6 minute read

The Helper

By Susan Barth

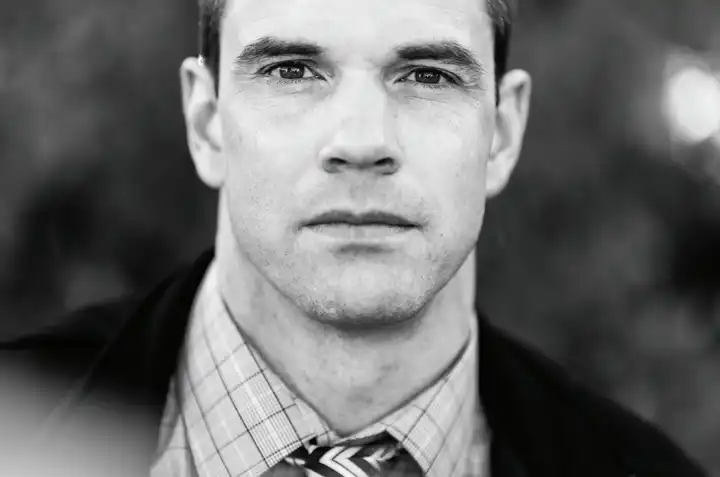

Cory Sonnemann makes you want to step up and volunteer—even though it’s quickly apparent that it would be difficult to do as much as he does. Cory (Chemistry ’10) is a psychiatrist who works at the Montana State prison and Southwest Community Health, a foster dad, and one of the most decent human beings you’ll ever meet. He’s also working hard to found a southwest Montana chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). He finds a way to help wherever he is, however he can.

Advertisement

Cory grew up in Billings, the only child of a pharmacist and a retail counselor. In high school he didn’t have any particular idea what he wanted to do, but he knew he wanted to play football in college. His choice was to walk on at MSU or U of M, or play at Montana Tech with a football scholarship…which sounded a lot better. He decided to major in Petroleum Engineering.

After a year he realized neither football nor Petroleum Engineering was for him. Fortunately he connected with a mentor, Dr. Marisa Pedulla, who gave him the opportunity to participate in research projects in microbiology, and encouraged him to present at national conferences. Cory credits Dr. Pedulla with putting him on the path to medical school.

The other major influence during Cory’s Tech career was Big Brothers Big Sisters. Cory volunteered as a Big Brother to a 12-year-old Butte boy named Dylan. “It’s a unique situation,” Cory said, “but he lived with me and my roommate for a while, while I was going to Tech. Then I ended up taking him to medical school with me. I was a single dad in medical school.”

That’s right: Cory not only took in his little brother, but when he moved to Yakima, Washington to start medical school at Pacific Northwest University, he took the boy with him (with his family’s permission). “I did my full 10 hour day or whatever it was while he went to high school,” Cory said. “Then after school, he’d come back to medical school and wait for me to be done. Then we’d go back to our one-bedroom basement apartment in Yakima. We did that for two years. He was a successful baseball player there. And then when we came back to Montana, he felt comfortable moving back with his mom. It was fun. He’s all grown up now, and doing good. And it shaped the way I wanted to do things, how I want to influence communities for the better.”

Cory had decided that he wanted to not just be a doctor, but a psychiatrist. And he wanted, someday, to bring those skills back to Butte, where they were—and are—badly needed.

After those two years in Yakima, Cory did the rest of his rotations in Montana, in Billings, Butte, and Miles City. He worked in mental health where possible, though he also did a stint of OB/GYN, delivering babies. Then it was decision time on where to go for residency. He interviewed at eight or nine places, including Michigan, Georgia, Ohio, and Elmira, New York. The last one wasn’t love at first sight. “I remember thinking as I got on the plane in Elmira, ‘I’m never going to come here,’” he said. “Then I got a call from the program director that I was really high on their list. So I thought, well, I’ll just deal with Elmira, New York. Now I love Elmira.”

Elmira is similar to Butte: people sometimes have a bad first impression, but grow to love the place. “Those are the two communities I love the most,” Cory said. “They’re the ones that struggle the most with socioeconomic factors and such. But there are plenty of opportunities to help. That’s probably why I enjoy them so much.” With a recommendation from Dr. Pedulla, Cory received a prestigious National Health Service Corps scholarship, which pays for the full cost of medical school, but requires one year of practice in an underserved community for each year of school paid for.

He went to Elmira as a resident, with one year in internal medicine and the rest in psychiatry. His favorite part there was ACT, or Assertive Community Treatment. “You just jump in a car and find people who need help,” he said. “You find them on the street, give them their medicine, and give them help directly. It was so cool.”

The doctors in New York were so impressed with Cory that they made him generous offers to stay there, including heading up clinical outpatient services at the University of Rochester. But Cory had made a commitment to himself to come back to Montana, where he felt he was most needed.

Right before he was going to leave, Cory made another critical connection: he took in two brothers, Alex and Jordan, who were in foster care. He really bonded with the boys, but he had signed a contract to come to Montana, so he had to leave them behind, still in foster care.

—Cory Sonnemann

“We did video visits every week for a year,” he said. “And then, eventually, social services said they weren’t going back with their family. They’ve been through a lot, and they didn’t have any good options for the boys. So they called me, and I flew out and picked them up.”

Cory brought the two brothers, now 10 and 11, to Montana, and is in the process of adopting them formally, again as a single parent.

Though he doesn’t exactly have a lot of spare time—after all, he has two very demanding jobs—they make it work. “We’re pretty happy,” he said. “We like hanging out together.”

Cory likes both of his positions in southwest Montana, but particularly enjoys his work at Montana State Prison. “At the prison, I’m getting the opportunity to help people who suffer from severe mental illness. Most of them haven’t been able to get help before coming to prison. Something like 40% of inmates there suffer from mental illness. I have time with the prisoners to talk about their problems and get them set up with services for when they leave so that they can be successful.” Cory is also the driver behind trying to bring a NAMI chapter, which focuses on peer support, to southwest Montana. “We already are working on getting our first event organized, a Family and Friends Information Support Group. There are people being trained as facilitators, but the ultimate goal is to have a group that’s open to anyone and everyone who has experienced mental illness. They can come together and just bounce things off each other. Mental health professionals can’t be there every time there is a crisis, so peer support can really help.”

When asked what would make a difference in mental health in Montana, Cory was quick to answer: “Destigmatizing mental health and making it okay to talk about it is the biggest thing. People don’t feel they can say anything when they’re not feeling well—it’s a mentality here. I think we can shift the culture, but it has to be done in a Montana way.”

If anyone can do it, Cory can—he’s a Determined Doer in the classic Montana Tech style. But the rest of us need to follow his example, and help each other as best we can.