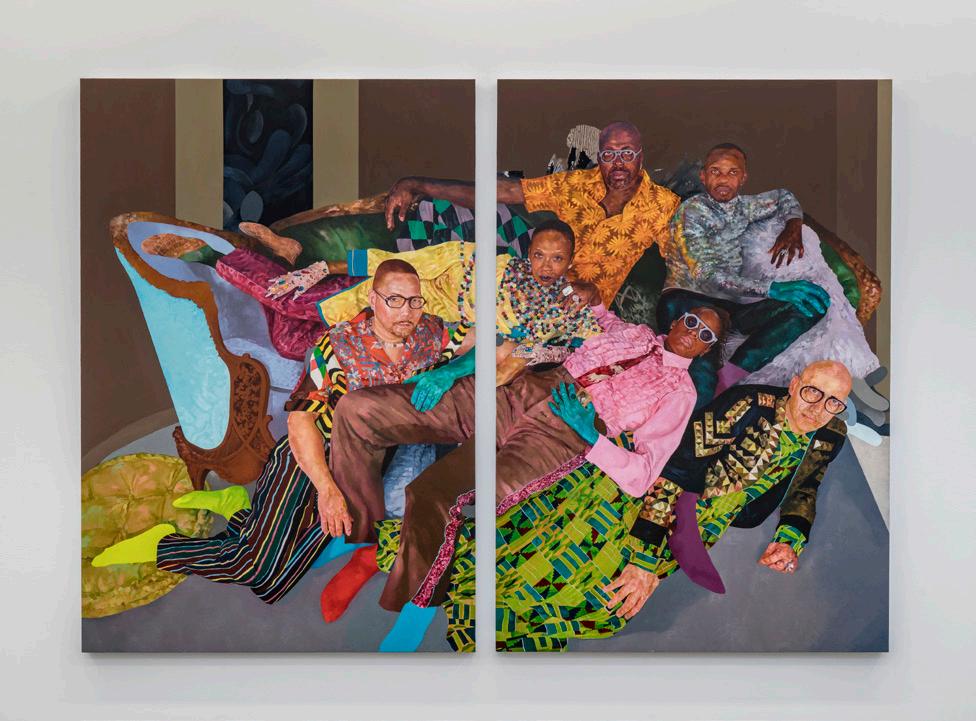

The colonial and Eurocentric roots of maritime painting evolved alongside European colonization of the Americas, Africa, and various other regions worldwide, made possible through seafaring. A particular work resonated with the artist during his travels, Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault. Monumental in stature and considered to be the most famous painting of a shipwreck, it narrates the tale of the French frigate Medusa’s shipwreck and the plight of the survivors adrift on a makeshift wooden raft. America’s deep relationship with its waterways involve complex histories, with the sea representing a feeling of connection, vast expansiveness, beauty, and violence. For Black and Latinx Americans, the history of home making is inextricably linked with conflict. In the painting titled, iknowyou’vebeenwonderingwherei’vebeen:adrift,adraft,astare,atill,asigh,exhale.but,icamebacktoletyouknow,gotathingforyou,andican’letitgo_theraft., Cruz’s subjects billow atop fragmented furniture within a liminal space, their forms enacting a similar composition to Medusa, à la lost at sea. But rather than a hopeless depiction, the figures are resolute in their commitment to and safe keeping of each other. iknowyou’vebeenwondering… is a celebration of how our bodies represent home, and there is room for everyone on this raft.

In Cruz’s works on paper, bodies are fragmented, drifting in and out of the foliage, floating in air. Birds delicately rendered suggest migration and movement, while the limbs of spiked Ceiba trees hold us tight to the land, a lightness and heaviness at the same time. This motif found in Cruz’s drawings permeate into his paintings. Whether as a backdrop, garment, or textile, this lush vegetation centers around a geographic location personal to the artist or subjects depicted (Laguarres, Philadelphia, Brooklyn), and is a way of tracing things back to their roots. In his painting icamebackthefollowingnightandwalkedthegroundslookingforyou,wegotturnedawayonthesecondnight,buticamebackagainandagain,andagain, figures pile together suggestive of a mountain, the collective mound of identities and histories coalesce into a single unified body. Prolonged viewing gives way to the layers beneath, where we realize the figures are simultaneously bound together and disjointed, a necessary tension created to shift modes of thinking.

Topographical influences aside, one cannot ignore the spectrum of texture, pattern, color, and design that Cruz’s subjects employ. Before paint meets panel, elaborate photoshoots ensued in the artist’s Bronx studio and Los Angeles. Chosen family members play dress up, combining sequins, lace, and pearls with high fashion garments. Cruz purposefully choreographs the composition, gaining the trust of his sitters along the away. Poses inspired by 1990s fashion photography encapsulate a sexy freedom or dirty realism, highlighting a visual language that helped shape the perspective of a generation. Subtle coding references 60s, 70s and 80s gay culture and bits of flat color and glitchy moments when the compositions break channel a resistance to the status quo.

As the title suggests, come close, like before asks us to reflect how and who we consider home. It’s a return to our roots after drifting away, it’s knowing that everything you need you already carry with you.

Introduction

A Most Luxuriant Slackness

by Marcos Gonsalez

Neither’s grasp is tight. Gently emplaced, a lightness of body, the slight feeling of presence—hands on the other barely registering as touch. The artist tells me in his studio icouldn’tcallitbynamebefore,butmaybeit’sbeentheresinceifirstknewyou. is a painting of the scholar Arnaldo Cruz-Malavé and his partner. The work does not reveal the face of the Puerto Rican theorist, just the back of his head, but we do get to see the face of the scholar’s beloved: a face emanating softness, an even softer smile, soft eyes, as if star-gazing, as if daydreaming, as if the scholar’s delicate enfolding there produces wonderment itself in the muscles of the face. A slackness engulfs the lovers. The pair’s embrace loose, yet intimate, and at ease. In a world astoundingly cruel to queer folks, particularly queers of color, I want to believe that this is what queer love is, in the grand scheme of things, a safe softness that lets us look into the unknown with awe, fear-gone, where a sense of belonging, of home, feels like a loose-closeness, “an extravagantly joyous decolonial hope, that the body knows but that cannot be put into words,” as Cruz-Malavé might put it.1

Throughout David Antonio Cruz’s work slackness radiates from both subjects and objects, a general aesthetic aura: hands dangling limply off the side of a couch; fabric undulating off bodies; necks leaning upon a torso totally relaxed. Cliché, certainly, but the Oxford English Dictionary provides tantalizing definitional direction for the possibilities of that most curious word, “slack”: “To make slack or loose; to render less tense or taut; to loosen, relax.” In the instance of a noun: “That part of a rope, sail, etc., which is not fully strained, or which hangs loose; a loose part or end.” Thinking of that phrase, “Cut me some slack,” in that the person making the request for slack to be given is asking for a less harsh treatment, to ease the judgment upon them. The article of clothing, slacks, which are loosely cut pants, also come to mind. Slackness, then: loose, the lessening of tautness or tenseness, relaxing, not straining, hanging free. I like to think a queer politic can emerge from the sense of slackness Cruz’s work evokes.

1 Arnaldo Cruz-Malavé, “Dancing in an Enclosure: Activism and Mourning in the Puerto Rican Summer of 2019” Small Axe 26, no. 2 (2022): 23.

comebackandseemeonceagain;givemesometimetoremindyouwhatit'slike,rightbytheplaceweusedtogo., 2024 (detail)

The slack worlds Cruz’s paintings depict imagine an untautening of the incredibly stiff, and stifling, logics of capitalist modernity and colonial violence. Bodies not laboring, bodies unwinding, bodies resting, bodies comfortably together on couches. Queers gathering, slackly laying and holding and leaning on one another, at ease assemblages of lives cozily entangled.

Queer bodies all over each other gently, lightly, loosely. Time feels slow, pleasurably slowed, in Cruz’s imaginings, maybe somehow even against time itself because the subjects seem to be luxuriating in the non-time, in their own queer eternity, that they are spending together there on the canvas. Though comfily lounging on another, Cruz’s muses are not still, because stillness suggests the static, stagnation, the inactive.

The slack bodies throughout droop, drape, and dangle, ever so vitally, alive. What the viewer experiences are relaxed intimacies, love between and amongst queers that highlights mutual tenderness, defenses down and tensions away, the trials and tribulations of the quotidian somewhere else. These are most queer space-times the viewer gets to luxuriate in. A politics of queerness that is about the lessening of pain, the lessening of trauma, the lessening of the structural antagonisms one must live daily through the loosening up of relationality, a slackening into one another.

comebackandseemeonceagain;givemesometimetoremindyouwhatit'slike,rightbytheplaceweusedtogo., 2024 (detail)

Arnaldo Cruz-Malavé, “Dancing in an Enclosure: Activism and Mourning in the Puerto Rican Summer of 2019” Small Axe 26, no. 2 (2022): 23. José Esteban Muñoz, “The Sense of Watching Tony Sleep,” in After Sex? On Writing Since Queer Theory (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 142.

Arnaldo Cruz-Malavé, Queer Latino Testimonio, Keith Haring, and Juanito Xtravaganza: Hard Tails (New York: Routledge, 2007), 95.

In comebackandseemeonceagain;givemesometimetoremindyouwhatit’slike,rightbytheplaceweusedtogo., the couple portrayed is not slackly holding but rather slackly lounging on one another—an arm over a leg, a foot over a couch or shoulder, an elbow hanging in space. Their positioning on the couch is odd, as if they are scissoring in reverse. A record box on the floor with the inscription “Patería” draws the eye down for a brief moment—a Barthesian punctum, a Caribbean hailing—but then immediately back up to the lounging pair. They look straight ahead at us, gaze severe, undercutting the whimsicality of their entanglement. Two extremes of meaning, two in love—how very queer. The two look like they could, at any moment, just float away.

“Often, after sex, there is sleep,” writes the late queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz in a brief essay he wrote on the artist, Tony Just. “And while I am not interested in displacing the relational and affective centrality of sex it also seems important to dwell upon modes of being in the world that might be less knowable than sex.”2 Queer theory, since its inception, has theorized extensively on sex, as Muñoz well enough suggests, and popular discourse around queer life frequently revolves around discussing, and debating, sex, as anyone who scrolls through social media can attest. The queerness, then, that Cruz offers us in his work are part of Muñoz’s “modes of being” that are less known, and what Cruz-Malavé aptly postulated elsewhere as a “lesson in listening for elusive meanings and emerging significations.”3

Queers luxuriantly lounging on top of another, queers untightly holding a beloved, queers slacking on fancy couches. A different sense of the world occurs in Cruz’s imaginings made real on the gallery wall. Maybe it’s not exactly this world or a reflection of our reality, but somewhere else—someplace where we are relaxed in our belonging and lazing intimacies that allow us to be at home with one another comfortably.

icouldn’tcallitbynamebefore,butmaybeit’sbeentheresinceifirstknewyou., 2024(detail)

2 José Esteban Muñoz, “The Sense of Watching Tony Sleep,” in After Sex? On Writing Since Queer Theory (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 142.

3 Arnaldo Cruz-Malavé, Queer Latino Testimonio, Keith Haring, and Juanito Xtravaganza: Hard Tails (New York: Routledge, 2007), 95.

Installation Views

I’ll

see you when the sun sets

I’ll see you when the sun sets

by Timothy E. Bradley

Do you wanna hear the song?

We listen to music after leaving the studio.

For him it’s a way to decompress after standing twelve or more hours before the wood panels—hoisting them onto the table for a better angle, combining four kinds of blue to create a fifth, painting pearls, painting sequins and socks and filling troublesome gaps, brushing a friend’s cheekbones into being. Studying all their faces.

Sometimes he wipes a whole section down and starts over. Or, after an immersive flurry, he steps back exclaiming, I don’t know how I did that. Often, he sits silently in an armchair facing the panel, looking. comeclose,likebefore,sowecansitinsilenceandcloseoureyestothosewants,andmaybe,maybe,wecangetlostintheplacewherethebirdssleep,lostinthesummerheat., 2024

When we climb into the car near midnight, he says: My whole body hurts. I feel it in my whole body.

On the drive home from The Bronx through Harlem we listen to Rosalía, Erykah Badu, Meshell Ndegeocello, volume up and windows down if it isn’t raining. We look out for stray pedestrians, watch for the bars on Malcolm X where crowds spill out onto the sidewalk, getting our taste of summer in the city.

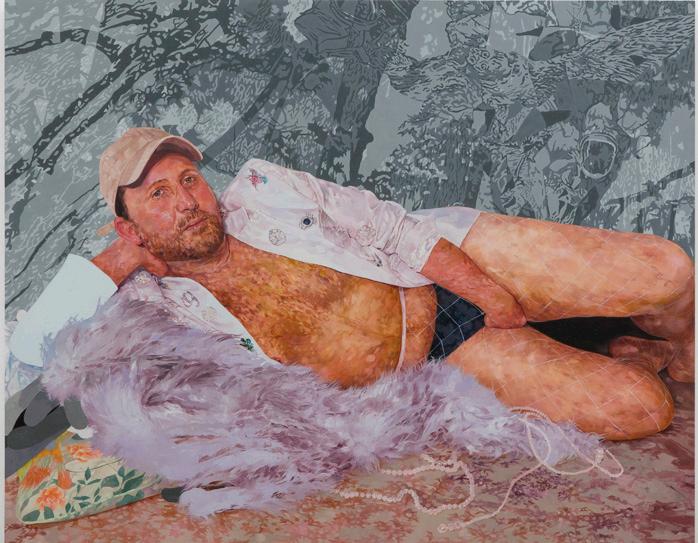

The song he offers to play that night is the inspiration for the title of the painting he was just working on, the suggestive one of the shirtless man lounging on the plush violet throw. I understand his sharing to mean: do you want to hear what’s going on inside me?

For the first twenty seconds, “Sunsets – Pt. 2” sounds like a disco track gathering form, shimmering with arpeggiation and a fleeting, pixilated feel. Then a warm pulsing synth swells until all at once the bass drops and a voice calls out: Come close like before / do you remember how it feels / to know what you’re living for?

I hear a plea across time. A yearning, not to be confused with heartbreak, not the not-having of festering want or rejection; the singer’s voice is too commanding, too sure of where it’s been.

The new works, imbued with this song and others, respond to a turbulent, unraveling, unpredictable time by presenting a series of collectives, couples, and solo acts who seem to know what they’re living for.

comeclose,likebefore,sowecansitinsilenceandcloseoureyestothosewants,andmaybe,maybe,wecangetlostintheplacewherethebirdssleep,lostinthesummerheat., 2024 (detail)

I’ll see you when the sun sets

Whether taking flight or linking arms so closely there’s no space between them, the subjects in these paintings and drawings have a way of showing force and strength without losing their cool. They exude power, grace, and ease.

In the title work, comecloselikebefore, the bare-chested figure greets the viewer in full queer regalia. Subverting Burt Reynolds’ iconic 1972 Cosmopolitan centerfold, he trades the macho cigarillo and fanged bearskin rug for a look that blurs the femme and masc, mixing a baseball cap and sportscoat glittering with pastel brooches alongside velvet underwear and fishnet stockings. He appears to have just slipped on the outfit—or maybe never took if off last night? His skin glows with a trace of sweat and stimulation.

The sitter may have just rolled out of bed, onto a Persian rug strewn with pearls, but the floor’s intricate patterning mirrors an elaborate cascading event behind him. That cosmological Rorschach moment is coded with tree branches tied to the artist’s ancestral roots; futurist space helmets suggesting the gear of post-apocalyptic survivors; and the haunting owls of Francisco Goya’s Los Caprichos series, evoking a time of unrest. Are these his dreams, his subconscious? He’s a universe, a monument, unto himself.

Even the jacket tells a story. For the 2023 performances of his operatic work, green,howiwantyougreen, the artist designed the jacket to be worn by the rakish but sensitive young man who makes his first discoveries of love. In the opera, the character tenderly reminisces how “it was new, so new,” how “dawn brought us together on the bed.” Later, however, he goes on to suffer heartbreak and disillusion, lamenting: “I know you don’t love me... Don’t say you do.”

In comecloselikebefore, the wearer of the jacket suggests an evolved avatar. He has become both centerfold stud and the odalisque in waiting. He has moved past the heartaches of youth, abandoned any deference to how a boy is meant to be, and the triangular black hole into which his hand disappears leaves room to wonder what he’s keeping to himself. He is balanced between remembrance and invitation, past and potentiality, drifting.

I’ll see you when the sun sets

comeclose,likebefore,sowecansitinsilenceandcloseoureyestothosewants,andmaybe,maybe,wecangetlostintheplacewherethebirdssleep,lostinthesummerheat., 2024 (detail)

Your titles are always about return, I observe.

Not in a bad way, he says.

Don’t you remember how hard I loved you, baby?

It’s commemoration.

In queer life, to make contact with a trusting soul is a miracle. The loves we let in, who let us in, leave lasting imprints. Even when it’s over, the bonds remain and remain capable of being summoned. Surely, one of the best antidotes to grief is knowing that one has loved.

Artworks

thefogwillrise,theclaydry,andallcoveredindew.buti’llseeyouwhenthesunsets_causewehavelivingghosts., 2024 ink, flashe, and wax pencil on watercolor paper

77 1/4 x 56 5/8 in 196.2 x 143.8 cm

comebackandseemeonceagain;givemesometimetoremindyouwhatit’slike,rightbytheplaceweusedtogo., 2024

oil and acrylic on wood panel

48 x 72 in 121.9 x 182.9 cm

iknowyou’vebeenwonderingwherei’vebeen:adrift,adraft,astare,atilt,asigh,exhale.but,icamebacktoletyouknow,gotathingforyou,andican’tletitgo_theraft., 2024 oil, acrylic, and ink on wood panel

72 x 98 1/2 x 2 in (total)

182.9 x 250.2 x 5.1 cm

you’renotbymyside_won’tyouremember?, 2024 ink, flashe, and wax pencil on watercolor paper

77 1/4 x 56 5/8 in 196.2 x 143.8 cm

icamebackthefollowingnightandwalkedthegroundslookingforyou,wegotturnedawayonthesecondnight,buticamebackagainandagain,andagain_themound., 2024 oil and acrylic on wood panel

72 x 98 1/2 x 2 in (total)

182.9 x 250.2 x 5.1 cm

comeclose,likebefore,sowecansitinsilenceandcloseoureyestothosewants, andmaybe,maybe,wecangetlostintheplacewherethebirdssleep,lostinthesummerheat., 2024

oil and acrylic on wood panel

48 x 60 x 2 in 152.4 x 121.9 x 5.1 cm

andwe’lltakeapauseonthecoast,andthejujuwilldevourus., 2024 ink, flashe, and wax pencil on watercolor paper

77 1/4 x 56 5/8 in 196.2 x 143.8 cm

icouldn’tcallitbynamebefore,butmaybeit’sbeentheresinceifirstknewyou., 2024 oil and latex on wood panel

36 x 36 x 2 in 91.4 x 91.4 x 5.1 cm

I’ll see you when the sun sets

David Antonio Cruz explores the intersectionality of queerness and race through painting, sculpture, and performance. Focusing on queer, trans, and gender-fluid communities of color, Cruz examines the violence perpetrated against their members, conveying his subjects both as specific individuals and as monumental signifiers for large and urgent systemic concerns. A recent series explores the notion of “chosen family,” the nonbiological bonds between queer people based on mutual support and love. Each painting depicts the likeness of the artist’s community, and at the same time, the portraits strive to capture much more than the physical representation of the figures; they venerate the overall structure of queer relationships, captured through intimate moments of touch, strength, support, and celebration.

I’ll see you when the sun sets

Cruz (b. 1974, Philadelphia, PA) received his BFA in Painting from Pratt Institute, NY, and his MFA from Yale University, CT. He attended Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and completed the AIM Program at the Bronx Museum, New York. Recent solo exhibitions include When the Children Come Home, Sugar Hill Children’s Museum of Art and Storytelling, New York, NY (2024) and Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, PA (2023); so you are back again, you are here, and we are here with you, Galleria Poggiali, Florence, IT (2023); and moniquemeloche, Chicago, IL (2024, 2021, 2019). Group exhibitions include the Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita, KS (2024); Zuckerman Museum of Art, Kennesaw, GA (2023); DeCordova Sculpture Park and Museum for the New England Triennial, Lincoln, MA (2022); The Block Museum at Northwestern, Evanston, IL (2022); Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA (2022); Museum of African Diaspora, San Francisco, CA (2022); Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY (2019); Ford Foundation, New York, NY (2019); McNay Museum, San Antonio, TX (2019); and the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C. (2019). Forthcoming solo exhibitions include Halsey Institute of Fine Art, Charleston, SC (2025); and Wave Hill Museum, Bronx, NY (2025). Cruz is a 2025 Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition prizewinner.

His work is in the collections of the Newark Museum of Art, Newark, NJ; El Museo Del Barrio, New York, NY; Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA; 21c Museum Hotels, Louisville, KY; Pierce & Hill Harper Arts Foundation, Detroit, MI; Tufts University, Medford, MA; The Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, OK; and Green Family Art Foundation, Dallas, TX. Recent residencies and fellowships include Anderson Ranch Arts Center, Snowmass Village, CO (2024); Villa Bergerie Art Residency, Laguarres, Spain (2023); The Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Award (2018); Neubauer Faculty Fellowship, Tufts University, Boston (2018); BRIC Workspace Residency, Brooklyn (2018); Gateway Project Spaces, Newark, NJ (2016); and the LMCC Workspace Residency, New York (2015). Cruz lives and works in New York City, where he is the Assistant Professor of Visual Arts at Columbia University.

I’ll see you when the sun sets

Marcos Gonsalez is an author, essayist, scholar, and assistant professor of English living in New York City. His research on queer and trans Latinx aesthetics and cultural production has been supported by the Ford Foundation and Mellon Foundation. Gonsalez’s research and writing have appeared or are forthcoming in Literary Hub, Transgender Studies Quarterly, The White Review, BOMB Magazine, Inside Higher Education, Ploughshares, Post45, ASAP/Journal, Los Angeles Review of Books, Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society, The New Inquiry, and elsewhere.

I’ll see you when the sun sets

Timothy E. Bradley (he/him) is a New York City-based writer and educator whose work explores queer aging and memory, the climate crisis, artificial intelligence, and music and visual art. A 2024 Visual AIDS Research Fellow, his work has been published by Foglifter Journal and Galleria Poggiali. He has received residences and awards from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, Tin House Summer Workshop, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the Good Hart Artist Residency. Timothy is a graduate of Yale and the MFA program at Hunter College. He teaches at Queens College and John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Exhibition Checklist

comebackandseemeonceagain;givemesometimetoremindyouwhatit’slike,rightbytheplaceweusedtogo., 2024 oil and acrylic on wood panel

48 x 72 in 121.9 x 182.9 cm

iknowyou’vebeenwonderingwherei’vebeen:adrift,adraft,astare,atilt,asigh,exhale. but,icamebacktoletyouknow,gotathingforyou,andican’tletitgo_theraft., 2024 oil, acrylic, and ink on wood panel

72 x 98 1/2 x 2 in (total)

182.9 x 250.2 x 5.1 cm

thefogwillrise,theclaydry,andallcoveredindew.buti’llseeyouwhenthesunsets_causewehavelivingghosts., 2024 ink, flashe, and wax pencil on watercolor paper

77 1/4 x 56 5/8 in 196.2 x 143.8 cm

you’renotbymyside_won’tyouremember?, 2024 ink, flashe, and wax pencil on watercolor paper

77 1/4 x 56 5/8 in 196.2 x 143.8 cm

icamebackthefollowingnightandwalkedthegroundslookingforyou,wegotturnedawayonthesecondnight,buticamebackagainandagain,andagain_themound., 2024 oil and acrylic on wood panel

72 x 98 1/2 x 2 in (total)

182.9 x 250.2 x 5.1 cm

comeclose,likebefore,sowecansitinsilenceandcloseoureyestothosewants,andmaybe,maybe,wecangetlostintheplacewherethebirdssleep,lostinthesummerheat., 2024 oil and acrylic on wood panel

48 x 60 x 2 in

152.4 x 121.9 x 5.1 cm

andwe’lltakeapauseonthecoast,andthejujuwilldevourus., 2024 ink, flashe, and wax pencil on watercolor paper

77 1/4 x 56 5/8 in 196.2 x 143.8 cm

icouldn’tcallitbynamebefore,butmaybeit’sbeentheresinceifirstknewyou., 2024 oil and latex on wood panel

36 x 36 x 2 in

91.4 x 91.4 x 5.1 cm

Image Credits:

Unless otherwise noted, all images are by Bob.

Additional Image Credits: pgs.14-15; 90-91 Artist collages and personal photographs courtesy of David Antonio Cruz

Monique Meloche Gallery is located at 451 N Paulina Street, Chicago, IL 60622 For additional info, visit moniquemeloche.com or email info@moniquemeloche.com